Borges - A Case of Philosophy

Transcript of Borges - A Case of Philosophy

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 1/9

Mind Association

Philosophy as Literature: The Case of BorgesAuthor(s): J. AgassiSource: Mind, New Series, Vol. 79, No. 314 (Apr., 1970), pp. 287-294Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Mind Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2252659 .

Accessed: 14/10/2013 20:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press and Mind Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Mind.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 2/9

G. J. WARNOCK: Seeing and Knotwing 287

For you took it, taking a look, that he was there, supposing quitecorrectlyhat things would not have looked that way unlesshe was.

(This s not Dretske'sexample,but I hopeit does not botchhispoint.)The third point, implicit of coursein those others, is -that, whilein a sensewhat we can see is simplywhat is there to be seen, there isno such ineluctable limit to what we can 'get to know by visualmeans'. We can indeedget to know things by seeing that they arethe case; but there are also things that we can see to be the casejust becauseof, or on the basis of, other things that we know, andthat perhapswe got to know in quite differentways. The capacityto see, as one might put it, is a capacity of acquiring ' visual in-crements to a stock of knowledgethat is itself, by that means and

many others,indefinitelyextensible; so that there is no fixed pointbeyond which no further visual increment is possible, or beyondwhich any further ncrementwould have to be non-visual. Dretskegoes into this, with care and exactnessand (I wouldsay) truth, in along discussionof observation n scientificpractice.

It will be observed that this critical notice has not been verycritical,at least in that secondarysense of the term which connotesdisagreement. But I do not apologizefor that. This seems to meto be a book in which many, many things are got right, and which

accordingly, admirably,offers little occasion for the philosophicalsportofperpetualdissension. I shouldmention that it alsocontains,though I have not discussed,valuable passages about 'perceptualrelativity' and about measurement; and also, of course, aboutmany instances of seeing other than those which, as central cases,I have mentioned here.

G. J. WARNOCK

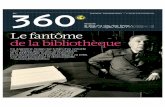

PHILOSOPHYAS LITERATURE:THE CASEOF BORGES

I. Borges he Artistand Borges heThinker

A LEADINGhistorianconfessedto me once that while he had beenacting editorof the journaldevoted to his sub-specialismhe had oneconstant nightmare: he feared he might accept for publication afabricated paper with fabricated documentation, so vast even ahistorical sub-specialism s. The nightmarerepresentsnot merely

an expression of anxiety due to ignorance of certain areas-itexpresses the terrible idea that the Cartesiandemon can fake anysymptomof reality and pass for real by any touchstone.

Jorge Luis Borgesis workingfor decadesnow on the execution ofthe nightmare. Perhaps his most celebrated instance is " Tlon,Uqbar,OrbisTertius". It would take much work to sift the fabric-ated referencesin Borges' works from the ones deliberately mis-read from the over-emphasison an author's casual remark, etc.

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 3/9

288 CRITICAL NOTICES:

This, of course, s part of the game, for Borgeswishesto shakein hisreader he commonsensical onfidence hat one knowsthe difference

between dream and reality-be this confidencebased on any in-tuition or on any criterionto demarcate the two. Consequently,tis very hard to demarcate Borges' stories from Borges' essays.If we read the story ' Funes the Memorious we may view it as ashort story or as a thought experimentabout a Lockian mind withtotal recall. Now that A. R. Luria has published an empiricalstudy of such a mind, one need not vindicate Borges, but may drawattention to additional treasuresburiedin his stories and essays.

Normally one separates stories and essays functionally. Theartist's task is to explore the emotional-experientialdimension.

Whena writerexploresa new vision of the world n order o openupa new feeling, a new attitude, he is writing as an artist. As anartist he can also take a platitudeand enhance t so as to make youfeel its full significance. As an essayist he would rather drawfromthe platitude conclusionsunexpected and unplatitudinous, or hewouldtake an unnoticed fact or an outlandishthesis and show itsmeritand significance.

This demarcations not clear-cut. In particular, here is the areaof overlap. Butler'sErewhonand ErewhonRevisited ncludeessays

thoughtful in their defence or mock-defenceof outlandish theses,but alsopregnantwith a quaintatmospherepeculiarto these novels.So are most of Borges'writings. Like Butler, Shaw,and others,heuses a literarymediumto advocatean unpopularphilosophy. Likethem he is in dangerof being valued as a writer of note but as anadvocate of a shallowphilosophy. The philosophyhe advocates isa variantof Schopenhauer's, nd muchakin to that of ErwinSchrod-inger, well-known as a physicist but hardly as the accomplishedwriterand the intriguing philosopher hat he was.

It is the Schopenhauerianprinciplein Borges which makes him

wonderwhat is real and what is illusoryin our commonexperience.And it is this which makes him deliberatelyblur the borderlinebe-tween his fiction and his essays: as if in order to imitate natureheblurs the boundary between reality and dream. The result mayeasily be that his essays be deemeda new form of fiction: besidesthe reportagenovel we may see the non-fictionnovel. The Englishtranslationof Borges' essays, Other nquisitions, ncludesa prefatoryessay of over seven pages, by James E. Irby of Princeton. Histhesis is that all Borges'essays are works of fiction, in the sense inwhichBorges'beliefsare ' clearlynot ' the onesseeminglyadvocatedin the essays. This, I am tempted to say, is 'clearly' an indicationof Irby's reluctance to accept Borges' challenge. In particularhe apparentlycomfortshimselfby reference o the fact that Borgeshimself is dominated by skepticism. This would not be the firsttime that the challenger's kepticism s usedas an excuse to maintainone's dogmatism. But, frankly, I do not think Irby's dismissalofBorgesthethinker s rooted n dogmatism; more ikely it is rootedin

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 4/9

J. AGASSI: The Case of Borges 289

fear of having one's ontological security put to test: whatever one

thinks of R. D. Laing and his The Divided Self, most psychologistsdo accept his idea that ontological security, i.e. a sense of a more or

less fixed identity, is important for most people as means of retainingtheir sanity. Now, it is not very rational to dismiss Irby's idea on

psychological ground-except that his idea is a dismissal of Borges'ideas on psychological cum literary grounds. And all I wish is to

present Borges as an interesting thinker.So let me take up only one of Borges' challenging ideas and show

that they can be put in a more sober, i.e. literarily inferior, manner sothat it may be harder to dismiss them as merely artistic exercises.

II. Borges'New Refutation f TimeThe idea which Jorge Luis Borges explores in the last of his Othler

Inquisitions is, he says, a mere anachronism. Supposing it to be so,

it would be, at the very least, a new and enlightening reductio of an

old system. Beyond that it may raise problems concerning current

philosophy. Let us take the historical point first, and conclude with

brief remarks on the contemporary scene.

Borges explains that in the tradition of the idealism of Berkeley

and Hume-and I should add perhaps, Ernest Mach and Russell of

the Analyses and even Carnap of the Aufbau-the attempts todeprive the world of its substance are intended to leave the world

as a system of experiences very much like the familiar ones. We do

not, along these lines, deny material things their being there, but

of their substance, says Berkeley; and so with minds, says Hume;

and so with space, say Berkeley and Hume; and so with time, con-

cludes Borges. With what consequences?

Berkeley and Hume consider fragments of space which are ex-

perienced by individuals. They map these experienced fragments intoa logical space, in a manner such that overlaps of these fragments

are faithful to experienced overlaps (e.g. you and he now observe thesame table, or desire the same woman). The whole lattice of ex-

perienced space, they hoped, will turn out to be a subspace of the

geometer's space; what of the geometer's space is left out, is the

unexperienced portions of geometrical space sliced out by Occam's

razor. Whatever Occam's razor can cut, the idealists may put as

their dictum, it should very well cut.

Borges observes that the operation of mapping experienced spaceinto the geometer's space presupposes simultaneity, that simultan-

eity presupposes objective or substantial time, and that hence the

idealist's program is not completed. Rather, let us replace simultan-

eity with experienced simultaneity. Similarly, let us replace the

past with experienced past, which is present memory. Let us see

what this further application of Occam's razor amounts to.

One immediate corollary is that not all simultaneously experiencedportions of space are necessarily mapped into the geometer's space

of the same real moment: all overlapping experienced portions of

10

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 5/9

290 CRITICAL NOTICES:

the geometer'sspace which are experiencedsimultaneouslyas over-lapping, will have to merge; the overlaps will be used to secure

proper mapping,much as we usually do it in aerial photography.When n aerialphotographywe have no overlapswe use othermeansof linkage; including conjecture, f need be. What will the idealistdo under such conditions? Suppose that mankind is split at onetime into various groupswith no experiencedcommunications,weshall not knowhow to correlate he various subspaces hey formandto projectthem into the geometer'sspace without first establishingsimultaneity. Of course, he various communitieswill later establishcontact and then will have, quite possibly, at least various groupsof memories,records, clocks, etc. This will provide the necessary

overlap to help them overcomethe difficulty and re-establishthetotal experiencedspace-time manifold into the geometer's space-time manifold. But this is quite an involved piece of undertaking,and there is no guarantee that while executing it nothing will beupset. So many things can go wrong!

In particular, what can go wrong is that time need not be aprogressionor a simple line; it can be a loop. If the wholeworldof experience s a loop (The Great Cycle), things might still be toler-able. If it is a loop for one memory sequence, then of necessity

(for topologicalreasons alone) the venture of mapping experiencedspace-time nto the geometer's pace-timewill fail. A loop may occurif one remembersa future event. A loop may occur if an extra-ordinaryexperience,say a dream,recurs. A loop occurswhen DonQuixote reads the Quixote,when Scheherezadetells the tale ofScheherezade. But say this is impossible(why?). What aboutanyordinaryrecurrence? If we have a time-axis proper we shall haveto speak of the recurrenceof a dream as well as of a sunrise as anevent separate from its previous occurrence,of Rip Van Winkleas different rom his son. But for this we need to assume the time-

axis first, namely, time regardlessof and priorto experience-per-haps even time as a substance. And if so, we may just as well takespace in the same manner. To house real space-time with mereexperiencesmakes no sense to any philosopher. Therefore,afterassuming real space-time we may well give up idealism altogether.

III. The Force of Borges'Criticism

Borges says that he assumes the principle of the identity ofindiscernibles. This is true, strictly speaking. Is it, perhaps, a

principle hat the British idealists wouldreject? Will this, perhaps,invalidate Borges' criticism? I think not. I think the Britishidealists assume, and have to assume, the principleof identity ofindiscernibleshough, admittedly,they need not stress it overmuch.Whatthey speakof is experience,andthe identity they assume s theidentity of experiences,not of things. Once you allow the multi-plication of one experienceat will, the Occam'srazor is bluntedand the strongestcase for British idealism is given up.

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 6/9

J. AGASSI: The Case of Borges 291

Assume, however, the identity of indiscernibles. Assume also,with Berkeley and Hume (paceChesterton and Borges), that our

stock of possible experiences in all their combinations is finite.(Berkeley and Hume clearly declare all experienceable space,geometrical,colour,sound, etc., to consist of a finiteset of discretesegments. And so, it seems, dideven Wittgenstein n his Tractatus.)It followsthat quitepossibly(and in the long runcertainly)simultan-eouswith my presentexperiencehere, thereis an identicalexperienceelsewhere. We need not fear, however,that these two have to beconsidered dentical; they belong not only to differentparts of thegeometer's space (which the idealist denies the existence of) buteven to differentparts of experiencedspace which, we remember,is mapped into the geometer'sspace. And so the idealist and thegeometer will come up in this case with the same result-to theidealist'sdelight.

But in order o groundthis commonsense n idealism, for all cases,idealists must assume certain suppositions. They must assume,first, that each experiencedsegment of space is Euclidean or somesuch-is topologicallydecent. This they do, and on the authorityof commonexperience,they say. They must likewiseassumethatthe lattice of all overlappingexperiencedsegments is Euclidean

or some such-is also topologicallydecent. The second assumptioncannot, eoipso,rest on experience. It can thereforebe questioned.It turns out to be highly questionable: the topology of the latticeneed not coincide with the topology of its elements. (Einstein'sspace is Euclideanlocally but not globally.) Given the principleofidentity of indiscernibles rOccam's azor,wemustrejectthe dealist'sassumptionthat the sum of Euclideansubspacesis Euclidean.

And so idealism ends up with loops, both in space and in time;space-timebecomes a lattice with a topology of a most curiousandunexpected nature. Subsequently one must reject one's sense of

identity as illusory. And so the British idealist's programme ofleaving the world of experienceas it is fails and the world all of asudden is experiencedas an eerieplace. End of argument.

What has gone wronghere? Borgeshimself is an idealist of thesame school as Schopenhauer and Schrodinger. What he findsotiose in the British empiricist's dealism is not its being idealisticbut its being so reassuring,commonsense,flat. (This incidentallyis what he, following Shaw, views as the most eerie and unrealthing-hell indeed.) But what he rejects in British empiricism

most strongly is not so much that it flattens the universe,but, andmore deeply, that it denies the existence of a limitation on reason;not so much that it identifies the knowable with the observable,but, andmoredeeply,that it identifies he knowablewith what thereis. Borgeshimself is all too awareof his own message: the worldis not, in principle, ully knowable. He is no less awareof lacunaeand difficulties n his own philosophy. Destroyall sense of identity,and the sense of self-identity, perhaps even of responsibility, is

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 7/9

292 CRITICAL NOTICES:

gone as well. And that will not do. ' The world, alas, is real;I, alas, am Borges.' So concludes he essay.

Now it is not as if we have the choicebetweenrealismand Schopen-hauerianidealism without a clear sense of identity. The a priorispace-time necessitated to avoid loops need not be objective-itcan very well be a Kantian form of intuition, assumed ndependentlyof the question, does objective space-time exist. Borges, likeSchrodinger, inds here a greatmystery: how is it that different in-tuitions agreewith each other. This,incidentally, s alsoof historicalinterest: Kant's challenge n the directionof non-Euclidean eometryis better known than his challengein the directiontaken up laterby Schopenhauer-partly at least because the latter was not takenseriously n his lifetime or soon after.

It is therefore hardly surprising hat both followersof Schopen-hauer, Schrodingerand Borges, come up with two similarviews onmatters of space-time in relation to identity. Let me quote onlythreeextracts fromstrikingpassages n one of Schrodinger'strikingbooks (My View of the World): ' Shared thoughts, with severalpeople really thinking . .. are singleoccurrences. .' (p. 17). 'Areyou dreamingme and everythingelse, and am I dreamingyou andeverything else, so cleverly that our dreams match? But this is

merefoolishplaying with words' (p. 105). 'The hypothesisof thereal world does at least explain some of these various degrees ofsharedness n a naturalway, because it includes the reality of spaceand time.... Thedoctrineof identity requires omevery penetratingthinking in order to make these distinctions [between seeminglydifferentselves, such as I and you] plausible, thinking which hasneveryet, perhaps,been properlydone.'

A similarplea forrethinkinghas beenmadeby CharlesHartshornein the first issueof The PhilosophicalForum,1968-69,whereidealismis advocated without the eighteenth century sensationalismwhich

traditionallygoes with it.

IV. The Problemof Individuation

The aimof Borges s to impartto hisreader he sense of the mysteryof the world, a sense of skeptical reverence, akin to Einstein's" cosmicreligiousfeelings". For this, as a man of letters, he mayuse any means at his disposal,includingmagic and mysticism, andincluding ogic, valid or somewhatfaulty. It is amazinghow sharpandforcefulboth his magicand hislogichappento be. Philosophers

seldom expect a magically minded man of letters (' I always tryto accept naturalistic explanations , he says wrily) to use validlogic; muchless in a revealing ashion. I have thereforeundertakento translate his literary gem into the cruder language of a merephilosopher. There s, I think,a strongphilosophic eason n Borges'dual theme of the mystery of time and of blurredidentity: likeSchr6dingerhe feels that we need a theory which will account foroursenseof multiplicityof things, even will groundthem in reality,

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 8/9

J. AGASSI: The Case of Borges 293

yet will deny, in the last resort,the existence of morethan one finalentity. Borges, thus, is more intent on raising a problem, albeit

from a given philosophical (Schopenhauerian)viewpoint, ratherthan advocate his philosophy.

This,it seems, s of universalvaluein our own days. The problemof individuation does these days engage an increasingnumberofphilosophers. We can say, briefly, that extremelyfew solutions toit are known, all unsatisfactory. First, and foremost,Parmenides'solution: there is only one thing. This leaves roomfor no explan-ation of the phenomena. Second, Spinoza's variant of the sameidea of Parmenides. This simply sidesteps the problemof individu-ationcompletely: we know whatis an attribute, but what determinesa mode? There is the class of solutions-of Democritus and Platoand Mach and Haldane: individuals are atoms of reality, be theyindivisible particles, or qualities, or sensa, or genes; so-calledindividuals are conglomeratesof atoms. A corollary o this is thatany so-called ndividual, whethera personor a world,is repeatable.ThisconclusionDemocritusaccepted,Plato found(inhisParmenides)unacceptable,Mach foundtantalizing since vergingon the mystical(and so perhaps did Wittgenstein, Tractatus, 4.014, though not2.0233), and Haldane found disturbing. For my part I see little

need to argue that neither the Parmenideannor the Democriteansolution will do. Clearlythe only promisingsuggestion, thus far,is that there are levels of identity. This solution, Schr6dingerclaims, is Schopenhauerian.

Identity is deeply linked with space-time,as a brief deliberationon Leibniz's two proofs of the identity of the indiscernibleswillindicate(now that we have Borges'new refutation oftime). Leibnizproves the principlefirst from God'somnipotenceand secondfromfact that the differentspace-time coordinates of two things makesthem non-identical. Now Leibniz denied that space-timeis a sub-

stance, even that it is strictly Euclidian; but he went no further.Assume the two proofs valid, and two identical things of differentcoordinates must belong to a loop in space-time! There is littledoubt that such considerationsmust enter Einsteinian cosmology,since Einstein was, on this issue, a Leibnizianproper. Identifyingan entity and decidingthe topology of the cosmosmust be deeplylinked procedures. This, as Schr6dingerobserves(p. 76), opens anew link between relativity and quanta-via the Pauli-Dirac ex-clusionprinciplewhich is a principleof individuationof sorts.

Boston University J. AGASSI

BIBLIOGRAPHY

J. Agassi, The Place of Leibniz n the Historyof Physics , Journal ortheHistory of Ideas, vol.29 (1969).

JorgeLuisBorges,FiccionesEvergreen, ewYork,1966).

This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Mon, 14 Oct 2013 20:01:28 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

7/27/2019 Borges - A Case of Philosophy

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/borges-a-case-of-philosophy 9/9

294 CRITICAL NOTICES:

Jorge Luis Borges,Labyrinth8, electedstoriesand otherwritings, editedbyDonald A. Yates and James E. Irby, Preface by Andre Maurois,

paperback(New Directions,New York, 1962).Jorge Luis Borges, Other nquisitions,1937-1952 translatedby Ruth L. C.

Simms. Introduction by James E. Irby (University of Texas Press,1965), paperback(New York, 1966).

Jorge Luis Borges, A PersonalAnthology, orward by Anthony Kerrigan,Grove Press (New York, 1967).

R. S. Cohen, "Ernst Mach: Physics, Perception, and Philosophy ofScience", Synthese,18, 1968.

A. Einstein, Prefaceto M. Jammer,Concepts f Space(HarvardUniversityPress, Cambridge,1954).

Daniel E. Gershensonand Daniel A. Greenberg, The " Physics " of theEleatic School: A Reevaluation', The Natural Philosopher,vol. 3(BlaisdellPublishing Co., New York, 1964).

Charles Hartshorne, ' The Case for Idealism', The PhilosophicalForum,Boston, vol. 1 (1968).

J. B. S. Haldane, ScienceAdvances GeorgeAllen and Unwin Co.,London,1947).

David Holbrook, 'R. D. Laing and the Death Circuit', PsychiatryandSocial Science Review, vol. 3, no. 4 (April 1969), reprinted fromEncounter,August, 1968.

A. R. Luria, TheMind of a Mnemonist:A LittleBookabouta VastMemory,

translatedby L. Solotaroff (Basic Books, New York, 1968).Erwin Schrodinger,My View of the World, ranslatedby CecilyHastings

(CambridgeUniversity Press, 1964).L. Wittgenstein, TractatusLogico-PhilosophicusLondon,1922).

TheRevolutionn EthicalTheory. By GEORGE C. KERNER. Oxford:The ClarendonPress, 1966. 40s. Pp. 251.

PROFESSOR KERNER is of that incorruptibleine of moralphilosopherswhohave set aboutconfrontingHume'sconclusion hat moraljudge-ments derivefrompassionand arenever n accordwith or contrary oreason. To this endeavour he brings a conception of our moralutterancesas linguisticacts, a conceptionwhichwill allow us to see,he believes, that they can have certain " proofs". (The invertedcommas,commendably,are his own.) Proofs of this kind are saidto be conjoined,when necessary,with a defenceof the competenceofthe provers,who must, it appears,claimfor themselvessomeof thoseexcellencessometimesattributed to the Ideal Observer. ProfessorKerner'seventual presentationof this doctrine is inventive, schem-atic and cautious,morecautiousthan the announcementsof it in theearly parts of the book.

Therevolutionmentioned n the book'stitle is the concernof recentphilosopherswith the analysisof moral anguageand their abandon-ment of moralmetaphysicsand a good deal else. The revolution-aries are Moore,whose somewhatdubiousinclusiondependspartly

Thi t t d l d d f 144 82 108 120 M 14 O t 2013 20 01 28 PM