Blackbright dec jan blackbright 2013

description

Transcript of Blackbright dec jan blackbright 2013

BlackBlack -- BBrr ii gghh tt(A Bespoke Approach to Empowerment)(A Bespoke Approach to Empowerment)

news

TM

Issue 39

ISSN No. 1751-1909

Blackbright News Magazine

Registered Office

Studio 57 LU2 0QG

Tel: 01582 721 605

email: [email protected]

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Founder & Managing Editor

Myrna Loy

Logo Design: Flo Alowaja

Photos taken from Google Images

Graphic Design: M Loy

For previous issues go to:

www.issuu.com/blackbrightnews

Printed by Mixam (UK)

DO YOU LIKE BLACKBRIGHT NEWS?

Would you like to suscribe, donate

or sponsor the publication?

email: [email protected]

www.facebook.com/blackbrightnews

What’s Inside...?

- How do the police protect

and serve us? (Editorial)

- An Explantion of Death

in Custody (P.7)

- A Man with a PhD

Dr Lez Henry (P.9)

- What do you want to be

when you grow up? (P.12)

- Unconditional Love (P.14)

- Did you know (P.15)

BLACK-BRIGHT NEWSStimulates – Educates – Motivates

Black-Bright News recognises that welive in a world where we can be adverselyimpacted by what is going on around us orwhat is being said to, or about us, whichcould distract us from nurturing our attrib-utes and skills or pursuing our dreams andambitions. Many of us are discouraged bybarriers, or we allow media, peer pressure,values, or social engineering to influencehow we should behave or react; or biasand prejudice to dictate our perception ofourselves.

Black-Bright News intends to redressthe negative stereotype by changing per-ceptions that are incorrect, while at thesame time, motivating the disenfranchisedand demotivated. Subliminal messagescontinue to be perpetuated through mediato distract the unaware from their vision.Disenfranchised individuals can be madeto believe they are unable to accomplishtheir goals. Black-Bright News aims toreframe concepts and empower readersby publishing information that is represen-tative, stimulating, relevant and inspiring.

Black-Bright News is an empowermenttool that promotes a healthier mindset bysharing positive experiences; the benefitsof education; the motivations behind suc-cessful people and the consequences oflifestyle choices, so that the misguided orconfused can make informed choices thatare beneficial to them.

In partnership with Blackbright Commu-nity Services Limited, (which is an Out-of-Hours Social Enterprise that offers aCounselling & Advisory Service) individualscan receive information, counselling, me-diation, advocacy, advice and outreachservices, or can be signposted to a special-ist/organisation who is more qualified to

empower and assist.

www.issuu.com/blackbrightnews

www.blackbrightcommunityservices.com 3

BLACK-BRIGHT NEWS

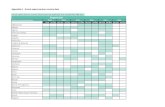

SUBSCRIPTION FORM

YES! I would like to subscribe to Black-

Bright News

[ 2 hard issues + 6 soft issues£20.00

[ ] 4 hard issues + 12 soft issues£40.00

Mr/Mrs/Ms/Miss

Full Name:

Address:

Post Code:

Email Address:

TERMS & CONDITIONS:

Subscriptions are non-refundable.

Cheques are made payable to Black-Bright Community Services Mail to: 57 Saywell Road Luton LU2 0QG

To pay by Paypal, simply send your emailaddress to [email protected]

Black-Bright NewsStimulates - Educates - Motivates

(Informing the Vulnerable ,

Demotivated and Disempowered)

Tel: +44 (0) 1582 721 605

Subscription includes a minimum of one Limited

Edition and electronic versions.

4

most of the members of the IPCC are ex-police offi-

cers or ex-officers of other regulatory systems, the

organisation shows its loyalty to the offending police

officers it is supposed to investigate, as opposed to

the complainant, whose interests it should have at

heart.

After hearing about the tragic

and unnecessary police re-

lated deaths of Shiji Lapite,

Sean Alder, Alton Manning,

Sean Rigg, Michael Powell,

Mark Duggan, Jacob Michael, Azelle Rodney, Jimmy

Mubenga, Frank Ogburu, Smiley Culture, Demetre

Fraser and Leon Briggs, to name a few, and female

deaths inside police institutions, which include

Helen Cole, Sarah Campbell, Nisa Anne Smith, Va-

lerie Hayes, Lisa Marley, Julie Walsh – the list goes

on, it is very disconcerting! It is a fact that CCTV

cameras are rigged to conceal evidence. Corrupt po-

lice officers implicate the whole police force, forcing

the public to lose faith and confidence in the police

service.

Docherty informed me that there had been around

’6,000’ police-related deaths, as at 2012, and not

one police officer has been prosecuted!! Spliced

CCTV reels; perjury, collusion, non-compliance with

the ‘Golden Hour’ hate crime and racism are reasons

why the police are not prosecuted. The Crown Pros-

ecution Service jailed police woman, Rebecca

Swanston, for leaking intelligence to her 4 lovers, yet

no-one is jailed for Corporate manslaughter!

Editorial

As my regular readers know, my daughters and I

present a radio show called Straight Talk (currently

on a Saturday) on Jamrock Radio, which discusses

issues that inform our community.

In November, I interviewed Michael Docherty be-

cause I heard he had been an eloquent speaker at

a collaborative event, put together by Lenos Wil-

son of Non-Violence Alliance at the UK Centre for

Carnival Arts based in Luton. Nearly 300 members

of the black community attended that meeting in

anticipation of discovering what had happened to

34 year old Leon Briggs, who died in police custody

hours of being taken in. Michael Docherty, who is

a Civil Liberties Campaigner and Founder of Justice

Now, had experienced, first-hand, police miscon-

duct and abuse of power, and since this was the

premise that suspicions were built on, it seemed

appropriate to bring him in for an interview. At the

time of writing this editorial, Michael Docherty is

the first individual to privately prosecute a police

civilian and win. The interview can be found at

http://blackbrightnews.podomatic.com.

It was interesting to learn during the interview,

that whenever there is a death in custody, the po-

lice have to call in the Independent Police Com-

plaints Commission (IPCC), whose statutory

obligation is to secure and maintain public confi-

dence in the system of complaining against the po-

lice’. However, Docherty believes that because

Docherty is campaigning for an Independent

Watchdog to police the police, like they do in

Canada.

Then, only days later, I heard Janet and Frank

Robinson on BBC news share their disappoint-

ment in the cover up of their son (John)’s death,

when Staffordshire Hospital misdiagnosed a rup-

tured spleen by saying he was suffering from

bruised ribs. He died hours afterwards, and the

Robinsons are angry and insulted by the NHS’s

subsequent cover up.

Francis Report: “to err is human to cover up is un-

forgiveable!” which is my bone of contention, be-

cause if ‘people at the top’ are covering up, lying

and deceiving, what kind of example are they set-

ting for our young.

We grow up witnessing the exposure of those in

power found guilty of committing fraud; having

extra-marital affairs; lying and deceiving the public

to protect their reputation, income or to prevent

paying out compensation and when little Joe Pub-

lic makes a mistake, he or she is hung out to dry

and made a spectacle of, while the big wigs get off

with a pat on the back, a large pension and a

transfer to a different area or a another high-paid

position!

According to Simon Chauchard of Oxford India

University, “the frequency with which alleged or

convicted criminals manage to gain public office

threatens the ideals and the functioning of the In-

dian democracy”.

It is clear that we live in a collusive society where

many who are recruited to serve and protect are

guilty of lies and deception, how do we change

this deceptive culture?

Editorial by Myrna Loy

Bayard Rustin...

“The Negro struggle has

5@Blackbrightnews

6

Bedfordshire Police continues to call for the public to

support the fight against gun crime with the mes-

sage: ‘Bedfordshire Police is making a statement

about gun crime – are you? If you want action, make

your words count’.

The message is supported by the Police and Crime

Commissioner and Luton Borough Council as part of

a much wider range of enforcement, reassurance

and community cohesion activity going on in the

town. It is designed to provoke people with informa-

tion about incidents, where firearms or violence

have been used, to put pen to paper and make a

statement.

“Since the murder of Paul Foster in April 2013 Luton

has witnessed an unusual and worrying increase in gun

related and violent crime,” said Chief Superintendent

Mark Turner. “That is now being addressed and

brought under control but with further help from the

public we can ensure an even safer Luton for everyone.

“We continue to ask Luton residents to be brave and

make statements that will help us bring people to jus-

tice. We understand that putting yourself forward in

this way could cause concern but we want to reassure

people, it might be as simple as a confidential conver-

sation but if it is concerns for yourself or family then

talk to us about it, we have measures we can put in

place to address these fears and anxieties,” he added.

Police and Crime Commissioner Olly Martins said:

“The conviction of Kyle Beckford earlier this year

showed the value of the public passing on information.

Without key pieces of evidence, that result may not

have been possible.”

What Statement

are you making?

Claude McKay (Poet)

“If we must die—let it not be like hogshunted and penned in an inglorious

spot. Oh, Kinsmen! We must meet the common foe;

Though far outnumbered, let us showus brave, and for their

thousands blows deal one death-blow!What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

7

AN EXPLANATION OF DEATH IN CUSTODY

Rebecca Broadbent explains the contentiousissue of death in police custody and theprocess for investigation, prosecution andinquests into the incidents. Source:www.thestudentlawyer.com

Custody can be defined as an authorisedform of state detention. The term thereforeincludes:

Police custody (if an individual is under ar-rest in a police station, or detained for thepurposes of a search), andPrison custody (if somebody is serving timeon remand, or if somebody who has alreadybeen convicted and sentenced is serving acustodial term in a prison).

What is a death in custody?Quite simply, a death in custody is a deathwhich occurs in state detention, whetherthat be in police custody, prison, or someother form of detention centre. It includesboth deaths of natural causes and suicides.

In fact, deaths in or following policecustody are considered one of the mostcontroversial areas of policing…

DEATHS IN CuSTODY: A CONTENTIOuSISSuEDeaths in custody are a contentious issue,particularly so in the context of police cus-tody. In fact, deaths in or following policecustody are considered one of the most con-troversial areas of policing and make upsome of the most high-profile cases consid-ered by the Independent Police ComplaintsCommission (IPCC). The IPCC is a body, to-tally independent from government and thepolice, which deals with police complaints.

Deaths in police custodyDeaths in police custody influence publicconfidence in the police. We like to think thatthe police always operate in good faith.However, when someone dies in police cus-

A £2000 reward is still on offer from Bedfordshire Police

and Crimestoppers, to anyone who provides information

that leads to the arrest and conviction for gun crime.

Anyone with information relating firearms offences can

contact Bedfordshire Police, in confidence, on 101, or text

information to 07786 200011. Alternatively you can con-

tact the independent charity Crimestoppers anony-

mously, on 0800 555 111.

tody, it can raise legitimate questions as to theirtreatment whilst detained. This is one of the rea-sons why an inquest is necessary after an indi-vidual dies in custody.In addition to the necessity of an inquest, alldeaths following either police contact or policecustody must, by statute, be referred to theIPCC. Based on these referrals, the IPCC pro-duces an annual report consisting of the statisticsrelating to the deaths. Recommendations as topolicy and practice are then given by the IPCC.Deaths in police custody can arise out of the fol-lowing circumstances:

Unlawful killing by police officersThe use of excessive force by a police officerDeath by alcohol or drugs poisoningSuicideTraffic accident with the policeNegligent treatment whilst in police detention.

The annual reports of the Commissioner of thePolice for the Metropolis and HM Inspectors ofConstabulary suggest that in most cases whereindividuals die in police custody, there is no sug-gestion of any misconduct on the part of the po-lice.

DEATHS fOLLOWING CONTACT WITH THEPOLICEDeath following contact with the police encom-passes those situations where an individual diesafter some form of interaction with the police.Contact with the police could therefore include:Direct contact, assault, or physical interaction(although it is not limited to this by any means)Checking the welfare of a homeless individual byofficers. The release of an individual by a custodyofficer on bail.

In transit from police detention, to another place,including hospital.

However, when someone dies in police cus-tody, it can raise legitimate questions as totheir treatment whilst detained.

CORPORATE MANSLAuGHTER AND POLICECuSTODYWhen a prosecution relating to a death in policecustody is contemplated, the prosecutor may

8

consider it relevant to charge the offence as acorporate manslaughter offence if:

The death occurred in custody andThe organisation owed the detainee a duty ofcare.

Section 2(2) of the Corporate Manslaughter andCorporate Homicide Act 2007 lists various insti-tutions and circumstances and, if an individualfalls within these, he is owed the duty of carestipulated in section(1)(d) of the Act. These in-clude:

If an individual dies as a result of misconduct, hisestate is entitled to pursue a civil action againstthe police.Detention at a custodial institution, or in a cus-tody area at a court or police station.Detention at a removal centre or short-termholding facility.Transportation in a vehicle, or his detention inany premises, in pursuance of prison escortarrangements or immigration escort arrange-ments.Placement in secure accommodation.Detention as a patient.If the death occurred whilst in custody and a cor-porate manslaughter prosecution is anticipated,the case should be referred to the Special Crimeand Counter-Terrorism Division (SCCTD) for han-dling. This is the body which prosecutes deathsin custody cases too.

DEATHS ARISING OuT Of POLICE MISCON-DuCTIf an individual dies as a result of misconduct, hisestate is entitled to pursue a civil action againstthe police. Any cause of action he may have hadin relation to his treatment survives his death.Additionally, certain family members can sue forany loss or damage they have suffered as a con-sequence of the death (Kirkham v Chief Consta-ble of the Greater Manchester Police [1990] 2 QB283).

DEATHS IN PRISON CuSTODYPrison authorities own a common law duty ofcare to prisoners to protect them from criminalacts and from self-harm and suicide. Article 2

9

ECHR places a positive obligation on such author-ities to protect a prisoner’s right to life, by, for ex-ample, taking preventative operational action. Allprisons are expected to have local policies andstrategies in place to respond to a death in cus-tody.All deaths in prison custody are subject to the fol-lowing:A police investigationA criminal investigation, if necessaryA coroner’s inquest, andAn investigation by the Prison and Probation Om-budsman.

The investigation

If it transpires that any person or body is crimi-nally responsible for the death of that individual,the potential for punishment must be identified.

If the death occurred in police custody, or follow-ing contact with the police, the body which inves-tigates the death is the IPCC.If the death occurred in prison, or other detentionwhich was not police detention, the police will in-vestigate.

All investigations must be thorough. If it tran-spires that any person or body is criminally re-sponsible for the death of that individual, thepotential for punishment must be identified.

The prosecutionIf a prosecution becomes necessary in relation toa death in prison custody, the case is prosecutedby lawyers in the SCCTD. When prosecuting, it isimperative that the relevant prosecutor has nothad any previous dealings with any individual whomay be a suspect, and is totally independent fromthe police.

The inquestWhen an individual dies in custody, his deathmust be reported to a coroner. A coroner is alawyer or doctor who investigates the cause ofdeaths which are referred to him.If a prosecution for murder or manslaughter in re-lation to the death is being considered, the coro-ner will open an inquest, but it will be adjourneduntil the outcome of the criminal proceedings hasbeen determined.

If the prosecutor decides a charge is not appro-priate, the coroner must be informed of the deci-sion and the reasons behind it. The inquest thenproceeds.

HOW OfTEN DO PEOPLE DIE IN CuSTODY?In the 11 years between 1 January 2000 and 31December 2010, 5,998 deaths in custody wererecorded and reported. This is an average of 545deaths per year.

DR LEZ HENRY (Black with a Ph.D)

Dr William Henry was born in Lewisham of Jamaican

parents, his mother was a qualified machinist who

worked in a factory; his dad was a farmer who ended up

working on British Rail. Growing up in Lewisham he al-

ways had the support of his parents in whatever ventures

he embarked upon. “I can give credit to both my parents

for teaching me (and my siblings) where we are, how

we’re perceived in society and why we need to achieve

as much as we can” says Dr Henry.

Dr Henry is a writer, academic, public speaker and com-

munity activist who has been interviewed extensively by

both British and foreign media. The author a number of

books on race, culture, history, music and politics, he is

also one of the pioneers of British Reggae-dancehall

Deejays.

Dr. Henry is also a Social Anthropologist who lectured in

the Department Of Sociology, Goldsmiths College. With

a keen passion to give back to the community, he has

had first hand experience of supporting mental health

service users and has spent time working as the Centre

Manager for one of the oldest African, African-Caribbean

Mental Health organisations, Family Health Isis, is

based in south east London

Although a naturally talented person from a young age

(he and his brother were both tested academically suit-

able enough to go to a local grammar school), he was

forced to go to the local comprehensive school, Samuel

Pepys - now Crossways Academy, on account of his skin

colour. “This experience brought home to me how racist

this society was,” Dr Henry affirms, “the school itself was

nicknamed Sambo Peeps due to the high number of

black boys who studied there.” In spite of having the ca-

pability to perform well at school, Dr Henry felt he did not

agree with some aspects of the British educational sys-

tem, which, in his view, “taught us that blacks achieved

nothing in history”.

As an escape, he ended up taking courses in black his-

tory at Moonshot Youth Club, and at 15 was introduced

to African history and black contributions to the world’s

development, as well as studying martial arts to create a

mind/body balance. This focus on the African contribution

helped give him a sense of identity. He felt that “as a child

there’s a certain amount of confusion within the system

as to whom we’re supposed to revere educationally (in

the typical British education system).”

After being expelled from both school and college for

fighting, Dr Henry initially started work as a clerk in solic-

itor firms and banks after taking career aptitude tests. At

18, however, Dr Henry trained as an industrial pipe fitter

and was for a while a self-employed plumbing and heat-

ing engineer. This never stopped his passion for learning

nevertheless, “I’ve always been into self-education and

literature; I have completed plenty of courses which don’t

have officially recognised qualifications.”

After those years of experience, Dr Henry enrolled on an

Access course at Goldsmith’s College, University of Lon-

don, going on to complete a BA in Anthropology and So-

ciology, then heading straight into intense PhD study.

Even as a mature student, he faced frequent mockery

and subtle discrimination - “People frequently questioned

my being there.... even the tutor as well as the students

laughed when I informed them I intended to get a PhD

from that course.”

In 2003, he finally qualified as a social anthropologist,

briefly becoming a Visiting Research Fellow and lecturer

at Goldsmith’s Department of Sociology. Already a self-

taught individual, Dr Henry cited his attraction to sociology

from the application of theories and models being applied

to society. Because of his earlier passion for learning

alongside his jobs, he felt he was there purely for the the-

ory and models as opposed to being educated in a con-

ventional way.

It was during his PhD study that Dr Henry and his wife

and friends set up Nu-Beyond. Established in1998, Nu-

Beyond is an independent organisation which continues

to seek out and remedy the factors which exacerbate the

tensions between various communities, whether they are

racial, sexual or class-driven patterns of behaviour. The

organisation hopes to tackle these problems in a way

which provides an example of self-reliance that leads to

self-determination. Its programmes focus on the special-

ities of education, race, ethnicity, diversity and social, cul-

tural and political empowerment. He cites his old mentor

Professor Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe (who he met in Lewisham

as a young man) as the main inspiration behind Nu-Be-

yond.

Through Nu-Beyond, Dr Henry also organises sessions

called ‘BLAK Friday’. It was set up in 2006 ahead of the

2007 anniversary of the Atlantic slave trade - “a space to

present alternatives to the ‘Wilberfarce’ promoted widely

for the ‘white saviour’ of helpless black slaves without ac-

knowledging the activism of blacks in the emancipation

process.”

A project with a more contemporary focus within Nu-Be-

yond is the ‘Guns, Gangs, Family and Community’ proj-

ect, offering training for youth services, presenting

practical solutions to serious problems for black and wider

communities within the UK. “Unlike research projects

from various organisations, we focus on strong ground-

work and connecting people with training and work rather

than compiling pages of research which on the ground

tends to be useless,” says Dr Henry.

From his work, Dr Henry has diagnosed some of the

biggest obstacles facing young black youths today is the

problem of people not knowing what they’re being edu-

cated for and not grasping the fundamentals of education,

as well as lacklustre parenting. “Some black parents don’t

take on the mantle of responsibility for raising their child,

wrongly heaping that responsibility onto the teacher.

Some kids think they can resurrect their life in college

even after performing poorly in school. They don’t under-

stand the educational relationship.” He also points to an

increasing acceptance by black young people that being

stupid is cool. “In my day (the 1970s) I was determined

to appear smart in school; now it’s the other way, some

among black youth unfortunately seem to revel in being

seen as stupid and underachieving. Sometimes these

kids don’t know what they’re being educated for.”

A friend of prominent black academics and writers such

as Paul Gilroy, Robert Beckford and Linton Kwesi John-

son, Dr Henry is a firm critic of the disproportionate num-

ber of ethnic minorities in prominent institutions such as

the media, finance, politics and the law. 10

11

Speaking about the reception of him and his colleagues,

Dr Henry says “We are definitely sidelined in favour of

mainstream white academics and writers.” Broadening

the argument to the aforementioned institutions, he con-

tinues “A black kid who achieves AAAB at A level will gen-

erally find it a lot harder to get into a top university

medicine course than a white kid who achieves all Bs.

The professionals who choose the prospective students

need to change their attitude to how they select their stu-

dents. We need to remedy the impression that a middle

class white Oxbridge graduate is somehow more intelli-

gent than an ethnic minority pupil from the inner city. I en-

courage black people of all ages to study at universities,

as once we attain top qualifications and influence in em-

ployment, we will form a critical mass which no one will

be able to ignore.”

Dr William has also gained the reputation as an interna-

tional speaker, lecturing at many institutions including Uni-

versity Of The West Indies, Department of

Literature-Reggae Studies Unit, Mona Campus, Kingston,

Jamaica, WI: University of Gothenburg: Centre for Cul-

tural Studies, Gothenburg, Sweden. The African American

Studies Department, Yale University, Connecticut, USA.

Queens University Belfast: Department of Ethnomusicol-

ogy, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Howard University: Depart-

ment of Humanities, Washington DC, USA and African

And African American Studies Program, University Of

Oklahoma: Tulsa, USA.

As an international lecturer, Dr Henry cites the University

of Oklahoma as having the biggest impact on him. “My

visit there introduced me to an area called the ‘Black Wall

Street’ or as the Ku Klux Klan called it, ‘Little Africa’. It

was set up as a blacks-only area, as a result of segrega-

tion. Ironically, it was the best thing to happen to that com-

munity as they demonstrated that they were very

autonomous, self-reliant and prosperous without having

to rely on handouts and assistance by whites. Unfortu-

nately it was burnt and looted within a day on June 1st

1921 by the KKK as they noticed its growing prosperity.”

The model of the Black Wall Street is a model which DrHenry would like to see developed in communities over

here.

As far as his plans for the future are concerned, Dr Henry

says “Just do what I do and hopefully get paid for it!�

What do you want to be when

you grow up?by Chris

Primary school, secondary school, undergraduate

degree, postgraduate study – many PhDs have

spent their whole life working towards goals that

are education related. It’s natural to think of an ac-

ademic position as the logical next step or culmi-

nation of all those years of work. And yet, it’s also

worth taking some time out to reflect and ask our-

selves, by completing a PhD, have we actually

achieved what we originally set out to do? What

else do we want to achieve in our lives?

These are important questions, because each of us

has hopes, dreams and ambitions that help to drive

us on, or which we’ve not yet fulfilled. Knowing

what motivates us is important as we approach the

end of our PhD, because these hopes and ambi-

tions can help us to generate options for career

paths outside of academia.

So take 15 minutes out of your day to reflect upon

the following topics:

1. Childhood dreams. Think back to when you were

a child. When grown-ups asked you ‘what do you

want to be when you grow up?’, what did you

say? Did you want to become an professor or re-

searcher? Write down your dreams, however fan-

tastic or mundane they sound. Is now the right

time to begin to realise those dreams? Can you

pursue a career path that will help to make your

dreams come true?

2. Ambitions. As we grow up we develop ambitions

and goals that we strive to achieve. What were, or

are, your ambitions? Financial – make enough

money to live comfortably? Environmental – save

the world? Have you put your ambitions on hold

while you take the time ‘get your qualifications’?

Now that you’re in sight of completing your PhD,

is it time once again to focus on achieving your

personal ambitions? Jot down your ambitions and

consider the career path that would best help you

to realise those ambitions.

3. Challenges. Sometimes we set ourselves chal-

lenges in life – or they are set by other people for

us. Maybe someone once challenged you to ‘get a

proper job’? Maybe you’ve sat too long at a desk

and want to master the art of gardening? What

about running your own ethical business? Walking

to the North Pole? Write down some challenges

that excite or frustrate you. How could you tackle

and overcome these challenges after completing

your studies?

Having spent some time reflecting on these topics,

think about where you are now in your life. De-

spite everything that you’ve accomplished (and a

postgraduate degree is a tremendous achieve-

ment), do you still feel a sense of unfulfilment?

Could you feel more fulfilled if you took steps to-

wards realising one of the dreams, ambitions or

challenges that you’ve noted down? Think also

about the people who matter to you, and how they

might be surprised, but also full of admiration, if

you took bold steps towards achieving a personal

dream or ambition.12

Photo above from Generating Geniuses (TonySewell)

There are no right or wrong answers to this exer-

cise. Exploring these aspects of your character

will help to confirm that academia is right for you,

or bring to light potential career paths outside of

academia.

http://jobsontoast.com/how-to-realise-your-dreams-and-am-

bitions/

13

Positive Roots Consultancy is aFamily Welfare/Support organisation thatseeks to empower individuals & commu-nities to lead a healthy and violence freelifestyle both in the UK and abroad. Thestaff team at Positive Roots ConsultancyLtd comprises of criminologists, socialworkers, probation officers, parentingpractitioners, youth workers, psychother-apists and life coaches. We are specialistsin addressing issues relating to all formsof abuse including parent to teen violence,domestic violence, sexual exploitation/sexualised behaviour & child protectionconcerns. Our services also extend toworking with offenders & those at risk ofoffending. Positive Roots provide theseservices to parents/carers, children/youngpeople & all health, social & criminal jus-tice professionals working with children& families.

www.positiverootsconsultancy.co.uk

07591 165870

UnConditional LoveLOVE DESIGNED TO HEAL

Written Syandene

A few months ago following the end of a 16-hourrecording studio session, the metamorphic sub-ject of ‘Unconditional Love’ sat comfortablyamidst the bold splendour of kick drums, bon-gos and a sound booth - rich with the last tracesof mellifluous tones and semi-quavers reverber-ating ethereally in the air. The neat, ample-sized studio had now taken on a cool,shubeen-type feel with easy laughter, musicalreviewing, and hopes for the future punctuatingthe sessions’ end. It would have been anotherearly morning session closed by jovial goodbye’sand plans for further creative interaction a fewdays down the line, had it not been for the ar-rival of a mutual colleague and chief instigatorwho set the scene for an all-consuming debateon ‘Unconditional Love’. For some reason itseemed an effortless foray into the complexitiesof ‘Unconditional Love’.

None of us, in the stillness of a relaxed Tuesdaymorning studio thought we would knit suchvariant, counteractive, yet unified tones to-gether as the sentimental trajectory of emotivewords bounced off its human targets.

The schools, trains of thought and focus ranthus: (a) - Unconditional love is defined by howmuch you give to another in order to receive thatunconditional love back. (b)- Unconditionallove is designed to create pain and hurt becauseas humans we are susceptible to the well-engi-neered manipulation of our heartstrings to suitanother’s agenda. (c) - There is no such thing as

unconditional love, as it is a man-made portalcreated to give those with an intimate knowl-edge of you, carte blanche to get away with mur-der, and finally; (d) - Unconditional love is thecomposite structure of all the things we are sewnup in, in another and can be broken but neverdestroyed.

Having only broached the subject in a very adhoc way with friends and family, I was surprised(though not shocked) by the myriad of thoughtpatterns emanating from my two colleagues.One could say from looking at the list ofthoughts above, that the sentiments painted apicture of a group of people devoid of any un-derstanding of the true meaning of uncondi-tional love; though as the debate, unravelled, Irealised with my own offering, that we as humanbeings are very much shaped as young adults,initially by our peer groups and social explo-rations with life and spirit. The blueprint to howwe carry ourselves emotionally with regards tounconditional love, imprints itself from ourearthly source; being our parents and then flowsinto our acknowledgement of self in relation toworth which is based in the exploration of loveon many levels, so it would be very easy for meto pull this article together by waxing lyricalabout differing upbringing and how, really,there is only one clear banner of unconditionallove for us all to work from despite our assortedideals of unconditional love, though that wouldbe too easy for the real truth is ,that it is this ob-vious assortment of ideals when it comes to un-conditional love that makes us who and what weare as sentient beings.

When the great Mahatma Ghandi wrote ‘Lovenever claims. It ever gives. Love ever suffers.Never resents. Never revenges itself,’ it is be-cause he had reached a place where the strip-ping bare of ego had enabled him to lovewithout ego unconditionally and this is thefoundation of unconditional love, so it is whenwe have chosen to condition ourselves that the

14

first three points in the schools and trains ofthought above become prevalent as we then be-come slaves to our conditioning though thesefirst three schools of thought are also a tangiblereality for those who have not explored fully thehigher self. From lawyer to non-violent socialprotestor Ghandi used the foundation of uncon-ditional love to transfer everything that he cameto believe about the efficacy of unconditionallove onto a pervading force within his countryand worldwide that sought to impose a delete-rious way of being onto an innocent peopleswho knew anything outside of unconditionalover was/is counterproductive to true harmonyand real love.

There are many of us that will struggle to graspthe embracing of such elevated acts when wehave been hurt or abused in some way by an-other gifted with the act of taking care of ourspirit and heart and in such instances the firstthree points in the schools and trains of thoughtwill ring true for a lot of people. We have all atsome point experienced the pain of pining for alove we no longer have access to when initiallywe believed it was unconditional and so, to lastforever. All experienced the love of a friend orfamily member that chose to sacrifice some-thing of themselves and hold our hands throughthe rain despite being in pain themselves . Allor most of us have been blessed enough to ex-perience the selfless act of a stranger coming toour aid in a moment of distress or sharing wordsof clarity and kindness when we fell into a darkplace within. These selfless acts of uncondi-tional love are really what typify our existenceand it is only when we are collectively tuned intothis type of energy that we can fully understandmahatma Ghandi’s vision.

For it is not about the unconditional love we re-ceive from another that defines our sense ofbeing. It is not about a collective ideal of whatunconditional love should be because we all dif-

15

ferent. Not a completely selfless act because weare all susceptible to imperfection and so engagein this act of the higher self to the best of ourabilities but the unconditional love we chooseto embrace as the norm to give back withoutego, bravado, or a false sense of being, that is thereal act of unconditional love.

Syandene.

DID YOU KNOW�

The number of pyramids in ancient Nubia (aka

Kush & today Sudan) were a total of 223,

(Kerma, Napata, Nuri, Naga, and Meroe), dou-

ble the pyramids of its neighbour Egypt. The

underground graves of the Nubian pyramids

were richly decorated. All pyramids were not

monuments of kings is evidenced by their

great number. Other grandees of the empire,

especially priests of high rank, or such as had

obtained the sacerdotal dignity, might have

found in them their final resting place. The

well-known British writer Basil Davidson de-

scribed Meroe as one of the largest archeolog-

ical sites in the world.