In November 1871 Bismarck rose in the Reichstag and delivered a ...

Bismarck and the German Empire 1871-1918

-

Upload

bjoern-stefan-schmiederer -

Category

Government & Nonprofit

-

view

727 -

download

1

Transcript of Bismarck and the German Empire 1871-1918

-

shanthimFile Attachment20003969coverv05b.jpg

-

Bismarck and the German Empire, 18711918

-

IN THE SAME SERIES General Editors: Eric J.Evans and P.D.King

David Arnold The Age of Discovery 14001600

A.L.Beier The Problem of the Poor in Tudor and Early Stuart England

Martin Blinkhorn Democracy and Civil War in Spain 19311939

Martin Blinkhorn Mussolini and Fascist Italy

Robert M.Bliss Restoration England 16601688

Stephen Constantine Lloyd George

Stephen Constantine Social Conditions in Britain 19181939

Susan Doran Elizabeth I and Religion 15581603

Christopher Durston James I

Eric J.Evans The Great Reform Act of 1832

Eric J.Evans Political Parties in Britain 17831867

Eric J.Evans Sir Robert Peel

Dick Geary Hitler and Nazism

John Gooch The Unification of Italy

Alexander Grant Henry VII

M.J.Heale The American Revolution

Ruth Henig The Origins of the First World War

Ruth Henig The Origins of the Second World War 19331939

Ruth Henig Versailles and After 19191933

P.D.King Charlemagne

Stephen J.Lee Peter the Great

Stephen J.Lee The Thirty Years War

J.M.MacKenzie The Partition of Africa 18801900

Michael Mullett Calvin

Michael Mullett The Counter-Reformation

Michael Mullett James II and English Politics 16781688

Michael Mullett Luther

D.G.Newcombe Henry VIII and the English Reformation

Robert Pearce Attlees Labour Governments 194551

-

Gordon Phillips The Rise of the Labour Party 18931931

John Plowright Regency England

Hans A.Pohlsander Constantine

J.H.Shennan France Before the Revolution

J.H.Shennan International Relations in Europe, 16891789

J.H.Shennan Louis XIV

Margaret Shennan The Rise of Brandenburg-Prussia

David Shotter Augustus Caesar

David Shotter The Fall of the Roman Republic

David Shotter Tiberius Caesar

Keith J.Stringer The Reign of Stephen

John Thorley Athenian Democracy

John K.Walton Disraeli

John K.Walton The Second Reform Act

Michael J.Winstanley Gladstone and the Liberal Party

Michael J.Winstanley Ireland and the Land Question 18001922

Alan Wood The Origins of the Russian Revolution 18611917

Alan Wood Stalin and Stalinism

Austin Woolrych England Without a King 16491660

-

Bismarck and the German Empire, 18711918

Lynn Abrams

London and New York

-

First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to

http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an International Thomson Publishing company

1995 Lynn Abrams

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including

photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Abrams, Lynn. Bismarck and the German Empire, 18711918/ Lynn Abrams. p. cm.(Lancaster pamphlets) Includes bibliographical references. 1. Bismarck, Otto, Frst von, 18151898. 2. StatesmenGermanyBiography. 3.

GermanyPolitics and government18711918. I. Title. II. Series. DD218.A54 1994 943.08092dc.20 9422013

ISBN 0-203-13095-2 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-31003-9 (Adobe e-Reader Format) ISBN 0-415-07781-8 (Print Edition)

-

Contents

Foreword viii

Acknowledgements ix

Glossary and abbreviations x

Chronological table of events xi

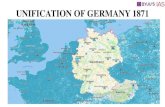

Map: The unification of Germany 186771 xiii

1 Introduction 1 2 The new German state 4 3 Bismarck and consolidation 187190 13 4 Confrontation and integration 18901914 27 5 War and revolution 191418 39 6 Continuities and discontinuities in German history 45

Notes 47

Further reading 48

-

Foreword

Lancaster Pamphlets offer concise and up-to-date accounts of major historical topics, primarily for the help of students preparing for Advanced Level examinations, though they should also be of value to those pursuing introductory courses in universities and other institutions of higher education. Without being all-embracing, their aims are to bring some of the central themes or problems confronting students and teachers into sharper focus than the textbook writer can hope to do; to provide the reader with some of the results of recent research which the textbook may not embody; and to stimulate thought about the whole interpretation of the topic under discussion.

-

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the series editors, Eric Evans and David King, for encouraging me to write this Pamphlet, for their very careful reading of the manuscript, and in particular their willingness to indulge the enthusiasms of a social historian. This Pamphlet is dedicated to my students at Lancaster who have endured, and I hope enjoyed, many hours of German social history. Their enthusiasm, good humour and refreshing insights continue to make imperial Germany a period worth persevering with.

-

Glossary and abbreviations Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine (BDF) Federation of German Womens Associations Bund Deutscher Landwirte Agrarian League Bundesrat Federal Council Burgfriede Civil truce Grossdeutschland Greater Germany Honoratiorenpolitik Politics of notables Junker Prussian landowner Kaiser Emperor Kleindeutschland Lesser Germany Kulturkampf Struggle of civilizations Mittelstand Lower middle classes Reichsfeinde Enemies of the Empire Reichstag Parliament Sammlungspolitik Policy of gathering together Sonderweg Special path Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) German Social Democratic Party Unabhngige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (USPD) Independent German

Social Democratic Party Vormrz Pre-March (pre-1848 revolution) Zollverein Customs Union

-

Chronological table of events 1806 Dissolution of Holy Roman Empire by Napoleon I

1814 Defeat of Napoleon

1815 Congress of Vienna Establishment of German Confederation

1834 Formation of Zollverein (Customs Union)

18489 Revolutions in the German lands and Habsburg Empire

1849 Defeat of liberals, conservative resurgence

1862 Bismarck becomes prime minister of Prussia

1864 Schleswig-Holstein crisis

1866 Austro-Prussian War, defeat of Austria at Kniggrtz

1867 Establishment of North German Confederation

18701 Franco-Prussian War, defeat of France at Sedan

1871 Proclamation of German Empire Bismarck launches Kulturkampf (anti-Catholic legislation)

18739 Economic depression

1873 Three Emperors Alliance (Prussia, Austria, Russia)

1875 Formation of Socialist Workers Party (becomes Social Democratic Party)

1878 Anti-socialist laws

1879 Shift to protectionism Dual Alliance (Germany, Austria)

1881 Social insurance reforms announced

1882 Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria, Italy)

18846 Quest for overseas colonies

1887 Reinsurance Treaty (Germany, Russia)

1888 Accession of Wilhelm II

1890 Fall of Bismarck Lapse of anti-socialist laws Caprivi becomes chancellor

1891 Sunday working abolished

1892 Conservative Party adopts Tivoli Programme

1893 Founding of Pan-German League

1894 Resignation of Caprivi, Hohenlohe becomes chancellor Founding of Federation of German Womens Associations

1898 Founding of Navy League

1900 Blow becomes chancellor Introduction of new Imperial

-

Civil Code

1905 First Moroccan Crisis

1908 Daily Telegraph Affair Reich Law of Association

1909 Resignation of Blow, Bethmann Hollweg becomes chancellor

1911 Second Moroccan Crisis

191213 Balkan wars

1914 (June) Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

(July) Germany offers Austria a blank cheque

(August) Germany declares war on Russia and France, invades Belgium

Britain declares war on Germany Kaiser announces a civil truce (Burgfriede)

1916 Hindenburg and Ludendorff establish military dictatorship

1918 (October) Military hands over power to civilian government, Prince Max von Baden becomes chancellor

(November) Naval mutiny at Wilhelmshaven and Kiel Revolutionary unrest

Abdication of Wilhelm II Scheidemann proclaims a republic

1919 (January) Elections to National Assembly in Weimar

(August) Enactment of Weimar constitution

-

The unification of Germany 186771

-

1 Introduction

The second German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871. More than a century on, having experienced authoritarianism, republicanism, Nazism and division after the Second World War, the two Germaniesthe German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republicunited on 3 October 1990 following a peaceful revolution and the breaching of the Berlin Wall, a symbolic as well as a physical act. In contrast, in the nineteenth century the disparate German lands were unified by blood and iron, a political, diplomatic and military process culminating in Prussias military defeat of Austria in 1866 at Kniggrtz and her victory over France at Sedan in 1870. Prussia thus established her military but also her economic and political supremacy in a small German (kleindeutsch) state under the Prusso-German Kaiser, Wilhelm I, and the Prussian prime minister and German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck.

The new German state rapidly established itself as a leading world industrial and military power. From the mid-nineteenth century Germany experienced rapid industrialization accompanied by urbanization and social upheaval and yet this astonishing social and economic change occurred within a political and constitutional framework that has been labelled pseudo-constitutional, semi-absolutist. The new state, then, was something of a paradox. Germany failed to develop as a modern liberal democracy and thus, it is argued, diverged from the path taken by the other major industrialized states, Britain and France, who had experienced their bourgeois revolutions in 1640 and 1789 respectively. In the words of one nineteenth-century historian, the proud citadel of the new German Empire was built in opposition to the spirit of the age.1

The Empire lasted 47 years. In 1914 Germany embarked upon a disastrous war. Military defeat and exhaustion and disillusionment on the home front precipitated a revolution in 1918. The Kaiser abdicated and the old regime collapsed, to be replaced by the short-lived Weimar Republic. After merely fourteen years of a democratic republican regime, in 1933 Germany witnessed the reassertion of a far worse form of authoritarianism, when the National Socialists led by Adolf Hitler, came to power. They were to subject the German people to twelve years of totalitarian rule and another traumatic and costly war (a topic covered in another Lancaster Pamphlet).2 Defeat was followed by occupation and division. In 1949 Germany was divided into the Communist East and democratic West. It was to be another 41 years before the German people were to be reunited.

Interpretations of the German Empire have been influenced by attempts to explain Germanys more recent troubled past, in particular the origins of the Third Reich. It has been suggested that the roots of Nazism are to be found in the Bismarckian and Wilhelmine era when an authoritarian political system was imposed upon a modernizing economy and society. The dominance of the traditional ruling elites and the apparent failure of the new middle classes to challenge this system supposedly explains Germanys divergence from the models of development taken by other western liberal democracies. So, it is argued, Germany traversed a special path, or Sonderweg. Instead of

-

accommodating the new forces arising from industrialization she tried to deflect them. When this failed and the elites felt their position threatened they began to pursue an aggressive and expansionist foreign policy which culminated in the First World War.3

This view of Germany before 1918 as anachronistic, a dangerous combination of backward and modernizing forces, has dominated interpretations of modern German history in recent years. It has been reinforced by studies of the ways by which the ruling elites retained their power. It is alleged they resorted to repressive and manipulative strategies to maintain their privileges and influence at the expense of the middle and lower classes. This scenario has been graphically described as a puppet-theatre, with Junkers and industrialists pulling the strings, and middle and lower classes dancing jerkily across the stage of history towards the final curtain of the Third Reich.4 However, this is a very simplistic picture. It tends to portray the German people as passive and easily manipulated and the elites as calculating and backward-looking. Historians who have shifted their gaze from party politics and national leaders and have examined the hidden areas of German society such as the everyday lives of the working classes, women, young people, Catholics and Jews, have shown that such repressive and manipulative strategies frequently failed. To return to our puppet theatre, the strings snapped and the puppets took on lives of their own.5

While the study of great statesmen and women has become rather unfashionable in recent years, historians of nineteenth century Germany cannot afford to ignore the role of Bismarck, the most commanding political figure in Germany for almost three decades. Bismarck has been lauded as a hero, a man of action, a truly great statesman, architect of German unification and Prussias and Germanys great power status. Others have cast him in the role of villain, arch-manipulator or puppet master, and the primary cause of Germanys failure to embrace liberalism and democracy before 1918.6 Neither of these polarized approaches does Bismarck justice although Bismarcks own attempts to justify his policies in his memoirs, published in the year of his death, 1898, are not to be relied upon either.

Bismarck once remarked after his fall from power: One cannot possibly make history, although one can always learn from it how one should lead the political life of a great people in accordance with their development and their historical destiny. Yet few historians would agree entirely with this self-assessment. Bismarck was a key player in the making of Germanys history. At the same time, however, having set certain forces in motionin short, having set Germany upon the path of economic modernization and social and political changeBismarck was forced to cling to Gods coat-tails as He marched through world history.7 Far from being the puppet-master, personally responsible for the tensions and difficulties of the Reich, he was instead the Sorcerers Apprentice, a victim of forces which he was at least partially responsible for unleashing. Most historians would now agree that Bismarck bears considerable responsibility for the problems that beset Germany following unification. Both his stylehe could be arrogant, ruthless and a bully at timesand his policies were not in tune with a Germany whose economic maturity was increasingly some way ahead of its political structures. His attempts to govern by exploiting a fragile equilibrium between old and new forces, between the monarchy and parliament, ultimately brought about his downfall. By 1890 he had become an anachronism; he no longer had anything to offer a Germany which had changed immeasurably since he had assumed office.

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 2

-

Wilhelm II, on the other hand, is generally credited with far less personal influence over the course of German history. Indeed, it has been suggested that after Bismarcks fall no-one effectively ruled in Berlin and one contemporary, his uncle Edward VII, described him as the most brilliant failure in history. Wilhelm II certainly does not fall into the category of great statesman. While some historians have suggested that this erratic and complicated Kaiser and his circle of advisers did exert influence on foreign policy, the majority would agree that although Wilhelm II did possess considerable powers of appointment, he contributed little coherent policy to the decision-making process.8

In this Pamphlet I aim to provide an insight into the Germany of Bismarck and Wilhelm II between 1871 and 1918 by drawing on old and new interpretations. Chapter 2 analyses the political, economic and social structures of the new German state in 1871. The main theme of the chapter addresses the paradox of an authoritarian political system superimposed upon an advanced industrial economy and one of the most diverse social structures in Europe, and the problems this presented. Against this background I shall examine the consolidation of the Empire under Bismarck between 1871 and 1890 in Chapter 3. The strategies adopted by Bismarck and the ruling elites to maintain their position of power and influence will be assessed. Following the resignation of Bismarck in 1890 the Germany of Wilhelm II was characterized by confrontation as various interest groups began to mobilize on a collective basis to express their grievances, while at the same time, nationalist sentiment was mobilized behind an increasingly aggressive foreign policy. Chapter 4, then, examines the diversity of Wilhelmine Germany and suggests that the Bismarckian nation state was a temporary or even an illusory entity. Chapter 5 describes the foreign policy conducted by the Kaiser and his chancellors which culminated disastrously in 1914. The experience of the First World War on the fighting and home fronts resulted in revolution in 191819 which ultimately brought about the downfall of the German Empire and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic.

Introduction 3

-

2 The new German state

Before 1866 Germany as a political entity did not exist. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, a loose confederation consisting of 38 states was established. The rulers of the individual states possessed sovereignty over their territories and there was no German head of state or parliament, only the rather ineffective Federal Diet which met at Frankfurt. Prussia and Austria were the largest and most powerful members of the Confederation. During the period 1815 to 1848, known as the Vormrz, Prussia began to consolidate her economic strength aided by the formation of the German Customs Union (Zollverein) while Austria, which chose to remain outside this trading network, continued as the dominant political and cultural force within the Confederation. However, in economic terms, while Prussia was busy building railways and exploiting raw materials, Austria, under the arch-conservative Metternich remained a comparatively backward state.

The revolutions which swept through the German lands in 1848 and 1849 were sparked off by news of revolution in France, but they were fuelled by a combination of social and economic grievance and intellectual activity in the region. Nationalist sentiment was expressed by German liberals during the 1848 revolution. The new Frankfurt Parliament even reached an agreement on the future shape of Germany. It would be a united, federal state with a Kaiser and a parliament elected by universal manhood suffrage. However, national idealism was overtaken by regional practicalities and liberalism was defeated in 1849 by conservative rulers who were unwilling to cede power and a Prussian monarch who refused the crown of a united small Germany (Kleindeutschland).

Nationalism and unification

In 1848 there had been little evidence of popular or grass-roots nationalist sentiment and despite the emergence of nationalist associations and the spread of education, which promoted a greater sense of cultural and linguistic unity, the same was true in 1871 when the German lands were eventually unified. The German question was resolved not by speeches and majority verdicts favoured by the liberals, but by blood and iron as Bismarck had predicted in 1862.

In practice, unification can legitimately be seen as a form of Prussian expansionism. In 1864 Prussia flexed her military and diplomatic muscles over the Schleswig-Holstein question, defeating Denmarks attempt to integrate the two northern duchies and in the process stirring up nationalist passions in Prussia where nationalists had consistently staked a claim to the territories. The Gastein Convention agreed joint Austro-Prussian administration of Schleswig and Holstein but in the longer term Prussia became the

-

dominant power in northern Germany. In the same year Prussia, now the most powerful state in the Confederation, won an economic victory over Austria by securing her continued exclusion from the Customs Union which facilitated free trade among its members. By this date Bismarck was set upon resolving the relationship between Prussia and Austria in Prussias favour before the two states smothered one another in the competition for power and resources. Austria was finally defeated militarily at Kniggrtz in 1866 in a war with Prussia ostensibly fought over Austrias refusal to renounce her independent policy interests in Holstein, but in reality it was Prussias attempt to eliminate Austria from the Confederation. The frontiers of the North German Confederation, forming the core of what was to become the unified German state, were now established (see map).

Having achieved Prussian dominance, however, in 1869 Bismarck admitted that German unity is not at this moment a ripe fruit, while at the same time acknowledging that war was a necessary prerequisite for political unification. In 1870 Bismarcks exploitation of a crisis over the succession to the Spanish throne, resulted in just such a war. Bismarcks promotion of the Hohenzollern candidate for the vacancy in Spain enraged the French who interpreted Bismarcks move as a claim for Prussian dominance in Europe. Following the notorious Ems Telegram incident when Bismarck edited a dispatch reporting a conversation between the Kaiser and the French ambassador to exaggerate the Prussian rebuff of the French, public opinion in France was outraged prompting Napoleon III to declare war on Prussia. The support of the south German states for Prussia in this war guaranteed their eventual affiliation to the North German Confederation and thus their inclusion in a Kleindeutschland (lesser Germany). Following a Prussian victory over France at the Battle of Sedan the German Empire was proclaimed at Versailles on 18 January 1871.

The question of whether Bismarck planned German unification has been much debated by historians. Certainly Bismarck himself denied playing a determining role in the process. In 1869 he wrote: At least I am not so arrogant as to assume that the likes of us are able to make history. My task is to keep an eye on the currents of the latter and steer my ship in them as best I can.9 In fact Bismarck rejected a carefully planned policy since he believed there were too many unknown factors to complicate events. What seems certain is that he recognized that the political and economic ambitions of Prussia could only be realized at the expense of Austria, and moreover, the allegiance of the south German states to a greater Prussia could only be assured by a war fought in a common cause. The war against France, which aroused German nationalist sentiment, fulfilled this condition. Further, it is clear that unification was a means to an end. It allowed Bismarck to maintain political power by appealing to the national idea, particularly after 1866 when he believed the concept of nationalism and German unity possessed the potential to paper over loyalties of a different nature, for example, religious, dynastic or political. The unification of Germany, then, was the result of Bismarcks skilful diplomacy in promoting the interests of Prussia by harnessing national and economic sentiment in favour of a kleindeutsch solution to the German question.

Bismarcks Germany did not assume the true identity of a nation state for several decades. Arguably it was not until 1914, when the German people came together as a nation to defend the fatherland, that a national identity emerged. In spite of being a geographical and political entity and not suffering the same degree of cultural and

The new German state 5

-

linguistic diversity of another new nation state, Italy, Germany remained regionally heterogeneous and the new constitution confirmed the federal nature of the new regime by permitting local rulers to retain control over the internal affairs of their states, including education, justice and local government. The imperial government held responsibility for defence, communications, currency and law codes, although a unified civil code for the Reich was not implemented until 1900. The south and east of the country retained its predominantly rural character while industrialization and urbanization gained a firm foothold in the north and west. Religious and ethnic differences overlaid this regional pattern. Around 60 per cent of the population was Protestant while Catholics, reduced to a minority after the exclusion of Austria, were to be found mainly in the south and the Rhineland. In addition there were minority Poles in Prussias eastern provinces, minority Danes in Schleswig and French in Alsace-Lorraine. There were also ethnic and linguistic Germans left outside the borders of the new state. Germanys social structure was increasingly complex as new groups such as the industrial working class and the bourgeoisie grew in number and importance, while the old, consisting of the peasantry, artisans and landed aristocracy, remained numerically significant and influential.

Political structures

The new state was a Prussified Germany. Prussia was by far the largest state, stretching from the border with Russian Poland in the east to the river Rhine in the west. It was economically powerful, containing the major industrial centres of the Ruhr valley and the Silesian coalfields, as well as thousands of miles of railway track. Despite being the most advanced German state in economic terms, Prussias political structure was amongst the most undemocratic of the German states. Prussian elites ran the states bureaucracy, diplomatic service and armed forces and dominated the Prussian parliament which was elected by a three-class franchise heavily weighted in favour of property owners, thus ensuring the vast majority of propertyless citizens had little say in the running of the Prussian state. With Berlin as the centre of political power Prussias presence was overwhelming. As Michael Hughes has noted, The German Empirerepresented in military reality as well as in political effect the conquest of Germany by Prussia. Prussia dominated the top two layers of the pyramidal political structure established by the new constitution. The king of Prussia automatically filled the post of German Kaiser; the Prussian prime minister became the German chancellor. Prussia dominated the administrative and legislative machinery of the Empire with its representatives outnumbering those of all the other states, duchies and principalities together in the lower chamber of the Bundesrat (Federal Council).

The German Empire was, in theory, a constitutional monarchy, yet in practice it was governed by a Prussian oligarchy. The Reichstag (parliament), whose 400 deputies were elected by universal manhood suffrage in a secret ballot, had little power, and often resembled a talking shop for political parties who were often little more than economic interest groups. All the elected deputies were empowered to do was scrutinize the budget and ratify legislation which could subsequently be vetoed by the Bundesrat. The Reichstag had limited independent power and could be dissolved by the Kaiser on the

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 6

-

recommendation of the chancellor. Neither the government nor the chancellor was answerable to the Reichstag. Most political parties had rather limited social and economic bases and as the German social structure and population distribution altered the Reichstag became increasingly unrepresentative. The Conservatives and Free Conservatives on the right drew support mainly from landed interests but also from some industrialists. The two liberal parties, the National Liberals and the Progressives, represented the professional classes, the bulk of the industrialists and the wealthy middle classes. The emerging working class was represented by the socialist Social Democratic Party. The Catholic Centre Party, founded in 1870, was the most broad-based political grouping which drew support from across the Catholic constituency. Conservative on moral issues it had a progressive edge when it came to campaigning for social reform. The 1871 Reichstag was dominated by National Liberals with 125 seats out of 399, and with the support of the Progressives with 46 seats and the Free Conservatives with 37, they managed to secure a parliamentary majority until 1879.

The government was appointed by the Kaiser. The Kaisers powers were extensive, incorporating control of foreign policy, command of the armed forces and the right to declare war as well as internal martial law. In addition he had the power to appoint and dismiss chancellors and to interpret the constitution. In theory, the chancellor was the Kaisers agent but in practice this relationship was more ambiguous, as we shall see. Under Bismarcks chancellorship the regime has been described, perhaps not entirely accurately, as a plebiscitary dictatorship; after 1890 with Wilhelm II at the helm of a ship served by a series of chancellorsCaprivi, Hohenlohe, Blow and Bethmann Hollwegit has been termed an authoritarian polycracy, meaning dictatorship by a number of different groups. Throughout the life of the Empire, effective political power was held in the hands of a few belonging to the aristocratic elite. In a country undergoing fundamental economic and social change in the second half of the nineteenth century, the effective silencing of the vast majority of the population in the political process was potentially destabilizing. Political liberalism, the ideology of the western European middle classes, appeared to have been defeated in the 184849 revolution and it has been suggested that the bourgeoisie, the traditional standard-bearer of liberal values, was largely acquiescent in the political sphere. Having achieved economic power the industrial middle classes had no need to reform the political system, permitting Bismarck to continue with his reactionary politics. Karl Marx described the German Empire in 1875 as a military despotism cloaked in parliamentary forms. Others have described the constitution as a fig-leaf hiding an authoritarian political system.

1871 did not mark the terminal date of the unification process but merely the start. Unification was largely a political process lacking any deep roots in the German culture. Consequently it took Bismarck another eight years to reshape the state and the parliamentary system and arguably another twelve years after that of attempts to manipulate nationalist sentiment in order to integrate particularist interests into the nation state. The period 1871 to 1873, known as the Grnderzeit (foundation years) saw considerable economic growth stimulated by the currency reform in 1871, but the crash of 1873 signalled the onset of a severe economic recession. Until 1878 Bismarck relied on the support of the National Liberals to carry through his policies consisting of measures to facilitate free trade and economic growth. Steps were also taken to

The new German state 7

-

strengthen central government at the expense of the federal states which had retained considerable jurisdiction over areas such as education, health and policing.

However, Bismarck came under increasing pressure from landowners and industrialists, who were struggling to compete in a free market full of cheap foreign grain and imported manufactured goods, to introduce protective tariffs. In 1879 Bismarck broke free from his dependence on the National Liberals after the 1878 elections which established a Bismarck-friendly coalition consisting of Conservatives, Free Conservatives, the Catholic Centre Party and a section of the National Liberals who supported tariffs. This enabled Bismarck to introduce protectionism and therefore placate the agrarian and industrial interests. Thus began the shift away from liberalism, presaging a period of conservatism which continued throughout the 1880s, indeed 1878 saw the passing of a law to outlaw socialist activities. By 1879 it is not unreasonable to suggest that Bismarcks aims were first to interweave the interests of the various producing classes of Prussia and to satisfy them in the economic field, and secondly, to bind these classes to the monarchical state which was led by him.10

The economy

In the mid-nineteenth century Germanys economy was still predominantly agrarian. In 1852 the majority of the labour force, around 55 per cent, worked on the land and in some areas, like Posen in the east, the figure was closer to 75 per cent. Between 1871 and 1914 the population of Germany increased from 41 million to almost 68 million, and by 1907 industry was the greatest employer, providing work for almost 42 per cent of the labour force. Yet, in 1910 more than half the population continued to live in communities of less than 5,000 people. Compared with Britain, Germany was a late starterher industrial revolution did not get under way until the 1850syet her transformation into a major industrial state was both rapid and remarkable. From 1857 economic growth significantly increased, stimulated by rises in investment, trade and labour productivity, and it was given an extra fillip by unification. A single system of weights and measures, a single currency, and common administrative procedures facilitated greater co-operation and increased trade throughout the German Empire. By the turn of the century Germany was challenging the first industrial nation, Britain, for economic dominance in Europe. But it is the combination of agrarian revolution, industrial take-off and political change that concerns us here, and in particular the reactions of traditional and new social classes to this economic revolution.

Many social commentators regarded the rural Germany of the early nineteenth century as a bulwark against revolution. They idealized agrarian society and praised its way of life centred upon the household economy, the church, and traditional practices. Urban society, on the other hand, was regarded as alienating and a breeding ground for irreligiosity and immorality. But rural society was not static and not at all idyllic.

Following the agrarian reforms removing feudal bonds in the late eighteenth century and legal reforms of the early nineteenth, the agrarian sector almost doubled its productivity between 1840 and 1880, stimulated by transport improvements, regional specialization and technical innovation. More land was brought under cultivation and more attention was paid to commercial crops such as potatoes and sugar-beet. The estate-

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 8

-

owning aristocracy, particularly the Prussian Junkers east of the river Elbe, profited from the agrarian revolution. Until 1861 their land was exempt from taxation and these aristocrats retained their influence at the top levels of the bureaucracy, the military and the diplomatic service.

Rural society was profoundly altered by legal and technical advances. Farmers were obliged to produce goods for the market in order to survive which required the intensification of production and contact with outsiders. Goods were taken to market in nearby towns, and rural inhabitants for whom no local work was available would migrate to nearby villages and towns in search of work. Young women, in particular, were often sent away to be household servants. The peasantry was not as backward and ignorant as many portrayed them. They maintained customs and superstitions only as long as they were deemed functional. Until the discovery and use of medical cures and remedies for example, rituals, such as exhuming and decapitating the body of the first victim of an epidemic to prevent further deaths, were common. With the introduction of artificial fertilizers and the spread of education, the vagaries of the weather, the causes of poor harvests and illnesses were better understood. In these circumstances, including the introduction of universal manhood suffrage, the politicization of the peasantry was inevitable. Peasant insurrection had contributed to the 1848 revolutions. By the 1890s peasant grievances were being articulated by pressure groups and political parties.

We should not be sanguine about the fortunes of the small farmers and peasants in this period. The peak of the landowners power coincided with increasing uncertainty for wage-earning labourers who were affected by agricultural reorganization. As wages rose almost everywhere from around 1850, farmers began to invest in machinery enabling them to lay off farm workers and hire seasonal labourers when necessary. Subsistence farmers found survival increasingly difficult. The result was a widespread flight from the land. Between 1850 and 1870 around two million people left Germany for overseas, mainly for the United States, while the vast majority of landless labourers found work in the new industrial centres.

It was this internal migration that created Germanys industrial society. Districts which had been predominantly rural urbanized rapidly. Towns and cities grew at a phenomenal rate fuelled by migration from the countryside as opposed to a rising birth rate. For example, Bochum, a village in the Ruhr valley with a population of only 2,000 in 1800, grew so rapidly that by 1871 over 21,000 people had made the town their home, rising to over 65,000 by 1900. In cities the population explosion was even more marked. Hamburgs population grew from almost 265,000 in 1875 to close to one million in 1910, an increase of some 250 per cent. The number of cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants increased from 271 in 1875 to 576 in 1910.

Until the 1860s artisans outnumbered factory workers in most towns but German industrialization was founded on heavy industrys exploitation of raw materialscoal, iron and steel and engineering were the leading sectorsso that by 1882 workers in industry constituted almost 40 per cent of the workforce. The construction of railways acted as a catalyst for the development of other industries. The Ruhr valley was the powerhouse of German industrialization, where towns like Essen, Bochum, Dortmund and Duisburg, surrounded by pits and steelworks, attracted a huge labour force, but other regions such as Upper Silesia and the Saar coalfields and cities like Leipzig, Chemnitz, Hamburg and Dsseldorf, also contributed to the prolific growth rate. Gradually, large

The new German state 9

-

scale enterprises took precedence over small workshops. By 1907 around three-quarters of industrial workers were employed in enterprises with more than fifty employees.

Germany was privileged by her possession of abundant raw materials and the ability to exploit technology already tried and tested in Britain and Belgium. But the mode of financing German industry, the advantageous trading conditions and the expansion of the education system were equally important. Economic development was, to a large degree, financed by the state via the large banks. Prussias membership of the Zollverein also contributed to the early years of growth as this system of tariff protection against foreign competition and maintenance of low internal tariffs stimulated trade in the long term. Prussia was also fortunate in possessing territories containing essential natural deposits and resources enabling her to establish early dominance over Austria. Finally, Germany placed great faith in the value of education. Compulsory elementary education had been introduced in Prussia in 1812, technical institutes were opened in the 1820s and a network of vocational schools was soon set up to train workers for industry.

After a period of almost continuous economic growth the German economy hit the buffers in 1873 with the onset of the Great Depression. Between 1878 and 1895 growth was more uneven until recovery between 1895 and 1913. This second wave of growth was aided by state intervention and the development of new sectors like chemicals and electronics. The Depression, which did not recede until 1879, had profound consequences. The period beginning in 1873 saw the organization of economic interest groups, nationalism of a rather chauvinistic nature, militarism and modern anti-semitism. The Depression caused the landed and industrial interests to mobilize behind the policy of protective tariffs in order to retain their economic and political base. Thus, they succeeded in maintaining their power and the political status quo.

In the first two decades of the Empire, Germany had been transformed from a mainly agrarian to a predominantly industrial state. Yet this had been achieved under a political system which had not adapted to the demands of a modern industrial economy. When the economy faltered the reaction of the political system was to shore up the ruling elites by giving in to their demands for protection.

Society

Germanys transformation into a modern industrial economy was accompanied by major changes in her social structure. The most striking development was the rise of two new classesthe industrial bourgeoisie and the proletariatbut traditional social strata also found themselves forced to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. The landowning aristocracy, far from dwindling in size and influence, consolidated and even strengthened its economic and political position with the help of the state. Once feudal ties had been dissolved, many landed aristocrats expanded their landholdings at the expense of peasant farmers. Some of them diversified and made fortunes from sugar-beet production and distillation of potato schnapps, forming a new agrarian entrepreneurial elite.

Another traditional group did less well. Shopkeepers, artisans and small businessmen, collectively known as the Mittelstand (lower middle classes), initially benefited from industrialization as the market for their products and services increased. Yet increased competition from larger concerns producing manufactured goods and the appearance of

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 10

-

early department stores threatened to push this middle stratum down into the mass of the wage-earning proletariat, destroying their fragile independence. The Mittelstand regarded itself as the backbone of a stable society but its members found themselves squeezed between big capital and the industrial proletariat, unable to compete with the one but always in danger of falling into the latter.

The 1850s and 1860s witnessed the emergence of the industrial entrepreneur, the successful businessman who invested in and profited from the new industries. Men like Alfred Krupp represented the pinnacle of this industrial elite. Its members began to extend their influence in economic and cultural spheres, dominating local Chambers of Commerce and municipal councils. Some of them were almost like feudal landlords. Krupp, for instance, whose steelworks dominated the town of Essen, acted like the owner of a landed estate, playing the generous paternal employer by providing workers with carrots in the form of housing and recreational facilities while simultaneously wielding a stick against those who tried to join trade unions or the Social Democratic Party. Krupp and his family moved out of the smoky, dirty town to an ostentatious villa set in magnificent parkland, emulating the lifestyle of a landed aristocrat.

Yet, surprisingly, these businessmen generally failed to exert political influence on the national stage once the prime aim of protective tariffs had been achieved. From the end of the 1870s these industrialists gradually abandoned the ideal of liberal competition and shifted towards what has been termed organized capitalism, one of the manifestations being the formation of cartelssyndicates of businessesin order to protect themselves from the uncertainties of the market. Neither, as we have seen, were many of these businessmen especially liberal-minded in their factory management strategies with factories not infrequently run on authoritarian lines.

The other new class created by industrialization was the industrial proletariat. This was an extremely heterogeneous labour force. Long-standing town dwellers mixed with migrants from the rural hinterland; native Germans rubbed shoulders with Polish migrants; Protestants and Catholics worked side by side down the mine or on the factory floor; skilled and unskilled, former peasants and artisans, men and women, provided the muscle-power behind Germanys industrial growth. Many took time to adapt to their new surroundings and maintained contact with their native villages, returning frequently and upholding traditions like absenting themselves from work on Monday (known as Saint Monday) after a weekend of drinking. Co-operation amongst workers was inhibited by residential segregation of particular groups, especially Poles and miners, and the high mobility rates of young male workers who moved from town to town, company to company, in search of higher wages. The new working class was fragmented. There was more to divide it than to unite it.

The living and working conditions of the vast majority of workers were extremely poor in these early years. Housing and public amenities had not kept up with the population influx so that single male workers were frequently housed in barracks or they became lodgers, sharing the same makeshift bed with a colleague on a different shift. Almost one-third of all working-class households in 1914 had one or more lodgers. Forty per cent of workers in Hamburg inhabited just one heated room in 1875. Towns were unhygienic; sanitation was often primitive. In Hamburg the failure to provide clean drinking water was responsible for the loss of around 9,000 lives in the 1892 cholera epidemic, the majority of victims coming from the lower classes. The infant mortality

The new German state 11

-

rate remained high at 210 deaths per 1,000 legitimate live births and did not fall significantly until after the turn of the century.

Working conditions were little better. In the 1870s workers typically laboured a twelve-hour day, six days a week and many endured a long journey to and from work too. Overtime could be demanded at short notice and it was not uncommon for miners to work one eight-hour shift immediately after another. Accident rates were high, especially in the mines and on construction sites. Although real wages had risen steadily before 1873 and workers were able to change jobs to take advantage of better conditions, during the Depression conditions worsened and workers began to suffer unemployment and falling real wages, at least until 1895. For many families meat was a luxury and potatoes and bread formed the staple food items. It was not until the 1890s and 1900s that workers capitalized on their collective experience and began to overcome their differences in order to challenge the power of the employers by joining trade unions and engaging in collective action in order to improve pay and working conditions.

Conclusions

By the time she was unified Germany was already on the road to becoming a major industrial power. Bismarck inherited a state that was already in the process of economic and social transformation. These changes were accelerated by political unification, but no attempt was made to adapt political structures to economic and social realities. By 1914 a dramatic transformation had altered the face of the new nation state so that the land-based population had fallen to around 40 per cent and over 20 per cent lived in cities of more than 100,000 inhabitants. And yet this state of Bismarck and Wilhelm II was ill-equipped to establish a comfortable relationship with the new social classes. Political power remained in the hands of the traditional conservative elite despite the transfer of economic power to the industrial bourgeoisie. In an attempt to consolidate this diverse and inherently unstable state Bismarck and his government embarked upon a series of ruling strategies which, instead of opening up the political system to represent those upon whose backs the state was being built, succeeded in cementing in place the structures of power more suited to a previous age.

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 12

-

3 Bismarck and consolidation 187190

Otto von Bismarck was appointed prime minister of Prussia in September 1862. He was born on All Fools Day in 1815, the son of a Prussian Junker and a mother from a successful family of civil servants. Bismarck was well educated in Berlin, a city he was said to hate, and after university in Gttingen he embarked upon a career as a civil servant. When he was still only 24 years old he resigned his post and returned home to the family estate in Pomerania but boredom soon found him engaging in Prussian politics. From 1851, in his position as Prussian representative to the Federal Diet of the Confederation in Frankfurt, he fought to maintain Prussian supremacy in the face of the Austrian challenge in the 1850s. In 1859 he was moved to a new diplomatic posting in St Petersburg but he continued to champion the cause of Prussia within the Confederation. Until 1860, as a diplomat Bismarck had been at the margins of power, but a constitutional crisis in Prussia, which saw open conflict between the sovereign and the parliament over the issue of the reorganization of the army, resulted in the recall of Bismarck from his posting in Paris to head a new cabinet. Between 1862 and 1866 Bismarck ruled Prussia unconstitutionally, ignoring the parliament, illegally raising the necessary finance by taxation and pushing through the army reforms. In his new position as prime minister of Prussia Bismarck sought to enhance the position of Prussia at every available opportunity. Just nine years later he had achieved his aim of securing Prussias position within Germany and setting her on the path of economic success and political dominance.

It has been said of Bismarck that he protested too much and argued too much, ate too much and paraded too much, but it is undeniable that he was a skilful manipulator, a successful diplomat and something of a pragmatist. Upon his appointment as Prussian prime minister one liberal critic labelled him an adventurer and predicted his occupancy of office would be short. On domestic policy he was seen as a reactionary, an enemy of liberalism and not afraid of violating the constitution. Another critic predicted the rule of the sword at home and war abroad. There was some truth in this prediction as we have already seen. But after 1871, and particularly after 1878, as chancellor of the German Empire, his policies, particularly at home, appeared increasingly out of step with social and economic reality. Having unleashed new social forces, Bismarcks system could be described as crisis management in an attempt to contain the middle, but also the lower classes. In alliance with the ruling elites, it has been suggested he attempted to consolidate the new German state by means of repressive and manipulative ruling strategies. So-called enemies of the Reich (Reichsfeinde) were suppressed, the German people were subjected to a regime of indoctrination, and attempts were made to manipulate nationalist sentiment in order to deflect political challenges and tie citizens to the benevolent state. As a consequence of the emasculation of opposition politics and grass-roots dissent, Germany under Bismarck and increasingly under Wilhelm II, developed into a society of competing interest groups, manipulated from above while

-

tensions gathered beneath the surface. By means of what is known as a Bonapartist ruling strategymeaning a combination of repression of opponents, plebiscitary elections, concessions to progressive, liberal demands and diversion of domestic pressures into foreign adventuresthe German elites managed to resist challenges to their privileged position and indeed, maintained their power and influence until the 1918 revolution, having entered the First World War as a last-ditch attempt to deflect increasing social tensions and dislocations which threatened the political status quo. Such an interpretation of the period 1871 to 1890 places Bismarck centre stage as archvillain, manipulator extraordinaire, master of Realpolitik (the pursuit of self-interest in the absence of ideology) and the architect of authoritarian rule. However, one could also interpret such strategies more charitably, as pragmatic attempts by Bismarck and the elites to deal with the forces unleashed by industrialization and unification using the only tools they had at their disposal.

Bismarckian ruling strategies

The heterogeneity of the German Empire was a thorn in Bismarcks side. Some of its constituent elementsnamely Catholics, ethnic minorities, Jews and socialistswere identified as less than enthusiastic supporters of the nation state. Although these minorities never posed a serious threat to the state, Bismarck chose to label them Reichsfeinde and subjected them to policies ranging from discrimination to outright repression.

Enemies of the Reich

Catholics were the first group to be labelled and subjected to repressive policies. After 1866 Catholics were a minority in Germany. Constituting almost 40 per cent of the population they were concentrated in predominantly rural areas in the south-west and the Rhineland. Dubbed enemies of the Reich on account of their allegiance to Rome, and regarded by liberals as backward-looking and superstitious, a brake on Germanys development, they were seemingly ideal candidates for a discriminatory and coercive policy. In 1870 the first Vatican Council issued the doctrine of Papal Infallibility and in its wake, fearing the threat posed by clerical politics, Bismarck launched what is known as the Kulturkampf, literally a struggle of civilizations, but effectively a programme of discrimination against the Catholic Church. In 1871 the Reichstag passed the pulpit paragraph which prevented the misuse of the pulpit for political purposes. A series of Prussian measures followed which removed Catholic influence from the administration and inspection of schools. Then, in 18723 the Reichstag passed a series of far-reaching laws known as the May Laws or Falk Laws after their architect, the Prussian Minister of Culture. Adalbert Falk was motivated by his unshakeable belief in the complete separation of church and state. Hence, the Catholic section of the Prussian Ministry of Culture was abolished, Jesuits were expelled from German territory and the Catholic Church was subjected to considerable state regulation. The political voice of Catholics, the Centre Party, was also attacked on the grounds that the mere existence of a denominational party implied its opposition to the state although Bismarcks accusation

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 14

-

that the Centre was a rallying focus for elements hostile to the Prussian state and the Empire perhaps provides greater insight into his motivation for attacking the party. In 1874 the articles of the Prussian constitution guaranteeing religious freedom were repealed, priests could be expelled if they violated the May Laws, the 1875 bread-basket law denied state subsidies to any priest who refused to sign a declaration in support of government legislation, and finally, in 1876, civil marriage was made compulsory.

The Kulturkampf was seemingly motivated by two issues. The nation Bismarck was trying to consolidate was founded upon Protestant Prussia. The Catholic Church was regarded as a dangerous independent authority, capable of mobilizing the Catholic population against the state and of stirring up nationalist passions amongst Polish Catholics on Germanys eastern border. Second, the Kulturkampf had a pragmatic political dimension. Bismarck was reliant upon the National Liberal Party for support in the Reichstag. Despite classic liberal principles such as freedom of the individual the liberals supported the Kulturkampf by arguing that the regressive influence of the Catholic Church had to be dismantled if the German people were to be emancipated as individuals. For liberals, Catholic schools, seminaries and even charities were symbols of closed minds and backwardness. Thus, the campaign can be interpreted as a means employed by Bismarck of securing National Liberal support for the government while simultaneously appeasing liberal demands for greater parliamentary democracy.

The Kulturkampf failed on both counts. In the short term Catholics were alienated still further from the German state. Ordinary lay Catholics demonstrated their hostility to the regime by refusing to celebrate national holidays like Sedan Day which usually took the form of patriotic displays of military pomp and ceremony. In strong Catholic areas like the Rhineland there were demonstrations involving thousands of people, public meetings and attacks on state officials. So-called passive resistance was widespread: flying the papal flag, providing sanctuary to priests on the run. Most states lacked the administrative apparatus to enforce the repressive measures. In the longer term the Kulturkampf forced the Catholic community to look to itself for a sense of identity in a hostile Protestant state. An identifiable Catholic sub-culture emerged consisting of social groups, welfare organizations, trade unions, leisure associations and, of course, the Catholic Centre Party. Until 1890 the Centre retained the allegiance of around 80 per cent of Catholic voters and was the largest party in the Reichstag with around 100 seats. The rise of Centre Party strength subsequently forced Bismarck to abandon the Liberals. This also coincided with his abandonment of another tenet of liberal principlefree tradeand may be seen as the beginning of a more conservative era, signalled by liberal electoral decline.

By 1878 it was clear the anti-Catholic campaign had failed. In 1879 Falk resigned and the same year Bismarck switched to a protectionist policy with the support of the Catholic Centre Party. Indeed, the Centre seemed to replace the National Liberals as the party of government. Many of the anti-Catholic measures were repealed between 1879 and 1882 but the campaign had rendered serious long-term damage to relations between the state and the Catholic Church.

Poles, Danes, citizens of Alsace-Lorraine and Jews were also labelled Reichsfeinde. Poles constituted a significant minority in eastern Prussia and Bismarck systematically attempted to undermine them and Germanize them. In 1886 a Settlement Law encouraged the movement of German peasants into the eastern provinces, thus delimiting

Bismarck and consolidation 1871-90 15

-

the power of the Polish aristocracy. Moreover, a series of language laws made German the official language. There were also thousands of Poles living in industrial centres who had been recruited by desperate mine-owners in a period of labour shortage. Despite the fact that they were contributing to Germanys economic growth they were victimized for their continued espousal of Polish nationalism and were forbidden to use the Polish language. Nevertheless, Poles continued to form their own clubs, publish Polish newspapers, worship as Polish Catholics and they even formed their own political party.

Just as Poles were regarded as enemies of the Empire on account of their allegiance to Polish nationalism and Catholic-ism, so inhabitants of Alsace-Lorraine, a territory ceded to Germany by France after the Franco-Prussian war, were suspected of harbouring dangerous sentiments for the French motherland. Here too, German was made the official language of instruction in 1873. Similarly, language laws and expulsions were used against the Danes of Schleswig-Holstein.

Jews, although formally emancipated throughout the German lands in the early nineteenth century, were intermittently subjected to anti-semitic attacks and discrimination. For instance, after the 1873 economic crash prominent Jews in finance and business became targets of resentment. Between 1873 and 1890 there were around 500 publications on the Jewish question expressing anti-semitic sentiment. In Berlin especially, where there was a well-established and sizeable Jewish community, Jews were targets of anti-semitic street gangs and their properties were damaged. The Jew was treated as a scapegoat for Germanys economic and spiritual ills. In the 1880s anti-semitism became more organized with the formation of anti-semitic political parties like the Christian-Social Party led by Adolf Stcker who was elected to the Reichstag in 1881, and the German Social Reform Party, although single-issue parties were never very successful at the polls. Of course anti-semitism was never official government policy but these organizations received tacit support from the highest levels. Although several of those closest to Bismarck were Jews, his banker and doctor for instance, he never publicly opposed anti-semitism and indeed, on occasions he sanctioned blatant anti-semitic acts like the expulsion of 30,000 from eastern Prussia in 1885, of whom a third were Jewish. Bismarcks son Hubert was openly anti-semitic. Moreover, the Conservative Party became an outspoken adherent of anti-semitism. In 1892 it adopted the Tivoli Programme which officially incorporated anti-semitism into the Party programme, thereby tacitly sanctioning discriminatory policies against Jews.

It was the Social Democrats who bore the full brunt of Bismarcks repressive policy. Social Democracy had been slowly making progress amongst the industrial working class during the 1860s and 1870s. In 1875 a Socialist Workers Party was formed from an amalgamation of Lassalles Workers Association and the Eisenach Party of August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht. Standing for equality and democracyvalues sadly lacking in Bismarcks Germanythe socialists were a potential threat to a system based on patronage and privilege. Although they secured a mere twelve seats in the 1877 Reichstag elections, at the grassroots level trade unionism was gaining strength. Membership of the socialist Free Trade Unions numbered 50,000 in 1877.

Bismarck was provided with the opportunity to clamp down on Social Democratic activity in 1878 following two attempts on the life of Wilhelm I. The first involved a plumber who fired two shots at the Kaisers carriage, harming no-one. On the second occasion, however, Dr Karl Nobiling fired at the Kaiser and wounded him quite severely.

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 16

-

Neither attempt had anything to do with the socialists but Bismarck had been looking for a chance to kill two birds with one stone: damage the Social Democrats and simultaneously weaken the Liberals. Bismarck undoubtedly wanted to vanquish the socialist presence in Germany but at the same time anti-socialist measures introduced in 1878, following the dissolution of the Reichstag and a swing to the right in elections, were designed to weaken liberal opposition.

In the event Bismarck partially succeeded in the second of his aims as some liberals supported him while others voted against the anti-socialist legislation thus splitting the largest party. The Anti-Socialist Law introduced in June 1878 and which remained in force for twelve years, had a similar effect on the labour movement as the Kulturkampf had on the Catholic community. The legislation did not outlaw the socialists altogether. The Socialist Workers Party was permitted to fight elections and its deputies were allowed to take their seats in the Reichstag, but all other extra-parliamentary activity was strictly suppressed. Socialist agitators were arrested, imprisoned and could be expelled, socialist clubs were forced to dissolve (although many maintained an underground existence), socialist newspapers were banned and the Party was forbidden to collect financial contributions.

Despite constant harassment and vilification the Party gained in strength throughout the 1880s as the economic situation worsened and the industrial working class gained in confidence, partly aided by the re-emergence of trade unions. Workers continued to vote socialist in defiance so that by 1890 when the law was not renewed the Party, now renamed the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) had 35 Reichstag deputies and almost 20 per cent of the popular vote. By 1914 it had more than one million members and was the largest parliamentary party with 110 deputies out of 397. Bismarcks policy had failed to weaken socialism; in fact the movement emerged from twelve years of repression stronger and more resolute.

Parliamentary representation did little to overcome the hostility and discrimination faced by ordinary socialist men and women in their everyday lives. In order to try to combat this, the SPD embarked upon the task of building a socialist subculture consisting of a cradle-to-grave network of subsidiary social clubs, sporting facilities, educational institutes and co-operative organizations. Many workers and their families were thus provided with a support network which lessened their feelings of alienation from a hostile state which had attempted to destroy their political representatives.

The Bismarckian strategy of repression of enemy groups was arguably effective in the short term in that those affected were forced to retrench while Bismarck scored important political points and secured his political position. But Catholics, socialists and minority groups were not reconciled to the Bismarckian state and emerged from their repression stronger and better organized. However, they still had to struggle against a more pervasive and subtle attempt to consolidate and legitimate the new German state.

Ideological conformity

The policy of repression targeted specific enemy groups. The imparting of a nationalist, monarchist and conservative ideology via the Protestant (or evangelical) Church, the education system and the army, was more insidious in everyday life. The values instilled

Bismarck and consolidation 1871-90 17

-

by these institutions were designed to perpetuate the social structure and the hierarchy of power in German society.

Under the Holy Roman Empire each individual ruler was free to determine the official religion of the state. The state thus exerted considerable influence over the church and this situation continued until 1918 in Protestant areas of the German Empire. After 1871 the Kaiser was the head of the Protestant Church and in turn the church recognized the legitimacy of the state and used its influence via the pulpit and the classroom to ensure the compliance of the German people, instilling into them the values of obedience, discipline and orderliness. Through the sermon and religious instruction the legitimacy of the Kaiser was reinforced. The Protestant Church undoubtedly preached allegiance to the German state and it upheld the conservative hierarchy, reinforcing the authoritarian role of the father within the family, the employer in the factory and the Kaiser in the nation. The relative absence of dissenting Protestant religious sects (in contrast with Britain) meant there was no alternative religious identity for those Protestants who rejected the covert alliance between church and state.

However, the Protestant Church was losing some of its authority owing to falling membership and declining church attendance. In urban areas the Protestant clergy soon became alienated from the labouring population on a day-to-day basis. Church building did not keep up with the population increase in working-class areas and church attendance on Sunday declined, especially amongst men who needed one day to recover from the exertions of the working week. Only 8 per cent of Hamburg Protestants took Communion in 19068 and while the church was still used for major life-cycle ritualsbaptisms, marriages, burialsmany workers reported they no longer believed in God. The German Protestant Church increasingly became the preserve of the bourgeoisie who publicly ascribed to the values of decency and hard work propounded by rather puritanical pastors. The Catholic Church, on the other hand, had traditionally appointed local priests and had maintained contact with the new generation of industrial workers by means of its social and welfare network. Secularization rates were consequently lower in Catholic areas.

One might have expected the Catholic church to have adopted a more confrontational stance towards the German state after the discrimination of the Kulturkampf but in many respects the Catholic Church and its subsidiary organizations may have helped to maintain the stability of the Empire by aiding the integration of Catholics into the state. On the whole Catholicism in Germany did not challenge the values propagated by the state even though it adopted a strong stance on the family and education. What has been called the Catholic milieu, including welfare and reform associations, womens and youth groups, and even trade unions, tended to provide Catholics with a home in a hostile Protestant state.

Despite rising secularization both churches continued to exert a powerful influence on German society, in the community via schools, hospitals and social clubs, in the workplace via the Christian trade unions, with 350,000 members by 1912, and in political life through the nominally Protestant National Liberals and the Catholic Centre Party, which lent an air of legitimacy to the status quo.

The German education system was relatively advanced compared with the rest of Europe. Most states had passed laws requiring attendance at elementary school at the beginning of the nineteenth century. In 1871 there were more than 33,000 primary

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 18

-

schools (Volksschulen) in Prussia educating almost four million children. By 1911 these figures had increased to almost 39,000 and 6.5 million. As a consequence literacy rates were very high. By the end of the nineteenth century fewer than five Germans in one thousand were unable to read and write.

During the Kulturkampf religious influence over education was severely curtailed but Protestant values continued to have an impact on the formal and informal curriculum. With a formidable number of schools the education system was in a prime position in 1871 to take on the task of encouraging a sense of nationalism amongst Germans who were still divided by regional, community, ethnic and religious loyalties. Values such as loyalty to the monarchy, obedience to the state, discipline and hard work were instilled in pupils. Schools were instrumental in the so-called Germanization of non-Germans through the teaching of the German language, culture and history. History was given particular significance. Experience shows, wrote one primary school teacher, that the child must be acquainted with the history of the Fatherland and with the lives of men known to the Volk. Schoolchildren regularly celebrated national victories and state occasions, participating in flag-waving and street processions, and nationalist and monarchist propaganda was disseminated through text books. Pupils read that their Kaiser was a man of true pietywith an unshakeable belief in God and were encouraged to emulate him. At the same time, socialist ideas were also actively discouraged. Wilhelm II was especially keen to use the education system for this purpose and an education bill put forward in 1890 explicitly stated that its main purpose was to strengthen the state in its battle against the forces of revolution.

The education system did not greatly promote social mobility. Rather, it functioned to keep every citizen in his or her place. Few were encouraged to continue their schooling at secondary level and only those who had the financial resources could afford to do so. Some did benefit from an advanced technical education which created a pool of skilled labour. The system as a whole perpetuated the power of the traditional elites. Only wealthy and well-connected young men progressed to grammar school and university. Fewer than one in a thousand university students in 1890 were sons of workers. Women were not admitted to the universities until the 1900s. Once admitted to higher education, students were rarely encouraged to adopt a critical perspective. They were trained to reproduce the views of the political and professional elite, and conformity amongst the student body was reinforced by student fraternities who perpetuated aristocratic codes of honour, including the duel. Therefore, the bourgeoisie, instead of challenging the existing system accommodated themselves to it, a process which has been termed the feudalization of the bourgeoisie.

Military victory had sealed the unification of Germany and henceforward the military possessed considerable prestige, power and a good deal of popularity. The army was responsible to the Kaiser alone. Article 63 of the constitution stated that the Kaiser determines the peacetime strength, the structure and the distribution of the army. Following military reorganization in 1883 the army strengthened its independence and neither the chancellor nor the Reichstag could limit its power.

It has often been said that imperial Germany was an excessively militarized society. The size of the army more than doubled from approximately 400,000 men in 1870 to 864,000 in 1913. Conscription ensured that all men had two to three years of experience of army life during which time they were imbued with a sense of national consciousness

Bismarck and consolidation 1871-90 19

-

as well as discipline and ideological conformity. It was the unstated function of the army not merely to defend Germany against external aggressors but to preserve the internal status quo against alleged enemies like the socialists. To this end major efforts were made to prevent Social Democrats from infiltrating the ranks. Army recruits were not permitted to be members of the SPD and they were indoctrinated with patriotic notions.

There is little evidence to suggest these measures worked, but former members of the armed forces were recruited into the police force, lending that organization a distinctly militaristic character, and upon leaving the army many Germans joined a local ex-servicemens association which enthusiastically participated in public ceremonial engineered by the state. Local shooting associations too regularly held festivals incorporating military-style ceremonies, much marching, wearing of uniforms and firing of cannon.

Along with the education system, the army, and particularly the Prussian officer corps, served to perpetuate the existing system. In 1860, 65 per cent of officers in the Prussian army were from aristocratic families. Although this proportion did decline to around 30 per cent by 1913, aristocrats were still overrepresented in the highest ranks. In fact the General Staff became even more aristocratic. Men from the middle class were accepted into the prestigious officer corpsa necessity when many sons of the aristocracy were following more lucrative careers in industrybut their background was subject to detailed scrutiny beforehand. Middle-class officers were not accepted as equals and in Prussia were derisively called Compromise Joes. Once a man was accepted into the system of privilege and honour he was unlikely to challenge the power base of the military elite.

In view of the background of those recruited, it is not surprising that the officer corps was an excessively conservative institution. It jealously protected its code of honour which included the right to defend that honour in a duel, and consciously demarcated itself as a special caste. Under Wilhelm II this conservatism was manifested in the officer corps determination to assert Germanys position in the world, thus supporting the aggressive and expansionist foreign policy of the Kaiser and his chancellors, coupled with a willingness to defend the state from the so-called enemy within.

Social reform and social imperialism

A combination of manipulation and diversion may be identified as the third strategy in the attempt to produce a collective loyalty to the German state. The ruling elite adopted the strategy of the carrot and the stick: an attempt to suppress the unsettling and allegedly dangerous forces in German society and to indoctrinate all Germans with the ideology of the conservative elites was combined with a counter-tactic of social reform and social imperialism to head off the possibility of revolution and convince the workers of the states benevolence.

Bismarck is reported to have said, the citizen who has a pension for his old age is much more content and easier to deal with than one who has no prospect of any. When Bismarck introduced social reform legislation in the early 1880s, it was not his sole intention genuinely to improve the working and living conditions of the workers. Rather, he was additionally concerned to maintain the stability of the system, and head off the threat of unrest, by showing that the state could offer more to the workers than the Social

Bismarck and the german empire, 1871-1918 20

-