Beyond the monuments: a living heritage; UNESCO sources; Vol.:80 ...

-

Upload

phungnguyet -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

3

Transcript of Beyond the monuments: a living heritage; UNESCO sources; Vol.:80 ...

Beginning with this issue,UNESCO Sources

is available on

Internet

under the heading:publications

at our address:http://www.unesco. org

instead of only focusing on whose fault itis that the continent has almost found it-self relegated to the dustbin of interna-tional interest. Africa must learn how togradually cast off its chains of dependency.I will at this point leave you withDostoevsky’s axiom: “Man holds the rem-edy in his own hands...”

Alphonsou A. Yarjah maintains that above all Africa’sunderdevelopment ensues from the dictatorships im-posed by its leaders. This position is somewhat doubt-ful with so many countries outside the continent expe-riencing extraordinary economic growth despite theirauthoritarian regimes.Most importantly, Africa is now undergoing an acceler-ated process of democratization, signs of which, amongothers, are seen with the flourishing number of inde-pendent press and radio stations, which Sources regu-larly reports on. Ed.

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

2 . . . . . .

✉✉✉✍

THE CHAINSOF DEPENDENCYAlphonsou A. YarjahLibrarianSt. Petersburg (Russia).

Dossier No. 75 deservesa special place in your archives for describ-ing in graphic details the glaring advan-tages and disadvantages the new informa-tion technologies are going to have on so-ciety while also suggesting means of curb-ing the polarizing effect of the presagedglobal village. Moma Aly Nidaye’s articleon “The Race Against Marginalization”drew my attention the most. While this ar-ticle is not devoid of useful suggestions, itdeserves commenting. His argument thatthe political will to invest is ‘beginning totake shape’ is at best hypocritical, and atworst misleading. While a few projects areworth mentioning, such isolated examplesare not enough to advance the conclusionthat many African countries are incontest-ably ready for any meaningful change onthe continent.

It is no secret that today most of Afri-ca’s leaders are those who have mountedpower through military take-overs. Thereare also those who have out-lived their use-fulness but have nevertheless refused tohand over power, thus hampering the truetransfer of democratic tenets to Africa. Thisalso gives ground to justify the reason whyAfrica has been left behind in terms of de-velopment by most of Latin American andAsian countries, even though it was not solong ago that they were travelling in thesame lorry of underdevelopment. The newtechnologies are making the spread of in-formation almost uncontrollable even forthe developed world, and at a speed whichis quite unpalatable for most African lead-ers. Thus we can expect these leaders togive high priority to stemming the tide ofexpected criticism by muzzling those infavour of the transfer of such technologiesor by keeping their citizens in the dark sideof their rule by totally obliterating the com-mon man’s consciousness and by adoptingpolicies denying access to information.

I cannot help but ask myself if it is re-ally “ large sums of money” which need tobe raised for Africa to build in terms oftechnology. Or are we just forgetting andignoring what history should have taughtus by now? While it is a fallacy that allpoliticians are corrupt, keen followers ofevents in Africa will quite agree with mein the valid generalization that more thanhalf of the loans given by world donors andcreditors have never reached the continent’ssoil. If we seriously want to bridge the ever-widening gap between the North and South,Africans, of whom I consider myself to bea dedicated supporter, must learn to stepup efforts in tackling their own problemsinstead of heavily relying on foreignbailouts. If not, Africa shall remain a poorcousin of the developed world.

We must also not forget that help is al-ways slow in coming when Africa needs itmost. There can be no better example toillustrate this than when Rwandans wereabandoned to their fate while the Europeancommunity and America worked to mini-mize the bloodshed in the former Yugosla-via. We now see the speed and ease at whichbillions of US dollars pour into the econo-mies of the former Warsaw Pact countries,most of which are rife with civil wars. Allof which vindicates the belief that Africashall never be offered that political um-brella provided for former Cold War en-emies.

On their part, donors and creditorsshould stop dishing out money directly toAfrican governments. It is high time thatthe North tried working with indigenous orjoint companies when carrying out devel-opment programmes in the South, providedthat the identity, strategy and objectives ofthe companies involved are clearly spelt outand that they agree to a group continuallymonitoring their activities and also agreeto sign a pact forbidding them from havingaccounts outside the country.

In conclusion, if any veritable pro-gramme is to succeed in Africa, politicalscientists should engage themselves in find-ing answers to the following age-old ques-tions: why, when and how did Africa getitself beset with so many carking problems

L E T T E R S T O T H E E D I T O R

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N o 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

PAGE AND SCREEN . . . . . . . . . . 4

PEOPLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

C O N T E N T S

F O C U S

A l l a r t i c l e s a r e f r e e o f c opy r i gh tres t r i c t ions and can be reproduced,i n wh i c h c a s e t h e ed i t o r s wou l dapprec ia te a copy. Pho to s ca rr y ingno copyright mark © may be obtainedb y t h e m e d i a o n d e m a n d .

U N E S C O S O U R C E S

Editorial and Distribution Services:UNESCOSOURCES, 7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP. Tel.33 1 45 68 16 73. Fax. 33 1 40 65 00 29.This magazine is destined for use as an infor-mation source and is not an official UNESCOdocument. ISSN 1014-6989.

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

3. . . . . .

Pages 6 to 16

BEYOND THE MONUMENTS:

A LIVING HERITAGE

PLANET:

Education• A QUESTION OF PRIORITIES . . . . . .18

Media

• FOR 365 DAYS OF FREEDOM . . . . . .20

Film• OUT OF BREATH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Scientific cooperation• THE GAIN AFTER THE DRAIN . . . . 23

LOOKING AHEAD . . . . . . . . . . 24

René L E FORT

Cover photo: © MAGNUM/Steve Mac Curry.

A new vision.

Educationin Latin America.

The high price of freedom.

WHAT WE MAKE THEM

I N S I G H T

L ong be f o r e t h e UN Wor l d Con f e r en c e s on Women ,

Human R i gh t s o r Popu l a t i on , t h e pa s s i on s and t en s i on s

t he s e s ub j e c t s e voke r an h i gh . Tr ue , t h e s ub j e c t ma t t e r i n

ea ch c a s e t ou ched on r e l i g i ou s o r c u l t u r a l , and even

po l i t i c a l , t a boo s . By c ompa r i s on , t h e open i ng o f t h e “ C i t y -

s ummi t ” i n I s t anbu l r a i s ed ba r e l y a r i pp l e . Shou l d t h i s b e

r ead a s a s i gn o f l a s s i t ude v i s a v i s t h e s e “g rand mas s e s ” ,

t h e e f f e c t s o f wh i c h a r e r a r e l y f e l t i n t h e immed i a t e

a f t e rma th? I s i t an i nd i c a t i on t ha t c i t i e s a r e no t a “ho t ”

enough s ub j e c t ? O r c an i t b e r ead a s an adm i s s i on o f

impo t en ce i n f r on t o f an u rban exp l o s i on t ha t r ende r s

i l l u s o r y any a t t emp t t o manage t he f u t u re ?

I n l e s s t han 10 yea r s f r om now, mo re peop l e w i l l l i v e i n

t he c i t i e s t han ou t s i d e o f t h em . Mo s t o f t h i s g r ow th w i l l

t ake p l a c e i n t h e t h i r d wo r l d . By 2015 , d eve l op i ng c oun -

t r i e s w i l l b e home t o 27 o f t h e wo r l d ’s 33 “mega - c i t i e s ”

(mo r e t han e i gh t m i l l i o n i nhab i t an t s ) . Bombay, J aka r t a ,

Ka ra ch i , L ago s , S ao Pau l o and Shangha i w i l l e a ch s he l t e r

mo re t han 20 m i l l i o n peop l e .

The ob j e c t i v e i s no t t o r e ve r s e t h e t r end , bu t t o p r even t t h e

c i t y o f t omo r r ow f r om be com ing t he home o f a l l o f s o c i -

e t y ' s i l l s . How? The t oo l s a r e a l r eady ava i l ab l e , bu t , f o r

t he mo s t pa r t , on l y on pape r. Wha t i s m i s s i ng i s t h e hand

t o gu i de t h em and t he head t o l e ad t hem .

The p r epa ra t o r y wo rk f o r Hab i t a t I I empha s i z ed t ha t t h e

so l u t i on l i e s i n g i v i ng p r i o r i t y t o t h e g r a s s r oo t s : t h e

i nhab i t an t s and t he o r gan i za t i on s t ha t d i r e c t l y r ep r e s en t

t hem . Ce r t a i n l y, no t h i ng c an be a ch i e ved w i t hou t t h em - i n

t he u rban env i r onmen t mo re t han anywhe re e l s e . Bu t t o

make t hem ca r r y t h e c and l e a l one , t o m in im i ze s t a t e

i n vo l v emen t o r t o a vo i d i n f r i ng i ng upon t he ho l i e r- t han -

t hou l aw s o f t h e ma rke t - p l a c e , wou l d ma rg i na l i z e t h e i r

a c t i on s , howeve r bene f i c i a l t h ey may be .

A s ound u rban po l i c y i s e s s en t i a l . And i t w i l l wo rk p r ov i ded

i t i s c on c e i v ed by a l l t h e a c t o r s c on c e rned and app l i e d f r om

bo t t om t o t h e t op .

gongs and lutes in recountingthe woeful tales of loversseparated by battle, vixens androyal intrigue.

● Viet Nam - Court TheatreMusic: Hat Bôi, Anthology ofTraditional Music, UNESCO/AUVIDIS 1995, 145 FF.

THE UNESCO COURIERSocieties have always beenconfronted with the plagueknown as corruption. The Juneissue seeks to uncover its roots inanalyzing the motivationsinvolved and its various forms.The articles also focus oncorruption’s latest phase linkedto the market's globalizationand the formation oftransnational mafias. But aboveall, this issue asks about thedangers unleashed againstdemocracy and enumerates themeans to effectively fight this“virus of power” which couldcompletely throw off the world’seconomic equilibrium andcountries’ cherished politicalfreedoms.

TALENTED WOMENNalda, Aminata, Babriela,Ramrati and Mel - they comefrom different backgrounds inplaces as diverse as Mali,Colombia and Australia, yet allshare one thing: they arecraftswomen. By presenting theirwork, the book tells the stories oftheir lives and how they haveachieved “fulfilment throughtraditional techniques which theyhave managed to adapt to the

requirements of contemporarysociety ... by linking the pastwith the present, daily experi-ence with that of dreams, theordinary with the sublime andthe useful with the artistic.”

● Talented Women, editedby Jocelyne Étienne-Nugue,Women plus series, UNESCO1995, 112 pp., 130 FF.

CULTURAL DYNAMICS INDEVELOPMENT PROCESSESBased on papers submitted tothe international conference ofthe same title, organized in theNetherlands in 1994, this bookuncovers the “missing link” - thecultural dimension deemedessential if we are even to hopeof attaining sustainable humandevelopment in reducing thewidening gap between rich andpoor while assuring naturalresources for future generations.Cultural anthropologists, socialscientists, environmental andhealth specialists point to thefailure of “ready-made”imported development models -from the ecological disasters ofmisused pesticides to the harm

4. . . . . .

BOOKS

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

The Organization's publicationsand periodicals are on sale at theUNESCO Bookshop as well as inspecialized bookstores in morethan 130 countries. In eachMember State, books andperiodicals can be consulted insubscribing libraries.For more information: UNESCOEditions, 7 Place de Fontenoy,75352 Paris 07 SP.Tel: (33 1) 45 68 49 73,Fax: (33 1) 42 73 30 07,I n t e r n e t : H T T P : / / W W W.UNESCO.ORG

COMPACT DISCS

resulting from the refusal tovalorise women’s roles withinfamily structures differing fromthe western nuclear family unit.While pointing to past mistakes,the articles try to come to termswith the giant question markwhich culture represents - howcan we incorporate thisdimension when designingprogrammes and projects? Thepapers elucidate the complexi-ties involved by thinking throughconceptual problems and alsofocusing on the specificinteractions between culture andagriculture, health and educa-tion. All of which provides thefodder needed for policy-makers, researchers andstudents to further their discus-sions in finding alternativesolutions.

● Cultural Dynamics inDevelopment Processes, editedby Arie de Ruijter and Lietekevan Vucht Tijssen, UNESCO/Netherlands Commission forUNESCO 1995, 285 pp., 80 FF.

WORLD GUIDE TO HIGHEREDUCATIONThe third edition offers a myriadof essential details concerningthe higher education systems ofsome 160 states. With succinctprofiles describing eachcountry’s institutional structure,teaching requirements, degreesand diplomas awarded as wellas the requirements for entry atevery level, the guide enablesreaders to evaluate the aca-demic and professionalqualifications awarded. The aimis to contribute to internationalmobility by making it easier torecognize ‘foreign’ highereducation qualifications.

● World guide to highereducation - A comparativesurvey of systems, degreesand qualifications, thirdedition, UNESCO 1996, 571pp., 220 FF.

superhighways spreading, welive in a world of heighteningtensions and imbalances readyto explode with cultural differ-ences placed centre-stage. It isn’tenough to just condemn theviolence but anticipate andprevent it. Recognizing theteacher’s role in the socializationprocess, UNESO:IBE haslaunched a project to study andimprove their training in multi-and intercultural education. Thisbook presents the outcomes ofthe project’s initial teachertraining systems in eightcountries at various developmentlevels and in different regions.From Bolivia, the Czech Republicand Jordan to Senegal, thepapers point to the difficulty ingetting teachers and students toovercome simplistic thinking andethnocentric attitudes whenfaced with complex problemsconcerning their natural, social,cultural and economic environ-ments. By looking to the specificexamples of these nationalstudies, the book providesinsight in dealing with thecontradictory trends nowdominating: the standardizationof cultural patterns and thesearch for basic reference pointsfor cultural identity.

● Teacher Training andMulticulturalism: NationalStudies, edited by RaúlGagliardi, Studies in Compara-tive Education, UNESCO/International Bureau of Educa-tion 1995, 226 pp., 200 FF.

PERIODICALS

TEACHER TRAINING ANDMULTICULTURALISM:NATIONAL STUDIESWith the international market,AIDS and information

VIET NAM - COURT THEATREMUSIC: HAT-BÔIHat bôi , the traditional Viet-namese court theatre music firstcodified in the beginning of the14th century, has risen inpopularity since the 19th centurywith performing troupestravelling from village to village.More vocal than instrumental,the performance centres ondeclamations, with rants, moans,sighs and wailing expressingsorrow, vengeance, serenity andsuffering. The poetry and songrecitations are accompanied bybattle and rice drums, bronze

P A G E A N D S C R E E N

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

5. . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

JEAN CLOTTES:A CULTIVATED CAVE MAN

JAMEL BALHI:REFUSING ALL LABELS

Jean Clottes is convinced thathe will live to be one hundred.

“I’ve already warned my childrenand my seven grandkids. Youknow, prehistory is a preservative- I’m constantly learning andkeeping myself in shape.” Thehealthy optimism of this French

prehistorian, who looks a goodten years younger than his age of63, lives on more than that: thechance he has had - or that he hasmade happen - throughout hislife.

At 20, Clottes almost missedhis calling. Initiated as a child tothe mysteries of grottoes with afather impassioned by speleologywho made him “crawl into holeswhere adults couldn’t fit ”, this ac-tivity was nothing more than ahobby. “One day, my father founda sepulchral grotto with the re-mains of human skeletons. This isthe kind of thing that really gets akid’s imagination.”

His cave experiences sooncaught up with him. Becoming anEnglish professor at a college inFoix, his home region, he begantaking university classes in pre-historic archaeology during hisspare time. After writing a thesison the dolmens of Lot - whichtook 12 years of work and cer-tainly some heated moments inhis family life with so much time

and energy focused on his research- he applied for the job of prehis-toric antiquities director for theMidi-Pyrenees region withoutexpecting much... And he got thejob! Four years later - almost notime at all as anyone familiarwith the French administrationknows - he earned a transfer tothe Ministry of Culture. “For me,this was an extraordinary suc-cess. You’ve got to realize thatfor 15 years I had been an Eng-lish professor.”

He started his new career ata good time, with several big dis-coveries leading him to special-ize in cave drawings of which heis now an expert known world-wide. Another “surprise” came in1991 when he was elected presi-dent of the International Councilon Monuments and Sites. Be-coming a close mate ofUNESCO, he is consulted everytime a country proposes inscrib-ing a prehistoric site on the WorldHeritage List. In December 1994,it was Clottes whom the Organi-zation turned to in dealing withthe thorny dossier of the Foz Coasite in Portugal (see Sources No.68). Based on his report,UNESCO’s last General Confer-ence decided to turn priority at-tention to the protection of theworld’s cave drawings.

“The gigantic museum whichexists in nature is exposed toenormous damage. Actually, ifyou look at things from an ar-chaeological point of view, eve-rything ends up disappearing.What will remain of our own civi-lization in a 1,000 years?” Per-haps a few bones from a century-old preshistorian found in a cav-ern in the Foix region...

Sophie BOUKHARI

Jamel Balhi began his lifethe day he decided to jog

around the world. “I love to read,write, take photos, long walks,jog and meet people - to feel free.I’ve managed to combine all ofthese activities in one thing: thevoyage.” But his kind of travel-ling is the tour guide’s worstnightmare: entirely by foot, instretches of 60 to 80 km. “I gostraight into the heart of the coun-try, where no tourist agency cantake me.”

It all began ten years ago,“ the day I decided to go for teaat a Chinese friend’s house. Imet him by chance on asidewalk in Munich waiting fora taxi.” At 23, he stopped hisstudies in physical therapy. “Ithought of leaving right away,but after sleeping on the idea,

I told myself that it would bebetter to organize the trip. Ittook me a year: I read an enor-mous amount and took Chineseclasses.” Why China? “It wasfar, unknown and certainlydangerous. It wasn’t reallyChina that attracted me andeven less the tea - I prefer coffee- but the route,” a total of 27,000km in two and half years.

Since his return in 1990,Jamel has fallen into his old wayswith Norway’s North Cape, Aus-tralia, Scotland... By “freelancingin religion” or “taking a littlefrom each one in making myown”, Jamel hit the roads of faithon 15 May for a year-long jour-ney from Lourdes to Lhassa byway of Rome, Jerusalem, Meccaand Benares. “The idea camefrom staying with people of reli-gions which are very different butwhose welcome was all the sameso kind.” This is what led him tobelieve in the existence of a “uni-versal conscience” reaching be-yond particularism and differ-ences.

It is a conviction shared byUNESCO which has providedhim with support and entrustedhim with several “small man-dates”. A professional photogra-pher, Jamel will fill in icono-graphic gaps in the “Silk Roads -Roads of Dialogue” which criss-cross those of faith. He will alsoact as a “bridge” with AssociatedSchools found along the way andclubs affiliated with the Interna-tional Fund for the Developmentof Physical Education and Sports.“When I come back, I’ll point outthose which are in the most diffi-cult positions.”

Naturally talkative, Jamelcloses like a clam when the dis-cussion turns to his childhood,parents and origins. He fires a“No comment!” before leaving. “Iwas born on an April day in 1963and since then I have crossed 75countries while jogging and shak-ing the hands of thousands of peo-ple. I won’t let myself be labelled.I embarked on these voyages pre-cisely to break down the borderswhich lead to war.”

S. B.

● “I hope that this SQUAREOF TOLERANCE will be abeacon, a symbol throughout theworld so everyone will remem-ber what intolerance canbreed,” declared Leah Rabin, 1May, during the inauguration of

the garden created at UNESCOin homage to her husband,Yitzhak Rabin, who wasassassinated on 4 November1995.Designed by Israeli artist DaniKaravan, the square “recalls the

path of peace, with its shadowsand light,” said Director-General Federico Mayor, inunderlining that “tolerance isneither docility, concession norindulgence, but rather theoverture to the other.”

Israeli Prime Minister ShimonPeres paid tribute to the courageof Yitzhak Rabin “who permittedthe pit of hate to be filled... inorder to sow the flowers of hopeon the battlefields soaked withblood.”

(Ph

oto

All

Rig

hts

Re

serv

ed

)

(Ph

oto

All

Rig

hts

Re

serv

ed

)

P E O P L E

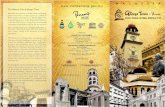

The Fes Medina - an urban historic centre par excellence - wasinscribed on the World Heritage List in 1981 (Photo ©

Patrimoine 2 001/ Fondation La Caixa, Éric Bonnier).

ALL

ARTI

CLES

ARE

FRE

E OF

COP

YRIG

HT R

ESTR

ICTI

ONS.

SEE

P.3

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

F O C U S

7. . . . . .

BEYOND THE MONUMENTS:

A LIVING HERITAGE

T h i s m o n t h ’s d o s s i e r

The happiest days of our lives? Or theworst? Twenty years, in any case, is a

good time to take stock. The Conventionof 1972 concerning the Protection of theWorld Cultural and Natural Heritage is acase in point. Four years after launching theprocess of reflection which shook certainof its fundamental ideas, this text, ratifiedto date by 146 States, appears to have founda second wind, animated by a more bal-anced notion of heritage.

The convention was adopted byUNESCO’s General Conference at a timewhen decolonization, nearly accomplished,was opening the way for recognition of theplanet’s cultural diversity. It was nonetheless the outcome of concepts born at thebeginning of the century, when the concertof nations, dominated by European pow-ers, left little place for other voices to beheard. This is the paradox of the conven-tion and the “guidelines” which ruled itsapplication, and notably inscription ofproperties on the World Heritage List.

When, in 1992, the hour came to re-view the Convention’s achievements, itsanomalies also came clearly into focus. Thetext appeared as favouring a “monumen-tal” vision of heritage, corresponding towestern aesthetic canons. A close exami-nation of the List revealed, for example,

many disparities both in geographical dis-tribution and with regard to the propertiesthemselves: a preponderance of Europeanand North American sites (over half); ofhistoric cities and religious edifices; ofChristianity (72% of religious sites) and ofdefunct civilizations, to the detriment ofliving cultures. This analysis also shed lighton the disproportion of cultural (78%) andnatural (22%) properties and the necessityto break down the divisions between thetwo categories.

HUMANIZ INGThis analysis led, in 1994, to a revision ofcriteria in line with a new “global strat-egy”. Born of the recognition that theWorld Heritage List, out of step withprogress made over 20 years in the hu-man sciences, risked losing its credibil-ity by privileging the monuments of a fewisolated cultural basins, this new approachaimed first of all, at progressive elimina-tion of the notion of the artistic masterpiece,linked with the old “Seven Wonders of theWorld” logic. There is no question, ofcourse, of tearing down the notion of herit-age - Mont-Saint-Michel or the Taj Mahalwill always have their place on the List.Rather, the aim is to humanize in order touniversalize.

Secondly, the new vision is moreclearly historical and anthropological,based to a greater extent on the social, cul-tural and spiritual significance of a site,rather than on its form. In Africa, Oceaniaor in the Caribbean in particular, what istransmitted from generation to generationis more a set of rules for the organizationof space than a tangible property.

The ideas developed by the World Her-itage Centre on cultural landscapes, sacredplaces or trade routes thus allow for rec-ognition of the specific cultural heritage ofhitherto marginalized regions. At the sametime, this process has produced a third re-sult: the recognition of the interactions be-tween cultural and natural sites.

In recent years, the List has been en-riched by several “non constructed” sites,such as Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park(Australia), inscribed in 1994, which theAborigines endow with strong spiritualpower and whose landscape they havemodified accordingly; the sacred Maorivolcanos of New Zealand; and the terracedrice fields of the Philippines. With their tan-gible and intangible dimensions, naturaland cultural, these sites testify to ancientcivilizations, often still alive, but almostalways threatened.

Sophie BOUKHARI

To liberate the notion of “heritage” from its predominantly western vision and an overly structuredapproach. Such is the new philosophy guiding the “global strategy“, which aims to open up the WorldHeritage List (see below).This idea breaks with an essentially “monumental“ conception that has its origins in Europe (p.8) , andis the fruit of years of reflection and debate, led by people such as Niger's Lambert Messan (p.10).Its application opens the way for recognition of far more complex sites, such as Abomey (p.15) thatincorporate the belief systems and traditional knowledge of living cultures. It also reconnects theartifically separated categories of “natural“ and “cultural” heritage by introducing the newclassification of “cultural landscapes” (pp. 9 and 12-13). These fundamental changes are accompaniedby a much more dynamic approach to conservation, based on the active participation of a wider rangeof actors, from local populations - as in the French town of Vezelay (p.16) - to international consortiumsas in the case of Vilnius in Lithuania (pp.11 and 14).

F O C U S

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

Przyluski as having advanced in 1553“that all belligerents should respect worksof art, but not only because of their reli-gious character”. Swiss jurist Emer de Vattelwrote early in the 18th century that “de-priving a people of that which makes theirhearts glad, their monuments and arts ... isto act as an enemy of the human species”.

According to Cleere, the renewal ofhistorical studies over this period, and theemergence of a linear view of history inwhich societies were seen as having cul-tural links extending back over time alsoreinforced the idea of a national or culturalheritage. “Relics of earlier phases were

seen to be important documents in record-ing that continuity, and as such they be-came worthy of care and preservation.”

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648,treaties began regularly to include clausesstipulating the restitution to their place oforigin of archives and works of art seizedin warfare. In 1815, writes Toman, the al-lies decreed the restitution of art workstaken to France by Napoleon on thegrounds, set down in a circular letter writ-ten by Lord Castlereagh, that their theft“was contrary to all principles of justiceand the practices of modern warfare”. By

D o s s i e r

8. . . . . .

THE DESIRE TO PROTECT AND PRESERVEHuman societies have always tried to preserve the sacred and the beautiful. A brief historyof an essentially human characteristic.

Nobody can deny that the wanton de-struction of temples, statues and other

sacred things is pure folly,” said Greek his-torian Polybius back in the second centurybefore the Christian Era.

Was he not expressing the same sort ofthinking that lays behind today’s efforts toprotect “cultural heritage”?

Throughout the ages, evidence can befound of the desire to protect the places andobjects held sacred to society; those thingsthat identified a people or a culture and tiedthem to a particular location or way of life.

In Europe, up until the Renaissance, theChurch was the main defender of the sa-cred. In 1425, Pope Martin V ordered thedemolition of new buildings which wereliable to cause damage to ancient monu-ments in Rome and in 1462, Pope Pius IIpronounced the Bull “Cum almannostram urbem” to protect the city’s an-cient monuments. In 1534, Pope Paul IIIestablished an antiquities commissionwith broad powers for the protection ofancient structures.

These measures were largely restricted toreligious edifices, were enforced with a cer-tain ambivalence and did not extend to thesacred sites and objects of others: the Ref-ormation in England used the monasteriesand abbeys of the outlawed Roman Catho-lic orders as quarries, while the Spanish sim-ply melted down ancient gold and silver ob-jects seized from the peoples of the colo-nized Americas.

Significant change came in 1666 whenthe Swedish monarch declared that all rel-ics from antiquity, including archaeologi-cal sites, were the property of the crown.“For the first time the intrinsic importanceof the remains of the past was acknowl-edged in a national legal code,” writesBritish archaeologist Henry Cleere in “ Ar-chaeological Heritage Management in theModern World”. Over the next two centu-ries several other monarchies followed suit.

At the same time, Europe’s jurists wereraising the idea that protection should beextended to works of art. Jiri Toman in hiscommentary on the Hague Convention“The Protection of Cultural Goods inArmed Conflict”, cites Polish jurist Jacques

the end of the 19th century most ofEurope’s monuments were protected bylegislation and a concerted effort was be-ing made to establish an agreement be-tween the nations of Europe to protect cul-tural heritage in times of war.

However, while each of these developmentsadded momentum to the idea of protection,cultural heritage remained essentially anaffair of the state. This began to change withthe establishment of the League of Nationsafter World War I. The League sought last-ing peace through universalism and intel-lectual cooperation, based on the recogni-tion of different cultures. Cultural heritagewas a major vehicle for working towardsthis ideal. The world’s outstanding monu-ments, archaeological finds and classicalworks of art were the heritage of the wholeof humanity. These works stood as testi-mony, not only to the genius of a particularpeople, but to human beings everywhere.

This idea underpinned UNESCO’sthinking when it took over the League’sactivities in this domain after World WarII. However, defining exactly what consti-tuted a heritage of “outstanding universalvalue” proved extremely difficult and thevision that prevailed was clearly eurocen-tric and monumentalist. Those cultures thatdid not build in stone or leave massive edi-fices had difficulty getting their “heritage”recognized.

A major turning point came in 1972with the UN Conference on the HumanEnvironment in Stockholm. For the firsttime, debates on preservation began to in-clude the environment. Culture and nature,if not seen as interactive, were at leastlinked. As a result, later that year,UNESCO’s General Conference adoptedthe Convention Concerning the Protectionof World Cultural and Natural Heritage.

With 146 states parties, it has becomethe Organization’s most “popular” con-vention. Now, at the close of the century,it is also broadening its vision, in an at-tempt go beyond the narrow categories ofculture and nature and to truly fulfil its mis-sion of protecting heritage that belongs toall of humanity.

Sue WILLIAMS

A C E RTA I N A M B I VA L E N C E

NAT IONAL TO UN IVERSAL

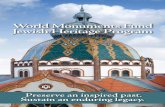

F R A N C E ' S M O N U M E N T A L M O N T - S A I N T -M I C H E L ( P H O T O U N E S C O / M . C L A U D E ) .

ALL

ARTI

CLES

ARE

FRE

E OF

COP

YRIG

HT R

ESTR

ICTI

ONS.

SEE

P.3

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

F O C U S

BEYOND THE MONUMENTSCultural landscapes represent a new vision that reconnects culture and nature, and opens the WorldHeritage List to a non-monumental heritage not previously acknowledged.

D o s s i e r

The Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park inthe Western Desert of Central Australia

is one of the continent’s best known land-marks. Its geological and landform features,including the vast sandstone monlolith ofUluru and the nearby rock domes of KataTjuta, are unique, and it is home to rare andscientifically important plant and animalspecies.

Uluru is also a sacred place for theAboriginal Anangu community. Accordingto Australian archaeologist and heritageconservationist, Sarah Titchen, “many ofits striking rock features are the trans-formed bodies or implements of the crea-tive heroes of Anangu religion. The con-servation and management of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park are guided byAnangu law and tradition, known asTjukurpa (the Dreamtime or Time of Lawor Epic Time) and involves, for example,the spacing of groups of people evenlyacross the landscape ensuring that over ex-ploitation of particular wild foods does notoccur.”

Is Uluru then a “cultural” or “natu-ral” site ? The answer, obviously, is that itis not only a combination of both, but thatboth the natural and the cultural aspects ofthe site are inextricably linked.

The shortcomings of the separate defini-tions of “culture” and “nature” have be-come increasingly apparent as more be-comes known about how people interactwith their environment and as rightful rec-ognition of cultural differences and valuesbecomes more widespread. It is now ac-knowledged, for example, that Aboriginaland Torres Strait Island peoples have playedan important role in shaping the Australiancontinent, or that the the world’s so-called“virgin forests” have, in fact, been man-aged to a greater or lesser extent by indig-enous peoples. If such is the case, asks Pe-ter Bridgewater, Executive Director of theAustralian Nature Conservation Agency,“what is this naturalness”, that outstand-ing “natural” sites require for inscriptionon the World Heritage List ?

“Everything is culture” affirms Berndvon Droste, Director of UNESCO’s WorldHeritage Centre. “Everything depends on

people or has been influenced by people.”To encompass this still emerging and moreanthropological vision of the world, andto change the World Heritage List from asimple catalogue of monuments to an over-view of the great diversity of the different

cultures that make up humanity, the WorldHeritage Committee, in 1992, adopted thecategory of “cultural landscapes”.

“These are places that have been cre-ated, shaped and maintained by the linksand interactions between people and theirenvironment,” explains Titchen, who alongwith Mechtild Rossler of the World Her-itage Centre has worked on explaining theconcept. “Their successful conservationdepends on the maintenance of theselinks.” There are now four “culturallandscapes” on the List, includingUluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in Aus-tralia and Tongariro National Park inNew Zealand, which had been previouslyinscribed as natural sites, the Rice Ter-races of the Philippine Cordilleras andSintra in Portugal (see pp. 12-13).

While maintaining the essential crite-ria that nominations for the List must beof “outstanding universal value”, theCommittee has settled on three types ofcultural landscapes: the clearly definedlandscape designed and created intention-ally by people, embracing gardens orparklands constructed for aesthetic reasonsand often associated with religious or othermonumental buildings and ensembles(such as Versailles in France and Potsdam

in Germany, both of which are inscribed ascultural sites); the organically evolved land-scape resulting from an initial social, eco-nomic, administratrive and/or religious im-perative, such as fossil landscapes (Stone-henge and Avebury in the U.K, also

inscribed as cultural sites) or continuinglandscapes that retain an active social rolein contemporary society closely associatedwith a traditional way of life (the rice ter-races of the Philippine Cordilleras); and theassociative cultural landscape, marked bypowerful religious, artistic or cultural as-sociations of the natural element rather thanmaterial cultural evidence (Uluru Kata-Tjuta and Tongariro National Parks).

“These new categories ensure a moreholistic approach to heritage conservation,and prevent pre-eminence being given toone set of values over another,” saysTitchen. “Most importantly, they accom-modate the past and living traditions of in-digenous peoples.”

Using a concept , described by anthro-pologist Howard Morphy as “ in between,that is free of fixed positions, whose mean-ing is elusive, yet whose potential range isall encompassing” also allows the WorldHeritage List a new flexibility to reflecthuman thought and perceptions and evolvealong with future archaeological and sci-entific discoveries; to develop a dynamicand truly universal approach to heritage andits conservation.

S. W.

9. . . . . .

“EVERYTH ING I S CULTURE”

M O U N TH U A N G S H A NR E C O G N I Z E DB Y T H EC H I N E S E F O RI T S C U LT U R A LA N D N A T U R A LI M P O R T A N C E( P h o t oU N E S C O /M . R o s s l e r ) .

F O C U S

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

“MR AFRICAN HERITAGE”Niger's diplomat Lambert Messan's battle for heritage preservation goes beyond stilted monumentsand standard parks. In Africa, nature, culture and daily life are indivisible.

P o r t r a i t

10. . . . . .

If UNESCO had to draw up a list of itshuman treasures, Lambert Messan,

Niger’s Ambassador to the Organization,would surely be on it.

A keen economist and expert in theeducational science, Messan isn’t someonecontent just to open flower shows. His lat-est job has added a cultural string to hisbow and he is now considered a sortof unofficial “Mr African Heritage”at UNESCO.

He arrived at this by an oddroute. “I was all set to teach math-ematics, which is still my hobby, butI was diverted by events,” he ex-plains. Paralysed after a car acci-dent when he was 25, he had to un-dergo lengthy treatment in Paris,where he began his diplomatic ca-reer. At the age of 37, he receivedhis first ambassadorship.

“My physical handicap wassomething which I had to deal within a such a way that I could lead a‘normal’ life,” he says. With a bril-liant career taking him to Belgiumand Canada, he was then named am-bassador to UNESCO “after thedeath of President Seyni Kountché”.

A LONG BATT L E“When I got here in 1988, I was as-tonished to see that Niger wasn’t repre-sented on the World Heritage List,” he says.In fact, Niger had never suggested any sitefor inclusion on the List, a situation whichMessan soon corrected. “I asked for anexpert to be sent to look at possible sitesand this was agreed to,” he says. As aresult, in December 1991, the natural re-serves of Air and Tenere were inscribedon the List.

For Messan, it was just the start of along battle which he extended to the wholecontinent. “As I was chairman of the Af-rican group, I asked the tough question: ifheritage sites belong to all the world’speoples, why are some regions seen asmore ‘universal’ heritage-wise than oth-ers?”

Sub-Saharan Africa has only 42 listedsites (25 natural, 16 cultural and onemixed) - less than 10% of the whole List.Also, only two-thirds of the region’s 45

countries have ratified the 1972 WorldHeritage Convention.

There are several reasons which mightexplain this modest share. To begin with,few African states have the technical re-sources to “draw up a list of all the differ-ent sites and undertake the work in prepar-ing the dossiers which must be presented.”

They also concentrate more on moderniz-ing society than on preserving traditionalheritage. In addition, not all of the coun-tries’ laws provide for protection and con-servation and such legislation has long beena prerequisite for a site’s inscription on theList. “Yet in Niger, where there’s a livingheritage, conservation is often integratedin people’s daily lives,” Messan says.

But beyond these somewhat technicaldifficulties, there lies a broader probleminvolving conceptions. “Most of our coun-tries can’t meet the conditions required”to earn a place on the List, explains Messanin pointing to an inadequacy between thecriteria for inscription, as defined by theWorld Heritage Convention (which con-cern only very specific kinds of culturalproperty and ignore immaterial heritage)and aspects of African culture and spiritu-ality, which are often hard for outsiders tospot, and defy simple classification.

“In the West, the cultural and the natu-ral represent two distinct domains. In Af-rica, they form a whole,” he says. “Ourperception is global: the religious, social,economic and the environmental functionsare all knitted together.” In many cases,so-called natural sites have only been pre-served because of their social and cultural

importance. This is notably the casefor Africa’s sacred groves. Protectedby tradition, they usually contain anextraordinary biodiversity at thesame time as having a religious andsocial purpose. Seen as a kind ofsource or womb with the power toregenerate humans, they are acces-sible to only a few privileged peo-ple. They have never been includedin inventories nor have they beenthe subject of in-depth studieswhich would enable us to appreci-ate their “special universal” valueso that the most representative ofthem might be inscribed on theList.

F O S S I L SMessan is working closely withUNESCO in its efforts to draw upthe most representative list possibleof the world’s cultural diversity.He is pleased about the adoption

of the concept of cultural landscapes (seepage 9) and about the definitions of sev-eral new kinds of properties, such as cul-tural itineraries and trade routes whichenable inclusion of nomadic civiliza-tions.

“In Niger, we are very interested in thischange,” he says. “We have on our terri-tory routes for the salt trade, for gold, androads heading to Mecca...”

He himself is getting ready to hit theroad to Addis Ababa at the end of July forthe next of a series of sub-regional confer-ences. “We have to make African leadersaware of the new approach, which is stillpoorly understood. When I proposed thelisting of Air and Tenere, the first reactionof officials in Niger - who were concernedthat the region might end up as a museumpiece - was to say: ‘Are they trying to turnus into a fossil?’”

S.B.

V I S I T I N G P A R I S ’ N A T U R A L H I S T O R Y M U S E U M( P h o t o © a l l r i g h t s r e s e r v e d ) .

ALL

ARTI

CLES

ARE

FRE

E OF

COP

YRIG

HT R

ESTR

ICTI

ONS.

SEE

P.3

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

F O C U S

11. . . . . .

D o s s i e r

A COMBINED EFFORTA new range of partners are entering into the protection, preservation and restoration of worldheritage. Why have they decided to get involved and what do they expect from UNESCO ?

Yves Dauge is Mayor of the Frenchcity of Chinon, which has offered its

know-how and financial help to the Lao-tian city of Luang Prabang, inscribed on theWorld Heritage List last December.

“Chinon is one of those cities of the worldwith a rich heritage that stretches back intohistory, which gives it an importance thatgoes beyond local or national borders. Assuch we consider it our duty to share ourexperience with with other cities. Classi-fying a monument is easy, but classifying acity is much more complex. Tourists arrive,new money is injected, investors specu-late....

“So many questions are raised: can wecontinue to develop commercial businesses,or build low-cost housing? How do we en-sure that the tourism industry benefits thelocal population? What legal structureneeds to be put into place? It’s not enoughto just send in experts. Their interventionneeds to be part of a logical chain of ac-tion. This is what we aim at with decentral-ized cooperation, which is what we are de-veloping with Luang Prabang.

“More specifically, we are working to-gether on a plan to safeguard and restorethe city. This entails the preparation of aninventory of the city and the elaborationof a judicial framework. Restoration workwill be spread over three years and the cost,an estimated three million French francs,will be shared between Luang Prabang andthe region of Chinon, French ministries,international funding agencies and privatesponsors.

“The following phase will concentrateon providing advice and direction for pri-vate investment. Issues such as garbagedisposal must be dealt with, along with thedevelopment of the electrical grid and theprotection of surrounding wetlands. We arealso planning to open a “ heritage house ”,which will serve as a permanent workshopto teach the local people how to restore andimprove their habitat. This is particularlyimportant, because once the experts havepacked up and gone, it will be up to theLaotians to continue.

“All of this is being done under the ae-gis of UNESCO which, in a sense, legiti-mizes our involvement. Without this, I don’t

believe that decentralized cooperationcould work. UNESCO is often criticized ashaving no money, but it has something bet-ter: an authority to delegate.”

Ismail Serageldin is Vice-President ofEnvironmentally Sustainable Develop-ment at the World Bank which is work-ing with UNESCO on the restoration andpreservation of six historic cities.

“The rapidly urbanizing developing worldfaces many social and economic chal-lenges, from population growth and theinflux of rural migrants to an evolving eco-nomic base. Crumbling infrastructure,poor and over-stretched social services,rampant real-estate speculation and weakgovernments all contribute to putting tre-mendous pressure on central cities, oftenthe loci of invaluable architectural andurbanistic heritage. We have a number ofactions to propose to decision-makers forthese problems, but the inner historic coresrequire special attention. They are an es-sential part of how we define ourselves.Their conservation helps maintain the veryfabric of society.

“Thus, a case for the Bank’s additionaleffort to deal with historic cities can bemade in terms of its traditional mandateof poverty reduction and economic de-velopment - with the added attention tothe uniqueness of the site. It is here thatthe nature of the partnerships requiredbecomes obvious. The Bank has tradi-tionally had a strong link with policy is-sues and a long experience with projectsdealing with infrastructure, housing, mu-nicipal finance and urban transport.UNESCO has a long experience in thedesign of sensitive treatments for historicareas, others have expertise in restoration,while foundations such as the Aga KhanTrust for Culture have effective links at thegrass roots and long experience in conser-vation and revitalization. UNESCO al-ready has a large number of studies aboutmany of these cities completed or on thebooks.

“Looking at the various cities with astrong historic significance where the Bankwas likely to finance important develop-ments in the next few years, it was deemed

wise to try to collaborate up front, draw-ing on the available or planned UNESCOstudies. The cities where the intersectionof UNESCO plans and those of the Bankmade it most promising to focus wereSt.Petersburg, Fes, Samarkand, Hue,Sana’a and Vilnius. We are planning topursue these although there is already abroad interest in many others.

“We are a long way from a clear for-mula on how best to engage all the inter-ested parties, or even how to consolidatethe central relationship between UNESCOand the Bank. But we are determined tokeep it unbureaucratic and pragmatic, re-sults focused and forward looking. We willlet our experience guide us in the bestmodes of collaboration, between UNESCOand the Bank and with the other partners,whose participation is essential for ulti-mate success, not least the communitiesconcerned.”

André De Marco is Director of Commu-nication for pharmaceuticals giant,Rhône-Poulenc, which is working withUNESCO on two world heritage fronts:restoration and education.

“Rhône-Poulenc considers that beyond itseconomic goals, the enterprise has civicresponsibilities towards the community.One of the forms of this citizenship is pa-tronage. The Rhône-Poulenc Foundationis developing a programme of patronagewhose main direction is the protection ofcultural, artistic and natural world herit-age. We believe very much in the idea that‘we don’t inherit the world of our ances-tors, we are borrowing it from our chil-dren’.

“Rhône-Poulenc is working on twoprogrammes with UNESCO, including therestoration - in collaboration with the Vi-etnamese government - of two of the pavil-ions in the imperial city of Hué and two ofof King Tu-Duc’s tombs. Our scientificteams have provided help to protect the newtimber used to build the pavilions from ter-mite damage. We are also contributing toa project aimed at educating young peo-ple on the protection of the world’s culturaland natural heritage.”

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N ° 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

THE FOUR NEW “CULTURAL LANDSCAPES”

TONGARIRO NATIONAL PARK (NEW ZEALAND)

12 . . . . . .

F A C T S I N F I G U R E S

Tongariro National Park covers 79,000 ha in the North Island of New Zealand. The natural landscape is largelyuntouched. Controlled ski fields cover three percent of the total area.

ULURU-KATA TJUTA NATIONAL PARK (AUSTRALIA)

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park covers 132,566 ha of arid ecosystems close to the centre of Australia. It has been hometo the Anangu people for some 5,000 years.

Since the World Heritage Committee adopted the category of “cultural landscapes” in 1992, it hasaccepted four such inscriptions onto the World Heritage List.

“The breath of the mountain is my heart” ishow the Ngati Tuwharetoa people of theMount Tongariro National Park in NewZealand express their affection and greatreverence for this active volcanic landscape,which is linked by mythology to the arrival ofthe first Maori from Hawaiki some 700 to1400 years ago. The mountains represent thegod-like ancestors, the tupuna. They are alsoa source of mana (prestige), cultural andtribal identity, and spirituality. In September1887, the paramount chief of the NgatiTuwharetoa, formally presented the summitsof Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and part of Ruapehuto the New Zealand government, leading tothe establishment of the country’s first nationalpark, and at that time, only the fourth one inthe world.

The rock domes of Uluru-Kata Tjuta Natio-nal Park are located on the traditional landsof the Anangu people. According to Anangulegend, the surface of the Earth was oncefeatureless. Places like Uluru and Kata Tjutadid not exist until Anangu ancestral beings(in the forms of people, plants and animals)started to journey across the land. Theseancestral beings formed or moulded thelandscape as they passed through it. Theirtravels and activities linked places throughoutthe country by iwara (paths or tracks) ofwhich Uluru and Kata Tjuta represent mee-ting points in a vast network. Park conserva-tion and management is today guided byAnangu law and tradition known as theTjukurpa. “Tjukerpa is real” says Yami Les-ter, Chair of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board ofManagement, “it’s our law, our language,our land and family together.”

(Pho

to ©

Dr.

Sara

h Tit

chen

)(P

hoto

© c

ourte

sy o

f Ne

w Ze

alan

d To

urist

Boa

rd)

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N ° 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

13. . . . . .

F A C T S I N F I G U R E S

MOUNTAIN RICE TERRACES (PHILIPPINES)

The rice terraces of the island of Luzon in the northern Philippines are located at between 700 and 1500 metre abovesea-level on slopes of up to 70 degrees. They have functioned for about 2,000 years.

THE CITY OF SINTRA (PORTUGAL)

The former monastery of Pena, transformed by King Ferdinand II, is considered a forerunner of the celebratedNeuschwanstein Castle constructed by Louis II in Bavaria.

The 3000 history of the rice terraces of theCordillera Mountain Range in the Philippinesis intertwined with that of its people, theirculture, customary activities and theirtraditional practices of environmental mana-gement and rice production. The steepness ofthe slopes means that all tilling and mainte-nance is done manually. A complex system ofdams, sluices, canals and bamboo pipestransfer water from the highest terrace to thelowest, finally draining into a river or streamat the base of the valley. Each of the fourclusters of terraces inscribed on the WorldHeritage List is composed of a buffer ring ofprivate forests (muyong) the terraces them-selves, a hamlet and a sacred grove whereholy men (mumbaki) perform traditional ritesand sacrifices relating to rice production.

Sintra owes its development to its coolsummers and mild sunny winters, fertile soilsand proximity to the Tage River. The city hasbeen conquered, destroyed and rebuilt manytimes over by Romans, Arabs, Moors and thePortuguese. In mediaeval times the RoyalCourt settled there, building sumptuous villasand country homes, parks and gardens. Thesite’s isolation also attracted monks whoestablished monasteries there... Growthpeaked with the artist-King, Ferdinand II(1836-1885), who transformed one of thesemonasteries (Pena) into a ‘Romantic’castle,complete with a park of rare and exoticplants, decorated with fountains, streams,cottages and chapels. Sintra is seen as theprototype of European romanticism: a perfectcommunion between nature and ancient mo-numents that are the stuff of architecturalfantasy .

(Pho

to U

NESC

O)(P

hoto

© H

OA-Q

UI/A

. Ev

rard

)

F O C U S

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

in need of repair, but overall the city is infair shape considering its turbulent history.

“Of the 1500 buildings in the historiccentre, about 119 are actually caving in”says Augis Gucas, Manager of the munici-pality’s Monuments Protection Depart-ment. But rebuilding and restoration areonly one aspect of the city’s much needed“revitalization”.

“Many of the buildings are empty be-cause the inhabitants were moved out morethan five years ago so that renovationscould be carried out under a restorationprogramme (the fifth such plan attempted

since the 1940s). But work has noteven started on many of them, andhas had to be interrupted on the oth-ers because of a lack of fund,” re-ports Lithuanian journalist RusnéMarcénaité. “The municipality al-located a meagre $700,000 dollarsfrom its budget - enough to paint afew frontages or to reconstruct asmall buildings. The church alsoowns a big chunk of the city, but itdoesn’t have any money either.”

The municipality attempted torent buildings by auction, but thisfailed to attract investors, whowould rather have a title deed thana lease. “And then,” said Marcé-naité, “life in the business worldhere is very tough, and bankrupt-cies are rife. Few business-peoplewere ready to add huge buildingcosts to their overheads. Thosewho took the risk found them-selves confronted withmindboggling administration,

which they often simply ignored.“The result is that much work was car-

ried out without any consultation or coor-dination with the heritage protection au-thorities. The new inhabitants claim theseauthorities are too strict, and that if theycomplied with the requirements they wouldhave to draw water from a well, cook andheat the building with a stove and placethe toilets outside.

“Effectively, before any work can beundertaken, occupants are supposed to getapproval from some 29 different heritageauthorities. Consequently the main activ-ity of architectural firms is not designing

REVITALIZING VILNIUSGoing it alone has not worked in the Lithuanian capital, where a new joint approachis now being tried to breathe new life into the city.

D o s s i e r

14 . . . . . .

(Pho

to ©

Rai

mon

do U

RBAK

AVIC

IAU

S).

According to legend, the Grand DukeGediminas was hunting in the area

that is now the city of Vilnius - where therivers Neris and Vilnia flow together - anddreamed of a wolf who howled with thepower of 100 wolves. A wizard explainedthat the dream was a message from the Godsthat they wished to found a city on the site- a city whose fame would spread as far asthe wolf’s howl could be heard. GediminasCastle was built upon the Grand Duke’sorders on the top of the highest hill. Today,residents take their guests there to give themwhat is undoubtedly the best view of the

city that for centuries has been the politi-cal, religious, scientific and cultural heartof Lithuania.

The old city today covers almost 360hectares and is home to 31,000 residents.Over the course of its long history, whichhas seen at least seven major fires andmany wars, it has been rebuilt severaltimes. However, it is this rebuilding thathas given the town its special character, re-flecting the architectural styles of theGothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Classi-cal periods,which saw its inscription onUNESCO’s World Heritage List in Decem-ber, 1994. Some of the buildings are badly

but collecting signatures. They argue that‘outsiders’ would not be able to collectthese signatures by themselves, and remindtheir clients that permission costs... An-other apparent anomaly is that new own-ers are not required to carry out any re-pairs or maintenance.”

W O R K I N G T O G E T H E RThe confusion that has reigned in the past -largely brought about by the huge social andeconomic changes that accompanied the fallof communism - made Vilnius a perfectcandidate to test a new approach to resto-ration of old city centres, based on a con-sortium comprising private foundations,local and national government and interna-tional organizations, including UNESCOand the World Bank.This consortium ischarged with raising the funds and findingthe expert help to get the job done. In thecase of Vilnius, which is one of six old citycentres being tackled in this way, Denmarkand Scotland are helping out with advicebased on their own experience.

The initial aim is to draw up a list ofpriority infrastructure investments, as wellas a heritage management plan. This isbeing worked on at the moment. Ways ofstimulating private and public investmentswill also be studied, as well as ways ofkeeping the city’s residential characterrather than turning it into a shopping mallor rows of offices. An institution will becreated to manage the old town’s affairs.UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre has alsoopened an office there, on premises offeredby the Lithuanian government.

The vision is to preserve Vilnius’ spe-cial character, and at the same time makeit a city ready to face the 21st century. Al-though planning and strategy-making taketime, and perhaps create the impression thatlittle is being done, the ball is rolling, andgathering momentum. The World Bank hascommitted $190,000 to some of this essen-tial preliminary work, and although this isonly a drop in the bucket, the various part-ners involved are all confident the neces-sary millions will be there when needed,and that Vilnius will eventually resume itsplace as one of the great capitals of Eu-rope.

S.W.

ALL

ARTI

CLES

ARE

FRE

E OF

COP

YRIG

HT R

ESTR

ICTI

ONS.

SEE

P.3

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

F O C U S

. 15. . . . . . .

THE DOUBLE LIFE OF ABOMEY

D o s s i e r

Abomey's value goes beyond its palaces, which are modest at best, and lies rather in its secular mixof religious and social powers forming a centre of gravity.

T H E F R A G I L EP A L A C E S A R E

C O N S T A N T LYB E I N G

R E B U I L T( P h o t o ©H O A - Q U I /M . H u e t ) .

They come, they see... and they leavesometimes disappointed, at least per-

plexed. “It doesn’t look authentic,” is a fre-quent comment from the 10,000 visitorswho, each year, visit Benin’s royal placesof Abomey, inscribed on UNESCO’s WorldHeritage List since 1985. Indeed the veryword “palace” implies ancient, luxuriousmaterials and majestic forms. And yet thebuildings are small with the biggest beinga simple rectangle 35 metres long. The wallsare of rammed earth, the corrugated ironroofs form an overhang supported by sim-ple wooden, sometimes concrete, pillars,masking the 130 polychrome bas-reliefs. Ofthe nine royal ensembles built by a dynastyof a dozen kings reigning from the begin-ning of the 16th century to the end of the19th century, many ruins are now lost in thebush, with only traces remaining of the im-pressive surrounding wall and the moat. Justa few modest buildings still stand, so fragilethat they have been constantly rebuilt, usu-ally with whatever materials were availableat the spur of the moment.

I N C A R N AT I N G T H E K I N G SThe wealth of the Abomey palaces is invis-ible. To fully appreciate them, one mustlook to the site’s geography and link thevalues of the full and empty spaces, or, inother words, the modest palaces and vastcourtyards. The former’s importance con-sisted essentially in the fact that they wereinaccessible to common people; whereasthe very size of the latter makes it easy toimagine the immense crowds gatheringthere to render homage to their king andmeasure the extent of his power.

Abomey reveals its riches only on thecondition that time is taken to discover itsprimary function: it was a centre of grav-ity, a symbol of religious and social pow-ers binding together the Fon ethnic group,the most numerous in Benin. The dadasi,princesses who each incarnate one of thedead kings, still live in a reserved area sub-ject to many taboos. Every four days, theroyal princesses leave food and drink at the12 tombs of the kings. In honouring thekings, an “average ceremony” lasting threeweeks is held once a year, while a “greatceremony”, which can last six months, isnormally staged every 10 years.

The frequency and splendour of theseceremonies depend entirely on the Admin-istrative Council of the Royal Families ofAbomey, which is also responsible for thesite’s upkeep, with the exception of themuseum section. In “civil society”, thesefamilies often have a modest statute, thuslimited financial means. It is, therefore, the

know-how, the work and money of tens ofthousands of the city’s inhabitants whokeep the miracle of Abomey alive. “No onewould refuse a contribution if the King re-quested it,” said Italian anthropologistGiovanna Antongini and architect GiovaniSpini, who visited the site on a UNESCO ex-pert mission in July 1995.

This is the case, day after day, not onlyfor the artisans and craftspeople restoringthe site, but also for the historians, musi-cians, dancers, soothsayers and religiousleaders who play the main role in carryingout all the related rituals: for they mustassume a function which their familieshave taken on for generations. Antonginidescribes, for instance, a man she calls the“guardian of emptiness”, who spends histime sitting on a chair to “control” a doorin the surrounding wall which today isnothing more than a ruin in the middle of afield. He does this because his family hasbeen doing so for generations.

It is the same secular mix of privilegeand power, of taboo and obligation, whichbinds the entire city. The convergence ofthese forces makes it possible for tradi-tional ceremonies to take place no matterwhat. By renewing and confirming the

site’s sanctity, it becomes a living place.Each person lives a double life: from thepeasant or craftsperson, at once a citizenof Benin, a cog in the machinery of a mod-ern economy, as well as a “subject” of the“king”, right down to the princes, endowedwith exceptional powers while yet work-ing as ordinary civil servants.

These relationships and their very mea-gre economic compensation are freely con-sented to. They are the results of a strongwill to maintain the historical identity in-carnated by the kings, manifested in a suc-cession of rites and ceremonies, and mate-rialized in the palaces which one youngman, interviewed by Antongini, describedas the “dossier of the people”.

This function necessitates a profoundreview of the traditional idea of conserva-tion. It calls for an anthropological ap-proach, resting at least as much on preser-vation of the intangible heritage as on themaintenance - in this case impossible - ofthe monuments. After all, compared withtheir symbolic force, just how important istheir appearance or of the materials usedfor their endless restoration?

There is, however, a red line whichmust never be crossed: the degradation ofmonuments should not be allowed to reacha point which prevents cultural and reli-gious practices from taking place. As theFon like to say, “wouldn’t you be ashamedto hold a ceremony in your father’s houseif it had been destroyed?”

René LEFORT

F O C U S

U N E S C O S 0 U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

D o s s i e r

THE UNIVERSAL‘S PASSIONAt Vézelay, “it's like ten men who love the same woman”. Trying to avoid this imbroglio, a localgroup turns to UNESCO in promoting the site as humanity's shared heritage.

V ézelay has been attracting peoplethroughout the millenaries - with

droves of Druids flocking to the healingforces of a pocket of seawater encrusted inthe hillside to the scores of pilgrims andcrusaders descending upon the basilica sup-posedly housing some of the divine remainsof Mary Magdalen.

Today Vézelay’s allure remains intact.Inscribed on the World Heritage List in1979, the village’s cobblestone streets ofgalleries and cafés have been spared theneon light of fast food joints and hotelchains afflicting so many tourist destina-tions of France’s Bourgogne region. Insearch of both culture and charm, some800,000 tourists come each year. And yet,“the average visit only lasts 20 minutes,”laments Agnès Millot of the local tourismoffice. “People rush through the village toquickly visit the basilica and then leave.The monks see more tourists than the wait-ers,” she says, which is dissappointing for“most of the town’s 500 residents, whoselivelihoods are linked to tourism.” Butwhile the trend of “travel marathons to seeas much as possible” is partly responsi-ble, Millot also sees local “resistance” in“adapting to these floods of people”.

History now seems to weigh againstVézelay, with residents unusually protec-tive of their beloved basilica, recalling les-sons learned in the religious wars of theMiddle Ages pitting villagers againstchurch authorities. The tension still sim-mers. About two years ago, monks of theLa Fraternité Monastique de Jérusalemrolled into town to oversee the spiritual andday-to-day running of the basilica with avehemence that offended most of the com-munity, prompting the bishop’s request forpublic pardon on their behalf. While thestorm subsided, the basilica remains asource of contention, with suspicion await-ing anyone tied to it.

One such target has been Presence atVézelay, a non-profit cultural associationwhose members love to show visitors thesites. “We have so many people coming hereon a quest for culture, but they’re not findingany response,” explains the directorBénédicte Guillon Verne. “So we’re trying

to create the tools to reveal Vézelay’sbeauty and unique identity.” Last year, thegroup led some 46,000 tourists, most ofwhom were referrals from Millot’s office,on 194 tours of the basilica and the village,in which they tried to get others involved,by visiting workshops and cafés. They alsoorganized “heritage classes” with presen-tations of Celtic, Roman and Gothic art andlocal crafts. Aside from a couple of poorlypaid staff members, the association relieson its volunteers.

But after two years of active work, theassociation remains a mystery. “Bénédicte,she’s sweet but I don’t know what her group

is about,” says a woman in a café who pre-fers not to give her name. The woman be-hind the counter also respects Verne buthighlights “Vézelay’s general rule: what wedon’t know, we don’t like.”

For Verne, this “porcupine-like situa-tion” is “ like ten men who love the samewoman”. But she sees a possible alterna-tive by working with another of Vézelay’sadmirers - the World Heritage Centre.“UNESCO is a way of avoiding noisy lo-cal interests,” says Verne, by getting peopleto see it as a unique site among others on theWorld Heritage List. The Centre and theassociation began recently collaborating

with a video on the site produced under theOrganization’s auspices and a soiree heldin March bringing local residents andgoods to Headquarters. The association isfinishing a “centre for cultural meditation”thanks in part to a cash prize awarded bythe Ford Foundation upon the Centre’s rec-ommendation. It’s the perfect location topromote the World Heritage List and “getresidents and visitors to see Vézelay ashumanity’s shared heritage”.

But this ‘sharing’ may not extend to reli-gious beliefs which might account for lo-cal skepticism concerning Verne’s group.The message of conversion is sculpted ontothe basilica’s walls with details which sheloves to point out. Looking up to the gar-goyles, she quietly asks if we wouldn’t pre-fer to enter the “light” by way of Jesus’outstretched hand at the entrance. Atten-tion is drawn to the sculpted Jews dressedas slaves, banned from entering the “gloryof God”, which she says “is not a judge-ment, but another path”.

The tour continues with the class ofsome 50 public school students between11 and 15, embarking on a mock pilgrim-age. Verne tells tales of the hardships fac-ing the pilgrims and crusaders in their“search for spiritual transformation”. Butshe fails to mention the crusade’s politicaland military objectives, which leavesJulian, 15, wondering. “It’s like in school,when the teacher tries to pass catechismoff as history. The best thing to do is notethe dates and forget the rest.”

Questions concerning Verne’s tales aremore forthcoming with a group of retiredengineers and their wives. As one womansays, “it’s always interesting to have a tourwith someone who believes in what they’resaying.” A point shared by Millot of thetourism office. “They give a tour which noone else can. They’re not working for asalary but out of their passion.”

This passion might be excessive andunsettling, but it is essential in giving lifeto the world’s heritage site - especiallythose with a religious dimension - fromBuddhist monestaries to sacred groves.

Amy OTCHET

M O C K “ P I L G R I M S ” A T T H E B A S I L I C A ’ SD O O R S ( P h o t o U N E S C O / A m y O T C H E T ) .

A Q U E S T F O R C U LT U R E

G A R G O Y L E S P E R C H E D A B O V E

Payment enclosed :❐ Cheque (except Eurocheques) ❐ Visa❐ Mastercard ❐ Eurocard❐ American Express ❐ Diners

Card No.: Expiration date:Date and signature

✄Subscription forms and payment (cheques to the order of Jean De Lannoy) should be sentto UNESCO Publishing’s subscription agent:

Jean De LannoyServices abonnementsAvenue du Roi, 202B-1190 Brussels (Belgium)

Tel: (32-2)538 51 69/538 43 08, Fax: (32-2)538 08 41.

Family name First name

Address

Postal code City Country

SUBSCRIPTION FORM

❐ 1 year 140 FF/£18/US$28 plus airmail charges:European Union countries: 64 FF/£8.15/US$13Other European countries: 72 FF/£9.15/US$14.65Other countries: 96 FF/£12.20/US$19.55

❐ 2 years 250 FF/£32/US$51 plus airmail charges:European Union countries: 128 FF/£16.30/US$26Other European countries: 144 FF/£18.30/US$29.30Other countries: 192 FF/£24.40/US$39.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

A new

magazine

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

○

A l l a r t i c l e s a r e f r e e o f c o p y r i g h tr e s t r i c t i o n s a n d c a n b e r e p r o d u c e d .

U N E S C O S O U R C E S

U N E S C O S O U R C E S N o . 8 0 / J U N E 1 9 9 6

P L A N E TE d u c a t i o n

18. . . . . .

A QUESTION OF PRIORITIESLatin America's education authorities want to concentrate on“what we really want, what we are doing, and what we can do.”

●

Ten yea r s t o t h e day a f t e r t h eCHERNOBYL nu c l ea r a c c i d en t , t h eca r i l l o n s i n mo re t han 500 c i t i e s andv i l l a ge s i n 40 c oun t r i e s r ang on 26 Ap r i li n memor y o f t h e c a t a s t r ophe ’s v i c t im s .A t 12 :00 l o c a l t ime , c hu r che s i n Ru s s i a ,Be l a ru s and Uk ra i ne t ook pa r t i n ac on ce r t un i t i ng f o r t h e f i r s t t imeca r i l l o n s i n a l l t h e wo r l d ’s c o r ne r s .T he e ven t , o r gan i z ed a s pa r t o f t h eUNESCO Che rnoby l P r og ramme , p r e c ededa “ s p i r i t ua l c on c e r t ” a t Pa r i s ’ No t r eDame Ca t hed ra l . A c onvoy o f F r en ch RedC ro s s t r u ck s t h en l e f t f o r Be l a ru s w i t hedu ca t i ona l ma t e r i a l s and t oy s f o r35 ,000 c h i l d r en .

▼

President of LITHUANIA, AlgirdasBrazauskas, and UNESCO’s Director-General, Federico Mayor, signed acooperation agreement on 22 May inVilnius. It notably calls for the creationof an international centre for distanceeducation in the capital city, assist-ance in developing a restoration andrelated funding plan for Vilnius’ OldCity and support for research institutesand professional media centres.

●