Berlin Wall, Nostalgia

-

Upload

kellhusofatrithau -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Berlin Wall, Nostalgia

-

7/31/2019 Berlin Wall, Nostalgia

1/3

Title:

Authors:

Source:

Document Type:

Full Text Word Count:ISSN:

Accession Number:

Database:

Record: 1

After the Berlin Wall, nostalgia for communism creeps back.

Jordan, Michael J.

Christian Science Monitor; 11/8/2009, p11, 1p

Article

92808827729

45081288

Academic Search Premier

Section: WORLD

After the Berlin Wall, nostalgia for communism creeps back

Dateline: PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC; AND PARTIZASKE, SLOVAKIA

In the airy lobby of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, George Santayana's

immortal words are a daily reminder to Czech staffers digitizing millions of Communist-era files:

"Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Yet even the institute's spokesman says his grandparents criticize the organization's mission.

They brush aside four decades of neighbors and co-workers spying on one another in the

former Czechoslovakia and long wistfully for a time of full employment.

"My grandmother says the Communists were great, while my grandfather says we're stupid to

open the archives, because people don't have jobs, which is more important than history,"

says Jiri Reichl.

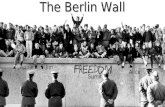

On the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germans and others across the world are

celebrating the moment that clinched the end of the cold war. But the Czech Republic reflects

another trend across Eastern Europe, 20 years into the traumatic shift from dictatorship to

democracy: creeping nostalgia.

Cold Wars end brought harsh competition

Each positive development of "democracy" ushered in negative consequences: Free-market

competition brought soaring prices and joblessness; free elections brought extremist parties;

free press brought incitement; free movement brought cross-border crime and westward "brain

drain."

This nostalgia is born of deep disillusionment with the present, says Libuse Valentova, a Czech

professor.

"People here admired the freedom and prosperity of the Western world," says Ms. Valentova,who tears up when recalling her time in the streets during the 1968 anti-Soviet revolt. "Now

what they see is materialism, corruption, inflation, lawlessness - and they can't find spiritual or

-

7/31/2019 Berlin Wall, Nostalgia

2/3

material prosperity."

Generations reared during Communism typically yearn for the days of free healthcare and

education, of more affordable goods and services. But they forget the years of deprivation,

poor-quality goods and services - and the climate of fear and severe censorship. Most

frustrating to them is the divide between those who could and couldn't adapt.

Take the city of Partizanske, in neighboring Slovakia. The vast Bata shoe factory, at its zenith,

employed 10,000 workers, produced 30 million pairs of shoes, and saw factory officials and

ruling Communists control every facet of work and social life.

"Here was 'Strong Bata' and 'Strong Socialism,' " says Partizanske's mayor, Jan Podmanicky.

"Families didn't have to struggle for anything, because the boss provided all their needs."

'When there's no work, no money, there's no happy life'

That was just fine by Julius Michnik, who arrived here in 1943 as a 15-year-old apprentice. He

attended mandatory morning exercise in the town square, then donned his uniform and headed

to the factory.

"If you worked hard, you made enough money; even enough to save some," says Mr. Michnik,

now president of the company's alumni association.

In time, he joined the party. "I was a Communist," says Michnik, who later had 1,500 workers

under him. "To be a director, you had to be. But I'm not ashamed. I never did anything bad to

anybody."

When the regime crumbled in 1989, so did the firm. Asian competitors meant that only a sliver

of the workforce remains.

"This is the hardest thing to learn about the new system: Things rise, things vanish," says the

mayor. "How do you teach people to be independent and take responsibility for themselves?

People from the outside can give you advice, but you have to change yourself."

Laid-off workers remind Michnik of what was lost. "Work, it's the most important thing," he says.

"I see all the unemployed here, spending their last cents in the bar around the corner. Whenthere's no work, no money, there's no happy life."

Unemployment: 14 percent

Back on the Czech side, Jan Klan is from the youth wing of the Communist Party of Bohemia

and Moravia, the third-largest parliamentary party.

Just 26, Mr. Klan is a Communist candidate for parliamentary elections next year. His

grandfather was a Communist, as was his mother, the local party official in their Bohemianvillage of Zabori nad Labem.

When the system disintegrated, some neighbors turned on her. "They blamed her for what the

-

7/31/2019 Berlin Wall, Nostalgia

3/3

Communists did," says her son.

Whereas the Communist era boasted "full employment," joblessness here is now 14 percent.

Drawn to Communist solutions, Klan joined the party in 2003.

In the old days, too, the party ordered Zabori nad Labem residents to regularly clean up their

village. They resented it, but the village stayed tidy. Today, no one is required to pick up litter or

tend to vegetation - and residents decry the slovenliness.

If elected, Klan says he would offer residents an economic incentive to clean up. But what if he

has no budget, or if they simply refuse? Would Communists revert to their brutal methods of the

past?

"We would want to change the mentality, that they should do it for the good of the village," he

says. "I know there were some mistakes in the past that we would want to avoid. It would be

against human rights to force someone to do something."

Mr. Reichl, of the Prague Institute, says such whitewashing - simply noting "mistakes" - drives

his colleagues to not only expose the regime's secrets, but "do PR for history," to puncture

nostalgia with public events, exhibits, and classroom education. "We don't want the younger

generations to forget," he says. "We want them to think about the history of their own family and

friends, and what actually happened during this period."

~~~~~~~~

By Michael J. Jordan, Correspondent

2009 The Christian Science Monitor (www.CSMonitor.com). Limited electronic copying and

printing is permitted under this license agreement. Copies are for personal use only. For re-use

and publication permissions, please contact [email protected].