BEETHOVEN - download.e-bookshelf.de · the first movement, b371, Beethoven had for-gotten to add...

Transcript of BEETHOVEN - download.e-bookshelf.de · the first movement, b371, Beethoven had for-gotten to add...

Edition EulenburgNo. 706

BEETHOVENPIANO CONCERTO No. 5

E� major/Es-Dur/Mi� majeurOp. 73

‘Emperor’

Eulenburg

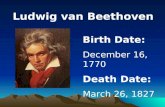

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Ernst Eulenburg LtdLondon · Mainz · Madrid · New York · Paris · Prague · Tokyo · Toronto · Zürich

PIANO CONCERTO No. 5E� major/Es-Dur/Mi� majeur

Op. 73‘Emperor’

Edited by/Herausgegeben vonPaul Badura-Skoda / Akira Imai

© 2010 Ernst Eulenburg & Co GmbH, Mainzfor Europe excluding the British Isles

Ernst Eulenburg Ltd, Londonfor all other countries

All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher:

Ernst Eulenburg Ltd48 Great Marlborough Street

London W1F 7BB

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . VVorwort . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . XITextual Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . XVIOssia Versions for Piano . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . XXI

I. Allegro . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1II. Adagio un poco mosso . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

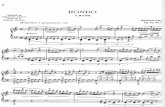

III. Rondo. Allegro ma non troppo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

CONTENTS

BE

ET

HO

VE

N’S

SY

MPH

ON

IC P

RO

DU

CT

ION

: CO

MPO

SIT

ION

, PE

RFO

RM

AN

CE

, PU

BL

ICA

TIO

NB

EE

TH

OV

EN

S SI

NFO

NIS

CH

ES

WE

RK

: DA

TE

N D

ER

EN

TST

EH

UN

G, U

RA

UFF

ÜH

RU

NG

, VE

RÖ

FFE

NT

LIC

HU

NG

Titl

e an

d ke

y/(P

relim

inar

y) p

rinc

ipal

Firs

t per

form

ance

/Fi

rst e

ditio

n/

Ded

icat

ion/

Tite

l und

Ton

art

date

s of

com

posi

tion/

Ura

uffü

hrun

gE

rsta

usga

beW

idm

ung

(Ent

wür

fe)

Hau

pt-

(as

orch

. Par

ts)

Kom

posi

tions

date

n

Op.

19Pi

ano

Con

cert

o N

o.2,

begu

n be

fore

179

3;29

Mar

ch 1

795

Lei

pzig

, 180

1C

arl N

ickl

as

B�

rev.

1794

, 179

8V

ienn

avo

n N

icke

lsbe

rg

Op.

15Pi

ano

Con

cert

o N

o.1,

18 D

ec 1

795

Bur

gthe

ater

, 2 A

pril

1800

Vie

nna,

180

1Fü

rstin

Bar

bara

Ode

scal

chi

CPr

ague

(geb

. Grä

fin v

on K

egle

vics

)

Op.

37Pi

ano

Con

cert

o N

o.3,

?180

05

Apr

il 18

03V

ienn

a, 1

804

Fürs

t Lou

is F

erdi

nand

CV

ienn

avo

n Pr

euße

n

Op.

56T

ripl

e C

once

rto,

C18

03–4

May

180

8V

ienn

a, 1

807

Fürs

t Fra

nz J

osep

hPf

te, V

ln, V

c, O

rch

Vie

nna

von

Lob

kow

itz

Op.

58Pi

ano

Con

cert

o N

o.4,

1805

–6M

arch

180

7V

ienn

a, 1

808

Erz

herz

og R

udol

phG

Vie

nna

von

Öst

erre

ich

Op.

61V

iolin

Con

cert

o, D

1806

23 D

ec 1

806

Vie

nna,

180

8St

epha

n vo

n B

reun

ing

Vie

nna

Lon

don,

181

0

Op.

73Pi

ano

Con

cert

o N

o.5,

1809

?28

Nov

181

1L

ondo

n, 1

810

Erz

herz

og R

udol

phE

� (‘Em

pero

r’)

Lei

pzig

Lei

pzig

, 181

1vo

n Ö

ster

reic

h

(Lis

t exc

lude

s fr

agm

ents

, inc

ompl

ete

wor

ks, a

nd s

oloi

stic

wor

ks n

ot ti

tled

‘Con

cert

o’/D

ie L

iste

bei

nhal

tet k

eine

Fra

gmen

te, u

nvol

lend

ete

Wer

ke o

der

solis

tisch

eSt

ücke

, die

nic

ht m

it “K

onze

rt”

betit

elt s

ind.

)

Beethoven composed the E flat major con-certo in 1809. It was published in Leipzig inFebruary 1811 by Breitkopf & Härtel, who alsoproduced an improved titled edition during thesame year. In November 1810, however, thefirm of Clementi & Co had already publishedthis concerto in London before the publicationof the first German edition. The work is dedi-cated to the Austrian Archduke Rudolph whowas Beethoven’s pupil, friend and patron.

The premiere took place at the seventh of theLeipzig Gewandhaus Concerts on 28 November1811 conducted by Johann Philipp Schulz (1773–1827) with Friedrich Schneider (1786–1853)as soloist and given an enthusiastic review bythe music critic Friedrich Rochlitz (1769–1842)in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung1. Thefirst performance in Vienna was on 12 February1812 by Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny (1791–1857), whose valuable comments regarding theperformance were published in Vol. 4 of his greatPiano Tutor, Op. 500.2 Ten years later CharlesNeate (1784–1877) gave the first performancein England. It was not, however, until the pe-riod 1830–1840 that the concerto, acclaimed asBeethoven’s greatest, was made popular byFranz Liszt (1811–1886) and Ferdinand Hiller(1811–1855). Theodore Döhler (1814–1856)was the first to perform the work in New Yorkin 1855.

The now commonly used title ‘EmperorConcerto’, possibly invented by Johann BaptistCramer (1771–1858), probably appeared inEngland during the 1840s, after Beethoven’sdeath in 1827. It has nothing to do with an em-peror, least of all Napoleon, of whose high-handed coronation Beethoven disapproved sostrongly that he withdrew the dedication fromthe ‘Eroica’ Symphony. Rather, the title refersto the generous conception, the majestic ‘im-

perial’ gesture, particularly in the first move-ment, and the triumphal character of both outermovements to which the almost religious,deeply emotional middle movement providesa strong contrast – a contrast not without itsown motivation. In the first movement the mosttender pianissimo counter-themes contrast withthe dense sonority of the main subject, and theB major key of the second movement is alsoanticipated, albeit in the enharmonic guise ofC flat major (bbl59 and 304ff.).

After the gentle fading away of the Adagio,the attacca of the third movement is a ‘coup dethéâtre’ which may still have a startling effecton some inattentive listeners today (couldHaydn’s ‘Surprise’ Symphony have been an in-fluence here?). It is also worth mentioning thatBeethoven’s ‘heroic period’ between 1803 and1809 seems to have come to an end with thisconcerto. Among the sketches there are entrieslike ‘Auf die Schlacht Jubelgesang’ (‘to the battle,song of jubilation’) and ‘Angriff – Sieg’ (‘attack,victory’). Here, and in earlier heroic works likethe Third and Fifth Symphonies, the ‘battle’concept appears in a sublimated form. Whilesoloist and orchestra confront each other morethan once in ‘fighting spirit’, this contrast isovercome and resolved in a sphere of exaltedharmony.

The historical aspect of Beethoven’s con-certos is summarized thus by Basil Deane:

Beethoven’s contribution to the concerto was of out-standing importance. He started with the Mozartianconcept of co-operative interplay between soloistand orchestra in the thematic presentation, adaptedit to his own particular kind of dramatic symphonicexpression, and finally made of the concerto a vehiclefor extreme virtuosity, without in any way detractingfrom its musical content or lessening the importanceof the orchestra. He arrived at a more open concep-tion of the first movement, with early participation ofthe soloist. He sought, and found, alternatives to the‘set-form’ slow movement. He related his movementsto each other, not only by linking passages between

PREFACE

1 Leipzig, XIX, 82 Carl Czerny, Vollständige theoretisch praktische Piano-

forte-Schule, Op.500, Part 4: Die Kunst des Vortrags(Wien, 1842), 114–116; (London: Cock, 1845), 112–114

movements but also by interrelated tonal events. Heleft a legacy which influenced profoundly, both forgood and bad, his l9th-century successors.3

The present edition of the Piano Concertoin E flat major represents a first attempt sinceBeethoven’s times at re-establishing the originaltext (Urtext) according to Beethoven’s inten-tions. Why, one may ask, were so many mistakesin the original edition, as well as in later printedscores based on this edition? The answer revealsan interesting aspect of the relations betweenBeethoven and his publishers.

During composition of the work the relationsbetween Beethoven and Breitkopf & Härtel inLeipzig (who were publishing his major works atthe time) were good, even friendly. Their col-laboration took the following form: Beethovenchecked the professionally prepared MS copiesof his works and then sent them to Leipzig,keeping the autographs in Vienna. In spite ofBeethoven’s repeated requests, the publishersnever let him have proofs and printed such worksrather quickly after they had been checked bythe publisher’s own proof-readers. Almost in-evitably this procedure led to mistakes in theoriginal editions that were never accepted byBeethoven without protest:

Meanwhile, herewith a generous portion of mistakes(regarding the Cello Sonata), to which my attentionwas drawn by a good friend because I can no longerbe bothered with what I have already written. I willarrange the compilation and printing of this list hereand have it announced in the papers, so that it can beobtained by all those who have already bought thework. This is further proof that, in my experience,what is printed from manuscripts written in my ownhand appears mostly correct in the engravings. Pre-sumably there will also be a number of mistakes inthe copy you have because, even if it is looked overby the author, he will no doubt overlook mistakes.(26 July 1809)

[…] regarding the very beautiful edition, I have toreproach you most emphatically: why is it not freefrom mistakes??? Why not first a copy for checkingfor which I have asked repeatedly? Mistakes tend to

creep into every copy but they can be corrected byany competent proof-reader […] I am somehowrather angry about that. (2 November 1809)

I have also found the following mistake in the Cminor Symphony, in the third movement in 3/4 time,when the major returns to the minor, and where itappears in the bass part as follows:

The two crossed out bars are two bars too many andmust be cut, of course also in all other parts whichhave rests. (21 August 1810)

Beethoven reminded Breitkopf of the samemistake on 15 October 1810, asking whetherthe two superfluous bars in the third movementof the symphony had been eliminated. ‘PerhapsI forgot to answer your letter, and therefore thebars might still be there.’

If Beethoven had not expressly demandedthis correction, these two superfluous and mu-sically pointless bars in the Fifth Symphonymight still be played today. They were indeednever cut in the edition of the parts, printed 15months earlier, and were included, in spite ofBeethoven’s two letters, in the score whichBreitkopf & Härtel published in 1826. The de-finitive correction was finally made by Mendels -sohn on the occasion of the Lower Rhine Mu-sical Festival in Aachen, 1846.4

In the [Fifth Piano] K [Concerto] there are rather alot of mistakes. (c. 2 May 1811)

Mistakes – mistakes! You yourself are nothing butone big mistake! I shall have to send you my copyist,I must come myself, if I don’t intend my works –published just as a mass of mistakes. The music tri-bunal in Leipzig does not apparently produce onesingle decent proof-reader, and you send the worksaway even before you have received the correctedproof.5 (6 May 1811)

VI

3 The Beethoven Companion/The Beethoven Reader, ed.D. Arnold and N. Fortune (London/New York, 1971),328

4 See A.W. Thayer, Ludwig van Beethovens Leben, rev. E.Forbes as Thayer’s Life of Beethoven (Princeton, 1964),Vol. 1, 500f.

5 A possible explanation for this seemingly inexplicablebehaviour of the publisher could be due to the postal con-ditions prevalent at the time; the sending and returning ofproof material would have resulted in a delay of twomonths in the publication of a work by Beethoven. Fur-

Beethoven’s list of corrections for the FifthPiano Concerto was rediscovered in 1983 atauction by Sotheby’s, London. This also ex-plains why Breitkopf & Härtel published a newedition relatively quickly. While it is not sub-stantially different in appearance (title-page,for instance), there are numerous correctionsin the piano part which were evidently madedirectly onto the plates.6 That only Beethovencould have made these corrections is evidentfrom the fact that many of those in the new edi-tion were based on the autograph score.

Of particular interest are corrections in thisnew edition at places where even the autographhas mistakes or inaccuracies. For instance, inthe first movement, b371, Beethoven had for-gotten to add in the score the sign for lifting thepedal, as well as the ottava sign in b465 whereit is musically necessary.

For quite some time Beethoven was unableto make up his mind regarding the tempo indi-cation for the third movement. The autographscore bears the indication ‘Rondo Allegro’, fol-lowed by the words ‘non tanto’, crossed out inpencil. This would explain why the tempo in-dication in the first edition is only ‘Allegro’.Beethoven’s final decision was, after all, for amore moderate tempo, hence the indication ‘al-legro ma non troppo’ in the corrected edition,and also in the Collected Works edition (c.1870).Because of lack of space, however, the words‘ma non troppo’ are printed in the second editionnot directly after the word ‘Allegro’ but closerto the ‘ff’ indication (‘fortissimo ma non troppo’would be contradictory). Since Beethoven wrotepedal indications between the two piano staves,the word ‘Pedal’ was often printed erroneouslyas ‘pia:’. This also happened in the new edition(and many later editions) as, for instance, in thefirst movement, bb162 and 420, and in the thirdmovement, b144. (The p in the third movementof many editions, bb402 and 404, is not shown

in any of the sources and does not make sense.The varied tutti, bb398–402, demands a f fol-lowed by a diminuendo.)

A comparison between the first and secondeditions of the original publication seems tosuggest that Beethoven corrected only the pianopart. This is a reasonable assumption if oneconsiders that correcting individual orchestralparts is a very laborious, time consuming task,and that Beethoven was mainly concerned withthe correct reproduction of the piano part. Thusit became more likely that various mistakes inthe orchestra were to remain uncorrected to thepresent time, as has been mentioned earlier. Al-though Wilhelm Altmann corrected a few errorsin his 1933 revision of this score, he unfortunatelyleft a great number of sometimes grave mistakesuntouched. What he described in his CriticalCommentary as ‘easier versions’ of the piano partare really no more than adjustments caused bythe limited range of many contemporary pianoswhich did not go beyond c′′′′. That even f′′′′wasnot high enough for Beethoven is proved bybb332–333 in the first movement. In this pas-sage Beethoven had originally taken the octavepassage up to the high g′′′′ but then crossed outthe last two of the high notes, presumably‘rather by necessity than by virtue’.

In the present edition the piano part is printedalso in the tutti passages, since this is the wayin which it appears in both the autograph andthe German first edition. Beethoven clearly dif-ferentiates between the large notes, and the smallcue notes which indicate the entries of the var-ious instruments. This kind of notation servedas a substitute for a full score at a time when thepublication of such scores, or versions for twopianos, had not become common practice. Sincethese notes in small print were surely not meantto be played, they are not reproduced in thepresent edition. With regard to the bass notesin large print, however, it can be assumed thatBeethoven intended, at least in this concerto,that the piano should participate in the tutti pas-sages by playing a kind of continuo part similarto those in Mozart’s piano concertos. The fol-lowing points are in support of this assumption:

VII

thermore, Breitkopf had to fear pirate editions, causedby indiscretion in Vienna, and that would have damagedhim considerably.

6 Piano concertos and symphonies were, at that time, usu-ally published in sets of parts; printed full scores wererare exceptions.

1. The bass (printed large) of the piano in the tutti pas-sages follows the bass of the strings except when thebass line is passed on to the viola or a wind instru-ment; in this case it is printed in small notes.2. The very careful figuring of the bass would hardlymake sense if it were not intended as an indicationactually to play with the orchestra; this is particu-larly evident in the numerous ‘tasto solo’ directionswhich are known to mean that only the bass line, andnot the chords, are to be played.

Nevertheless, there is as yet no definitiveanswer to the question whether a figured basswas, in Beethoven’s time, still realized in the tuttipassages of piano concertos. The fact that, dur-ing this period, a transition towards the modernpractice – a silent solo part in the tutti – hadbegun, is borne out by the first English editionwhich appeared before the original German

edition of the concerto. There, too, the bass notesare in bold print, and the cue notes are small.However, the figuring of the bass is omitted.7

Finally, we wish to extend our sincere thanksto the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PreußischerKulturbesitz, formerly the Deutsche Staatsbib-liothek, for allowing the repeated inspection ofBeethoven’s autograph MS, and for making amicrofilm available. We are equally grateful forthe assistance of the staff of the archive of theMusik-Abteilung of the Österreichische Na-tionalbibliothek, and of the Gesellschaft derMusikfreunde in Vienna.

Paul Badura-Skoda/Akira Imai Translation: Stefan de Haan

VIII

7 For a detailed discussion of performance practice for figuredbass in Beethoven’s piano concertos cf. ‘Beethoven’s BassoContinuo: Notation and Performance’ in Robin Stowelled., Performing Beethoven, Cambridge Studies in Per-formance Practice (Cambridge, 1994). (Review by Pauland Eva Badura-Skoda in Performance Practice Review,Vol. 10, No. 2, Madison Wisconsin, 1977.)

Editorial Notes

The present edition is believed to be the first inattempting to differentiate between staccatostrokes () and staccato dots (·), which in Beet -hoven’s autograph are distinct and presumablyintentionally so. His basso continuo indicationsin the solo part are also deliberate, and most ofthese are reproduced in the main text. There arenumerous ossia-versions in the solo part, par-ticularly in the highest ranges of the keyboard,and these were printed in the original editionsbecause many contemporary instruments didnot extend above c′′′′. The ossia are summa-rized in the report below. Today they are of lim-ited interest except when period instrumentsare used. The alterations necessarily made byBeethoven are worth mentioning since in someof them the notes are not just transposed downbut the lines are changed in an artful manner.

Principal Sources

AUT Autograph full score, Staatsbiblio-thek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kultur -besitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendels -sohn-Archiv, Berlin

1ED Piano first edition / engraving, Breit -kopf & Härtel, Leipzig, February1811, plate number 1613. The title-page reads: Grand / CONCERTO /Pour le Pianoforte / avec Accompa-gnement / de l’Orchestre / composéet dédié / à Son Altesse Imperiale /ROUDOLPHE / Archi-Duc d’Au-

triche etc. / par / L. v. Beethoven /Priorité des Editeurs / Ouev. 73 – Pr.4 Rthlr. / à Leipsic / Chez Breitkopf& Härtel. Copy in the Gesellschaftder Musikfreunde, Vienna.

2ED Piano second edition, based on firstengraving, plate number 1613 withcorrections specified by Beethoven;cf. preface. Copy in the National-bibliothek, Vienna.

ERRATA ‘Errata zum Es-Dur Konzert’ (Er-rata in the E flat major Concerto),Beethoven’s MS which probablywas part of his letter dated 6 May1811 to Breitkopf & Härtel inLeipzig. In this recently discovereddocument, which was sold by auc-tion in 1983, Beethoven correctedthe printing errors in the solo partof 1ED.

CLEM First English edition published byClementi & Co., London, November1810, just before 1ED. The title-pagereads: Grand Concerto / for the /PIANO FORTE / As newly con-structed / BY CLEMENTI & Co. /with additional Keys up to F. & alsoarranged for the Piano Forte up toC. / with Accompaniments for a /Full Orchestra / COMPOSED BY /Lewis van Beethoven / Op. 64 [sic!]/ London, Printed by Clementi &Compy. 26, Cheapside

IX

Beethoven komponierte das Es-Dur Klavier-konzert im Jahr 1809. Es erschien im Februar1811 bei Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig, undnoch im gleichen Jahr daselbst in einer verbes-serten Titelauflage. Doch noch früher als diedeutsche Erstausgabe erschien dieses Konzertin London beim Verlag Clementi & Co., nämlichim November 1810. Das Werk ist BeethovensSchüler, Freund und Gönner, dem ErzherzogRudolph von Österreich gewidmet.

Die erste Aufführung erfolgte am 28. No-vember 1811 im siebten Gewandhauskonzertin Leipzig durch Friedrich Schneider (1786–1853) unter der Leitung von Johann PhilippSchulz (1773–1827) und fand eine begeisterteKritik von Rochlitz (1769–1842) in der Allge-meinen musikalischen Zeitung1. Die erste Wie-ner Aufführung erfolgte etwas später, am 12.Februar 1812 durch Beethovens Schüler CarlCzerny (1791–1857), der später im vierten Bandseiner großen Klavierschule op. 5002 wertvolleHinweise zur Aufführung veröffentlichte. Dieerste englische Aufführung erfolgte 10 Jahrespäter durch Charles Neate (1784–1877). Docherst 1830-1840 wurde dieses größte Klavier-konzert Beethovens durch Franz Liszt (1811–1886) und Ferdinand Hiller (1811–1855) po-pulär. In New York wurde es erst 1855 durchTheodor Döhler (1814–1856) zum ersten Malaufgeführt.

Der heute übliche Titel „Emperor Concerto“kam erst nach Beethovens Tod (1827) in Umlaufund dürfte in den 40er Jahren des 19. Jahrhun-derts in England aufgekommen sein, möglicher -weise durch Johann Baptist Cramer (1771–1858).Er hat nichts mit einem Kaiser zu tun, schon garnicht mit Napoleon, dessen selbst arrangierteKaiserkrönung Beethoven so missfiel, dass er die

Widmung der „Eroica“-Symphonie rückgängigmachte. Der Titel bezieht sich vielmehr auf dieGröße der Konzeption, die majestätische „im-periale“ Geste, speziell im I. Satz, und den tri-umphalen Charakter der Ecksätze, zu denen derquasi religiöse verinnerlichte Mittelsatz einenstarken Kontrast bildet. Dieser Gegensatz er-scheint aber nicht unmotiviert. Schon im I. Satzfinden sich neben den Klangballungen des Haupt -themas zarteste Gegenthemen im Pianissimo, unddie Tonart H-Dur des II. Satzes wird schon imI. Satz durch die (enharmonisch gleichen) Ces-Dur-Stellen T. 159 und 304 ff. vorbereitet.

Der plötzliche Beginn des III. Satzes nachdem zartesten Verklingen des Adagio ist ein„Coup de théâtre“, der auch heute noch manchenverschlafenen Zuhörer aufschrecken lässt. (Obda Haydns „Surprise Symphony“ Pate gestan-den hat?) Bemerkenswert ist noch, dass diesesKonzert Beethovens „heroische Periode“ derJahre 1803-1809 abzuschließen scheint. Zwi-schen den Skizzen finden sich Eintragungen wie„Auf die Schlacht Jubelgesang“, „Angriff –Sieg“. Freilich ist ebenso wie in den vorherge-henden heroischen Werken wie der 3. oder 5.Symphonie die Idee des Kampfes sublimiert.Wenn Solist und Orchester auch mehr als ein-mal „kämpferisch“ einander gegenübertreten,so wird dieser Gegensatz doch in einer höherenHarmonie überwunden und aufgelöst.

Sehr schön schreibt Basil Deane über diehistorische Stellung der Beethoven-Konzerte:

Beethovens Beitrag zum Konzert war von höchsterBedeutung. Er begann mit dem Mozartischen Konzepteines zusammenwirkenden Wechselspiels zwischenSolist und Orchester in der thematischen Darstellung,eignet sich das Konzert in seiner eigenen Art desdramatischen und symphonischen Ausdrucks an,und macht es schließlich zu einem Träger äußersterVirtuosität, ohne jedoch dabei von seinem musika-lischen Inhalt abzulenken oder die Bedeutung desOrchesters zu verändern. Er erreichte ein offeneresKonzept des I. Satzes, bei dem der Solist früher ein-treten konnte. Er suchte und fand Alternativen zur

VORWORT

1 Leipzig, XIX, S. 8.2 Carl Czerny, Vollständige theoretisch praktische Piano-

forte-Schule, op. 500, Part 4: Die Kunst des Vortrags,Wien 1842, S. 114–116. Auch in: Carl Czerny, Über denrichtigen Vortrag der sämtlichen Beethovenschen Klavier -werke, P. Badura-Skoda (Hrsg.), Wien 1963, S. 106.

festgelegten Form des langsamen Satzes und er ver-knüpfte Sätze miteinander, nicht nur durch verbin-dende Motive, sondern auch durch tonale Verwandt-schaften. Er hinterließ so ein Erbe, das im Guten wieim Schlechten seine Nachfolger im 19. Jahrhunderttief beeinflusste.3

Die vorliegende Ausgabe des Es-Dur Kla-vierkonzerts unternimmt den Versuch, zum ers-ten Mal seit Beethovens Zeiten den Urtext imSinne Beethovens wiederherzustellen. Wie wares eigentlich zu den Fehlern in der Original-ausgabe und in den darauf fußenden späterenPartiturdrucken gekommen? Die Antwort aufdiese Frage wirft ein interessantes Licht aufBeethovens Verhältnis zu seinen Verlegern.

Zur Zeit der Komposition dieses Werkesstand Beethoven in guter, nahezu freundschaft-licher Beziehung zum Leipziger VerlagshausBreitkopf & Härtel, das damals seine wichtigs-ten Werke veröffentlichte. Die Zusammenar-beit vollzog sich so, dass Beethoven von ihmselbst überprüfte Abschriften seiner Werkenach Leipzig sandte und seine Autographe inWien behielt. Trotz wiederholter MahnungenBeethovens schickte der Verleger ihm keineKorrekturabzüge, sondern brachte die Werkenach Lesung einer Hauskorrektur ziemlichschnell im Druck heraus. Dieses Verfahrenmusste fast zwangsläufig zu Fehlern in denOriginal-Ausgaben führen, die Beethoven kei-neswegs stillschweigend hinnahm:

Hier eine gute Portion Druckfehler, auf die ich, daich mich mein Leben nicht mehr bekümmere umdas, was ich schon geschrieben habe, durch einenguten Freund von mir aufmerksam gemacht wurde(nämlich in der Violoncell-Sonate). Ich lasse hierdieses Verzeichnis schreiben und drucken und in derZeitung ankündigen, daß alle diejenigen, welche sieschon gekauft, dieses holen können. Dieses bringt michwieder auf die Bestätigung der von mir gemachtenErfahrung, daß nach meinen von meiner eigenenHandschrift geschriebenen Sachen am richtigstengestochen wird. Vermutlich dürften sich auch in derAbschrift, die Sie haben, manche Fehler finden; aber

bei dem Übersehen übersieht wirklich der Verfasserdie Fehler. (26. Juli 1809)

[…] ich mache Ihnen recht lebhafte Vorwürfe, warumdie sehr schöne Auflage nicht ohne Inkorrektheit???Warum nicht erst ein Exemplar zur Übersicht, wie ichschon oft verlangte? In jede Abschrift schleichen sichFehler ein, die aber ein jeder geschickte Korrektor[beim Verlag, Anm. d. Verf.] verbessern kann […]Etwas sehr ärgerlich bin ich deswegen. (2. November1809)

Folgende Fehler habe ich noch in der Sinfonie aus Cmoll gefunden, nämlich im 3ten Stück im 3/4 Takt,wo nach dem dur wieder das moll eintritt, stehtso: ich nehme gleich die Baßstimme, nämlich:

Die zwei Takte, worüber das x ist, sind zu viel undmüssen ausgestrichen werden, versteht sich auch inallen übrigen Stimmen, die pausieren. (21. August1810)

Am 15. Oktober 1810 erinnerte BeethovenBreitkopf an denselben Fehler und fragte, obdie beiden überzähligen Takte im III. Satz derSymphonie schon ausgeschieden seien. „Viel-leicht vergaß ich, Ihnen zu antworten, und dieTakte könnten noch da sein.“

Hätte Beethoven diese Korrektur nicht aus-drücklich verlangt, so würde die 5. Symphoniewohl noch heute mit diesen zwei überzähligen,musikalisch unsinnigen Takten erklingen. Siewurden nämlich in der eineinviertel Jahre vor-her gedruckten Stimmenausgabe nicht nach-träglich ausgemerzt und sind trotz der beidenBriefe Beethovens in die bei Breitkopf & Härtel1826 erschienene Partitur aufgenommen wor-den. Die endgültige Richtigstellung erfolgteerst 1846 durch Mendelssohn anlässlich desNiederrheinischen Musikfestes in Aachen.4

Im [5. Klavier-] K[onzert] sind ziemlich viele Feh-ler. (ca. 2. Mai 1811)

Fehler – Fehler! Sie sind selbst ein einziger Fehler!Da muß ich meinen Copisten hinschicken, dort muß

4 Vgl. A. W. Thayer, Ludwig van Beethovens Leben, über-setzt v. H. Deiters, hrsg. v. H. Rieman, Bd. 1, Leipzig3–51923, S. 95f.

XII

3 In: D. Arnold und N. Fortune (Hrsg.), The BeethovenCompanion/The Beethoven Reader, London/New York1971, S. 328.

ich selbst hin, wenn ich will, daß meine Werke –nicht als bloße Fehler erscheinen. Das Musik-Tribunalin Leipzig bringt, wie es scheint, nicht einen einzigenordentlichen Korrektor hervor; dabei schicken Sie,noch ehe sie die Korrektur erhalten die Werke ab.5

(6. Mai 1811)

Erst 1983 ist Beethovens Korrekturliste zum5. Klavierkonzert bei einer Versteigerung imAuktionshaus Sotheby in London aufgetaucht.So ist es erklärlich, dass Breitkopf & Härtel re-lativ bald eine Neuauflage herausbrachte, diesich zwar äußerlich (z. B. im Titelblatt) nichtvon der fehlerhaften ersten Auflage der Original -ausgabe unterschied, jedoch im Klavierpart zahl -reiche Korrekturen aufwies, die offensichtlichin den Stichplatten vorgenommen wurden.6 Dassder Urheber dieser Korrekturen nur Beethovenselbst sein konnte, erkennt man daran, dass dieNeuauflage an vielen Stellen im Sinne des Par-titurautographs verbessert wurde.

Von besonderem Interesse sind die Verbes-serungen dieser Neuauflage an jenen Stellen,wo selbst das Autograph fehlerhaft oder unge-nau ist. So hatte Beethoven im I. Satz das Pedal -aufhebungszeichen in T. 371 versehentlich nichtin der Partitur notiert und in T. 465 das musika-lisch notwendige 8va-Zeichen niederzuschreibenvergessen.

Beim Beginn des III. Satzes hat Beethovenlängere Zeit in Bezug auf die Tempobezeich-nungen geschwankt: Im Partiturautograph steht„Rondo Allegro“, dahinter die Worte „nontanto“, mit Bleistift durchgestrichen. Die ersteAusgabe hat deshalb als Tempoangabe bloß„Allegro“. Schließlich entschied Beethoven sichdoch für ein gemäßigtes Tempo und ließ in denverbesserten Auflagen die Bezeichnung „allegroma non troppo“ drucken, die auch von der spä-

teren Gesamtausgabe übernommen wurde. AusRaummangel stehen die Worte „ma non troppo“in der 2. Auflage übrigens nicht direkt hinterdem Wort „Allegro“, sondern näher an der Be-zeichnung ff (Ein „fortissimo ma non troppo“wäre aber widersinnig). Da Beethoven seinePedalbezeichnungen zwischen den beiden Sys-temen zu notieren pflegte, wurde so manches„Pedal“ irrtümlich als „pia:“ wiedergegeben,auch in der Neuauflage und vielen späterenAusgaben. Dies bezieht sich u. a. auf den I.Satz T. 162, T. 420 und auf den III. Satz T. 144.(Das in vielen Ausgaben stehende p im III. SatzT. 402 und 404 steht überhaupt in keiner Quelleund ist sinnwidrig: Die variierte Wiederholungdes Tutti T. 398–402 erfordert ein f mit nach-folgendem diminuendo.)

Wie der Vergleich der 1. und 2. Auflage derOriginalausgabe zeigt, scheint Beethoven nurdie Klavierstimme korrigiert zu haben. Dies istverständlich, wenn man bedenkt, dass das Ver-bessern einzelner Orchesterstimmen äußerstmühsam und zeitraubend ist, und dass es Beet-hoven vor allem auf eine korrekte Wiedergabedes Soloparts ankam. – So kam es eher dazu,dass mehrere Fehler im Orchester bis zum heu-tigen Tag unkorrigiert geblieben waren, wieeingangs bemerkt wurde. Zwar hat WilhelmAltmann bei seiner Revision dieser Partitur1933 einige wenige Stellen verbessert, jedochleider eine ganze Anzahl zum Teil gravierenderFehler stehengelassen. Was er im Revisionsbe-richt als „Erleichterungen“ der Klavierstimmebezeichnet, waren in Wirklichkeit Anpassungenan den beschränkten Tonumfang vieler damali-ger Klaviere, die nicht über das viergestrichenec hinausgingen. Dass Beethoven selbst das vier -gestrichene f als Spitzenton nicht genügte, zeigtT. 332–333 des I. Satzes. Hier hatte Beethovenden Oktavenzug in seiner Partitur ursprünglichbis zum hohen g (4) geführt. Da aber kein Kla-vierinstrument der damaligen Zeit über diesenTonumfang verfügte, strich er die beiden letztenhohen Noten wieder durch, sicherlich „aus derNot und nicht aus Tugend“.

Erstmalig wird in dieser Ausgabe die Kla-vierstimme auch während der Tutti nach dem

5 Für dieses (uns) heute unerklärlich scheinende Verhaltendes Verlegers gibt es folgende mögliche Erklärung: Beiden damaligen Postverhältnissen hätte das Hin- und Zu-rückschicken von Korrekturexemplaren mindestens zueiner zweimonatigen Verzögerung der Herausgabe einesBeethovenschen Werkes geführt. Vor allem aber mussteBreitkopf befürchten, dass dann durch Indiskretion inWien Raubdrucke entstehen könnten, durch die sein Ver-lag empfindlich geschädigt worden wäre.

6 Bekanntlich erschienen damals Klavierkonzerte undSymphonien gewöhnlich in Einzelstimmen; Partiturdru-cke waren eine seltene Ausnahme.

XIII

bekanntlich bedeuten, dass an solchen Stellen nurdie Basslinie, aber keine Akkorde zu spielen sind.

Trotzdem ist die Frage, inwieweit zu Beet-hovens Zeiten noch Generalbass während derTutti in den Klavierkonzerten gespielt wurde,nicht eindeutig zu lösen. Dass sich in diese Periode ein Übergang zur modernen Praxis –Schweigen des Soloparts während der Tutti –anbahnte, zeigt die englische Erstausgabe des5. Klavierkonzertes, die sogar noch vor derdeutschen Originalausgabe erschien. Auch dortsind die Bassnoten groß und die Stichnotenklein gedruckt, die Generalbassbezifferung istaber weggefallen.7

Abschließend möchten wir der Staatsbi-bliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz(früher Deutsche Staatsbibliothek) für die wie-derholte Einsichtnahme in Beethovens Auto-graph und für die Zur-Verfügung-Stellung einesMikrofilms herzlich danken. Ebenso herzlichsei dem Personal der Musik-Abteilung derÖsterreichischen Nationalbibliothek und desArchivs der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde inWien gedankt.

Paul Badura-Skoda/Akira Imai

Autograph und der deutschen Erstausgabe wie-dergegeben. Beethoven unterscheidet darin deut-lich zwischen den groß geschriebenen bzw. ge-druckten Bassnoten und den kleinen Stichnoten,welche die Einsätze der verschiedenen Instru-mente anzeigen. Diese Art der Notierung dienteals Partiturersatz in einer Zeit, als es noch nichtüblich war, Partituren oder zweiklavierige Aus-gaben von Klavierkonzerten zu drucken. Da dieseklein gedruckten Noten sicherlich nicht mitzu-spielen sind, wurden sie in der vorliegendenAusgabe weggelassen. Anders steht es hingegenmit der Generalbassbezifferung. Es besteht allerGrund anzunehmen, dass Beethoven zumindestin diesem Konzert mit einem generalbassartigenMitspielen des Klavierparts während der Tuttirechnete, ähnlich, wie es bei den Mozart-Kla-vierkonzerten der Fall war. Folgende Gründesprechen für diese Annahme:

1. Die (groß notierten) Klavierbässe im Tutti gehen mitden Streicherbässen konform, schweigen aber, wenndie Basslinie auf die Viola oder ein Blasinstrumentübergeht; sie werden dann klein notiert.2. Die sehr sorgfältige Bezifferung ergäbe kaum einenSinn, wenn sie nicht zum tatsächlichen Mitspielennotiert worden wäre; dies zeigt sich insbesonderebei den zahlreichen „tasto solo“-Notierungen, welche

XIV

7 Die Generalbasspraxis wird ausführlich von Tibor Szaszerläutert in seinem Aufsatz „Beethoven’s Basso Continuo:Notation and Performance“ in: Robin Stowell (Hrsg.),Performing Beethoven, Cambridge Studies in PerformancePractice, Cambridge 1994. (Aufsatz rezensiert von Paulund Eva Badura-Skoda in: Performance Practice Review,Vol. 10, No. 2, Madison Wisconsin 1977.)

Revisionsbericht

Es wurde in der vorliegenden Ausgabe erstmalsversucht, den Unterschied zwischen Staccato-Keilen () und Staccato Punkten (·) wiederzuge-ben, die Beethoven wohl mit Absicht im Auto-graph eintrug. Beabsichtigt waren von ihmauch die „basso continuo“-Eintragungen fürden Solopart (siehe Vorwort); sie sind größten-teils im Haupttext wiedergegeben. Ferner dievielen Ossia-Versionen für Klavier in den be-sonders hohen Lagen, die in den Originalaus-gaben abgedruckt sind, einfach weil der Ton-umfang vieler Instrumente der damaligen Zeitnur bis c4 reichte. Sie sind im Anschluss im de-taillierten Revisionsbericht zusammengefasstdargestellt. Solche aus technischen Gründennotwendigen Abweichungen sind für uns heuteweniger interessant, es sei denn man spielt aufhistorischen Instrumenten. Hierfür notwendigeÄnderungen Beethovens sind künstlerisch er-wähnenswert, denn bei manchen wurden nichtnur die Töne einfach tiefer gesetzt, sondern diemusikalischen Linien sind ausgeklügelt geän-dert worden.

Hauptquellen

AUT Partitur-Autograph, Staatsbiblio-thek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kul-turbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Men-delssohn-Archiv, Berlin

1ED Erster Stich der Klavierpartitur inOriginalausgabe, Breitkopf & Här-tel in Leipzig, Februar 1811 Plat-tennummer 1613 mit der folgendenTitelseite: Grand / CONCERTO /Pour le Pianoforte / avec Accompa-

gnement / de l’Orchestre / composéet dédié / à Son Altesse Imperiale /ROUDOLPHE / Archi-Duc d’ Au-triche etc. / par / L. v. Beethoven /Priorité des Editeurs / Ouev.73 – Pr.4 Rthlr. / à Leipsic / Chez Breitkopf& Härtel. Gesellschaft der Musik-freunde, Wien

2ED Zweite Auflage der Originalaus-gabe mit den von Beethoven veran-lassten Stichkorrekturen in den Plat-ten (Plattennr. 1613); siehe Vor-wort. Nationalbibliothek Wien

ERRATA „Errata zum Es-Dur Konzert“, auto -graphes Manuskript, welches höchst -wahrscheinlich zu Beethovens Briefvom 6. Mai 1811 an Breitkopf &Härtel in Leipzig gehört. In diesem1983 zur Auktion gekommenen, neuentdeckten Dokument verbesserteBeethoven die Stichfehler in derSolostimme in 1ED, siehe Vorwort.

CLEM Englische Erstausgabe, 1810 vonClementi & Co. in London kurz vorlED veröffentlicht. Die Titelseitelautet: Grand Concerto / for thePIANO FORTE / As newly con-structed / BY CLEMENTI & Co. /with additional Keys up to F. & alsoarranged for the Piano Forte up toC. / with Accompaniments for a /Full Orchestra / COMPOSED BY/ Lewis van Beethoven / Op. 64 [sic!]/ London, Printed by Clementi &Compy. 26, Cheapside

XV

XVI

Textual Notes

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

Ossia Versions for Piano

XXII