Assemblage - Imperfect Utopia (Kruger)

-

Upload

empyrean79 -

Category

Documents

-

view

56 -

download

4

description

Transcript of Assemblage - Imperfect Utopia (Kruger)

Imperfect Utopia / Un-Occupied TerritoryAuthor(s): Laurie Hawkinson, Barbara Kruger, Nicholas Quennell, Henry Smith-Miller, StanleyAllen, Mark WigleySource: Assemblage, No. 10 (Dec., 1989), pp. 19-45Published by: The MIT PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3171141Accessed: 07/09/2009 15:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with thescholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform thatpromotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Assemblage.

http://www.jstor.org

Hawkinson, Kruger, Quennell, Smith-Miller

Imperfect Utopia /

Un-Occupied Territory

0

Aw

.. ....... .... . .. ..............

............~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: :: ::::: ... .................: :: :: :::::.:.:: ::.:.::::.::.:::......::.:.:::::.::.:::::

The Theory

To disperse the univocality of a "Master Plan" into an aerosol of

imaginary conversations and

inclusionary tactics.

To bring in rather than leave out.

To make signs. To re-naturalize.

To question the priorities of style and taste.

E To anticipate change and invite alteration.

To construct a cycle of repair and

discovery. To question the limitations of vocation.

To be brought down to earth.

To make the permanent temporary. To see the forest for the trees.

To have no end in sight.

U

a)Iam., .

S ,i o'^

06r i 'e, a

F, *s S a

Noi I I (0 (U

5 o

.6 c

Zoiib

i0s

s ft E *5f a

(U ae)

( U

*a ) 0 0

I, O ^1 I

is M h.

Im

0

(U(

0) a)3

'ii

(A Q) (Oa

Imcr

SI

(U

a)

? _w ^

r 1^^

-^e

: S

*1

i^ t *t,* ?t

_ ~ ~ r ..

PEi I

.. ..y

The collaborative work of Hawkinson, Kruger, Quen- nel, and Smith-Miller sets out to dismantle dominant categories of production, conception, and criticism established within architectural practice. This is accom- plished by a twofold process. On the one hand, by expanding the architectural field to encompass land- scape design, art, and engineering, they begin to rewrite the inherited notion of "program" to suggest alternative scenarios of planning and realization. Architecture's relationship to institutional and ideological structures, and its means of realization and legitimation are called into question. The idea of a "master plan," with all its attendant associations - an overarching, distant, per- fectly realized and finished plan, admitting no dissent, no contingency - is rejected. On the other hand, by questioning the status of the architectural object and rethinking some of the conceptual oppositions that have organized contemporary architectural discourse - such as nature/culture, subject/object, inside/outside- these projects suggest the possibility of a more thoroughgoing critique of architecture as a commodity within an econ- omy of desire and dispersion. And both projects pre- sented here engage the kind of posturban artificial landscape that has come to dominate the present-day reality and that architects have by and large chosen to ignore.

This attempt - both the rewriting of the program as a series of strategies and scenarios, and the formal disper- sion that characterizes these productions - owes an obvious debt to the ideas of Bernard Tschumi and of Rem Koolhaus and OMA. Tschumi's assertion that "there is no architecture without the event" as well as his links to the New York art scene in the mid- to late seventies (a scene that included Kruger), his fascination with language, graphics, and advertising, all seem to sanction the notion of an expanded field of architectural intervention at work here. And Koolhaus's recent series of projects for the suburban landscape parallel many of the innovations at a formal and procedural level. By choosing to elaborate the research programs mapped out by Tschumi, Koolhaus, and others, Hawkinson, Kruger,

Quennell, and Smith-Miller have insisted on the importance of a critical discourse that questions the dis- ciplinary limits of architecture simultaneously from within and without.

In the project begun in 1987 for the North Carolina Museum of Art, "Imperfect Utopia: A Park for the New World," Hawkinson, Kruger, Quennell, and Smith- Miller substitute an open-ended series of planning scen- arios for the traditional master plan. The convention of zoning as a prototypical method to organize suburban interventions is appropriated and reworked in a new context as a flexible tool, capable of accommodating change, rather than to lay down inflexible guidelines. Intervention is dispersed over the site and realized incre- mentally. The team engages the history of the site, including the existing mid-seventies museum designed by the office of Edward Durrell Stone, through recon- structed traces, references to indigenous plantings and patterns of occupation. They interpret the idea of "place" broadly, deploying the devices that encode loca- tion - historic markers, signs, and pathways - in an ironic manner. The notion of a distinct realm for "pure art" is contaminated by an invasion of the everyday: their conceptual planning framework would accommo- date the existing prison and suburban housing, picnic areas, ornamental ponds, paths, and signs alongside tra- ditional art objects in the landscape.

The more recent project for the Los Angeles Arts Park Center, "Un-Occupied Territory: An Economic Ecol- ogy," is also structured around an intervention in the landscape. Responding critically to the site plan as received from an earlier design by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and to the corresponding sectioning off of the site proposed by the organizers of the competition, Hawkinson, Kruger, Quennell, and Smith-Miller began by proposing a different pattern for the occupation of the territory. By reinscribing onto the site the topo- graphic boundary that marks the hundred-year flood- plain, they established an (artificially) "natural" line of demarcation with which to organize the site. Land

24

below this line remains uncultivated, that is to say, it is allowed to revert to the condition of the indigenous cha- parral. Above this line is the cultivated zone, in which all building is concentrated. The proposal consolidates all of the building into a single open structure - a hybrid of a shopping mall and the traditional hispanic mercado - which could be expanded incrementally and occupied by diverse users. Embedded in the inevitable parking lot is the Museum of Un-Natural History, a new program element proposed by the team in a con- scious reference to the spiral form of Le Corbusier's Museum of Unlimited Growth of 1931. More than a

knowing historical reference, this quotation serves to locate the ambitions of the project: the linear, serial form of the museum as a record of historical and tech- nological progress turned back upon itself to create a traditional "place" as both a continuation and a criti- cism of the modernist project.

The discussion that follows took place in New York among Laurie Hawkinson, who teaches at Columbia University and has an architectural practice with Smith- Miller in New York City; Barbara Kruger, an artist who works with pictures and words; Nicholas Quennell, a landscape architect who practices in New York City with his firm Quennell Rothschild Associates; Henry Smith-Miller, an architect involved with both theory and practice; Stanley Allen, an architect working in New York City; Beatriz Colomina, who teaches archi- tectural history at Princeton University and is currently a fellow of the Chicago Institute for Architecture and Urbanism; and Mark Wigley, who teaches architectural theory at Princeton University and is also a CIAU fellow.

In the discussion, issues involving the usefulness of crit- ical strategies borrowed from the art world, architec- ture's resistance to strategies of displacement, the disciplinary context of the architectural competition, the cultural realm of the museum and the gallery, and the different ways in which art and architecture fold them- selves into these institutional structures, as well as popu-

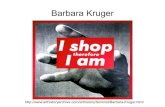

lar culture in the form of the suburban development or the shopping mall, all emerge as themes with which to evaluate and situate this attempt to rewrite "program" and to subject disciplinary boundaries to critical scru- tiny. The fundamental assumptions of the projects already supply an autocritique that the discussion elabo- rates and extends. This work forces an entry into the difficult territory of popular culture and appropriates the restless gaze of the consumer as a contemporary para- digm of architectural perception. But we are compelled to continue to ask what mechanisms of resistance, in an architectural culture increasingly dominated by the tran- sient image, prevent these projects, and even their pub- lication in this journal, from entering into the relentless cycles of consumption and commodification, a "shop- ping mentality," in which, to quote Kruger, "the acts of looking and using are dissolved by the lure of selection."

BC: In an airplane nightmare this morning coming from Chicago, after changing planes for the third time due to mechanical problems, we ended up sitting next to this guy whom I had spotted earlier in the morning because he was somehow too sharply dressed and carry- ing one of these big, black art portfolios as he paced up and down. And in my boredom I had fantasized about what would be inside - drugs, classified papers, some-

thing illegal, no doubt. He must have been equally bored, because now that we had settled in this plane that finally took off, and unpacked the material that you had sent us for this interview, he began surreptitiously reading your documents over our shoulders. And then he tentatively asked, "Is this a project for a sculpture park?"

BK: Oh, no!

BC: Exactly. We said no, it is a collaborative project between some architects, a landscape designer, and an artist. "Ah!" he said, looking at the cover where there is this picture of the landscape crossed over with blocks of

type, "I thought I recognized the artist in the typogra-

25

I

assemblage 10

phy. 'Imperfect Utopia,' that sounds very much like Barbara Kruger. But I don't know about 'A Park for the New World.' I mean, it's too literal, isn't it? But I guess that's where architecture comes in, right?"

BK: But who is this guy?

BC: Well, he turned out to be a gallery dealer from Philadelphia. He could understand Barbara's involve- ment in this project in as much as it was for an art museum. It seemed natural to him that she could place a work inside the museum in the gallery, or outside the museum in the grounds, but not that she could be involved in the museum itself, in the very definition of its interior and exterior.

BK: So it's a conflation of two issues: the categorizing mania that is driven to name and contain practices this is Art, this is Architecture, this is Literature, this is Theory - and the stereotype of the artist as a kind of kooky mediator between God and the public. Laurie and Henry aren't just the sum of their T-squares or Nicholas his landscaping gear or me my beret. It's been a pleasure for us to displace these cliches through our rendition of a "collaboration" that is a fluid process rather than an object.

BC: The thing about this stereotype is that it presup- poses a conventional art, an art that does not question its frame, whether that be the institutional mechanisms of the art world or of the architecture in which it is exhibited. Clearly, Barbara's work does the former. And the question raised by this collaboration and these two projects is to what extent the latter is possible- whether the institution of architecture can be criticized to the same extent that the institution of art has been in recent years.

LH: We have proposed an agenda for the occupation of two different plots of "vacant" land - one in Raleigh, North Carolina, and one in a suburb of Los Angeles located in a hundred-year floodplain. The contexts and relationships for each of the two sites are very different; however, in both cases we began by questioning the accepted practice of a "master" plan at all.

BC: Nevertheless, some differences between art and architecture have to be observed. The viewing subject within architecture may be different from the viewing subject within art; they are constructed through different mechanisms. For instance, in the program description for "Imperfect Utopia" that you sent us in preparation for this discussion you stated that "there is an insepara- ble link between the site and the viewer. One cannot exist without the other. The viewer, present in time,

brings his or her history together to what is observed. Neither the viewer nor the site is a neutral." I agree, and this is a very important issue in architecture. But the viewer of architecture - if this is how you would identify the subject within architecture, because the relationship with architecture also involves all the non- visual senses - stands in a different relationship to the work than the traditional viewer of art. The viewer in the gallery maintains an intellectual relationship in front of the work, a relationship that presupposes distance and concentration. Architecture, on the other hand, is per- ceived in a state of distraction. Most people are not aware of architecture.

MW: Which raises the question of that viewer of the work known as the author. In what state does the author see the work? Concentration or distraction? Is the author aware of the work? What is it for us to be here talking to you today? What is it to publish what you are saying here alongside what you have drawn, photo- graphed, and written in these projects? To artistically lay out this interview in the pages of a "critical" architec- tural journal, to frame it, to design it, to make the interview somehow part of the project? Perhaps we can begin to answer these questions, which will necessarily multiply, by looking at the nature of the collaboration itself. It seems to me that a collaboration, as such, is a kind of mechanism by which one could start to rethink the institution of architecture, which is in so many ways so formidable.

SA: Yes. And the issue of authorship is important also because architecture maintains itself as a discipline by institutionally recognizing certain people, people who have been trained and conditioned in a certain way - as architects. The institutional structure legitimizes their productions and excludes all others. In fact, within architecture the idea of the omnipresent author is espe- cially strong.

BC: And not just within the discipline of architecture. The same idea can be found in popular culture. I read this week in an editorial in the New York Times that Oliver North was exempted from responsibility because he was not the "architect" of the affair.

SA: Perhaps this is a measure of the authority that architects have to assert in order to get anything accom- plished in what is inevitably a collaborative process. In your collaboration, on the other hand, it appears that there are certain moves that would disrupt this institu- tion, these categories. To begin with, there is the mul- tiple authorship, the multiple voices, some of which belong to architects and some not. And then there is

26

~~:::?i.-ii::-:ii?i:li---i:i:i : ::::::: :: : ,-:_iii::iiii??iilaiiii:i'iiiiriii)iiiii :::::::-:_.:-:_.-?.:iiii.iii:iiiii<i7' 77777777/7

"i:_ : : :_ iri:.:?:'??i::-ii iii-'-i-- ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ / 7

::-::-::~~~::-: ::::: :--::--i:;:-?9i:tllilis ?sli ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 77 ig~i: d?(ix~. .; --::::i:-::::77 4 : __.i-:: -:ii- :i : i:-:-- ::::: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7 7

:-: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7 '7::

:::-: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ / ,'77

7,:-i-i-a:::?;-:: 7 7/ 7,7

b *Ib~~~~~~~~~~~j? i--li:bLljb -: . .?? .-' b- 1??.~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~7, 777777

:":i::?::i: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ '7 ':f:7 "'

:::?i~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7'7 77:::::

~ '7 7' 7 '7"777/

7,7~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~i:: :

77 .,: : , , '77:~ - :: -:: :~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~~~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~77

:-:: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ , ' 7: :::::,:? ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 7/ 77 7/ 77 7

7,77. 777 7, 7777

iiii-_ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~777 ~ 7 7 77,, ,7 , 7 ,7 7

-i--iiaii-iiii ---?:? ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 77

:ii- ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~77 ::::: ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7777''7

: :~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~~~~ ~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~7/ 7777

r ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 7 7

:I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~77

*ii:iiiciii2ii ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 77 " 77 77 7 -i~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~:-_ -i-:~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~~ ~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~77

:::~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ /7 :-:-:::- ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 7 , 77 '

7/7777 7/7~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~_::_

LI~~~~u~

I L v &??; ,Li

"\RowEt/El>< ) ' ^-tl'

o- H -R

:;I

i i .. ,.. -----? \?..L2, ?,?,?:. I:-

:I/ J/

--- ??? ,, -:1-- -r Pi

? :? `

I /

assemblage 10

the project itself, some of which is controlled by the collaborative, some of which is not. The figure of the architect seems to begin to disappear here.

LH: In approaching the two projects, we felt that there were issues beyond making "the big statement" on the site that we all shared. We were working together as a kind of exchange and the process for that exchange was a remaking of the "master" plan and the idea of mas- tery. What does it mean to "master" the site? And isn't it presumptuous to assume that one could master the site? How would one go about controlling it all, and do you want to control it? Architecture with a big A is less important than issues of control and occupation. These are questions that should be asked before you put a foundation down.

SA: Perhaps we can talk about the distinctions you did make. In your response to the competition brief for the L.A. arts park, which asked you to work within the plan devised earlier by SOM, and which sounds to me like a typical suburban description of zones and minimal densities, you are reacting to the dispersion of L.A. with a proposal that is in a certain sense more urban, that is to say, it concentrates all the building in one corner and leaves the remaining territory in a kind of artificial "nat- ural" condition. The building marks the corner, which is a typical L.A. strategy. Yet the park does not conform to conventional notions of open space in the city; in fact, it is more rural in character, but "rural" with quo- tation marks. There is a sense that none of this is done straight, that is, a paradoxical sense of pushing these conventional notions of the hundred-year floodplain or the chaparral to a point where their artificiality is exposed. There is a consistent strategy of inversion, which occurs in a formal sense as well.

Zone I Museum

Zone 2 Active Culture

Zone 3 Passive Culture

Zone 3A Passive Culture/ Environmental Conservation

Zone 4 Priority Environmental

Zone 5 Museum Support Service Facility

Zone 5A Museum Support/Service Facility

Zone 6 Environmental Conservation/ Buffer Zone

Zone 6A Environmental Conservation/ Buffer Zone and Artists Residences and Studios

Zone 7 Pinetum

Zone 8 Related Development

NQ: It wasn't simply this particular site we were looking at. It was also a response to the entire flood-control basin, because almost every square inch of the rest of that site has been domesticated; it's golf courses or it's all irrigated. It's very parklike. The Skidmore, Owings & Merrill plan continued that tradition - the sort of quasi-Olmsted, East Coast, green pastoral landscape. We felt there needed to be one place in this whole, huge, thousands of acres where the real indigenous landscape survived.

LH: We had originally thought that we would bring this back to the "natural" landscape, but we questioned what, in fact, was natural or original?

HSM: And we felt that the codification of the California landscape and the clarification of the real conditions should be our primary concerns. Rather than masking the situation by bringing in the Olmstedean reinterpre- tation of the "American" landscape, we should try to develop our own attitude. We feel that in Los Angeles there is a twenty-first-century landscape that hasn't really been defined or understood: a cultivation and development of the land on a very large, regional, intrastate scale. It's a different situation. We took the so- called built cultural product and buried it. We did not "celebrate" the building. By putting the museum under- ground, we could then bring the issue of the ground to the forefront. By compacting the entire park's cultural facilities into one building in the corner, we could then bring the landscape back to a "preexisting" condition that was in itself also artificial - the representation of the idea of what "had been."

BK: Because the site is a floodplain, we thought it would be ecologically sound to condense and limit

I

development to the corner of two strips. By doing so, we hoped we could both maintain an open, functioning space and be conversant with vernacular L.A. strip formation.

LH: The railroad is also very important to the whole scheme because we saw the project as a satellite to the other museums in downtown L.A. We had to question the need for a museum in the first place, the need to replicate what's already in the downtown and on the west side.

BK: We felt we had to rethink the entire master plan "package" that was presented to us. Why put an art space there? Why a Museum of Natural History and what is "natural history" anyway? What did it mean to build a cultural demimegalopolis in the middle of the floodplain in the middle of the valley? The L.A. basin is one of the global capitals of cultural product. Its film and video industries, residential architecture, industrial design, freeway development and soon-to-be-formulated responses to ecological peril work to determine broad systems of representation and control. One of our tactics was to invert the naming of a venerable cultural institu- tion. Our Museum of Un-Natural History would be an expository look at the development and consequences of these enterprises.

BC: The project for a museum of "unnatural history" is a good intersection at which to return to the issue of the institutions of art and architecture, inasmuch as archi- tecture is asked to give form to such a "monumental" institution of art. You seem to be trying here to estab- lish a museum that contains everything. This is, of course, a very Corbusian idea, which your project acknowledges with the spiral - I presume the spiral is a reference to Le Corbusier's project for a Museum of Unlimited Growth.

HSM: It is alright to borrow sometimes.

BC: I'm all for reproductions. I think it is a very appro- priate borrowing. I see the Museum of Un-Natural History as the idea of a cultural record rather than a

collection or a limited selection of auratic objects. In a sense, it is a displacement of the object. It's like a museum of the means of communication.

BK: It could contain buildings, art, movies, TV shows, and goods and merchandise of all sorts.

BC: ... or cars . . .

LH: Cars! Exactly! Cars, products. You could show the latest cereal boxes as easily as paintings. L.A. is about the unnatural; it's all fabrication. All cities are, of course, but in L.A. everything is so new, and its history is very recent.

BK: So much of the art of the last ten years has engaged the vernacular modes of fabrication and communication.

BC: Right. So art, or non-art - because we no longer know much about the difference- in other words, what is contained in the museum, is more about means of communication than about art, both in terms of con- tent (history of cinema, history of freeways, etc.) and in the media used to record and exhibit that content (videotapes of cinema, photographs of the construction of freeways, etc.).

HSM: The minute something is produced it becomes a part of the past in a consumer society. The loss of the idea of permanence suggests a kind of timelessness. In fact, we made the entrance to the Museum of Un- Natural History the projection booth of the drive-in theater.

BC: Yes. Not only are the objects in the museum dis- placed, but the museum itself is displaced. The tradi- tional enclosure is now an open spiral without a facade, or, as Le Corbursier would say of his endless museum, a "frontless museum." And the museum here is under- ground, under a parking lot and a movie screen. Again, the architecture is displaced by other means of communication.

30

0

assemblage 10

HSM: Time, too, is displaced. The spiral has to do with time. We wanted to bring in issues of time, the idea of the temporary and the possibility that architecture can anticipate change and invite alteration.

BC: This displacement of the object and of space as a bounded entity into time is the idea of cinema, an idea that is at home in Los Angeles and that, as you have noted, is clearly translated everywhere in the spectacle of that city. But less clearly, the question of gender is also written into the displacement of the object by the media. I'm thinking here of Barbara's work, whose con- cern for communication and mass culture is also a concern with gender. The "viewer" in your own work is understood to be a gendered subject. How is the "viewer" here in this project, the viewer whom you say cannot be separated from the project, a gendered sub- ject? That is to say, how is your project gendered?

BK: I'd prefer not to gender the project in one way or another. I tend to think about how spaces either accom- modate or resist the breakdown of binary concerns into the incremental moments of differences. This reluct- ance to label or categorize can be seen as a tactic of various feminisms.

BC: Perhaps we could approach this issue indirectly. The idea of a shopping mall, for example. How did you come to the idea of a mall for art in Los Angeles?

LH: As we have said, we were opposed to the idea of the museum as a shrine - isolating art from popular culture. We did not want the interface between the "inside" and the "outside" of the park to be defined by a sharp line. We were interested in unravelling the edges.

HSM: We took two architectural typologies from the region, the covered area, or mall, and the big clearing, or parking lot: the mercado, two very different kinds of space, both dedicated to commerce, both types indige- nous to the regional commercial economies. For us, they were givens, readymades.

LH: In the valley the mall is a very important cultural event.

BK: This is obviously the case across the country. The mall clearly functions as a kind of vertical, climate- controlled Main Street.

BC: I think that to appropriate the shopping mall this generic scene of everyday life - as a readymade is potentially disruptive of the idea of the architectural work as a masterpiece. It seems to me that there is a relation here with Laurie's early work on the domestic interior, where readymades such as found objects from

Canal Street were used to disrupt assumptions not only about the architect-designed interior, the signature work, space signed by the master, the masterpiece, but also the spatial-political organization of the interior, its distri- bution of public and private realms within the interior, its location of authority.

LH: Yes, it is a question of rewriting the program; authority is first located in the voice of the program. The subject of architecture must be revised.

BC: Exactly. The disruption of mastery is first and fore- most a gender issue. What is precisely interesting about shopping malls is that they are used mostly by women, teenagers, the unemployed, and other marginalized groups. I heard on morning television a man who said that when he was feeling depressed he would go for a long walk in the malls. He had cancer. Well, I think there is an issue of accessibility here. Class difference, sexual difference, the difference of various stigmas, all are translated spatially in terms of inside and outside, included and excluded. A woman with a small child may, at a certain moment, prefer to see an exhibition rather than to go shopping, but a traditional museum discourages that. I am not talking only about physical obstacles within the building, but, before all that, about the way in which the building sets itself in relation to its exterior. The mall, as a spatial type, offers an exchange between art and everyday life that the museum as "shrine" is designed to exclude.

BK: The cruising and ambling of the shopping sub- jects plays havoc with the social relation. The relation becomes one of subject to commodity, and this dis- tracted, roaming connection can appear emancipatory because it seems to suggest an escape from both the difficulties and the rigorous pleasures of the social.

MW: It seems to me that the shopping mall idea, which so directly addresses the commodity status of art, might also begin to address the commodity status of architecture. The basic architecture of the shopping mall - but the word architecture is surely inappropriate here - is that of a line, a passage, that is open to the sky and whose sides are defined not by walls but by arrays of consumables receding into the distance. Fixed physical limits are replaced by a depth of commodity. The subject is not contained but suspended, highly mobile, within the array. The traditional movement from the outside to the inside is replaced by a surreal movement from the atopia of the car to the atopia of the mall - if reality is thought of in terms of social relationships and the articulation of the physical world. The status of architecture is displaced. The mall is not

32

assemblage 10

an object. What marks out a shopping mall is that everything is "in" there. And yet this "in" is no longer the simple "in" of enclosure isolated from the world, it is no longer simply an inside. The world is recon- structed within what can no longer simply be called walls. This undermines the fantasy in which the interior is associated with the woman, the domesticated animal who is not in the world, but is tamed within walls by the male who patrols outside in the public domain. The shopping mall operates in the same terms of displace- ment as the Museum of Un-Natural History. It seems to me that this difficulty of establishing a boundary today between the commodity culture and art production is not inscribed in this museum alone.

BK: All boundaries today seem increasingly difficult to defend, although the status of a property line still feels mighty hefty. We are trying to displace categories and collapse divisions, opting, instead, for a series of blurred hybrids.

MW: In this way, you threaten the privileged status of the formal configurations of the individual buildings, thereby disengaging form, depowering it. But more than that, I think the idea of the shopping mall organizes the strategies of the whole project, of which the buildings are but a small part. For instance, if we look at the rhetoric of the project, there is this obsession with including things; you use words like "inclusive," "intact," "reinforce," "brings in rather than leaves out," "inherent," "drive-in," and so on. This inclusivity is the thought of the shopping mall precisely. Your project, by which I mean both your fantasy of action on the site and the multiplicity of documents and events that advertise that fantasy, is a shopping mall. Consequently, the experience of your project would not be that of objects, but the dissemination of objects into commod- ity relations, the rhythm and pulse of desire, the com- pulsion of the fetish. And yet there is a tendency for the project to define itself, at key moments, as object, to raise itself from the banality of the readymade, physical, and cultural landscape to make itself visible. Even in the moment of going underground it stands up. It defines itself as architecture with a capital A.

NQ: But you know how it is with architects, they have to have an object!

MW: Yes, the question is how does one go about depowering that object without inadvertently reconstitut- ing it. Your work goes so far in pursuing strategies for the displacement of objects. Everything is taken to the point of invisibility. But there is this moment of hesita- tion, of reframing, which acts as a decisive limit to the

work. For instance, when arriving from the city, one can perceive certain elements within the landscape that, within the traditional codes, would be understood some- where between architecture and sculpture. For instance, the structure holding up the movie screen will be understood as a kind of artistic reinterpretation of the popular vernacular. And the parking lot formally dis- tances itself from the vernacular world from which it is programmatically drawn. It starts to assume a more strictly architectural condition, it starts to seem to have an outside and an inside. It becomes an object on the landscape, despite the fact that, within it, the Museum of Un-Natural History radically dismantles the divisions between inside and outside. Within each element of the project, a rigorous critique of conventional assumptions is pursued, but the disruptive strategies are themselves somehow framed, contained. The buildings become artistic, architectural, and then they are artistically grouped together in one corner in an ensemble, a figu- rative object set against a ground of landscape strategies. LH: . . . which we call the occupied and the unoccupied. MW: But inasmuch as the division between occupied and unoccupied coincides with the limit of the build- ings, then architecture becomes traditional enclosure again.

SA: I think it's interesting that so much of our discus- sion has centered around the Los Angeles project "Un- Occupied Territory." The "imperfect utopia" of the North Carolina project is difficult to explain, difficult to document, and difficult to talk about. But it is precisely that difficulty that is interesting about it. As Mark says, the Los Angeles project can be recognized as architec- ture inasmuch as we can see it and understand it directly, look at the shape of the buildings, talk about boundaries, talk about how we would perceive it in the landscape. The precise difficulty in talking about the North Carolina project is that it deflects all these ques- tions. Architecture has been dispersed all over the land- scape - I think you used the word "aerosol." It moves away from objects and architectonic resolution. I'm curious, however, to know how much of that is circum- stantial: Are we to see the Los Angeles project as the fulfilled desire of the North Carolina project? Or do the issues of landscape, dispersion, and collaboration tie the two together?

HSM: In the North Carolina project there was a kind of working pragmatism because there was a certain given. The museum itself, the building by Edward Durrell Stone, was involate; it was a built thing there, a cultural object.

33

U

Project Credits Smith-Miller & Hawkinson Archi- tects: Annette Fierro, associate in charge, with Ruri Yampolsky, Peter Morgan, Knut Hansen, John Conaty, Kit Yan, and Jennifer Stearns.

Quennell Rothschild Associates, Landscape Architects: Andrew Moore, Mauricio Villarreal, and Kate Cleary.

Guy Nordenson, Ove Arup & Part- ners, engineering consultant; Pat De Bellis, consulting landscape architect; and Buff Kavelman, art consultant.

North Carolina Museum of Art: Richard Schneiderman, director, and Patricia Fuller, project consul- tant and coordinator.

::w a 0 I a Cuw ssu E.% UUU Mr o r.-

I''''.-'-'-'-.'-.'.' . U -'-'-'..NU

.399 UEUUuU.uuu????.??? MU..??????????????

*.U.UUU..U U U S U?? ????

.U.??????????????

PFTryv I

\'-

^4

hS 7 W

T r 'lb-g

0A - . .-0

v -) I~~~~~~~

k4, E

p

BE

ue

UN- OCCUPIED

If a city can be seen as a dense cluster of civilization, then Los Angeles is a dispersal of these symptoms into a spectacle of affects, a baroque conflation of special effects, a resonant mix of American cultures. In both fact and fiction, LA County has become a laboratory which has extended the notion of what can be called a city. It has shattered the exalted and empowered language of "The Master Plan" into an aerosol of places and non-places, into a rangy gathering of nature and culture, into a random terrain of land, water, dwellings and commerce. Existing as a kind of apex of the inclusive site, LA brings in rather than leaves out, it questions the priorities of style and taste, it makes signs, it makes the permanent temporary and it has no end in sight.

These things that make Los Angeles so compelling are not merely "interesting" eccentricities, but the conditions which define a notion of the 21st century American city. These conditions do not promise an unfettered Utopia, but rather, a combo of rigorous problem solving, seriously witty relthiningres and socially productive balancing acts. But through it all, hopefully, LA will retain its insistent affection for both terrain and contrivance, for both movement and rest. We are talking about an expository city, intent on laying things out, on making itself perfectly clear in a million voices at once, in changing outfits compulsively, in being a bundle of scripts. But it is also an exhibitionist, acting out like crazy and loving being looked at.

We call The Arts Park Center an "Un-Occupied Territory: An Economy of Ecology". But what does this mean and how will it look and feel? What we mean is a way of appropriating the site for a melange of mixed cultural usage while maintaining the pleasures and purposes of an open terrain: a way of mixing natures and cultures, of escaping the conventions of urban occupation which all to often trades the benevolences of an efficient ecology for a kind of force-fed attack of building-itis. Our Arts Park Center will be user- friendly in a real sense: not a ghost town of un-used buildings, not a militantly occupied territory, but a relaxed and sensibly occupied terrain of well-thought structures and spaces which combine the high IQ of culture with the great body of nature.

AN ECONOMIC

*~ERRITORY ^ECOLOGY

Our Arts Park Center will be a site of multiple uses which piles scads of activities under one roof to create a community of interests. The Drive-in combines two of the regions vernacular landmarks, the outdoor movie and the parking lot, both of which serve as the roof of our Museum of Un-Natural History and offer a place for community events. This underground complex will be a grandly riveting exposition of the un-natural or, in other words, the cultural. It will be a literal excavation of cultural development from film technology to automobile design, from dream houses to freeways from supermarket structures to TV sitcoms which all attest to the productive powers of So-Cal inflected American popular culture. It will be a precedent setting exposition of the objects, sound and representations which construct and determine the look and feel of our lives. It will couple a kind of wildly didactic clarity with the fun-loving promises of the spectacle.

The Mall will be an open and expansive structure containing The Showroom, The Supermarket, The Children's Center, the Performing Arts Pavilion, and restaurants. It will be open-ended and flexible, able to accommodate growth and density. Like its vernacular cousins, our Mall will be a seductively inclusive place, beckoning the stroller, the viewer, the snacker, the student and the shopper. The Showroom will be a generously extensive space for looking at and thinking about art and its representations. Its flexibility will allow for a bevy of viewings, from the close-up to the long shot and it will acknowledge contemporary art's ability to understand and represent the power of The Big Picture. When art is shown, its power accumulates and resonates. Our Showroom will foreground this power of showing and work to promote both visual pleasure and critical analysis. The Supermarket will be just that, a marketplace which stresses the superlative and will offer books, posters, maps, videos and an array of objects which relate to the Arts Park's venues and activities.

Surrounding and encompassing these facilities is the park itself, an impressive expanse of land which will be restructured into two distinct areas. The 100 year flood plain will divide the cultivated area and the chaparral and will delineate the difference between

I _ --

the sector of human change and the area of natural alteration. The cultivated area above the flood plain will be a landscape of rotating crops, a garden center, a tree farm and hydroponic gardens. The flood plain, the chaparral, is seen as a terrain where the natural order can begin to be restored where a verticl landscape can beeeeeeeee formed, having its foundations in the damp bottom of the still remarkably unchanneled creek, its midstory in the moist side slopes and its roof in the dry soil of what we assume was once the alluvial plane. The result will be a landscape which follows indigenous rules and provides a microcosm of what the Southern California landscape might be. Irrigation will be held to a minimum, plants will be chosen to adapt to the level in which they are placed and water courses will be modestly altered.

In a considered show of reciprocity, a handshake between nature and culture, it becomes clear that the LA Art Park's open spaces and natural sprawl could not exist without the multiple usage aspect of our Landmark complexes: the folding together of the Drive-ln, Parking Lot and Museum of Un-Natural History and The Mall's sheltering of the Showroom, Supermarket, Children's Museum and Restaurant. This consolidation allows for the Park's vital yet relaxed presence which escapes the militancy of occupation and offers, instead, a kind of emancipatory vista. Traversing the park and running parallel to the highway system will be a network of Skywalks and MetroRails which will function both as enjoyably effective transport and great rooms with a view. We see the entire park as a model of the ecology of the Valley itself: as a reflection of the past and a consideration of the future. "Un- Occupied Territory: An Economy of Ecology" partakes of an adaptive strategy which is sensitive to the vulnerabilities of the environment. It works to preserve open spaces. It works to encourage a kind of critical spectatorship It works to understand the archaeology of cultural histories. It takes pleasure in the secure familiarities of popular landmarks and proposes a heady mix of enlightened leisure and inclusive social responsibility.

O- I O *

a?

O a 0? a O .

~... ... 'a . .: ~.v. ,.. _ ..... a~..~... ...

? ? ? ? . ?ii?IlI ??i??'????

? ? I?

rve~. %.' '.. ?

'-?,Jd~ -mq/"~." - ~ , .'' ?. ? ? (?:l;?.% . ? . .--'m~ _a...'.

? . I?J?i ??? ? ? I?? ? ??' '? ? ? I I? ? '

~.' .Ov~

' . ' . a OAn ? ' a."v / r.? ~?. ~ ~'''---. ~ ? ' '''Y . d l?-

? ?? ?. . . ?? ? I

? ? ' ? ? I'? ?

'i i~C .

i.' ? .

.'m'''

''

II

Oe

.- ? :'*df bg.~,._.- .A' ..V~ ; ;;, :? ?.."

'fl~I; ? ?

? ?m? I

Oil~~~?~ ? 'dl~ ?

.? ~. . ~1? .

... .?..

? ?? ?? ? ? . .? ? ???Ie ~ ?? ??~1 ? ??? ? ? ? ? ?' ?

C~C;. ? ?

?

~ ' .

? ??

I IN ?

?r~m - ? ? ..~~~ - ~ o?I'w d~ ~ ~ e e --' ' ~ ? ? ?? ? ? ? ' ? ? ?*?'''

-'-' ? . . e?I ? ? U b.dl.P-e e-? . .?? .=e . .?.?? ? ? ?em ? ? ? ??? ? ? I ? ?? ? ?

d

h

5?

? ' '

V w,

? ?

????'?I??''"? ???..

W~ .0 O~ ..... . '' ? .' . .'~ '-~-L. O.....?.. _. ~ ~ ''Y

- -,--.... .,,~'',a'.. O . . . . '._._ O"_.&T ~.%'''''''' _-.-.'' O ~O ~L ~.., , O

.

O1 ~....

i %,l..e..llIq?4ee"..---?'-l'''e

' ' - ?

? ]. .m./mee-"m

? ?~~~~~~

p~.~ ~~ e? ? ? ' '. . ? I -j~~???.... Ii mlv ? ?

? tI

??

ttt

0; .:'.

.

.

.O e.'

??? ?e* .?~ ~~~~~~~~~~ o?l~??e

cr ~ ~~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ eelsleo;i ?. 'L " " ?

?~~~~~~? . t .t.i?--mma:;jwo.? ? ?? ?~

, l ? ? .? ~% ~ ? ? ? e ~ d L ~ ? I ]

..~~~.. ?? ?u? ,~ ~ em'? e~m ? ? v im I

? J ?

O

/I ~ ~ ?? I I' I ???? .V ?~? ? ?~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~?? ?? ?

~%.~,___. ? .. L.%)~, ?? '.'" ,. %..

? ~~?? ?

? , ?? ?,??

? . O ,,,..,;-.-.-.-~ It..' >:. -'w O''- ? ?~~~?????~~~

* J~ - .-? .

0%~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.* O.* O * 4III

._,~~ -;c: ..5: ??? ~ ?? ?. '.:, .'.? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~? . ? ? ?.? ? ?

O O

O 40

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ~? ????????l

?? ,

0 f ? ll e4'? e?e .. ....- ..,... .....:.. ..... ....... ? .... ..'-'-' ? '.. ? - .

????? ??? ????? ? r ??? ? ? .??? .??? ? ?a

:;~, . .... ..??? ....??? ?? ?

?~~? ?? i? ? I ????? O_ .? ? ?d"%..

??I?

? t

1 ?? ?O O? 0?

0

I

a 0 0 0 a , O$':.

'-'

O. ,.,. VA a

?

O X 0~?? . ? r??

IN O

? I r %? O a O O O O4b ?

~~~~~hhhhl~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ O ? ???? ??? ~~~~~~? ? ?? ?? ?~~~~No 0 ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~6 0 6oO ooO

?~~? ?i:O

. . .. .. . .

? ??? ???? ?~~~~~~~~~ Oa

.. '?~~~~~~~~ O

OO OO

? ~~~~~~~~??~~~0 ? ii ~~~~~~~ ~~~ ?%x

? ??r i:~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~a d

UnO.Oapd

OCCUPIED/UN-OCCUPIED TERRITORY

LANDSCAPE

LH: But we were not given a program; we produced our own.

HSM: In the Los Angeles project, the culture was sug- gested by the nature of the competition. There we aban- doned the written agenda of the competition, which called for actual buildings almost completely. So while the situation in the North Carolina project seems more ephemeral and nonidentifiable, it actually is operating in a much more restrained and defined context. Whereas the Los Angeles project, which seems more tangible, really has less of a physical context.

SA: It seems to me that the strength of the North Caro- lina project is that it, in fact, isn't an object or a series of objects but rather a series of strategies and scenarios and plans. I'm wondering how true that is of the Los Angeles project, or rather, to what extent it is really an unfinished structure that can be added to and changed over time, to what extent it enters into an aesthetic of the unfinished, making use of the image of the un- finished or the incomplete as an architectural device to encode mutability.

MW: And you don't necessarily specify what happens inside that shed.

BK: The drive-in, the parking lot, the museum, and the shedlike structure should replicate the popular vernacu- lar design of the region, be as generic as possible, and insure that the floodplain not be transgressed.

LH: We were constantly insisting that we didn't have to finish the design of the shed. Having undermined the master plan, having displaced the elements and the pro- gram, whether we made it look one way or another was not important.

MV: Yes, but while the figure of the architect is ques- tioned, and while you intend your buildings to change their form over time, their status as architecture doesn't seem to change. I think it is significant that your docu- ments describe both projects in the same terms, and certainly much of the ideological work is the same. It's a kind of research program in which, presumably, there

MOVEMENTAND CONNECTIONS

could be more projects, more readings. What concerns me is the status of architecture within that program. In the first project you couldn't do anything about the building, it was already there; but in the second, appar- ently free of this constraint, you surprisingly start to reproduce some of the qualities of the first. The institu- tional transition from the bankvault for art to the super- market for art doesn't seem to have disrupted the definition of architecture radically.

LH: You're making an equation between the North Carolina Museum of Art and our mall structure in Los Angeles?

MW: Yes. I understand that the tradition and conven- tions of the discipline cannot simply be abandoned. One can think analogously here of Barbara's own prac- tice, in which the work is placed on the gallery wall in a conventional relationship with its surroundings. It depends upon the very culturally defined gaze of the spectator that it subverts. Likewise, in architecture a critical practice is bound to reassert the very oppositions it wishes to subvert - building/landscape, active/ passive, architecture/art, architecture/building, nature/ culture, site/viewer. But in these projects, the disman- tling of oppositions that goes on within and without the building is not folded back onto the building itself. The limits of the readymade are carefully modulated aesthet- ically to make them visible, the readymade becomes visible as "readymade" - an object that has been appro- priated by an artist-architect, an object that has been signed. One could imagine a nonproject that is just a generic shopping mall with a parking lot punctured by a museum - an invisible project.

HSM: You got it, that's it!

SA: It's outstanding for its banality. It would disappear by virtue of its banality, its ordinariness.

HSM: The most ideal project would be a totally in- visible one in the sense that it would be completely generic. There are adjustments here that you call artis- tic. We call them economic or programmatic. You say it's very artfully done, and, yes, it is. But, on the other

40

The Mall Showroonm Drive-in Museum of Un-Natural History The Travelator The Metro Cultivated Landscape Chaparral Hydroponic Garden

hand, the precepts and the generative strategies did not come from the idea of making something "artistic," but from a very close examination of the kind of economic determinants out of which had developed those kind of forms and situations in Los Angeles. Then we took the actual buildings and examined them again and applied this kind of critical program of art, culture, and com- modity in order to get some kind of typology that could bridge the banal and the special. I'm sure that some- where out there in Los Angeles is a really beautiful mall that was made without an architect. It is a conceit in itself that we would try to do something like that. The real goal here was simply to bring up these issues.

BK: One is always negotiating the vaporous field between presence and absence. But wherever, we always seem positioned in relation to one convention or another. We are brought together today by that relation. Obviously, this exchange itself is motored, in part, by the formalities and conventions of conversations, tran- scriptions, alterations, and the possible posterities prom- ised by publication.

MW: What is extremely important here is to determine the nature of these conventions: what it means to be present, to be political.

BK: I think it's necessary to note the methodological differences between much architectural production and that of the so-called art world. In architecture there seems to be a relatively direct and constant client relationship that must be motored by infusions of capital in order to proceed. Art production can be a more com- pact, hands-on, cottage-industry activity with a more amorphous and mediated client relation. And although the art subculture, like any other "professional" group- ing, is relentlessly hierarchical, it's competitions seem more veiled or are simply called by other names. Archi- tecture tends to use the "competition" as the organizing convention of much of its production.

NQ: There is a seductive nature to the competition, which is that, in a way, you're producing an art com- modity that has to be read strictly on its own terms. Not

like the building that it actually might be, but the sign of a building that it is on the model.

BC: The conventions of a competition are clearly differ- ent from those of the built world. In fact, an architec- tural competition is one of the moments in which architecture gets close to a gallery situation. The other moments are the immediately related ones of publica- tion and exhibition, both of which are represented here. The relation of the competition jury to the work is an attentive, intellectual one - the work is literally hung on the wall. This differs from the distracted mode of the user of a building, a mode closer to that of the viewer of an advertisement.

MW: Clearly, competitions are beauty competitions and the generic shopping mall is precisely not beautiful. The idea of beauty necessarily involves the concen- trated, appropriating gaze, specifically, the eye of the male subject detached from an object, but controlling that object. And, in that sense, it seems to me that what a more complex, collaborative subject - a multiple subjectivity - would construct, or should we say deconstruct, would not be beautiful. It would not sim- ply be visible, available. It would not simply be there. It would be hidden without being underground, but would be somehow, at the same time, so familiar.

BK: "Hidden without being underground," but "at the same timer, so familiar." A "complex, collaborative sub- ject" made right or wrong by its nonbeauty. Sounds like a conventional job description for a wife. (Just kidding.)

MW: I'm speaking of pleasure without an object - an object in the sense that a commodity is an object, understood in terms other than its objecthood: the terms of its exchange, its capacity to act as a substitute. To think of a building as an object, and, more than that, as beautiful or not, is to efface its ongoing status in mass culture in order to appropriate it as a different kind of commodity in the elite discourse of architecture.

BC: This leaves the question of the extent to which the fact that this was a competition affected the way you operated.

41

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9.

THE PLAN

U

NQ: If you judge either of these projects in terms of what the end result would be, you're bound to allow a tremendous difference from what the competition object or the published object is. Both of these projects are not just about formal structures, but about the underlying statements and specifications of how the site is used. And that is really the essence of the message we are getting across. Some of this other stuff was fun, but it was really to accommodate the terms of the competi- tion, in which we were actually being asked to design a building for a site.

BK: We knew that we weren't going to win the compe- tition for the arts park center; but then we really didn't know that.

MW: So, the most important thing to understand is that what counts here is the multiplicity of documents, the collage of different kinds of representation located within the political, rather than a particular fantasy about the end result?

BK: This is a basically discursive practice, which works to undermine the "master plan." We see ours as a dis- cursive and representational activity that thrives on doubt and gets mileage around its ideological displace- ments through representation and through discourse.

Much work seems to depend on critics to provide it with its discourse. We've tried to absorb that critical function and to allow language and process to emerge through a blatantly discursive project.

MW: This seems to place you in a double bind. Archi- tecture is obviously an ideological regime, an institu- tional economy that maintains a certain fantasy about the status of the object that has a very specific political role in our culture. You want to question that fantasy, but to give that questioning political force you have to locate yourself within the very economy you are criticiz- ing: the competition, one object competing against another, the beauty competition. You have to represent an object that you would not want to construct as such. And this interview is, no doubt, part of that representation.

SA: In the art world it seems pretty well accepted that a work of art as such, a finished, coherent object hanging on the wall of the museum or standing in a gallery can enter into the economy of the gallery system, becoming, in effect, a commodity, while at the same time calling into question its status as an object and criticizing the very commodity culture that it participates in. This is all terribly well rehearsed in the critical literature of the

42

art world. And certainly in recent work this is not the result of naYvete or the inability to see the situation. It seems to be supported, on the one hand, by the notion that the gallery can be, in spite of all of its other associ- ations, a free discursive arena, where ideas have some currency - I'm thinking of someone such as Peter Hal- ley, or any of a number of conceptual or postconceptual artists. On the other hand, there is the notion that the artist can subvert and undermine commodity culture by buying into it in an absurd and excessive way - I'm thinking here of artists such as Haim Steinbach or Jeff Koons. So the question seems to have been thoroughly discussed in the context of art production. Yet you said before that to simply translate those ideas into a criti- cism of architectural practice would seem a conservative position to you.

BK: I think our projects have worked to resist stereo- typical limitations. I think there are moments when that resistance falters, and the conventions reassert them- selves. Since we see our work as a series of attempts, since doubt seems to be a generative motor of our pro- duction, we accept these fits and starts as inevitable. I would hope that we are incapable of conducting an "exemplary" practice and that we will never appear "crit- ically correct."

SA: What I am suggesting is that, in architecture, many disruptive strategies appropriated from other discourses can be understood not as strategies of critique but as strategies of legitimation. As architects, we tend to believe that other disciplines are more advanced, more sophisticated in the development of a critical discourse. But when the context is changed, often what looks sub- versive may simply serve to prop up institutions and re- state limits by distracting attention from a rethinking of our own disciplinary practices. This project is perceived as having a certain value inasmuch as it is published in a respected architectural journal, exhibited in galleries, etc. Yet it slips smoothly into the critical apparatus that would legitimize a certain kind of architectural produc- tion without rethinking the process and the conceptual framework that relates criticism to design.

BK: Examinations of "legitimation" are necessary in trying to rethink the circuitries of resistance and control. However, it would be shortsighted, if not disingenuous, to think that the procedures and allowances of legitima- tion are any less pervasive than those of a market econ- omy. We are contained and constructed by these orderings and must work to displace them while existing under their sway. Since some practices are more resis- tant than others, it seems a question of varying incre-

43

assemblage 10

ments of criticality, rather than a naive notion that certain "purer" strategies of critique escape the "impure ambitions" of conventional legitimation tactics.

SA: Well, the notion of critique has been institutional- ized in architecture, too. As in the art world, critical content is very quickly and very smoothly converted into commodity value. There has been an inversion, the institution art has reasserted itself with a particular vehemence here. Now it is precisely in the context we are speaking of - the competition, the gallery, the journal - that this occurs in architecture. That is to say, the critique of architecture as an institution is understood to have a particular value, a value that it does not have in the built world in which perception exists outside the author's control, in which it is "con- summated" (this is the word Walter Benjamin uses) in a state of distraction. It doesn't intrude directly on our consciousness with the intent of calling itself into ques- tion. So how can we read the critique when it doesn't intrude on our conscious perception?

BK: Our projects are not silent. We are trying to nudge the conventions of architecture and the bureaucracies of so-called public art. We hope that our projects and renditions have allowed for a kind of fast and loose exchange, tempered by a reading of how we can "put out" the least to gain the most.

MW: The Los Angeles project has more presence in the media, in this interview in this journal, for example, than it would ever have had it been built.

BK: Of course, we're very aware of this and we hoped it would be the case. As far as the L.A. project was con- cerned, we wanted as little presence as possible. We felt that that site should resist the incursions of a kind of uncritical culture-vulturism. Since our work tries to be conscious of the social relation, we generally feel that the urge to build can, at times, be redirected toward

more compelling demands. Like the reaffirmation of critical sheltering. Like spaces and surroundings that are resistant, yet user-friendly. Like the sheltering of bodies as well as that of art and artifacts. Of course, we can be concerned with both these and other issues. But I'm a failure as a utopian.

SA: The stakes are different in architecture and in art. You seem to be saying that it is part of the agenda of art to somehow mirror or encode the present-day condition - our changed relation to objects, our shelterlessness, our placelessness - to unpack some of the mechanisms that drive our desires, to call these things into question, and perhaps to restructure our thinking about certain institutions both inside and outside of art. Now, archi- tecture is, of course, more intimately of the world than art is; it participates much more directly in the market economy, in relations of production; it by necessity deals with commodification, simply by its positioning. Yet in spite of this, or perhaps because of this, its con- ventions are all that more solidified and resistant to change. Would you say that, unlike art, it is not part of architecture's agenda, not the job of architecture, to describe this contemporary condition? It interests me that you talk about the need for shelter. Is it possible to make a place that at the same time speaks to us about being displaced? Or further, that does so in an interest- ing way? Because these sorts of places exist already, and we don't want to simply mirror existing reality in an uncritical way.

BK: Obviously, one hopes for lots of different kinds of practices that can join the pleasures and allowances of theory with an awareness of social conditions and that subsequently become material through construction. We are not enchanted by the formalities, beauties, and fantasies of a utopian project that works to efface the body. We are more concerned with the vulnerabilities of bodies, the recognition of their differences, and the amplification of their voices.

Project Credits Smith-Miller & Hawkinson Archi- tects: Knut Hansen, associate in charge, with Annette Fierro, Kit Yan, Peter Morgan, Ruri Yampolsky, Jennifer Stearns, John Conaty, Alexis Kraft, and Jorge Aizenman.

Quennell Rothschild Associates, Landscape Architects: Mauricio Villarreal.

Guy Nordenson, Ove Arup & Partners, engineering consultant.

Special thanks to the New York State Council on the Arts, Archi- tecture, Planning and Design Program, for their support.

xi,~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

..... .....~~~~~,&