Ascomycetes associated with ectomycorrhizas: …...Ascomycetes associated with ectomycorrhizas:...

Transcript of Ascomycetes associated with ectomycorrhizas: …...Ascomycetes associated with ectomycorrhizas:...

Ascomycetes associated with ectomycorrhizas:molecular diversity and ecology with particularreference to the Helotialesemi_2020 3166..3178

Leho Tedersoo,1,2* Kadri Pärtel,1 Teele Jairus,1,2

Genevieve Gates,3 Kadri Põldmaa1,2 andHeidi Tamm1

1Department of Botany, Institute of Ecology and EarthSciences, University of Tartu, 40 Lai Street, 51005Tartu, Estonia.2Natural History Museum of Tartu University, 46Vanemuise Street, 51005 Tartu, Estonia.3Schools of Agricultural Science and Plant Science,University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania 7001,Australia.

Summary

Mycorrhizosphere microbes enhance functioning ofthe plant–soil interface, but little is known of theirecology. This study aims to characterize the asco-mycete communities associated with ectomycorrhi-zas in two Tasmanian wet sclerophyll forests. Wehypothesize that both the phyto- and mycobiont,mantle type, soil microbiotope and geographical dis-tance affect the diversity and occurrence of the asso-ciated ascomycetes. Using the culture-independentrDNA sequence analysis, we demonstrate a highdiversity of these fungi on different hosts andhabitats. Plant host has the strongest effect on theoccurrence of the dominant species and communitycomposition of ectomycorrhiza-associated fungi.Root endophytes, soil saprobes, myco-, phyto- andentomopathogens contribute to the ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycete community. Taxonomicallythese Ascomycota mostly belong to the orders Helo-tiales, Hypocreales, Chaetothyriales and Sordariales.Members of Helotiales from both Tasmania and theNorthern Hemisphere are phylogenetically closelyrelated to root endophytes and ericoid mycorrhizalfungi, suggesting their strong ecological and evolu-tionary links. Ectomycorrhizal mycobionts from Aus-tralia and the Northern Hemisphere are taxonomicallyunrelated to each other and phylogenetically distant

to other helotialean root-associated fungi, indicatingindependent evolution. The ubiquity and diversity ofthe secondary root-associated fungi should be con-sidered in studies of mycorrhizal communities toavoid overestimating the richness of true symbionts.

Introduction

Endophytic and mycorrhizosphere microbes, especiallyBacteria, Archaea and microfungi, synthesize plantgrowth regulators and vitamins facilitating the develop-ment and functioning of the mycorrhizal system in soil(Schulz et al., 2006). These root-associated microbessuch as mycorrhiza helper bacteria and the nitrogen-fixing actinobacteria and rhizobia differ substantially intheir function and ecology, including host preference pat-terns (Benson and Clawson, 2000; Sprent and James,2007; Burke et al., 2008). Of microfungi, foliar endo-phytes may considerably vary according to the special-ization to different host species and even organs(Neubert et al., 2006; Arnold, 2007; Higgins et al., 2007).On the contrary, facultative root-associating fungi suchas endophytes (e.g. the Phialocephala–Acephala andMeliniomyces–Rhizoscyphus complexes) form mostlynon-specific associations with many plant hosts (Vrålstadet al., 2002; Chambers et al., 2008), although host pref-erence may occur on the cryptic species level (Grüniget al., 2008).

Despite numerous studies on isolation and morphol-ogical identification of ascomycetous microfungi fromectomycorrhizal (EcM) root tips, their specificity for hostplants, fungi and substrate types remains unknown(Melin, 1923; Fontana and Luppi, 1966; Summerbell,1989; Girlanda and Luppi-Mosca, 1995). Molecular toolshave only recently been used to characterize and distin-guish the secondarily associated microfungi from EcMfungi in situ. These microfungi were identified from EcMroot tips by either cutting additional bands from the gel(Rosling et al., 2003; Tedersoo et al., 2006), using specificprimers (Urban et al., 2008) or cloning (Morris et al.,2008a,b; 2009; Wright et al., 2009). Cloning from DNAextracts comprising pooled individual EcM root tipsreveals many ascomycete taxa of uncertain ecologicalrole (Bergemann and Garbelotto, 2006; Smith et al.,

Received 9 April, 2009; accepted 22 June, 2009. *For correspon-dence. E-mail [email protected]; Tel. (+372) 7376222; Fax(+372) 7376222.

Environmental Microbiology (2009) 11(12), 3166–3178 doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02020.x

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2007). Many of these are endophytic or rhizoplane colo-nists that are accidentally reported as forming mycorrhi-zas both in research publications and InternationalSequence Database (INSD) entries (Grünig et al., 2008).Such uncertain reports are especially common in ericoidmycorrhizas (ErM) and EcM for which universal fungal-specific primers are routinely used for the identification ofmycobionts.

Helotiales (Ascomycota) comprises the largest numberof undescribed root-associated fungi in addition toapproximately 2000 described species with contrastinglifestyles (Wang et al., 2006). Various subgroups ofHelotiales such as the Phialocephala–Acephala andRhizoscyphus–Meliniomyces complexes and Lachnumspp. are identified from EcM and arbutoid mycorrhiza inforest trees and subshrubs of the Northern Hemisphere(Vrålstad et al., 2002; Rosling et al., 2003; Tedersoo et al.,2003; 2007; 2008a; Bergemann and Garbelotto, 2006)and often erroneously reported as truly mycorrhizal.Indeed, the ecologically heterogeneous Rhizoscyphus–Meliniomyces and Phialocephala–Acephala complexesboth include distinct EcM-forming species nested withinnumerous pathogenic, ErM and root endophytic taxa(Vrålstad et al., 2002; Hambleton and Sigler, 2005;Münzenberger et al., 2009).

In previous EcM fungal community studies in Tasmania,we encountered frequent secondary colonization of EcMroot tips by Ascomycota besides the predominatelybasidiomycetous EcM fungi (Tedersoo et al., 2008b;2009). The present study was undertaken to identify anddistinguish these EcM-associated Ascomycota (EAA)from the true EcM-forming mycobionts using a culturing-independent approach. Utilizing the DNA extracts fromsingle EcM root tips with preidentified plant and EcMfungal hosts and developing several ascomycete-specificprimers, we hypothesized that these EAA have prefer-ence for either host tree, host fungus lineage, EcM mantletype, soil microbiotope, plot and site. Because of thedominance of Helotiales in this and previous studiesinvolving root-associated fungi, we addressed the phylo-genetic relations of helotialean EcM, ericoid mycorrhizal,endophytic and EAA isolates using the rDNA 28Ssequence data.

Results

Identification and distribution of EAA

Application of the newly designed taxon-specific primers(Fig. 1; Appendix 1) allowed us to specifically amplifyAscomycota from EcM root tips. Based on the rDNA ITSsequence analysis, 251 individuals of EAA were identifiedfrom 226 out of 675 (33.5%) analysed root tips (148individuals from the Mt. Field site and 103 from the Warrasite). 88.9% of the EcM root tips yielded a single ampliconof EAA. Based on the 99% ITS barcoding threshold, EAAwere assigned to 105 species, including 69 (65.7%)singletons and 15 (14.3%) doubletons (Appendix 2).

At both sites, species of EcM fungi and EAA wereaccumulating at similar rates with increasing samplingeffort (Fig. 2). The species accumulation curves hadstrongly overlapping confidence intervals (not shown)suggesting no substantial difference in EAA diversityamong mantle types, sites, plots, microsites or plant andfungal hosts. Similarly, there were no statistically signifi-cant differences in the relative frequency of colonization ofEAA among these habitats.

Trends in the distribution of eight most frequent EAAspecies were statistically analysed at both two sites(Table 1). Five of these species differed significantlyaccording to the site. Only Lecanicillium flavidum (syn.Verticillium fungicola var. flavidum) displayed a statisti-cally significant preference for EcM fungal lineage (Fish-er’s exact test: d.f. = 4; P = 0.002). This species occurredmore frequently on root tips colonized by members ofthe/cortinarius lineage, compared with the other four mostcommon EcM lineages. Due to elevated abundanceon the/cortinarius EcM, L. flavidum was more commonon plectenchymatous mantles than expected (d.f. = 1;P = 0.004). In contrast, Helotiales sp016 colonized exclu-sively mycorrhizas with pseudoparenchymatous mantles(d.f. = 1; P = 0.001).

Among the seven most common EAA species at Mt.Field, host trees and plots affected the distribution of sixand two species respectively (Table 1). Putative rootendophytes, root parasites and mycoparasites includedspecies with significant host plant preference. Forexample, Helotiales sp008 (putative endophyte, d.f. = 2;

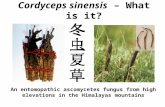

Fig. 1. Map of primers used for amplification of the ITS and 28S rDNA. Newly designed primers are given in bold.

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3167

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

P = 0.001) and L. flavidum (mycoparasite; d.f. = 2;P = 0.043) occurred significantly more frequently on EcMof Eucalyptus regnans, while Hypocreales sp086 (rootparasite Neonectria cf. radicicola; d.f. = 2; P = 0.018)

preferred Pomaderris apetala compared with the othertwo hosts (Nothofagus cunninghamii is the third host). Atthe Warra site, only L. flavidum was significantly morecommon in the forest floor soil compared with decayedwood (d.f. = 1; P = 0.027).

At Mt. Field and Warra, respectively, the multivariatemodel explained 19.3% and 17.6% of the total variation inthe distribution of EAA. At both sites, the fungal lineageand mantle anatomy explained < 2% of the total variationthat remained non-significant. At Mt. Field, host plant andplot contributed 7.2% (SS = 141.2; P = 0.001) and 3.0%(SS = 59.0; P = 0.003) respectively. At Warra, substratetype contributed 3.5% to the total variation (SS = 34.7;P = 0.008).

Phylogenetic affinities of Tasmanian EAA

Based on blastN matches, the Tasmanian EAA belongedto 12 orders of Pezizomycotina. Helotiales, Hypocreales,Chaetothyriales and Sordariales comprised 54, 21, 9 and8 species respectively. Many of the hypocrealean taxawere assigned to parasitic lifestyle, including six putativemycoparasites (L. flavidum, Hypomyces spp.), four rootparasites (e.g. Neonectria radiciicola, Cylindrocarpon sp.)and two insect parasites (Cordyceps spp.). Sordarialesand Chaetothyriales, respectively, comprised mostlysaprotrophic and putatively endophytic members.

Helotiales comprised most of the dominant species thatwere assigned to the endophytic lifestyle based on ITSmatches (Appendix 2) and phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3).The 30 species of Tasmanian EAA with available 28Ssequence formed 10 distinct, more or less supported lin-eages, including both monospecific branches and aggre-gates comprising up to 17 species (the Hyphodiscuscomplex) (Fig. 3). Helotialean EAA and root endophytesfrom Tasmania and the Northern Hemisphere were

00

10

20 40 60 80 100 120 140

20

30

40

50

60

70

80N

umbe

rof

spec

ies

Number of individuals

Fig. 2. Species accumulation curve of ectomycorrhizal (opensymbols) and ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes (closedsymbols) at the Mt. Field (triangles) and Warra (circles) sites. Forclarity, the overlapping confidence intervals are not shown.

Table 1. Statistical significance of host plant, microbiotope, site and mantle type on the occurrence of eight most common species ofectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes. Significant P-values are indicated in bold.

Species Putative ecology

P-values of a Fisher’s exact test

Mt. Field Warra Both sitesa

Host plant(d.f. = 2)

Plot(d.f. = 2)

Micro-biotope(d.f. = 1)

Mantle type(d.f. = 1)

Site(d.f. = 1)

Helotiales sp007 Endophyte 0.018 0.091 na 0.401 < 0.001Helotiales sp008 Endophyte 0.001 0.007 na 0.241 0.342Helotiales sp013 Endophyte 0.554 0.193 na 0.540 0.004Helotiales sp016 Endophyte < 0.001 0.012 na 0.001 < 0.001Helotiales sp029 Endophyte na na 0.059 0.733 < 0.001Helotiales sp038 Endophyte 0.007 0.556 0.077 0.782 0.010Hypocreales sp086 Root parasite 0.018 0.279 na 0.542 0.635Lecanicillium flavidum Mycoparasite 0.043 0.125 0.027 0.003 0.854

a. Based on G-tests.Molecular identification of these species is shown in Appendix 2.na, not applied because of insufficient replication.

3168 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

Fig. 3. Maximum-likelihood phylogram of Tasmanian ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes (in bold) among identified taxa and otherplant-associated fungi within Helotiales. Fast bootstrap values > 70 and Bayesian posterior probabilities >95% are indicated below and abovethe branches respectively. Asterisks denote confirmed and putative EcM isolates, although it is possible that other EcM Helotiales exist.

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3169

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

phylogenetically closely related to ErM and saprobic iso-lates in the Hyphodiscus, Cryptosporiopsis–Neofabraeaand Rhizoscyphus–Meliniomyces complexes (Fig. 3,Appendix 2). Similarly, the majority of EAA sequencesfrom the Pinaceae and Fagaceae hosts in the NorthernHemisphere usually clustered with the well-recognizedendophytic and/or ErM lineages, whereas a few groupsformed monotypic lineages with yet unknown ecology(e.g. isolates AY394891, DQ273463, DQ273467 andEU563495).

The Tasmanian helotialean EcM species that have beenconfirmed by mycorrhiza anatomy and consistent molecu-lar identification (cf. Tedersoo et al., 2008b, 2009; L. Ted-ersoo, unpublished) were clustered in four distinctlineages (Fig. 3). These Tasmanian EcM lineages wereclearly distinguished from EAA, endophytes, ErM isolatesand the two EcM lineages distributed in the NorthernHemisphere (/meliniomyces and an unnamed lineage)based on both ITS (Appendix 2) and 28S (Fig. 3)sequence data.

Discussion

Diversity of EAA

Ascomycota comprises common and taxonomicallydiverse secondary colonists on EcM root tips. Our resultscorroborate previous reports of high local diversity of rootand foliar endophytes in various ecosystems (Vandenk-oornhuyse et al., 2002; Sieber and Grünig, 2006; Arnold,2007; Higgins et al., 2007). We detected no statisticaldifference in the diversity of EAA among the host plantsand fungi, microbiotope, plot and site, indicating thatnone of these substantially affect the naturally high EAAdiversity.

Among the factors investigated, host plant had thestrongest effect on the frequency of individual EAAspecies. This agrees with studies on foliar endophytes(Arnold and Lutzoni, 2007), but contrasts with previousresearch on root endophytes that detected no significantdifferentiation according to the host plant (Narisawa et al.,2002; Sieber and Grünig, 2006; Chambers et al., 2008;but see Grünig et al., 2008). However, methodologicaldifferences such as choice of a barcoding threshold andinclusion of the culturing step may account for the discrep-ancies. We speculate that host generalists, e.g. mostmembers of the Trichoderma, Phialocephala–Acephalaand Rhizoscyphus–Meliniomyces complexes, may befavoured by culturing due to their relatively rapid mycelialgrowth and non-specialized ecology. Similarly, lower DNAbarcoding thresholds may result in lumping of closelyrelated taxa that are often ecologically differentiated(Summerell and Leslie, 2004; Sharon et al., 2006; Grüniget al., 2008). Host preference among EAA (this study),

foliar endophytes (Arnold, 2007), EcM symbionts (Molinaet al., 1992; Tedersoo et al., 2008b) and arbuscularmycorrhizal symbionts (Vandenkoornhuyse et al., 2003)suggest that plant diversity, through the niche comple-mentarity effect, may promote the diversity of both com-mensal and mutualistic fungi above and below ground.The relatively stronger effect of plant host compared withplot, site and microbiotope effects on EAA species andcommunities suggests that interspecific differences inphytochemistry play a more important role in structuringthe distribution of EAA compared with qualitative differ-ences in the soil matrix and geographical distance.

Based on INSD search and phylogenetic analysis, mostof the EAA represented root endophytes, with a minorityhaving strongest affinities to plant parasites, mycopara-sites, insect parasites and soil saprobes. While the lattermay be rhizoplane fungi, root endophytes and plant para-sites are the expected root colonists (Vandenkoornhuyseet al., 2002; Neubert et al., 2006). Their ubiquitous asso-ciation with ectomycorrhizas and the negligible effect offungal host indicates that the fungal mantle is not neces-sarily an effective barrier to the colonization of endophyticand potentially parasitic fungi. Moreover, endophytic fungioften proliferate in the fungal mantle, developing hyphaewith hyaline or melanized cell walls (L. Tedersoo, pers.obs.).

Our results suggest that EcM root tips provide a habitatfor mycoparasitic fungi that normally infect fruit-bodiesabove ground. This study confirms previous reports onidentification of the Lecanicillium fungicola complex fromEcM root tips and associated soil (Summerbell, 1989) andsuggests that some mycoparasites (such as L. flavidum)may be relatively frequent in ectomycorrhizas. Theobserved preference of L. flavidum for cortinarius EcM hasnot been detected in case of the more general fungalfruit-body parasitism by L. flavidum or the closely relatedL. fungicola (Zare and Gams, 2008; K. Põldmaa, pers.obs.). The rarity of other mycoparasites among the EAAmay be ascribed to their host specificity (Põldmaa, 2000) orscarcity of their below ground associations. However,given the strongly seasonal production of suitable fruit-bodies, it is not surprising to find mycoparasites on EcMthat are active throughout the year. The ecology of EAA onEcM root tips, particularly the potential to spread along withthe EcM hyphae and rhizomorphs that give rise to fruit-body primordia, warrants further investigation. Similarly,Arnold (2008) noted the presence of certain entomopatho-gens among foliar endophytes and suggested that their lifecycle may include both insect and plant hosts.

In the perspective of EcM communities, the presence ofEAA hamper molecular identification and interpretation ofresults. Even small supplement of EAA DNA may becoamplified, resulting in double signal in sequence chro-matograms or, worse, the preferential amplification of

3170 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

EAA (Rosling et al., 2003). To be able to separate thetargeted EcM fungi from these ‘contaminant’ secondarycolonizers, both morphological and molecular aspects ofEcM fungal communities need to be addressed. This cau-tions against pooling large amounts of roots prior to DNAextraction that disables post hoc morphological confirma-tion of the molecularly identified fungi (Bergemannand Garbelotto, 2006). We predict that ongoing high-throughput sequencing studies addressing mutualisticEcM fungi and soil eukaryotes will create thousands ofsequences from putative root endophytes, whose identityand actual ecology can easily be misinterpreted (Nilssonet al., 2009).

Phylogenetic affinities of EAA

Most of the EAA in the two Tasmanian sites belong to theHelotiales. This agrees well with previous sporadic reportsof EAA in EcM fungal communities (Bergemann and Gar-belotto, 2006; Smith et al., 2007; Morris et al., 2008a,b;2009; Urban et al., 2008; Wright et al., 2009) as well asthe more focused studies on root endophytes (Vandenk-oornhuyse et al., 2002; Vrålstad et al., 2002) and ErMfungi (Allen et al., 2003; Bergero et al., 2003) in theNorthern Hemisphere. Similarly, the Cladophialophora–Exophiala–Capronia group of Chaetothyriales is acommon facultative root endophytic taxon, althoughmembers of this group have been found from a variety ofsubstrates (Narisawa et al., 2002; 2007). The Hypocre-ales and Sordariales, represented here by parasitic orsaprobic members, are detected as infrequent root colo-nizers in studies on root endophytic fungi. These twoorders, as well as Dothideomycetes, dominate amongfoliar endophytes in angiosperms (Arnold, 2007; Higginset al., 2007).

We paid particular attention to phylotype distributionwithin Helotiales, because this was the most importantorder in terms of EAA frequency and diversity, andalso comprised EcM-forming fungi. The Tasmanian EAAspecies formed several mono- or multispecific lineagesthroughout the Helotiales, particularly clustering withthe Hyphodiscus, Oidiodendron and Cryptosporiopsis–Neofabraea complexes from the Northern Hemisphere.Except for the Cryptosporiopsis–Neofabraea clade, thesetaxa are not included in the 18S + 28S rDNA phylogeniesof Wang and colleagues (2006) and therefore, their phy-logenetic position within the Helotiales remains obscure.

Both the phylogenetic analysis and INSD searchessuggest substantial taxonomic overlap among Tasmanianand boreal EAA, root endophytes and ErM fungi. Previousstudies have suggested that several ErM fungi and rootendophytes may be conspecific based on identical culturemorphology (McNabb, 1961), synthesis trials (Bergeroet al., 2000) and molecular identification (Bergero et al.,

2000; Piercey et al., 2002). Moreover, many of these fungiare common saprobes in soil and peat (Piercey et al.,2002). Enzymatic tests have revealed relatively highlevels of cellulolytic activities in ErM and endophytic fungicompared with EcM symbionts (Mandyam and Jump-ponen, 2005). These elevated enzymatic activities maycontribute to the improved nutrition of ericoid plants inhighly organic, nutrient-poor soils (Read et al., 2004).Among hyperdiverse soil saprobes, members of the Cha-etothyriales and Helotiales in particular display frequentendophytic colonization. We suggest that Ericalesevolved capacities to host these endophytes in individualroot cells and stimulated the formation of coils forimproved nutrient exchange, thus giving rise to the ericoidmycorrhiza. ErM fungi and root endophytes largelyoverlap in many groups within Helotiales (Bergero et al.,2000; Chambers et al., 2008), Chaetothyriales (Usuki andNarisawa, 2005) and Sebacinales (Selosse et al., 2007).

Species of confirmed helotialean EcM fungi from Aus-tralia and Europe formed four and two distinct lineagesrespectively. There were no close relationships betweenEcM Helotiales from Australia and the Northern Hemi-sphere, suggesting that in both regions, EcM lifestylemay have evolved multiple times independently in thistaxon. Except for the /meliniomyces and /acephalamacrosclerotiorum lineages (Hambleton and Sigler, 2005;Münzenberger et al., 2009), EcM fungal taxa have noclear closely related ErM or root endophytic sister groups,suggesting different origin of EcM and other rootbiotrophic lifestyles. Therefore, taxonomic breadth of thepostulated common guild between EcM and ErM myco-bionts (Vrålstad et al., 2002; Bougoure et al., 2007) aswell as their evolutionary and ecological differencesrequire further clarification.

In conclusion, ascomycetes associated with ectomyc-orrhizas are highly diverse and comprise root endophytes,saprotrophs, myco-, phyto- and entomopathogens. Thedistribution of these microfungi is influenced by plant hostrather than EcM fungi, substrate type or geographicalvariables. Within Helotiales, EAA and the putative ecto-mycorrhizal symbionts are distantly related and probablyevolved multiple times independently in the Northernand Southern Hemisphere. In studies of mycorrhizalcommunities, the ubiquity and diversity of secondaryroot-associated fungi should be considered to avoidoverestimating the diversity of the true mycorrhizalsymbionts.

Experimental procedures

Sample preparation

Root sampling was performed in two Tasmanian wet sclero-phyll forest sites, Mt. Field (42°41′-S, 146°42′-E) and Warra(43°04′-S; 146°40′-E) as described in detail in Tedersoo and

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3171

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

colleagues (2008b; 2009). Briefly, EcM root tips of matureN. cunninghamii (Hook.) Oerst., E. regnans F. Muell. andP. apetala Labill. were sampled in forest floor soil from 45 soilcores (15 cm¥ 15 cm to 5 cm depth) in three 1 ha plots at Mt.Field. At Warra, root tips of only N. cunninghamii weresampled from 42 cores in decayed wood and 22 cores inforest floor soil. EcM root tips were sorted into morphotypesand anatomotypes using a stereomicroscope. Particular carewas taken to characterize and record the anatomy of EcMformed by Ascomycota (L. Tedersoo, unpublished). SingleEcM root tips, one to four from each anatomotype per soilcore, were carefully cleaned from the adhering soil and debrisand subjected to DNA extraction, PCR amplification andsequencing as described in Tedersoo and colleagues(2008b). The EcM symbionts were identified based on bar-coding of the rDNA Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region.Roots from different host trees were initially distinguishedbased on morphological characters such as colour, branchingand thickness, and confirmed based on the length polymor-phism of the plastid trnL region (Tedersoo et al., 2008b).

From the DNA extracts of single root tips that were suc-cessfully ascribed to EcM plant and fungal species (Tedersooet al., 2008b; 2009), we targeted the associated Ascomycotausing the combination of a fungal-specific primer ITSO-FT(5′-acttggtcatttagaggaagt-3′) and the Ascomycota-specificLA-W (5′-cttttcatctttcgatcactc-3′) (Fig. 1). The Ascomycotawere specifically addressed, because a vast majority of soilfungi and endophytes belong to this phylum (Vandenkoorn-huyse et al., 2002; O’Brien et al., 2005; Arnold, 2007). We areaware that certain Basidiomycota such as Ceratobasidiumand Cryptococcus, and Zygomycota may also contribute tothe root endophytic fungal community especially in theculture-based studies, but form a minor component(Summerbell, 1989; Hoff et al., 2004; Neubert et al., 2006).Because most EcM root tips were associated with a single orno species of EAA (based on preliminary PCR surveys), onlydirect sequencing of the PCR products was performed,neglecting the cloning step. When several fungi were presenton root tips as revealed from double DNA bands on 1%agarose gels, the DNA fragments were cut from the geland re-amplified using the internal primers ITS5 (5′-ggaagtaaaagtcgtaacaagg-3′) or ITS1 (5′-tccgtaggtgaacctgcgg-3′)and ITS4 (5′-tcctccgcttattgatatgc-3′). Because the resultsrevealed dominance of Helotiales and Sordariomycetes, wefurther designed taxon-specific reverse primers, ITS4-Sord(5′-cccgttccagggaatct-3′), LR6-Sord (5′-gtttgagaatggatgaaggc-3′) and LR6-LS (5′-aaaatggcccactagtgttg-3′) in the 28SrDNA to specifically target these taxa. To address phyloge-netic relationships among the species of Helotiales, weamplified the 28S rDNA using a fungal specific primerLR0R (5′-acccgctgaacttaagc-3′) in combination with eitherof the newly developed Pezizomycotina-specific primerLR3-Asc (5′-cacytactcaaatccwagcg-3′) or Leotio- andSordariomycetes-specific LR6-LS (Fig. 1; Appendix 1). TheITS region of EAA was sequenced using the primers ITS4,ITS1, ITS5 and/or LF340 (5′-tacttgtkcgctatcgg-3′); 28S rDNAwas sequenced using the primers ctb6 (5′-gcatatcaataagcggagg-3′), TW13 (5′-ggtccgtgtttcaagacg-3′) and/or LR5(5′-tcctgagggaaacttcg-3′). Sequences were further trimmed,assembled and edited using Sequencher 4.7 software(Genecodes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Based on the clus-

tering of ITS sequences belonging to the Helotiales in thepresent study and in previous research (Hambleton andSigler, 2005; Grünig et al., 2009), 99.0% was selected as auniversal barcoding threshold to distinguish between putativespecies. All unique ITS and partial 28S rDNA sequences aredeposited both in INSD (Accession Numbers FN298677–FN298803) and UNITE (UDB004100–UDB004230) publicdatabases.

Thirty 28S rDNA sequences (typically 600–900 bp span-ning divergent domains D1–D2 or D1–D3) of helotialean EAAfrom Tasmania were automatically aligned with publishedendophyte, ErM, EcM and preidentified fruit-body sequences(retrieved from INSD and UNITE public databases) usingMAFFT 5.861 (Katoh et al., 2005). Obvious alignment errorswere checked and edited manually. The final data set com-prised 167 taxa and 1335 characters. Using the onlineversion of RAxML 7.0.4 (Stamatakis et al., 2008), a maximumlikelihood phylogram with 100 fast bootstrap replicates wasconstructed following the GTR + G + P base substitutionmodel. Posterior probabilities were estimated with MrBayes3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) using the samemodel (parameters: lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma). Two par-allel MCMC analyses were performed, both initiated withrandom starting trees and run for 10 000 000 generations.Every 100th generation was sampled. The first 10 000 treeswere discarded as burn-in. Posterior probabilities werecalculated from the remaining 90 000 trees sampled from9 000 000 generations.

Statistical analyses

G-tests were applied to detect statistically significant differ-ences in the occurrence of EAA among host fungal lineages,host plant species, mantle types, sites, plots and micro-biotopes. The effects of host fungus, mantle type and site onthe frequency of the eight most common EAA were furtherstudied based on the pooled sites and occurrence of EAAindividuals in each class, using Fisher’s exact tests. Morespecifically, the effects of plant host and plot were addressedat the Mt. Field site and microbiotope at the Warra site,following the same procedure. To study the differences inaccumulating species richness among each of the factors, wecalculated individual-based rarefaction curves with 95% con-fidence intervals using a computer program EstimateS 8.0(Colwell, 2006). Accumulating species richness of EAA wascompared with that of EcM fungal species identified from thesame EcM root tips.

Using a computer program DISTLM forward 1.3 (McArdleand Anderson, 2001), we studied the effect of fungal hostlineage, microsite and mantle anatomy on EAA communitycomposition of N. cunninghamii EcM at the Warra site. Inanother analysis, we addressed the effects of fungal hostlineage, plant host species, plot and mantle anatomy on EAAcommunity structure at the Mt. Field site. In both multivariateanalyses, occurrence of an EAA formed a sampling unit (i.e.individual). Singletons were removed from the analyses.Thus, the Mt. Field and Warra data sets comprised 22 and 17species as well as 112 and 65 individuals respectively. EcMfungal lineages with at least three occurrences were includedas dummy variables. The occurrence of individuals was

3172 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

standardized by sums of variables (EAA species). Chi-squaredistance was used as a distance metric with 999 permuta-tions. Significance level a = 0.05 was used in all statisticalanalyses.

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Kantvilas, D. Ratkowsky, N. Ruut and D.Puskaric for support in Tasmania; H.-O. Baral for voucherspecimens; D. Ratkowsky for helpful suggestions on anearlier draft of the manuscript. This study was funded byEstonian Science Foundation Grants no. 6606, 6939, 7434and JD92, Doctoral School of Environmental Sciences, Krist-jan Jaak scholarship and FIBIR/rloomtipp. G.G. is supportedby Forestry Tasmania, Holsworth Wildlife Research Endow-ment Fund, CRC for Forestry and Bushfire.

References

Allen, T.R., Millar, T., Berch, S.M., and Berbee, M.L. (2003)Culturing and direct DNA extraction find different fungi fromthe same ericoid mycorrhizal roots. New Phytol 160: 255–272.

Arnold, A.E. (2007) Understanding the diversity of foliarendophytic fungi: progress, challenges, and frontiers. FungBiol Rev 21: 51–66.

Arnold, A.E. (2008) Endophytic fungi: hidden components oftropical community ecology. In Tropical Forest CommunityEcology. Carson, W.P., and Schnitzer, S.A (eds). Oxford,UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 254–271.

Arnold, A.E., and Lutzoni, F. (2007) Diversity and host rangeof foliar fungal endophytes: are tropical leaves biodiversityhotspots? Ecology 88: 541–549.

Benson, D.R., and Clawson, M.L. (2000) Evolution of theactinorhizal plant symbioses. In Prokaryotic Nitrogen Fixa-tion: A Model System for Analysis of Biological Process.Triplett, E.W. (ed.). Wymondham, UK: Horizon ScientificPress, pp. 207–224.

Bergemann, S.E., and Garbelotto, M. (2006) High diversity offungi recovered from the roots of mature tanoak (Lithocar-pus densiflorus) in northern California. Can J Bot 84:1380–1394.

Bergero, R., Perotto, S., Girlanda, M., Vidano, G., and Luppi,A.M. (2000) Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are common rootassociates of a Mediterranean ectomycorrhizal plant(Quercus ilex). Mol Ecol 9: 1639–1649.

Bergero, R., Girlanda, M., Bello, F., Luppi, A.M., and Perotto,S. (2003) Soil persistence and biodiversity of ericoid myc-orrhizal fungi in the absence of the host plant in a Mediter-ranean ecosystem. Mycorrhiza 13: 69–75.

Bougoure, D.S., Parkin, P.I., Cairney, J.W.G., Alexander, I.J.,and Anderson, I.C. (2007) Diversity of fungi in hair roots ofEricaceae varies along a vegetation gradient. Mol Ecol 16:4624–4636.

Burke, D.J., Dunham, S.M., and Kretzer, A.M. (2008) Molecu-lar analysis of bacterial communities associated with theroots of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) colonized bydifferent ectomycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65:299–309.

Chambers, S.M., Curlevski, N.J.A., and Cairney, J.W.G.

(2008) Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are common root inhabit-ants of non-Ericaceae plants in a south-eastern Australiansclerophyll forest. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65: 263–270.

Colwell, R.K. (2006) EstimateS: statistical estimation ofspecies richness and shared species from samples,version 8. [WWW document]. URL http://purl.oclc.org/estimates.

Fontana, A., and Luppi, A.M. (1966) Funghi saprofiti isolati daectomicorrize. Allionia 12: 39–46.

Girlanda, M., and Luppi-Mosca, A.M. (1995) Microfungi asso-ciated with ectomycorrhizae of Pinus halepensis Mill.Allionia 33: 93–98.

Grünig, C.R., Queloz, V., Sieber, T.N., and Holdenrieder, O.(2008) Dark septate endophytes (DSE) of the Phialo-cephala fortinii s.1. Acephala applanata species complex intree roots: classification, population biology, and ecology.Botany 86: 1355–1369.

Grünig, C.R., Queloz, V., Duó, A., and Sieber, T.N. (2009)Phylogeny of Phaeomollisia piceae Gen. et Sp. nov. a dark,septate, conifer-needle endophyte and its relationships toPhialocephala and Acephala. Mycol Res 113: 207–221.

Hambleton, S., and Sigler, L. (2005) Meliniomyces, a newanamorph genus for root-associated fungi with phyloge-netic affinities to Rhizoscyphus ericae (= Hymenoscyphusericae), Leotiomycetes. Stud Mycol 53: 1–27.

Higgins, K.L., Arnold, A.E., Miadlikowska, J., Sarvate, S.D.,and Lutzoni, F. (2007) Phylogenetic relationships, hostaffinity, and geographic structure of boreal and arctic endo-phytes from three major plant lineages. Mol Phyl Evol 42:543–555.

Hoff, J.A., Kloppenstein, N.B., McDonald, G.I., Tonn, J.R.,Kim, M.-S., Zambino, P.J., et al. (2004) Fungal endophytesin woody roots of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). For Path 34: 255–271.

Katoh, K., Kuma, K., Toh, H., and Miyata, T. (2005) MAFFTversion 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequencealignment. Nucleic Acid Res 33: 511–518.

McArdle, B.H., and Anderson, M.J. (2001) Fitting multivariatemodels to community data: a comment on distance-basedredundancy analysis. Ecology 82: 290–297.

McNabb, R.F.R. (1961) Mycorrhiza in the New Zealand Eri-cales. Aust J Bot 9: 57–61.

Mandyam, K., and Jumpponen, A. (2005) Seeking the elusivefunction of root-colonizing dark septate endophytic fungi.Stud Mycol 53: 173–189.

Melin, E. (1923) Experimentelle Untersuchungen über dieBirken-und Espenmykorrhizen und Ihre Pilzsymbionten.Svensk Bot Tidskr 17: 479–519.

Molina, R., Massicotte, H., and Trappe, J.M. (1992) Specific-ity phenomena in mycorrhizal symbiosis: community-ecological consequences and practical implications. InMycorrhizal Functioning. An Integrative Plant-FungalProcess. Allen, M. (ed.). New York, NY, USA: Chapman &Hall, pp. 357–423.

Morris, M.H., Perez-Perez, M.A., Smith, M.E., and Bledsoe,C.S. (2008a) Multiple species of ectomycorrhizal fungi arefrequently detected on idividual oak root tips in a tropicalcloud forest. Mycorrhiza 18: 375–383.

Morris, M.H., Smith, M.E., Rizzo, D.M., Rejmanek, M., andBledsoe, C.S. (2008b) Contrasting ectomycorrhizal fubgal

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3173

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

communites on the roots of co-occuring oaks (Quercusspp.) in a California woodland. New Phytol 178: 167–176.

Morris, M.H., Perez-Perez, M.A., Smith, M.E., and Bledsoe,C.S. (2009) Influence of host species on ectomycorrhizalcommunities associated with two co-occurring oaks(Quercus spp.) in a tropical cloud forest. FEMS MicrobiolEcol 69: 274–287.

Münzenberger, B., Bubner, B., Wöllecke, J., Sieber, T.N.,Bauer, R., Fladung, M., and Hüttl, R.F. (2009) The ecto-mycorrhizal morphotype Pinirhiza sclerotia is formed byAcephala macrosclerotiorum sp. nov., a close relative ofPhialocephala fortinii. Mycorrhiza (in press): doi: 10.1007/s00572-009-0239-0.

Narisawa, K., Kawamata, H., Currah, R.S., and Hashiba, T.(2002) Suppression of Verticillium wilt in eggplant by somefungal root endophytes. Eur J Plant Pathol 108: 103–109.

Narisawa, K., Hambleton, S., and Currah, R.S. (2007) Het-eroconium chaetospira, a dark septate root endophyteallied to the Herpotrichiellaceae (Chaetothyriales) obtainedfrom some forest soil samples in Canada using bait plants.Mycoscience 48: 274–281.

Neubert, K., Mendgen, K., Brinkmann, H., and Wirsel, S.G.R.(2006) Only a few fungal species dominate highly diversemycofloras associated with the common reed. ApplEnviron Microbiol 72: 1118–1128.

Nilsson, R.H., Ryberg, M., Abarenkov, K., Sjökvist, E., andKristiansson, E. (2009) The ITS region as a target forcharacterization of fungal communities using emergingsequencing technologies. FEMS Microbiol Lett 296:97–101.

O’Brien, H.E., Parrent, J.L., Jackson, J.A., Moncalvo, J.-M.,and Vilgalys, R. (2005) Fungal community analysis bylarge-scale sequencing of environmental samples. ApplEnviron Microbiol 71: 5544–5550.

Piercey, M.M., Thormann, M.N., and Currah, R.S. (2002)Saprobic characteristics of three fungal taxa from ericaleanroots and their association with the roots of Rhododendrongroenlandicum and Picea mariana in culture. Mycorrhiza12: 175–180.

Põldmaa, K. (2000) Generic delimitation of the fungicolousHypocreaceae. Stud Mycol 45: 83–94.

Porter, T.M., Schadt, C.W., Rizvi, L., Martin, A.P., Schmidt,S.K., Scott-Denton, L., et al. (2008) Widespread occur-rence and phylogenetic placement of a soil clone groupadds a prominent new branch to the fungal tree of life. MolPhyl Evol 46: 635–644.

Read, D., Leake, J.R., and Perez-Moreno, J. (2004) Mycor-rhizal fungi as drivers of ecosystem processes in heathlandand boreal forest biomes. Can J Bot 82: 1243–1263.

Ronquist, F., and Huelsenbeck, J.P. (2003) MRBAYES 3:Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bio-informatics 19: 1572–1574.

Rosling, A., Landeweert, R., Lindahl, B.D., Larsson, K.-H.,Kuyper, T.W., Taylor, A.F.S., and Finlay, R.D. (2003) Ver-tical distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungal taxa in a podzolsoil profile. New Phytol 159: 775–783.

Schulz, B.J.E., Boyle, C.J.C., and Sieber, T.N. (2006) Micro-bial Root Endophytes. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Selosse, M.-A., Setaro, S., Glatard, F., Richard, F., Urcelay,C., and Weiss, M. (2007) Sebacinales are common myc-

orrhizal associates of Ericaceae. New Phytol 174: 864–878.

Sharon, M., Kuninaga, S., Hyakumachi, M., and Sneh, B.(2006) The advancing identifiction and classification ofRhizoctonia spp. using molecular and biotechnologicalmethods compared with the classical anastomosis group-ing. Mycoscience 47: 299–316.

Sieber, T.N., and Grünig, C.R. (2006) Biodiversity of fungalroot-endophyte communities and populations, in particularof the dark septate endophyte Phialocephala fortinii s.l. InMicrobial Root Endophytes. Schulz, B.J.E., Boyle, C.J.C.,and Sieber, T.N. (eds). Berlin, Germany: Springer, pp.107–132.

Smith, M.E., Douhan, G.W., and Rizzo, D.M. (2007) Ectomy-corrhizal community structure in a xeric Quercus woodlandbased on rDNA sequence analysis of sporocarps andpooled roots. New Phytol 174: 847–863.

Sprent, J.L., and James, U.K. (2007) Legume evolution:where do nodules and mycorrhizas fit in? Plant Physiol144: 575–581.

Stamatakis, A., Hoover, P., and Rougemont, J. (2008) A rapidbootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web-servers. Syst Biol75: 758–771.

Summerbell, R.C. (1989) Microfungi associated with the myc-orrhizal mantle and adjacent microhabitats within the rhizo-sphere of black spruce. Can J Bot 67: 1085–1095.

Summerell, B.A., and Leslie, J.F. (2004) Genetic diversityand population structure of plant-pathogenic species in thegenus Fusarium. In Plant Microbiology. Gillings, M., andHolmes, A. (eds). Oxford, UK: Garland Science/BIOS Sci-entific Publisher, pp. 207–223.

Tedersoo, L., Kõljalg, U., Hallenberg, N., and Larsson, K.-H.(2003) Fine scale distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungi androots across substrate layers including coarse woodydebris in a mixed forest. New Phytol 159: 153–165.

Tedersoo, L., Suvi, T., Larsson, E., and Kõljalg, U. (2006)Diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungiin a wooded meadow. Mycol Res 110: 734–748.

Tedersoo, L., Pellet, P., Kõljalg, U., and Selosse, M.-A.(2007) Parallel evolutionary paths to mycoheterotrophy inunderstorey Ericaceae and Orchidaceae: ecological evi-dence for mixotrophy in Pyroleae. Oecologia 151: 206–217.

Tedersoo, L., Suvi, T., Jairus, T., and Kõljalg, U. (2008a)Forest microsite effects on community composition of ecto-mycorrhizal fungi on seedlings of Picea abies and Betulapendula. Environ Microbiol 10: 1189–1201.

Tedersoo, L., Jairus, T., Horton, B.M., Abarenkov, K., Suvi,T., Saar, I., and Kõljalg, U. (2008b) Strong host preferenceof ectomycorrhizal fungi in a Tasmanian wet sclerophyllforest as revealed by DNA barcoding and taxon-specificprimers. New Phytol 180: 479–490.

Tedersoo, L., Gates, G., Dunk, C., Lebel, T., May, T.W.,Kõljalg, U., and Jairus, T. (2009) Establishment of ectomy-corrhizal fungal community on isolated Nothofaguscunninghamii seedlings regenerating on dead wood inAustralian wet temperate forests: does fruit-body typematter? Mycorrhiza (in press) doi: 10.1007/s00572-009-0244-3.

Urban, A., Puschenreiter, M., Strauss, J., and Gorfer, M.(2008) Diversity and structure of ectomycorrhizal and

3174 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

co-associated fungal communities in a serpentine soil.Mycorrhiza 18: 339–354.

Usuki, F., and Narisawa, K. (2005) Formation of structuresresembling ericoid mycorrhizas by the root endo-phytic fungus Heteroconium chaetospira within roots ofRhododendron obtusum var. kaempferi. Mychorriza 15:61–64.

Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Baldauf, S.L., Leyval, C., Straczek,J., and Young, J.P.W. (2002) Extensive fungal colonizationin plant roots. Science 295: 2051.

Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Ridgway, P., Watson, I.J., Fitter,A.H., and Young, J.P.W. (2003) Co-existing grass specieshave distinctive arbuscular mycorrhizal communities. MolEcol 12: 3085–3095.

Vrålstad, T., Schumacher, T., and Taylor, A.F.S. (2002) Myc-

orrhizal synthesis between fungal strains of the Hymenos-cyphus ericae aggregate and potential ectomycorrhizaland ericoid hosts. New Phytol 153: 143–152.

Wang, Z., Johnston, P.R., Takamatsu, S., Spatafora, J.W.,and Hibbett, D.S. (2006) Toward a phylogenetic classifica-tion of the Leotiomycetes based on rDNA data. Mycologia98: 1066–1076.

Wright, S.H.A., Berch, S.M., and Berbee, M.L. (2009) Theeffect of fertilization on the below-ground diversity andcommunity composition of ectomycorrhizal fungi associ-ated with western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla). Mycor-rhiza 19: 267–276.

Zare, R., and Gams, W. (2008) A revision of the Verticilliumfungicola species complex and its affinity with the genusLecanicillium. Mycol Res 112: 811–824.

Appendix 1

Characterization of the primers (in bold) designed for the identification of Ascomycota in this study. Multiple sequence alignmentswith target and non-target taxa are indicated.

ITS4-Sord (calculated TM = 56°C); specific to SordariomycetesPrimer 5′-CCCGTTCCAGGGAACTC-3′Sordariomycetes (45) *****************Ascomycota other (101) **Y******A**R***TBasidiomycota (95) *********A*AR***TPlants (6) ***C********G***TLA-W (calculated TM = 58°C); specific to AscomycotaPrimer 5′-CTTTTCATCTTTCGATCACTC-3′Ascomycota (incl. SCGI*) (98) *********************

Pachyella (2) ****************T****Heterobasidiomycetes, Sebacinales (92) *************CC****GG

Cantharellus cibarius (1) *************CC*TG*GGSistotrema confluens (1) *************CC**G*GGTulasnella (2) ******C******CC****GG

Plants (6) *************CC**G*GGLR3-Asc (calculated TM = 57°C); specific to PezizomycotinaPrimer 5′-CACYTACTCAAATCCAAGCG-3′Ascomycota [75; incl. Pezizales (26)] ***Y****************

Pezizales (18) ***Y***********T**A*Orbiliales (1) *T*A************TC**SCGI* (2) *T*T******C****TTCG*

Basidiomycota (62) ***TAC*K*NG*WS*G**RYPinaceae (2) ***GC****G**C**T**GCAngiosperms (4) ***W*****G*****T**TCNOTE: This primer is not recommended for further useLR6-Sord (calculated TM = 58°C); specific to SordariomycetesPrimer 5′-GTTTGAGAATGGATGAAGGC-3′Sordariomycetes (40) ********************Ascomycota (other) (60) **********A*G*T****WBasidiomycota (70) **********A*G*T****WPlants (6) **********A*G*CG***GLR6-LS (calculated TM = 58°C); specific to Leotio- and Sordariomycetes.Primer 5′-AAAATGGCCCACTAGTGTTG-3′Sordariomycetes, Leotiomycetes (60) ********************Ascomycota (other) (40) ****************AAC*Basidiomycota (70) ***************A**CTPlants (6) *************T*G*G**LR6-Asc (calculated TM = 58°C); specific to Ascomycota; not experimentally testedPrimer component #1 5′-AAAATGGCCCACTAGTAACG-3′Primer component #2 +AAAATGGCCCACTAGTGTTGSordariomycetes, Leotiomycetes (60) ****************GTT*Ascomycota (other) (40) ****************AAC*Basidiomycota (70) ***************A**CTPlants (6) *************T*G*G**

*CSGI, Soil Clone Group I of the basal Ascomycota (cf. Porter et al., 2008).

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3175

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

Ap

pen

dix

2

Mol

ecul

arid

entifi

catio

nan

dfr

eque

ncy

ofec

tom

ycor

rhiz

a-as

soci

ated

asco

myc

etes

.

Spe

cies

Isol

ate

UN

ITE

acce

ssio

nP

utat

ive

lifes

tyle

Bes

tfu

ll-le

ngth

ITS

sequ

ence

mat

chR

elat

ive

freq

uenc

yof

indi

vidu

als

Bes

tm

atch

ing

isol

ate(

s)%

ID

Mt.

Fie

ldW

arra

Euc

alyp

tus

regn

ans

(n=

49)

Not

hofa

gus

cunn

ingh

amii

(n=

25)

Pom

ader

risap

etal

a(n

=74

)

For

est

floor

soil

(n=

80)

Dea

dw

ood

(n=

23)

Hel

otia

les

sp00

6L3

187

UD

B00

4100

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

6278

17O

idio

dend

ron

mai

usA

F06

2798

97.9

96.1

00

40

0

Hel

otia

les

sp00

7L3

097b

UD

B00

4101

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

6278

17O

idio

dend

ron

mai

usA

F06

2798

99.1

96.4

42

200

0

Hel

otia

les

sp00

8L3

127a

UD

B00

4105

End

ophy

teD

erm

eavi

burn

iAF

1411

6385

.36

00

20

Hel

otia

les

sp00

9L3

136b

UD

B00

4107

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

2682

08P

ezic

ula

cinn

amom

eaA

F14

1186

97.7

97.1

00

10

0

Hel

otia

les

sp01

1L3

260

UD

B00

4108

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

mai

usA

Y62

4308

89.9

01

00

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

012

L329

2cU

DB

0041

09E

ndop

hyte

Cla

doph

ialo

phor

am

inut

issi

ma

EF

0163

8591

.40

01

00

Hel

otia

les

sp01

3L3

325c

UD

B00

4110

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

2791

89Le

ptod

ontid

ium

elat

ius

AY

8055

6996

.692

.03

05

00

Hel

otia

les

sp01

6L3

385S

UD

B00

4111

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8796

.012

00

00

Hel

otia

les

sp01

7L3

395

UD

B00

4113

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8795

.92

00

00

Hel

otia

les

sp01

8L3

219

UD

B00

4115

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8796

.41

10

00

Hel

otia

les

sp01

9L3

362

UD

B00

4116

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8794

.91

00

00

Hel

otia

les

sp02

0L3

563S

UD

B00

4117

End

ophy

teLe

ohum

icol

am

inim

aA

Y70

6329

89.0

00

00

1H

elot

iale

ssp

023

L318

5fU

DB

0041

18E

ndop

hyte

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y12

9285

92.5

00

20

0H

elot

iale

ssp

024

L335

5U

DB

0041

19E

ndop

hyte

Epa

cris

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usA

Y62

7809

Lept

odon

tidiu

msp

.D

Q06

9035

99.2

92.7

00

10

0

Hel

otia

les

sp02

5L3

532

UD

B00

4120

End

ophy

teTs

uga

EcM

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usD

Q49

7950

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y12

9285

94.3

92.8

00

00

1

Hel

otia

les

sp02

6L3

569

UD

B00

4121

End

ophy

teTs

uga

EcM

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usD

Q49

7943

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y78

1230

97.5

93.7

10

00

1

Hel

otia

les

sp02

7L3

560

UD

B00

4123

End

ophy

teLe

ptod

ontid

ium

sp.

DQ

0690

3593

.70

00

01

Hel

otia

les

sp02

8L3

508

UD

B00

4124

End

ophy

teLe

ptod

ontid

ium

sp.

DQ

0690

3593

.10

00

01

Hel

otia

les

sp02

9L3

503

UD

B00

4125

End

ophy

teH

umic

ola

sp.

DQ

0690

2593

.10

00

34

Hel

otia

les

sp03

0L3

570

UD

B00

4126

Sap

robe

Hol

way

am

ucid

aD

Q25

7357

100.

00

00

01

Hel

otia

les

sp03

1L3

283

UD

B00

4127

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

2791

89Le

ptod

ontid

ium

sp.

DQ

0690

3399

.895

.60

20

00

Hel

otia

les

sp03

2L3

558

UD

B00

4129

End

ophy

teC

adop

hora

finla

ndic

aE

F09

3179

91.1

00

01

1H

elot

iale

ssp

033

L356

5U

DB

0041

30E

ndop

hyte

Mel

inio

myc

esva

riabi

lisA

J430

148

99.6

00

00

1H

elot

iale

ssp

034

L354

8U

DB

0041

31E

ndop

hyte

plan

tlit

ter

asso

ciat

edfu

ngus

DQ

9147

30S

piro

spha

era

beve

rwijk

iana

EF

0292

0195

.088

.41

00

01

Hel

otia

les

sp03

5L3

287

UD

B00

4133

End

ophy

teC

allu

naro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

DQ

3091

34S

cler

opez

icul

aal

nico

laA

F14

1168

.199

.489

.90

02

00

Hel

otia

les

sp03

6L3

583f

UD

B00

4134

End

ophy

teR

hodo

dend

ron

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usA

Y69

9684

Hum

icol

asp

.D

Q06

9025

97.7

93.7

01

03

0

Hel

otia

les

sp03

7L3

705

UD

B00

4136

End

ophy

teLe

ptod

ontid

ium

elat

ius

AY

1292

8592

.90

01

10

Hel

otia

les

sp03

8L3

739

UD

B00

4138

End

ophy

teE

pacr

idro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

2791

89Le

ptod

ontid

ium

elat

ius

AY

1292

8597

.691

.80

61

141

Hel

otia

les

sp04

0L3

388

UD

B00

4141

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

chla

myd

ospo

ricum

AF

0627

8994

.81

00

00

3176 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

Hel

otia

les

sp04

1L3

590

UD

B00

4142

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

2682

08P

ezic

ula

cinn

amom

eaA

F14

1186

97.7

97.1

00

12

0

Hel

otia

les

sp04

3L3

129b

fU

DB

0041

43E

ndop

hyte

Cad

opho

rasp

.AY

3715

1387

.41

00

00

Cap

nodi

ales

sp04

6L3

390

UD

B00

4144

Pla

ntpa

rasi

teM

ycos

phae

rella

cann

abis

AY

1525

49.1

96.8

10

00

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

047

L320

0U

DB

0041

45E

ndop

hyte

Cla

doph

ialo

phor

ach

aeto

spira

EU

0354

04.1

95.2

00

20

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

048

L301

7bU

DB

0041

47E

ndop

hyte

Cla

doph

ialo

phor

ach

aeto

spira

EU

0354

04.1

91.3

00

00

0P

eziz

ales

sp04

9L3

240

UD

B00

4149

Sap

robe

Bet

ula

EcM

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usA

B21

8200

94.2

01

10

0S

orda

riale

ssp

050

L334

1U

DB

0041

50S

apro

beC

haet

omiu

msp

AM

2624

01.1

83.9

00

10

0H

elot

iale

ssp

051

L335

5U

DB

0041

51S

apro

beLe

otia

lubr

ica

AY

1445

4399

.80

02

00

Con

ioch

aeta

les

sp05

2L3

702

UD

B00

4153

Sap

robe

Lecy

thop

hora

sp.A

Y21

9880

88.1

00

00

2E

urot

iale

ssp

053

L307

3U

DB

0041

54S

apro

beP

enic

illiu

mth

omii

DQ

1328

26.1

99.8

10

00

1E

urot

iale

ssp

054

L333

4U

DB

0041

55S

apro

beP

enic

illiu

mro

seop

urpu

reum

AF

0334

15.1

98.4

00

20

0H

ypoc

real

essp

055

L305

0U

DB

0041

56S

apro

beP

hial

emon

ium

aff.

dim

orph

ospo

rum

AY

1883

7181

.10

01

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp05

6L3

161e

UD

B00

4157

Myc

opar

asite

Hyp

ocre

opsi

ssp

EU

0731

98.1

88.4

00

10

0S

orda

riale

ssp

057

L318

7U

DB

0041

58C

opro

phile

Pod

ospo

radi

dym

aA

Y99

9127

80.9

00

10

0H

ypoc

real

essp

058

L353

7U

DB

0041

59In

sect

para

site

Cor

dyce

psin

egoe

nsis

AB

0273

68.1

82.7

00

00

1S

orda

riale

ssp

059

L354

8U

DB

0041

60S

apro

beS

oilf

ungu

sE

U55

4812

91.8

00

00

1C

apno

dial

essp

062

L336

9bU

DB

0041

61S

apro

beC

lado

spor

ium

ossi

frag

iEF

6793

8210

0.0

10

03

1H

elot

iale

ssp

063

L366

4aU

DB

0041

62E

ndop

hyte

Scl

erop

ezic

ula

alni

cola

AF

1411

6991

.00

00

20

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp06

4L3

388

UD

B00

4163

Sap

robe

Clo

nost

achy

sca

ndel

abru

mA

F21

0668

95.6

10

10

0S

orda

riale

ssp

066

L301

8U

DB

0041

65E

ndop

hyte

Lith

ocar

pus

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usD

Q27

3344

Aqu

atic

ola

hong

kong

ens

AF

1771

5689

.871

.10

02

00

Cha

etot

hyria

les

sp06

7L3

598m

UD

B00

4166

End

ophy

teC

lado

phia

loph

ora

min

utis

sim

aE

F01

6385

92.0

00

02

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

068

L360

9bU

DB

0041

67S

apro

beC

haet

osph

aeria

talb

otii

DQ

9146

6698

.00

00

20

Hel

otia

les

sp07

0L3

637m

UD

B00

4168

End

ophy

teLe

ptod

ontid

ium

sp.

DQ

0690

3395

.60

00

20

Hel

otia

les

sp07

1L3

609s

UD

B00

4169

End

ophy

teR

oesl

eria

subt

erra

nea

EF

0603

09.1

85.3

00

01

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

073

L372

7U

DB

0041

70S

apro

beD

acty

laria

appe

ndic

ulat

aA

Y26

5339

92.0

00

01

0E

urot

iale

ssp

074

L370

5bU

DB

0041

71S

apro

beP

enic

illiu

min

dicu

mA

Y74

2699

83.6

00

01

0C

haet

othy

riale

ssp

075

L366

9U

DB

0041

72S

apro

beC

haet

osph

aeria

verm

icul

ario

ides

AF

1785

5093

.30

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp07

6L3

574S

UD

B00

4173

End

ophy

teC

allu

naro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

DQ

3091

26C

lado

phia

loph

ora

min

utis

sim

aE

F01

6385

80.7

83.5

00

01

0

Cha

etot

hyria

les

sp07

7L3

640b

UD

B00

4174

End

ophy

teE

xoph

iala

xeno

biot

ica

EF

0254

0810

0.0

00

01

0S

orda

riale

ssp

078

L364

8aU

DB

0041

75S

apro

beM

yrm

ecrid

ium

schu

lzer

iEU

0417

7588

.00

00

10

Art

honi

ales

sp07

9L3

744

UD

B00

4176

Sap

robe

Ope

grap

hava

riaA

F13

8838

82.4

00

01

0H

ypoc

real

essp

081

L367

3cU

DB

0041

77S

apro

beTr

icho

derm

avi

ride

X93

979

99.6

00

03

0H

ypoc

real

essp

082

L334

5U

DB

0041

78P

lant

para

site

Cyl

indr

ocar

pon

sp.

DQ

9146

7098

.40

01

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp08

3L3

350

UD

B00

4179

Unk

now

nV

ertic

illiu

msp

.D

Q91

4739

97.6

00

10

0H

ypoc

real

essp

084

L302

9U

DB

0041

80M

ycop

aras

iteLe

cani

cilli

umsp

.AB

3603

6898

.60

01

00

Ple

ospo

rale

ssp

085

L372

5U

DB

0041

81S

apro

beE

pico

ccum

nigr

umE

U52

9998

97.1

00

01

0H

ypoc

real

essp

086

L335

2U

DB

0041

82P

lant

para

site

Neo

nect

riara

dici

cola

DQ

1328

4699

.80

06

30

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp08

7L3

093a

UD

B00

4183

Inse

ctpa

rasi

teC

ordy

ceps

bass

iana

DQ

6798

9799

.20

10

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp08

8L3

070a

UD

B00

4184

Sap

robe

Myr

othe

cium

verr

ucar

iaA

J301

999

88.6

10

00

0H

elot

iale

ssp

089

L357

7U

DB

0041

85E

ndop

hyte

Cal

luna

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usD

Q30

9162

Pse

udae

gerit

avi

ridis

EF

0292

3598

.390

.90

00

10

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp09

0L3

184p

UD

B00

4186

Pla

ntpa

rasi

teN

eone

ctria

radi

cico

laA

J875

331

85.0

00

10

0H

ypoc

real

essp

091

L332

9U

DB

0041

87S

apro

beC

lono

stac

hys

cand

elab

rum

AF

2106

6876

.70

01

00

Hel

otia

les

sp09

2L3

364

UD

B00

4188

End

ophy

teS

cler

opez

icul

aal

nico

laA

F14

1168

91.4

10

00

0H

elot

iale

ssp

093

L359

5U

DB

0041

89E

ndop

hyte

Hum

icol

asp

.D

Q06

9025

90.8

00

01

0H

ypoc

real

essp

094

L309

0eU

DB

0041

90M

ycop

aras

iteM

ycog

one

pern

icio

saE

U38

0317

88.6

02

00

0H

elot

iale

ssp

096

L358

3sU

DB

0041

92E

ndop

hyte

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y78

1230

87.4

00

01

0S

orda

riale

ssp

097

L304

2aU

DB

0041

93S

apro

beC

epha

loth

eca

sulfu

rea

AB

2781

9479

.30

01

00

Ectomycorrhiza-associated ascomycetes 3177

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178

Ap

pen

dix

2co

nt.

Spe

cies

Isol

ate

UN

ITE

acce

ssio

nP

utat

ive

lifes

tyle

Bes

tfu

ll-le

ngth

ITS

sequ

ence

mat

chR

elat

ive

freq

uenc

yof

indi

vidu

als

Bes

tm

atch

ing

isol

ate(

s)%

ID

Mt.

Fie

ldW

arra

Euc

alyp

tus

regn

ans

(n=

49)

Not

hofa

gus

cunn

ingh

amii

(n=

25)

Pom

ader

risap

etal

a(n

=74

)

For

est

floor

soil

(n=

80)

Dea

dw

ood

(n=

23)

Con

ioch

aeta

les

sp09

8L3

050a

UD

B00

4194

Sap

robe

Leaf

litte

ras

soci

ated

fung

usE

F15

9553

Con

ioch

aeta

sp.A

M26

2406

98.5

90.7

00

10

0

Hel

otia

les

sp09

9L3

585

UD

B00

4195

End

ophy

teS

oilf

ungu

sE

F43

4152

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y80

5569

94.2

94.2

00

02

0

Pez

izal

essp

100

L311

9eU

DB

0041

96S

apro

beS

trum

ella

cory

neoi

dea

AF

4850

6993

.21

00

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp10

1L3

176a

UD

B00

4197

Unk

now

nV

ertic

illiu

mle

ptob

actr

umA

B21

4657

92.0

00

10

0H

elot

iale

ssp

102

L320

8eU

DB

0041

98E

ndop

hyte

Phi

alop

hora

sp.

DQ

0690

4698

.50

10

00

Leca

nora

les

sp10

3L3

306

UD

B00

4199

Sap

robe

Ste

reoc

aulo

nal

pinu

mD

Q21

9308

81.1

00

10

0H

elot

iale

ssp

104

L332

9U

DB

0042

00E

ndop

hyte

Epa

cris

root

-ass

ocia

ted

fung

usA

Y62

7817

Oid

iode

ndro

nm

aius

AY

6243

0895

.594

.10

01

00

Hel

otia

les

sp10

9L3

382

UD

B00

4201

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8795

.81

00

00

Cha

etot

hyria

les

sp11

0L3

101e

UD

B00

4202

Sap

robe

Cha

etos

phae

riaac

utat

aA

F17

8553

85.6

01

00

0H

elot

iale

ssp

111

L359

1U

DB

0042

03E

ndop

hyte

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y78

1230

92.4

00

02

1H

elot

iale

ssp

112

L353

9U

DB

0042

04E

ndop

hyte

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y78

1230

90.7

00

00

1X

ylar

iale

ssp

113

L358

9U

DB

0042

05S

apro

beM

icro

doch

ium

niva

leA

B27

2124

99.4

00

01

0H

elot

iale

ssp

114

L359

8SU

DB

0042

06E

ndop

hyte

Leoh

umic

ola

verr

ucos

aA

Y70

6325

89.9

00

01

0H

elot

iale

ssp

115

L363

5U

DB

0042

07E

ndop

hyte

Cad

opho

rafin

land

ica

AY

2490

7495

.30

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp11

7L3

678f

UD

B00

4208

End

ophy

teP

yren

opez

iza

gent

iana

eU

DB

0030

7590

.50

00

10

Sor

daria

les

sp11

8L3

685

UD

B00

4209

Sap

robe

Glo

eotin

iate

mul

enta

DQ

2356

9798

.50

00

10

Sor

daria

les

sp11

9L3

691f

UD

B00

4210

Sap

robe

Fim

etar

iella

rabe

nhor

stii

AM

9217

1781

.90

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp12

0L3

716

UD

B00

4211

End

ophy

teLe

ptod

ontid

ium

elat

ius

AY

1292

8581

.10

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp12

1L3

710

UD

B00

4212

End

ophy

teE

pacr

isro

ot-a

ssoc

iate

dfu

ngus

AY

6691

37Le

ptod

ontid

ium

elat

ius

AY

7812

3097

.192

.90

00

10

Cap

nodi

ales

sp12

2L3

261

UD

B00

4213

Sap

robe

Cla

dosp

oriu

mcl

ados

porio

ides

AF

1777

3690

.40

11

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp12

5L3

675

UD

B00

4216

Sap

robe

Tric

hode

rma

aspe

rellu

mD

Q09

3705

99.6

00

01

0H

elot

iale

ssp

126

L359

8fU

DB

0042

17E

ndop

hyte

Unc

ultu

red

soil

fung

usE

F43

4152

Lept

odon

tidiu

mel

atiu

sA

Y80

5569

95.2

95.2

00

01

0

Hel

otia

les

sp12

7L3

636

UD

B00

4218

End

ophy

teLa

nzia

huan

gsha

nica

DQ

9864

8480

.80

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp12

8L3

615S

UD

B00

4219

End

ophy

teO

idio

dend

ron

pilic

ola

AF

0627

8796

.10

00

10

Hel

otia

les

sp13

0L2

620L

UD

B00

4240

End

ophy

teB

otry

otin

iafu

ckel

iana

AY

5446

51*

99.0

00

00

1H

ypoc

real

essp

131

L327

8aU

DB

0042

21M

ycop

aras

iteH

ypom

yces

aura

ntiu

sA

B37

4290

74.9

01

00

0H

ypoc

real

essp

132

L320

7nU

DB

0042

22M

ycop

aras

iteH

ypom

yces

chlo

rinig

enus

AF

0548

6681

.10

10

00

Hyp

ocre

ales

sp13

3L3

195s

UD

B00

4223

Sap

robe

Soi

lfun

gus

AF

5048

33P

aeci

lom

yces

carn

eus

AB

2583

6999

.889

.90

01

00

Leca

nici

llium

flavi

dum

L370

9U

DB

0042

24M

ycop

aras

iteLe

cani

cilli

umfla

vidu

mE

F64

1878

99.8

83

39

0

*Bas

edon

28S

rDN

Am

atch

.

3178 L. Tedersoo et al.

© 2009 Society for Applied Microbiology and Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Environmental Microbiology, 11, 3166–3178