Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

Transcript of Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

1/36

Ileana Parvu (éd.)

O B J E T S E N P R O C È SO B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S SAprès la dématérialisation de l’art / After the Dematerialisation of Art

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

2/36

CopyrightMētisPresses, © 2012Atelier 248, rte des Acacias 43, CH – 1227 Genèvehttp://[email protected] et traduction, même partielles, interdites.Tous droits réservés pour tous les pays.

SoutienPublié avec l'appuidu Fonds national suisse de la recherche scientifique.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

3/36

Table

IntroductionObjets en procès11Objects in ProgressIleana Parvu21

Dématérialisations/Dematerialisations

In Search of the Insignificant. Street Work, ‘Borderline’ Art andDematerialisationAnna Dezeuze35Le lieu de mémoireor the (Im)memorability of SculpturePenelope Curtis65

À l'épreuve de l'espace/The Trial of SpaceOutside/Inside. Public and Private in the Work of Rachel WhitereadSue Malvern85L'espace des chaussettes.Socks(1995) de Gabriel Orozco dans leprojetMigrateursIleana Parvu103

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

4/36

Sculpture et performance/Sculpture and Performance

Subject Formation and Spectacle Critique in Paul McCarthy's WorkSebastian Egenhofer125Test Room(1999) de Mike Kelley. Une chambre d'expérimentationde la sculptureSylvie Coëllier143

Matériaux/MaterialsFolioZoë Sheehan Saldaña161Matière, mémoire etsampling. Questions à propos des sculpturesde Dario RobletoDario Gamboni177

AnnexesContributeurs/Contributors201Résumés/Abstracts204Crédits207

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

5/36

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

6/36

35

In Search of the InsignificantStreet Work, ‘Borderline’ Art and Dematerialisation1

Anna Dezeuze

The minimum requirement of aesthetic iden-tity in a work of art has been legibility as anobject, a degree of compactness (so that theobject is united, composed, stable). In the1960s, a number of non-compact art forms(diffuse or nearly imperceptible) have prolif-erated.

ALLOWAY[1969: 207]

Had you walked on Fourteenth, Grand,Broome, Spring, or Prince Streets a few weeksago, you might not have been aware thatStreet Workswere in progress – some sevenhundred of them.

GRUEN[1969]

Though Lawrence Allowaydoes not mention them in his 1969 articleon ‘The Expanding and Disappearing Work of Art’, few events seem toexemplify his concern with ‘non-compact art forms’ as well as theseries ofStreet Worksinitiated in New York that same year. Indeed,

many of the Street Works on show in May 1969 were so ‘diffuse’and‘nearly imperceptible’ that the seven hundred figure quoted by thereviewer is impossible to verify. The figure corresponds in fact to thenumber of invitations sent out by the organisers ofStreet Works III–poets John Perreault and Hannah Weiner, and painter Marjorie Strider– who would not have been able to confirm themselves how manyartists responded to their announcement, which specified only aplace (the area delimited by Grand, Prince, Greene and Woosterstreets in New York), date, and time (25 May, 9 pm-12 midnight). Inthis kind of event, remarked Perreault, it ‘was difficult to tell whatobjects and what activities were or were not Street Works’[PERREAULT1969f]. Weaving together a discussion of Alloway's essay and a

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

7/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

study of the sixStreet Worksevents which took place between March1969 and March 1970 allows us to trace an alternative narrative of the ‘dematerialisation of the art object’, first delineated by LucyLippard and John Chandler in 1968. I will also demonstrate howAlloway's focus on the ‘interface with other things’ – rather than themovement of reduction or subtraction suggested by Lippard andChandler's definition of ‘ultra-conceptual’ art – intersects not onlywith Jack Burnham's contemporary definition of a ‘systems aesthet-ics’, but also with the concept of ‘borderline’ art outlined by Fluxusartist George Brecht in the early 1960s. By bringing together this set

of practices and these theoretical texts, I will map out a genealogy for‘borderline’practices in conceptual art since the 1960s, and developa critical vocabulary to describe this form of ‘non-compact’ work.

Systems, Boundaries, Borderline Art

‘All legitimate art deals with limits. Fraudulent art feels it has nolimits. […] [T]he trick is to locate those elusive limits’ [SMITHSON1969: 90]. Robert Smithson's comment, in a June 1969 interview,reveals a concern shared by both artists and theorists of conceptu-al art during this period. As Lippardretrospectively recalled, much of the discussion at the time ‘had to do with boundaries – thoseimposed by conventional art definitions and contexts, and thosechosen by the artists to make points about the new, autonomouslines they were drawing’[LIPPARD1993: XX]. Boundaries were certain-ly crucial to Alloway's definition of ‘interfaces’ in his 1969 essay on‘The Expanding and Disappearing Work of Art’: the first meaning of ‘interface’according to him was ‘a surface forming a common bound-ary of two bodies or two spaces’ – in this case, the ‘problematicboundaries of art's zone and our space’ [ALLOWAY1975: 193]. Thesecond meaning of the term ‘interface’ chosen by Alloway is ‘thechangeover from one system of communication to another’, with ref-erence to the proliferation of different media in the 1960s, whetherperformance, Land Art, language, documentation and photography.The term ‘system’ had been foregrounded by Burnham in his 1968

analysis of similar developments, in which according to him ‘art doesnot reside in material entities, but in relations between people andbetween people and the components of their environment’ [BURNHAM1968: 31]. As he explains, his proposed ‘system approach […] deals

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

8/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 37

in a revolutionary fashion with the larger problem of boundary con-cepts’ [BURNHAM1968: 32]. Both Alloway and Burnham seemed toagree that contemporary art practices challenged the formalistmodel of the self-contained, autonomous artwork. Burnham soughtto define this move away from the ‘finite, unique work of high art’ asa shift to systems rather than objects, whereas Alloway contrastedthe formalist approach ‘that aims to distil and purify’ art with ‘onethat studies the expansion and connectivity of art’ [ALLOWAY1975b:193].Unsurprisingly, both theories mentioned the non-sites of Smithson, in

which the artist sought to ‘locate the elusive limits’of art, by exhibitingrock and earth samples in the gallery, alongside a map documentingtheir exact geographical origin. In fact, Allowaydevotes a whole essayto the artist's work in his study of ‘art and interface’. While Burnhampoints to the ‘environmental sensibility’ at the heart of Smithson'smove ‘away from the preciousness of the work of art’, Allowaypraiseshis ‘art of expanding thresholds’ [BURNHAM1968: 34; ALLOWAY1973:229]. Smithson's work and writing perform, according to him, a shift‘from an art of autonomous objects to an art penetrating the world andpenetrated by sign systems’ [ALLOWAY1973: 229-230].Perhaps more surprising is the significance of Allan Kaprow's mid- tolate-1960s works and writings for both Burnham and Alloway.Kaprow, traditionally associated with the late-1950s happenings, hadstarted to develop in the late 1960s more ‘elegant’ events – which hewould come to designate as ‘activities’. Alloway mentions, for exam-ple,Pose, one of the 1969Six Ordinary Happenings, which involves:

Carrying chairs through the citySitting down here and therePhotographedPix left on spotGoing on.2

The authors single out three crucial characteristics of the ‘activities’that Kaprow was developing and theorising at the time. Firstly, asBurnham notes, the new simplified format of Kaprow's recent workallows for a ‘participatory aesthetic’; this is why Alloway speaks of the ‘mode of intimacy’ that they require [BURNHAM1968: 35; ALLOWAY

1969: 207]. Secondly, these participatory activities ‘include experi-ence of duration as part of their format’; Alloway quotes Kaprow'sdefinition of their ‘variable and discontinuous time’, and concludesthat they thus demand a new ‘aesthetics of temporal succession’

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

9/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

[ALLOWAY1975a: 197]. Finally, Kaprow's activities, which take place inrural as well as urban settings, are characterised by their ‘geographi-cal expansiveness and mobility’, according to Burnham [1968: 35].Alloway agrees: unlike the early happenings, Kaprow's mid-1960sactivities display a ‘diffuseness’ which goes ‘beyond any form of compactness’ [ALLOWAY1975a: 196]. Thus, Burnham considers the‘internal logic’of Kaprow's activities and the ‘indivisibility’they estab-lish ‘between themselves and everyday affairs’ as stemming from‘the same considerations that have crystallised the systemsapproach to environmental situations’ [BURNHAM1968: 35].

If Lippardand Chandler refer to Smithson's work in their 1968 essay,no mention is made of Kaprow's practice or writing. One artist theydo mention in passing, however, was closely associated with Kaprow,in particular in Alloway's account: George Brecht, a friend of Kaprow'swho was involved in the loose association of artists known as Fluxus[LIPPARDand CHANDLER1968: 264]. In fact, the first two entries inLippard'sSix Yearscompendium refer to Brecht's scores andKaprow's 1966 book on Assemblage,E nvironments and Happenings,thus suggesting their foundational role in the development of dema-terialised art practices. The first listed work in the book, dated 1961,is Brecht's score forThree AqueousE vents, which reads:

• ice• water• steam

Writing in Assemblage,E nvironments and Happenings, Kaprowsinglesout Brecht's scores as containing ‘the most radical potential in all of thework discussed in this book’[KAPROW1966: 195]. For Kaprow, this rad-

ical potential lies in the fact that they place on the performer the soleresponsibility ‘to make something of the situation or not’. It is in thissense that they relate to Kaprow's activities at the time, whose ‘spread’in terms of ‘structure’, ‘duration’and ‘area’was noted by both Burnhamand Alloway. According to the latter, the kind of spread evident inKaprow’s and Brecht's work ‘raises undiscussed problems about thelimits’ of the artwork as a system, and the new modes of ‘recognition’that they invite [ALLOWAY1975a: 196]. Alloway cites Brecht's scores asdemanding the same ‘mode of intimacy’ as Kaprow's activities. If bothKaprow's and Brecht's works are ‘known only incompletely to thosetaking part’, however, Brecht's scores are even more radical, as theyare, ‘to many, imperceptible’[ALLOWAY1969: 208; ALLOWAY1975a: 196].

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

10/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 39

Crucially, imperceptibility lay at the heart of Brecht's 1961 definition,at the time of his first event scores, of what he called ‘“borderline”art’. In a 1961 essay, subsequently published in the first issue of theFluxus magazinecc VTRE , Brechtdefined ‘borderline’ art as ‘an art atthe point of imperceptibility. Sounds barely heard, sights barely dis-tinguished’[BRECHT1964: 2]. In brackets, Brecht added: ‘It should bepossible to miss it completely.’One of the event scores interspersedin his essay isThree AqueousE vents; another score, forThree ChairE vents, reads:

• Sitting on a white chair.

Occurrence.• On (or near) a black chair.Occurrence.• Yellow chair.Occurrence.

In its slightly different final version, the score forThree ChairE ventswas in fact realised at the exhibitionE nvironments, Situations,Spaces (Six Artists)at the Martha Jackson Gallery in March-June1961. For his contribution to this group show, Brecht placed three

(white, black and yellow) chairs in different locations in the exhibi-tion; the white chair, for example, stood next to the gallery entrance.Though the score was handed out to visitors, many of them failed tonotice the chairs and casually sat on them. For Brecht, noticing thechairs constituted ‘occurrences’ that were in themselves perform-ances of theThree ChairE vents.Though Brecht's ‘assembled notes’on the event would not have beenas widely read as Kaprow's publications (or those by Alloway,Burnham, or Lippard), I would like to argue that they offer a crucialframework to understand one specific type of ‘non-compact’artworkin the 1960s: a ‘borderline’ art that balances on the precarious linebetween art and everyday life. This line also lay at the heart of Kaprow's practice, whose move from happenings to ‘activities’ in themid-1960s could be read as a shift towards the kind of event scorethat Brecht had been developing since the beginning of the decade.When Kaprow spoke (in a 1967 essay mentioned by Alloway) of the‘paradoxical position of being art-life or life-art’ occupied by his activ-ities, he seemed to be toeing the very ‘borderline’ described byBrecht[KAPROW1967: 87]. This is why ‘activities’ according to Kaproware ‘risky’: this ‘paradoxical position’ is precarious because the ‘hand-shake’ between participants and their ‘environment’ can easily belost [KAPROW1967: 88].

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

11/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

This ‘handshake’ is precisely what turns Kaprow's activities into a kindof system in the sense outlined by Burnham. Brecht seems to havebeen aware of systems theories as early as 1959, and his notes sug-gest that he was interested, like Burnham, in cybernetic models.3Brechtwas apparently preoccupied with the ‘points’ at which ‘random-ness intersects order, knowledge, control, open systems’, and believedthat these five ‘reference-frames’ could be imposed or ‘arranged’ oneveryday reality [BRECHT1960: 157]. The ‘event’ score may haveemerged as the ‘point’ in which all five reference frames intersect witheach other, and with reality, but Brecht abandoned this cybernetic

vocabulary in his final formulation of ‘borderline’ art. Brecht's interest in‘reference frames’seems to have shifted fairly quickly towards a moregeneral consideration of different ‘modes of apprehension’of reality (bethey myth, religion, art or science), and the point where there is ‘nograsping’of life, since everyday life exists without form, ‘beyond dimen-sions’.4 This is why ‘borderline’ art – an art which problematises ourvery mode of apprehension of, or ‘reference frames’ imposed on, reali-ty – is an ‘art verging on the non-existent; dissolving into otherdimensions, or becoming dimensionless, having no form’[BRECHT1961:74B-C]. Events are ‘extensible to the limits of form’ because theyinclude a temporal as well as spatial dimension, which makes them‘less localisable, less distinct’ than objects. In addition, they refuse tobe separated from everyday experiences as something ‘special’.5Brecht's crucial input in the discussion of dematerialised practices inthe 1960s was partly shaped by his interest in Zen. His belief in theeveryday as ‘nothing special’, in contrast with ‘special’ events suchas art, dance, theatre or music, was no doubt derived from Zen phi-losophy, with which Brecht was familiar thanks to popularisers suchas D.T. Suzuki and Allan Watts (whose books and lectures werehighly influential for Brecht), as well as cultural references as variedas theChineseBook of Changes(the I Chingfamously used by JohnCage to compose his scores) and Japanese haiku poetry.6 For exam-ple, Brecht cites theI Chingto highlight the fact that ‘nature createsall beings without erring […]. Therefore it attains what is right for all,without artifice or special intentions’[BRECHT1961: 9]. If nature offersus ‘things exactly themselves’ [BRECHT1960: 133], then the haiku

which, according to Watts, ‘sees things in their “suchness,” withoutcomments’, appeared as an ideal model for the event score [WATTS1957: 185].7 While the haiku is an ‘image of a moment in life’, howev-er, the event score is, according to Brecht, a ‘signal preparing one for

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

12/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 41

the moment itself’ – it exists in the present and the future, as well asthe past [BRECHT1961: 74-75A].8Brecht's perspective on ‘borderline’ art establishes a clear relationbetween the artwork's precarious existence ‘at the point of impercepti-bility’ and everyday reality itself: it is because life itself has no form thata ‘nothing-special’artwork that seeks to grasp it will inevitably teeter onthe point of ‘becoming dimensionless, having no form’. This uniqueinsight sheds new light on Alloway's theory of art and interface by shift-ing the focus away from the boundaries imposed by definitions of art, tointerrogating the reasonswhythese boundaries of art shifted, and

addressing the precise nature of their relation to the everyday.Significantly, Lippardherself became aware of such substantial distinc-tions, as she declared in a 1969 interview that certain conceptualartists remained ‘very much concerned with Art, with retaining a con-sistency, or coherency’, whereas others chose in contrast to ‘include’‘far more than’‘they exclude’, thereby adopting ‘an acceptive instead of a rejective approach’[LIPPARD1973: 7]. Even when an artist choosing thelatter approach decides to ‘use non-art, immaterial situations’, he or sheimposes ‘a closed instead of an open system’ that will work to assert ‘aformal or structural point of view’. In this way, Lippard succeeded inextending Alloway's opposition between the ‘solid’, ‘united, composed,stable’object on the one hand, and ‘diffuse’or ‘expanded’ art forms onthe other, beyond a polarity between conventional, autonomous art-work and ‘dematerialised’ practices. Even ‘non-compact’ forms, sheargued, can carry over certain artistic concerns with ‘compact’, coher-ent and consistent structures. Though Lippard's inventory inSix Years,like Alloway's list of ‘non-compact’forms, makes no distinction betweenthese different approaches, I would like to argue that it is central for ourunderstanding of dematerialisation at this time.If Lippardbriefly drew attention to the ‘degree of acceptance’ involvedin dematerialised conceptual practices, and Alloway spoke of the‘degree of compactness’ that constitutes a ‘minimum requirement of aesthetic identity’, Brecht's ‘borderline’ art exists precisely at theinterface between these two variable systems. The more it accepts‘non-art’ reality, the less compact and thus less legible an art formbecomes, leading us to wonder, with Brecht:

If art were not in form, it could be (life) instead of art.or: Can art not be in form and still be art?

BRECHT[1961: 74-75A]

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

13/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

Street Works

It was both the setting and the looseness of the format that allowedthe 1969-1970Street Worksevents to venture into the ambiguousterritory of borderline art. According to John Perreault, the poet andcritic who was the main spokesman for the events, a Street Workcould be ‘anything that takes place in the street or is placed in thestreet, calls attention to the street, is temporary, and is designated orcreated by an artist as a Street Work’[PERREAULT1969-70]. The defini-tion of the work was entirely contingent on the specific time and

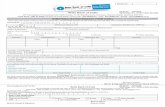

place designated by Perreault and his co-organisers. Apart from theannouncement (fig. 1), there was no systematic visual documenta-tion of the events; most of our knowledge derives from a supplementto issue six of the magazine0-9 edited by Vito Acconci andBernadette Mayer, who both participated in the firstStreet Works, aswell as Perreault's fragmentary reviews in theVillage Voice, alongwith the odd proposal, photograph, or press release.9 The formatvaried from oneStreet Workto another – variables included thenumber of invitations, as well as the designated area and time period.Street Works IV stands out as being the most carefully planned andadvertised because it was sponsored by the Architectural League inNew York; the street works that the limited number of artists createdfor the opening at the Architectural League, and for subsequentweeks, were all announced in advance. The lastStreet Works, whichwas namedWorld Works, differed from all past events in that itinvolved artists around the world performing Street Works at thesame time and subsequently sending their reports to the organisers.The organisers were the only ones to participate in all sixStreetWorks; some artists contributed repeatedly, others only once. Someworks are attributed to different artists by different sources, whileothers have remained anonymous. Few artists have kept records of their participation, and some fail entirely to mention their participa-tion inStreet Worksin their list of exhibitions or reviews.However marginal, theStreet Worksdid not occur in a void. They wereabove all a collaboration of artists and poets who were exploring dif-ferent formats for the presentation of their work. Perreault, Weiner

and Eduardo Costa (who would participate inStreet Works I-IV ) hadorganised in January 1969 the widely publicisedFashion E ventPoetry Show, for example, which had invited both visual artists andpoets to create innovative costumes to be modelled by their friends.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

14/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 43

Other poetry performances took place during this period in artist'slofts, clubs and bars, as well as galleries and museums. Meanwhile,Acconci and Mayer created0-9 as a magazine that would bringtogether poets and conceptual artists. Writing about the relationsbetween poets and conceptual artists in0-9, Lytle Shaw has traceda parallel between the dematerialisation of the artwork pursued bythe visual artists and a ‘materialisation of language’ among thepoets [SHAW2006: 156-157]. As Shawexplains, ‘The desire tomateri-alise’ language ‘was directed against an easy “consumption”’ of ‘poems as unmediated tokens of interiority’, in much the same way

as the artists sought to resist the consumption of artworks as com-modities. Taking poetry off the page was one of the strategiespursued by Acconci, Weiner, Mayer, and many of the other poets par-ticipating inStreet Works.A dialogue between poets and artists had occurred earlier withFluxus, whose precedent is not acknowledged in Perreault's writingsat the time, although several Fluxus artists, including BenjaminPatterson, Bici and Geoff Hendricks, did in fact participate in some of theStreetWorks. Indeed, Fluxus had staged some events in the sameneighbourhood asStreetWorksas early as 1964, and Mieko Shiomi'sSpatial Poems, started in 1965, are clear precursors of the 1970World Works. (In theSpatial Poems, Shiomi sent a score to differentfriends and acquaintances across the world and collected theirresponses, either by printing them together on the pages of a book,or by inscribing them on a map of the world, using tiny flags. Theorganisers ofWorld Worksmay also have wished to compile a publi-cation of the performance records that they received, but without asingle instruction or score like the one Shiomi sent around, theoverview would no doubt have lacked focus.)If Perreault failed to refer to Fluxus, he did point to contemporarymanifestations of art in the street, orchestrated by artists such asJames Lee Byarsand Yayoi Kusama. Byars contributed to bothStreetWorks Iand II, along with other artists such Acconci or Adrian Piper,who would also start using the street as a location for their practicearound that time, though for solo, sometimes invisible, perfor-mances different from the more spectacular street events set up by

Byars. Other artists such as Marjorie Strider or Rosemarie Castorocreated forStreet Worksspecific pieces that largely remain unlikeanything else they had done before and have done since. Castorocycled along the streets with a leaking tin of enamel paint at the back

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

15/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

of her bicycle forStreetWorks I(fig. 2) and unrolled a thick aluminiumscroll along the streets (forStreet Works III). (ForStreet Works II, shelaid out a line of aluminium tape to create ‘an atoll out of Manhattan’(fig. 3), a device she would subsequently use indoors.) InSix Years,Lippard – who had participated inStreetWorks Iherself – reproduceda summary of Strider's contributions to five of the artist's sixStreetWorks(fig. 4). Overall, Strider's approach as a painter – she wasalready known as a Pop artist by then – involved the simple use of painting frames: she hung them around the street (where many werestolen by passers-by) inStreet Works Iand II, inscribed the words

‘PICTURE FRAME’ on a banner inStreet Works III, and built a fifteen-foot frame that visitors walked through on their way into theArchitectural League for the opening ofStreet Works IV . ForStreetWorks V , she taped picture frames on the sidewalk for people to walkinto, and forStreetWorks VIorWorld Works, she asked passers-by tohold up a frame as she snapped their portraits with her camera.10Other participating artists inStreet Works, such as Athena Tacha orScott Burton, would go on to develop public art projects in citiesacross the United States, thus pursuing their desire to take art to thestreet, but in permanent rather than temporary forms. ThoughPerreault mentions ‘urban art’ in one of hisStreet Worksreports, itappears that Land Art – also known as Earth Works – would havebeen the most obvious point of comparison at the time. As heexplained, ‘Some artists making Street Works wish to call attentionto the city environment in much the same way as Earth Art brings thenatural environment to our attention’ [PERREAULT1969-1970].Retrospectively, he has mused that many Street Works artistsagreed with him that Earth Art was ‘elitist’ to the extent that ‘it stilldoes take a considerable amount of cash to visit Robert Smithson'sSpiral Jetty’ [PERREAULT2008].Though some art world friends and acquaintances did come to ‘huntdown’ the works, in particular at the official opening ofStreetWorks IV at the Architectural League, the main audience for theStreet Worksconsisted largely of other participating artists and random passers-by. Statements from the organisers stressed their desire to reach anaudience broader than the usual constituency of visitors to art

events and galleries. The new context, they claimed, gave greaterfreedom to the artists, while allowing them to witness their audi-ence's reactions immediately. Moreover, according to theStreetWorksorganisers, ‘The appearance of “works” at unexpected times

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

16/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 45

and unexpected places’ would inevitably lend the works a ‘quality of surprise’which would bring ‘the street environment into greater con-sciousness’.11 While Perreault's above-cited definition of a StreetWork depended on the figure of the artist, he nevertheless expressedthe paradoxical belief that ‘as soon as the man on the street is able toidentify a Street Work as a work of art, the Street Work ceases to existas a work of art’ [PERREAULT1969e: 16].Rather than giving an exhaustive account of eachStreet Worksinorder to bring these little-known events out of obscurity, I would liketo outline here a typology of forms and characteristics which will

shed light on their place in the discourses of dematerialised, expand-ed and borderline art that I have mapped out. A first type of StreetWork involved the simple of act of naming, framing or labelling every-day objects and places in the street. AtStreet Works I, in addition toStrider's painterly frames, Lippard circled in chalk any poet she met,and labels were affixed by both Weiner and Acconci – Weiner's labelswere blank, whereas Acconci pasted on buses signs that bore thetime when the labels had been attached, and the location of the busat that moment. This naming and labelling strategy intersects withanother, essential formal structure of many Street Works: their inher-ently ‘non-compact’ sprawl in space, whether through signs affixedon surrounding objects, or the numerous leaflets, poems, tissues,money, cards and maps randomly distributed to passers-by. If ban-ners and sandwich boards were used by poets and artists to createmobile works, Perreault'sT-Shirt Alphabetallowed him to use thismobility to disperse his poetry even further: for the opening ofStreetWorks IV , Perreault and twenty-five other participants each wore a T-shirt with a single letter from the alphabet. As Perreault announced,‘Any words that are spelled out’ – at the opening, and on the partici-pants' journey to and from the event – ‘will be accidental.’12Throughout theStreet Works, there emerges more particularly anattempt to disperse forms on the ground, as if to focus attention onpedestrian movements and trajectories. Thus, poems, messages anddrawings were scrawled and stencilled on pavements, and materialswere scattered on asphalt surfaces – in a Hansel and Gretel trail inthe case of Castoro's dripping paint (fig. 2) or Tacha's trickle of salt

as she went around Cleveland, Ohio (forWorld Works), or in changingheaps of powder (atStreet Works IV Mayer poured blue washingpowder, which turned to suds in the rain; Cristos Gianakos dumpedwhite flour on the road atStreet Works III(fig. 5), ‘creating a beautiful

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

17/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

nighttime piece’, Perreault noted, ‘as cars passed by [and] gentleclouds of white rose up’ [PERREAULT1969c: 17].) Silver stars weresprinkled on the pavement by Weiner atStreet Works V , while JohnGiorno was suspected to have strewn nails on the road atStreetWorks III.The nails on the street were a good pretext for the police to put anend toStreet Works IIIan hour and a half before it was supposed tofinish. Other police interventions duringStreetWorksdrew their ownboundaries between private and public space, and between harm-less artistic gesture and the subversion of the public order (or threat

to private property). For example, the police forbade poet Luis Wellsfrom surrounding an area with a dotted line inStreet Works II, whilethey ripped down a tape, bearing one of Weiner's poems written inInternational Code of Signals, that the artist had used to try and tieup a city block duringStreet Works III. Surprisingly, they did not stopGiorno and his friends from distributing his sexually explicitKamaSutra Poemat Street Works II, although they had questioned theartist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt when he was handing out ‘MissMadison Avenue Teenage Queen of Arts Contest’ questionnaires atStreet Works I.Other artists included inStreet Workssought to disorient viewers byeffecting a number of dislocations ordétournements . InStreet WorksII, Rosemary Mayer (Bernadette's sister) used labels to change allthe numbers of the buildings in one of the streets, while StevenKaltenbach went to great lengths to transplant the litter out of hisneighbourhood of residence, by taking Polaroid photographs of thelitter in its original location before placing it in paper bags and carry-ing it to the location designated forStreet Works I. Two poetsconducted a tour – one of them using a guide to London – duringStreet Works III; Abraham Lubelski invited viewers at the same eventto visit the Royal Waste Removal Corporation, where Perreaultadmired ‘piles of beautiful, anti-formal, condensed mess’ [PERREAULT1969c: 17]. (In the earlierStreet Works I, Lubelski had added a stripof lawn on the sidewalk in front of a bank (fig. 3).) Puns appealed topoets as a simple tool to introduce randomness in the framework of the street. While Charles Haseloff felt compelled to ‘sweep Broome

street’ forStreet Works III, Hannah Weiner organised a meeting withthe other Hannah Weiner she had found in the New York phonebook,and set up, under the titleWeiner's Wieners, a cart giving away hot-dogs at the opening ofStreet Works IV .

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

18/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 47

All such formal devices certainly succeeded in defining Street Worksas ‘non-compact’ works, comparable, for example, to the ‘permissiveconfigurations’ that Alloway perceived in Robert Morris's soft sculp-tures and Barry Le Va's scattered ‘distributions’, or bringing to mindSmithson's interest in the ‘overlap of systems’ as he re-titled sites of an abandoned industrial landscape in Jersey for his grand tour of theMonuments of Passaic[ALLOWAY1969: 208; ALLOWAY1973: 230]. Asmuch as the non-compact formsof the Street Works, however, it wastheircontent or subject-matter that aligned them with a borderline arthovering ‘at the point of imperceptibility’. For the organisers, Street

Works were aimed at ‘the man in the street’ –Street Works Iwas‘intended for those who were in the area, shopping, strolling, anddoing various Saturday midtown things during the natural course of their lives’; at the location ofStreet Works V , ‘[t]here were bums slug-ging down cheap wine, ladies lugging Christmas trees, and otherladies leaning in doorways’ [PERREAULT1969a: 17]. So when ScottBurton's contribution toStreet Works IIinvolved him walking aroundin drag pretending to be a lady running her Saturday afternoonerrands, or when Weiner leaned in a doorway herself duringStreetWorks V , they were literally mimicking the activities of the men andwomen in the street to whom the Street Works were addressed. WhileWeiner concluded that pretending to be a prostitute was ‘not a nicefeeling at all’, many marvelled at Burton's disguise – his was the‘most invisible and most sensational work’ atStreet Works II,remarked Perreault [WEINER2007: 25; PERREAULT1969b: 14]. AtStreetWorks II, Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt and his assistant panhandled thedesignated area and earned $6.33, whereas Eduardo Costapreferredto undertake ‘useful work’ instead of loafing around, by replacingmissing signs and trying to repaint a subway station (forStreet WorksI), or translating Spanish signs in English and vice-versa (forStreetWorks II). Meanwhile, Perreault'sStreet Music, performed atStreetWorks IandII(fig. 1), merged with the ambient noises of the street ashe went about calling one phone booth from another and letting thephones ring three time before hanging up (forStreet Music III, thedialling phones were left off the hook so that the ringing would be con-tinuous). ‘The work was invisible and for the most part inaudible’,

Perreault observed aboutStreet Music Iand II[PERREAULT1969d].‘Hardly anyone noticed’Street Music IIIeither [PERREAULT1969b: 14].If some of the Street Works involved some social gatherings –whether it was Lil Picard inviting participants for a beer atStreet

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

19/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

Works V or Les Levine celebrating his birthday at the opening of Street Works IV – the prototypical ‘man in the street’is a lonely figure,of which the flâneur is the best-known, modern trope. The mostfamous work performed in theStreet Worksseries is probablyAcconci'sFollowing Piece, which has been discussed in relation tothe Baudelairien and Surrealist flâneurs.13 Following Piece, whichinvolved the artist choosing a person randomly every day, for amonth, and following him until ‘he enters a private place’, was per-formed duringStreet Works IV , after Acconcihad already contributedeight Street Works – atStreet Works I, II, III, and at the opening of

Street Works IV [ACCONCI1969]. The ‘situations using streets’ thatAcconci set up duringStreet Works Iinvolved, in addition to pastinglabels on buses (which I mentioned earlier), the artist walking con-tinuously along the sides of a single sidewalk for three hours, duringwhich someone would perhaps wonder ‘whether or not he hadalready seen’ him (fig. 6). ForStreet Works II, he stood on a corner,singled out a passer-by, and ran to the other corner to get therebefore that person arrived at that point; he would then note the timeof his arrival. These two works resonate with the Fluxus artistPatterson's contribution toStreet Works I, which involved him ‘cross-ing the street at an intersection back and forth in each direction forfifteen minutes each way’ – a performance, in fact, of his 1962 scoreTraffic Lights: A Very Lawful Dancewhich, as Dick Higgins had previ-ously noted, highlighted ‘the non-memorable, disappearing aspect of his work’ [HIGGINS1964:59]. Acconci's participation in the opening of Street Works IV was more static, as he stood watching the trafficnearby for two hours, thinking, among other things, of ‘someone elsestanding in similar position elsewhere’. Acconci had further probedthe dynamics of hisStreet Workscontributions by exploring two ‘sit-uations’ during August 1969: in both he ‘picked out (mentally)’ apasser-by in the street, but in one of the situations he followed themand then slowed down, while in the other he stood still at one cornerand watched them turn the other corner. In both cases the work con-tinues ‘until the person chosen is out of view’.14If Patterson, like many Fluxus artists, came from a musical back-ground (he was a professional double-bass player), Acconci's

‘situations’ created during and around the time of theStreet Workswere still closely related to his poetry, as his records for the workstestify. For each work, Acconci lists, defines and riffs on a number of related words and expressions – like ‘point’ or information inStreet

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

20/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 49

Works I(fig. 6), ‘corner’, ‘on the street’, ‘drift’, or ‘going the distance’(for hisSituation Using Streets, Walking, RunninginStreet Works II),or ‘to stand one's ground’ and ‘right up your street’ (for each of histwo contributions toStreet Work IV ). The diaries that he kept of theFollowing Piece, and the pages from this diary that he subsequentlysent out to various friends and art world professionals, certainlyhighlighted the narrative drive at the heart of the work. WhatAcconci'sStreet Worksdemonstrate above all, however, is a shiftfrom literature to a preoccupation with sight and action, as ‘glancing’in the first work turns to ‘watching’ and ‘following’ in the later ones.

Moreover, many of hisStreet Worksfocus on his ‘invisible’ interac-tions with passers-by, with whom he identifies yet simultaneouslytries to compete, thus objectifying them – in what Tom McDonoughhas described as a ‘libidinal tangle in which pursuer and pursued[have] lost their clear polarities’ [MCDONOUGH2002: 107]. In this way,Acconci'sFollowing Piecerevealed the central dynamic betweenpublic and private that lies at the heart of the street environment,which shaped and was shaped byStreet Works. By putting out theirwork in the public arena of the street, the artists involved inStreetWorksseemed to have given up all claims to ‘private intention’.15 Yet,at the same time, many Street Works were so private that in manycases they remained a secret that could only be perceived after thefact, through documentation. (Kaltenbach went so far as to con-tribute an undisclosed ‘secret piece’ toStreetWorks IV .) This polarity,I would argue, is inherent to the very nature of the everyday itself,which is everywhere to be seen, yet remains illegible.

AnE veryday Vocabulary

Maurice Blanchot's essay on the everyday, ‘La parole quotidienne’,was initially published in 1962 under the title ‘L'homme de la rue’ –the man in the street. For Blanchot, the everyday is ‘imperceptible’or‘unseen’ (inaperçu) because it is always there and can never beenclosed ‘in a panoramic vision’ [BLANCHOT1962/1969: 357-358].16Similarly, the man in the street ‘has always seen everything, but is a

witness of nothing… not out of cowardice, but rather out of light-ness, because he is never really there’ [BLANCHOT1962/1969:362-363]. So when a Street Work resists being ‘identified as art’, andthereby ‘neatly filed way’, as Perreault wished, and the artist thus

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

21/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

remains an anonymous ‘man on the street’, they come closer tobeing as ‘imperceptible’ as the everyday [PERREAULT1969e: 16]. Thisis where the ‘power of dissolution’of the everyday lies: its ‘corrosive’powers, as Blanchot called them, erode the very notion of the sub- ject, and by extension, it will dissolve the fixed contours of art[BLANCHOT1962/69: 365].Some of the characteristics of ‘borderline’ art according to Brechtareits ‘gentleness, frugality, reticence’ [BRECHT1961: 74B-C]. All theworks inStreet Works I, explained Perreault, were similarly ‘soft,gentle, and practically invisible. Nothing was damaged’ [PERREAULT

1969a: 17]. Indeed, Perreault was careful to note that the nailsstrewn on the road inStreet Works IIIwere untypical of the manifes-tation as a whole, and the poster-instructions forWorld Worksexplicitly specified that ‘a street work does not harm any person orthing.’ I believe that this gentleness intersects with one of the keyfeatures that Burnham singled out in Kaprow's mid-1960s happen-ings or activities: their reversibility. As Burnhamnoted, ‘Alterations inthe environment may be “erased” after the Happening, or as a part of the Happening’s conclusion’ [BURNHAM1968: 35]. Similarly, StreetWorks left few material traces behind, beyond lines of paint or chalkthat would eventually fade and disappear.The ‘frugality’of the Street Works – like that of Brecht's scores as wellas Kaprow's contemporary scripts – lie in their economy: most couldbe summarised in a few words. As to their ‘reticence’ – also noted byAllowayapropos Brecht's events – they offer an alternative to the‘aloofness’ discussed by Lippard and Chandler [ALLOWAY1975a: 196;LIPPARDand CHANDLER1968: 257 and 271]. While ‘reserve’ is a syn-onym for both terms, aloofness suggests a superiority and coldnessthat are foreign to reticence, which is more closely related to shy-ness and discretion. For Lippard and Chandler, the aloofness of dematerialised works is related to their ‘self-containment’ and their‘hermeticism’, ‘manifested as enclosure or monotonality and nearinvisibility, as an incommunicative blank façade or as an excessiveduration’. In contrast, the ‘near invisibility’ of the Street Works andborderline art in general does not derive from their ‘self-containment’– gentle and frugal, they seek to open up and blend in with their sur-

roundings, offering transparent windows onto the world (likeStrider's frames), rather than ‘incommunicative blank façades’.For John Gruen, theStreetWorkscould be related ‘to the current phe-nomenon of anti-illusionistic art that wishes to convey a sense of the

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

22/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 51

fragmentary, the tentative, the insubstantial’[GRUEN1969]. The timid-ity of the ‘tentative’ certainly relates to the shyness of the ‘reticent’,but it is with the ‘insubstantial’ that I would like to conclude. For theinsubstantial, firstly, could well provide another, more useful termthan the ‘immaterial’ or the ‘dematerialisation’at stake in this essay.Secondly, the insubstantial brings to mind theinsignifiant(‘insignif-icant’) that characterises the everyday according to Blanchot. The‘insignificant’, for Blanchot, ‘is without truth, without reality, withoutsecret, but it is perhaps also the place where all signification is possi-ble’ [BLANCHOT1962/69: 357]. This parallel between insignificant

practices and the everydayinsignifiantcan help us to address, inconclusion, the politics of the ‘borderline’ brand of conceptual artembodied in Brecht's scores, Kaprow's activities, Street Works, andother ‘acceptive’ forms of conceptual art.In the same way that Lippard and Chandler insisted that demateri-alised practices could not be bought and sold, Perreaultacknowledgedthat a political dimension could be read in the simple fact that theStreet Work ‘exists outside the gallery-museum economic structure’[PERREAULT1969-1970]. Yet, as Lippard had already realised by thetimeSix Yearswas published, this political project was quickly provedunsuccessful, because such projects did end up being bought andsold [LIPPARD1973: 263-264]. Indeed, as Thierry Davila demonstratesin his ‘brief’ but masterly ‘history of imperceptibility from MarcelDuchamp to today’, 1969 can be called ‘the year of invisibility’ in theUnited States precisely because it was ‘a particularly rich moment forpublic manifestations of an invisible art through clearly identifiableexhibition strategies’ that simultaneously relied on and subverted thecommodification of artworks as well as the very mechanisms of theart world [DAVILA2010: 147].17According to Alistair Rider, the exhibition curated by Lippard at thePaula Cooper Gallery in May and June of 1969 constitutes a clearexample of the failure of dematerialised art to escape from the com-mercial art world. Lippard's exhibition included, in fact, the same kindof aluminium tape that Castoro had unrolled to create an ‘atoll out of Manhattan’a month earlier inStreet Works II: this time, it threatenedto visually ‘crack’open the space of the gallery along the floor and the

walls. Transposed from the street to the gallery, Castoro'sCrackingcan be read by Rider as epitomising the unfulfilled ‘anti-establish-ment longings of the moment’ [RIDER2008: 149]. According to Rider,an artist such as Smithsonrefused to give in to such evident forms of

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

23/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

‘wish fulfilment’ – by acknowledging the existence of boundariessuch as the gallery walls and working with them.The differences between Castoro'sCrackingand her attempt to‘make an atoll out of Manhattan’ atStreet Works IIclearly highlightthe importance of location for borderline works. Rather than con-demning them for their escapism or naivety, however, I would arguethat ‘borderline’ practices such as those of Brecht and Kaprow, or‘acceptive’conceptual practices like the Street Works, did not seek toovercome the boundaries between art and non-art by working out-side the gallery, but rather probed these boundaries in search of

‘social energies not yet recognised as art’, as Lippard put it in a ret-rospective account [LIPPARD1993: XXII]. While the idea of ‘limits’central to Smithson's thinking is contained in the very definition of ‘borderline’ art, it is the energy that can be sparked by the frictionoccurring at this boundary that is central to the practices that I havediscussed. Indeed, the idea of ‘energy’ is implied in Burnham's read-ing of dematerialised practices as systems, and Alloway's interest inthe interfaces of a dynamic, ‘expanding’ work of art. Crucially, asLippard suggested:

The process of discovering the boundaries didn't stop with Conceptual art: These ener-gies are still out there, waiting for artists to plug into them, potential fuel for theexpansion of what ‘art’ can mean.

LIPPARD[1993: XXII]

Such a promise, I believe, can certainly be retrieved in the spirit of Street Works, and in the general insignificance of borderline art as‘the place where all signification is possible’.

1 Research for this essay was made possible by a Terra Foundation for American ArtPostdoctoral Fellowship at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I would also liketo thank the artists and poets who kindly responded to my queries and requestsfor images: Vito Acconci, Rosemarie Castoro, Cristos Gianakos, Abraham Lubelski,John Perreault, MarjorieStrider and Athena Tacha.2 Alloway reviewed both Kaprow's 1966 Assemblage,E nvironments andHappeningsand his 1969Days Off, A Calendar of Happenings, which documenteda number of happenings performed in 1969. The two reviews – originally publishedin Arts MagazineXLI/3 (December 1966-January 1967) andThe Nation(20

October 1969) – are both included in ‘Allan Kaprow: Two Views’, in ALLOWAY[1975a].Burnham refers to Allan Kaprow's ‘The Happenings Are Dead: Long Live theHappenings!’, Artforum(March 1966), in BURNHAM[1968: 35]. The scores/posterforSix Ordinary Happeningscan be found in Allan Kaprow: Art as Life[2007: 207].

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

24/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 53

3 Brecht mentions ‘systems’ in hisNotebook II[1958-1959: 65]. InNotebook V [1960: 157], he refers to Stanford BEER's Cybernetics and Management[1959].4 Brecht writes about ‘modes of apprehension’ for a ‘Statement for JamesGoldsworthy’, written in June 1960. SeeNotebook V [1960: 151]. The term ‘beyonddimensions’ appears in ‘Events (assembled notes)’, a first version for ‘Events:Scores and Other Occurrences’ (written sometime between 20 April-19 May 1961)inNotebook VI, [1961: 74-75C].5 ‘Objects/Events/Situations’, notes for an unpublished article, inNotebook V [1960: 239].6 For an excellent study of the influence of East Asian culture and philosophy onBrecht's ‘borderline art’, see KNAPSTEIN[1999].7

Brechtdoes not include this quotation by Watts in his text, but he read Watts'writings and attended his lecture series on ‘Religion and Language’ at the NewSchool for Social Research in 1961.8 Though not referenced, the quotation from Wattsmay have been drawn from aLifearticle about Watts, ‘Eager Exponent of Zen’[ANONYMOUS1961: 88A]. In theLifearticle, it reads, ‘The haiku is a concrete image of a moment in life’.9 Most of the material can be found in PERREAULTandCOLLISCHAN[2008].10The summary inSix Years[LIPPARD1973: 91] refers to Strider's contributions toStreet Works I-V . Information aboutWorld Workscan be found in the Marjorie Strider

Papers.11 John Perreault, Marjorie Striderand Hannah Weiner, ‘Street Works – a Statementby the Coordinators’, rep. in PERREAULTand COLLISCHAN[2008].12 John Perreault, ‘Artist's Comments’, in‘Street Works IV’ , programme of events,rep. in PERREAULTand COLLISCHAN[2008].13 See, for example, Tom MCDONOUGH, ‘The Crimes of the Flâneur’ [2002], andMargaretIVERSEN, ‘Following Pieces: On Performative Photography’ [2007]. For ageneral discussion of walking in surrealism and contemporary art, see AnnaDEZEUZE, ‘As Long as I'm Walking…’, in DEZEUZE[2009].14

See Vito Acconci, ‘Streets, Walking, Watching, Aug 1969’, in ACCONCI[2006].15 Burnhampraised Donald Judd's criticism because it ‘cleared the air of muchcriticism centred around meaning and private intention’ [BURNHAM1968: 32].16 My translation.17 My translation.

ANONYMOUS[1961]. ‘Eager Exponent of Zen’,Life, April 21, pp.88A-93.

ACCONCI, Vito [1969]. [untitled text] inStreet Works, supplement to themagazine0-9, no6, July, n.p.ACCONCI, Vito (et al.) [2006].Diary of a Body. Milan, New York: Charta. Allan Kaprow: Art as Life[2007]. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

25/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

ALLOWAY, Lawrence [1969]. ‘The Expanding and Disappearing Work of Art’, Auction, III/2, October, rep. inTopics in American Art since 1945. New York:Norton, 1975, pp.207-212.ALLOWAY, Lawrence [1973]. ‘Robert Smithson's Development’, Artforum , XII3, November, rep. inTopics in American Art since 1945. New York: Norton,1975, pp.221-236.ALLOWAY, Lawrence [1975a]. ‘Allan Kaprow: Two Views’, inTopics in American Art since 1945. New York: Norton, pp.195-200.ALLOWAY, Lawrence [1975b].Topics in American Art since 1945. New York:Norton.BEER, Stanford [1959].Cybernetics and Management. New York: Wiley.BLANCHOT, Maurice [1969].L'entretien infini. Paris: Gallimard.BLANCHOT, Maurice [1962/1969]. ‘L'homme de la rue’,Nouvelle revue française, 114, June, pp.1070-1081, rep. as ‘La parole quotidienne’, inBLANCHOT[1969: 355-66].BRECHT, George [1958-1959].Notebook II ,October 1958-April 1959, ed.Dieter Daniels. Köln: Walther König, 1991.BRECHT, George [1960].Notebook V, March-November 1960, ed. DieterDaniels. Köln: Walther König, 1998.BRECHT, George [1961].Notebook VI, March-June 1961, ed. Dieter Daniels.Köln: Walther König, 2005.BRECHT, George [1964]. ‘Events: Scores and Other Occurrences’(editorial),12/28/61, incc V TRE No.1 FLUXUS, January, p.2.BURNHAM, Jack [1968]. ‘Systems Esthetics’, Artforum, September, pp.30-35.GRUEN, John [1969]. ‘Street Works, Theatre Works “Enigmatic”’,Vogue,August 1, rep. in PERREAULTand COLLISCHAN[2008].DAVILA, Thierry [2010].De L'Inframince: Brève histoire de l'imperceptible deMarcel Duchamp à nos jours. Paris: Éditions du regard.

DELL, Simon (ed.) [2008].On Location: Siting Robert Smithson and hisContemporaries. London: Black Dog.DEZEUZE, Anna (et al.) [2009].Subversive Spaces: Surrealism andContemporary Art. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery.DEZEUZE, Anna [2009]. ‘As Long as I'm Walking…’, in DEZEUZE[2009: 64-80].ELKINS, James (ed.) [2007].Photography Theory. London, New York:Routledge.HIGGINS, Dick [1964]. Jefferson's Birthday. New York, Nice, Köln: Something

Else Press.IVERSEN, Margaret [2007]. ‘Following Pieces: On Performative Photography’,in ELKINS[2007: 91-108].

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

26/36

DE M A T E RI A L I S A T IONS 55

KANE, Daniel (ed.) [2006].Don'tE ver Get Famous:E ssays on New YorkWriting after the New York School. London, Champaign, Dublin: DalkeyArchive Press.KAPROW, Allan [1966]. Assemblage,E nvironments & Happenings. NewYork: Abrams.KAPROW, Allan [1967]. ‘Pinpointing Happenings’, Art News66, rep. inE ssays on the Blurring of Art and Life , ed. Jeff Kelley. Berkeley, LosAngeles, New York: University of California Press, 1993, pp.84-89.KNAPSTEIN, Gabriele [1999].George Brecht:E vents – über dieE vent-Partituren von George Brecht aus den Jarhren 1959-63. Berlin: WiensVerlag.

LIPPARD, Lucy and CHANDLER, John [1968]. ‘The Dematerialization of Art’, ArtInternational, 12:2, February, rep. in LIPPARD[1971: 255-276].LIPPARD, Lucy [1971].Changing:E ssays in Art Criticism. New York: Dutton.LIPPARD, Lucy [1973].Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object from1966 to 1972 . New ed., Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1997.LIPPARD, Lucy [1993]. ‘Escape Attempts’, in LIPPARD[1973: VII-XII].MCDONOUGH, Tom [2002]. ‘The Crimes of the Flâneur’,October102, Autumn,pp.101-122.PERREAULT, John [1969a]. ‘Art on the Street’,Village Voice, March 27, pp.17-18.PERREAULT, John [1969b]. ‘Free Art’,Village Voice, May 1, pp.14-15.PERREAULT, John [1969c]. [review ofStreet Works III] [untitled extract froman article],Village Voice, June 5, p.17.PERREAULT, John [1969d]. ‘Street Music’,Street Works, supplement to themagazine0-9, no6, July, n.p.PERREAULT, John [1969e]. ‘Taking to the Street’,Village Voice, October 16,pp.15-16.

PERREAULT, John [1969f]. [review ofStreet Works V ] [untitled extract froman undated article],Village Voice, [ca. December 1969-January 1970].Unpaginated press cutting from the Marjorie Strider Papers, consulted atSpecific Object, New York.PERREAULT, John [1969-1970]. ‘Street Works’, Arts, December 1969-January1970. Unpaginated press cutting from the Marjorie Strider Papers.PERREAULT, John [2008]. ‘Street Works in Colorado’, Artopia: John Perreault's Art Diary, posted 6 October 2008 at:http://www.artsjournal.com/artopia/2008/10/street_works_in colorado_libes.html (accessed 16 August 2011).PERREAULT, John and COLLISCHAN, Judy (eds) [2008].In Plain Sight: StreetWorks and Performances: 1968-1971. Lakewood, CO: The Lab at Belmar.RIDER, Alistair [2008]. ‘Arts of Isolation, Arts of Coalition’, in DELL[2008: 132-149].

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

27/36

O B J E C T S I N P R O G R E S S

SHAW, Lytle [2006]. ‘Faulting Description: Clark Coolidge, Bernadette Mayerand the Site of Scientific Authority’, in KANE[2006: 151-172].SMITHSON, Robert [1969]. ‘Fragments of an Interview with Patricia Norvell’,June 20, cited in LIPPARD[1973: 87-90].WATTS, Alan W. [1957].The Way of Zen. London: Thames and Hudson.WEINER, Hannah [2007]. ‘Street Works I, II, III, IV and V’, inOpen House, ed.Patrick F. Durgin. Berkeley: Small Press Distribution, p.25.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

28/36

Fig. 1. Poster forStreet Works I, 15 March 1969, with map of John Perreault'sStreet Music I, asreproduced in0-9, supplement to no6, July 1969, n.p.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

29/36

Fig. 2. Rosemarie Castoro, Untitled contribution toStreet Works I, as reproduced in0-9, supplement tono6, July 1969, n.p.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

30/36

Fig. 3. View ofStreet Works II, 18 April 1969: metal tape from Rosemarie Castoro,How to Make An Atollout of Manhattan Islandunrolled by the artist on top of the strip of grass placed by Abraham Lubelski infront of the First National City Bank on 13th Street. Photo: Rosemarie Castoro.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

31/36

Fig. 4. Marjorie Strider,Street Work, 1969. Photograph and summary reproduced in Lucy Lippard,SixYears: the Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, London, Studio Vista, p.91.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

32/36

Fig. 5. Cristos Gianakos, untitled contribution toStreet Works III, 25 May 1969.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

33/36

Fig. 6a. Vito Acconci, A Situation Using Streets, Walking, Glancing, contribution toStreet Works I,15 March 1969: Description and notes.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

34/36

Fig. 6b. Vito Acconci, A Situation Using Streets, Walking, Glancing, contribution toStreet Works I,15 March 1969: Two photographs.

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

35/36

-

8/9/2019 Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, Dematerialisation

36/36