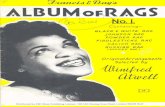

An Egyptian Source for Gen 1 - Atwell

description

Transcript of An Egyptian Source for Gen 1 - Atwell

-

AN E G Y P T I A N SOURCE FOR G E N E S I S W I I H I \ ancient Near Eastern thought the moment of creation was deemed to connect immediately to the existing order The primeval ordering of the world, however it was conceived, was therefore of unique philosophical and theological significance It conferred upon contemporary norms a legitimacy and permanence, beyond their true validity, which guaranteed them absolute status The priestly account of creation in Genesis 2 4a in a similar way confers upon Israel and her cultic institutions a legitimacy and validity within the given orders of creation In so doing it reveals one of the most distinctive Hebrew epic traditions as seamless with the prevailing cultural norms of the ancient world

It is evident that Genesis 1 1 2 4a draws upon the analogy of two different modes of creation in presenting its account There is the effortless word of God which orders the world into being in an instant This is then duplicated by a further account which speaks of the divine activity in a more earthy and basic way, that is, in terms of craftsmanship and manual labour seemingly more in keeping with the creation account of the Yahwist (J) in Genesis 2 3 The verbs used for this activity are 'to separate' (73, 1 4, 7) and 'to make' (, 7, 16) This latter also occurs in the opening line of the J narrative (Genesis 2 4b) and again with reference to the garments Yahweh made for his erring creatures (121) Another verb which seems to correspond in meaning with the simple word 'make', yet is restricted in priestly tradition (P) to the divine activity and is usually translated as 'create', is 3 It is worth noting that not only does the divine word have

1 The outstanding features of are that it is only used with God as subject

and never has the accusative of the material from which things are constructed It is obviously significant in the places where it is used in the Genesis 1 narrative That is in 1 1 at the very beginning in the formation of the great sea monsters (v 21) in the making of humankind (v 27) and again at the end (2 ,) Yet corresponds in manv wavs with the work account of creation J Morgenstern The Sources of the Creation Story Genesis 1 1 2 4a AjfSL Vol XXXVI no ^ (1920) pp 160. 212 placed it in his sabbath tradition Clearly in Genesis 2 } it is complementary to and not in opposition to the idea of making (57) Whereas in 2 Isaiah is applied to God s actions in the present for its use is restricted to describing God s creative action at the beginning It has a deliberate and considered significance when it occurs in but this falls short of creatio ex nihilo It is best understood in the context of the alternative verbs separate and make

Oxford University Press 2000 [Journal of Theological Studies NS Vol 51 Pt 2 October 2000]

I

-

442 JAMES h A r W E I I a foundational significance for the whole of priestly theology, but so also does the concept of separation Both tradit ions of creation by word and by work are therefore integral to the whole priestly scheme

T h e question arises do we have here two distinct traditions about creation with their own ' tradition history' which have been c o m b i n e d ? F Schwally in 1906 argued that the two types of creation in Genesis 1 are contradictory and therefore must have separate tradit ion histories T h i s suggestion was taken up and thoroughly examined by J Morgens tern H e gave priority to what he called the 'divine fiat' version of the creation narrative, over against the manufactur ing version which he called the 'sabbath ' version T h e 'divine fiat' narrative he took to consist of eight divine c o m m a n d s which form the basis of the Genesis narrative T h e s e , he envisaged, were cast in a pure form with textbook evenness T h i s material, he thought, had been supplemented by rather rugged secondary material which, unlike Schwally, he did not reckon had ever been a tradit ion of its own T h e intention was to popularize the rather scholastic text T h i s secondary material he labelled ' sabbath ' as he supposed the divine rest to relate to the exhausting procedure of the more physical labours T h e scheme of a week he connected with this supplementary material,

The priestly creation account represents a charter that stands over all sub sequent sacred history That account is not simply an isolated few verses that happens to preface the priestly narrative Rather it is securely bonded to all that follows The picture of the creator in the opening chapter of Genesis is summarized by the psalmist

By the word of the Lord were the heavens made And all the host of them by the breath of his mouth (Ps ,> 6) But that same picture holds good for subsequent history also God speaks and it comes to pass Whether it is the instruction to Abraham to circumcise him that is born in thy house (Genesis 17 1 }) which is deliberately and carefully fulfilled a few verses later (v 23) or whether it is the instruction to Moses in the detail of the setting up of the tabernacle (Exodus 40 1 ff ) which concludes hus did Moses according to all that the Lord commanded him so did he (Fxodus 40 16) the word of God as a matter of central priestly theology never returns to him unfulfilled

Things need to be regulated ordered put in their place Not least is this true of the cult which distinguishes Israel from the nations Within the cult Israel must be separated from her uncleanness (Leviticus is ^1 ff ) Aaron and his sons must be set apart from the children of Israel (Leviticus 22 2) and the Lvites must be separated (7"*73) from among the children of Israel (Numbers S 14) The reader is face to face in the subsequent narrative with the selfsame concept of separation that permeates the first chapter of Genesis It is part of the overture effect of Genesis 11 2 4a in relation to the whole priestly work noted by C Westermann

Schwally Die bibhsehen Schopfungsberichte ARW 9 (1906) pp iS9 7S J Morgenstern op cit

-

I G Y P l IAN S O U R C E I OR G E N E S I S 443 and also the motif of G o d declaring his work good as it envisages the possibility of failure

M L a m b e r t 6 reversed Morgens tern ' s assumptions as to which of the two accounts should be considered the prior, and which supplementary T h e matter was taken u p again by G von Rad in his at tempt to identify two literary strands t h r o u g h o u t the narrative 7 H e related his two strands to the two separate creation accounts, 'action account ' A and ' c o m m a n d account ' Von Rad ' s at tempt marks the end of any real hope that literary criticism might yield up a solution to the problem of sources in Genesis In his commentary von Rad himself makes only passing reference to this endeavour

W S c h m i d t 8 has turned to ' tradit ion history' for a way out of the impasse H e believes the failure of literary criticism makes it clear that there are not two distinct tradit ions about creation with their own prehistory T h e r e is one single line of development However he does conclude that the account of creation by action must be p r i m a r } , and that one can identify what seem to be the oldest elements in the tradition But he would still stress that the 'priestly m i n d ' is evident not simply in the c o m m a n d account with the oldest elements, as it were, surgically removed It is also there in the way the priestly t radents have over the generations selected, developed and shaped the old material Let us take as our starting point for investigation those elements which Schmidt identifies as at the source of a long period of priestly transmission

[i 2] And the earth was waste and void, and there was darkness over the great deep And the spirit of God hovered over the waters [4] And God separated the light from the darkness [7] God made the firmament and separated the waters beneath the firmament from the waters above the firmament [9] (according to the Greek translation) And the waters under heaven gathered themsehes into one meeting-place, and the mainland became visible [12] The earth brought forth green herbs, which yielded seed and trees which yielded fruit with seeds [16] God made the two great lights, the greater to rule by day, and the lesser to rule by night, and the stars, and God placed them in the firmament of heaven

( M Lambert A Study of the I irst Chapter of Genesis HUCA 1 (1924)

PP 12 7 G \ on Rad Die Priesterschrift im Hexateuch BWAN I 6s Stuttgart (19^4)

8 W H Schmidt Die Schpfungsgeschichte der Priesterschrift Neukirchen

(1967)

-

444 JAMES E A T W h L L [21] And God created the great sea animals, and the whole swarm of living creatures, with which the waters swarm and all winged creatures [25] And God made the wild animals the cattle and all of the creeping things of the earth [26-27] Then God said Let us make men in our image, so they will resemble us, to rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of heaven, the cattle, and all the wild animals on earth, and every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth And God created man in his image, in the image of God he created him [2 2] And God rested (?) 9

We can usefully ask two questions of the text in this form These two questions are

1 Where did the original cosmology come from? and 2 H o w does the pat terning of seven imposed upon the acts of

creation relate to the tradit ion history of Genesis 1? We may then consider the further question

3 What is the theological thrust of the narrative as it now stands?

I T H E O R I G I N A L C O S M O L O G Y

Where did the original cosmology come from?

/ A Comparison of the Priestly Creation Narrative with the Cosmology of Ancient Mesopotamia

T h e template which is normally held u p against the priestly cosmology for comparison is that of ancient Mesopotamian religion, and here particularly the work known as Enuma Ehsh W H Schmidt declares ' T h e tradit ion behind Genesis is closely related to the Babylonian epic of creation, the Enuma Ehsh ' 1 0

Enthus iasm for comparison with ancient Mesopotamia is fuelled partly by the evidence for comparisons in other areas of the

Ibid , I 6 I The translation is from Otzen et al (eds), Myths in the Old Testament London (1980), pp 29 f English translation from My ter Det gamie Testamente, Copenhagen (i97o2) Otzen himself supports Schmidt's endeavour 'Of course, such a division of the text should be accepted only with the greatest of reservations, but there can hardly be any doubt that most of the elements Schmidt has removed belong to the priestly redaction ' op cit , -jo Westermann is also positive 'Schmidt's study is an important step forward ' Genesis 1-11 A Commentary, London and Minneapolis (19S4), 8^ [translation from second German edition, Neukirchen-Vluyn (1976)]

W Schmidt, Introduction to the Old Testament (London, (1984), io2 English translation from Einfuhrung in das Alte Testament, (1979, 19822)

-

AN G Y P I I A N S O U R C E F O R G P N F S I S 4 4 5 primeval text, and partly by the m o m e n t u m established by H Gunkel Less emphasis has been accorded to comparison with Egyptian cosmology It is the conviction of this study that investigation there provides significant contours for comparison

Let us first investigate the more usual comparison What exactly are the resemblances between the priestly creation account and Mesopotamian parallels, particularly Enuma Ehsh^ A Heidel has discussed those elements of the priestly creation tradit ion that, in his judgement, show possible parallels with Enuma Elish H e concludes

In fact the divergences are much more far-reaching and significant than are the resemblances most of which are not any closer than we would expect to find in any two more or less complete creation versions But the identical sequence of events as far as the points of contact are concerned is indeed remarkable This can hardly be accidental

T h e points of contact and their order are presented by Heidel in table-form as follows (the n u m b e r i n g is our own)

Enuma Elish [i] Divine spirit and cosmic

matter are coexistent and coeternal

[2] Primaeval chaos, Ti'mat enveloped in darkness

[l] Light emanating from the gods

[4] T h e creation of the firma-ment

[5] T h e creation of dry land [6] T h e creation of the

luminaries [7] T h e creation of man [8] T h e gods rest and celeb-

rate

Genesis Divine spirit creates cosmic mat ter and exists indepen-dently of it (1 2) T h e earth a desolate waste, with darkness covering the deep (fhom) ( 1 2 ) Light created

T h e creation of the firmament

T h e creation of dry land T h e creation of the lumin-aries T h e creation of man God rests and sanctifies the seventh day

H Gunkel Schpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit (Gottingen 189s) asserts the Babylonian origin of the priestly creation narrative He allowed for dependence upon an intermediate Hebrew poetic recension of the Marduk myth which used the divine name Yahweh

12 \ Heidel The Babylonian Genesis (Chicago 1951 ) }o A Speiser

Genesis Anchor Bible (New York 1964) 9 accepts Heidel s conclusions as proven

A Heidel op cit 129

-

4 4 6 J A M P S L A T W F L L

T h e correspondence between the items designated [ i] is general rather than specific T h e idea that the gods developed from withm the raw material of creation is indeed standard in the ancient Near East Where the pre-creation condition was pictured as a watery abyss it was deemed to contain the origin of the gods as well as the origin of the natural world T h e two were reckoned as coexistent If Genesis 2 should be taken as a description of the primeval condit ion prior to creation then it may also be contrasted with Enuma Ehsh In the Enuma Ehsh t radit ion the hallmark of the primeval ocean is its torpor, the sleep of the primeval deities is eventually disturbed by the noise of the younger gods T h e r e is no real parallel to the dynamic 'Spirit of G o d ' as one element of the primeval condit ion distinct from its other qualities

In the same way [2] is also a general point relating to ancient Near Eastern m y t h in general rather than Enuma Ehsh in particular It is hard to think of any other way an account of creation in the ancient Near East could begin if it were not to commence with a description of the pre-existent formless condition T h i s is hardly remarkable W G Lamber t , who has reassessed the implications of correspondence between Genesis 1 and Enuma Ehsh, observes that a watery beginning is to be found elsewhere in cosmogonies of other peoples H e further dismisses the linguistic correspondence between the H e b r e w 01) fhm (masculine) without the article in Genesis 1 2 and the personified Tiamat (femmine) in the Akkadian epic as not significant ' T h e etvmolo-gical equivalence is of no consequence, since poetic allusions to cosmic battles in the use Yam and fhm indiscriminately ' Al though 'darkness ' is an explicit feature of Genesis 1 2, it is not so in Enuma Ehsh It has to be surmised by Heidel from the account of Berossus T h e r e is, therefore, little of real identity upon which to construct a specific relationship in item [2]

As regards [3], the claim to find a correspondence between light emanat ing from the gods, which is at most an incidental item to be deduced from the Babylonian narrative, and the crea-tion of light in Genesis 1 which is definitive for the whole narra-tive, is not convincing T h e r e is no real linkage of common purpose and direction

Heidel points to the creation of the firmament [4] and the crea-tion of dry land [5] for the next two items of correspondence T h e narrative resemblance is due to the nature of ancient Near Eastern creation mythology T h e division of heaven and earth, a

W G Lambert A New Look at the Babylonian Background of Genesis J T S N S 16 (196s) 2( H

-

AN E G Y P T I A N S O U R C E FOR G E N E S I S 447 single act with a double consequence, is the pr imary motif of almost every cosmology of the ancient Near East. T h e identical sequence is therefore no indication of any relationship between the two different accounts beyond their c o m m o n provenance within the ancient Near East. Any justification of a specific correspondence between Enuma Elish and the priestly creation account will need to go beyond this general observation.

W G. L a m b e r t does draw attention to what he recognizes as a significant resemblance between the two accounts. H e maintains that the act of dividing cosmic waters does yield up a valid comparison with Enuma Elish, and that there are no other examples in the ancient Near East at that period. Against that we might press the significance of 'division' for priestly theological reflection It does seem that a precedent for the application of the concept of division to the primeval waters may have been closer at hand than Mesopotamia T h e verb translated by the RV as 'broken u p ' (S7p3) in the flood narrative (Genesis 7:11) seems to be part of an ancient poetic tradit ion of Canaanite origin. It witnesses to a local vocabulary which speaks of 'cleaving' or 'dividing' waters. T h e same verb occurs with those associations in Psalm 74.15 ' T h o u didst cleave fountain and flood'. By extension it comes to be used in the 'mythicization' of the rescue at the Red (Reed) Sea.

In Enuma Elish the particular application of the given creation pattern is the division of Tiamat's watery carcass into two pieces which creates heaven and earth, although some 'fixing' by the deity in both areas is then necessary. In fact the priestly creation account is less straightforward. T h e creation of heaven and earth remains an important and pr imary twin concept, as the opening verse ( i* i ) reminds us, but the management of the waters is more complex. In addition to the account of the 'dividing' of the waters (v 6) which creates the heavens, and has its parallel in Enuma Elish, it contains a separate stage of the 'gathering ' of waters (v 9) which reveals dry land. T h i s is a point of dissimilarity with Enuma Elish W. G. L a m b e r t connects this latter tradit ion to the myth of the Sumero-Babylonian god N i n u r t a who holds back the 'mighty water s ' . 1 6 Perhaps we need look no further than Psalm 104-717 for a parallel T h e provenance of that psalm must concern us later in this discussion. Certainly the management of the waters in the Priestly creation account does not simply replicate that of Enuma Elish.

'^ I xodus 14 16, 21, Isaiah 6$ 12 1 6

L a m b e r t , op cit , 2

-

448 JAMES A T W h L L Once again, the resemblance with Enuma Elish identified under

points [4] and [5] proves on investigation to be more about a shared ancient Near Eastern context than any real identity T h e r e is a significant divergence in detail as regards the managem e n t of the waters which W. G. L a m b e r t connects to Meso-potamian tradit ion m o r e generally, although local Canaanite parallels can be adduced. T h e parallel with Psalm 104 will have to be considered later.

T h e creation of the luminaries [6] is not specific to Enuma Elish, indeed again we can compare Psalm 104:19. However Babylonian influence does appear evident in the commission they are given to 'rule the day' and 'rule the night ' . T h i s does seem to reflect a previous stage in the tradit ion history when it was conceived that the heavenly bodies controlled the fates which in turn govern h u m a n existence. Heidel remarks in particular about the coincidence of the order m Genesis and Enuma Elish in that neither places the heavenly bodies ' immediately after the formation of the sky' 1 7

Certainly we shall have cause to remark on the odd placing of the creation of the luminaries in Genesis 1, but there seem to be good reasons of internal s t ructure in the priestly narrative for their occurrence at the particular point at which they are narrated T h e explanation does not he in an external influence whether from Enuma Elish or elsewhere. T h e interest of [6] therefore is that we can detect an influence from Babylonian ideas as a whole, but not necessarily Enuma Elish specifically.

T h e episode of the creation of h u m a n beings [7] is hardly evidence for any close parallel. T h i s act is likely to come last m any creation account. T h e only similarities between Enuma Elish and Genesis would be that the one sees h u m a n beings created from the blood of a guilty god, and the other in the divine image. But the similarities are not very close. Moreover, the purposes for which they are created are quite different: in the one account for slavery and in the other to exercise dominion T h e two accounts do not appear to come from the same stable

For the final correspondence [8], namely rest, we turn again to W. G. Lamber t . H e declares: ' H e r e Mesopotamia does not fail us ' . H e points out that the rest of the gods after the creation of humani ty is a consistent theme of ancient Mesopotamian myth, of which the Enuma Elish is one witness

O u r conclusion is evident. T h e correspondences m order between the priestly creation narrative and Enuma Elish, as

A Heidel, op cit , }o W G Lambert, op cit , 2

-

AN I G Y P I I A N S O U R C l T O R G L N F S I S 4 4 9

defined by Heidel, are not striking T h e r e are some potential resonances of Babylonian ideas as a whole, most convincingly in the reference to the luminaries T h e correspondence in order is as follows the starting point is the watery primeval deep, heaven and earth are established consequent upon an act of division, further acts of creation include the luminaries and h u m a n kind, divine rest is announced T h a t order of events does no more than witness to a general ancient Near Eastern background to both accounts

2 A comparison of the Priestly Creation Narrative with the Cosmology of Ancient Egypt

We may now turn to ancient Egyptian cosmology It is necessary to enquire whether the specific comparison of the priestly creation account with Egyptian sources yields any interesting resemblances or fruitful insights In order to do this the initial task must be to establish the broad outline of Egyptian creation traditions T h e s e may then be held up for more detailed comparison with the oldest elements of the priestly creation text as identified by Schmidt

In ancient Egypt, throughout the historical period, there were three main centres where particular claims about the creation, or the 'First T i m e ' as the Egyptians preferred to call it, were made T h e s e were H e h o p o h s , M e m p h i s and H e r m o p o h s F u n d a mental to all three were certain basic assumptions about the watery abyss, known as the ' N u n ' , and the 'Primeval hill ' T h e analogy of the watery deep was provided by the Nile, its annual inundation flooded the Nile valley which seemed to be overtaken again by watery formlessness As the waters subsided the hillocks began to appear, their slimy m u d glistening in the sunshine, rich with fertile potential

T h e most influential creation tradition was that devised by the theologians of the sun-god Re at H e h o p o h s T h e y identified Re with the local god A t u m A t u m was ' the great he-she', the source of creation, he took his stand on the primeval hillock He was identified with the majestic sun-god Re who rose every morning over an ordered world as a sort of re-enactment of the First T i m e T h e Egyptian mind from the establ ishment of the Hehopohtan religion onwards never failed to be fascinated by the way the rising sun coaxed the order of the natural world into life T h e petals of the lotus flower opened, the birds flew, the fish

1 9 Coffin Texts }6

-

4 5 0 J A M l S l A 1 Wl L I

darted in the river, humans went to their work and darkness was driven out

Memphis was the ancient capital of a united upper and lower Egypt Its local god was named Ptah, throughout Egyptian history he remained one of the few candidates for the office of high god Originally a chthonic deity, in one of his aspects he is actuallv equated with the primeval hill Numerous inscriptions in the Theban temples of the Greek period record him as a craftsman or smith who works in metal The Shebaka Stone famoush records unequivocally the claim for Ptah of creation by the word

At Hermopohs the qualities of the primeval ocean seem to ha\e been personified in terms of four pairs of godsthe Ogdoad or the Eight The antiquity of this tradition is witnessed by the ancient name of the place which was 'Eight Town' (Shmun in

Coptic) given in heiroglyphics d s . v \ These pnme\al

deities were male and female forms of four different features of the watery abyss These primeval deities were imagined to have forms that were appropriate to creatures of mud and slime, the males were credited with frogs' heads and the females with heads like serpents Their achievement came to be understood as the creation of light, from which the known world could emerge

These three traditions, although distinct, did not develop without mutual interaction as their shared characteristics indicate Certainly by the time of the New Kingdom when it was fashionable to equate the major deities, Amun, Re and Ptah, in a sort of trinity, the great creation traditions were harmonized also Inevitably there remained conspicuous seams and incongruities

Let us return again to the starting point of our investigation in the text as identified by Schmidt His omission of the \erv first verse of Genesis from the primary material has a significant interpretative effect It leaves verse 2 unqualified, and consequently presents it as in toto a description of the pre-creation condition Only subsequent to verse 2 does the initiative of creation commence If this is indeed the true nature of verse 2 in the full biblical text it is a very important point to establish if one is to understand and interpret the verse and its significance correcth Such an interpretation would make it impossible to understand the final description of the primeval state 'and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters' as in some wa> adversative

The Hymn of a Thousand Strophes IV 21 and 22 Pap Laden I ^ o I ranslation from W Beyerhn (ed) Near I ast(m RihgwusTixts (I ondon ig~S)

2S

-

AN E G Y P T I A N S O U R C E F O R G E N E S I S 4 5 1

and contrasting that element over against the unformed primeval state, as, for instance, U Cassuto argues: 'Although the earth was without form or life, and all was steeped in darkness, yet above the unformed matter hovered the (rah) of God, the source of light and life'

It seems impossible to establish the relationship of Genesis m with the following verse on grounds of syntax alone. For instance E A Speiser states' ' T h e first word of Genesis, and hence the first word in the Hebrew Bible is vocalized as ber}st. Grammatical ly, this is evidently in the construct state ' . But W. Eichrodt reaches the opposite conclusion* 'If we unders tand ber'st in Genesis 1:1 as absolute, this is not an arbitrary judgement ' . Von Rad makes his decision that v. is a main clause on theological grounds . H u m b e r t assumes the construct state, but still leaves the description of the pre-creation condition in toto as pr imary: 'Le seul traduction correcte est donc: " L o r s q u e Dieu commena de creer l 'univers, le monde tait alors en tat chaot ique" '.

T h e valid point is made by C. Wes te rmann that comparison with Enuma Ehsh and other creation narratives clearly identifies a traditional pattern that commences 'When there was not yet .. ' and describes in negative terms the situation before the creation On grounds of comparison with ancient material he therefore separates off Genesis 1:1 as a sort of prelude. Th i s argu-ment seems decisive. Genesis 1:2 is correctly unders tood as in toto a description of the pre-creation condition. Any real parallel will need to throw some light on how the spirit of God can be included within that category

Genesis 1, Enuma Ehsh and Egyptian tradition have this in common. They describe the origin of the world as watery, and the pre-creation state in negative terms. It is helpful to hold up for comparison from ancient Egypt the creation tradition from Hermopohs At Hermopohs , we have noted, the qualities of the

U Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Genesis, Part I, ET (Jerusalem 1961), 24 [Hebrew (1944)]

E A Speiser, Genesis, i2 2 3

W Eichrodt, 'In the Beginning A Contribution to the Interpretation of the First Word of the Bible', reproduced from Israel's Prophetic Heritage Essays in honor of James Muilenburg (New York, 1962), in W Anderson (ed ), Creation in the Old Testament (Philadelphia and London, 19X4), 72

2 4 G von Rad, Genesis (London, 1961), 48 [translation of Der erste Buch

Mose, Genesis (Gottingen, 19^8)] ^ Humbert, "Trois notes sur Genese ', Interpretationes ad Vtus

Testamentum pertinentes Sigmundo Mowinckel missae (Oslo, 1955), pp 85 96 26

C Westermann, Genesis -11 A Commentary (London and Minneapolis, 1984), 94 [translation from second German edition, Neukirchen-Vluvn (1976)]

-

452 JAMES E ATWELL primeval deep were personified by four pairs known as 'the Eight'. Its watery state was expressed in the pair known as Nun and his partner Naunet. The deep was further described in negative terms through the divine partners Huh and Hauhet who represent the 'boundlessness' of the great deep.

inm 1) ('without form and void') in Genesis 1:2 is part of that general witness; this interpretation has been challenged by D. T. Tsumura. He denies that these words should be understood as a sort of technical description of the chaotic state. He refers them simply to the earth ( f ^ N v. 2) which is as yet infertile and uninhabited. In his linguistic analysis he underestimates the significance of the context of Genesis 1:2. He does not allow that the 'not yet' pre-creation condition of earth defies description and in some sense redefines any vocabulary brought to it. It is true that 1 occurs on its own a number of times in the Hebrew Scriptures and describes the desert waste. However the addition of 11 forms a sort of hendiadys,2 9 which is perhaps a specific description for ideas associated with the primeval deep (cf Jeremiah 4:23). It is identified by both Gunkel and Cassuto as possibly an ancient poetic expression describing the primeval deep. Its concept is basically of formlessness.

Genesis 1:2 further identifies darkness as of the essence of the pre-creation condition. This holds true throughout the ancient Near East. A. Heidel argues: 'In Enuma Elish this conception is not expressly stated, but we can deduce it from the fact that Timat, according to Berossus ... was shrouded m darkness'.30

For knowledge of the tradition of Hermopohs with its four pairs of primeval deities we are indebted to the priestly theologians of the Greek and Roman period who left inscriptions on the temple walls at Dendera, Edfu, Philae and particularh Thebes The most telling piece of evidence for the antiquity of the tradition is the name of Hermopohs itself, in Coptic Shmun (Eight Town) From the time of the Old Kingdom when the deity Thoth is referred to as lord of his town, it is of 'the (town of) Eight' The Eight are twice invoked in Coffin Text Spell 76 surviving from the Middle Kingdom

D Tsumura, The Earth and the Waters in Genesis 1 and 2, J SOT Supplement 83 (Sheffield, 1989) He takes the mention of 'earth' in Genesis 1 2 as definitive for the significance of the creation account (p 162) The desolate and empty earth (1 2) becomes a place of vegetation ( i n ) and habitation (animals 1 24, and humans 1 26) However, rather than earth as described in \ 2, it is the firmament (v 6) and the earth (v 9) which as the totality of heaven and earth (cf 11) is definitive for the whole account The vision of the priestly creation account is more than utilitarian, and is not comprehended in simply creating an environment around human beings

E A Speiser, Genesis, 5 A Heidel, The Babylonian Genesis, 101

-

AN F G Y P T I A N S O U R C F F O R G F N F S I S 4 5 3 John Day points out that this was t rue of Canaanite concepts as well H e states

That the connection between Leviathan and darkness goes back to Canaanite mythology may be surmised from the Ugantic texts, where in C T \ 6 vi 44 ff (=KTU 6 vi 4s if ) we read that Kothar-and-Hasis, who it is hoped will defeat the dragon (iww=Leviathan), was also the friend of the sun goddess Shapash who is apparently threatened by the dragon

However, it is in Egypt that we find explicit witnesses to darkness as a feature of the primeval deep In the tradit ion of H e r m o p o h s the third of the four divine pairs that personify the chaotic state, known as Kuk and Kauket, represent precisely thick darkness

T h e real problem of interpretat ion that we face in trying to understand Genesis 1 2 lies in the description of the final e lement of the verse H o w can the 'spirit of G o d ' be unders tood as a description of the original, unformed primeval state? A way out of this di lemma could be to translate DTi/K 1 as 'wind of God', but S Childs denies this possibility on the grounds that such a meaning occurs nowhere else in the H e b r e w Scriptures Against this may be argued that Genesis 1 2 is a special case, and so perhaps parallels do not hold J o h n Day appeals to the presumed Canaanite background to Genesis 1 H e argues that we meet here in m u t e d form the wind with which Ba'al equipped himself for the battle with the sea monster, and consequently already have an intrusion of the power of creation H e draws a parallel with the turning point in the flood narrative where the wind of G o d blows over the earth and the waters subside (Genesis 8 1 ) But decisive for our investigation m u s t be that all indications seem to make it unacceptable to break off this phrase from the total description of 'When there was not yet', and give it an adversative sense Any acceptable interpretat ion must be able to explain it in the context of a series of representations of the primeval abyss

Another suggestion is that of E A Speiser who interprets the whole phrase as an 'awesome wind' , taking TI7X in a superlative sense This interpretation is adopted in some modern transla-tions including the N E B 'and a mighty wind swept over the

J Day God s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea (Cambridge 198s) 4S 32

As does H M Orlinsky I he Plain Meaning of R U A H in Gen 1 2 jfQR NS 48 (19^7/^8) pp 174 82 He notes in particular the significance of the four winds created by Anu in enabling Marduk to triumph in the Enuma Ehsh He also draws attention to the use of in J s primeval history (Gen 3 8)

S Childs Myth and Reality in the Old Testament Studies in Biblical Theology 27 (London i960) ^s

E A Speiser Genesis s

-

4 5 4 J A M E S E A T W E L L

surfce of the waters ' . [Included under a marginal note in REB] But that solution strains the text and leaves DTI /X unrelated to its other occurrences in the adjoining verses H Gunkel looked to the verb *"|, to which he gave the sense of 'brood' , for a solution. H e traced the original significance to a Phoenician myth of the cosmic egg. Nei ther suggestion seems to resolve our di lemma. We still have to look elsewhere

We have noted how three of the pairs from the creation tradition of H e r m o p o h s correspond with the description in Genesis 1:2. Can the fourth pair throw any light on our present enigma? H e r e K. Sethe has boldly maintained that the witness from the Greek period to A m u n and Amaunet as the fourth pair of the Eight is to be regarded as a late witness to ancient tradition He seizes on the creative combinat ion of A m u n , the 'hidden one', as primeval deity and A m u n the mysterious high god of the New K i n g d o m represented in the unseen but dynamic power of the wind. According to Sethe 's picture, therefore, A m u n and his par tner represent the dynamic quality of the primeval abyss A m u n is that quality which overcomes the torpor, languidness and stagnation of the primeval waters*

At first calm and motionless, hovering over the sluggish primeval ocean Nun, invisible as a nullity, it (the air) could at a given moment be set in motion, apparently of itself, could churn up the Nun to its depths, so that the mud lying there could condense into solid land and emerge from the flood waters, first as a 'high hillock' or as an 'Isle of Flames' near Hermopohs

If this case put by K. Sethe can be maintained, then, at a stroke, the final element in Genesis 1.2 makes complete sense as a description of the pre-creation condition. H e r e only in the ancient Near East do we find a precedent that might enable us to make sense of the dynamic spirit of G o d as actually a feature of the primeval abyss.

T h e r e is, however, a problem in connection with the witness to the fourth pair of the Ogdoad of H e r m o p o h s Although the Pyramid T e x t s do present an early witness to A m u n and Amaunet as primeval deities, there is no early explicit witness to them as m e m b e r s of the Ogdoad. F u r t h e r , that they may have been inserted

This solution of Gunkel seems to be adopted by J Skinner, Genesis, i8 However it is generally agreed now that the word involves movement (cf Deut 32 11, 'hover' or 'flutter') The Ugantic cognate 'describes a form of motion as opposed to a state of suspension or rest', A Speiser, Genesis, 5

Sethe, 'Amun und die Acht Urgotter von Hermopohs', APAW 4 (i()2o), 42 paragraph 80 Translation from S Moren/, Egyptian Religion, i~6

-

AN I G Y P T I A N S O U R C l P O R G E N E S I S 4 5 5 into the Eight dur ing the long development of the H e r m o p o h t a n tradition seems likely T h e y represent one variant pair amongst other candidates for completing the cosmology, a pair that has come to predominate in the late witness of the temple texts of the Greek period However, it is known that A m u n in his form as A m u n - R e was associated with H e r m o p o h s from the i 8 t h Dynasty T h e evidence leads us to conclude that any j u d g e m e n t about the position of A m u n and A m a u n e t within the H e r m o p o h tan system in the Old K i n g d o m or the Middle K i n g d o m cannot be made with certainty T h e case remains open But it does seem a reasonable assumption that by the t ime of the N e w K i n g d o m the creative connections which Sethe identifies are likely to have been made at H e r m o p o h s T h a t is, the combinat ion of A m u n as primeval deity, representing hiddenness in the sense of nullity or negligibility, with the T h e b a n characteristics of hiddenness, as the invisible power of the wind, would have taken place In that case we may say that the cosmology of H e r m o p o h s enabled Amun to be identified not only as the dynamic principle of existence, as breath or wind, but also the dynamic quality of the pr imeval abyss In all likelihood it is A m u n who is the source of the imagery of *TI7X in Genesis 2

We may note a further significant parallel between the cosmology of H e r m o p o h s and that of Genesis which leads us on to the

3 7 See H Altenmuller, 'Achtheif in W Helck and L Otto (eds ), Lexikon der

gyptologie I (Weisbaden, 197s), column 6 The alternative candidates for the fourth pair ot the Hermopohtan cosmology throw further light on the speculation about the primeval abyss The couples in this fourth personification of the primeval deep, like a quantum zero, hover between existence and non-existence Tenemu and his consort represent a quality of disappearance Niau expresses a negative quaht\ in the sense of void or empty Gereh describes lack or deficiency In as much as Amun and his consort Amaunet were a personification of this fourth pair of the Ogdoad the quality of 'hiddenness' should also be understood in a negative sense such as invisibilitv, perhaps almost negligibility

3 8 G Roeder, Zwei Hieroglyphische Inschriften Aus Hermopohs', ASAE

S2 (1954), PP i1** l S 3 9

This conclusion is shared by R Kihan, 'Genesis 1 2 und die Urgotter von Hermopohs , VT 16 (1966), pp 420 }8 Gustav Jequier, 'Les Quatre C\nocephales', in Samuel A Mercer (ed ), Egyptian Religion, vol 2, no ^ (New York i denies that Sethe has proved Amun to have been ongmallv numbered among the Light of Hermopohs However he is convinced by the correspondence of Genesis 1 2 with the four personifications of the primeval deep at Hermopohs and regards as proven the dependence of Genesis 1 2 on the theology of Hermopohs Creation takes place, according to Jequier's inter-pretation, from the inert primordial material under the influence of 'une force trangre' (to be distiguished from the four pairs of primeval deities) who is the god Thoth According to this interpretation, his is the hidden presence behind the opening of the Genesis creation narrative

-

456 JAMES L A rWl LI next stage in Schmidt ' s oldest material (v 4) T h e achievement of the Eight certainly came to be unders tood as the creation of light T h e y were ' the fathers and mothers who created light' It is reflected in the name of the primeval hill at H e r m o p o h s , 'Isle of Flames ' T h e first act of creation was the emergence of light from the primeval gloom It is a further confirmatory indicator of the relevance of the tradit ion of H e r m o p o h s in understanding the priestly creation narrative

T h e separating of the waters (v 7) was a feature which W G L a m b e r t found to unite Genesis and Enuma Ehsh In as m u c h as it points to the original creation as an act of division or separation, then this general notion of the ancient Near East occurs in Egypt too G e b and N u t , the earth god and the heaven goddess, are separated by their father Shu T h e separation of waters is involved in this imagery of the raising up of the sky Shu represents the atmosphere between heaven and earth which exists, according to one popular universal concept, as a sort of bubble in the universal primeval ocean T h e separation of earth and heaven drives back the waters and creates the atmospheric space W h e n the primeval waters are referred to as a pair, N u n and N a u n e t , this identifies the separated waters of the deep above and below the ordered world In this context J Allen draws specific attention to the correspondence between the priestly cosmology and that of ancient Egypt in the key significance of the firmament or vault in both schemes H e refers to the linguistic differentiation between the waters above and below the created world

Both terms for the universe of waters that exist outside this world have in common the hieroglyph ^ >j, representing the vault of the sky This vault is what keeps the waters from the world he Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts speak of 'keeping the sky clear of the earth and the waters' The same image appears in the Hebrew account of creation ( G e n 1 6 7) 4 1

Schmidt ' s next element of pr imary tradit ion continues with 9 H e adopts as the basis of his rendering the L X X in which the waters themselves take the initiative and 'gather themselves into one meeting place' T h a t nuance would well express the fertility of the Egyptian N u n which actually gives birth to the primeval hill T h e picture is in complete accord with Egyptian concepts where the emergence of the first piece of dry land as the waters

4 0 Theb 9SC [ h e b a n t e m p l e texts of the Greek and R o m a n period see

SetheAPAW4 (1929)] 4 1

J Allen Genesis in Egypt ( N e w Haven 1988) 4

-

AN h G Y P I A N S O U R C E F O R G E N E S I S 4 5 7

recede is a universal feature which has been absorbed into all cosmologies It is based on the annual observation of the Nile 's inundation which flooded the entire river valley, and as its waters receded the ground re-emerged with a cloak of rich fertile silt

It may be that one should unders tand i6 , the creation of the luminaries, as the next step in the original development of cosmic older In that case there would need to be some good reason in priestly logic for the present form of the narrative which we shall have to consider later It makes more sense for the sun to precede nature In Enuma Ehsh the creation of the heavenly bodies follows directly from the establ ishment of heaven and earth In ancient Egypt the sun precedes everything else at the first dawn H o w ever, just as there is a certain tension in the Genesis narrative between the creation of light initially and the heavenly bodies only subsequently, so in ancient Egypt there is a tension between Re identified with A t u m the origin of all order, and Re born daily of N u t , the sky goddess, as a subsequent if principal part of that order

T h e sun and moon are referred to in Genesis 16 as 'greater ' and 'lesser' lights Many commentators have noted that these circumlocutions seem like a priestly device to avoid the ment ion of names that had associations with deities of considerable influence in the Mesopotamian world, and who were actually conceived of as exercising rule and dispensing the fates T h e divinity of the sun in ancient Egypt, perhaps still reflected in Psalm 104, where in ig it is the subject of the verb 'to know' ( S T ) , would hardly have accorded with priestly theology either This latter fact may have made this area of the tradit ion vulnerable, and open to alternative influences In that case the Mesopotamian influence was most likely to have acted u p o n the H e b r e w phase of the tradit ion T h i s section certainly reminds us that developments of thought in the ancient Near East are complex and influences from different major civilizations often interrelate as cosmological patterns develop In particular Canaan and Syria were well placed for absorbing influences from both Mesopotamia and the Nile valley

Genesis 1 12, 21, 25 draws on a tradit ion that observes, articulates, classifies and values the mysterious order of the natural world T h e world of living things is not created one by one, or two

In ancient Egypt too, the earth had a power of its own, it could sprout forth The earth god Geb was often painted green to signify this Osiris, too, represented the fertiht\ of the good earth as could Ptah

For the relevance of Psalm 104 for the interpretation of the priestly creation account see below

-

4 5 8 J A M F S t A I W I L L by two as they leave the ark, but rather in whole colonies as thev swarm (v 21 f^ttf ) There is a scientific interest in classification A distinction is drawn between herbs and fruit trees the one dis-persing seed, the other with the seed in it Creatures of water, land and air are differentiated Those of land are placed in three sub-groups These are cattle, creepers, and beasts, that is, domestic animals, reptiles, and wild animals

From the sun' s rise on the first morning of creation, according to the Hehopohtan tradition of ancient Egypt, there issued forth the great complex order of nature, both vegetable and animal Egypt rejoiced in a vision of the rich variety of species, of activities appropriate to day and night, of animals adapted to particular environments of land, sea, or air, and the mysterious powers of procreation hidden in seed or egg or womb The temple walls of the Old Kingdom, the Onomastica of the Middle Kingdom and the hymns of the New Kingdom present a united witness to this vision of order and relationship in the natural world expressed in the significant concept Maat

Ma(at stood for order in every area of existence A goddess, she was regarded as the daughter of Re, her symbol was a feather Nun and Macat in a sense define each other as opposites Nun represents watery formlessness, and Macat the gleaming order of creation on the first morning as dawn breaks Order was thought to embrace society as well as nature and the physical world, politics and botany were related sciences Judges were priests of Macat and wore her emblem When order referred to that moral order of the world that rewards virtuous behaviour, then Ma(at came close to signifying harmony or even providence In the context of nature's order Ma'at approximates to the modern concept of the ecological balance of nature It is this lat-ter interpretation which is relevant in any comparison with the way nature is observed and categorized in the priestly creation narrative

In the sun temple of Nyuserre at Abu Sir the sun-god is hailed as 'Lord of Ma'at' The significance of that is revealed in the Chamber of the Seasons in which the seasons of 'inundation' and 'deficiency'(i e harvest) are represented by figures in human form, respectively female and male Behind these figures the mural is divided horizontally by watercourses and here the activities of each season are reproduced The impression is of a great catalogue identifying and recording the orderly and inter-related arrangement of natural phenomena, that is, things human, animal, and vegetable within their common environment The daily activities of the agricultural life of the Nile valley are all

-

AN I G Y P I I A N SOURCI I O R G P N t S I S i 459 labelled and named A glimpse is given by this excerpt from the description of von Bissing

Sous une tendue d eau on voit un grand arbre auquel un homme a suspendu une gazelle qu'il est en train de dcouper pour le repas des personnes qui sont assises derrire lui, l'une de ces personnes porte a ses le\res une large coupe A gauche de l'arbre et sur deux registres se tien-nent deux ranges d'animaux qui donnent naissance a leur petit dans une region remplie de \egetation et d abres II s'agit d'une vache sauvage, d'une antilope Mendes, d'une gazelle et d'un bouquetin a la range supr-ieure en bas, c'est une panthre, une lionne tirant la langue , et une antilope, or\ leucoryx L'inscription verticale qui se trouve devant ces animaux doit, si je la comprends bien, se traduire ainsi Marcher dans le desert en donnant naissance renouvelant tout 4 4

The chick hatching in the egg is already the concern of the sun-god

La pi XVIII est plus complexe a droite, sur trois registres, trois pelicans sont en train de couver il semble y avoir dans chaque nid trois oeufs qui

sont prs d eclore si l'on en croit le signe \ \ \ des inscriptions 4S

Un/ The insistence that the divine civil service organized the natural world into a proper sequence and hierarchy on the model of the pharaoh's kingdom is typical of Egyptian thinking throughout its long history Th i s sense of order permeat ing all existence and manifest quite marvellously in the natural world enabled the Egyptians to observe and articulate nature ' s harmoniousness and mterrelatedness All things exist in a sort of communion which is broken only at great risk It is clearly that selfsame inspiration that encounters us in Genesis 12, 21, 25 4 6

T h e priestly c o m m e n t which is not, one must assume, part of the original tradition, continually refers to the world m G o d ' s judgement as 'good' p l t t ) H e r e 'good' has certainly developed beyond the primitive and experimental meaning of 'successful' as opposed to 'unsuccessful' which still lurks behind Genesis 2 18 However, there is still a certain innocent joy behind the

V\ I von Bissing I a Chambre des trois saisons du sanctuaire solaire du roi Rathoures (V D\nastie) a Aboursir ASAF s (i

-

460 JAMl S A rWl I I acclamation 'very good' in 31 Von Rad ' s unders tanding of the significance of this word accords well with the basic tradition and identifies its t rue nature The word contains less an aesthetic judgement than the designation of purpose and correspondence (It corresponds therefore though with much more restraint to the content of Ps 104 ^i Ps 104 tells not so much of the beauty as of the marvellous purpose and order of creation ) T h i s correspondence between the original material and priestl} j u d g e m e n t should remind us that in the choice of their raw material these circles had already acquired a vision able to be adapted to their own T h e balance, symmetry and detail of the Egyptian concept of the created order, which was unders tood as seamless with the civil order of the k ingdom under the pharaoh, was sympathet ic to the priestly desire to separate and classify

We must note that the comparison made by von Rad with Psalm 104 is not a casual one T h e r e are a n u m b e r of specific comparisons that have been drawn between Genesis 1 and Psalm 104 Light is a pr imary feature of the Almighty (v 2a) T h e world comes about through the securing of the heavenly waters and the waters u n d e r the earth T h e heavenly firmament of Genesis 1 7 has its equivalence in a heavenly tent (v 2b) T h e foundations of the earth are laid in the waters (v 5), and the earth appears when the waters recede In the case of Psalm 104 they are driven back (vv 6 8) Creation is firmly achieved without any lurking threat to the creator (v 9) H e r e we leave the specific order that we find in Genesis 1, but all of its subsequent features may be identified in the psalm T h e r e are the heavenly bodies marking the seasons (v 19) T h e r e is the world of vegetation including trees (v 16), and the aquatic world (v 25) owls of the air find a ment ion in 12 Various provision is made for food, including dififerent categories for cattle and people (v 14) H u m a n labour and the allocation of wine and bread for h u m a n welfare are also reflected upon

Specific verbal similarities between Genesis 1 and Psalm 104 are also recognizable J Day notes

With regard to verbal similarities it may be noted that a considerable amount of common vocabulary is shared between Gen 1 and Ps 104 Particularly striking are the expression lemo

-

AN F G Y P I I A N S O U R C P F O R G E N F S I S 461 the luminaries), and the form haycto, found in Ps 104 11, 20 and Gen 1 24, and apart from the latter passage attested only in poetry in the Old Testament 4 S

Psalm 104, which could equally appropriately be classified within the biblical Wisdom corpus, provides us with a tool for reflection on Genesis 1 1 2 4 Indeed, as we discuss below, H u m b e r t argues that it is a sort of hymnic response to that text J D a y 4 9

argues in the reverse direction, that Genesis 1 is based on Psalm 104 H e rests his case on the supposedly m o r e primitive nature of Psalm 104, and in particular the fact that it still explicitly carries allusion to the divine conflict with chaos which has vanished from Genesis 1 H e does allow, but does not favour the possibility, that it is conceivable that both Genesis 1 and Psalm 104 could be dependent upon a single c o m m o n tradit ion

We have argued for an Egyptian background to Genesis 1, and such a background for Psalm 104 is not in dispute T h e psalm is similar in form to the Egyptian h y m n s of the N e w K i n g d o m In particular it bears a distinct resemblance to Akenhaten 's Hymn to Aten T h e m u t e d Canaanite-inspired divine conflict with the waters we would see as no more than a cosmetic enhancement of Psalm 104 to bring it into line with prevailing local cultic conventions of the way creation is recounted T h e Wisdom tradit ion was international, but in its local manifestations used the name for God from local tradition and adapted to local colour as regards the way that deity created What remained a constant feature was that creation for the Wisdom tradit ion, in contrast to cultic celebration, was always a completed event 5 0

We would therefore see Psalm 104 and Genesis 1 as witnesses to a single c o m m o n Egyptian-inspired tradit ion, but the absence of conflict in Genesis 1 actually makes it the purer witness T h e attested closeness of Psalm 104 both to the Wisdom tradit ion and in particular to the Egyptian h y m n s of the N e w K i n g d o m can be used as a sort of commentary on the Genesis creation narrative The psalm helps us to unders tand the inspiration and motivation behind the Genesis narrative

J Da> God s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea s J Dav Gods Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea pp si ff and Psalms

(Sheffield iyyo) pp 41 f More generally on Psalm 104 Day summarises succinct^ Psalm 104 is remarkable not only for the length of its concentration on the subject of creation and its striking parallels with the Egyptian hymn to Aton by Pharaoh Akhenaten but also for the way that the order in [which] topics are treated agrees with the order of creation in Genesis 1 Psalms 41

See Hans-Jurgen Hermisson Observations on the Creation Theology in Wisdom in W Anderson (ed ) Creation in the Old Testament pp 118 34

-

462 J M E S E A T W F L L We may end our look at Psalm 104 by noting that it also

includes the progression of night and day (vv 19 23), which is at least a point of contact with the scheme. As creation was achieved in a day in Egypt, this t ime period was most important, and conceived to be, in some sense, repeated each morning. In fact v. 19 begins with the evening. If the sun rises on a gleaming order of creation then the actual regenerative process while the sun bathes in the N u n is from dusk until dawn. T h i s may be reflected in P's cycle 'and evening and morning were the nth day'

Next in the pr imary material we come to the creation of h u m a n beings (vv. 26-7). Schmidt sees this as a unit with a different prehis tory . 5 2 T h e opening: 'Let us make m a n ...' may well reflect this, and in the original circumstance announce the decision of the divine council to make h u m a n beings. It is reminiscent of the divine reflection included by J in his narrative* 'Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil' (Gen. 3*22a) Both retain evidence of a similar archaic stage in their history of transmission. However is perhaps reflecting the plurality of the Ennead of ancient Egypt, rather than the creating deities of ancient Mesopotamia. may have retained the plural form as a 'deliberative' or perhaps because it has a less anthropomorphic ring

T w o specific things are said of h u m a n beings. Firstly that they are in the ' image' ( 7 ^ ) and 'likeness' () of God, and secondly that they are given dominion. Of the first ascription likeness is the weaker concept; it occurs in Ezekiel's vision when he sees ' the likeness of four living creatures ' (Ezekiel 1:5) It indicates analogy. Image has a greater sense of identity It can mean a copy (1 Samuel 6:5) or occasionally an idol ( N u m b e r s 33:52 and 2 Kings 11:18) or even a painting (Ezekiel 23:14). As regards dominion, this is quite strongly expressed. H u m a n i t y is to ' subdue ' the earth. T h i s is taken from the language of the treading of the wine press (Joel 4:13), and also the battlefield ( N u m b e r s 32-22, 29; Joshua 18:1). T h i s latter imagery even leads Brueggemann to extend the concept of ' h u m a n dominion ' to the Israelite dominion of Palestine. If that is the case then P's more domestic and nationalistic concerns are concealed within the creation narrative

51 For a discussion on the commencement of a day see H R Stores, 'Does the

Day Begin in the Evening or the Morning?', VT 16 (1966), pp 460-7s 5 2

W H Schmidt, Die Schopfungsgeschichte der Priester schrift, 128 53

Psalm 8 likewise witnesses to an identical tradition Humanity is made (\ 5) a 'little lower than DTI/X' and given dominion over the rest of creation 'Thou hast put all things under his feet' (v 6) is a strong concept also

5 4 W Brueggemann, The Vitality of Old Testament Traditions (Atlanta, 19S2 ),

ioy

-

AN L G Y P T I A N S O U R C E FOR G K N L S I S 463 T h e dominion theme is repeated with more vehemence in Genesis 9.2, with the associated 'fear' and 'dread ' the animal world will have of humani ty in the new age of violence. We may note in that context that h u m a n beings after the flood have not lost the divine image It is the ground for forbidding h u m a n bloodshed (Genesis 9.6).

M u c h ink has been spent on the nature of the divine image in h u m a n beings, and whether the emphasis is on a physical or spiritual resemblance. T h e linking of the divine image and dominion seems to point us in the direction of ancient Near Eastern concepts of kingship T h e person of the king often provided in the ' h u m a n being writ large' the means whereby the Wisdom tradition could bring h u m a n behaviour and h u m a n destiny u n d e r close scrutiny H. Wildberger draws attention to the form salmu (image) occurring in Babylonian civilization and its application to the king. However he notes that Egypt is richer in such texts ^ Indeed the king in Mesopotamia was never considered divine in the way he was in ancient Egypt. T h e king, like his subjects, groped his way through life seeking guidance and direction from augury and sacrificial entrails for an unders tanding of the divine will. In ancient Canaan, too, the king was more likely to be accorded the wisdom of the 'primal m a n ' than of a god in the full sense. We may note also that the Mesopotamian assessment of h u m a n destiny was hardly compatible with any sense of an indwelling divine image.

Egypt, however, is a different matter . T h e r e we discover that the pharaoh was acclaimed as divine: ' T h o u art the living likeness of thy father Atum of H e h o p o h s for authoritative ut terance (hu) is in thy m o u t h , unders tanding (sia*) is in thy heart, thy speech is the shrine of t ruth (Maat)" S 7 Such descriptions were regularly used of the god-king, who like his divine father at the first t ime, ruled with the companions of god at c r e a t i o n H u Sia* and Ma(atalways beside his throne. When the king appeared on his throne he was spoken of as the divine sun rising from the east When the pharaoh died, like the evening sun, he descended to the horizon. T h i s image was no hyperbole, but a literal understanding of the god-king.

H Wildberger,'Das Abbild Gottes, Gen 126 }o\ TZ 21 (196s), pp 24s S

-

4 6 4 J A M I S I W H I

It is possible to trace a democratization of the funeral rites of the pharaoh, which extended the identification of the king with Osiris to his nobles dur ing the l irst Intermediate Period It would not therefore be surpris ing to find a democratization in some circles of other royal qualities including the divine image Indeed we find in the Instructions for King Merikare evidence that this connection had been made for h u m a n beings in general The\ are his images, who came forth from his body ' 5 8 T h i s was never the official Egyptian 'doctr ine of humani ty ' , but sometimes the humanis t ic tradit ion of the Instructions might dream of h u m a n i t y ' s royal destiny T h e centrahty of the Instructions within the Wisdom tradit ion of Egypt gave to h u m a n s and their behaviour an increasingly central emphasis Indeed the implication of the Wisdom-influenced narrative of Genesis ^ that the misdemeanour of h u m a n beings can have a calamitous effect on the whole creation itself approaches hubris H u m a n beings are there given a position of enormous and pivotal significance, not unlike the position of the pharaoh in ancient Egypt, which certainly corresponds to the royal dignity of Genesis 26 7

If the divine image in h u m a n beings is taken from the Egyptian pharaoh, we certainly have a way into its meaning N o doubt the m o n a r c h would have been accorded physical beautv, as was the case for the royal house even in Israel S 9 But wisdom would have been the pr imary quality, that for which Solomon prayed in such an exemplary way 6 ( ) It would have embraced knowledge, discrimination and the potential for a righteous life T h e divine image in Genesis 1 is not far from the enticement presented to Adam when Eve stretched out her hand for the fruit

and you will be as G o d (^/), knowing good and evil' (Genesis 3 ) Once again we detect the guiding hand of wisdom in presenting and reflecting upon the nature of h u m a n beings as they are before G o d

T h e final e lement in Schmidt ' s basic material is the rest of God (Genesis 2 2) T h i s also finds a resonance in ancient Egypt T h e r e it is not a release from toil for the gods brought about by the creation of h u m a n beings as it is in Mesopotamia Rather it is satisfaction at the conclusion of a job well done It was said of Ptah of M e m p h i s 'So Ptah rested after he had made all things and all the

Instructions for King Merikare verse See W Beverhn (ed ) Near Fastern Religious Texts Relating to the Old Testament 46

cf 2 Samuel 14 2s 1 Kings } -, ff

-

AN E G Y P T I A N S O U R C E F O R G E N E S I S 4 6 5

words of god' 6 1 T h e translation in ANET renders ' rested' with an alternative translation 'was satisfied'. T h e rest of G o d in the Egyptian context relates well to the priestly insistence that the world in G o d ' s j u d g e m e n t was 'good' (31). T h a t is, it was har-monious, ordered, complete, and satisfying. It seems much more in sympathy with the priestly creation narrative as a whole to look to the Egyptian nuance for an unders tanding of the divine rest, than to look to the Mesopotamian notion of the rest of the gods following the burdening of human beings with their work. T h e rest is not so much relief from toil as satisfactory completion of the job . It bears the hallmark of what may be identified as a specifically Wisdom unders tanding of creation as something complete in the past rather than emergent in the present .

Egypt has rewarded us richly as a source for comparison with the oldest elements of the priestly creation narrative as Schmidt has identified them. A question remains. Can Egypt help us at all significantly with the command account, the framework which has come to regulate the action account? T h e rest of Ptah reminds us also of the claim made for him of creation by his word.

Creation by the divine word was a common concept th roughout the ancient Near East. It was not a late and refined expression of the divine activity in creation, but was already a live concept in ancient Sumer . Its origin seems to penetrate deeply into the primitive belief in the power of a name and the magic associated with words Just as an image might partake of the essence of the thing it represented, so the spoken word had the potential of the thing it signified. It is closely allied to the mentali ty that believed a ritual act could actually evoke the reality that it portrayed. Doubtless this way of thinking was decisively reinforced by the experience of kingship in the ancient Near East. After all the king had only to conceive a command and utter it, and the deed was done T h e effective word of the despot provided an analogy for the divine word

The Enuma Elish opens by setting the scene before the creation by talking of a t ime when things had not been 'named ' . Indeed Marduk displays his power in what is as much a s tunt as an act of creation when he proves his word can 'wreck or create' ; that

Extract from the Shabaka Stone, see W Be>erhn (ed ), Near Eastern Religious Texts Relating to the Old Testament, s T h e text is also t rans lated in J Pntchard Arment Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, (Pr inceton, 1969), for this extract see s, co lumn 11 T h e key word is the Egypt ian verb htp which in the I r m a n - G r a p o w Wrterbuch I I I , pp 18S ff is given a range of meanings, beginning with ' to be satisfied', bu t with many examples also of ' to rest '

-

466 JAMLS h A T W E L L is, at his ut terance images appear and disappear. ' But it is in ancient Egypt that creation by the word became part of the official dogma claimed by the priests of both H e h o p o h s and M e m p h i s for their respective deities.

It may be that the ' t radit ion history' of the Genesis creation account is m u c h more of a unity than is normally supposed T h e two strands of action and command, which to earlier commentators seemed so mutual ly exclusive, have existed together in Egypt since high antiquity. As early as the Pyramid Texts , Hu (utterance) and Siay (perception), which provide the conceptual tools whereby the theologians of H e h o p o h s articulate creation by the word for Atum, appear as a pair. In the Coffin Texts this pair is identified with elements of a more physical presentation of the work of creation.

In the N e w K i n g d o m the witness is unequivocal in claiming for A m o n - R e and Ptah creation by the word, but the claims made for both have deeply rooted associations with more earthv and physical concepts of creation. For instance, the Shabaka stone (the inscription reflecting an original dated by J P. Allen to the N e w K i n g d o m ) witnesses to the M e m p h i t e theolog\ T h a t theology represents an exceptional thrust of insight which in the period of the N e w K i n g d o m has already articulated a 'logos theology' Yet the supposed contradictions between an action and a c o m m a n d account of creation cannot be more nakedlv exposed than within this text T h e r e the theology of M e m p h i s , b\ this t ime mixing its sources, equates the ' teeth and lips' of Ptah with the ' semen and hands of A t u m ' T h e ancient tradition which emphasized A t u m ' s self-sufficiency in creation by using the image of masturbat ion sits side by side with the witness to the divine word which actually articulates the self-same theological principle. Both witness to the sole initiative of the creator acting entirely alone. Indeed Ptah, who formed by his word, is both a chthonic deity as Ta-tenen, and a smith. In this latter capacity he would certainly have been capable of h a m m e r i n g out the firmament (lTp*1) of Genesis 1:6 in his workshop

W h e n the template of ancient Egyptian creation traditions is held u p against the Genesis creation account there is a quite remarkable correspondence T h e conclusion is stark and compelling: ancient Egypt provided the foundation tradition which was shaped and handed on by successive priestly generations When

6 Enuma Ehsh Tablet IV, lines 2s 6

6 3 J Allen, Genesis m Egypt, pp 4} t

-

AN I G Y P I I A N S O U R C L F O R G F N E S I S 4 6 7

Westermann c o m m e n d s W H Schmidt ' s s tudy Die Schopfungsgeschichte der Priesterschrift he states

He has established definitively that the first chapter of Genesis had its origin in the course of a history of tradition of which the written text of is the last stage, and which stretches back beyond and outside Israel in a long and many-branched oral pre-history 6 4

This study confirms that the origin of the first chapter of Genesis may be traced through a long prehistory to a source that is indeed outside Israel However that source may not be as many-branched as Westermann supposed Ancient Egypt proves to be the single, coherent and rich source of the priestly creation tradit ions T h e Nile civilization provides not simply a possible context for odd verses, but again and again accounts for the detail of the Genesis creation narrative and is the key to its c o m m o n thread T h e order of the pharaoh's k ingdom was compatible with and resourced the vision of priestly cosmic symmetry

This research has presented a serious challenge to any a t tempt to isolate creation by the word in the priestly creation account from the supposedly more basic material It is likely that the source tradition consisted not only of those elements identified by Schmidt, but also included in some embryonic way a witness to creation bv the divine word T h e hallmark of Wisdom has been detected on a n u m b e r of occasions It seems a fair assumption that the wealth of scribal and intellectual contact in the period of the early monarchy would have given ample occasion for this deposit of tradition, already venerable, to have travelled to the H e b r e w kingdom of David and Solomon and been absorbed into sacred tradition It seems as certain as these things can be that the N e w Kingdom phase of ancient Egypt 's development, through the medium of the wisdom tradit ion, provided our priestly t radents with a single tradition of creation by word and action which they nurtured, refined and tooled into the composit ion which we now enjoy

I I T H E P A T T E R N I N G O F S E V E N

We turn now to our second question H o w does the pat terning of seven imposed upon the acts of creation relate to the tradit ion history of Genesis ?

C Westermann Genesis 8^

-

468 JAMES E ATWELL Something of a puzzle relating to the text of Genesis is readily

discernible. As it stands the narrative unfolds over a seven day period. The final day is the day of divine rest Creation is therefore recounted in six daily episodes This pattern seems to have been imposed secondarily on the material as there are eight creative acts. The eight acts have been compacted into six days resulting in two acts on both the third and sixth days How has this come about?

P. Humbert has argued for a cultic setting for Genesis 1-2.4a. He maintains that Genesis 1 is a dramatic narrative which in its construction reflects how the events of creation were celebrated over a festival of seven days' duration. This, he believes, was Israel's celebration of the New Year, and took place at the Jerusalem temple at the Feast of Tabernacles. By analogy with the reading of the Enuma Ehsh at the Babylonian New Year Festival which concludes with the recitation of the fifty names of Marduk, he sees Psalm 104, prefaced by the concluding verses (vv 19-22) of Psalm 103, which relate to enthronement, as the hymnic response to the creator sung at the festival. He mentions also the mystery plays of ancient Egypt similarly concluding with solar hymns

In support of this thesis, he points to the priestly nature of the tradition of Genesis 1, indications that it was intended for public recitation and liturgical use, and the unnatural organization of the creation material into seven episodes. Further he maintains that the blessings within the narrative and the provision of food for animals and human beings relates naturally to a cultic setting in which each autumn there is a renewal of fertility. The hallowing of the sabbath indicates for Humbert a cultic usage, and he compares the rites of consecration in 2 Chronicles 29*17 He summarises his conclusion: 'Le schma des sept jours serait, en ce cas, la projection sur le mythe crateur lui-mme du calendrier de cette fte automnale et primitivement agraire qui commmorait et oprait le renouveau de l'anne au cours de la premire semaine d i ) 5 6 6 e 1 an .

If Humbert is correct then we have a plausible explanation for the seven days of creation. A similar observation is made by L. R. Fisher when he draws a comparison between the scheme of Genesis 1 and both the building of Ba'al's temple in the Ugantic texts in seven days and Solomon's temple in seven years (1 Kings 6:38). He concludes: 'If these temples were constructed

65 Humbert, 'La relation de Genese et du Psaume 104 avec la liturgie du

Nouvel-An Israelite', RHPR 15 (I

-

A N E G Y P T I A N S O U R C E F O R G F N P S I S 4 6 9

in terms of " s e v e n " it is really no wonder that the creation poem of Genesis is inserted in a seven-day framework' 6 7

T h e problem is that there is no direct evidence, as we have for Babylon in the first mi l lennium for Enuma Elish, for the association of the Genesis narrative with the cult We m u s t take seriously the judgement of W H Schmidt when he can find no evidence that the priestly creation narrative was used as a liturgical text

aber die biblische Schopfungsgeschichte bietet keine Anzeichen dafr, da sie einmal die Legende eines Festes war und irgendwie "begangen" , szenischdramatisch dargestellt wurde ' 6 8

The fact that Genesis was not itself a liturgical text, if Schmidt is correct, does not mean that it has not been s tamped and fashioned by cultic considerations A learned priestly apologia about creation, as Genesis undoubted ly is, would still reflect and give expression to the way in which creation, stability and fertility were celebrated, and perhaps in some way lived through in worship It is unlikely that a priestly narrative account of creation would be totally divorced from the thought-forms and patterns familiar from the cult Indeed it is highly likely that these would provide the framework for learned reflection Indications that this was indeed the case are forthcoming from the priestly primeval history T h e observation of L M Barre is relevant here

s dating the end of the flood narrative on 601 (rather than on 2 27 601) places the establishment of God s covenant with Noah on New Year s Day his parallels s creation account in which the creation of the world was concluded on another day of ritual importancethe sabbath In this way the Priestly writer connected both the creation and the re creation of the world with Israelite liturgy 6 9

We can go this far with H u m b e r t with some confidence It seems most likely that the period of seven days for creation in the priestly narrative presented itself by analogy with liturgical observation However this is not to say that the text as it now stands was ever used as a liturgical piece

The priestly creation text did not appear in its present form 'at a stroke' It has developed through generations of handling, and so has the significance of the seven days and in particular the

6 7 L R Fisher I he T e m p l e Q u a r t e r JSS (n)6i,) 40 W e m a y note in

this context the interest ing b u t not provable suggestion of C Craigie T h e Comparison of H e b r e w poetry Psalm 104 in the light of Egypt ian and U g a n t i c Poetry Semitics 4 (1974) PP i 21 that Psa lm 104 was originally c o m p o s e d for the very feast of I abernacles which saw S o l o m o n s t e m p l e dedicated

W H S c h m i d t Die Schopfungsgeschichte der Priesterschrift 73 6 9

L M Barre T h e Riddle of the H o o d C h r o n o l o g y JfSO 41 (n)HH) i 7

-

4 7 0 J A M S L A T W L L L

seventh. T h e first of the days to contain two acts of creation is da\ three. O n that day both the earth and plant life appear On the previous day the way had been prepared for the creation of land by the dividing of the waters, which is made permanent by the fabrication of the firmament