A Symbolic Europe for Local Acts, by Léa Assouline & Camille Condez

-

Upload

amsterdam-academy-of-architecture -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

2

description

Transcript of A Symbolic Europe for Local Acts, by Léa Assouline & Camille Condez

How can European policy have differentimpacts and applications in two countries ?

by Léa Assouline & Camille Condez-GodziembaPaper O6 & e-learning European PolicyAcademie van Bouwkunst, 2013Followed by Billy Nolan

A symbolic EuropE for locAl Acts

We want to thank Billy Nolan for the follow and com-ments made , the La4sale agency for documents and contacts provided, Pieter de Vries for help brought about the Texel island and Gaelle Kania concerning Oléron is-land.

Thanks

Introduction

This paper is for us part of the e-learning section of the EMILA program. The EMILA program is a Euro-pean master in landscape architecture. Students spend the second semester of master 1 and the first semester of master 2 in different foreign countries. The e-learning is composed of lectures and exercises on the theme of landscape in Europe. For this exercise we had to write a paper about one European policy influencing landscape. We decided to use it as a way to compare our native country, France, and the Netherlands, in terms of land-scape, culture, economy and law. Through this essay, we wish to demonstrate how Europe is a symbolic au-thority giving the first impulse for local action.

We choose to study nature protection policy to see how a scientific approach can be confronted to a multi-dis-ciplinary approach as landscape, and how a protective policy influences the evolution of landscapes. How can a European policy about natural sites’ protection have different consequences in two countries.We choose the Natura 2000 policy which is made to pro-tect birds and other animals’ nesting or living areas. We wish to discover some cultural elements of those coun-tries through the way they apply the same law. What are their similarities and differences in practice ?

To compare France and the Netherlands, we chose to study two sites protected by the Natura 2000 policy, one in France and one in the Netherlands, with almost the same size and issues (tourism, specific environment). We also decided to pick islands because of their special way of evolving. This is why we decided to compare the way to apply the Natura 2000 policy in Texel island and in Oléron island. Those two islands are part of an archipelago and also have the same kind of landscapes with dunes and pine forests and the same issues about the link with the continent, the touristic access to the beaches and the increase of urban areas.

First, we define the main notions linked to Europe and landscape and present the specificities of our study’s sites. Second, we focus on the influence of European and local policies in terms of landscape evolution, eco-nomic and social dynamics. In the last part, we ask our-selves about the future of those landscapes and policies, enlarging our study to European landscape policies and landscape in general.

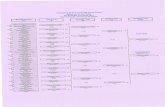

I Definitions...........9a. Main notions...............................................9What is a landscape ?.....................................9Europe, a continent and an ideological entity...11Europe : Which role about landscape ?..........12The pan-European ecological network............15Natura 2000.................................................17Natural reserve..............................................23b. Sites presentation.....................................29Texel, “the bird island”...................................34Oléron, “the bright island”..............................35

II Policies influence..37a. Main issues for Natura 2000, aimes and polemics.................................37b. Comparing nature protections..................41c. Comparing landscapes evolutions............48d. Comparing social and economic impact...52

III Which future ?.....56a. The European landscape convention.........56b. Uniformisation and specidicity..................57

Conclusion...........59

Bibliography& Sources.............61

Summary

9

a. Main notions

What is a landscape ?A lot of definitions exist, evolved over time and comes from several disciplines. Each culture and country might have its own landscape perception.

According to the Wikipedia definitions, today two com-plementary definitions exist about landscape : First, it is considered as a system (studied by geogra-phy, history and ecology) modeled by natural and an-thropological factors. It is also considered as a cultural perspective. Several objects can be identified in a land-scape, but depending on your culture and references, you will not interprete a landscape in the same way2. This shows how complex and interdisciplinary the no-tion of landscape is.

In official texts, landscape is described as a physical area as perceived by people3. This implies two realities, the physical one, on a scientific or geographical point of view, and its perception by the people, which is different for every people experiencing a landscape. Landscape is not defined as a physical thing and different points of view can exist about the same landscape. For B.Pedroli, the landscape is an accumulation of different elements that your mind associates to create your own image of it. To this we can add the notion of time. A landscape is changing depending on the hour of the day, the light, the weather, the nature evolution.

I Definitions

In the common dictionary, landscape is defined as a “spatial area, natural or transformed by Man, which presents a visual or functional identity”1. This definition indicates that actually, any area could be defined as a landscape and that the only specificity is the spatial lim-its chosen to define one landscape.

1 Larousse dictionnary2 http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paysage3 B.Pedroli, European policies

10

• United Nations Conference on Environment and Development : 1992• European Coal and Steel Community : 1951 to 2002• Maastricht Treaty : 1992• Europe : 27 states

11

Europe, a continent and an ideological entity

Geographical and political definitions and evolutions.Europe is a geographical entity : a continent or a part of the Asian continent going from the Atlantic sea to the Oural mountains. As a continent, many different land-scapes, languages, and cultures exist in it.

The European Union is a political and economical defi-nition of Europe but the entire European continent has never been considered as a political unity. It is the asso-ciation of 27 states, existing since the Maastricht Treaty and coming from the 50s economical association ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community). EU has now a political, economical and legal authority on the member states. This implies that local authorities might refer to the European parliament without referring to their nation-al authorities. In that case what is the role of the national authority when a local authority is referring to a European law? Shall we see the national policies as an intermedi-ary between Europe and local actors?

Why Europe as political authority concerning land-scape?Some may say that it is not Europe’s role to define what should be the landscape in each country. Each coun-try often already has protection policies for their natural sites of value. involving Europe might make the protec-tion more complex and European policies may be in con-flict with the existing policies. Also, the policies’ world is closer to a scientific approach that needs a clear cause and effect relation. This makes the creation of European policies about landscape a complex thing. There is not only one way to take care of a landscape. And there is not only one European landscape. So having only one law may be seen as a danger for landscape’s diversity at every scale.

But there is a paradox : the European Union is already taking decisions at the European scale that have a strong influence on landscapes but it is not clearly addressed in it. So if Europe would not be in charge of taking care of its landscape, those policies may have a very nega-tive impact on the European landscape, also in terms of diversity. This is why there is a real need of European policies about landscape. And because landscape is a very blurred notion, those actions have to be made at different levels.

What are the landscape stakes at the European scale?The European landscape is mainly a cultural landscape : it has been modeled by Man for millenniums through clearing forests for agriculture, using the soil resources, creating roads. This landscape is linked to human influ-ence. 75% of the European landscape is an agricultural landscape. This implies that the Common Agricultural Policy, CAP, has a huge impact on the European land-scape. Its one of the most important stakes of European landscape. It is interesting to note that the majority of the European agricultural policies were put in place after the war, favoring the productivity of land. These policies thus have been driving the transformation of European landscapes by intensive agriculture. Today, it is more profitable to do monoculture than small scale farming. This is questioning the plurality of the European land-scape. The European landscape is very diversified : each region has its own model of landscape at a small scale due to geographical and cultural variety of Europe. But, as elsewhere, we observe a homogenization of landscapes and a loss of local specificity, explained by technologi-cal innovations but also by political standardizations. So the political decisions, especially at the European scale, are largely involved in this landscape’s loss or... in its protection.

12

These landscapes form an important part of our cultural, historical and social heritage. Also, landscape is linked to social issues and the link to the ground and landscape is getting lost by people from the city. But people are more and more looking for a certain quality of life and to link their identity to a certain landscape.

That is why, the 80s thus see an attitudes’ evolution. The American model (national parks where people are excluded, except for tourism) shows failures and dif-ficulties to be applied throughout the world, especially in Europe. The roles of native populations in the crea-tion and maintenance of the landscape and its diversity emerged. The ecosystem is no longer seen as a constant equilibrium state, but as a dynamic balance constantly changing, where Human is a part. Therefore, the protec-tion of small and isolated areas is not sustainable if we don’t take into account the interactions between them, or rather between the landscapes that contain them.Since the 80s thus, many global organizations (LCWG - Landscape Conservation Working Group, IUCN - The World Conservation Union, CESP - Commission on En-vironmental Strategy and Planning or IALE - International Association of Landscape Ecology) work to the preser-vation, documentation, identification and management of these areas4. Gradually, these organizations have introduced the prin-ciples of landscape ecology, of planning and of land-scape management... at a local, national and also Euro-pean scale.

As a multidisciplinary thing, landscape makes it difficult to have concrete projects at a European scale : each dis-cipline has its own perception of landscape and its own language to talk about it. But this interdisciplinarity also makes the landscape integrating solutions for many fu-ture issues as economy, social, agriculture or tourism.

This idea of landscape was finally promoted by the Unit-ed Nations Conference on Environment and Develop-ment and then by the Maastricht Treaty. It made changes in policies and practices of landscape protection in Eu-rope. Because the European economies unification and the desire of an economic and social cohesion also means a cohesion of the management and protection of resources and heritage.

Europe : Which role about landscape ?

The European council, which is thinking about ethical issues in Europe, thought of the notion of value of the landscape : people enjoying the landscape are not nec-essarily the one paying for it and the ones maintaining the landscape do not gain anything by doing it5. So the landscape should become a common good with a rec-ognized value. This links the economic and ethical ap-proach and shows the necessity of a common recogni-tion of the landscape’s value at the European scale.

Also today, at a time when we are trying to protect the landscapes and cultural characteristics of Europe, the EU allows to give a broader view of these interactions, at the continent scale, and also to provide the necessary tools for a common understanding and communication.Therefore, the EU ensures a common ideological basis that each country assimilates and adapts to these land-scapes and specificities, into action. This overview al-lows the creation of local actions consistent with each other, forming a network.

Today there is a paradox between the desire to preserve landscapes (cultural and natural) and the need to de-velop Europe, its economy, its cities and therefore its landscape.

13

We know the economic or ecological impact of a legislation, but there is no knowing about the impact on the landscape. The time scale is larger and the changed settings are too many and with very complex connections.As we have seen, manage these landscapes with a single law would lead to their destruction, and create a landscape specific legislation would result in an extreme complexification of their implementation and finally to their no-implemen-tation. The EU can, however, give the common values and indicate the direction in which each country must seek and help them get there.

4 WLO, From landscape ecology to landscape science5 B.Pedroli, European policies

14

These are remaining areas that can come under more intensive land use. But they should still take full account of the success-ful provision of ecosystem goods and services.

Its primary function is the biodiversity conservation. They are usually legally protected under national or Eu-ropean legislation.

These are areas of suitable habitat that provide functional link between core areas. For example, they may stimu-late or allow species migration between areas. Corridors can be continuous strips of land or ‘stepping stones’ that are patches of suitable habitat. Using corridors to im-prove ecological coherence is one of the most important tools in combating the fragmentation that is threatening so many of Europe’s habitats.

Protected areas should not be considered as islands that are safe from negative external effects. The resource use that occurs outside them can have serious impacts on species and habitats within. Buffer zones allow a smoother transition between core areas and surrounding land use.

Corridors

Core areas

Buffer zones

Sustainable use areas

15

The pan-European ecological network

Since the last century, landscapes and habitats are be-coming destroyed or fragmented, losing their ability to provide the required goods and services and species are reducing in number and geographic range. Thus to halt this loss of biodiversity, human resource use must be-come sustainable and integrated with biodiversity con-servation.Ideally, to restore ecosystems, we would be able to pro-tect vast areas from human exploitation. However the demands of economic development in Europe are such that this is not possible even in the last remaining areas of wilderness. The ecological network concept offers a way of reconciling these two conflicting demands by in-tegrating biodiversity conservation with the exploitation of natural resources (see diagram for details).

Europe thus developed a pan-European action plan (be-gan in 1996). The first action was to create this eco-logical network, and the second action involved every economic and social sector in the protection of biologi-cal and landscape diversity, each must then present this plan for the maintenance of biodiversity. A third action was to sensitize the policy makers and the public by im-proving exchanges between specialists and the flow of information through public places (schools, museums, botanical gardens, etc.).

Each member state is thus pushed to carry out ecologi-cal and landscape censuses, to define the most sensi-tive areas and protect them. This leads to the creation of nature reserves, protected sites, and / or Natura 2000 sites. Open these sites to public, means also aware-ness people of each country of their natural and cul-tural wealth. EU is now trying to link more closely this pan-European network and to fight the landscapes ho-mogand enisationlack of actions but also just show its authority to prevent policies’ diversions.

17

6 http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr

Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a European network about nature protec-tion. This network aims to conserve and develop spe-cies and ecosystems that are important in a European context and realizes the survival of specific species and habitats, listed in the European Birds and Habitats Direc-tive. It is a set of European, “ground and marine natural sites, identified for the rarity or the fragility of the wild, animal or vegetal species, and their housing environ-ment. Natura 2000 reconciles nature conservation and the socio-economic concerns.”6. The Natura 2000 network forms part of the Council of Europe’s Pan-European Ecological Network (PEEN). In-ternational collaboration, especially with our neighbour-ing countries, takes place under the umbrella of Euro-parc, the European federation of national parks.

A policy about bird nesting areas already existed since the 70s to protect their environment in different coun-tries (because of the migration) and thus to have a global policy in Europe. After that, the Rio environment’s meet-ing in 1992 focused on the threatened species and the European council committed in creating a protection net-work for those species’ environment called Natura 2000, including the existing birds’ directive. They identified rare or fragile species and decided to protect their environ-ment at a European scale.

Those sites are first identified at a national scale before being integrated in the Natura 2000 network. The aim of this network is to protect but also to value the natural heritage of each region. The application of this policy has to be managed by each country. All European countries have to incorporate these directives’ goals into their na-tional legislation.

19

France contains 1753 sites classified as Natura 2000 areas. Their surface is equal to 12% of the national ter-ritory. The fauna and flora Directive has been adopted in 1992 adding to existing nature’s protections (based on scientific criterias) the consideration of human activities (cultural, economical and social issues) in the aim of de-veloping activities fitting with sustainable development. Some Pilot Comities have been created involving local populations, associations, land owners and municipali-ties to determine the site deserving to be classified and the way to manage them.

The people who want to get involved in the sites’ main-tenance can sign a contract or the Natura 2000 charter. Regular meetings are then organised with the Pilot Com-ity to decide of the maintenance plans. If some projects risk to threaten the biodiversity in Natura 2000 areas, the local authority (prefect, DREAL-land-management di-rection) can intervene against it, anyway every proposal on a Natura 2000 area has to be validated by the Pilot Comity after an evaluation of the impact (filling to pre-established criterias).

21

In the Netherlands, Natura 2000 have been incorporated into the Nature Protection Act and the Flora & Fauna Act since 2005. The Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agricul-ture and Innovation is the responsible and one of the principal funds is the Financial Instrument for the Envi-ronment (LIFE+). The Netherlands presents the characteristic to have wet and rich bird areas on river deltas and along the coast. The European Commission wishes to safeguard that bio-diversity and these homes, developing the Natura 2000 network. There are 162 Natura 2000 sites in the Neth-erlands and half of them are managed by Staatsbosbe-heer (the forest manager), which ensures the opening of these sites to visitors and all the necessary facilities and management for the site and for the well-being of visi-tors. A management plan is drawn up for every Natura 2000 site by the Government Service for Land and Water Management. The plans are dreawn up in close coopera-tion with farmers, municipalities and waterboards.

23

7 D.Lovejoy, Land use…

Natural reserve

The European landscape is mostly made of the contrast between cities and nature, and this contrast is increased when nature is part of a natural reserve. But this opposi-tion between nature and culture is not that true because those natural reserves have to be maintained by human action. For example, most of the natural reserves were made to protect the birds’ nesting area, this may implies to keep the landscape open so the human’s influence is necessary in that case.There is also the question of tourism in those natural re-serve : if a site is classified as a natural reserve it means that its value is recognized so it may attract more people but the increase of visitors might be a danger for nature’s preservation. Paradoxically, these tourists also allow the economic contribution required to maintain those sites.

A natural reserve can be a regional or a national park. In the 70s country and regional parks were developed with the aim of attracting people while preserving some less known sensitive places7. Could the national parks have the same aim to remote the countryside? The dif-ference here is the recreational function : country and regional parks have a designated recreational function whereas national parks are classified because of their “distinctive quality of landscape beauty”. This question of approaching the natural reserve as recreational areas or not has to be linked to those reserves’ context : an ur-banized context would bring more recreational pressure to a site but to have enough money to protect a site, isn’t the recreational part necessary?

25

8http://www.insee.fr/fr/methodes

In France, according to the INSEE (National Institute for Statistics and Economical Studies) definition, “A natu-ral reserve is a part of the territory where the preser-vation of the fauna, the flora, the ground, the waters, the deposits of minerals and fossils and, generally, the natural environment presents a particular importance. It is advisable to subtract to this territory any artificial in-tervention susceptible to degrade it.”8. This definition is interesting because not only taking in account the fauna and flora but also the soil and other elements that permit to extend this definition to landscape’s protection and not only to nature’s one. But what could be considered as artificial in a landscape made by man?

Also, France has several levels of Natural Reserves : “We distinguish the national natural reserves (RNN), the natu-ral reserves of the region with a measure of autonomy of Corsica (RNC) and the regional natural reserves (RNR). Their management is given to associations of nature conservation among which the academies of natural spaces, in public institutions (national parks, Forests National Office) and in local authorities (municipalities, groupings of municipalities, mixed labor syndicates). “As a lot of actors are already implied in those protection’s policies, isn’t Europe a level too? A management plan, drafted by the body administrator of the reserve for five years, plans the objectives and the means to be implemented operated on the ground to maintain or restore the ecological cycles.

The RNR, created on the initiative of regions, replaces the former voluntary natural reserves (RNV). Those vol-untary reserves were dating from the 70s and could be initiated by the owner of the land or local authorities and the decision to classify those sites was taken by the pre-fect. This procedure at a very reduced scale was often diverted by private interests.

This showed the necessity to change it to a regional and national policy. But could we not say that the regional and national commissions might be themselves diverted? Is Europe in that case the member states’ gendarme? Ac-tually, the policy about Natural reserves in France has not been changed with the involving of EU in protection policies so this might mean that the regional and national levels of protection are efficient and sufficient. But in that case what is the role of Europe? Coming back to this idea of a symbolic EU that can lead decisions if there is a

27

9 V.Bus, parcs nationaux (…)

In the Netherlands, the national parks, according to the international agreements from the 70s, are large pieces of land (at least 1000 Ha in the Netherlands) with differ-ent types of ecosystems as less as possible modified by human action and with a biological, geographical, edu-cational or recreational value. The maintenance aim is here to preserve and /or develop the natural and cultural existing values of this landscape9. This definition has the interest to take into account the cultural aspect of the landscape. The maintenance can be made by the work-ing of the land in a traditional or experimental way. The national parks are managed by the Ministry of Agricul-ture. Most of the 20 Dutch National (on the map) Parks were classified as Natural Reserves before that, mostly after private initiatives. The dunes on Texel are classified as a national Park.

The national parks are managed by the Agriculture Na-ture and Food Quality’s ministry, and the government be-gan their creation in 1980. The first one was Schiermon-nikoog in 1989 and De Alde Feanen, completed in 2006 the system of national parks. A total of 20 national parks have been created, and they attract millions of visitors every year. The National Parks have four key objectives : -conservation and development of nature and landscape;- be an area for nature-recreation;- public information and education;- research. Most of these national parks were first classified as Nat-ural Reserves mostly after private’s initiatives.

At the national level, they are linked since 2005 by the National Parks Foundation (Samenwerkingsverband Na-tionale Parken, SNP) and are also part of the National Ecological Network (Ecologische Hoofdstructuur EHS, created in 1990).

As well as promoting cooperation among the parks, the aim of SNP is to improve the quality of the parks. It plans to achieve this by:- promoting exchange of knowledge and experience between Parks;- setting up and coordinating joined projects;- looking after the interests of the national parks system;- encouraging public involvement in National Parks.

At European level, they are part of the Fédération Euro-parc, and most of them are also part of the European Natura 2000 network. In addition to these protections, the Netherlands are also working on the National Eco-logical Network (NEN) to be completed by 2018.The NEN concentrates on the creation of a green buffer with better land use and environmental conditions for habitats and wildlife.

29

b. Sites presentation

Because of their similarity in size, landscape (dunes, wetlands), issues (tourism, urban development, bird’s nesting) and protection (Natura 2000 and regional natu-ral reserve), we chose to compare the islands of Texel and Oléron. Each of these islands has the protections described above, with their own country’s application. Islands in general have a very particular way to develop, both isolated from the continent, and very attractive. This ambivalence gives many different possibilities to apply policies.

30

• Location : Charente-Maritime• Size : 175 km ²• Highest point : 34 m• Length : 30 km• Width : 8 km• Population : 21 871 hab. (2010)• Density : 126 hab /km ²• Links by a bridge

Oléron island

21 871 hab. (2010)250 000 tourists/year

31

• Location : Noord-Holland province • Size : 161,96 km²• Highest point : 30 m (dunes)• Length : 25 km• Width : 8 km• Population : 13 779 hab. (2010)• Density :84 hab./km²• Links by a ferry

Texel island

13 779 hab. (2010)900 000 tourists/year

34

Oléron, “the bright island”

The Oléron Island is the largest island of the Atlantic’s French façade. It is situated in the middle of the west French coast and from the 60s it is linked to the continent by a road (viaduct). It is part of the Aquitain’s basin which means that it is made of sedimentary outcrops from Ju-rassic and cretaceous periods. Then some swamps got formed between those outcrops creating a thin layer of clay. After that, water and wind brought some sand cre-ating the dunes. This implies that the island has three different types of coast (cliffs, dunes and tidal reservoirs / swamps) and thus a particularly rich natural diversity10.

The island presents various landscapes types such as wet meadows, beaches, salty meadows, bocages, dunes, fossil dunes, cliffs forests, lawns, read’s peat, sand willows. One of the interests of this landscape is that the vegetation is laminated with a large variety of birds’ species. This laminated characteristic of this land-scape is strongly linked to human activitie on the site (oyster fields and dune’s fixation..). Which really linked this island to the question of the European landscape as a cultural landscape.

Its lack of relief is also one of this landscape’s specificity in the way it is perceived by people. Moreover, the coast-line is perpetually redrawn by the sea and the wind : the cliffs are eroded and the dunes are moving. Those dune are also very particular because based on limestone’s sands which is unique and provides rare southern plants.Oléron’s beaches are very popular which implies some problem in nature’s preservation : parts of the dune are disappearing due to excessive walking on it, private campings are getting into fallows.

10 O.Gouet, Projet de classement(...)

The island is divided into different protected sites and area for nature or architecture. It is quite strange to see this division between landscape and architecture, espe-cially in such a cultural landscape where the buildings are strongly linked to the use of the land (oyster fields’ small houses…).

rocks dunes beaches forest salt marsh

35

Texel, “the bird island”

Texel is the largest and most populated of the Frisian islands, in the Wadden sea. This island also differs from the other Wadden Sea islands in that the core of the island appearance has been partly shaped by natural processes and partly by human actions. In fact, Texel has not always been an island. After this last Ice Age, it was still a part of the mainland, until 1170 when it broke away from the mainland. Since then, its inhabitants built successive dikes and polders to protect the island from erosion and to expand their lands, until the current out-lines.

This created a wide variety of landscapes with grass-lands, dunes and heathland. Plus the landscapes directly related to human activity as the tulips, windmills, woods, dykes and polders give to the island the reputation to be ‘The Netherlands in miniature’. These landscapes are a subtle blend of natural and man-made landscapes, and they are providing habitats for many birds that are the hallmark of the island.

And today, the human expansion, by urbanization, tour-ism and erosion threatens the variety and richness of its landscapes, especially in the dunes. That is why the Na-tional Park Dunes of Texel was created, with around 43 km² of protected areas. In 2005, thanks to Natura 2000, the Park was involved in a European project to restore 1 100 acres of dunes and manages the environment by an extensive grazing. So paradoxically, in addition to the European protection is also the human activity, with the polders, grazing and tourism that allows the preservation of these areas and the management of the national park.

Today, sustainability is a hot topic in Texel. The munici-pality aims to provide all its renewable energy by 2020. This interest in sustainable development began in 1996 with the Working Group on sustainable tourism in Texel. The initial goal evolved with time and in 2000, the group was renamed Foundation for Sustainable Development of Texel (SDT) and since it initiates and promotes activi-ties directed towards sustainable development.

ancient polders forest beachesdunes

37

II Policies influence

11 D.Lovejoy, Land use (…), p°155

a. Main issues for Natura 2000, aims and polemics

Today, what are the strengths and weaknesses ?+ The Natura 2000 policy is the first policy about na-ture’s protection taking into account (or wishing to take into account) the human activity on and around the con-cerned sites instead of forbidding any activity.

+ Natura 2000 network permits to it to be stronger at the European scale. Each country gives some more strength to it and the national initiatives can also inspire the other countries. All those projects developed by Natura 2000 are in the same aim of developing the ideological value of landscape.

+ Also, having a law at the European scale permits to have an equal fund of subsidies for all countries, mean-ing that even the poorest countries of Europe can now get some money and help for nature development and protections. Nature has no boundaries and should not be related to richness or poverty as a common good for all Europe.

+ A huge benefit for flora and fauna’s diversity has yet been observed in the Natura 2000 areas.

- The limits of the Natura 2000 areas are sometimes not discussed with the inhabitants that then may have a bad opinion of Natura 2000 and so do not get involved in the projects.

- A lot of communication and administrative work is nec-essary, which is complex at the European scale.

- There is a lot of steps and actors to integrate so it takes a lot of time to be very efficiently working

Already in the 70s, D.Lovejoy was warning his readers evocating natural reserves : “policies for protec-tion though planning control are not enough”11. Those poli-cies have to be linked to the increasing of landscape value’s recognition and to local economic interest. Does a policy as Natura 2000 coming from an economic au-thority as the EU answer to this assignment ? Isn’t the local interest forgotten through this global policy ?

38

Does it take into account the economic and social context ?Most of the time the projects about economic develop-ment must be proposed to the Natura2000 committee that then decides if it fits with the Natura 2000 aims. So it is still not Natura 2000 that gets adapted to the social and economical context. Sometimes, the committee deciding of the borders of the Natura 2000 area is composed of inhabitants, farm-ers, people from municipality and others, in that case they can propose limits taking in account the social and economical issues.

Is there applications of the law every time ?The Natura 2000 areas are proposed by the countries and not by Europe so they are always applying the law but sometimes it takes a lot of time to become a con-crete project.

What changes are coming? The Natura 2000 network is increasing more and more, every country wants to have its own Natura 2000 areas and local associations for nature are developing every-where. The people now want more quality of life and get more involved in sustainability and biodiversity issues. This will necessarily have an impact on the development of the Natura 2000 network as a network based on local initiatives.

What are the aims of this policy, are they reachable ?The aim of the Natura 2000 network was first to pro-tect some migrating birds, but those birds are not only migrating inside Europe so the borders are one of the limits of Natura 2000. It is also about integrating human activities in the projects about protection but nowadays tourism and economy are the main aims of populations and it is still often in opposition with nature’s protection.

39

Is it compatible with other protection laws ?Depending on the countries, the Natura 2000 law can replace the existing policies or be added to them. The Natura 2000 policy have the same goals than the others protection laws so it is perfectly compatible.

Is there a design for those Natura 2000 parks ?Natura 2000 areas are not parks but just protected areas that can be on farms, villages, forests. The committee of maintenance can decide of projects at a local scale but most of the time it is lead by maintenance goals and not by design.

Is not there a risk of losing the value of a protected landscape if everything is protected ?The natural areas are more appreciated because of the contrast with the urban areas getting bigger and bigger. The value of nature is now recognized because some diversity is disappearing. What if we protect at the same level all the natural areas as potentially threatened?

Even if there is different levels of protection, will the com-mon people make the difference ? And if every piece of nature is protected, will it still be perceived as threatened and deserving attention from people ?

After some local initiatives and national law, we now get a European network and as Europe is increasing its boundaries, welcoming new countries, this network is also developing. Are not we going toward a world net-work ? Some arguments exist in favor of this, for exam-ple the birds travelling from Europe to Africa should also be protected in Africa. Or could no we create a network of networks ? Some others networks linked to landscape value are appearing, could they be linked and strengthen the Natura 2000 network?Will the European parliament integrate some specialist about landscape in the future ? Now that the value of landscape is getting recognized and that the econom-ic potential of nature’s protection is revealed by some studies, the European parliament should at least ask for some advices of nature’s specialists for the next chang-es in the common agricultural policy for example.

41

b. Comparing nature protections

The landscapes and heritage protection of each island responds to various different logics, methods and ap-proaches. This is evident both in the protected areas development and in their management, but also into the differents protection levels.

The Oléron protections :

On a European level :Natura 2000 (ZPS and SIC)

On a national level :“Loi littoral” (coastal law by the coast conservatory)Natural reserve of Moëze-OléronZNIEFF

On a local level :order of the prefect (classified and enrolled sites)the article L.341.1 of the environment’s codeSCOTT

The Texel protections :

On a European level :Natura 2000

On a national level :Duinen van Texel National parkWeatlands protectionNatural reserve

On a local level :associations (ex of The Lieuw)

42

On a European level : The island contains three areas classified as Natura 2000 : the wet meadow, the swamps and the dunes and for-ests. Those three areas cover almost the whole island. They are classified ZPS (special protection’s area, for birds) and SIC (Site of Community’s interest, for fauna and flora except birds).

• Natura 2000, Habitats + Birds• Dunes and coast forests• Since 2006/2009• Size : 2 904 ha• Managed by DREAL Poitou-Charentes, Ministery, Natural patrimonial service

43

On a European level : Islands, underwater areas and sand strips of the Wadden Sea could not be treated separately. That is why it was decided to create a joint management plan for these ar-eas. The island of Texel must manage three Natura 2000 sites : the Wadden Sea, the North Sea coastal areas and dunes & lowland of Texel.It’s a long and complicated process to implemente this protection : “First we had the EU-directives, then started in 2007 the proces of decission about the exact area and goals to achieve, wich ended by the highest court in 2011. From then on we are talking about an official Plan of Management. It’s nearly ready, I aspect later this year. A lot of organisations and also the inhabitants of Texel participated on it.”The management plan is established to describe the nec-essary steps to manage and preserve the environment. Another part of the plan is to assess the current use of the site, to see if the activities in Natura 2000 area are in conflict with conservation goals. So what were/are the consequences of the natura 2000 application? “Nearly no consequences : there was allready for a long time a quiet strickt protection policy on Texel.”

• Natura 2000, Habitats + Birds• Dunes & lowlands• Since September 2011• Size : 4 615 ha• Managed by the National For-est Service, Nature Reserves, Defence, Rijkswaterstaat (Pub-lic Works) and privates

44

12 O.Gouet, Projet de classement(...)

On a national level : Almost the whole island is classified as “architectural and landscape heritage”, except the villages. Those vil-lages could be classified ZPPAUP (Area of Protection of the Architectural Heritage,Urban and Landscape) to control their extension and protect their architectural her-itage.The tidal reservoirs are part of the natural reserve of Moëze-Oléron since 1993 and the coastline is protected by the littoral swamps’ procedure (from the Coastline Conservatory) since 1991. The swamps are also clas-sified as ZNIEFF (natural area of fauna and flora’s inter-ests), as most of the dune’s forests and wetlands. The ZNIEFF is only an inventory not a protection as itself but it is the base for protections’ policies in France.

45

On a national level :Duinen van Texel National Park has a wide variety of land-scapes : woodland, heath and areas of salt marsh, dune heaths and wet dune slacks as well as dunes of drifting sand. Some places change their appearance under the influence of wind and sea, and it is home to migratory birds.Who was involved into tis creation and what are/were the consequences of its creation ? “Every organisation with interests in the area (province, municipality, waterboard, nature organisations, hous owners, recreative company’s, etc.) participated on its creation, but some people on Texel were afraid of extra regulations and restrictions.But this National Park promots better management, better funding, and more people and organisations involved in protection.”

How is it managed?“There are no people working for the organization Na-tional Park. Different tasks are done by different organi-sations. And some inhabitants organisations in its man-agment, and in communication also directly. Nearly all of the 1 million tourists on Texel every year are visiting the National Park, some are sleeping in the Park (Camp-ings), or just outside in hotels or holiday homes.”13

The managers encourage a permanent relationship be-tween humans and nature. Hiking and bicycle trails, lookout points, picnic and barbeque places and other facilities are also maintained by the National Forest Ser-vice. The areas around the island are also protected by a natu-ral reserve and a wetland protection.

• Size : 4 300 ha• Managed by the National Forest Service and the Defense Ministry• since 1 May 2002

46

On a local level : Protection by order of the prefect for the swamps and woods (56Ha) since 1994 and for the Maratte’s swamps (22,5Ha) since 1995. They are also protected by the ar-ticle L.341.1 of the environment’s code : a list of natural monuments for each department whose conservation or preservation has a general interest (for artistic, histori-cal, picturesque or scientific reasons). Several areas of the island were successively classified under this dé-partement’s list between 1928 and 1990. The district councils also signed an agreement about new buildings’ typologies to maintain the traditional style but this agree-ment is not about the urban extension and does not pro-tect the island from new pavilions outside the villages, buildings on the back of the dunes, linear extensions at the opposite of the traditional grouped buildings12.The SCOTT (land development plan at a local scale) is also trying to control the amount of visitors and cars on the island by taxing the crossing of the viaduct by car.

47

Texel is home to many association, as for exemple The Lieuw. This is an association for Nature and the agricul-tural landscape in Texel, founded in 1998. Initially, Lieuw had only members of the agricultural sector. The Lieuw has evolved over the years to become a full association with numerous collaborations linked to nature and land-scape.Since 2004, the association is financed mainly by the Dutch government. For each contracted hectare, a payment is allocated to De Lieuw. In 2007 some 4,500 ha were under contract and that was approximately half of the agricultural area of the island. Measures focus essentially on the protec-tion of birds. Farmers participate in nest counts and ditch vegetation surveys. Other projects undertaken by De Lieuw include the restoration of characteristic land-scape elements, the improvement of water management in the Polder, farm visits, provision of trail guides and other interpretive materials.

Today, the social instruments are more used to develop a strategy and concrete activities to achieve sustainable development. This methods has made Texel one of the Dutch forerunners in the field of sustainable develop-ment.In 2000 the Texel tourist office (VVV) initiated a partici-patory planning process to discuss the opportunities for future development of the island called “Texel 2030”. The results of this process were turned into a new sce-nario called ‘Texel Unique Island’, where an ‘ideal’ situa-tion is imaginated, on which new policies and decisions are supposed to be based. This vision was published in 2002.

Ona local level :Since a long time Texel follows a strong regulatory poli-cy. The most important of these measures is still applied and no-contested : namely the maximum number of beds that was imposed in 1974. In fact, the implementa-tion of this ‘ceiling’ was the motivation to start a discus-sion on tourism development and to search for alterna-tive, sustainable ways of growth : not the quantity but the quality. As the ‘ceiling’ was introduced at an early stage, when there was still considerable room for development, it was generally accepted. That strategy is a real opportunity for the nature protec-tion, because of the already ‘unused lands’, but also because of the long habit of island inhabitants to limit development and protect its agricultural and natural ar-eas. However, it raises the question of the future devel-opment. How to manage an increase of population? Of housing demand ? Tourism ?

What are the other protections in the island ?The normal spatial regulations (Bestemmingsplannen, structuurplannen), local rules for various activities and events in order to protect the Key-qualities of the island, such as open landscape, darkness at night, nature, cul-ture heritage, etc.

Are there regulations on urbanization, built heritage ?Yes and they are quite strict. Outside the villages it’s nearly impossible to build new houses or company’s. And buildings are protected by national laws and local regulations. It concern a lot of buildings (farms, special houses, typical sheep-sheds) and landscape elements such as little dikes, drinking pools for cattle, etc.

How do they complement / disrupt / associate with the Natura 2000 law ? With the National Park?They suits very well.13

13 Extracts from an interview with Pieter de Vries.

48

c. Comparing landscapes evolutions

• Accessibility In Oléron the Natura 2000 is only at the second step of the project, meaning that there is not yet concrete ac-tions on the land. But most of the protected areas were already natural reserves, protected at local, regional and national levels (several areas were protected by prefect’s order since the 1930’s). The main protected area in Olé-ron is actually the sea between the island and the conti-nent were fishing is forbidden and access very controlled (national preotection). Except that most of the areas are accessible but a lot of activities are forbidden, particu-larly in the swamps and dunes. One of the stakes of Nat-ura 2000 will be to control access to the dunes to avoid erosion due to over-attendance around the beaches in summer.

In Texels, the dunes’ area, which was protected by the National park and now also by the Natura 2000 law, is now only reachable by bike or by feet. Except this, the whole island is accessible (except the private plots). In the dunes the paths are so smaller and sinuous to slow down the cycling people and delimited by wooden fenc-es. Those numerous fences have an impact on the per-ception of landscape and also the sinuous paths make you discover the dunes in a new way (surprises after every bend).More generally, we access to the island by ferry, unlike Oleron where a bridge links to the mainland. This gener-ates different dynamic and amount of tourists. Indeed, many visitors prefer leave their cars on the continent and moves by bike on site.

49

• Dunes’ evolutionIn Oléron, the coastline is perpetually moving : the front part of the dunes evolves with the wind and sea streams. The back of the dunes has been fixated by pines’ plan-tations made by the National Forestry Office between 1920 and late 1960s to avoid them to invade the inside of the island. They now realized that those plantations are decreasing the biodiversity in the island and have stopped them. One of the Natura 2000 projects in this area could be to reintroduce more various trees typi-cal from the dune’s back (sand willows, hawthorn…). Also with the summer huge income of tourists in the surrounding of the beaches in Oléron, some parkings have been installed in the dunes having an impact on the dune’s shapes and evolution. The back of the dunes (also called grey dune) tends to disappear because of erosion increased by tourism.

In Texel, the dunes’ line has been fixed by a sand dike because they tended to disappear because of the in-crease of the sea level and streams. At the opposite of Oléron it is not a moving coastline anymore. The main action, made by the National Park, consist to plant mar-ram grass to fight against sand drifting in the dunes. Grazing animals are also used to prevent the overgrowth of vegetation, but agricultural activities are limited.The access to the grey dune is there forbidden to cars, only a few paths exist and the maangers planted some marram grass to prevent the sand drifting of the dunes, so the back of the dune is not eroded in Texel which permits to have a larger strip of dunes between sea and villages.

50

• Fauna’s diversityThe protection of very different natural areas in Oléron (dunes, swamps, forests, fresh-water swamps…) per-mits to have a global increase of fauna’s diversity, not only for rare birds but also fishes, snakes, amphibians and small mammals.

In Texels the protection is mainly for birds, that are the first tourism’s attraction. The spoonbill that had almost disappeared is now a well-living specie on the island. An increase of insect’s species has been observed since the Natura 2000 protection.In 1851, the dunes row has been breached in three plac-es during a strong storm. One of this water-intake, Sluft-er Kleine, at the south of the island, couldn’t be closed at that time. Today, its fauna and flora value (thanks to the influence of salt water) make that it no longer a question of closing the passage. It is a protected Natura 2000 and the National Park area.

51

• Flora’s diversityThe geological history of Oléron permits to have differ-ent types of grounds and thus different types of vegeta-tion. Also the limestone associated with the geographi-cal position of the island permits to have some plants that we usually only find in the south of France. The national protections already permitted to protect this va-riety of vegetations but the Natura 2000 network may help to inventory some rare species and to find better ways to protect them without forbidding human’s activi-ties around (They recently discovered that some dune’s herbs need the ground to be packed to grow which may imply to reintroduce pastures in those area).

In Texel, only the dunes are protected by Natura 2000 but the size of this strip permits to have a large variety of plants such as salt-loving species like the sea aster and samphire. Sea thrift thrives here too. Around dune water courses we find the marsh marigold. Other places are home to various species of orchids and the delicate bog pimpernel.In the early 1900s the newly established National For-est Service was granted 3000 ha of land on Texel and planted part of this with pine. Now, this forest has been replaced by more various plantations.

52

d. Comparing social and economic impact

• Urban developmentIn Oléron almost 50% of the houses are secondary hous-es and 30% of the tourism housing is in campings. This implies that the island is almost empty during winter. The development of campings permits to avoid building new houses that would threaten the natural areas but as those campings are more open areas that can be used as campings than established campings, they become fallow lands during winter. The district councils also signed an agreement about new buildings’ typologies to maintain the traditional style but this agreement is not about the urban extension and does not protect the is-land from new pavilions outside the villages, buildings on the back of the dunes, linear extensions at the opposite of the traditional grouped buildings.

In Texels there is one main central village and then groups of houses that are more and more developing. Tourists are housed in campings with small bungalows., espe-cially on the west side, behind the dunes. Those camp-ings permits to control urban development and to avoid fallow lands but they are now developing so much that they can be compared to small new villages and thus should be controlled as urban development. And as in Oléron, majority of this tourists housing look similar, without any link with the site. How to control such de-velpment ? On the other hand, the great variety in the shape of the fields, woods, etc, that emerged over time on Texel has been greatly diminished by the ongoing processes of land consolidation and field enlargement initiated in the 1960s. Anyway, agriculture is still an im-portant economic value for the island.

53

• Tourism’ evolutionOnly 4% of Oléron’s population is working in agriculture while 10,6% is now working in tourism. This shows an inversion of the land use from agricultural activities to tourism. Tourism is multiplied per 4 between june and September, this is linked to tourism activities : the main tourists’ activities in Oléron are first going to the beach, then visiting the sites and in third position biking. The SCOTT (land development plan at a local scale) is also trying to control the amount of visitors and cars on the island by taxing the crossing of the viaduct by car.Which evolution with the Natura 2000 ?Maybe the future projects linked to Natura 2000 will make It evolve toward a “green” tourism more oriented to the forests and respecting more the dunes.

In Texel, tourism provides 25% of direct employment and 80% of indirect. The current turnover is around 260 million euros (65 euros per day and 4 million nights).Tourism is thus the mainstay of the economy of the is-land. And it will continue to be it in the years to come, Texel wishing to develop sustainable tourism.

55

• Activities linked to landscapeThe main threats concerning landscape in Oléron are the abandonment of the oysters’ farms, water’s pollu-tion, degradation of the water system linked to the de-crease of use and maintenance and the tourism which can bother the nesting birds and pack down the ground (stopping some plant’s growth). Moreover the freshwater swamps which are less rich in terms of flora and fauna are threatened by the urban pressure because they are between the villages and the beaches. The decrease in agriculture (not profitable any-more at this small scale) and the splitting of a landscape favor the fallowing of the land.This shows that the nature’s protection policies, even at a European scale, are not sufficient to protect a land-scape which is mainly cultural and the Natura 2000 pro-jects in Oléron will have to deal with the reintroduction of some traditional activities linked to landscape such as salterns. Those traditional activities may also become a new attraction for tourism.

Texel especially has to maintain his dune fringe, and here again, the protection laws are not enough, since as seen previously, plantations are needed to limit his disappear-ance. The island is also emptied of its farmers, due to the lack of land profitability.The main concern comes from the steady increase in soil salinity, which directly affects all areas of the island. Whether for drinking water, agriculture, or wildlife in place, freshwater is an stake for Texel.Its researches and activities development related to sus-tainable development and renewable energy is directly related to its landscape.

56

We have seen that concerning Oléron and texels, a lot of projects still have to be done . A lot of possibilities exist now and will evolve in the future with the evolution of mentalities and regulations about landscape at European scale. What will be the future stakes of Europe concern-ing landscape and which new tools are developing?

a. The European landscape convention

The European Landscape Convention is made by the Eu-ropean council, which is quite different to the European Parliament : The European Parliament takes decisions about the economical policies and the Council of Europe is more thinking of the ethical questions. It was created after World War II to prevent from new wars and to pro-tect the Human’s rights. It has a very strong ethical ap-peal but no money.

They realized that landscape is a result of our society and that the laws have a strong impact on it so there is a real necessity of thinking of the European landscape. They approached landscape as a human right : this im-plies the right to enjoy the landscape for everyone but also implies that landscape worth to be maintained. They expressed the necessity to get an explicit value to landscape and to make landscape a common good, in opposite to the present approach of landscape as sever-al lands owned by people. This is the complete opposite of the economical approach of the European Parliament.

In March 2004, 24 countries ratified this European Land-scape Convention, surprisingly Germany and Austria did not. They were probably afraid that money of nature protection may go to landscape protection and also this

III Which future?

57

convention implies strong responsibility about landscape and they do not want more responsibilities. If landscape is a human right and their landscape gets damaged by some of their law, might they be judged for it? Also they say that because they are federal states it would make decisions more complex at a national scale.

At a governmental level this convention now implies reg-ular meetings about the landscape’s state and the best way to maintain it… but still no action. However this convention permits to have interdisciplinary researches about landscape in a global way, which is a good evo-lution for the European landscape even if this does not lead to actions yet. What is needed now is to add design researches to those teams and to act for landscape in each country.

b. Uniformisation and specidicity

The risk of any regulation, particularly at European scale, is to create a standard that everybody has to respect for a better global functioning. But concerning Natura 2000, this would be equal to standardize the natural areas protected and lead to erase their specificities. The protection would thus have the opposite effect than wanted. Natura 2000 also must be watchful not to wrap those spaces in cotton wool be-cause stopping the evolution of those ecosystems, also stopping the human acts on it, would lead to their de-struction.It thus seems that a very large and flexible regulation, adapting to every different situation, is an ideal solution.

Which limits?Natura 2000 is also a network of protected sites. How could manage a continuity between those protections?

Has the whole network the same requirements? How can we deal with the borders of those protections?

This network is clearly showed by Natura 2000 as a Eu-ropean specificity that does not stop at countries’ bor-ders. But those limits can still be questioned : do they stop at Europe’s borders? Are they linked to out of Eu-rope’s protections ? If yes, this would mean for this net-work a non-stopping extension, always including more and more space under its protection.If the quantity of protected areas is too high, is not there a risk to make those sites harmless ? Protection would become the new standard and sites would risk to lose their attractiveness. When would the network end ?

Toward a network of networks ?At a time when climate changes, resources’ manage-ment and sustainability issues get worldwide, and when ones’ acts have consequences on others, protecting our landscapes and their specificities gets newly important.We can imagine a series of networks’ groups, including different countries in every continent. Each network tak-ing in charge the maintaining of its specificities but also a worldwide continuity, being connected to its neighbors. Do we get toward a network of worldwide specificities?

But this network is also a link between actors, inter-nationals, nationals or locals. Those lasts particularly are the warranty of the network non – homogenization. Through their acts and knowledge of the site they are liv-ing in, they permit to maintain its specificities. However, we notice un miss of link and exchange between the na-tional, local and international actors. They all could learn and gain a lot by getting inspired by each others. They could have discussions about local projects or simply exchange some ideas and knowledge about natures’ protection.

59

ConclusionOn Oléron and Texel islands, the Natura 2000 sites are combined with many other protections. This plurality of regulations can complicate the understanding of a site but also risks to hide and reduce the impact of Natura 2000. Which is more profitable for them by facilitating the exchanges of knowledge and acts between different countries’ actors.

However, Natura 2000 is particularly efficient and its effect is clearly visible in the newly European coun-tries. Often rapidly expanding and getting their society changed, they also see their landscapes changing a lot. Landscapes and ecosystems needing to be protected and known through the Natura 2000 policy.Comparing the application of Natura 2000 in one of those young European countries would permit to identify more clearly the impact and gains of this European policy.

In Oléron and Texel, we can notice the similarity of their aims : preserving fauna, flora and their own ecosystems ; making the sites more accessible to public and sharing their knowledge with visitors. Sharing their knowledge at an international level and including populations to the projects are the future aims of those sites. This group of aims is answering the needs in terms of conservation of diversity and specificity of each island.The main difference between those islands is that each one has its own strategy and method of protection. His-tory and culture of the country thus have an essential role in today’s land management.

In France, every administrative level (state, region, de-partment, group of communes, communes), has its own specific protections policies. Those protections, even if they agree with each other, generate a complex system where protected areas get stacked. Natura 2000, as the last policy, only have a few impact on a site already full of protections. More than its financial and cultural contri-bution, Natura 2000 essentially permits to link this area to the European network.In the Netherlands, Texel has been early subjected to a strict regulation limiting urban development on the is-land. Previously the national parks were the main land protection while nowadays Natura 2000 permits to link the threatened areas to a larger scale (as the Waden sea).

So each country gets profit from this policy while adapt-ing it to its own needs. This leads to different applica-tions for a common result : the creation of the Narura 2000 network.Nevertheless, this European network contains a risk of homogenization of future landscapes. But its flexibility (no direct act, every project is made with local and na-tional actors), associated to the local actors’ acts and exchanges, permits to preserve the differences and strengths of each site. Today, the European Union would thus be a symbolic au-thority which would give the impulse and the necessary help to local realizations.

But we still can ask if this system (from Europe to local) should not get inversed (from local to Europe) in the fu-ture to help preserving each country’s specificities.

61

Books

about Europe• N.Hazendonk, H. Van Djik, Greetings from Europe, O10 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2008• D.Lovejoy, Land use and landscape planning, National parks, International textbook company, 1973• B.Pedroli, European policies (lecture), Akademie Van Bouwkunst, 2012• WLO, From landscape ecology to landscape science, Proceedings of the European congress “Landscape Ecology : things to do – Proactive thoughts for the 21st century”, Klijn & Willem VOS, 2000• Euroscapes, Forum 2003, Must Publishers, 2003

about Texel• V.Bus, Parcs nationaux, la politique néerlandaise des parcs nationaux, Ed. du Ministère de l’Agriculture, de la Gestion de a Nature et de la Pêche

about Oléron• O.Gouet,Projet de classement au titre des articles L.341-1et suivants du code de l’environnement de l’île d’oléron, Direction régionale de l’environnement Poitou-Charentes, 2007

Websites

about Europe• http://europa.eu• http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/• http://landscpae-eurpe.net• http://europanostra.org• http://www.euroscapes-eu.org• http://www.europarc.org• http://www.countdown2010.net

about Texel• http://www.natura2000.nl• http://www.government.nl• http://www.nationaalpark.nl• http://www.npduinenvantexel.nl• http://www.texel.net• http://www.staatsbosbeheer.nl• http://www.globalislands.net

about Oléron•http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr• http://www.observatoire.en-charente-maritime.com• http://www.reserves-naturelles.org/rnf

Bibliography & Sources