A Critique ofuonblogs.newcastle.edu.au/.../44/2016/03/Adrian-Lamande-Tiger-Bhu… · responsive to...

Transcript of A Critique ofuonblogs.newcastle.edu.au/.../44/2016/03/Adrian-Lamande-Tiger-Bhu… · responsive to...

A Critique of

A Report By: Adrian Lamande

1

I had heard a lot about Gross National Happiness in Bhutan. How people, including many from more eco-centric

viewpoints, held Bhutan as a model for sustainable development. How could this be? Delving into the complexities

of tiger management in Bhutan was a revelation. At first glance Bhutan’s Tiger Management Plan looks no different

from other plans developed in other countries. It contains elements of vagueness, reliance on scientific knowledge

and top-down management. However, when I looked further, I discovered that it needs to be viewed in the context

of Bhutan’s unique development program; one that places equal emphasis on intellectual, emotional, spiritual and

economic development. Looking even deeper, it became apparent that this too is based on a deeper values system,

one stemming from a uniquely Himalayan approach to Buddhism. This deeper value system is one that views the

world as an illusion of reality.

So how do you critique a management plan within this context? The complexities are enormous. It sits within a

unique development model, within a unique culture. They all recognise the importance of a holistic approach to

almost everything, and are exceedingly complex in their connectedness. There is an inherent understanding that the

only way to achieve anything is to understand complexities, and externalities exist as a fact of life itself. This

recognises the impossibility of achieving tiger management (or anything for that matter) within the scope of any

particular jurisdiction, department, corporation, industry, community or lifetime. It’s the ultimate multi-agency

approach. Even going beyond this, it permeates every crevice of life and community and adds bits of deliberative

democracy, community involvement, and spiritual understanding. This management approach is beautifully complex,

yet beautifully simple, beautifully entwined, yet beautifully clear.

Therefore, critiquing Bhutan’s tiger management plan requires critiquing their development program, culture,

religion, construction of reality, and way of life. It is an attempt to understand an extremely complex, intertwined

and holistic system. This is the problem this report faced.

How could something be so simple, yet complex? How could a management plan be so intertwined with every aspect

of every life? This is because many recent western discoveries regarding resilience and uncertainty have existed for

thousands of years in the indigenous cultures of the Himalayas. Bhutanese culture recognises there are so many

shades of grey that no one could ever see them all.

Adrian Lamande

2

Tiger management is complex. It needs to account for the myriad of complex

interactions that occur within nature, society, and the economy. Bhutan faces

many challenges; the country is developing, their population is growing, and

their people are dependent upon forest resources. However, Bhutan’s

development strategy and culture provide a unique framework to achieve

tiger management.

Bhutan is one of the only truly indigenous forms of governance, top to

bottom. Bhutan’s tiger management plan fits within this framework and they

are impossible to separate. This holistic and complexly-connected structure

provides an opportunity to achieve sustainable development. It is why the

plan is working. It provides an opportunity for other countries to learn from.

However, Bhutan needs to be careful the influences of continued

development and global interaction do not undermine this unique system.

3

INTRODUCTION | 1 4

BHUTAN’S TIGER ACTION PLAN | 2 5

Tiger Management in Bhutan | 2.1 5

Bhutan’s Answer to this Complexity | 2.2 7

Problems with the Plan | 2.3 10

CONCLUSION | 3 11

RECOMMENDATIONS | 4 12

REFERENCES 13

4

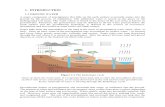

Bhutan’s Tiger Management Plan (BTMP) was established in 2005. Its

purpose is establishing actions and policies, and maintaining and

developing their current breeding tiger population. Yet Bhutan faces

many challenges. The country is developing, their population growth is

one of the highest in the world, and their people are heavily

dependent upon forest resources. Further, tiger management is

complex. It needs to account for the complex interactions that occur

within nature, society, and the economy. It needs to be adaptive;

responsive to changing political, social, and environmental landscapes.

Bhutan aspires to achieve holistic, inclusive and sustainable

development. They demonstrate a commitment to unconventional

methods of valuing development, and recognise it truly occurs when

material, emotional and spiritual well-being are balanced. These

complement and reinforce each other, promoting equitable socio-

economic development, cultural integrity, environmental sustainability

and good governance (NECS, 2012).

BTMP was developed within the context of Bhutan’s commitment to

this. Known as ‘The Middle Path’, it attempts to ensure development

doesn’t compromise cultural, traditional or environmental

sustainability (NEC, 1998). Representing one of the very few truly

indigenous systems of governance, Himalayan Buddhism provides the

context within which the policy was developed. Further, it dictates

many of the approaches taken towards policy development,

adaptation and implementation for all Bhutanese policies. Therefore,

the complexities of BTMP are enormous. Not only does it attempt to

develop a tiger management path, but it sits within this unique

development model, which sits within a unique culture. All three

recognise the importance of a holistic approach to almost everything,

and are exceedingly complex in their connectedness.

5

Tiger Management in Bhutan

BTMP has the goal of ‘maintaining a viable interconnected population

of breeding tigers in Bhutan’ that ‘exist predominately on wild prey

with minimal conflict between humans and tigers’ (Sangay &

Wangchuk, 2005, p 15). Bhutan is the only tiger range country where

conservation efforts are focused on pre-emptive and proactive

approaches to maintaining existing conditions (Sangay & Wangchuk,

2005). However, Bhutan still faces many challenges.

Almost all countries within the tigers range are developing. Success in

protecting tigers is rare. Failures have demonstrated that tiger

management needs to be adaptive; responsive to changing political,

social, and environmental landscapes; and recognise that systems are

dynamic, continually changing, adapting, and evolving.

Values within these systems are incrementally changing. This

cumulative change is difficult to recognise and respond to. Bhutan

has been one of the most successful countries in protecting the

species, but many challenges still exist.

Tigers are an apex species, sitting at the top of the food chain.

Ensuring the ecosystem is healthy and resilient is essential for tiger

survival. However, Bhutan is rapidly developing, placing pressure on

land use. Multiple stakeholders have differing views, conflicting

interests, and different ideas about the aims of sustainable

development, and how they should be achieved.

Where tigers co-inhabit with humans, livestock losses are common.

The financial loss can be large. Farmers feel they have a right to

protect their income, but the tiger also has a right to exist, and future

generations have the right to a world where the tiger exists.

6

Tiger management is not just an environmental issue. It contains elements of politics (national and

international), and requires input from many agencies with differing agendas. It cannot be ‘boxed

neatly’ into one area of responsibility and requires a holistic and inclusive approach.

It needs to consider larger geographical contexts, because tigers and issues like poaching exist in

these contexts. Trans-boundary co-operation improves and maintains habitat linkage, aids scientific

understanding and helps align outcomes. Yet local solutions are necessary. Generalisations from

elsewhere are rarely effective when transported, situations and locations are non-homogenous, and

local contexts affect local outcomes.

This occurs in a context that is time sensitive; the problem is urgent, and changes are increasingly

occurring. However, a lack of scientific information exists. Movement and behaviour patterns, and

population data, for tigers and their prey need development. This information impacts the ability to

implement adaptive management strategies and improve management plans.

Bhutan starts from an enviable place. Bhutan’s forests are intact, with a constitutional obligation to

maintain 60% forest cover. The only country in the developing world where forest cover is growing,

Bhutan starts from a position of protecting what they have, not restoring what they have lost. These

are just some of the challenges that exist in this world of multiple interactions between multiple

inputs (Harris, 2009). Uncertainty remains, change can be non-liner and not all risks are quantifiable.

7

Bhutan’s Answer to this Complexity

Bhutan practises a deep-ecologist approach to environmental

management (de Kruijf et al., 2003). The ‘Middle Path’ seeks to learn

from mistakes other countries have made on the road to

development. Bhutan’s ‘Middle Path’ embraces the Buddhist view

that enlightenment can be pursued without extremes of depravation

or self-indulgence. Non-extremism is important to nearly every

practice in every school of Buddhism; it is pragmatic and realistic

(Linthicum, 2007).

However the ‘Middle Path’ goes further. Whilst you won’t find it in

any written account, it inherently adopts Buddhist principals. These

principals require individuals to consider their view, the view of

others, and the communal view (including that of organic systems),

of how things will affect and be affected by them, as well as, how

things will affect and be affected by the eco and socio-political

systems. It further requires individuals to consider, once again from

these three viewpoints, what shapes their view and the collective

view. This demonstrates an underlying value that provides, in this

context, a unique philosophical approach to the environment,

currently unparalleled in any other eco-centric approach (Hargens,

2002). As pointed out by Hargens (2002, p 50) when relating this

principal to integral ecology,

‘This approach honours the holonic nature of the

cosmos and provides a systematic way to ensure the

myriad of contexts that give rise to environmental

issues are explored with depth and breadth’.

Adherence to this view allows individual transformation and

development to occur, in turn changing collective attitudes and

practises, and leading to new institutions supporting interior

development (Hargens, 2002). When combined with the Buddhist

view that the world is unable to be controlled, this is a framework

from which to build the ‘Middle Path’ and BTMP. It inherently deals

with complexity, aims to achieve resilience in an inclusive

environment, and accounts for uncertainty and the need to be

adaptive.

8

The Bhutanese public ‘know the problems Bhutan faces better than

anyone, they have identified the problems’ (Putnam, 2013, Para. 13).

Research indicates 78% of Bhutanese agree they are aware of the

goal of nature conservation, and 82% feel conservation goals are

properly communicated to them (Rinzin, Vermeulen & Glasbergen,

2007). This demonstrates the beginning of Bhutan’s cultural

consideration, how this can initiate public inclusion, which has the

ability to influence the way communities view projects (Joyce &

Thompson, 2000).

BTMP seeks to engage and enable communities. It highlights that

local participation and ownership is essential to the success of any

conservation effort, and that the benefits of tiger conservation

should be understood, appreciated and received by those living with

them (Sangay & Wangchuk, 2005). The unique Bhutanese culture

and the ‘Middle Path’ provide a mechanism for achieving this.

Education, iterative management, and social learning are important.

Education aims to inform the public of the importance of

conservation; iterative management attempts to deal with

uncertainty and recognises that the management of complex systems

is a learning process (Pahl-Wostl, 2004); and social learning seeks to

bring together people of different interests, norms, values and

constructions to create opportunities for new learning (Wals & Van

de Lei, 2007).

BTMP has developed education materials, prepared curriculums for

all levels of education, and seeks to fill current knowledge gaps via

research, allowing for new adaptations in management. However, it

is again the underlying cultural philosophy that provides the

mechanism to take this beyond the classroom, initiate social learning,

and develop solutions that are truly iterative.

Recently in the west, we have realised:

The lack of a complete understanding of complex-adaptive

socio-ecological systems necessitates the construction of

adaptive and resilient solutions (Walker & Salt, 2006),

Command and control regimes suffer from problems of

justice and manipulation (Considine, 1997),

Recognising differing viewpoints and constructions of reality

is essential to creating effective systems of governance (Pahl-

Wostl, 2004), and

It is impossible to place a monetary value on everything,

when we attempt this externalities present (Shiva, 1996).

9

Himalayan Buddhism inherently understands all of this. Many recent western discoveries regarding

resilience and uncertainty have existed for thousands of years in the indigenous cultures of the

Himalayas.

BTMP or the ‘Middle Path’ does not prescribe these lofty management ideals, the culture dictates

them. The management plan discusses the development of new research to aid local understanding,

it talks about the need to engage with larger geographical contexts to deal with issues of poaching

and habitat linkage, and it sees potential for conflict between different groups over land-use.

However, in other ways it has clear holes, vagueness, and you can be left wondering if this is all just

‘lip-service’. The question can be asked, how will they achieve this? A look at their development

model gives a partial but not complete understanding. Eventually you realise the answers are

exceedingly complex.

The culture inherently recognises the impossibility of achieving tiger management (or anything for

that matter) within the scope of any particular jurisdiction, department, corporation, industry,

community or lifetime. It is the ultimate in multi-disciplinary, multi-agency approaches, even going

beyond this to permeate every crevice of life and community. It is then realised that Bhutan has one

of the very few truly indigenous systems of governance, and their unique culture and development

path provide a possible avenue to truly sustainable development.

10

Problems with the Plan

In recent years, developed countries have increasingly become

involved in the sustainable development of developing countries.

Development assistance from these countries often includes

conservation programs. This can lead to the importation of

conservation paradigms and top-down environmental management

procedures (Cholchester, 2004). This transfer of regulations developed

elsewhere often fails to work, creates further problems, and can betray

the intended beneficiaries (Leach, Scoones & Stirling, 2010).

Top-down and exclusionary models of land management, associated

with the establishment of ‘National Parks’, are popular in the West

because of a lack of social interaction with these areas due to

urbanisation. The importation of these models can deny indigenous

people in the developing world their rights (Cholchester, 2004). Some

small issues present in this area within BTMP.

Bhutan’s legislative structures have been influenced by donor

countries and their policies (Rinzin, Vermeulen & Glasbergen, 2009). In

establishing these structures, top-down and prescriptive management

rules have occasionally been applied. The government has not paid as

much attention as it could have, to the traditional resource

management norms of the local people (Rinzin, Vermeulen &

Glasbergen, 2009). Occasionally, this has resulted in BTMP placing

restrictions on the use of non-timber products, problems in the

management of human-wildlife conflict, and disagreements over the

change of ownership of land (Rinzin, Vermeulen & Glasbergen, 2009).

The idea of conservation is ingrained in the Bhutanese way of life.

Conservation efforts should utilise these traditional norms rather than

try to impose new rules and regulations, depriving people of their

sense of traditional community ownership (Rinzin, Vermeulen &

Glasbergen, 2009). Fortunately Bhutanese structures have already

identified this as a problem (RGoB, 2008), demonstrating once again

that the traditional culture and ‘Middle Path’ approach provides

mechanisms for adaptation and rectifying issues when they present.

11

Bhutan has to date been successful in protecting the tiger and their

habitat. This is difficult for a developing country. Other examples of tiger

management have demonstrated that poaching offers rewards hard to

resist (Pinjarkar, 2013), and its international focus can lead to political

cover ups and denial, while tiger numbers continue to decline (Kahn,

2008).

Bhutan is determined to learn from mistakes other countries have made.

They have witnessed how single-minded pursuit of economic

development can leave a country without many of the natural, cultural,

and spiritual resources that once enriched it. Bhutan is determined to

tread a development path that excludes the extremes of depravation

and self-indulgence, and this ideal permeates every crevice of society.

This includes tiger management.

Until now they have successfully balanced economic, material,

emotional, and spiritual well-being. This has promoted equitable socio-

economic development, environmental sustainability, cultural integrity,

and good governance. Bhutan’s tigers, via BTMP, have been one of the

many beneficiaries.

However, increasing development and interaction with the global

community has a way of homogenising cultures. In Bhutan’s case this

could alter the indigenous system of governance that has allowed them

to cautiously walk a well-balanced development path. The importation

of top-down prescriptive management from donor countries

demonstrates this homogenisation. Fortunately this time, the problem

was realised.

BTMP sits within this unique indigenous development model which sits

within this unique culture. They cannot be separated and shouldn’t be.

They represent one of the most holistic tiger management approaches in

existence today. In fact, they represent one of the most holistic

approaches to country-wide, multi-agency, multi-policy governance, in

existence today. This is why many people, including those from more

eco-centric viewpoints, hold Bhutan up as a model of sustainable

development. This is why BTMP is successful.

12

Bhutan needs to continue to walk the path to, development and tiger

management, that has to date been successful. Being careful not to

directly import conservation paradigms and management policies from

donor countries, and ensuring their path is not swayed by the

enticements of development and globalisation.

Bhutan also needs to acknowledge what has worked internationally,

but assess and apply these lessons within their own unique context.

Recognising that it is their unique culture and development program

that have achieved successful tiger management, and ensuring this is

preserved.

Other tiger range countries should also acknowledge that it is Bhutan’s

unique cultural values and development model that provide a

mechanism for successful environmental sustainability and tiger

management. The holistic nature of this allows for social learning and

adaptation. Tiger range countries should examine how they can better

integrate the issues of the economy, society, and the environment, to

achieve more holistic management.

It is very rare to find an environmental management regime that

successfully achieves its aims. If other countries are to succeed in

protecting the environment, they need to learn from Bhutan that it

cannot be achieved by a management plan alone.

13

#Abakerli, S. (2001). A critique of development and conservation policies in environmentally

sensitive region in Brazil. Geoforum, 32, 551-565.

#Cholchester, M. (2004). ‘Conservation policy and indigenous peoples’. Environmental Science and

Policy, 7, 145-153.

*Considine, M. (1997). The corporate management framework as administrative science: A critique.

In Considine, M. & Painter, M. (Eds) Managerialism: The Great Debate. Melbourne University Press:

Melbourne.

*de Kruijf, H., van Ierland, E., Van Der Heide, C.M. & Dekker, J. (2003). Attitudes and their influence

on nature valuation and biodiversity management in relation to sustainable development. 127-44. In

Rapport, D., Lasley, W. & Rolston, D. (Eds) Managing for healthy ecosystems. Lewis Publishers, Boca

Raton.

Hargens, S.B.F. (2002). Integral Development: Taking 'The Middle Path' Towards Gross National

Happiness. Journal of Bhutan Studies, Vol. 6, pp 24-87.

*Harris, G. (2009). Thinking sustainability within complex regional NRM systems. Eds: B. Ostendorf, P.

Baldock, D. Bruce, M. Burdett, P. Corcoran, Proceedings of the Surveying & Spatial Sciences Institute

Biennial International Conference, Adelaide 2009 (2009), pp. 1001-1014.

*Hendriks, C.M. (2010). Inclusive governance for sustainability. 150-60. In Brown, V.A., Harris, J.A. &

Russell, J.Y. (Eds) Tackling wicked problems through the transdisciplinary imagination. Earthscan,

London and Washington D.C.

*Joyce, S. & Thompson, I. (2000). Earning a social licence to operate: Social acceptability and

resource development in Latin America. The Canadian Mining and Metallurgical Bulletin, 93, 1037.

Kahn, J. (2008, May 5). ‘India’s Missing Tigers’. Newsweek, 151(18), Retrieved November 29, 2013

from http://bigcatrescue.org/indias-missing-tigers/

*Leach, M., Scoones, I. & Stirling, A. (2010). Sustainability Challenges in a Dynamic World. In

Dynamic sustainabilities: Technology, environment, social- justice, chapter 1, 1-13. Earthscan.

London, UK

Linthicum, K. (2007). Changing Channels: The Bhutanese Middle Path Approach to Television.

Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. Paper 211. Retrieved from

http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/211

14

National Environment Commission (NEC) (1998). The Middle Path: National Environment Strategy for

Bhutan. Royal Government of Bhutan, Thimphu, Bhutan

National Environment Commission Secretariat (NECS) (2012). Bhutan: In Pursuit of Sustainable

Development. National report for the United Nations conference on sustainable development 2012.

Royal Government of Bhutan, Thimphu, Bhutan.

*Pahl-Wostl, C. (2004), Complexity and integrated resources management. In Pahl-Wostl, C.,

Schmidt, S. and Jakeman, T. (eds) iEMSs 2004 International Congress: International Environmental

Modelling and Software Society, Osnabrück, Germany, June 2004.

Pinjarkar, V. (2013, September 13). ‘More than 20 Tigers Poached, Says Arrested Trader Sarju’. Times

of India. Retrieved November 29, 2013 from

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/flora-fauna/More-than-20-tigers-poached-

says-arrested-trader-Sarju/articleshow/22550019.cms

Putnam, A. (2012, October 8). ‘Bhutan’s middle path’. The New York Times. Retrieved from

http://scientistatwork.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/08/bhutans-middle-path/

#Rinzin, C., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Glasbergen, P. (2007). Public perceptions of Bhutan’s approach to

sustainable development in practice. Sustainable Development, 15(1), 52-68.

#Rinzin, C., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Glasbergen, P. (2009). Nature Conservation and Human Well-

Being in Bhutan: An Assessment of Local Community Perceptions. Journal of Environment &

Development, 18(2), 177-202.

Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB) (2008). Report on the International Workshop on Forests,

Landscape, and Governance: The Roles of Local Communities, Development Projects, the State, and

Other Stakeholders. A Co-operative venture between the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment

and Bhutan’s Social Forestry Division of the Department of Forestry. Workshop September 3-8, 2008,

Punakha, Bhutan.

Sangay, T. & Wangchuk, T. (2005). Tiger Action Plan for the Kingdom of Bhutan 2006-2015. Nature

Conservation Division, Department of Forests, Ministry of Agriculture, Royal Government of Bhutan,

Thimphu, Bhutan. ISBN 99936-666-0-2

#Sekhar, N.U. (2003). Local people’s attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around

Sariska Tiger Reserve. India. Journal of Environmental Management, 69, 339-347.

*Shiva, V. (1996). Values beyond price. www.unep.org, retrieved July 28, 2010 from

http://www.unep.org/OurPlanet/imgversn/82/shiva.html.

*Wals, A. & van der Leij, T. (2007). Introduction. 17-32. In Wals, A. (Ed.) Social learning towards a

sustainable world: Principles, perspectives, praxis. Wageningen Academic, Wageningen.

*Walker, B. & Salt, D. (2006). Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing

world. Island Press, Washington, D.C.