Speaking Phrases Boricua: Puerto Rican Sayings (Book Preview)

879-PUERTO RICAN AM - AmericansAll

Transcript of 879-PUERTO RICAN AM - AmericansAll

PUERTO RICANS:IMMIGRANTS AND MIGRANTS

A Historical Perspective

Clara E. RodríguezIntroduction by Joseph MonserratPhotographs Compiled by Michael Lappand Gilbert Marzán

Americans All®

Copyright © 1991, 1993 and 2000, by the People ofAmerica Foundation. This publication has been suppliedto the participating school or school system for use in theAmericans All® program. All rights reserved. AmericansAll® authorizes the educational institution to reproduceany portion of this publication for use in its instructionalprogram provided proper credit is given to AmericansAll®. Commercial use or reproduction of any of thismaterial in any form requires the written permission ofthe People of America Foundation.

ISBN 1-56192-000-2

Library of Congress 91-091028, No. 6

Printed and bound in the United States of America

PUERTO RICANS:IMMIGRANTS AND MIGRANTS

A Historical Perspective

Clara E. RodríguezIntroduction by Joseph Monserrat

Photographs Compiled by Michael Lappand Gilbert Marzán

Americans All®

Editorial and Advisory StaffMichael Lapp, Ph.D., has taught United States history

at the City College of New York. His thesis at JohnsHopkins University dealt with Puerto Rican migration tothe United States mainland in the 1940s and 1950s, andhe has conducted extensive archival research on PuertoRican migration history.

Gilbert Marzán is a senior at the College of StatenIsland, City University of NewYork. He is currently pur-suing a bachelor’s degree in sociology/anthropology.

Joseph Monserrat, former national director of theMigration Division of the Puerto Rican Department ofLabor, has lectured extensively on education, labor,migration, farmworkers and minority group problems.He has taught at the college level and has served as pres-ident of the New York City Board of Education. Activeon many community and civic boards, he is currentlyworking on a book tentatively titled Hispanic, USA.

Clara E. Rodríguez, Ph.D., is an associate professor inthe Division of Social Sciences at Fordham University’sCollege at Lincoln Center, NewYork. Previously she wasthe dean of Fordham University’s School of GeneralStudies. Currently on sabbatical, she is a visiting scholarat the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and therecipient of grants from the Inter-University Program/Social Science Research Council, the RockefellerFoundation and the Business and Professional Women’sAssociation. She is the author of Puerto Ricans, Born inthe U.S.A., as well as numerous articles focusing on thePuerto Rican community in the United States.

Note: Biographical information was compiled at the time the indi-viduals contributed to Americans All®.

Organizational ResourcesCentro de Estudios Avanzados de

Puerto Rico y el CaribeP.O. Box 9023970San Juan de Puerto Rico 00902-3970(787) 723-4481 / 723-8772e-mail: [email protected]

Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueñosc/o Hunter College695 Park AvenueNewYork, NY 10021(212) 772-5689

Department of Puerto Rican CommunityAffairs in the United States

3 Park Avenue, 33rd FloorNewYork, NY 10016(212) 252-7300

El Museo del Barrio1230 5th AvenueNewYork, NY 10029(212) 831-7272

Fundacíon Puertorriqueña de las HumanidadesP.O. Box 9023920San Juan de Puerto Rico 00902-3920(787) 721-2087e-mail: [email protected]

Institute of Puerto Rican CultureEl Instituto de Cultura PuertorriqueñaP.O. Box 9024184San Juan de Puerto Rico 00902-4184(787) 723-2115

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund99 Hudson Street, 14th FloorNewYork, NY 10013(212) 219-3360, ext. 246 Fax: (212) 431-4276

University of Puerto RicoLibrary and Museum of Art, History and AnthropologyP.O. UPR 21908San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931-1098(787) 764-0000 Fax: (787) 763-4799

Contents

Page

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iv

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v

Puerto Ricans: Immigrants and Migrants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

A Mining and Trade Center . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Nineteenth-Century Immigration Boom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Unique Position on Slavery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

The United States Takes Over Puerto Rico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Economic Dependence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Migration Patterns and Communities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Operation Bootstrap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Migration to the States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

The Migrants. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Contract Laborers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Class and Selectivity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Differences between Puerto Rican Migrants and European Immigrants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Colonial (Im)migrants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Migration Statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

The Job Market’s Influence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

The Department . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Puerto Ricans in the United States, 1980 (map) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

States with Major Puerto Rican Populations, 1980, 1970 and 1960 (table). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Student Background Essays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

The Photograph Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Bibliography. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Photo Credits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Front Cover . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Back Cover . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

The Photograph Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Maps of Puerto Rico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Back Cover

Today’s youth are living in an unprecedented period ofchange. The complexities of the era include shifts indemographics, in social values and family structures aswell as in economic and political realities. A key to under-standing young people’s place in both the present and thefuture lies in history. History is so much more than a col-lection of facts.When appropriately studied, it is a lens forviewing the motivations, beliefs, principles and impera-tives that give rise to the institutions and practices of peo-ple and their nations. As our nation’s schools reform theircurricula to reflect the diversity of our school-age popula-tion, a major challenge arises. Is it possible to teachUnited States history as a history of diversity withoutevoking feelings of anger, bitterness and ethnic hatred?Is it possible to diversify classroom resources withoutgenerating feelings of separatism and alienation?

AmericansAll® answers “yes” to both these questions.The Americans All® program has proven that not only isit possible, it is preferable. By choosing to chronicle thehistory of six diverse groups—Native Americans,African Americans, Asian Americans, EuropeanAmericans, Mexican Americans and Puerto RicanAmericans—the program provides a frame upon whichan inclusive approach to education on a nationwide basiscan be built.

Nomenclature, regional differences, language and thedemands of interest groups will always challenge anevolving diversity-based approach to education. Thesechallenges are by-products of the freedoms that we trea-sure and strive to protect. This reality necessitates a pro-cess that becomes part of the product, however.Americans All® has integrated feedback from a diversegroup of scholars in developing this program and main-tains open lines of communication for continuous inputfrom educators, parents and community members. Theprogram’s emphasis on six groups is based on historicpatterns of migration and immigration. These six groupsprovide an umbrella under which many other groups fall.By developing 51 customized, state-specific resourcepackages, the continuing saga of diversity in the UnitedStates can and will be told.

Americans All® has succeeded in avoiding the landmines found in victim/oppressor approaches to ourdiverse history by using a thematic approach. The themefocuses on how individuals and families immigrated toand migrated through the United States (voluntarily andby force). Carefully planned learning activities engageteachers and students in comparative critical thinking

about all groups simultaneously. These activities ensuresensitivity to the previously untold stories of women,working-class people and minority and majority groups.Results from the program’s implementation in ethnicallyand culturally diverse school systems confirm the efficacyof this approach.

We have answered “yes” to the frightening questionsabout teaching diversity without teaching hate. Ournation’s leaders must now answer even more frighteningquestions: Can we afford not to teach history that isdiverse and inclusive when school dropout rates rangefrom 25 percent to 77 percent among Native American,AfricanAmerican,AsianAmerican, Hispanic and foreign-born youth? Can we afford to continue preparing somany of our nation’s youth for a future of exclusion fromthe economic mainstream—a future that mirrors a historycurriculum that excludes them?

To compound the problem, we must add the very realconstraint of urgency. The future of our nation is char-acterized by computer technology and global interde-pendence. All students, regardless of their gender ortheir socioeconomic, ethnic or cultural status, must behelped to see themselves as participants in this humancontinuum of scientific and mathematical developmentto both visualize and actualize a place for themselves inour future.

Students need to be challenged to think critically andexamine how today’s technology grew out of yesterday’sindustrial era, an era spawned by the agricultural accom-plishments of prior generations. They need to understandthat even the simple tasks of weaving fabric and makingdyes from fruits or plants required mathematical and sci-entific understanding; that today’s freeways grew out ofyesterday’s hand-hewn trails; that ancient tribal herbsfrom many cultures formed the basis of many of today’swonder drugs; and that it took the agricultural skills ofmany different peoples to produce the nucleus of today’scomplex farming and food industries. Students must alsosee the relationship between citizenship responsibilitiesand privileges and understand their own importance inthat dynamic.

The Americans All® materials provide diverse andinclusive images of history that can be a catalyst for thistype of understanding. Not only is it wise to teach aboutdiversity, using an inclusive approach as modeled in theAmericans All® program, it is essential.

Gail C. ChristopherJanuary 1992

iv

Preface

Professor Clara Rodríguez clearly and conciselypresents a historical perspective of Puerto Rico andof the Puerto Rican migration to the United States.Dr. Rodríguez’s study illustrates that although legallymigrants—meaning citizens migrating within the bor-ders of their own country—upon arrival these migratingcitizens are seen and treated as immigrants, as foreignersin their own land. Her presentation provides a timelyintroduction to the next chapter in the developing story ofUnited States–Puerto Rico relations.

Puerto Rico, ceded to the United States by Spain in1898, has been an unincorporated territory of the UnitedStates since 1900, and Puerto Ricans have beenAmerican citizens since 1917. After almost a century,Puerto Ricans finally will determine for themselves whattheir permanent relationship to the United States will be.Congress is in the process of developing legislation thatwould authorize a referendum in which Puerto Ricanswould choose among statehood, independence, com-monwealth in a new form or none of the above as thefinal solution to their political status.

From all previous voter indications, Puerto Rico andPuerto Ricans will remain a permanent part of the nation.The issue yet to be determined in the referendum iswhether the island will become the fifty-first state or will

continue in permanent association with the United Statesas a commonwealth but in a new and enhanced form. Ineither case Puerto Ricans would remain citizens andPuerto Rico would form a permanent part of theAmerican union. In previous elections fewer than 10 per-cent of Puerto Rico’s voters have voted in favor of theisland becoming an independent republic.

By culture, language and history—and despite classand racial diversity—Puerto Ricans are a single people,as are Germans, Italians and the members of the manydifferent Native American nations. Yet even as a singlepeople, the reality of those Puerto Ricans living on theisland is different from the reality of their cousins livingin the United States. On the island they are “the people”—the majority. In the United States they are often relegatedto the status of a “nonwhite minority group.”

The absence in Puerto Rico of the concept of “minor-ity groups” and of discrimination based on color as theseexist in the continental United States represents the singlemajor difference between the reality of island PuertoRicans and their brothers and sisters who live in theUnited States.Although color and class issues exist on theisland, in this regard and in other areas of humanrelations, Puerto Ricans have much to teach theirfellow Americans.

Joseph MonserratSeptember 1990

v

Introduction

The population grew from 70,250 in 1775 to 330,051 in1832. From 1775 to the end of the nineteenth century,it multiplied more than 13 times.

As the population grew it became more and morediverse. Although most of the nineteenth-century immi-grants probably came from Spain and its possessions, agreat many came from other European countries.Common present-day Puerto Rican surnames, for exam-ple, Colberg, Wiscovitch, Petrovich, Franqui, Adams andSolivan, reflect that diversity.

Unique Position on SlaveryBoth legally owned enslaved Africans and runaway

slaves continued to arrive until 1873, when slavery wasofficially abolished. Runaway slaves from other countrieshad been admitted to Puerto Rico as free and allowed toearn a wage since 1750. By the time Puerto Rico bannedslavery, free Africans outnumbered enslaved ones.

Puerto Rico’s situation with regard to slavery and racerelations was unusual. As Eric Williams, distinguishedhistorian and specialist in West Indian politics, pointsout, “The Puerto Rico situation was unique in theCaribbean, in that not only did the white population out-number the people of color, but the slaves constituted aninfinitesimal part of the total population and free laborpredominated during the regime of slavery.” Puerto Ricodid not have the same need for slave labor that islandswith large plantation economies did. Because it had asmall-farm and diversified economy, Spain may haveseen it as a less wealthy colony than others. Williamssays if “Puerto Rico, by the conventional standards of thefinal quarter of the nineteenth century, ranked as one ofthe most backward sectors of the Caribbean economy, inintellectual perspective it was head and shoulders aboveits neighbors.” (Williams, 1970) Puerto Rican leaders

Puerto Rico, an island in the Caribbean, has a long andrich history. Christopher Columbus landed on the islandin 1493 during his second voyage to America. The Tainopeople who lived there called the island “Borinquen.”Today Boricua means Puerto Rican, and many PuertoRicans refer to the island as Borinquen in verses, songsor conversations.

A Mining and Trade CenterAfter the arrival of Spanish explorers, Puerto Rico,

which means “rich port,” became a mining center forgold and silver. Soon the metals died out, as did the TainoIndians who had worked in the mines.

Interested in retaining the island as a strategic base,Spain encouraged the colonists to grow crops and for-bade anyone, under penalty of death, to leave the islandfor the newly discovered gold and silver mines in Mexicoand Peru.

In the seventeenth century, Puerto Rico developed agrowing trade in livestock, hides, linen, spices andenslaved people, both African and Native American.Because of Spain’s restrictions on trade, however, muchof it was contraband.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Spain haddecided to liberalize its policies in the colonies withregard to trade, immigration and political rights. Havingsuffered serious defeats by English forces and a depletedtreasury, Spain turned to colonial trade as a way ofreplenishing and improving its economic position.

Nineteenth-CenturyImmigration Boom

By the nineteenth century, Puerto Rico had become abustling trade center and host to thousands of immigrants.

1

Puerto Ricans: Immigrants and MigrantsClara E. Rodríguez

“We proceeded along the coast the greater part of that day, and on theevening of the next we discovered another island called Borinquen . . . .

All the islands are very beautiful and possess a most luxuriant soil,but this last island appeared to exceed all others in beauty.”

Translated from a letter written on November 19, 1493,by Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca, who accompanied

Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to America.

argued in Spain for the economic superiority of freelaborers over enslaved laborers. This position distin-guished it from other colonial possessions.

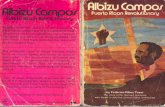

In the nineteenth century, Puerto Rican political develop-ment blossomed. By the end of the century, it appears thatresidents had a strong sense of national identity. This basicunity existed despite obvious political frictions and classdivisions. Thus, by the time that the Spanish-American Warbegan in 1898, Puerto Rico had evolved strong politicalideals of independence and autonomy and had succeeded—in 1897, after 400 years of Spanish colonial rule—in gaininga Charter ofAutonomy from the Spanish government.

Reflecting on the history of Puerto Rico prior to theUnited States’war with Spain, we see a long and rich his-tory. It is interesting to note, for example, that PuertoRico’s coat of arms dates back to 1511, more than a cen-tury before the Pilgrims arrived in North America. Also,by the time the United States acquired Puerto Rico in theSpanish-American War, Puerto Rico was already olderthan the United States is today. It had a university whosedegrees were recognized in Spain and flourishing musi-cal, literary and cultural traditions.

The United States Takes OverPuerto Rico

When the United States invaded the island in 1898,some Puerto Rican independentistas (independenceadvocates) in Puerto Rico and in New York’s vigorousand well-established Puerto Rican community assistedthe United States because they expected it to help liber-ate Puerto Rico from Spain. The independentistas wereextremely disappointed and disillusioned when it becameclear that the United States would not grant the islandgreater autonomy or independence.

Indeed, as a commonwealth under the American gov-ernment, Puerto Rico had less political and economicautonomy than under Spain’s Charter of Autonomy. Thecharter had given Puerto Rico rights: to elect voting rep-resentatives to the Spanish Congress; to participate innegotiations between Spain and other countries affectingthe commerce of the island and ratify or reject commer-cial treaties affecting Puerto Rico; and to frame tariffsand fix customs on imports and exports. These rightswere not retained under the American flag.

In many regards, the charter granted greater autonomythan Puerto Rico currently enjoys under the Americangovernment. At present Puerto Rico is represented in theUnited States Congress only by a resident commissionerwho cannot vote. Residents of Puerto Rico cannot vote ineither presidential or congressional elections. The presi-dent and Congress have, nonetheless, sent Puerto Ricanmen to fight in American wars. In addition, Puerto Rico

today does not have as much control over its commerceas it did under the charter.

Economic DependenceThe United States’ occupation made Puerto Rico both

politically and economically dependent. The PuertoRican economy experienced dramatic changes after theAmerican takeover. The economy went from a diversi-fied, subsistence economy with four basic crops pro-duced for export (tobacco, cattle, coffee and sugar) to asugarcane economy with 60 percent of the sugar industrycontrolled by absentee American owners. In the 1920sthe decline of the cane-based industry, combined with noreinvestment and continued population growth, resultedin high unemployment, poverty and desperate conditionsin Puerto Rico. These factors propelled the first waves ofPuerto Ricans to the United States in the twentieth cen-tury. The 1930s saw more migration as workers sought todeal with the island’s stagnant economy.

In the 1940s World War II boosted the flagging econ-omy somewhat. The Puerto Rican government initiatedreforms and entered into what has been variously calledits “state capitalist development phase” and its “socialist”venture. The Puerto Rican Development Corporationestablished and ran government-owned enterprises, includ-ing glass, pulp and paper, shoe leather and clay productscorporations. The government financed but did notoperate a hotel and a textile mill. Influenced by theNew Deal philosophy, this program stressed both socialjustice and economic growth goals. It was, in theseregards, ahead of its time. Had this program succeeded,the island would have achieved greater economic inde-pendence. However, these efforts were frustrated by tech-nical problems and opposition from local and nationalgovernment officials and business interests. (Dietz, 1986)

Migration Patterns andCommunities

Puerto Ricans, and even Puerto Rican organizations,have been in New York City since the nineteenth century.It was only after 1900, however, that significant numbersof Puerto Ricans came, and the bulk of the migrationoccurred in the 1950s and 1960s (see the graph on page 3,“Migration from Puerto Rico, 1920–1986”). The migra-tion of Puerto Ricans after theAmerican takeover has beenclassified into three major periods. During the first period,1900–1945, the pioneers arrived. Most of these pionerosestablished themselves in New York City in the AtlanticStreet area of Brooklyn,El Barrio in East Harlem and suchother sections of Manhattan as the Lower East Side, theUpper West Side, Chelsea and the Lincoln Center area.

2

alization thrust and its clear incorporation into an emerg-ing global economy.

During this period Puerto Rico improved in many areas(e.g., education, housing, drinking water, electrification,sewage systems, roads and transportation facilities).Residents of Puerto Rico felt a clear and present sense ofdevelopment and progress and, for some, a more equi-table income distribution.

The industry that was attracted, however, did not pro-vide sufficient jobs. With increased population growthand displacement from traditional labor pursuits, thegrowing population could not be accommodated. Muchof the surplus labor migrated to the United States.

Migration to the StatesThe question of what prompted the migration of Puerto

Ricans to the United States has numerous answers. Earlytheorists said overpopulation, brought about by improvedmedical care in Puerto Rico, was themajor factor. Recently,researchers have tended to see migration as a response ofsurplus labor to economic changes that yielded increas-ingly larger numbers of displaced and surplus workers.

Micro-level analyses found economic push-and-pull fac-tors relevant. When national income went up and unem-ployment went down in the United States, Puerto Ricanmigration increased. Relative wages and unemploymentrates in Puerto Rico and the United States also affectedmigration to the United States and back to Puerto Rico.Therefore, Puerto Ricans, like many others, migrated whenjob opportunities looked better in the United States andworse in Puerto Rico. (Research has shown that PuertoRicans did notmigrate to secure better welfare benefits.)

Some writers have emphasized the role of Americancompanies in recruiting Puerto Rican labor to work in theUnited States. Still others cite the role of government.Although the official position of the Puerto Rican gov-ernment was that it did not encourage or discouragemigration, some argue that the Puerto Rican governmentasked the Federal Aviation Administration to approvelow rates for air transportation between Puerto Rico andthe United States and asked that the Migration DivisionOffice in NewYork facilitate migration. (Padilla, 1987)

Migration was undoubtedly caused by a combinationof these and other factors. For example, the conferringof citizenship status in 1917 and the 1921 legislationrestricting immigration directly and indirectly inducedPuerto Ricans to migrate.

After World War II, era-specific factors may have con-tributed to the migration (e.g., greater participation in theArmed Forces; pent-up travel demand; surplus aircraft andpilots, making air travel less expensive and more accessi-ble; and greater opportunities in the United States).

Some began to populate sections of the South Bronx.During this period contract industrial and agriculturallabor also arrived, providing the base for many of thePuerto Rican communities outside NewYork City.

The second phase, 1946–1964, is known as the “GreatMigration.” During this period the already-establishedPuerto Rican communities of East Harlem, the SouthBronx and the Lower East Side increased their numbersand expanded their borders. Communities in new areas ofNew York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois and otherparts of the country appeared and grew, but the bulk of thePuerto Rican population continued to reside in NewYork.

The last period, “the revolving-door migration,” datesfrom 1965 to the present and involves a fluctuating pat-tern of net migration as well as greater dispersion to otherparts of the United States. As the following graph,“Migration from Puerto Rico, 1920–1986,” illustrates,the last few years have shown net outflows from PuertoRico that begin to rival those experienced in the early1950s. By 1980 most Puerto Ricans in the United Stateswere living outside NewYork State. Today Puerto Ricanslive in every state, with the largest numbers beingconcentrated in northeastern cities.

Operation BootstrapBetween 1947 and 1951 government development of

industry gave way to promotion of private investment. Thenew approach was called “Operation Bootstrap.” A fore-runner of the economic development strategies imple-mented throughout the world later, the idea was toindustrialize the island by luring foreign, mainlyAmerican, companies to Puerto Rico with the promise oflow wages and tax incentives. The tourism industry wasalso developed at this time. Puerto Rico began its industri-

3

Migration from Puerto Rico, 1920–1986

80,00060,00040,00020,000

0-20,000-40,000

Year_______________Sources: 1920–1940 data: United States Commission on Civil Rights.

1940–1986 data: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico,Negociado de Análisis Económico.

1920

1927

1934

1941

1948

1955

1962

1969

1976

1983

1986

Migrants

Yet perhaps what has been most important in pro-pelling Puerto Rican migration is what has been least vis-ible to the migrants. This is the political and economicrelationship between Puerto Rico and the United States.If not for this tie, American tax breaks would not havebeen granted to American firms doing business in PuertoRico; duty-free export and import would not have beenallowed between Puerto Rico and the United States; cap-ital could not have flowed without controls; andAmerican factories and American management wouldnot have gone in such numbers. The influx of Americancompanies, products and culture made Puerto Ricansfamiliar with life in the United States. This practicalknowledge of, and exposure to, features of American lifemay well have stimulated immigration.

In addition, without this relationship, increases innational income or employment in the United Stateswould not have provoked emigration as quickly fromPuerto Rico. There would not have been open borders, amilitary experience for Puerto Rican men and women,citizenship status, accessible and frequent air travel, earlycommunications and education systems tied to thecolonial center. These factors helped fan the migration.

Although economic push factors spurred the decisionto migrate, it is also likely that many Puerto Ricans werepulled by the promise (or hope) of a better life, a lifelike the one they perceived Americans to have, a life towhich they, as American citizens, were also entitled.Undoubtedly they also were pulled by connections tofamily already in the United States. These connectionsexpanded into self-reinforcing networks. Finally, Puerto

Ricans were pulled by an adventurous perspective—onethat proposed they try their luck in a new land, that theystrive for something better.

The MigrantsPuerto Rican migrants had diverse backgrounds. Many

came from the campos (rural areas) where the farminghad become economically marginal; these migrantswere, essentially, displaced farmers and farm laborers.They migrated directly to New York City, to other largecities or to small towns and farming communities. Manywho first worked as agricultural laborers later moved tomore urban areas.

Others came from Puerto Rico’s pueblos (towns). Formany of these the trek to the United States was a secondmigration; they were often one generation or lessremoved from the campos. Underemployed or unem-ployed, they followed the same paths as those from thecampos. After 1965 those who arrived were generallyalready highly urbanized.

Usually the facts and statistics on occupations fail toreveal the immigrants’ diversity and richness. Peasantsand urban workers alike included sugarcane cutters andcommon laborers. Yet among those searching for a betterlife were also accomplished musicians, fine needlecraftworkers, country doctors and midwives, entrepreneurs,botanists, spiritualists, practical agronomists, skilled arti-sans (in wood, cement and leather), artists and able polit-ical workers.

The migrants seldom used these skills to earn a livingin the United States, so these skills went unnoticed inmany cases. As Oscar Handlin points out, as newcomers“they had to accept whatever jobs were available. Eventhose who arrived with skills or had training in white-collar occupations had to take whatever places wereoffered to them.” (Handlin, 1959) Many schoolteachersbecame factory workers, cab drivers and restaurant work-ers. Thus, although some statistical measures may reflecta fairly uniform class structure, the measures do not ade-quately account for nontransferable skills and the down-ward mobility initially experienced by many migrants.The Puerto Rican population is a heterogeneous one thatreflects the distinct classes found on the island, plus thedevelopment of new class positions and perspectives inthe United States.

Contract LaborersContract laborers were one stream in the Puerto Rican

migration. Many returned to Puerto Rico after complet-ing their contracts, and others moved quickly out of agri-cultural contract labor and established homes in urban

4

Puerto Ricans, like many others, migrated when opportunitiesin the United States looked better than those at home.

settings. Initially recruited by companies and then by“the family intelligence service,” these migrants formedthe nucleus of Puerto Rican communities that would sub-sequently develop in less urban areas or outside the NewYork metropolitan area, such as in Hawaii, California,Arizona and other southwestern states. Communities inLorain, Cleveland and Youngstown, Ohio, and in Gary,Indiana, began this way.

Contract labor migration began soon after 1898 and hascontinued to the present. Indeed, the very first group tomigrate to the United States after the Spanish-AmericanWar was made up of contract laborers who went to Hawaii.For many, the farm labor system was the first step towardresidence in the United States, usually in urban areas.

Class and SelectivityThe class composition of the Puerto Rican communi-

ties has changed over time, but the communities havealways retained a distinctive diversity. We know that thenineteenth-century Puerto Rican community was madeup of generally well-to-do merchants, political activistsclosely allied with the Cuban revolutionary movementand skilled workers, many of whom were tabaquereos(skilled tobacco workers). By the first quarter of thetwentieth century, the Puerto Rican community, a numberof scholars say, consisted of people in predominantlyworking-class occupations. In the post-World War IIperiod of heavy immigration, the composition of thesecommunities continued to reflect diversity but with astrong working-class base.

Differences between PuertoRican Migrants and EuropeanImmigrants

Although Puerto Rico and the United States came to bejoined through an act of conquest, Puerto Ricans tendedto be seen as part of the continuum of immigrant groupsto the United States. Puerto Ricans were—and, to a largeextent, still are—like other immigrants in that they wereforeign in culture, language and experience. Yet PuertoRicans differed from European immigrants in significantways. Puerto Ricans entered the United States as citizens,served in the Armed Forces, could travel back and forthacross an open border and had a Caribbean cultural andracial background.

Colonial (Im)migrantsPuerto Ricans are migrants because they come as United

States citizens, but they are also immigrants because theyarrive with a different culture and language. Given the his-torical and present-day significance of the political and eco-nomic relationship between the United States and PuertoRico, Puerto Ricans may be more similar to other colonialimmigrants—for example, Algerians, Tunisians, Moroc-cans and West or East Indians immigrating to English,French and Dutch “fatherlands” during the past twodecades—than to European immigrants to the UnitedStates. These former or present colonial immigrants havemigrated to the colonial center after World War II for rea-sons similar to those that drove the Puerto Rican migration.

5

Immigrants from Puerto Rico were diverse, including accomplished musicians searching for a better life.

The United States is a land of newcomers, with peoplemoving both from within and outside the nation’s bor-ders. Each year millions of Americans cross county orstate lines, changing their place of residence in search ofeducational opportunities and better working and livingconditions. They include American citizens from thecommonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Puerto Ricans come to the United States to work. Theygained citizenship by birthright in 1917. In recentdecades these Spanish-speaking American citizens havefilled labor shortages in many important mainlandindustries—the textile and garment industries of NewYork, the electronics industries in Illinois, the foundriesin Wisconsin, the steel mills in Ohio, Indiana andPennsylvania and farms in the East and Midwest.

The Job Market’s InfluenceToday Puerto Ricans live in every state. Their migra-

tion to the mainland has fluctuated in accord with the jobmarket. During the 1950s, when mainland jobs were rel-atively plentiful, an average of 45,000 Puerto Ricans leftthe island each year to live in the United States. Duringthe 1960s Puerto Rico’s Operation Bootstrap industrial-ization program created enough new factory jobs toabsorb many of the unemployed, and migration to themainland decreased to an average of 20,000 per year.

During the first half of the 1970s, the economic reces-sion in the United States sharply reduced job opportuni-ties. Because of this, Puerto Rican migration to themainland actually reversed itself; more people returnedto the island than migrated to the United States.

In addition to Puerto Ricans living on the mainland,several thousand migratory workers come each springand summer to fill farm labor shortages in many statesalong the eastern seaboard and in the Midwest. Most ofthese workers return to Puerto Rico at the end of the farmseason. The slack season in sugarcane (the winter crop inPuerto Rico) coincides with the peak farm season in theUnited States, so this arrangement enables mainlandfarmers to obtain much-needed labor and Puerto Ricanagricultural workers to obtain work.

The DepartmentThe Department of Puerto Rican CommunityAffairs in

the United States was created according to Public Law101-58 August 16, 1989. The department’ mission is totake joint action with the Puerto Rican community in theUnited States, for the purpose of making the rights of thiscommunity valued and respected, and to strengthen themechanisms that will permit the community to secure foritself the means necessary to live a dignified life.

Services ProvidedThe Political Orientation and Action Program

(ATREVETE) coordinates voter registration drives aswell as offers information on voters’ rights, informationon the use of the voting machine and general informationon elections and other electoral processes.

The Social Services Program provides information oneducational opportunities and educational issues in theUnited States and in Puerto Rico. Orientation and refer-ral services on employment opportunities are providedalong with occupational counseling. This program alsomaintains information on social services programsthroughout the United States and in Puerto Rico.Assistance and referrals to social services programs and

6

The Puerto Rican Department of Labor helps workers leav-ing the country find jobs in the United States.

Migration StatisticsDepartment of Puerto Rican

Community Affairs in the United States

agencies are available. Technical assistance and advice topublic and private agencies that work with Puerto Ricanscan be obtained. Individuals can also gain assistance withsecuring vital documents, such as birth, marriage,divorce and baptismal certificates, from Puerto Rico.Advice and assistance is provided on the procedures forlegitimizing natural children, name changes and belatedbirth registrations, as well as identification cards forPuerto Ricans born on the island.

The Cultural Promotion Program promotes the culturalactivities and events of the Puerto Rican communitythroughout the United States and fosters cultural contactand interchange with the island.

The Legal Assistance Program provides legal assis-tance and/or referral in all situations that have a signifi-

cant impact on the rights of Puerto Rican people residingin the United States.

The Migrant Farm Workers Program, in coordinationwith the Department of Labor of Puerto Rico, provides ser-vices and protects the rights of Puerto Rican farmworkerswho have come to work on North American farms.

In addition to the programs described above, thedepartment also plans to introduce a comprehensivehuman resources program, which will collaborate withnational and local organizations to promote occupationaland professional development that will enable PuertoRicans to compete in the job market.Another project willbe directed to individuals and community groupsinterested in developing and promoting small businessenterprises.

7

W

W

1

V

V

T

Was

hing

ton

5,06

5

Ore

gon

1,76

8Id

aho

407

Mon

tana

293

yom

ing

287

Nor

thD

akot

a24

7

Sout

hD

akot

a23

1

Min

neso

ta1,

550

isco

nsin

10,4

83

Iow

a70

9

Mic

higa

n12

,425

Illin

ois

129,

165

Indi

ana

2,68

3

Ohi

o32

,442

Penn

sylv

ania

91,8

02

New

York

986,

802

Mai

ne71

4 Mas

sach

uset

ts76

,450

New

Ham

pshi

re1,

316

erm

ont

324

Rho

deIs

land

4,62

1C

onne

ctic

ut88

,361

New

Jers

ey24

3,54

0

Del

awar

e4,

801

Mar

ylan

d9,

014

Dis

trict

ofC

olum

bia

1,43

0

Wes

tV

A66

2K

entu

cky

2,74

7

irgin

ia10

,227

Nor

thC

arol

ina

7,42

0So

uth

Car

olin

a4,

114

Tenn

esse

2,39

9

Geo

rgia

7,88

7

Flor

ida

94,7

75

Loui

sian

a4,

539

Mis

siss

ippi

1,05

8

Ala

bam

a2,

299

Ark

ansa

s82

8O

klah

oma

2,87

3

Mis

sour

i2,

512

Kan

sas

2,97

8

Neb

rask

a62

7

exas

22,9

38

New

Mex

ico

1,61

0

Ariz

ona

4,04

8

Cal

iforn

ia93

,038

Nev

ada

1,85

3U

tah

1,49

4C

olor

ado

4,24

6

Ala

ska

965

Haw

aii

19,3

51

8

____

____

__So

urce

:Uni

ted

Stat

esD

epar

tmen

tofC

omm

erce

,Bur

eau

ofth

eC

ensu

s,1980CensusofPopulation

,Was

hing

ton,

DC

,198

1.

Puerto

Rican

sin

theUnitedStates,1

980

Dis

trib

utio

nby

Stat

es

9

States with Major Puerto Rican Populations,1980, 1970 and 1960

Percent of Puerto Rican1980 1970 1960 Population in the

United States

State Rank Total Rank Total Rank Total 1980 1970 1960

NewYork 1 986,389 1 916,608 1 642,622 49.0 64.1 72.0

New Jersey 2 243,540 2 138,896 2 55,351 12.1 9.7 6.2

Illinois 3 129,165 3 87,477 3 36,081 6.4 6.1 4.0

Florida 4 94,775 7 28,166 6 19,535 4.7 2.0 2.2

California 5 93,038 4 50,929 4 28,108 4.6 3.6 3.2

Pennsylvania 6 91,802 5 44,263 5 21,206 4.6 3.1 2.4

Connecticut 7 88,361 6 37,603 7 15,247 4.4 2.6 1.7

Massachusetts 8 76,450 8 23,332 11 5,217 3.8 1.6 0.6

Ohio 9 32,442 9 20,272 8 13,940 1.6 1.4 1.6

Texas 10 22,938 13 6,333 10 6,050 1.1 0.4 0.7

Hawaii 11 19,351 10 9,284 12 4,289 1.0 0.6 0.5

Indiana 12 12,683 11 9,269 9 7,218 0.6 0.6 0.8

Michigan 13 12,425 14 6,202 13 3,806 0.6 0.4 0.4

Wisconsin 14 10,483 12 7,248 14 3,574 0.5 0.5 0.4

Virginia 15 10,227 15 4,098 15 2,971 0.5 0.3 0.3

Totals 1,924,069 1,389,980 865,215 95.5 97.0 97.0

__________Sources: 1980 United States Census Supplementary Report S1-7; 1968 United States Census, “Puerto Ricans in the United States,” PC (2)

1K, Table 15, pp. 103–104; and United States Census, “Persons of Spanish Ancestry,” PC (SI)-30, February 1973, Table I, p. 1.In compiling this data, the Migration Division noted that “actual figures may be much higher due to a Census Bureau undercountof minority groups on the mainland.”

both the language and social studies requirements ofgrades 3–4, 5–6 and 7–9. These essays are in black-line-master format and appear in their respective grade-specific teacher’s guides. Learning activities found ineach teacher’s guide encourage the use of these studentessays both in the classroom and at home.

The Americans All® student essays provide back-ground information on Native Americans, AfricanAmericans, Asian Americans, European Americans,Mexican Americans and Puerto Rican Americans, aswell as on Angel Island, Ellis Island and the Statue ofLiberty. Adapted from the Americans All® resourcetexts, the student essays have been created to meet

10

Student Background Essays

437. Puerto Ricans, like many others, migrated whenjob opportunities looked better in the UnitedStates than at home. This man, caught as a stow-away in New York, c. 1900, may have beenlooking for opportunities not available to himat home.

438. The Puerto Rican Department of Labor helpsworkers find jobs in the United States. Thisemployment service office in Caguas, Puerto Rico,provided information during the AgriculturalWorkers Recruitment Program in the 1950s.

439. In many instances migration from Puerto Rico hasbeen a response to economic changes that yieldedincreasingly large numbers of displaced and surplusworkers. This man is going through customs inspec-tion as he prepares to leave for the United States.

440. Many Puerto Ricans were attracted to the UnitedStates by the promise (or hope) of a better life, alife like the one they perceived other Americancitizens had. They were also pulled by connec-tions to family already in the United States. (left)These children pose on a sidewalk in New York’sSouth Bronx, a major Puerto Rican community inthe 1940s. (right) Family pride is evidenced in thisNewYork City portrait, c. 1950s.

441. During World War II, the Kennecott Copper Mineat Bingham Canyon, Utah, faced a serious laborshortage. Pablo Velez Rivera, a drilling machineoperator from Santurce, Puerto Rico, was one ofthe workers brought to the mainland to ease thatcrisis. He is shown with his family as he preparesto drink a cup of coffee made from beans that hisfriends back home sent to him.

442. Puerto Ricans are immigrants because they arrivewith a different culture and language, but they aremigrants because they come as United States citi-zens. The sense of community has always beenstrong, and the family unit has remained the keyto its strength. (top) A group of Puerto Ricansposes on a New York rooftop in the early 1940s.For Puerto Ricans, as for many immigrant andmigrant groups before them, rooftops would serveas one refuge from the crowded urban environ-ment. (bottom) This family portrait was taken inthe 1940s.

443. The daughter of a Puerto Rican barber in theSouth Bronx, New York, poses with a barberworking in her father’s shop. Her father was oneof many people operating Puerto Rican-ownedbusinesses in NewYork.

444. The owner of a bodega (grocery) instructs his staffon products in the store. Commercial estab-lishments mushroomed in the Puerto Rican neigh-borhoods of New York in the late 1940sand 1950s.

445. Although the grocery stores were designed to beself-service, many establishments, such as thisBrooklyn bodega, La Flor de Borinquen (TheFlower of Puerto Rico), set up a delivery systemfor its clients. By providing extra service andattention to the community, stores like this wereable to grow and build a future for their immigrantowners, c. 1948–1955.

446. Many Puerto Ricans left their homeland to pursueadventure and try their luck in a new land. Thisgroup of Puerto Rican women, recruited throughthe Puerto Rican Department of Labor’s MigrationDivision in Chicago, works in the Wabash FrozenFood Packing House, July 1951.

447. English-language classes eased agricultural work-ers’ transition to America. Bilingual instructorstaught new arrivals a basic work vocabulary.

448. Herman Badillo (center in top hat) leads the 1967Puerto Rican Parade, the largest annual PuertoRican event in New York City. Badillo, thenBronx Borough president, went on in 1970 tobecome the first Puerto Rican elected to theUnited States Congress.

449. (top) Dancers entertain themselves and others at thePalladium, a famous New York Latin music ball-room of the 1950s. Puerto Ricans were leading pro-ducers and consumers of the music that came to becalled “Latin” or “Salsa.” (bottom) Immigrantsbrought their music with them, including thisPuerto Rican band in New York, c. 1950. Suchgroups proliferated in the Puerto Rican communi-ties of NewYork, Chicago and Philadelphia.

450. Garcia and Gonzalez, two Puerto Rican soldiers,pose during a break in their training at FortBenning, Georgia, soon after the United States

11

The Photograph Collection

entered into World War II. As American citizensmany Puerto Ricans, both from the island and themainland, have served with distinction in theAmerican military.

451. Representatives of the League of Women Votersexplain how to use the voting machine as part of aninstructional program conducted by the MigrationDivision of the Puerto Rican Department of Laborin NewYork, c. 1959.

452. In 1969 the Council of Puerto Rican andHispanic Organizations led a protest march to theoffices of New York City’s Education Council tobring attention to their members’ social andcultural rights.

453. Puerto Ricans in New York participate in theFiesta San Juan, an annual religious festival spon-sored by the Catholic Church, June 15, 1958.

454. Miriam Colón Valle, president and founder of thePuerto Rican Traveling Theatre Company, Inc.,was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, to a working-class family. At a young age, she moved to the

Santurce section of San Juan, where she devel-oped her love for theater. She came to theUnited States on a special scholarship createdfor her by the University of Puerto Rico to trainat Erwin Piscator’s Dramatic Workshop andTechnical Institute in NewYork City. She becamethe first Puerto Rican accepted at the famedActor’s Studio and co-founded the Nuevo CirculoDramatico, the first Spanish-language arena the-ater in New York. She has appeared in severalBroadway shows and major films and has broughtmany plays by dramatists from other countries tothe American stage. Ms. Colón has served on theNew York State Council on the Arts, on theExpansionArts Panel of the National Endowmentfor the Arts and as a member of the NationalHispanic Task Force. As a result of her achieve-ments both in the theater and as a civic leader, shehas received numerous regional and nationalawards and honors, including honorary doctoratedegrees from many universities.

12

13

437

Stowaway caught on a ship in NewYork

438

Recruitment in Puerto Rico

439

Customs inspection

440

Children and a family in NewYork City

441

Pablo Velez Rivera and family

442

Family and community portraits

443

Barber shop owner’s daughter and barber

444

Grocer and his staff

445

Delivery van and driver

446

Workers in Chicago

447

English-language lessons

448

Herman Badillo leads a parade

14

449

Dancers and band in NewYork City

450

Two Puerto Rican soldiers

451

Learning to vote

452

A protest march

453

Fiesta San Juan

454

Miriam Colón Valle

Cabranes, José A. KF4720.P83C3Citizenship and the American Empire: Notes on the LegislativeHistory of the United States Citizenship of Puerto Ricans. NewHaven, CT:Yale University Press, 1979.

Chenault, Lawrence F128.9.P8C5The Puerto Rican Migrant in New York City. New York, NY:Columbia University Press, 1970. Reprint of the 1938 edition.

Colon, Jesus F128.9.P85C64A Puerto Rican in New York, and Other Sketches. New York, NY:International Publishers, 1982.

Cruz-Monclova, Lidio Z1003.5.P9C78El Libro Y Nuestra Cultura Literaria. San Juan, PR: Sociedad deBibliotecarios de Puerto Rico, 1974.

Dietz, James L. HC154.5.D54Economic History of Puerto Rico: Institutional Change and CapitalistDevelopment. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Fishman, Joshua A.,Robert L. Cooper and Roxana Ma P41.F48Bilingualism in the Barrio. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UniversityPress, 1971.

Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. F128.9.P85F57Puerto Rican Americans: The Meaning of Migration to the Mainland.With a foreword by Milton M. Gordon. Second edition. EnglewoodCliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1987.

Gist, Noel Pitts and Anthony Gary Dworkin HT1523.G57The Blending of Races: Marginality and Identity inWorld Perspective.NewYork, NY: Wiley-Interscience, 1972.

Gosnell, Patricia Aran F128.9.P8G68The Puerto Ricans in New York City. New York, NY: New YorkUniversity Press, 1949.

Handlin, Oscar F128.9.A1H3The Newcomers: Negroes and Puerto Ricans in a ChangingMetropolis. New York Metropolitan Region Study. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press, 1959.

Hernandez, Jose HD8081.P8H47Puerto Rican Youth Employment. Maplewood, NJ: Waterfront Press,1983.

Hidalgo, Hilda and Joan L. McEniry, eds.Hispanic Temas. Newark, NJ: Rutgers University, Puerto RicanStudies Program, 1985.

National Commission on SecondaryEducation for Hispanics LC2670.4.N38Make Something Happen: Hispanics and Urban High School Reform.2 vols. Washington, DC: Hispanic Policy Development Project, 1984.

E184.S75H583The Hispanic Population of the United States: An Overview—A Report. Prepared by the Congressional Research Service for theSubcommittee on Census and Population of the Committee on thePost Office and Civil Service, United States House ofRepresentatives.Washington, DC: United States Government PrintingOffice, 1983.

Iglesias, Cesar Andreu, ed. F128.9.P85V4313Memorias de Bernardo Vega: Una Contribucion a la Historia de laComunidad Puertorriquena en Nueva York. English: Memoirs ofBernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto RicanCommunity in New York. Translated by Juan Flores. New York, NY:Monthly Review Press, 1984.

Jennings, James and Monte Rivera, eds. E184.P85P8Puerto Rican Politics in Urban America. Foreword by HermanBadillo. Contributions in Political Science 0147-1066, no. 107.Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984.

Lewis, Gordon K. F1958.L4Puerto Rico: Freedom and Power in the Caribbean. New York, NY:Monthly Review Press, 1963.

Lewis, Gordon K. F1976.L48Notes on the Puerto Rican Revolution: An Essay on AmericanDominance and Caribbean Resistance. New York, NY: MonthlyReview Press, 1975.

Lopez, Adalberto and James Petras, eds. HN233.L66Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans: Studies in History and Society.Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co.; distributed by HalstedPress, NY, 1974.

Lopez, Alfredo F128.9.P85L66The Puerto Rican Papers: Notes on the Re-Emergence of a Nation.Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973.

Maldonado, Edwin JV6001.I55“Contract Labor and the Origins of Puerto Rican Communities in theUnited States.” International Migration Review, no. 13, 1979.

Maldonado-Denis, Manuel F1975.M2713Puerto Rico: Una Interpretacion Historico-Social. English: PuertoRico: A Socio-Historic Interpretation. First American edition.Translated by Elena Vialo. NewYork, NY: Random House, 1972.

15

Bibliography

Mills, C. Wright, Clarence Senior and Rose Goldsen F128.9.P8M5The Puerto Rican Journey: New York’s Newest Migrants. New York,NY: Russell & Russell, 1967. Reprint of the 1950 edition.

Mohr, Nicolasa PS3563.O36R58Rituals of Survival: A Woman’s Portfolio. Houston, TX: Arté PublicoPress, 1985.

Morales, Julio JV7381.Z79U65Puerto Rican Poverty and Migration: We Just Had to Try Elsewhere.Praeger Special Studies, Praeger Scientific. New York, NY: Praeger,1986.

NewYork City Board of Education LC2698.N48A43The Puerto Rican Study, 1953–1957: A Report on the Education andAdjustment of Puerto Rican Pupils in the Public Schools of the Cityof New York. NewYork, NY: Oriole Editions, 1972.

NewYork City, City University of NewYork, Center forPuerto Rican Studies, History Task Force HD5744.A6N48Labor Migration under Capitalism: The Puerto Rican Experience.History Task Force, Centro de Estudios Puertorriquenos. New York,NY: Monthly Review Press, 1979.

Padilla, Elena F128.9.P8P3Up from Puerto Rico. New York, NY: Columbia University Press,1958.

Padilla, Felix F548.9.M5P32Latino Ethnic Consciousness: The Case of Mexican-Americans andPuerto Ricans in Chicago. Notre Dame, IN: University of NotreDame Press, 1985.

Padilla, Felix F548.9.P85P33Puerto Rican Chicago. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre DamePress, 1987.

Paredes, GustavoDocumentary on Latin Music. New York, NY: Latin AmericanMusicians Association, 1984.

Rivera, Edward PS3568.I829F3Family Installments: Memories of Growing Up Hispanic. First edi-tion. NewYork, NY: Morrow, 1982.

Rodríguez, C., Virginia Sanchez-Korroland Jose Oscar Alers, eds. E184.P85P82The Puerto Rican Struggle: Essays on Survival in the U.S. NewYork,NY: Puerto Rican Migration Research Consortium, 1980.

Rodríguez, Clara E. E184.P85R59Puerto Ricans, Born in the U.S.A. London, UK: Unwin Hyman, Ltd,Academic Division, 1989.

Rodríguez de Laguna, Asela, ed. PQ7420.15.I43Images and Identities: The Puerto Rican in TwoWorld Contexts. NewBrunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1987.

Rogler, Lloyd H., and Rosemary Santana-CooneyPuerto Rican Families in NewYork City: Intergenerational Processes.Maplewood, NJ: Waterfront, 1984.

Sanchez, Maria andAntonio M. Stevens-Arroyo, eds. F1970.8.T68Toward a Renaissance of Puerto Rican Studies: Ethnic and AreaStudies in University Education. Boulder, CO: Social ScienceMonographs; Highland Lakes, NJ: Atlantic Research andPublications; distributed by Columbia University Press, 1987.

Sanchez-Korrol, Virginia E. F128.9.P85S26From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in NewYork City, 1917–1948.Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983.

Santiago-Santiago, Isaura KF228.A84S25Aspira Versus Board of Education of the City of NewYork: A History.Richard Hiller and Herbert Teitelbaum, contributors. New York, NY:Aspira of NewYork, 1977.

Senior, Clarence Ollson E184.P85S4The Puerto Ricans: Strangers—Then Neighbors. Chicago, IL:Quadrangle, 1965.

Stevens-Arroyo, Antonio andAna Maria Diaz-Stevens E184.A1M545“Puerto Ricans in the States . . . A Struggle for Identity.” TheMinorityReport: An Introduction to Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Relations.Second edition. Edited by Anthony G. Dworkin and Rosalind J.Dworkin. New York, NY: CBS College Publishing, Holt, Rinehart &Winston, 1982.

Thomas, Piri F128.9.P8T5Down These Mean Streets. NewYork, NY: Knopf, 1967.

Tumin, Melvin and Arnold Feldman HN240.Z9S67Social Class and Social Change in Puerto Rico. Second edition. ASocial Science Research Center Study. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill,1971.

United States Commission on Civil RightsPuerto Ricans in the Continental United States: An Uncertain Future.Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1976.

United States–Puerto Rico Commissionon the Status of Puerto Rico F1958.U562Status of Puerto Rico: Selected Background Studies. Prepared for theUnited States–Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico.NewYork, NY: Arno Press, 1975.

Wagenheim, Kal E184.P85W33A Survey of Puerto Ricans on the U.S. Mainland in the 1970s. NewYork, NY: Praeger, 1975.

Wagenheim, Kal andOlga Jimenez de Wagenheim, eds. F1971.W3The Puerto Ricans: A Documentary History. NewYork, NY: Praeger,1973.

Williams, Eric F1621.W68From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean, 1492–1969.NewYork, NY: Harper & Row, 1970.

Young Lords Party F128.9.P85Y6Palante:Young Lords Party. Photography by MichaelAbramson. Firstedition. NewYork, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1971.

16

Zentella, Ana Celia P377.L3“Language Variety among Puerto Ricans.” Language in the U.S.A.Edited by Charles Ferguson and Shirley Brice Heath. Cambridge, UK,and NewYork, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Notes: This bibliography was compiled by the author at the time thepublication was originally created.

Library of Congress call numbers have been provided wheneverpossible.

17

Photo Credits

The author is grateful to the following for their aid inthe search for unusual and interesting photographs withwhich to illustrate the text. In some instances, the samephotograph was available from more than one source.When this occurred, both sources have been listed andthe reference number is included for the photograph sup-plied by each organization.

Front Covertop left The Puerto Rican Department of Labor’s

employment service office in Caguas,Puerto Rico, providing information toagricultural workers.The Historical Archives of the PuertoRican Migration to the United Statesunder the custody of the Centro deEstudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 438

top right This Brooklyn bodega, La Flor deBorinquen (The Flower of Puerto Rico),set up a delivery system, providing extraservice and attention to the community.The Justo A. Martí PhotographicCollection, Centro de EstudiosPuertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY,photo 255

bottom left Garcia and Gonzalez, two Puerto Ricansoldiers, during a break in their training atFort Benning, Georgia.Collection of Carlos and Lena Rodríguez,photo 259

bottom right Portrait of a large family, taken in the1940s.Mrs. Clarita Rodríguez, photo 250

Back Covertop The Portfolio Project, Inc., photo 44

bottom The Portfolio Project, Inc., photo 45

Textpage 4 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,

Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 715

page 5 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 257

page 6 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under thecustody of the Centro de EstudiosPuertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY,photo 438

The Photograph Collection437 Lewis W. Hine Collection, United States History,

Local History and Genealogy Division, The NewYork Public Library, Astor, Lenox and TildenFoundations, Unit 5, photo 55

438 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 438

439 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 439

440 (left) Mrs. Clarita Rodríguez, photo 248; (right)The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 249

441 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 441

442 (top) Mrs. Clarita Rodríguez, photo 251; (bottom)The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 250

443 Collection of Carlos and Lena Rodríguez,photo 252

444 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 254

445 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 255

446 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 446

447 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 447

448 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 256

449 (top) The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 258; (bottom) The Justo A.Martí Photographic Collection, Centro de EstudiosPuertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY, photo 257

450 Collection of Carlos and Lena Rodríguez,photo 259

451 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 451

452 The Historical Archives of the Puerto RicanMigration to the United States under the custodyof the Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 452

453 The Justo A. Martí Photographic Collection,Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, HunterCollege, CUNY, photo 261

454 Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre Company, Inc.,identification number unknown

18

Missouri

Arkansas

Louisiana

Mississippi

Alabama

Tennessee

Georgia

SouthCarolina

Kentucky

Iowa

IllinoisIndiana

Ohio

Michigan

Virginia

NorthCarolina

WestVirginia

Pennsylvania

New York

Rhode Island

Massachusetts

Connecticut

New Jersey

Delaware

Maryland

District of Columbia

Florida

GULF OF MEXICO

YucatanPeninsula

CUBA

JAMAICA HAITI

DOMINICANREPUBLIC

PUERTO RICO

ATLANTIC OCEAN

N

W

S

E

PUERTO RICO

Mayaguez

Arecibo

PonceGuayama

Humacao

Carolina

Bayamon San Juan

Culebra Island

Vieques Island

MILES

0 5 10 15 20

c. 1989