7pm - · PDF filetwo pianos and for solo piano. ... performed his two-piano transcription of...

Transcript of 7pm - · PDF filetwo pianos and for solo piano. ... performed his two-piano transcription of...

3 | Sydney Symphony

presenting partner

2011 SeaSon

InTeRnaTIonaL PIanISTS In ReCITaLPReSenTeD BY THeMe & VaRIaTIonS

City Recital Hall angel Place

PROGRAM CONTENTS

Monday 7 March | 7pm

Jean-eFFLaM BaVoUZeT plays Beethoven, Debussy and Liszt

PAGE 5

Monday 16 May | 7pm

PaSCaL & aMI RoGÉ play piano duos from Germany and France

PAGE 15

Monday 4 July | 7pm

InGRID FLITeR plays Beethoven and Chopin

PAGE 23

Monday 1 August | 7pm

FReDDY KeMPF plays Beethoven and Liszt

PAGE 33

This program book for International Pianists in Recital contains notes and articles for all four recitals in the series. Copies will be available at every performance, but we invite you to keep your program and bring it with you to each recital. As in the past, please share with your companion.

Dear Piano Lovers

William Steinway, son of Steinway & Sons founder Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg, was a man before his time – or perhaps more accurately, a marketing trailblazer. Long before Australian sporting personalities began endorsing fast food outlets, William Steinway knew the value of name recognition.

There could be nothing better, he thought, than to have pianists like the famed Anton Rubinstein playing Steinway & Sons. The success of Rubinstein’s musical collaboration with Steinway began a tradition which endures today.

In 2011, more than 98 per cent of the world’s active concert pianists bear the title ‘Steinway Artist’. Each owns a Steinway, and all choose to perform on Steinway pianos exclusively. Importantly, none is paid to do so. This list of more than 1,500 artists includes two pianists who are performing in the recital series this year: Pascal Rogé and Ingrid Fliter.

At Theme & Variations we, too, continue to support this important tradition by keeping our eyes out for the next Young Steinway Artist. Through our Emerging Artist program – which gives secondary and tertiary students the opportunity to gain performance experience – we hope to contribute to the growing pool of Australian talent who are recognised internationally.

We trust you will enjoy this year’s recitals and we look forward to seeing you at City Recital Hall Angel Place or in our Willoughby showroom.

ArA And nyree VArtoukiAn

5 | Sydney Symphony

2011 SeaSon

InTeRnaTIonaL PIanISTS In ReCITaLPReSenTeD BY THeMe & VaRIaTIonS

Monday 7 March | 7pm City Recital Hall angel Place

Jean-eFFLaM BaVoUZeT In ReCITaL

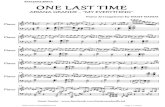

LUDwIG Van BeeTHoVen (1770–1827)Piano Sonata no.8 in C minor, op.13, Pathétique

Grave – Allegro di molto e con brio Adagio cantabile Rondo (Allegro)

CLaUDe DeBUSSY (1862–1918)

Clair de lune (from Suite bergamasque)

Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut(from Images, Series 2)

La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune(from Préludes, Book 2)

FRanZ LISZT (1811–1886) after RICHaRD waGneR (1813–1883)

Isolde’s Liebestod – closing scene from Tristan und Isolde, S447

InTeRVaL

DeBUSSY arranged BaVoUZeT

Jeux – Poème dansé

LISZT

Grosses Konzertsolo, S176

This concert will be recorded for later broadcast on ABC Classic FM.

Pre-concert talk by Robert Murray at 6.15pm in the First Floor Reception Room.

Visit sydneysymphony.com/talk-bios for speaker biographies.

Estimated durations: 20 minutes, 15 minutes, 7 minutes, 20-minute interval, 17 minutes, 22 minutes

The concert will conclude at approximately 8.55pm.

presenting partner

6 | Sydney Symphony

In THe GReen RooM

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet grew up in the city of Metz. It’s one of those cities which was ‘for many years German, then French, then German, then again French’, but it was also the location of one of the most important contemporary music festivals through the 1970s. ‘All the great composers – Messiaen, Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti – they would come to Metz to present their new work,’ says Bavouzet, ‘and this was a big influence on me.’ In particular, he was influenced by electro-acoustique music. ‘From this I learned what sound was all about, because on the synthesizers at that time you had to create your own sound from scratch. This enriched my musical approach and it developed my way of listening.’

Bavouzet toyed with composition himself but soon realised this was not what he could do best. He’d been studying piano, oboe and percussion at the conservatorium in Metz and was interested in jazz. At the Paris Conservatoire he began to focus on piano, and although he hadn’t necessarily been dreaming of a career as a pianist, by the age of 23 or 24 he’d entered the world of professional pianists.

Since then, the way of listening nurtured in Metz has placed him in good stead. One of the challenges he set himself was making playable transcriptions of Debussy’s ballet Jeux – for two pianos and for solo piano. The process is akin to translating a text. ‘In the case of Jeux, you have one of the most complex orchestral scores ever written and somehow you have to adapt it. Even in the two-piano version I had to make some very big

PA

ul

MIT

Ch

Ell born

Metz, in eastern France

studied with Pierre Sancan at the Paris Conservatoire

early success in 1985 won the International Beethoven Competition in Cologne and the Young Concert artists auditions in new York

big break was invited by George Solti to make his debut with the orchestre de Paris in 1995, and is widely considered the maestro’s last discovery

solo recordings has recently completed an award-winning five-disc set of the complete solo piano works of Debussy; his current project is a recording of the complete Haydn sonatas

Jeux transcriptions during the late 1990s he performed his two-piano transcription of Debussy’s Jeux with Zoltán Kocsis in duo recitals throughout europe; his solo transcription was prepared for the complete Debussy recording and this recital will be its concert premiere

in Australia this is his Sydney Symphony debut and his first visit to australia

further listening See More Music on page 41

Jean-efflam Bavouzet in conversation

7 | Sydney Symphony

choices, because 20 fingers were not enough to play everything that was in the score. So if 20 fingers is not enough, you may wonder how ten fingers might be!’

In a transcription such as Jeux, many things have to be left out – you can’t expect a piano to have the same variety of colour or texture as an orchestra. ‘But,’ says Bavouzet, ‘what you gain is a clear approach. Your attention is not taken by all the wonderful colours of the orchestra, so you are more aware of the musical structure and the connections between Debussy’s language for orchestra and his original piano writing, for example the Etudes.’

Bavouzet’s program for his Sydney recital debut is rich in connections of another kind. There’s an underlying ‘Night’ theme, with the three Debussy moonlight pieces. ‘The night is also very present in Tristan und Isolde,’ he continues, ‘and the setting of Jeux as a ballet is at night. It’s an erotic fantasy between a young man and two young women – so we have night and also eros.’

The other theme is one of ‘passion and pathos’. This emerges in Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata as well as in the Grand solo de concert, which goes by the name ‘Concerto pathétique’ in its two-piano version. And while the ‘pathétique’ in the titles is simply coincidence, ‘the gestures in each work are just as dramatic, even with very different languages. The state of mind, the musical rhetoric and declamation are very similar.’ In another sense the two works are opposites: the Pathétique is one of Beethoven’s best-known sonatas; the Grand solo de concert is neglected Liszt. But Bavouzet believes Liszt cherished it very much, not least because he wrote three versions of it. ‘And I’m absolutely convinced that without the Grand solo de concert, Liszt’s B minor sonata would never have existed. In this piece, and for the first time, Liszt is trying to deal with the one-movement sonata. The Grand solo de concert is his first attempt at this structure and architecture. It’s also very similar to the B minor sonata in its semantic qualities: I could play the main themes right after each other and you’d see immediately the relationship.’

There’s a third theme to the program – one which became clear to Bavouzet only later. This is the idea of the piano as orchestra. It emerges in the transcriptions (Jeux and the Liebestod) and in the sometimes orchestral character of the Beethoven sonata, as well as in Liszt’s orchestral conception for his Grand solo de concert. But it also emerges in the three moonlight pieces of Debussy. ‘I believe a good Debussy pianist should give the audience the illusion that the music is an orchestral transcription.’ There’s a piano on the stage, but close your eyes and perhaps you’ll hear an orchestra.

YVONNE FRINdlE, SYdNEY SYMPhONY ©2011

ashkenazy records Jeux

‘Before we actually met and certainly long before we ever played together, Maestro Ashkenazy called me and asked permission to be the first to record my two-piano transcription of Jeux. I could not believe it! I said, “But Maestro, nothing better could happen to this score! Of course I give you my permission.” I thought, how elegant and really so incredibly nice of him. And I was very, very touched. he recorded it with his son, and so far it is the only recording of that transcription.’

‘We know for a fact that debussy was obsessed with the language of Wagner at the beginning. It was an obsession he had to fight to escape from and he succeeded brilliantly. Nevertheless, during his whole lifetime there was always some reminiscence of that. There are very big similarities between the music of the prelude of Tristan und Isolde and La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune. You hear the Tristan chord many times in La terrasse…’

9 | Sydney Symphony

aBoUT THe MUSIC

By moonlight…

Every so often a recital program looks as appealing on paper as it sounds to the ear. This is such a program. It begins with music of passion and intense feeling before entering a twilight world with the music of Debussy and Wagner, a world both ancient and modern. Liszt might seem to bring an abstract conclusion to the recital, but his grand concert solo returns to the ‘pathétique’ conception of Beethoven. In this program, titles are everything: their inspiration and their meanings – real and imagined – provide essential clues to the music.

‘Grande sonate pathétique’ – this is Beethoven’s own title, given to a landmark sonata. The Pathétique Sonata, op.13 resolutely shifted the piano sonata away from its Classical heritage, making it more dramatic and more emotional.

English speakers tend to stumble over ‘pathétique’. Unhelpfully close to ‘pathetic’, the word conjures up ideas of the pitiful and the inadequate well before it makes us think of intense emotion (its archaic meaning) and pathos. Perhaps it’s easiest to remember that the Russian title for Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony (‘Pateticheskaia’) means something like ‘impassioned’. And Beethoven’s opus 13 sonata introduces that quality to his oeuvre with a bold, slow introduction in C minor, the key that was to be associated in his music with fate, heroism and the sublime.

The grandly defiant beginning (Grave) is more than an introduction, as Beethoven reveals by bringing it back as he begins to develop the themes of the allegro and again in the coda. (And perhaps a third time, depending on how the pianist interprets the ambiguity of Beethoven’s instruction to repeat the exposition.) More than one writer has argued that all the thematic material of the sonata derives from the motif in very first bar. William Kinderman reads this motif as a representation of ‘resistance to suffering’ (an idea drawn from Friedrich Schiller’s 1793 essay Über das Pathetische), with the contrast between the aspiring, upward unfolding of the melodic outline over a minor third, and the ‘leaden weight of the C minor tonality’.

The allegro of the first movement is agitated, almost obsessive. It maintains the orchestral effect of the introduction, with unforgiving ‘timpani rolls’ in the left hand. Respite comes in the Adagio cantabile, where we can imagine Beethoven’s famous legato style of playing: sustained and singing, powerfully expressive. In contrast with the drama and ‘strange modulations’ of the first movement, this movement is a model of simplicity. The

Beethoven

At this time I heard from some of my fellow pupils that a young composer had arrived in Vienna who wrote the most extraordinary stuff, which no one could either play or understand; a baroque music in conflict with all the rules. This composer’s name was Beethoven. When I went back to the circulating library to satisfy my curiosity…I found Beethoven’s Sonate Pathétique. That was in 1804. Since my pocket money did not suffice to buy it, I secretly copied it out.

IGNAZ MOSCHELES

10 | Sydney Symphony

Debussy

exquisite theme appears three times, separated by two episodes – one lyrical, the other agitated.

Beethoven is reported to have played the rondo theme of the third movement humorously, and there is a relaxation from the high seriousness of the first two movements. The defiance of the first movement here turns to contemplation at times, but the minor-key conclusion brings a culmination of the drama and intensity of the whole.

Three pieces by Debussy bring moonlight into the recital hall. Clair de lune (Moonlight) is the third movement of Suite bergamasque, its baroque atmosphere coming from Watteau via Verlaine. The effect of its shimmering overtones and distant bell-like sounds suggests the silvery light of the moon; the rippling arpeggios in the central section hint of the ecstatic fountains in Verlaine’s poem of the same name. There is a ghostly, static quality – this is the sound of an imagined past. At the same time, this relatively early work of Debussy’s points to the future, with his use of parallel, ‘non-directed’ harmonies and the attention he gives to the acoustical possibilities of the piano.

et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut (The moon descends over the temple that was) comes from the second set of Images (1907). This title is significant. On the one hand, ‘Images’ suggests pictures, but perhaps they are moving pictures. Debussy is known to have regarded music – an art form that exists in time – as having a closer affinity with cinema than with painting. As he told one young composer: ‘Music has this over painting: that it can bring together all variations of colour and light.’

Clair de lune

Your soul is like a landscape fantasy, Where masks and Bergamasks, in charming wise, Strum lutes and dance, just a bit sad to be hidden beneath their fanciful disguise.

Singing in minor mode of life’s largesse And all-victorious love, they yet seem quite Reluctant to believe their happiness, And their song mingles with the pale moonlight,

The calm, pale moonlight, whose sad beauty, beaming, Sets the birds softly dreaming in the trees, And makes the marbled fountains, gushing, streaming – Slender jets of water – sob their ecstasies.

Translated from Verlaine’s Fêtes galantes (1869)

11 | Sydney Symphony

The title of the piece itself is said to have been suggested by Louis Laloy, the dedicatee, after the music had been composed. Its oriental imagery is a response, therefore, to the floating gamelan effects and use of the exotic five-note scale. As the French pianist Marguerite Long describes it in At the Piano with Debussy: ‘Here is a new paradox in music: for an image of silence is achieved by means of sound. Two muffled kettledrums resound like a gong in the dead temple, whence breaks forth a monody of phantom melody and the counterpoint of its reply.’

Debussy drew the title ‘La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune’ (Préludes, Book 2) from a letter in Le Temps. The ‘esoteric and remote text’ pleased Debussy, recalls Long, ‘and he drew from it one of his most original evocations’. The context was a description of the coronation of George V as Emperor of India, describing ‘the hall of victory, the hall of pleasure, the garden of the sultanesses, the terrace for moonlight audiences’.

The oriental setting emerges in music through delicate, sinuous melody, more bell-like gamelan effects, and a drowsy poetry of sound. At the same time (Long again) there are moments of ‘primitive effort’ in which the music ‘suddenly attains a lunar force which raises tides’.

Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde comes to its ecstatic conclusion with both lead characters sunk in the Night of Forgetfulness, the sublime release of death – Tristan from a fatal wound, Isolde following. She sings through endless melody, breathing her life away, in utmost rapture. It was the last opera of Wagner’s that Liszt heard before his own death.

Wagner called this great final scene ‘Transfiguration’. We have Liszt to thank, says pianist Leslie Howard, for ‘Liebestod’ (Love-Death), the title which has clung, with Wagner’s approval, to this impassioned farewell to love and life.

Liszt’s piano transcriptions from opera belong to a noble 19th-century tradition. They are all impressive in their imagination and virtuosity, but the remarkable eloquence of Isolde’s Liebestod reveals the great admiration Liszt had for Wagner’s work. Wagner, for his part, once declared that ‘not a note’ of his music would be known but for Liszt.

Isolde’s Liebestod is a faithful transcription, rather than a free fantasy, but in taking the scene from its larger context, Liszt needed to provide an introduction. Surviving sketches show the trouble he took over this, settling – at his third attempt – on a fragment taken from the love duet of Act II.

what’s in a name?

Et la lune… is an ‘image’; La terrasse… a ‘prelude’. These are just names – perhaps the prelude will be more abstract, the image more overtly pictorial. This idea is reinforced by debussy’s typographical choices for the published pieces. his Images present their titles at the beginning: the title gives the pianist a point of departure. The titles of the Préludes, however, appear at the end of each piece (…in parentheses) as a point of arrival. And yet the Images are the more abstract works – even named after completion – while the two books of Préludes convey a more concrete imagery.

wagner

12 | Sydney Symphony

Debussy’s ballet Jeux (Games) combines the atmosphere of a moonlit night with themes of love. Its ending is ambiguous, but there is no hint of tragedy or even serious passion. The love-triangle scenario (one boy, two girls) involves flirtation, playfulness, fleeting jealousies and casual ecstasy. The setting is a tennis court in a park, giving a double meaning to the ‘games’ of the title.

Debussy had been unhappy with Nijinsky’s ‘ugly’ and angular choreography for Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, their first ballet for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, but he agreed to write a second for the money. He was also attracted to the scenario and the ‘suggestion of something slightly sinister that the twilight brings’. There is an elusiveness in the music – the huge orchestra is used in subtle, weightless ways, colours are veiled, and it creates a remarkable, dreamlike sound world. Once again, however, Nijinsky trampled over his ‘poor rhythms like a weed’; Debussy sat out the premiere in the concierge’s office, smoking a cigarette.

The sophistication and intricacy of the music is offset by the strength of a simple idea, described by composer Elliott Gyger as ‘the gradual emergence, triumph and dissolution of a waltz-like dance’. This strategy has affinities with La Valse by Ravel, but where Ravel’s music is apocalyptic, ‘the waltzes in Jeux stand for abandonment to the fleeting – perhaps transgressive – pleasures of the moment’.

The ballet composer is invariably expected to provide a piano version for use during rehearsal. For Jeux, Debussy wrote additional lines above and below the two traditional piano staves. The implication is that these parts might be discretionary, and yet they contain essential musical elements. As Jean-Efflam Bavouzet points out, the result is genuinely unplayable in places – he imagines the ‘aghast expression’ of the Ballets Russes pianist – and his frustration led him to prepare first a two-piano version and more recently a version for solo piano, which he admits is probably one of the most difficult works he has ever performed.

So far this recital has offered a string of attractive titles: Beethoven’s ‘Pathétique’, Debussy’s poetic references to the moon (Et la lune… is in the 12-syllable Alexandrine of classical French verse), Liszt’s gift to Wagnerians in ‘Liebestod’, the delicious ambiguity of ‘Jeux’. The title of the final work, however, is not beautiful.

lEB

REC

hT

Mu

SIC

& A

RTS

nijinsky in the Paris (1913) production of Jeux. (Photograph by Charles Gerschel)

13 | Sydney Symphony

Grosses Konzertsolo (Grand Concert Solo) may not be evocative, but in its pragmatism it points to the goal Liszt was pursuing. The possibilities he considered – including ‘Concerto sans Orchestre’ – reveal his struggle to effectively characterise the music. In the end, as Leslie Howard sums it up, Liszt made ‘a mere stab’ at a title for a long work which is not yet a sonata but is no longer a character piece.

It was composed between 1849 and 1850, intended as a competition piece for the Paris Conservatoire. It was regarded as supremely difficult. The dedicatee Adolf von Henselt declared he was unable to play it. Clara Schumann declined to perform it – although this may have been a matter of taste rather than technique. Carl Tausig is thought to have given the premiere.

In private Clara Schumann had disparaged the music’s empty virtuosity. But this is surface stuff. The Grosses Konzertsolo is interesting for its musical innovations and for its place as a forerunner to the great Sonata in B minor.

Like the Sonata, the Grosses Konzertsolo is in a single movement of contrasting sections, played continuously. Both works represent a logical development of the classical sonata genre, taking it from the multi-movement work to a large-scale unified conception in which all the material derives from a single theme or set of ideas. Structurally and thematically, the Grosses Konzertsolo reveals original thinking which was to come to fruition in the Sonata.

In its initial form the Grosses Konzertsolo was relatively simple: a one-movement Allegro, more or less in traditional first-movement sonata form. Shortly before the work was first published Liszt added the slow middle section (Andante sostenuto) between what would have been the exposition and development of the main themes, working its material into the later sections of the piece. The Andante sostenuto also incorporated a filigree cadenza, pushing the character of the music in the direction of a piano concerto.

Fifteen years later, Liszt published the work in a version for two pianos. In adding a second instrument, he was free to explore the concerto-like potential of his material – a ‘concerto avec “orchestre”’ perhaps. And with this revision came a new name – Concerto pathétique – which also acknowledges the intensity of expression and heroic character of this majestic virtuoso work.

YVONNE FRINdlE SYdNEY SYMPhONY ©2011

Grosses Konzertsolo

Allegro energico – Grandioso – Andante sostenuto – Allegro agitato assai – Andante, quasi marcia funebre – Tempo giusto (Moderato) – Allegro con bravura

There is a ‘long pause’ before the funeral march section, otherwise the sections are played continuously.

Liszt

15 | Sydney Symphony

2011 SeaSon

InTeRnaTIonaL PIanISTS In ReCITaL PReSenTeD BY THeMe & VaRIaTIonSMonday 16 May | 7pm City Recital Hall angel Place

PaSCaL & aMI RoGÉ In ReCITaLRoBeRT SCHUMann (1810–1856) arranged Claude Debussy

Six etudes in Canon Form, op.56Pas trop vite Avec beaucoup d’expression Andantino Expressivo Pas trop vite Adagio

JoHanneS BRaHMS (1833–1897)

Sonata in F minor for two pianos, op.34bAllegro non troppo Andante, un poco adagio Scherzo (Allegro) – Trio Finale (Poco sostenuto – Allegro non troppo)

InTeRVaL

FRanCIS PoULenC (1899–1963)

ElégieL’Embarquement pour Cythère (The embarkation for Cythera) – Valse-musette for two pianos

PaUL DUKaS (1865–1935)The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Scherzo after a ballad by Goethe arranged by the composer

MaURICe RaVeL (1875–1937)La Valse – Poème chorégraphique arranged by the composer

This concert will be recorded for later broadcast on ABC Classic FM.

Pre-concert talk by dr Robert Curry at 6.15pm in the First Floor Reception Room.

Visit sydneysymphony.com/talk-bios for speaker biographies.

Estimated durations: 18 minutes, 37 minutes, 20-minute interval, 8 minutes, 12 minutes, 12 minutes

The concert will conclude at approximately 8.55pm.

presenting partner

16 | Sydney Symphony

In THe GReen RooM

What could be better than one piano? Two pianos! Put two pianos together in recital, says Pascal Rogé, and the reward is a new power and versatility of sound. The piano duo combination is even more exciting when the two pianists are partners in life as well as in music. ‘We travel together, we practise together and we play together,’ says Pascal. ‘To be able to share music on stage makes the whole story much more personal for us – it is a great joy.’

Pascal Rogé’s background is very French. ‘I was born in Paris, raised in Paris, and studied at the Paris Conservatoire with French teachers,’ he says. ‘I was born with this repertoire.’ Ami Rogé began her musical studies in Tokyo before her family moved to the United States. She ended up in New York as a student at the Juilliard School. Her teachers have included Shu Hao Pao, Oxana Yablonskaya, Leon Pommers and Sophia Rosoff. ‘At first glance,’ says Pascal, ‘there’s no connection with French music, but I discovered that Ami had been interested in that repertoire long before we met. And she speaks French fluently!’

‘My students always ask me, “Do we have to be French to play French music?” and I say “No, of course not.” But you have to love French culture and to be immersed not only in the music, but the art, the wine, the country itself – all that is part of understanding the French style.’ The love of French music and French culture provided important common ground for the two when they met. ‘We have a lot in common outside music,’ says Ami, as they begin to rattle off the list:

NIC

k G

RA

NIT

O born Pascal in Paris; ami in Tokyo to a Japanese mother and Indonesian father

studies Pascal at the Paris Conservatoire; ami in Tokyo, then the Juilliard School in new York and Mannes College

beyond piano ami also studied harpsichord with arthur Haas

they met about eight years ago at a festival in Spain

concert appearances have included performances in Carnegie Hall, Beijing International Piano Festival and the 2006 australian Festival of Chamber Music in Townsville

recordings their first recording together is Wedding Cake; they are planning a disc of French duos and duets

new music the CD includes a suite composed for them by Paul Chihara, Ami (2008); in this visit to australia they will premiere a double piano concerto by Matthew Hindson

in Australia Pascal has been a regular visitor to Sydney; this is ami’s australian debut

further listening See More Music on page 41

Pascal & ami Rogé in conversation

17 | Sydney Symphony

It’s a Perfect Life

‘We are very privileged to be doing exactly what we love and doing it together and, above all, doing it for the pleasure of other people. It’s a very rewarding thing.’

PASCAL ROGÉ

cooking, fine wine, going to the opera and the movies, museums, travelling… ‘Almost everything we do!’

Twentieth-century French music forms the second half of the festive program they have assembled for Sydney. ‘We wanted to include French music because that’s our principal repertoire,’ says Pascal, ‘but also German music because that is music that we all love and everybody wants to hear.’ It’s a program that reveals two aesthetic approaches to the duo repertoire. ‘Schumann and Brahms approach the two instruments with an orchestral vision, very grande,’ says Pascal. ‘The French pieces are much more intimate and colourful, more impressionistic.’

There’s also the contrast between the ‘so-called serious’ German style, with its reputation for being profound, and the ‘so-called light’ French style, concerned with character and gesture, often more ephemeral. ‘And it’s interesting to see how differently these composers have treated the two pianos and the piano itself – the technique of composing is so different.’

The Rogés’ program mixes music conceived for two pianos and arrangements of pieces that most concert-goers will know better as orchestral works. Some of their repertoire – there are examples in Ravel – was written first for two pianos, and later orchestrated. Perhaps, suggests Pascal, it’s ‘easier for a composer to put down ideas on two instruments, hearing it as a solo piece almost, and then later orchestrate it, rather than thinking of it orchestrally first.’

Some of the music is well known, if not necessarily in its piano duo form. The Brahms Sonata in F minor is much loved as a piano quintet, created, says Pascal, because ‘Clara Schumann told him there were two many notes’! The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is without doubt Dukas’ most famous piece; La Valse has had many outings in Sydney. Then there are the miniatures by Poulenc, showing two sides of the composer in the space of a few minutes – one witty and dance-like, the other nostalgic and melancholy. The elegy for the Princess de Polignac (Winaretta Singer of the sewing machine fortune) is a tender tribute. ‘He has a little quote at the beginning,’ says Pascal, ‘saying this piece should be played with a glass of cognac and a cigar. What he means is that it’s a very relaxed piece and to be enjoyed at the end of the evening.’

This particular evening ends with the collapse of an age in La Valse in music that is as stunning in its two-piano form as it is in orchestral form. One reason the piano duo enjoyed a golden age before the modern era of mechanically reproduced sound was its capacity to bring orchestral repertoire to a wider audience. And with two pianos on the stage ‘you can really feel like you’re an orchestra’.

YVONNE FRINdlE, SYdNEY SYMPhONY ©2011

18 | Sydney Symphony

aBoUT THe MUSIC

Duos in the Golden age

Works for piano duet held a vital role in domestic music-making in the 19th and early 20th centuries. For composers and publishers – without radio, CDs, iPods and other playback devices – there were few methods of dissemination as important as the piano four-hand arrangement. And for musical amateurs, the appetite for works that could be explored in the privacy of the homes was voracious. Dances by Schubert and Brahms, Beethoven’s late quartets or Haydn’s symphonies, reductions of popular operatic scenes and other miscellany: there was an embarrassment of riches available for the humble, but truly mighty, piano duet.

Whereas works for duet were mostly conceived for domestic, private spaces, works for two pianos were almost always intended for concert performance by two virtuosos. Schumann and Brahms were among the first 19th-century composers to really explore the possibilities of two pianos. By the early 20th century, this ‘small orchestra’ had welcomed major contributions from Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff, Debussy, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Bartók and later Poulenc. Waves of composers and piano duo teams would follow. Many composers would routinely make two-piano versions of their own orchestral works, either in the process of composition or at the demand of publishers. Sometimes, as Debussy did with Schumann, they would agree to make transcriptions of music and composers they admired.

This program traverses the golden era of the piano duo, from German robustness to the distinctive sonorities and humour of the French. Some of the works also exist in more familiar chamber, orchestral or solo piano versions, but two-piano performance brings not only an inherent grandeur, but also an intimacy and exciting interpretative concord as is possible between two musicians.

According to Robert Schumann, J.S. Bach was the ‘one source which inexhaustibly provides new ideas’. Schumann’s reverence for the Baroque master would see he and his wife Clara immerse themselves in periods of Bach-inspired study. Clara noted in her diary following one particularly intense immersion in January 1845: ‘Today we began to study counterpoint, which, in spite of the labour, gave me great pleasure…[Robert] has been seized by a regular passion for fugues, and beautiful themes pour from him.’

Some of these ‘beautiful themes’ likely refer to Schumann’s opus 56, the Six Studies in Canonic Form, one of four sets

19 | Sydney Symphony

of contrapuntal pieces he composed that year. They were intended for the pedal piano: a piano with an additional foot-operated keyboard, similar to the pedals of an organ. Its ability to accommodate additional bass lines charmed Schumann. Not long after his death, however, the pedal piano (primarily used as a practice instrument by organists) became almost obsolete, and Clara suggested these might be arranged for piano duet. Among many transcriptions (some of them, logically, for organ) Debussy’s 1891 version for two pianos is perhaps the best known.

Debussy’s admiration for Schumann was similar to that of Schumann’s for Bach. Having first come into contact with Schumann’s work as a student, Debussy completed this transcription three years before his groundbreaking Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1894). Debussy cleverly shares the canonic ideas between the two pianos, much as they are shared between the right and left hands in Schumann’s original.

The first canon immediately suggests Bach, in a texture resembling the Two-Part Inventions and the Toccata and Fugue in F (BWV 540); counterpoint is to the fore, but Schumann’s poetic lyricism is maintained. The other canons are more openly the work of a Romanticist, weaving flowing melodic lines between the instruments, and calling for great sensitivity in the balancing of melody and accompaniment.

Some 17 years after Schumann wrote his Canons, the 28-year-old Johannes Brahms made his first visit to Vienna – the ‘musician’s holy city’. A life-long ambition for the young composer, its realisation coincided with a new level of maturity in his compositions.

The first work to come from this time was his String Quintet in F minor (1862), with the same instrumentation (two violins, viola and two cellos) as the C major quintet of former Vienna resident Franz Schubert. Brahms’ close friends Clara Schumann and violinist Joseph Joachim were deeply impressed, but Joachim warned: ‘The work is difficult, and I fear that without vigorous [string] playing it will not sound clear.’ Joachim was proved right. After a series of unsuccessful rehearsals, a bitterly disappointed Brahms wrote, ‘…it will be better if it goes to sleep.’ He later burnt the manuscript. Over the following year Brahms reworked his quintet for a radically different medium, as the Sonata in F minor for Two Pianos. This was premiered in Vienna on 17 April 1864 with its composer and the famed virtuoso Karl Tausig at the pianos.

Pedal piano by Joseph Brodman, 1815 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Brahms later burnt the manuscript.

20 | Sydney Symphony

Despite the unusually large number of melodic ideas – Brahms presents five themes in the exposition of the first movement alone – there is no indulgence. Throughout the Sonata, the ideas themselves are tightly constructed and integrated; this charges the phrases with an energy helping to propel each of the movements forward. The gentle lilt of the slow movement suggests the influence of Schubert, whilst the brief Scherzo third movement most vividly demonstrates Brahms’ gift for contrasting gestures, with shadowy figures in animated dialogue with the triumphant.

Although Brahms was clearly fond of the duo sonata, he was persuaded to attempt yet another version. Essentially preserving one of the piano parts, he reworked the other for string quartet. The result was the Piano Quintet (Op.34), today the most commonly heard form of this work, and considered a masterwork of chamber music. Proposing the work in this form to his publishers, Brahms also asked if the two-piano version could be published: ‘I still think we must keep the work in mind as a Sonata for two pianos. It appeals to me in this form…’. Brahms continued to perform the Sonata publicly, including with Clara Schumann.

Like Brahms, Frenchman Francis Poulenc made major contributions to the duo repertoire. His miniature elégie (1959) was to be his final work for his own instrument. Despite the title – indicating a memorial work for Poulenc’s friend Countess Edmond de Polignac – the music is not mournful. Poulenc seems to be recalling the cosmopolitan musical soirées at the Princess’s Parisian home: he instructed performers to play it ‘as if improvising, a cigar between your lips and a glass of cognac on the piano’.

Poulenc’s predilection for melody and tonal harmony is also well-demonstrated in the jovial L’embarquement pour Cythère (1951). This buoyant trifle, a valse-musette, was inspired by a painting of the same name by early 18th-century Rococo artist Jean-Antoine Watteau (the same painting inspired Debussy’s piano work L’isle joyeuse). The painting depicts numerous couples enchanted by Cupid, drawing them towards the water where a ship awaits to transport them to the island of Cythère (believed in Greek mythology to be the birth place of Venus, goddess of love).

This clowning work was part of the film score for the French comedy, Le Voyage en Amérique (1952), a decidedly lighter scene than Watteau’s. A reluctant composer for film, Poulenc only relented in this case as the music was to be performed by two American pianists of whom he was fond.

Detail from watteau’s painting The embarkation for Cythera (1717)

21 | Sydney Symphony

Poulenc later instructed the pianists to play a section of the piece ‘thickly, like a bloke’s kiss, in a steady tempo’.

It’s intriguing to imagine what Paul Dukas would have thought of Walt Disney’s 1940 animated film Fantasia: a young magician’s apprentice in the form of Mickey Mouse conjures a spell he is unable to control; his water-bearing brooms start reproducing from splinters, quickly flooding the cauldron and then the castle, all the while marching to a heavily edited version of The Sorcerer’s apprentice in its orchestral form (1897). The fastidious Dukas may not have welcomed the tinkering with his refined score based upon Goethe’s ballad Der Zauberlehrling, but he may have appreciated the popular recognition for which he struggled. Severe self-criticism saw Dukas destroy the manuscripts of all his unfinished works (and also quite a few of those he did complete). One of only 12 works published during a career of more than fifty years, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice became and remained the work by which Dukas’ name is remembered.

Dukas’ orchestration is masterful, as is his ability to create tension through thematic development, but there are also advantages in Dukas’ own two-piano transcription from 1899: while the pianists aspire to suggest ‘orchestral’ colours, the transparency of texture allows thematic detail to be better heard. The opening in which the sorcerer conjures his first spell remains suspenseful, with the flutter of flutes and sliding of violins replaced by shimmering effects and repeated notes of the pianos, delivered through the haze of the sustaining pedal; the directness of piano sound conveys bass pizzicato well, as it does shrieks of high woodwinds. Dukas’ music – in either form, with or without Walt Disney – vividly communicates Goethe’s story.

Maurice Ravel sketched his own surreal scenario on the manuscript of La Valse: ‘Swirling clouds afford glimpses, through rifts, of waltzing couples. The clouds scatter little by little; one can distinguish an immense hall with a whirling crowd. The scene grows progressively brighter. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth at the fortissimo. An imperial court, about 1855.’

With its strong dance and visual associations, Ravel had always intended the work for the stage. When Diaghilev commissioned a score for the Ballets Russes in late 1919, Ravel saw the opportunity to complete sketches for a ballet he’d envisaged some 13 years prior. The composer had projected his work, then titled Wien [Vienna], as: ‘a grand waltz, a kind of homage to the memory of the great Strauss,

Wilt thou, misbegotten devil! drown the house with fiendish funning? For the water o’er the level Of the sill in streams is running. Just a broom-stick frantic, That will hear me never! Be a stick, thou antic! Once more and for ever! Is unending This work dreary? Art not weary? Oh! remit it! Ah! this hatchet stops the offending, For the broom-stick, I will split it!

FROM GOEThE’S BAllAd DAS ZAubERLEhRLInG (Translated William Gibson)

The Sorcerer’s apprentice (illustration by Ferdinand Barth, 1882)

22 | Sydney Symphony

not Richard, the other – Johann.…You know how much I like those wonderful rhythms!’

But the horrors of war changed Ravel’s outlook: by 1919 it was ‘inappropriate to the demands of the time’ to name a work after the capital of Austria. Ravel resumed, but with the new title, La Valse (poème chorégraphique), and a darker, even menacing undercurrent. Ravel’s pupil Manuel Rosenthal described the second half of the work as ‘a kind of anguish, a very dramatic feeling of death’, and Ravel would later confirm: ‘It’s tragic, but in the Greek sense; it is fatal spinning around, the expression of vertigo and of the voluptuousness of the dance to the point of paroxysm.’

Ravel completed the solo piano and two-piano versions before orchestrating the music. The two-piano score was first heard in April 1920 by a small audience including Diaghilev, the choreographer Leonide Massine, Stravinsky and a young Poulenc. Poulenc recalled: ‘I had seen that [Diaghilev] didn’t like it and that he was going to say “No”. When Ravel had finished, Diaghilev said to him something which I thought was very true. He said, “Ravel, it’s a masterpiece…but it’s not a ballet…it’s the portrait of a ballet…it’s the painting of a ballet”.’ Ravel is said to have walked out of the room humbly and quietly, music tucked under his arm, and from that point onwards ceased relations with the impresario.

Ravel depicts the parting of clouds and glimpses of dancing with grumbles in the basses of the pianos, fragments of themes poking through. La Valse throughout gives the impression of fragmentary form; thematic ideas emerge, sometimes bursting through the hazy textures, but just as often receding back into confused memory. Bitonality and the presence of two-beat rhythmic groupings within the three-beat feel of the waltz – described by composer George Benjamin as ‘opposing forces of civilised order and destructive order’ – all add considerably to the hallucinatory effect. Ravel gives the pianos large chordal leaps, double-glissandi, fast passagework and an abundance of trills: this is a challenging but engaging work, even without the orchestra or dance spectacle. As the waltz threatens to whirl out of control, Ravel’s score markings insist upon accelerating, animating, pressing forward, and a little more…until its imaginary dancers can bear no more, collapsing with a shriek.

ANGElA TuRNER ©2011

Ravel

Poulenc

23 | Sydney Symphony

2011 SeaSon

InTeRnaTIonaL PIanISTS In ReCITaL PReSenTeD BY THeMe & VaRIaTIonS

Monday 4 July | 7pm City Recital Hall angel Place

InGRID FLITeR In ReCITaL

LUDwIG Van BeeTHoVen (1770–1827)

32 Variations on an original Theme in C minor, woo.80

Piano Sonata no.18 in e flat, op.31 no.3

Allegro Scherzo (Allegro vivace) Menuetto (Moderato e grazioso) Presto con fuoco

InTeRVaL

FRÉDÉRIC CHoPIn (1810–1849)

nocturne in B, op.9 no.3

waltz in a flat, op.34 no.1 waltz in B minor, op.69 no.2 waltz in D flat, op.64 no.1 (‘Minute’ waltz) waltz in a flat, op.64 no.3 waltz in G flat, op.70 no.1 waltz in a flat, op.42 waltz in a minor, op.Posth.

Ballade no.4 in F minor, op.52

This concert will be recorded for later broadcast on ABC Classic FM.

Pre-concert talk at 6.15pm in the First Floor Reception Room.

Estimated durations: 12 minutes, 20 minutes, 20-minute interval, 5 minutes, 22 minutes, 12 minutes

The concert will conclude at approximately 8.45pm.

presenting partner

24 | Sydney Symphony

Six years ago, in Atlanta, Dan Gustin, director of the Gilmore Society, invited Ingrid Fliter to lunch to discuss her participation in the society’s festival. ‘So I went to have lunch with him,’ recalls Fliter, ‘and in the middle of my salad he told me I had won the Gilmore award! I never thought this could happen to me.’ Fliter was understandably overwhelmed – the Gilmore award is possibly unique in the musical world. ‘It is a very noble initiative,’ she explains, ‘because it is not a competition. Is is the anti-competition.’ Every four years a prestigious jury follows pianists anonymously, attending concerts anywhere in the world, judging performers in their ‘natural habitat’. ‘Your playing is not tinted with any artificial components to impress a jury,’ says Fliter. ‘And if you don’t win you’re not disappointed because you didn’t know you were being judged!’ This life-changing award (it carries a generous monetary prize as well as honour) opened doors for Fliter. ‘It was an amazing manifestation of trust towards my music-making.’

Ingrid Fliter grew up in a very musical family: her father was an accomplished amateur pianist, her mother would sing Puccini operas while bathing the children. It was an environment that fostered a love of music. So much so, that music was never a ‘choice’ for her. ‘From the very beginning music was part of my life and my being. This passion has nothing to do with pursuing a career or the world’s recognition, but with the conviction that it felt good and natural to express

Ch

RIS

TIA

N S

TEIN

ER born 1973, in Buenos aires

piano studies with elizabeth westerkamp in argentina before moving to europe in 1992 to study

made her debut as a recitalist at the age of 11 and as a concerto soloist in Buenos aires at 16

her big break receiving the 2006 Gilmore artist award – since then she has made important concerto and recital debuts throughout north america

beyond the solo piano repertoire she loves lieder, especially Schubert and Schumann, Bach passions, Beethoven and Mahler symphonies, Mozart operas, and playing chamber music

recordings show her affinity for the music of Beethoven and Chopin

in Australia australian debut

read more www.ingridfliter.com

further listening See More Music on page 41

Ingrid Fliter in conversation

In THe GReen RooM

25 | Sydney Symphony

Recording versus Recital?

‘I was never very attracted to studio recordings until I started recording for EMI. Good team work is fundamental and from that point of view I consider myself extremely lucky. Since my very first Cd, I discovered that recording in a studio opens the doors of exploration, development and expansion of your expressive possibilities. It gives you the opportunity to arrive nearer to your ideal, and to mature your relationship with the piece enormously. In any case, my approach has been always as if I was playing for the public, in order to keep the freshness and the essence of the music which I believe is emotion. The temptation to be a perfectionist is high though, so one has to be careful not to convert the recording into a laboratory experiment.’

myself through music, and I wanted to have it as my everyday companion.’

With her profound love of music comes a belief that bringing great music to people is not only a privilege but a mission. ‘A mission,’ she says, ‘because I think these creations give all of us an opportunity to live a better and more fulfilled existence. This is my engine – the reason I do what I do.’ The rest of it – the touring life in particular – can be less appealing: always on the go, the travelling, coping with jet lag, missing family and friends, and dealing with the ‘music business’. These are things one learns to live with, she says, ‘but which one could perfectly live without!’

One challenge is the piano’s lack of portability. Each destination brings with it a new instrument, sometimes (but not always) with the option of choosing between several pianos. ‘Sometimes it is love at first sight,’ she says, ‘sometimes it is hate at first sight! In any case, you learn to adapt and make the best of what you have. For me, a good quality of sound is fundamental…to sing better and to create a more intimate atmosphere.’

Singing and intimacy brings to mind Chopin. In her Sydney program Ingrid Fliter combines Chopin’s music with music by Beethoven – two very different personalities. ‘Beethoven has been a big love all my life,’ she says. ‘His music expresses this strong sense of will and struggle towards difficulties. He is an example for all of us. With him, music became a tool of expression for the soul, more than just a mere entertainment or a social event. Beethoven’s music embraces a transcendental comprehension and brotherhood towards the human nature.’

On the other hand, Fliter’s first musical memories relate to Chopin. ‘I remember hearing Arthur Rubinstein recordings everywhere: in the living room, in the kitchen, in the car, and my father playing waltzes. So I grew up loving Chopin’s music.’ As a student she learned the importance of a singing tone, thanks to Chopin. ‘Chopin in many aspects is essential and natural,’ she says. ‘This has led erroneously to the view of him as a “light” composer. Nothing could be further from the truth! I was very touched to discover his darker side, his sense of the tragic. He speaks directly to the heart; the story he tells us is deeply personal. His romanticism is not obvious and requires a strong sense of proportion.’ Perhaps the hardest thing is to achieve, she adds, is the balance between Chopin’s romantic soul and his classical expression. ‘But when I play Chopin I feel a warm wave of recognition among the audience. I believe he transcends matters of time or fashion and will always be loved.’

YVONNE FRINdlE, SYdNEY SYMPhONY ©2011

27 | Sydney Symphony

aBoUT THe MUSIC

Beethoven and Chopin

This program combines music by two of the greatest writers for the piano, who were also two of its greatest performers. Both composers wrote extensively for the instrument throughout their lives; both used the greater possibilities of the changing and strengthening keyboard to develop a range of technical innovations and a highly personal musical language.

However, each composer followed a very individual career path. Beethoven performed, conducted and composed over many years, writing great masterpieces in many idioms for many different instrumental combinations. Chopin played only in small salons after a few initial public concerts, and only wrote for the piano, with very few excursions into other areas. In their own ways they contributed a lasting testament to future generations, even down to present-day audiences and performers, who alike rejoice in their music.

Beethoven was known for his remarkable ability to improvise in public, sometimes in a competitive way, and on several occasions in variation form, in response to a given theme. This was a popular party trick, often requested of performers by emperors and music lovers.

He wrote down more than 20 sets of Variations, including some on operatic themes for cello and piano, the slow movement of his great ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata for violin and piano, and many sets for piano solo, including the ‘Diabelli’ and the ‘Eroica’ variations [to be heard in the next recital in this series].

The 32 Variations on an original theme in C minor were written in 1806, in one of Beethoven’s favourite keys for stormy emotional themes.

What is most needed for a set of variations is a strong and simple harmonic structure. In this set, the structure is very clearly heard in the left hand of the theme, as it descends note by note from C. At the same time the right hand gives us a series of proudly defiant melodic gestures in strongly dotted rhythm. Each of the variations is only eight bars long, which makes the whole work seem comparatively short: it often seems that one variation is over almost before it starts, as there are very few pauses between variations.

Beethoven uses the same bass line in the greater proportion of the variations, although he gives it a harmonic variation of its own from Nos. 5 to 8. In all of the first 11 variations, he refers to the right hand theme, but outlines it in different ways, sometimes as a skeleton under the skin, and sometimes as a more florid surface decoration.

Beethoven was known for his remarkable ability to improvise in public…

28 | Sydney Symphony

At the same time he varies and makes more complex the pianistic figurations, sometimes swapping them between the hands, in the style of a virtuoso juggling act.

From Variation 12 he takes us on a tour of five variations into the major key, where the emotional level is much less dramatic. Returning to the minor key for Nos. 17 to 31, he alternates fireworks with moments of reflection, still referring to his opening theme and harmony. And in No.31 he actually repeats the opening theme without any variation, but this time it is pianissimo as if heard distantly through a cloud. In Variation 32, he manages to sneak in three unnumbered variations, with an extensive ending that allows dominant and tonic to assert themselves strongly.

We have been given a splendid lesson in the technique of Variation writing, along with a rigorous pianistic workout!

The Sonata in e flat, op.31 no.3 was written in 1802, a year after the famous ‘Moonlight’ Sonata, at a time when Beethoven announced his intention to take new paths in his composition. Since the three Sonatas of Op.31 came just after the violin and piano sonatas of Op.30 and the three piano sonatas in Op. 27 and 28, all of which were remarkably

29 | Sydney Symphony

original in form and content, it could be said that he had already embarked on this path.

Contemporary comments suggest that these sonatas were considered a bit too long and rather bizarre – but then the two Sonatas of Op.27 (which included the ‘Moonlight Sonata’) were also considered to be beyond the understanding of the average music lover!

The Sonata puts together four unusual movements: the first has an ambiguous opening which presents a repeated question together with its sudden and contrasting answer, as the principal theme. There is no slow movement to follow, but rather a Scherzo whose two beats in a bar sound quite jazzy to our modern ears, particularly because of the accents on unexpected beats.

The next movement is a Menuett and the last one is a furious Tarantella. The key of E flat is a generally happy key for Beethoven: this Sonata is not a stormy one, but a set of four movements of delightful invention.

Chopin’s pianism and brilliant writing have always placed him at the forefront of pianist-composers. But it is probably his ability to turn the piano into a poetic instrument that is his lasting gift to musicians and audiences.

Always delicate in constitution and in performance, Chopin seems an unheroic Romantic figure, if one thinks of Liszt as the embodiment of Romantic pianism. Chopin expressed great enthusiasm for the music of operatic composers, such as Rossini and Bellini. He played Bach and Mozart, and recommended these composers to his students, and he was also interested in the music of contemporaries such as Hummel and Field. One would like to know whether he considered Beethoven to be as important as we do to-day. He is credited with playing only a few Beethoven Sonatas: he spoke highly of the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata (although he would not have known it by this title) and of the Sonata Op.26, with its Funeral March, which may have influenced his own ‘Funeral March’ Sonata. He is reported to have disliked the gigantic ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata when he heard it performed by Liszt.

As a performer he was most at home in private houses and salons, where he was renowned for playing his own works with an infinite range of expression, using a great variety of piano and pianissimo dynamics. He gradually withdrew from even these public performances in the 1830s, and devoted himself to teaching many titled, talented and wealthy students, whom he encouraged to play his works.

Contemporary comments suggest that these sonatas were considered a bit too long and rather bizarre…

30 | Sydney Symphony

Modern pianists, even two hundred years after his birth, still delight in the wondrous expressiveness of these works, so inextricably linked to the instrument he wrote for, and are considerably exercised to find that mastery of them demands great effort and perseverance! His pianistic writing is in fact the cornerstone of 19th- and 20th-century piano technique.

The title of nocturne was not Chopin’s invention. In style it is a song without words, and the singing voice in the right hand uses notes instead of words to communicate its meaning. Czerny said that they were an imitation of those vocal pieces called ‘serenades’. performed at night underneath the window of a loved one – which Mozart was also famous for writing. But Chopin’s 21 nocturnes with their inimitable melodic outpourings are completely distinctive. They sing of an unreal world and contribute to his own public image as someone not entirely of this world.

Much of his music is dominated by dance forms – mazurkas, waltzes, polonaises, forms that unite the Polish and French sides of his career – and the two sides of his nature as a Polish man living in France (the opposite of his

31 | Sydney Symphony

father who had moved from France to live in Poland). By the time Chopin was writing, waltzes had come to be

associated with the glitter and grace of Parisian salons and ballrooms, even if these ones for piano solo were unlikely to be danced. As a popular dance, the waltz had much more prosaic origins. The musical historian and traveller Charles Burney described the original waltz as ‘a riotous German dance of modern invention’. For many years before Chopin, they were a regular part of the repertoire of café bands and domestic salons, as well as ballrooms. The older generation considered them rather scandalous, because of the physical intimacy they encouraged between partners.

Chopin wrote his first waltzes while still living in Poland and continued the series ever more brilliantly in Paris. They are by turns scintillating and reflective, and many of them contain contrasting episodes of both these characters. Some of them, notably op.69 no.2 and the posthumous waltz in a minor are slow, and evoke a ballroom with only a few romantic couples still left. But others are extremely fast and make us all want to dance, although some of the tempos chosen would defeat those who tried. It is the pianist’s fingers that do the dancing!

Even the Ballade in F minor has more than a suggestion of a waltz-like rhythm, in its elegiac opening sequence. The use of the word Ballade in a musical context seems to have been largely invented by Chopin himself, and he understood by it a title without a definite program, but with a distinctly narrative style. Ballads in song and poetry often tell a story on an epic scale; poetic versions often celebrate folk sagas and are often written in strongly metrical forms which emphasize such roots.

The Ballade in F minor is the last of four he wrote in this form and it is undoubtedly one of his greatest works. It explores two main themes which he develops and varies in poetic ways and with increasing drama. The final two pages of coda are intense and cathartic in their effect. The listener is conscious of having been told a narrative of great importance and soul-searching intensity, but one which would be difficult to repeat in words. Perhaps this quality is what is most distinctive in Chopin’s music: the ability to speak profoundly through the medium of the keyboard, and to communicate deeply and directly to each individual listener without resorting to words. No other composer for the piano did this better.

STEPhEN MCINTYRE ©2011

‘a riotous German dance of modern invention’CHARLES BuRNEy

C

M

Y

CM

MY

CY

CMY

K

sydneySymphony_kambly.2_OT_PQNE.pdf 1 28/01/11 12:07 PM

05TH-E-G S12-14 Mahler6.indd 10 25/02/11 8:16 AM

33 | Sydney Symphony

2011 SeaSon

InTeRnaTIonaL PIanISTS In ReCITaL PReSenTeD BY THeMe & VaRIaTIonS

Monday 1 august | 7pm City Recital Hall angel Place

FReDDY KeMPF In ReCITaL

LUDwIG Van BeeTHoVen (1770–1827)

15 Variations and Fugue on an original Theme in e flat, op.35 (eroica Variations)

Piano Sonata no.21 in C, op.53 (waldstein)Allegro con brio Introduzione (Adagio molto) – Rondo (Allegretto moderato – Prestissimo)

InTeRVaL

GIoaCHIno RoSSInI (1792–1868) arranged LISZT

La Danza – Tarantella napolitana(from Soirées musicales de Rossini, S424)

FRanZ LISZT (1811–1886)

Petrarch Sonnet no.104 (from Years of Pilgrimage II: Italy, S161)

LISZT after GaeTano DonIZeTTI (1797–1848)

Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor, S397

LISZT after woLFGanG aMaDeUS MoZaRT (1756–1791)

Réminiscences de Don Juan, S418

This concert will be recorded for later broadcast on ABC Classic FM.

Pre-concert talk by dr Robert Curry at 6.15pm in the First Floor Reception Room.

Visit sydneysymphony.com/talk-bios for speaker biographies.

Estimated durations: 13 minutes, 26 minutes, 20-minute interval, 4 minutes, 7 minutes, 6 minutes, 20 minutes

The concert will conclude at approximately 8.50pm.

presenting partner

C

M

Y

CM

MY

CY

CMY

K

sydneySymphony_kambly.2_OT_PQNE.pdf 1 28/01/11 12:07 PM

05TH-E-G S12-14 Mahler6.indd 10 25/02/11 8:16 AM

34 | Sydney Symphony

In 1981 John McEnroe finally won Wimbledon. Freddy Kempf became crazy about tennis. Next, the Formula 1 season put British driver Nigell Mansell in the news. Freddy wanted to be a driver. Then his parents took him to the toy shop to choose what Father Christmas would bring him. Influenced more by the impressive price tag than anything else, Freddy settled on an electric keyboard. On Christmas Day it was his only present.

He began by teaching himself, playing the songs he knew from Disney soundtracks. ‘Then I wanted to learn properly,’ says Kempf, ‘and it all went on from there. But you could say it was almost by accident that I became a pianist. The piano was the first thing my parents said “Yes, you can try that if you want” – because it wasn’t as unrealistic as motor racing or tennis.’

Kempf counts his teachers among the biggest influences in his life. ‘My first main teacher – who taught me from six till fourteen – he really gave me my hands, he gave me the way I play. I was with him for such a long time and at such an early age that I won’t ever forget him.’ The teacher was Ronald Smith, who’d been a student of Marguerite Long and Pierre Kostanoff.

His last teacher, Emmanuil Monaszon, worked with him from the age of 19 to 21. ‘He found that I was a Romantic at heart, and he managed to push away those insecurities that I had: just wanting to show everyone how fast I could play or how technically accomplished I was. He made me focus on the emotional side of my playing. It was hard for a person in

MO

NIq

uE

dEu

l born 1977 in London, to a German father and Japanese mother

he is related to pianist wilhelm Kempff

also plays violin and harmonica

can speak english, German, Russian and French, a little Japanese, Italian and Spanish, and a smattering of eight other languages including arabic

first big break won the BBC Young Musician of the Year Competition performing Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in 1992

became a ‘hero’ with Russian audiences when he received third prize in the 1998 Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow – they thought he should have won!

current project this season he will perform all the Beethoven piano concertos directing the Royal Philharmonic orchestra from the keyboard

recordings include Prokofiev piano concertos

in Australia he has performed with the Tasmanian, adelaide and Queensland symphony orchestras; this is his Sydney Symphony debut

read more www.freddy-kempf.com

further listening See More Music on page 41

Freddy Kempf in conversation

In THe GReen RooM

35 | Sydney Symphony

Liszt the percussionist

‘liszt was very adventurous with what the piano was capable of at the time and he wasn’t afraid to take risks,’ says kempf. ‘The piano is a percussion instrument – a thrown lever with no actual direct connection between the finger and the hammer. So the only thing you can affect on the piano is the speed at which the hammer hits the string, which means the only thing you can affect is the volume. The only leeway you physically have is to control the balance between different notes, and I think liszt was one of the first to really explore that.’

their late teens to adjust to that, but he was Russian, so he was probably more assertive than your average non-Russian teacher. He changed my playing the most, even though I didn’t study with him for very long. It’s enabled me to be much freer about my choice of repertoire; I’m not trying to prove something. Basically I can play whatever I’ve wanted to play, and whatever has interested me.’

Which is not to say that the repertoire that interests Kempf isn’t virtuoso music of the highest order, as his Sydney program demonstrates. It’s been influenced in part by the bicentenary celebrations of Liszt’s birth in 1811. Elsewhere in the world this year he is performing an all-Liszt program. That selection has formed the basis for what he will play in Sydney.

In choosing Beethoven for the first half, he explains, he’s opted for works which ‘sound as if they would be familiar, but which are probably less familiar than, say, the Pathétique Sonata or the Appassionata.’ Even more important is the experimental side of Beethoven these two works reveal. ‘Both have very unusual pianistic effects, pioneering for the time,’ he say. ‘I’m thinking of the end of the Waldstein, where he marks for the pedal to be held down to create this aura of sound.’ The Eroica Variations is remarkable for its technical challenges too. ‘Before Beethoven, a composer wasn’t expecting the performer to really practise – but with the Eroica Variations there is no way anyone could just sit down and sightread it. It takes a lot of work, and that in itself was a new thing.’

Most striking in Kempf ’s Liszt selections is that only one work, the Petrarch Sonnet, is original. The rest show Liszt wearing his transcriber’s hat, from Rossini’s tarantella, La Danza, to the monumental Réminiscences de Don Juan – ‘one of the craziest, most difficult, ostentatious works of Liszt you’re ever likely to find.’ Kempf is fascinated by the 19th-century practice of transcription and the way such pieces, especially transcriptions of opera, not only brought music to a wider audience but functioned almost as trailers for the complete work. Playing these transcriptions has given him an appreciation for Liszt’s knack for making the piano sound like an orchestra.

Beethoven and Liszt – both risk-takers and pushing musical and technical boundaries. And, as Kempf points out, ‘they were both pianist-composers who used their solo careers to push their composing careers and vice versa. That is important, because you have to think that they were writing for themselves. They were writing music that they would be performing in concert. Which is why they could push those boundaries.’

YVONNE FRINdlE, SYdNEY SYMPhONY ©2011

36 | Sydney Symphony

aBoUT THe MUSIC

Heroes and Myths

As this concert begins with Beethoven’s ‘eroica’ Variations, it may be pertinent to ask: exactly what makes a hero? The question certainly puzzled the composer in 1804, when news reached him that Napoleon had proclaimed himself Emperor. He angrily defaced the cover page of his Third Symphony – originally to be dedicated to the man he had held in high esteem, and titled ‘Bonaparte’ – inscribing instead a qualification: ‘Heroic Symphony, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.’ The manuscript of the present work, the so-called ‘Eroica’ Variations for piano, coincidentally conveys a similar change of thought on its title page, albeit for different reasons. Ultimately, the work was published in 1802 simply as ‘Variations’ and, being one of his first in the genre to be given an opus number, the composer requested specifically that his publishers advertise its originality.

And original it is, beginning not with the theme but with the merest suggestion of its accompaniment, the inexplicable gaps presenting something of a riddle. A second voice is added, then a third and a fourth, until at last the melody is heard in full. Not all is new, however, as the idea of gradually revealing the theme stems from the context of its similar use in his earlier ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus. As a further innovation, the ensuing variations are followed by a seemingly conclusive fugue, which leads not to the work’s end but to a diverting Andante con moto. Ultimately, it was the employment of the material two years later in the finale of the ‘Eroica’ Symphony that gave these variations their name;

The Incident at Teplitz — Goethe bows, Beethoven strides on (Carl Röhling, c.1887)

37 | Sydney Symphony

when they first appeared, an astute listener would have likely called them the ‘Prometheus’ variations.

As with the symphony, the question of what makes a hero was a pivotal one to the generations of composers that followed. Within two decade of the composer’s death, what some have termed the ‘Beethoven myth’ had begun, an early example of which is Joseph Danhauser’s painting Franz Liszt fantasising at the piano (1840). Here, an oversized bust dominates the canvas, placed as if on an altar, and while the audience is transfixed by the piano playing of Liszt, it is at the majestic image of Beethoven that he intently stares. Evoking immortality, proscenium-like curtains depict the composer in an exterior world, his stony visage framed by dark clouds.

Precisely why Beethoven was transformed into an heroic figure so rapidly remains a matter of conjecture. To many, it rests solely on his music, its innovations paralleling emergent Romantic themes. Yet, partly, it also reflects interpretations and presumptions of an eccentric and uncompromising personality. Anecdotes have fed the mythology, such as one from Teplitz in 1812, where Johann von Goethe and Beethoven strolled together in a park: encountering the Empress of Austria, Goethe made a respectful low bow as Beethoven rudely strode past, intentionally snubbing her. Nor did Beethoven exactly square with notions of professional service, happily refusing a formal appointment in Kassel after three patrons – the Archduke Rudolph and Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky – sponsored a substantial annuity. The notion of ‘the artist as an individual’, a crucial theme of the age, was thus firmly

Franz Liszt fantasising at the piano (painting by Josef Danhauser, 1840). This imaginery scene shows (seated) alexandre Dumas, père, George Sand, Franz Liszt at the piano and Marie d’agoult; with (standing) Victor Hugo, niccolò Paganini and Gioachino Rossini. a bust of Beethoven stands on the Graf piano.

©A

kG

-IMA

GES

38 | Sydney Symphony

established. Beethoven’s steadfast confidence had been fostered in early years by Count Ferdinand von Waldstein, who had encouraged him at the age of 16 to seek lessons with Mozart. Perhaps engendering further a sense of worthiness, when Beethoven left Bonn in 1792 Waldstein famously wrote to him ‘may you receive the spirit of Mozart through the hands of Haydn’.

The ‘waldstein’ Sonata, published in 1805, is from what has become known as Beethoven’s heroic period. Stylistic hallmarks of these compositions include themes created not so much from melodies but from ideas, as with the opening subject: the harmonic direction and transposed motivic echoes seem perhaps less significant than the energetic, pulsating rhythm. Typical, also, is an epic quality, formed as much by conspicuous virtuosity as by evocations of space, as in the slow movement, Adagio molto. This serves as an introduction to the finale, the opening of which appears (like the dawn, as some have noted) over a cushion of glistening arpeggios. Like Beethoven, Count Waldstein viewed Napoleon’s ambitions as a threat, devoting much of his later life (and most of his wealth) to the creation of an army. It is possible that around the time of writing the sonata, Beethoven was aware of Waldstein’s brief return to Vienna (incognito, so as to evade his creditors!).

Despite its romantic appeal, Danhauser’s painting is a contrivance as the assembled characters never met together at the same time. Yet it still offers valuable insights into the period. At Liszt’s feet is the Countess Marie d’Agoult, his lover and the future mother of his children, while seated to the left are the authors George Sand (pen-name of Baroness Dudevant, née Aurore Dupin, the later friend and confidant of Frédéric Chopin) and Alexandre Dumas, père. The revolutionary literary giant, Victor Hugo, stands resolutely behind, and to his right is Italian violinist and composer, Niccolò Paganini. The remaining member of the group, however, now seems out of place: at the time, Gioachino Rossini was the most well-known of living composers, yet in terms of the trajectory of the Romantic age – and, in particular, its lineage from Beethoven – his was music of a different sphere.

Rossini ‘retired’ at the height of his fame at the age of 38 with a similar number of operas under his belt, and his collection of 12 solo songs and duets that make up the Soirées musicales, published in 1835, is one of the more significant works of his later years. (As his expansive girth in the painting indicates, he settled on a life as an amateur chef and gourmand.) La danza is in the style of a Neapolitan patter-song to a light-hearted text by Carlo Pepoli, and is the eighth

In retirement, Rossini settled on life as an amateur chef and gourmand (1865)

39 | Sydney Symphony

in the set. As with the companion works in the collection, Liszt faithfully adopts Rossini’s simple piano introduction, yet demands a fiendish degree of technical proficiency when the vocal line joins in.

Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) was an artistic hero of an earlier age. On the topic of love, his monumental collection of poetry, Il canzoniere, is revered as a treasure of the early Renaissance. Within the anthology are more than three hundred sonnets addressed to Laura, a character viewed from afar. Liszt set three of these for high voice in 1839, publishing piano arrangements in 1845 and the more widely known revisions in 1855. In the later version of Sonetto del Petrarca 104, the introduction truncates the first four recitative- like lines of the song, the famous melody commencing on the words ‘Love has me in a prison.’ The central musical idea – a short, descending phrase set over harmonically ambiguous ‘augmented’ chords – recurs at ever increased levels of intensity, before a more resolute tone is reached on the final line. As a coda, Liszt gently recalls the undulating harmony, repeating (and augmenting) Petrarca’s text.

The sextet from the second act of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor marks the crucial point when Lucia’s ill-fated life comes irreversibly undone. Having accepted the ring of Edgardo, her beloved, she has been cruelly deceived about his intentions and compelled to accept the hand of another. As the contract is signed, Edgardo returns and, heartbroken with grief, tears his ring from her hand. The complex conflict of emotions is aptly conveyed by Donizetti, adding voices in layers until all six sing together. Liszt preserves the essential fabric of the music, the melodic lines unadorned save for cadenzas at two climactic points. The return to the opening accompaniment pattern at the conclusion is, sadly, not of Liszt’s choosing: originally, the keyboard fantasy was to move to the funeral march and cavatina from the finale, providing a contextual reference for the sextet. Yet as a novice in his late 20s, he had little option but to divide the work in two to address the publisher’s concern over length. The title – ‘Réminiscences’ – perhaps better relates his original conception of the work.

It is freely acknowledged that Réminiscenses de Don Juan is Liszt’s greatest operatic fantasy. Far from being a loose collection of highlights from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, it is a tautly conceived work conveying the essence of the drama. As Mozart had done in the overture, Liszt begins with music from the conclusion, although here it is the Commendatore’s grim threat from the graveyard: ‘your laughter will be silenced before morning.’ The harmonically

40 | Sydney Symphony