544 project final

-

Upload

anthony-zambella -

Category

Documents

-

view

83 -

download

0

Transcript of 544 project final

IntroductionThis experiment was aimed at observing the flee responses in the Black-Capped Chickadee

(Poecile atricapillus) and the Tufted Titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) when exposed to a native bird of prey (Cooper’s Hawk, Accipiter cooperii), as well as a non-native bird of prey (Red Footed Falcon, Falco vesterrinus).

Due to the fact that neither the Black-Capped Chickadee nor the Tufted Titmouse have never been exposed to the call of the Red-Footed Falcon, it is predicted that the two studied species will flee in response to the call of the Cooper’s Hawk more frequently than that of the Red-Footed Falcon.

Materials and methods

The experiment was performed in Georgetown Massachusetts, about 40 minutes north of Boston. Four tube feeders were used, spaced 10 feet apart from each other and supplied with black oil sunflower seeds. The speakers used for the experiment were two JBL JRX115 15-inch 250 watt two-way loudspeakers, which were positioned 30 feet away from the feeders.

Observations were taken over ten days between the months of February and April of 2015. Both The Cooper’s Hawk and Red-Footed Falcon call were played 10 times in the morning and 10 times in the afternoon to rule out time of day as a variable. Calls were played for a duration of 30 seconds followed by a 10 minute assessment of the area using binoculars.

Results

Of the 20 total times recorded, the Black-Capped Chickadee was seen at the feeder 20 times and the Tufted Titmouse was seen a total of 16 times. The Black-Capped Chickadee fled from the Cooper’s Hawk call a total of 8 out of 10 possible times. Of the 8 possible times, the Tufted Titmouse fled a total of 6 times (the 2 times the stimulus was ignored was also while it was observed at the feeders with the Black-Capped Chickadee.) When the birds fled from the Accipiter cooperii call, the average time to return to the feeders was about seven minutes, however sometimes neither the Black-Capped Chickadee nor the Tufted Titmouse would return at all for the rest of the afternoon.

Data Table:

Conclusions

Based on the data collected from the twenty recordings, regarding the (Coopers hawk), It can be safely concluded that there is some correlation between bird of prey calls and the triggering of a flight response in the Black Capped Chickadee and Tufted Titmouse. With regards to the Red-Footed Falcon, the species that is not seen in North America, there was a general trend showing that the auditory stimulus of their call alone did not elicit a flight response in the Black Capped Chickadee nor the Tufted Titmouse. The most likely reason for this result is that the Black Capped Chickadee nor the Tufted titmouse have not been exposed to the Red-Footed Falcon or its vocalizations, and as such do not pick the call up as a stimulus that a predator is in close proximity. Another possible (though unlikely) reason for this result is that the call was either too soft or too loud, thus confusing the birds or resulting in them ‘drowning’ out the noise and not picking it up as an avian vocalization.

It is interesting to note that, although the Black Capped Chickadee nor the Tufted Titmouse responded much to the call of Falco vesterrinus, when they did respond to it they both fled from the feeders, suggesting that there is a possibility that they confused the call with another bird of prey species endemic to North America.

Anthony Zambella

Literature utilized in research

1. Dooling, Robert J.; Brown, Susan D.; Klump, Georg M.; Okanoya, Kazuo. Auditory perception of conspecific and heterospecific vocalizations in birds: Evidence for special processes.Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol 106(1), Mar 1992, 20-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.106.1.20

2. Schaef, KM et al. Predator Vocalizations Alter Parental Return Times at Nests of the Hooded Warbler. Nov 2012.

3. MacLean, Sara H and Bonter, David N. The Sound of Danger: Threat Sensitivity to Predator Vocalizations, Alarm Calls and Novelty in Gulls. 6 Dec 2013.http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0082384

4. Yorzinski, Jessica L. and Patricelli, Gail L. Birds Adjust Acoustic Directionality to Beam their Antipredator Calls and Conspecifics. The Royal Society. 2009. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2009/11/18/rspb.2009.1519

5. Schaef, KM et al. Predator Vocalizations Alter Parental Return Times at Nests of the Hooded Warbler. Nov 2012. http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=5&SID=3D7M1VV9UXBwMeTDqlI&page=6&doc=53

6. Ellis-Felege, SN et al. Fight or Flight: Parental Decisions about Predators At Nests of Northern Bobwhites. American Ornithologists Union. 2013; 130(4): 637-644. http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=5&SID=3D7M1VV9UXBwMeTDqlI&page=3&doc=29

Do passerine birds respond to calls of a non-native bird of prey? Flee response in Poecile atricapillus and Baeolophus bicolor

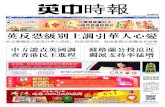

Figure 2: Flight responses observed in Poecile atricapillus and Baeolophus bicolor

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2015