50 - michaelbradydesign.com files... · Design Management Peter Dewes, P.E., STV Inc. Donald...

Transcript of 50 - michaelbradydesign.com files... · Design Management Peter Dewes, P.E., STV Inc. Donald...

50

5151

Introduction

What is a megaproject?First, mega. What is “mega”? In the context of the design and construction industry

this term is usually applied to a project that is complex, that takes many years to de-velop and construct, operates for many years, and costs billions of dollars.

Second, project. What is a “project”? When one looks at, say, a railway line, one sees trains, stations, tunnels, bridges, embankments, cuttings, yards, shops, many staff op-erating and maintaining the system, tracks, signaling and control systems, electrical systems, communications systems, access paths and roads, parking facilities, bus stops, taxi drop-offs, and, last but not least, passengers or freight. If any element of the line is missing, then the railway may not work! If it is made too small, it may be illegal. If it cannot cope with passenger increases over a period of 50 years, then it may become unsafe. It should probably be functional for more than 100 years, and some projects are even older than that. A megaproject is all of these very visible things and the various tools and techniques required to plan, design, construct, operate, and maintain them.

Who participates in a megaproject?First, the owner, who owns, usually operates, and maintains the project; second, the

stakeholders, who are the various neighbors living near the project or others who can be influenced by it; third, the designers, who plan and design the project; fourth, the con-tractors, who construct the project; fifth, the operator and maintainer, who performs the daily operations and maintenance of the project; and finally, the customers, who use the project or obtain a service from it. Each of these participants eventually becomes involved in the design of the project. For a megaproject, that number can reach into the hundreds of thousands! Who are they? Consider a subway in Manhattan running along the East Side from Harlem to Wall Street. It will affect most of the inhabitants of Man-hattan, the rest of New York City, many people in the state of New York, and, if funding and material procurement is considered, many inhabitants of the United States.

CHAPTER 4

Design ManagementPeter Dewes, P.E., STV Inc.Donald Phillips, P.E., Arup

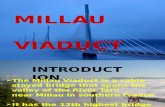

The Millau Viaduct, at left, crosses the Tarn River Valley near the town of Millau in south central France. Designed by Norman Foster and Partners and built by the Compagnie Eiffage consortium (Eiffage, Eiffel, and Enerpac), the bridge is 8,000 feet long, has 7 pylons, and is 886 feet above the ground at its highest clearance. It was opened to the public in December 2004. Photo 2006 by Vincent.

5252

Design is a fundamental part of all megaprojects. Design takes the initial idea or con-cept of a megaproject and, through many iterative steps, delivers drawings, specifica-tions, and construction sequences that individually shape the result. Design turns ideas into reality. Design is a key communicator of the project’s intent and as such must in-teract carefully with all the project participants and work with the existing infrastruc-ture that will contain the project. Approval and acceptance of the project by the various stakeholders is also achieved by the owners and designers through the design process.

Design is not a simple mechanistic process. Rather, it is iterative and holistic, and, to achieve good results, it must incorporate all the requirements of the project and work with all of the various teams in the process. Ove Arup once noted, “Engineering prob-lems are under-defined; there are many solutions, good, bad and indifferent. The art is to arrive at a good solution. This is a creative activity, involving imagination, intuition and deliberate choice.”

We have but one chance to complete the design of a megaproject. Then it is with us for all of our lives and our children’s — sometimes longer — be it “good, bad or indiffer-ent.” Whatever we do will be our legacy. As Winston Churchill said, “We shape our build-ings; thereafter, they shape us.”

This chapter will take the reader through the design process for a megaproject.

Design Phases

The design for a megaproject should proceed in an iterative manner to allow suffi-cient information to be made available sequentially, to obtain key approvals and fund-ing, and to accomplish other key objectives. It is not possible to complete the design in one single phase, as a number of associated tasks must be accomplished to give cer-tainty to the project. Each design phase has a key objective, and as time passes and the project becomes more clearly understood, it can be defined more accurately. Typically, the phases of a megaproject are:

• Feasibility study• Project definition• Environmental impact statement• Preliminary design• Final design• Contract document preparation• Construction and commissioning• As-built/operation and maintenance manuals• Operation and maintenance of the megaproject

As with any process, risks and opportunities exist at each phase until the project is com-

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

5353

plete and successfully operational. As the project advances, it is critical that these risks and opportunities be recorded and then sequentially and proactively managed and mitigated.

The project’s design will continue to advance and develop throughout each phase, which will call for appropriate contingencies for cost, time, investigations, and the need to reas-sess and amend the design. Project functionality may also vary during the design process as the actual cost and implications of certain project aspects become better defined.

Design and engineering are not exact sciences, so that a good deal of understand-ing and some latitude in application is necessary to achieve an acceptable outcome. Ad-dressing the British Institution of Structural Engineers in 1976, A. R. Dykes observed, “Engineering is the art of modeling materials we do not wholly understand, into shapes we cannot precisely analyze, so as to withstand forces we cannot properly assess, in such a way that the public has no reason to suspect the extent of our ignorance.”

Feasibility Study

This phase establishes the technical feasibility of a project, defines the likely cost and time scales, and gives a reasonable indication of the project’s form, alignment, and key elements, which allow its interaction with the adjacent land and usage to be com-prehended. It is possible that at the end of this phase, several solutions to the proj-ect may exist, so that additional phases might be needed to narrow the options under consideration.

At the end of this phase, the feasibility of the project should be determined, with costs and time ranges calculated and accepted as reasonable.

Project Definition

Megaprojects are so complex that the mere definition of one may take several inches of paper to properly summarize. During this phase, the project will be described in suf-ficient detail to allow the operational performance of the project to be defined, under-stood, and approved. This is also the phase when the owner will be able to determine whether the project will render the requisite performance for the investment required to construct the megaproject. (That is, will the performance, income, and other benefits from the project exceed its costs?)

Project definition and design should proceed in parallel in order to describe the project properly. Before the final design commences, the project should be defined in terms of:

• Project objectives• Service requirements• Functional requirements

chapter 4 | Design Management

5454

• Fire safety strategies• Previously approved design report• Environmental impact statement and stakeholder requirements• Land requirements• Impacts upon existing infrastructure and solutions that allow the project to be

implemented• Property development interface reports• Project schedule• Project cost estimate and finance plan• Design criteria, including national and local codes and standards• Standard spatial requirements• Standard specifications• Standard details• Standard schedules• Guidance notes• Drawing and CADD manual• General system assurance requirements

The owner’s specific requirements for the operations, maintainability, system safety, reliability, and testing and commissioning should be included in the various project def-inition documents. Similarly, stakeholders’ requirements that will impact the project should also be included.

The project definition phase may become part of the feasibility phase or the EIS phase, which comes later. But because it is so important, it is noted here separately to emphasize the function of this phase.

Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)

In the United States, projects seeking federal government funding are usually re-quired to complete an environmental impact statement (EIS). In many other parts of the world similar assessment processes are required to obtain governmental approval and support for megaprojects

Typically, the EIS is divided into “Draft” and “Final” subsections and creates a project definition that conforms to federal, state, and city government planning processes. The larger the scope of the project, the larger the planning process becomes and the more extensive the interaction with stakeholders, which increases the detailed investigation into the project. By the nature of the EIS process, many good ideas surface to form alter-native options, which can relate to potentially all aspects of the project. Although these alternate ideas will not be designed in detail, they will be studied sufficiently to assess

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

5555

them. They can cover the range of environmental topics, such as impacts to wetlands, flood plains, surface water, benthos, noise, air quality, traffic disruption, utility demand, habitat, etc. The EIS process also examines the contamination of the impact corridor, the impact on the contaminated sites by the project, and the impact on the project by the contaminated sites. The alternates are evaluated for their ability to achieve the proj-ect’s objectives and for their cost and time requirements.

Each alternate is evaluated against a set of criteria and ranked from the best to the least attractive. The best alternate is usually taken forward to the next phase for further development.

Since the process is ongoing and many stakeholders have input into it, the project definition will be continuously revised throughout the EIS phase and modified to negate or mitigate the impacts determined to be of concern. This has been the typical routine through many different projects of the “mega” class. For highway and railway projects, de-fining each alternate usually takes the form of an alignment change, though these changes often include many other subtle and distinct differences that may significantly impact each alternate’s cost, time, and functional performance. Such changes occur for many rea-sons, from improvements to the roadbed alignment and increased speed, to reduced cur-vature and a more comfortable ride or a reduction in land acquisition, lessened impact upon adjacent structures, lowered cost, and shortened time to complete the project.

Preliminary Design (PD)

The preliminary design (PD) phase is the first phase of designing the project, as de-fined in the original concept. By the completion of the EIS phase, many risks and oppor-tunities will have been identified that will need to be reviewed and assessed. Also at this time, when the preferred modifications are chosen, it will be necessary to commence site investigations and surveys to define or confirm the various assumptions that may have been made in the earlier project phases.

Based on various site and other data, the PD will usually include peer reviews, value engineering recommendations, or constructability reviews of the schemes to minimize the risks and maximize the opportunities previously identified.

As the EIS process comes to a close, the preliminary design phase begins. The start of the PD phase and the end of the EIS phase usually overlap. For the project, this is good, but for those performing either the EIS or preliminary design, it is a mixed bless-ing. Why? The EIS team members have usually been working on the project for many months — in some cases, years — developing what they believe is the perfect project. They have identified and assessed, and then tweaked, all the possibilities and, through a long and arduous process, they have finally produced a project definition that meets all criteria and is agreeable to the myriad of stakeholders. And now . . . a new group of

chapter 4 | Design Management

5656

designers is invited to join them. At this point in its life, the project trades planners for engineers. (There will be one more hand-off with the same trepidation, when the project exchanges engineers for construction teams.)

The engineers are usually obliged, as their first task during the PD phase, to verify the existing design and the cost estimate. This is a moment when the direction of the proj-ect can be changed. The first step is to develop the project definition documents. These criteria increase exponentially from EIS to PD to FD (final design) phases of the project as more detailed design assessments are able to be undertaken. Whatever happened to the EIS design criteria? Most of the time, these criteria become the higher-level crite-ria, service requirements, and functional requirements. In the PD phase, more detailed criteria are developed, which more precisely define the project and result in greater cer-tainty in the design. PD phase criteria and designs may not continue into the FD. And if the EIS phase used the details of the PD phase, the EIS process would never be com-pleted and the costs of the EIS phase could grow beyond reason.

At first, the PD task of verifying the design and cost may seem to ignore the environ-mental requirements, with alignments being examined in detail, additional site inves-tigations being undertaken to define topographic conditions and restraints, and subse-quently designs and costs being re-examined using the new data. The consequences, for example, could result in a roadway alignment that might change the route of the project to a slightly different zone, which would affect slightly different properties with slightly different environmental impacts. The rock elevation may be found in the PD phase to be lower than in the EIS phase, so tunnels would be moved deeper and surface projects would require deeper foundations. And then, through the constructability review pro-cess, additional cost impacts might be uncovered, which then require value engineering and revisions to the design to bring costs back in line with the project budgets.

By the end of the PD process, the project would have changed and a revised project definition would have been created. Because the EIS and PD processes are developed concurrently, the EIS would then adopt the new project definition. Impacts would be weighed against it and refined criteria developed during the public process. On occasion, the EIS team might be able to accept the revised project definition, but generally, only some of the proposals will be accepted, so another project definition would be developed.

At this point in the project timeline, three or four project definitions will have been established, not counting the alternatives that never saw the light of day. And we are not finished with the potential for yet more revised definitions. Each time an amended project definition is accepted, it is published in a public document so stakeholders can be aware of it and consider its impact upon their facility or structure. In our experience on three other megaprojects, no two went through the same process and changes.

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

5757

Final Design (FD)

The final design (FD) phase continues to develop the PD scheme so that the construc-tion documentation can be prepared and the cost estimates carefully and critically re-viewed and finalized, together with detailed construction schedules and contract pro-curement packaging. During this phase, further site investigation and advanced utility investigations will be undertaken, if required.

Of course, the PD scheme will require more changes to incorporate all the require-ments of the EIS and project definition and to satisfy the new and likely changed data submitted from the various detailed investigations.

Further, as the design is developed and finalized, it may be determined that some areas of the project require further amendment, which will have an impact on the scheme, its cost, and potentially its functionality.

All aspects of the PD scheme may change, and the owner needs to be informed of re-quired changes. The means of procuring the contract (i.e., in terms of contracting strat-egies, contract packages, and size and scope of each contract) should be decided upon with sufficient lead time to prepare proper documents and to avoid any incorrect defini-tion of the various contract packages, particularly the critical interfaces between these contracts.

Under the design-bid-build means of procurement, the owner engages a designer to complete the design, and once that is done, the owner seeks bids from contractors who then construct the works. Under this procurement approach some elements of the design are completed by the contractor, such as reinforcement details, steelwork con-nections details, and temporary works. There are other means of design and construc-tion procurement, such as design-build, design-build-operate, and design-build operate- finance. Each of these procurement types subtly adjusts the requirements of the design, design phasing, and schedule.

Contract Document Preparation

To prepare the contract documents, details of the contract size, type, work sites, con-struction means, electrical power requirements for construction, road and railway di-versions, utility diversions, and structure repairs and removal must be specified to ac-curately define the construction works. As these details become known, the design may need to change. Adequate time and flexibility will be required to complete the work.

Construction

Not all projects require the design to be complete before construction contracts are let, but if this approach is followed, then the FD documents must include adequate in-

chapter 4 | Design Management

5858

formation to obtain competent bids and, of course, include adequate contingencies to allow some design development to occur.

The contractor’s means and methods and temporary works themselves will often require significant further design, and in some cases they will impact the permanent works, thus necessitating adjustments to the project’s otherwise complete final designs.

Projects that include vehicle procurement and other complex equipment may require sophisticated testing and commissioning to provide systems that achieve the required levels of performance, safety, reliability, and maintainability. If a system safety assur-ance scheme is required, this will call for significant efforts to develop the appropriate framework, contract obligations, and collation of the specified documentation.

As-Built Drawings, Operation Documents, and Maintenance Manuals

As the construction proceeds, as-built drawings need to be produced which either confirm that the works have been constructed in accordance with the original design documents or show where deviations from them have occurred. The designer will then need to assess these deviations and confirm or make changes to the design.

All the operation and maintenance manuals are produced at this time, using technical data from the actual equipment that is used in the works.

Design Process

Approvals

The approval process for a megaproject is long and one that continuously impacts the design. Achieving project approval requires the concurrence of many stakeholders, profes-sionals, and the general public, the people who will use the project when it is finally com-pleted and operating. The design professionals may believe they have the right answer, but that depends on whether the project is used once it is operating. For all the great ideas and design that created it, a megaproject (mega not only because of the costs, but also because of the size of the population touched by the project) must be used by the mega-population, which accounts for the large number of parties involved in the approval process. The proj-ect’s design is guided by these parties outside the design professionals.

Generally, for rail transit projects in the United States, the Federal Transit Administra-tion (FTA) approval process remains open during the preliminary design phase. As the PD advances, modifications continue to be made to the design, which in turn require modifi-cations to be made part of the FTA approval process. The project schedule may be short-ened by the concurrent advancement of both the FTA approval process and PD, which will cause the coordination between the two phases of project development to be increased.

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

5959

After the FTA approval process, the more arduous process of federal, state, and local permits begins. A significant proportion of megaproject approvals involves environmen-tal and code compliance. The environmental approval process involves the U.S. Environ-mental Protection Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, and state environmental de-partments, agencies, and commissions, which have jurisdiction over construction within regulated environs. In the New York metropolitan area, for example, megaprojects can be located in flood plains, wetlands, riparian lands, tidal areas, or brownfield sites, all of which require permits and public review processes before approvals can be secured.

In addition to the environmental approvals, building code compliance is also required. Although some of the agencies sponsoring megaprojects are self-certifying, not all are, and approvals from the “authority having jurisdiction” (AHJ) is required. Depending on the type of construction (e.g., stations, tunnels, underground occupied space, high-rise development, foundations, and utility services), the code review process is varied and can be extensive. Since the code review process comes at the end of design, coordination with the AHJ during the development of the megaproject is recommended. Although early coordination can prove beneficial to the approval process and ultimately the sched-ule, many owner agencies are reluctant to schedule early coordination meetings with the AHJ because it gives the AHJ too many opportunities to impact the design, which usu-ally has an effect on the budget or schedule. However, last-minute requirements by the AHJ can have a greater impact on the schedule due to redesigns. Redesigns at the end of the process are not usually met with the same enthusiasm as during the design develop-ment phase because the changes must be made quickly, without the luxury of time for integration due to the impending need to bid the construction packages.

A well-planned schedule, with contingencies for the agency approval process and schedule impacts, can reduce delays caused by an extended approval process or design modifications to comply with the approving agency’s requirements.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders are people having a vested interest in the outcome of the project. They may not be professionals in the design field, but they can be users of the project. The quip, “I may not know what art is, but I know what I like,” applies to the design and development of megaprojects. Through public meetings, comments, and hearings, the designers learn what the public want. On transportation projects, where the people want to go and how they want to get there is all-important. Although the public are usu-ally quite visibly involved in the EIS phase of the project — with its many informational presentations and websites describing current details about the developments — their reactions are measured throughout the entire design life. This almost inevitably leads to more opportunities to change or expand the project definition.

chapter 4 | Design Management

6060

Environmental Groups

Public input is required before the approvals can be issued, especially when they in-volve the EPA, the Army Corps of Engineers, and state environmental departments and commissions. This includes written and oral comments presented or submitted during the process. Environmental groups — with either a national or local membership — are usually in attendance at these public meetings. Their positions on the megaproject, whether negative or positive, can have an impact on the project definition, for example, requests to provide amenities such as river walks, recreational facilities, intersection traffic improvements, roadway improvements, or utility improvements. Such requests often occur late in the development phase of the project when budgets and schedules are at their limits and the ability to modify the project definition is limited.

Land Acquisition

The acquisition of property for the project is a major component of the project defini-tion, impacts design solutions, and may constrain possible construction techniques. Be-cause the cost of property, the political nature of property acquisition, and the process to acquire property all have major impacts on megaprojects, at some point during the design process property acquisition must be reduced or ended. If the owners have been unable to obtain a certain parcel of land, the project definition must be revised either by repositioning alignments or facilities, reducing facility sizes, or erecting walls to limit construction.

Owner

From the start of the preliminary design to the start of construction, the definition of the project will be revised many times. One party who contributes to that change is the owner. The owner is typically not an individual but a large organization, with many separate departments, with objectives that initially may not be aligned, but as the proj-ect evolves apparent differences may be negotiated toward a single integrated solution, so that changes to the project may well be necessary. For example, operating depart-ments may develop standards and requirements, some of which may not have been con-sidered in the EIS phase. The project definition often includes expanding the infrastruc-ture to accommodate redundancy or for ease of maintenance. Requests for an increase in the number of substations for electric railroads are frequent project definition revi-sion. Train storage yards often need more utility service points, working power outlets, wider paved aisleways between storage tracks, and weather-protected work areas.

Revisions to the project definition add to the costs, increase the design effort, and

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

6161

extend the design or construction schedule, all of which result in a more costly project due to the increased cost of money.

Regulatory Agencies

Decisions by regulatory agencies during the permitting process often have the effect of revising the project definition. Although the project will already have been defined in the EIS phase, mitigation requirements that arise later during the design process when permit applications are filed will be more specific and will probably expand. For example, mitigation requirements for filling wetlands may increase during the approval process, or expected contributions to wetland banks may become more costly, thus requiring a larger share of the project budget. Whatever the results, the imposed permit conditions become a revision to the project definition.

Collectively, all of these entities contribute to revisions to the project definition, usu-ally at an increase to the project cost and schedule. To maintain the base project is al-most impossible in the present day. During the preliminary design phase, the project definition must be reviewed on a regular basis with current budgets to identify potential project deletions. Components may have to be reduced or eliminated — trading substa-tions for storage tracks or station amenities may be necessary to maintain the budget.

Designer’s Tools

Configuration Management Plan (CMP)

The configuration management plan (CMP) is a process through which the designers are able to define, control, and proactively manage the scope and cost of a project. As stated before, the period spanning the EIS phase and preliminary design is an oppor-tune time for scope growth. Likewise, towards the end of preliminary design and the early stages of final design is another opportunity for scope growth. Sometimes the de-signer proposes ideas to improve project performance, and sometimes the owner wants to improve the project with various modifications during the design phases. If designers and owners do not resist these temptations, the megaproject will increase in scope and cost and additional time will be required to complete the project. To control such scope growth, an explicit procedure to examine the proposed changes and related costs by a group of persons with controlling budget authority and outside the detailed design pro-cess is needed. Although this evaluation procedure would be subject to political forces, at least there would be an opportunity to make a conscious decision about proposed changes and to document the process.

The CMP method has been used to varying degrees on many megaprojects. From the

chapter 4 | Design Management

6262

least-involved process, with just documenting the decision-making process and the de-cisions by the owner and the design team, to formal meetings and detailed analysis by senior management, with presentations by the proposers that fully describe the propos-als, CPM has proved itself capable of controlling megaproject budgets. The authors have also seen examples of successful control of change, for example, when an integrated project control group made up of senior members of the owner’s key departments and designers worked together to comprehend each proposed change and its impact upon the function, cost, and time to complete the project, then agreed to changes only after careful consideration and evaluation.

Work Breakdown Structure

The work breakdown structure (WBS) is the work task that can be assigned a budget and a duration of time that can then be placed into the design CMP schedule. The compi-lation of the WBS elements of the project becomes the project schedule. The more WBS items that can be developed, the better the schedule and budget can be tracked. But the more WBS elements that are developed, the more manpower it takes to track the budget and schedule. A balance will need to be struck between the number of WBS elements and number of staff to track them, depending on the complexity of the project. For mega-projects, the number of WBS elements can be in the thousands. A team of project control personnel is usually required to manage the schedule and budgets. The key is to be able to use “roll-up” WBS tasks so that they can be easily measured, seen, and appreciated by many project team members, thus easing the identification of changing trends.

The upkeep of the WBS elements falls to the discipline managers, as they are respon-sible for the schedule and budget. The managers should also develop the WBS elements for the project because the execution of the work plan, including any interruptions, is critical to meeting the scope requirements.

The details of the scope of work usually have sufficient latitude to allow the discipline managers freedom to develop WBS elements based on their own experience. However, all the managers involved in the project will have input to the WBS. The managers’ contribu-tions to the WBS depend on what is important to them to be tracked in the schedule and budget. Some may want the WBS elements to be of short durations so their progress is reported more often. Others may prefer to have WBS elements set by the scope activities, regardless of duration. Elements designated as “Begin Survey” or “Continue Survey” have no meaning and lack any capability to be tracked. A WBS survey by areas of the project will be more beneficial to tracking schedule and completeness, but usually it is too de-tailed, creating too many elements to track or be subject to revisions, which in turn cause the survey requirements to be adjusted. Striking a balance between the number of WBS elements and the project’s needs is the true test of project management.

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

6363

Status Reports

Monthly or weekly status reports are a way to manage the progress of the design. They have been used to different degrees on different megaprojects. Monthly status re-ports have been used in conjunction with monthly status meetings. Typically, they de-scribe the work started, currently underway, and completed during the month. For each task, the report estimates the percentage completed, which can be compared to its pro-portion in the final budget. The overall cost incurred during the period covered by the report would be presented in another section, which would list the amount spent for the reporting period and calculate it as a percentage of the budget expended.

A status report would also include the date of project submissions and review peri-ods. It helps keep the design schedule in the forefront of the participants’ consciousness and gives everyone current information to discuss at the status meetings.

The report may also contain a log of all the decisions made during the preceding month and the documents where those decisions were recorded (which are usually min-utes of meetings, telephone conversation memorandums, and letters or e-mails). The de-cisions are logged by discipline and numbered and dated for easy sorting in a database.

Recording project details keeps them fresh in people’s memories and tends to keep the design on budget and on schedule.

Design Costs Reports

Besides describing the size or magnitude of these projects, the word mega also de-scribes their costs. With multibillion dollar budgets, a change of even a fraction of a per-centage point represents many millions of dollars. Containing the costs of megaprojects is a full-time job.

Designers must be vigilant in reining in “scope creep,” as there always seem to be bigger and better improvements to the design during its development. Attitudes range from “What’s a few million in the scope of the project cost?” to “Additional spare con-duits are required for future expansion of the system.” Two miles of a 4-inch conduit may not seem like much until all the junction boxes and project multipliers are included, and then it adds up to millions of dollars. The cost escalation becomes far more dramatic if each discipline and each designer add “small” amounts to the project hard costs — but the resulting total would not become apparent until the final roll-up of the project cost.

How then are the project costs controlled in the design phase of the project? A tool that has proved to be useful is a monthly “design cost control report.” Such a report has taken different shapes on different projects, but the result is the same. The report di-vides the design costs into the work breakdown structure (WBS) for each design aspect, contract, discipline, or design unit, so that the costs become small enough to be man-

chapter 4 | Design Management

6464

ageable and recognizable. Too many times the big picture creates a false impression that there is ample capacity in the budget to complete the project. In actuality, there are so many parts to the project that if each discipline requires more budget allocation, it gets to the point that the sum of the allocations exceeds the whole budget. With monthly reporting by WBS, the percentage of the budget spent each month can make apparent how large the total budget will need to be. The monthly reporting of budget consump-tion will require each WBS manager to estimate the percentage complete. (In practice, the estimate of percentage complete should be made before the information on the per-centage spent is made available in order to obtain an unbiased analysis.) The WBS meth-od can effectively describe the design budget condition and flag aspects of the project that require more attention or decision-making.

Buildability Workshops

Buildability workshops at specific phases of the project are very important for mega-projects because the larger a project becomes, the more involved the construction be-comes. Buildability workshops are usually convened with individuals familiar with the construction aspects of the project. For example, on previous projects, buildability workshops included meetings with individual contractors to discuss such topics as: par-ticular construction requirements to determine whether the best possible field condi-tion is being presented, or how can it be made easier for the contractor; issues of piles versus caissons in underwater sites; and the ability to access each site and dispose of the spoils in an efficient manner that minimizes costs. Responses varied depending on the contractor, their equipment, and their experience with the different types of construc-tion. And some owners are not comfortable with the concept of holding a workshop with contractors who may one day bid for the work.

Conducting workshops with members of the construction management industry will probably result in altogether different responses to the same conditions, and the same can be said if the workshop is comprised of designers. Each group brings its own biases to the workshop. The designer has to collate the information obtained in the workshops and determine the direction to proceed in, because there can be more than one right response.

The goal of the buildability workshops is to not pick the wrong response. The design has to be buildable. Each contractor will choose the method that works best for the experi-ence and equipment they bring to the project.

Buildability workshops have proven most beneficial during the preliminary design phase, before the design really progresses, at a point when the results can help develop a foundation for the design decisions before it is too late to redesign. They are also helpful during the final design phase as a way to define the details.

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects

6565

Value Engineering

Value engineering is a useful tool in the design process. Although the design team’s impression of the value engineering team may be that they are only charged with re-ducing the cost of the project, the real goal of value engineering is to achieve the same function of the project at a lower cost. Projects seem to grow in scope the longer the de-sign phase takes, and megaprojects take the longest, so on megaprojects there are more opportunities to grow. Growth is generated by either the owner or the design team. The owner grows the scope of the project when its operating departments think of more items to make the system operate easier, to improve reliability or redundancy, and to provide for future needs. The designer can grow the scope by upgrading finishes and enhancements in public areas to add a degree of elegance to the project.

The value engineering team studies the functions of the project and its components, whether the same function can be accomplished at a lower cost, and what can be elimi-nated or postponed from the project and still achieve the desired result. By the end of the value engineering process, at least some of their proposals will be accepted and in-cluded in the project — causing a redesign.

Design Deliverables

A megaproject will require thousands of documents to define the project and record various facts and data. It is important to specify each of these documents and, where possible, the format, style, and other relevant characteristics. These documents include:

• Drawings• Construction sequences• Specifications• Terms and conditions• Site investigation data reports• Geotechnical data reports• Geotechnical interpretative reports• Geotechnical baseline reports• Calculations• Design reports• Geographical Information System (GIS) to hold these documents and allow the

owner to use them following the completion of the project

It is important that a suitable electronic control and issuing system be used to store and manage the issue data, circulation, and purposes of the project documents. With

chapter 4 | Design Management

66

such a large quantity of documents, some issued a number of times, there will be many thousands of pages. Managing document storage and retrieval contributes to the overall success of the design effort as well as the construction effort. The ability to recall the design information is important to the final transfer of documents from the designer to the contractor. The designer must inform the contractor of the information discovered and produced during the design phase so the contractor is aware of decisions and be-comes as knowledgeable as the designer.

Conclusion

It is beyond question that high-quality, cost-effective design services will contribute to the success and owner’s and users’ satisfaction with a megaproject. Similarly, and per-haps more importantly, the owner’s greatest opportunity to influence the final project costs occurs during the design phase. Accordingly the megaproject owner must insist on rigorous management of the design process and demand accountability by its consul-tants and by its own oversight staff. Avoiding “surprises” during the design phase and demonstrating to the general public a methodical approach to identifying and dealing with the particular project’s challenges and issues will go a long way to bolstering sup-port for the project.

part I | Context, Practices, and Major Issues on Megaprojects