1 1999 Kosturiak J. Comput Ind Simulation in Production System Life Cycle

2014 Ind J Pediatric

-

Upload

nandini-jagan -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

description

Transcript of 2014 Ind J Pediatric

-

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Measuring Brand Awareness as a Component of Eating Habitsin Indian Children: The Development of the IBAI Questionnaire

Maria Gabriella Vecchio & Marco Ghidina & Achal Gulati &Paola Berchialla & Elizabeth Cherian Paramesh & Dario Gregori

Received: 28 March 2014 /Accepted: 1 April 2014# Dr. K C Chaudhuri Foundation 2014

AbstractObjective To develop an instrument that allows one to esti-mate the Indian childrens brand awareness of alimentaryproducts.Methods The IBAI (International Brand Awareness Instru-ment), an age specific tool composed of 12 sheets with imagesreporting brand logos of alimentary products, has been adjust-ed for the Indian context in order to investigate on infantscognitive skills of recalling and recognizing. The IBAI waspiloted in a sample of 100 children aged from 3 to 10 y andenrolled in New Delhi schools.Results Children aged 710 y showed an higher brand aware-ness as compared to those of 36 y.Conclusions The IBAI instrument may be a component forfurther analysis of the influence of food marketing on childsdiet, foods choices and preferences within the Indian socialand cultural macro-context. Findings suggest that childrenover 6 y are particularly gullible by brands and TV promotedadvertising. Prevention through information should, therefore

be offered to school aged children and their parents, involvingteachers, nutritionists and experts in developmental psychol-ogy also.

Keywords Awareness . Brandmarks . Childhood . Foodlogos . IBAI . Eating disorders . India

Introduction

The rate of obese and overweight people is ever-growingworldwide, and childhood and adolescent obesity is nowconsidered one of the most important global plagues [1].While up to some years ago it was especially an issue ofdeveloped countries, now-a-days the problem of weight gainin children is affecting also the developing ones.

India showed an increase of obesity from 4.9 to 6.6 %between 200304 and 200506, and recently the prevalenceof childhood obesity is about 22 % [2]. Although geneticspecific predisposition represents a facilitating factor for thedevelopment of obesity in India [3], several co-causing con-textual factors have to be considered with regard to obesityepidemic.

A switch in traditional diets, due to the popularity of fastfoods, soft drinks and high energy-dense foods, matched tothe rapid spread of sedentary lifestyle patterns, has resulted inthe loss of equilibrium between energy intake and expenditure[4]. Moreover, important determinants of childhood obesity indeveloping countries include high socioeconomic status, mar-keting by transnational food companies and residence in met-ropolitan cities [5]. The latter is a factor widely considered byseveral researchers and specifically in India, it has been dem-onstrated that there is a substantial difference among theprevalence of overweight and obese children in urban areas(11.63 and 2.35 % respectively) compared to children fromthe rural ones (4.7 and 3.63 %, respectively) [6].

M. G. Vecchio :M. Ghidina (*)ZETA Research Ltd., Via Caccia, 8, 34129 Trieste, Italye-mail: [email protected]

A. GulatiDepartment of Otorhinolaryngology (ENT), Maulana Azad MedicalCollege, New Delhi, India

P. BerchiallaDepartment of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University ofTorino, Torino, Italy

E. C. ParameshCollege of Nursing, Lakeside Institute of Child Health,Lakeside Hospital, Bangalore, India

D. GregoriUnit of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Public Health, Departmentof Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, University of Padova,Padova, Italy

Indian J PediatrDOI 10.1007/s12098-014-1447-y

-

The increase of obesity in children living in urbanareas is due to the prevalence of sedentary lifestylesand to the low level of physical activity, compared totheir rural counterparts. Television has come under morescrutiny as a potential cause, enhancing obesity in chil-dren and adolescents [4, 7]. Indeed it can be linked tothe lack of time, which could be used for physicalactivity, promoting, instead, sedentary life attitudes [8,9], often accompanied by consumption of particular en-ergy dense snack foods [10, 11]. Furthermore televisionas mass media, demonstrated a relevant influence onpeoples food choices, due to advertising and commercialcampaigns [12]. Several studies have been conducted toevaluate the relation between TV food advertising andunhealthy food consumption in children, both in short[11, 1315] and in long-term [16]. Most often alimentaryproducts, promoted during childrens and family pro-grams are cereals, snacks, and fast foods [17], many ofwhich are high in complex sugars, saturated fatty acids,and therefore, highly caloric.

Borzekowski et al. [18], then confirmed by Lobstein et al.[19] and recently also by Boyland et al. [20] claimed that foodadvertisements might directly affect intake, by either stimu-lating hunger and/or encouraging children to consume thespecific foods that are promoted. Several other studies sug-gested that food marketing alters childrens preferences forspecific food brands [21, 22], and also the report of theInstitute of Medicine [23] highlighted that marketing cam-paigns, promoting food and beverage, influence the prefer-ences and purchase requests of children. This inference en-hances consumption, at least in the short term, contributing toless healthful diets, as well as negative diet-related healthstatus. Marketing based on brand marks is considered a strat-egy of advertisement in order to enhance recognition of acompany or product, expecting that people, especially chil-dren will develop psychological and cognitive affiliation tosuch aliments, remaining perhaps addicted for the whole spanof life [17]. Up today, throughout the few investigationtools specifically developed in order to analyze elemen-tary school childrens (611 y) attitudes and behaviortowards brand-based aliments, the research instrumentrealized by Forman et al. [24] for US kids, allows toaccess different degrees of brand mark affiliation. Thetool is composed of 30 images showing different logosof food brands. Considering that very popular logos areavailable worldwide, like McDonalds or Coca-Cola but others are country-specific, the original investigationtool had been appropriately developed for the UnitedStates [24].

The main goal of this research was to propose theIBAI as a cultural specific instrument in order to revealchildrens abilities in recognizing and recalling brandswithin the Indian society.

Material and Methods

Stimuli Selection

A selection of 12 representative items of brand logos wasperformed in order to build up the Indian specific IBAI.Consistent to the research realized by Forman et al. [24], theIBAI was created with special attention to the way, the differ-ent brands have been retrieved.

Three clusters of aliments were individuated as dependentvariables: sweet and salted foods as well as carbonated bev-erage. Table 1 shows the whole list of the brand marks takeninto account. These products were chosen according to con-stant confrontations and attend evaluation amongst the re-searchers, working on this project (especially, between psy-chologists and pedagogues). Two criteria in selecting thebrands were used: The aliments had to be available in mostcommon Indian shops and supermarkets and, of course, beingat the same time suitable for kids.

Instrument Development

An age specific tool composed of images, showing differentfood brands was realized in order to access childrens abilitiesof recalling and recognizing specific alimentary products. Thedozen of selected logos were matched with four images, withjust one corresponding to the specific type of snack or bever-age. Twelve sheets for the development of the Indian specificIBAI, defined as so-called flash cards, showing one logo andfour different alternatives of food typeseach of themmatched to the logo and places on the top of the cardwererealized (Table 1). Some examples of the cards are illustratedin Fig. 1.

All images, showing overall 12 brand logos and 48 differ-ent alimentary products (four for each logo), were designed on811.5 sheets and collocated within a binder for the experi-mental phases [24].

Study Sample

Overall 100 children, gender balanced and aged 3 to 10 y,were gathered from school contexts in New Delhi. These kidsconstituted the sample for the creation of the Indian specificIBAI. With regard to ethical standards, it was ensured thatchildren do not present mental and cognitive diseases. In-formed consent was administered to all parents of the infantsrecruited for the study.

Study Conduction

The IBAI was administered to the 100 selected children foranalyzing their recognition and recall ability. Especially therecalling task regards the naming of the brand, as indicated by

Indian J Pediatr

-

Forman et al. [24]. Also food items were included, whosebrand etiquettes are different from some of the promotedproducts names (i.e., brand: McDonalds; product: Big

Mac; food: hamburger). Through accessing the product nam-ing task, it was assumed, that this tool might promote areliable parameter in order to understand how children be-come aware to specific brands and aliments.

Children were exposed to each flash card of the IBAIseparately. For every single sheet infants were invited toanswer to three questions, in order to verify her/his knowledgeabout the brands and about the products associated with theselected items. Pointing at the image of the logo, the experi-menter asked Do you know the name of this logo? Oncechildren answered, tracing a circle with the forefinger over thefour illustrated products, the experimenter said choose thefood that matches with the logo. Finally, when the childselected a food picture, the experimenter asked Which isthe name of this product? The experimenter did not informthe children if the responses were right or not.

For all cards the researcher assigned 1 point to the correctnaming of the logo, 1 point if the kid correctly matched thename to the logo and finally 1 point if the kid remembered thename product. Scores of the brand awareness, according to theadministered cards, shift from 0 to 36 point (3 points for the 12sheets). Throughout this range, it was possible to distinguishfour separated clusters with regard to different degrees ofbrand awareness: 012 very low brand awareness; 1318medium-low brand awareness; 1924 medium-high brandawareness; 2536 very high brand awareness.

Statistical Analysis

A linear regression model was fitted to estimate the effect ofage and gender on total IBAI score. In order to analyze thedifferences according to the three tasks of the IBAI (the brandnaming, the brandproduct association, and the productnaming), ANOVA for repeated measures was applied.

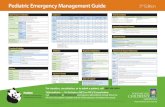

Table 1 International Brand Awareness Instrument (IBAI) - India

Flash carda Brand Solution Product A Product B Product C Product D

1 Coca Cola A Coca Cola Milk Orange Chocolate

2 Mc Donald C Pasta Toast Hamburger Fish

3 Mother Dairy A Milk Orange juice Tea Strawberry syrup

4 Hippo A Munchies Normal potatoes Chips Stick chips

5 Britannia B Chocolate Plum cake Croissant Gummy candies

6 Kinder A Egg shape chocolate Chocolate bar Caramel chocolate Tablet chocolate

7 Kellogs C Peanuts Cornflakes Chocolate cereals Potatoes

8 Maggi B Fish Nuddles Roast beef Sandwich

9 Cadbury D Lollipop Chips Wafer Chocolate

10 Lays C Ice Cream Wafer Potato chips Chocolate

11 Amul Butter A Butter Donut Candies banana Soup

12 Thums Up C Lemonade Orange juice Cola Milk

a List of brands and products presented in the flash cards of the IBAI with the solutions of the correct brand and the product associations

Fig. 1 An example of flash card used in the IBAI. The logo of Coca-Colawas associated with milk, orange-juice and chocolate, producing a singlecard with five images (correct match = image a)

Indian J Pediatr

-

Distributions of correct match within each IBAI task areshown through boxplots.

Results

The distribution of childrens answers according the correctrecognition of the brands name, the correct association be-tween the logo and respective product, as well as the correctnaming of the food type, that emerged from the IBAI areshown in Table 2. With regard to the overall performance ofevery single kid, the major part (70 %) claimed a very lowbrand awareness, 20 % of them a low one, 9 % a mediumlevel, while just 1 % exhibited a high awareness (Table 3).

According to age, results demonstrated that the group ofchildren aged 36 presented a significantly lower brandawareness (about seven points lower, p

-

children learn perceptual categories just during the first mo-ments after birth [39], associative recognition abilities, pro-duced through sub-serving selective attention circuits, comeonline substantially later [38].

Findings of neuro-scientific and psycho-cognitive re-searches contribute in understanding how humans and espe-cially children learn to associate perceived reality to symbolicmeanings of social relevance. Skills in recognizing andrecalling products names, then associated to specific brandlogos, exposed to children during the experimental setting ofthe present study, revealed higher levels in the older agegroup, confirming that such abilities are due to advancementof linguistic and cognitive development.

Attention should therefore be paid by professionals in thehealth sector, parents and teachers, in order to prevent children

against manipulator food-linked advertising. Critical abilitiesin assisting commercial campaigns, especially promoted bytelevision broadcasts, should therefore be empowered just inearly age. Also the choice of available channels must bemonitored by childrens caregivers for granting infants suit-ability to age appropriate broadcasting.

Though the experimental setting revealed interesting find-ings about infants associative skills in recognizing andrecalling advertise-promoted food brands, above all in relationwith cognitive and intellectual development, the sample, con-stituting this pilot project, involved just 100 children. Despitethe limited size of researchs population, socio-demographicvariables were quite homogeneous, considering only childrenbelonging to alphabetized backgrounds in New Delhi. Giventhe poli-geographical and pluri-cultural structure of worlds

Table 3 Childrens total IBAIscore Females Males Total

36 y 710 y 36 y 710 y N %

N % N % N % N %

012 24 96 8 32 27 93 11 52 70 70

1318 1 4 11 44 2 7 6 29 20 20

1924 0 0 5 20 0 0 4 19 9 9

2536 0 0 1 4 0 0 0 0 1 1

Total 25 100 25 100 29 100 21 100 100 100

% Correct brand name % Correct brand & product name % Correct product name

020

4060

80

Fig. 2 Percentage of correctresponses for the three tasks ofIBAI

Indian J Pediatr

-

seventh largest nation, forthcoming studies should be extend-ed to other Indian regions, allowing comparison amongstvarious contextual and socially diversified samples.

Conclusions

This study contributes to existing knowledge in measuringhow Indian children are aware of specific food-related brandmarks, commonly promoted by television advertising. Theexperimental setting designed for the research allowed toaccess childrens skills in associating alimentary products,usually available in local supermarkets, to the respective brandlogo. Findings showed that age resulted to be the primaryfactor in performing cognitive exercises, due to attentionrelated abilities in selecting specific patterns from perceivedreality. Such mental functions are involved in developingpsychological and emotional affiliation to eating habits, pro-moted by visual marketing strategies.

Contributions MGV, AG and DG: Designed the study; MGV, PB andECP: Wrote the manuscript; MG and PB: Performed the statistical analy-sis. All authors contributed to results interpretation, read and approved thefinal manuscript. DG will act as guarantor for this paper.

Conflict of Interest None.

Source of Funding This work is partially supported by an unrestrictedgrant from the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Directorate General forCountry Promotion, and from Prochild ONLUS (Italy).

References

1. Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM,Williams J, Olsson CA,et al. Overweight and obesity between adolescence and young adult-hood: a 10-year prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:27580.

2. Gupta N, Shah P, Nayyar S, Misra A. Childhood obesity and themetabolic syndrome in developing countries. Indian J Pediatr.2013;80:S2837.

3. Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C. Rising burden of obesity in Asia. JObes. 2010; doi:10.1155/2010/868573.

4. Kuriyan R, Bhat S, Thomas T, Vaz M, Kurpad AV. Televisionviewing and sleep are associated with overweight among urban andsemi-urban South Indian children. Nutr J. 2007;6:25.

5. Gupta N, Goel K, Shah P, Misra A. Childhood obesity in developingcountries: epidemiology, determinants, and prevention. Endocr Rev.2012;33:4870.

6. Ghosh A. Ruralurban comparison in prevalence of overweight andobesity among children and adolescents of Asian Indian origin. AsiaPac J Public Health. 2011;23:92835.

7. Hancox RJ, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Association between child andadolescent television viewing and adult health: a longitudinal birthcohort study. Lancet. 2004;364:25762.

8. Ranasinghe CD, Ranasinghe P, Jayawardena R, Misra A. Physicalactivity patterns among South-Asian adults: a systematic review. Int JBehav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:116.

9. Eisenmann JC, Bartee RT, WangMQ. Physical activity, TV viewing,and weight in U.S. youth: 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. ObesRes. 2002;10:37985.

10. Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships be-tween use of television during meals and childrens food consump-tion patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E7.

11. Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect oftelevision advertisements for foods on food consumption in children.Appetite. 2004;42:2215.

12. Robinson TN. Television viewing and childhood obesity. PediatrClin North Am. 2001;48:101725.

13. Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL, Paluch RA, WiniewiczDD, Fuerch JH, et al. A randomized trial of the effects of reducingtelevision viewing and computer use on body mass index in youngchildren. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:23945.

14. Halford JC, Boyland EJ, Hughes G, Oliveira LP, Dovey TM.Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of 57-year-oldchildren. Appetite. 2007;49:2637.

15. Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in themarketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesityand what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:21125.

16. Barr-Anderson DJ, Larson NI, Nelson MC, Neumark-Sztainer D,Story M. Does television viewing predict dietary intake five yearslater in high school students and young adults? Int J Behav Nutr PhysAct. 2009;6:7.

17. Connor SM. Food-related advertising on preschool television: build-ing brand recognition in young viewers. Pediatrics. 2006;118:147885.

18. Borzekowski DL, Robinson TN. The 30-second effect: an experi-ment revealing the impact of television commercials on food prefer-ences of preschoolers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:426.

19. Lobstein T, Dibb S. Evidence of a possible link between obesogenicfood advertising and child overweight. Obes Rev. 2005;6:2038.

20. Boyland EJ, Halford JC. Television advertising and branding. Effectson eating behaviour and food preferences in children. Appetite.2013;62:23641.

21. Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Lane TS, Sanders AK. Television foodcommercials aimed at children, family grocery shopping, andmother-child interactions. Fam Relat. 1981;30:4359.

22. Robinson TN, Borzekowski DL, Matheson DM, Kraemer HC.Effects of fast food branding on young childrens taste preferences.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:7927.

23. McGinnis JM, Gootman JA, Kraak VI. Food marketing to childrenand youth: threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: NationalAcademies Press; 2006.

24. Forman J, Halford JC, Summe H, MacDougall M, Keller KL. Foodbranding influences ad libitum intake differently in children depend-ing on weight status. Results of a pilot study. Appetite. 2009;53:7683.

25. Wang Y, Chen HJ, Shaikh S, Mathur P. Is obesity becoming a publichealth problem in India? Examine the shift from under- to overnutrition problems over time. Obes Rev. 2009;10:45674.

26. Gupta R, Gupta KD. Coronary heart disease in low socioeconomicstatus subjects in India: an evolving epidemic. Indian Heart J.2009;61:35867.

27. Chandra PS, Abbas S, Palmer R. Are eating disorders a significantclinical issue in urban India? A survey among psychiatrists inBangalore. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:4436.

28. Popkin BM, Horton S, Kim S, Mahal A, Shuigao J. Trends in diet,nutritional status, and diet-related noncommunicable diseases inChina and India: the economic costs of the nutrition transition. NutrRev. 2001;59:37990.

29. Wasir JS,Misra A. TheMetabolic syndrome inAsian Indians: impactof nutritional and socio-economic transition in India. Metab SyndrRelat Disord. 2004;2:1423.

Indian J Pediatr

-

30. Joseph B, Rebello A, Kullu P, Raj VD. Prevalence of malnutrition inrural Karnataka, South India: a comparison of anthropometric indi-cators. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20:23944.

31. RaniMA, Sathiyasekaran BW. Behavioural determinants for obesity:a cross-sectional study among urban adolescents in India. J PrevMedPublic Health. 2013;46:192200.

32. Misra A, Singhal N, Sivakumar B, Bhagat N, Jaiswal A, Khurana L.Nutrition transition in India: secular trends in dietary intake and theirrelationship to diet-related non-communicable diseases. J Diabetes.2011;3:27892.

33. Story M, French S. Food advertising and marketing directed atchildren and adolescents in the US. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act.2004;1:3.

34. Caroli M, Argentieri L, Cardone M, Masi A. Role of television inchildhood obesity prevention. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord.2004;28:S1048.

35. Best CA, Yim H, Sloutsky VM. The cost of selective attention incategory learning: developmental differences between adults andinfants. J Exp Child Psychol. 2013;116:10519.

36. Vygotskij LS. Mind and society: the development of higherpsychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press;1980.

37. Maguire MJ, Abel AD. What changes in neural oscillationscan reveal about developmental cognitive neuroscience: lan-guage development as a case in point. Dev Cogn Neurosci.2013;6:12536.

38. Sloutsky VM. From perceptual categories to concepts: what de-velops? Cogn Sci. 2010;34:124486.

39. Quinn PC, Eimas PD, Rosenkrantz SL. Evidence for repre-sentations of perceptually similar natural categories by 3-month-old and 4-month-old infants. Perception. 1993;22:46375.

Indian J Pediatr

Measuring Brand Awareness as a Component of Eating Habits in Indian Children: The Development of the IBAI Questionnaire AbstractAbstractAbstractAbstractAbstractIntroductionMaterial and MethodsStimuli SelectionInstrument DevelopmentStudy SampleStudy ConductionStatistical Analysis

ResultsDiscussionConclusionsReferences