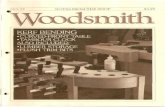

#077, In Practice, May/June 2001

-

Upload

hmi-holistic-management-international -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

6

description

Transcript of #077, In Practice, May/June 2001

Igrew up on a cattle ranch in rural

northwestern Montana that my great-

grandparents settled in the 1880s. As a child,

I was surrounded by my extended family, as

well as neighbors who worked with us on a

regular basis. I was involved in the daily chores

and my responsibilities grew as I did.

My grandparents were strong advocates

of education and world travel, as were my

parents. So, while the setting was rural, I was

routinely exposed to a variety of art, music,

museums, and people. I can now appreciate

how difficult it was for my family to provide

this, given the demands of ranch work and

the rural locality. But, being a typical young

person, my thoughts were, “there must be

more to life than this.”

Due to the exposure to family friends of

many cultures and experiences, I flew to Japan

after graduating from college. I landed in

Kumamoto, Japan with 50,000 Yen ($500) in

my pocket and three Japanese words in my

vocabulary. I stayed there for three years and

learned more about myself and what I valued

than I ever could have imagined. But an even

greater lesson awaited me at home.

A New Lease on Life

Over the years, my parents alternately

swung between wanting to encourage their

children to return home and convincing us that

agriculture was a life of hardship and struggle.

They were convinced that they did not want to

impose this kind of struggle on their children,

but also wanted one of us to continue the

ranching legacy that was important to all of us.

In the midst of the Rocky Mountains, we

were one of the few families that were not

dependent on the local timber mills and

logging industry. With that came a certain

independence, which allowed us to view things

from a different perspective than our neighbors.

But like our neighbors, my family also

experienced the consequences of U.S. Forest

Service (USFS) policy regarding grazing on the

public land. New policies and public sentiment

made it more difficult and costly to continue

operating. My parents felt cornered by their

need for the leased grazing land, which had

been a part of the ranching “system” since my

great-grandparents began. It appeared that there

were two choices: accept the new system and

make do, or cut down the number of animals

and graze a smaller number at home year-

round. Neither option was appealing, and both

would have negative financial ramifications, not

to mention the depreciating quality of life. It

was approximately at this time that my parents

sought and found a third option—Holistic

Management.

At this point, I had been living in Japan for

three years, and had very little to do with the

ranch. I wasn’t aware of the new information

and way of thinking that they had discovered.

Upon my return, in 1997, I found that the

ranch had undergone a transformation.

The physical changes included an entirely

new grazing plan that required a multitude of

new fences. Several dilapidated buildings had

been taken down or replaced, while some

little-used machinery had been sold. They sold

our uncle’s uninhabited trailer, some horses,

and some equipment, and put in a new pond

in the upper pasture.

Most noticeable were the changes in my

parents. For 25 years they had battled the land,

the community, and the local USFS agents,

trying to “make a living” and “follow their

dream” as ranchers. For many of these years,

they had been financially over-burdened,

emotionally drained, and physically exhausted.

They were close to selling the ranch, but were

in t h is I s su e

Holistic Management—Ten Years

and Counting

Brenda (Younkin) Kury . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Ruminations from the Second

Generation

Tyler Dawley . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

An Optimistic Revolution in a

Pessimistic World

Tyler Dawley . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

LAND & LIVESTOCK—A specialsection of IN PRACTICE

The New Ranching Economy—

Diversity and Creativity on the

Chico Basin Ranch

Duke Phillips . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Common Values, Common Language

Jim Howell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Monitoring with Open Eyes

Tony Malmberg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

Savory Center Bulletin Board . . . . . . .14

Development Corner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Center Supporters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Marketplace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Amy Driggs, in her article “Holistic

Management—The Next Generation,”

offers a glimpse into the world of a

young person introduced to Holistic

Management. Like the other contributors

in this issue, she articulates the

importance of having a purpose in lif e

and meaningful work and explains ho w

Holistic Management is a means to that

end. Moreover, it’s a tool that has helped

these young adults achieve success.

Holistic Management—

The Next Generationby Amy Driggs

MAY / JUNE 2001 NUMBER 77

HOLISTICMANAGEMENT IN PRACTIC EP r oviding the link between a healthy environment and a sound economy

continued on page 2

2 HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE #77

The Allan Savory

Center for Holistic Management

The ALLAN SAVORY CENTER FOR

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT is a 501(c) (3)

non-profit organization. The center

works to restore the vitality of

communities and the natural resources

on which they depend by advancing the

practice of Holistic Management and

coordinating its development worldwide.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Lois Trevino, Chair

Rio de la Vista, Vice Chair

Ann Adams, Secretary

Manuel Casas, Treasurer

Gary Rodgers

Allan Savory

ADVISORY BOARD

Robert Anderson, Chair, Corrales, NM

Ron Brandes, New York, NY

Sam Brown, Austin, TX

Leslie Christian, Portland, OR

Gretel Ehrlich, Santa Barbara, CA

Clint Josey, Dallas, TX

Doug McDaniel, Lostine, OR

Guillermo Osuna, Coahuila, Mexico

Bunker Sands, Dallas, TX

Jim Shelton, Vinita, OK

Richard Smith, Houston, TX

STAFF

Shannon Horst, Executive Director; Kate Bradshaw, Associate Director; Allan Savory, Founding Director; Jody Butterfield, Co-Founder andResearch and Educational MaterialsCoordinator ; Kelly Pasztor, Director of Educational Services; Andy Braman,

Development Director; Ann Adams,

Managing Editor, IN PRACTICE andMembership Support Coordinator

Africa Centre for Holistic Management

Private Bag 5950, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe

tel: (263) (11) 213529; email:

Huggins Matanga, Director; Roger and

Sharon Parry, Managers, RegionalTraining Centre; Elias Ncube, HwangeProject Manager/Training Coordinator

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT INPRACTICE (ISSN: 1098-8157) is publishedsix times a year by The Allan SavoryCenter for Holistic Management, 1010Tijeras NW, Albuquerque, NM 87102,505/842-5252, fax: 505/843-7900; email:[email protected].;website: www.holisticmanagement.org Copyright © 2001.

Ad definitumfinem

The Next Generation continued from page one

so tied to the family legacy that they couldn’t

bring themselves to do it. While the tradition

and romance associated with the yearly cattle

drives to the summer range is gone, they have

traded nostalgia and old traditions for a stable,

rewarding business, improving their quality of

life 100 percent.

Upon my return from Japan and the

following few years, my parents began

involving me in some of their decision-making.

They introduced me to Holistic Management

subtly, explaining the changes they were

making without attributing them to Holistic

Management. Finally, after some gentle

prodding by my father, I watched Allan

Savory’s videotaped lecture. That was all it

took. Two hours later, my entire perspective

had changed.

No Turning Back

This new way of viewing the world has

pervaded every corner of my life: career,

relationships, hobbies, gardening, driving,

shopping, traveling, speaking, thinking, eating,

and breathing. There’s nothing I do now

without first thinking of how I am affecting

the world around me, of how far reaching my

decisions can and should be, of how I want to

live my life everyday, and how much I hope

for others to have the same life-changing, life-

enriching, all-pervasive experience.

Raised in a Catholic family, my personal

spirituality is an integral part of my character.

But faith and vision must be married to

action and commitment. Holistic Management

requires the absolute involvement and

commitment of humans. It demands a

commitment to decision-making, and when

a decision or plan fails, there is a means for

determining how and where the failure

occurred. Rather than telling people what to

accept, what to believe, what to do, it requires

individuals to accept their own power of

thinking as intelligent creatures, to have faith

in their own abilities. To me it embodies the

Judeo-Christian value that I hold dearest,

“God helps those who help themselves.”

And for young people, Holistic

Management gives us the tools to answer the

question, “Isn’t there more to life than this?”

For me this meant, “Isn’t there more to life

than living in Silicon Valley?” which is where

I resided after returning to the U.S. from

Japan. There I felt like I was competing with

everyone else to attain that dream house and

car in the suburbs so that I could commute

two hours to work every day.

Lucky for me, my parents knew there

was more to life, and lucky for me, Holistic

Management became a part of my life early on.

And all of those old cliches, like “You’re only

limited by your imagination,” have taken on a

sincere meaning in the way I make decisions

and lead my life. The last year learning and

practicing Holistic Management has taught me

more about how to get the life I want than

any university class or intercultural experience

has in the last 15 years.

Last spring I promised myself that I would

start making changes that would lead me closer

to the life I want. In May I quit my stressful job

in California. In June I started the Holistic

Management™ Certified Educator’s Training

Program. I spent the following three months

on the ranch in Montana working with my

parents. This gave me an opportunity to see

the grazing plans in action, not to mention the

bonus of spending time with my family in

the glory of a Montana summer.

In October I moved to Albuquerque where

my other half, Jeff, is getting his Ph.D., and by

November I had two new jobs working with

people I respect and admire. I work half time

at Tree New Mexico with Sue Probart, a fellow

student in the Training Program. I also work

half time at Orbus International with Ken

Jacobson, a Certified Educator. Working so

closely with them allows me to see Holistic

Management at work in a variety of settings.

And, of course, there are the gradual changes

that are taking place in my home and in my

relationship with Jeff and the rest of my family.

Most recently, Jeff and I have instituted a financial

plan to make the transition from our big-wage

jobs in California, to the much more frugal

lifestyles of students. We both have plans for

the future that include more travel and adventure,

but we also keep an eye to the future of the

ranch. In the past this seemed like an

insurmountable undertaking, based on my

parent’s trials and our own inexperience. But

with the continued changes, our own growing

interest, and the tools apparent through Holistic

Management, a life on the ranch is now something

we enjoy dreaming about and planning for

instead of fearing as a looming responsibility.

Amy Driggs can be reached at:

1131 Los Tomases NW, Albuquerque, NM 87102;

505/242-2787; [email protected]

Most of my childhood was spent

in the Sand Hills of Nebraska.

My dad is a cowboy, and we have

always found common ground in livestock

and pastures. In high school, Dad and I

would test our plant identification skills and

try to stump each other on our way back

to the barn. We would talk about grazing

systems and look at changes taking place in

different pastures that had been grazed at

different times. Those childhood days of

riding through pastures sparked my interest

in range management, which continues to

this day.

I was first introduced to Holistic

Management (then Holistic Resource

Management) in 1990. The ranch my parents

were working for had been sold. The new

owners managed holistically, so the first order

of business was to send all employees (and

interested spouses) to an introductory Holistic

Management course. My dad went to his first

Holistic Management course and brought

home several very interesting ideas with

which he began to experiment.

As an active member of Future Farmers

of America (FFA), I was always looking

for speech topics. In 1991, I chose Holistic

Management as my presentation focus for a

regional public speaking contest and learned

more about Holistic Management in the

process. I had no idea how much Holistic

Management would become a part of

my everyday life.

As my parents learned more about

Holistic Management, I began to see some

changes in them. They were both involved in

the ranch. We (as a family) started discussing

goals, and dad would use the dinner table as

a place to bounce ideas off of all of us. My

mother was also raised on a ranch, and was

able to provide valuable suggestions, as did

my sister who also helped out on the ranch.

As part of this exploration I found out that

I could actually make a career in range

management and structured my college

courses accordingly.

By the time I was in college, I decided I

needed to attend Claude and Annette Smith’s

introductory Holistic Management course so I

could really understand the principles. Between

learning about the Smith’s successes with

desired end point.

One of the key points in our quality of

life statement is that we want our work and

home life to be harmonious. Many people see

these two entities as separate and, therefore,

they assume that their work life will not

affect their home life. They think they can

compromise the one without compromising

the other. But through Holistic Management,

I have learned that such separation can cause

conflict if the whole family isn’t involved in

the decision-making process around careers.

That’s why my husband and I took time

together to decide which job for me best fit

our holistic goal and compared the available

positions to that goal.

Use A l l Your Resources

My resources include my family, my

ability to reason, my Rolodex, research, and

many other items. Monitoring allows me to

identify the weak link or a logjam, and re-

planning allows me to use different resources

as necessary. As with any job, applying the

proper tool makes the job much easier, and

I can evaluate the tools at hand and add

others as necessary.

More than once the task at hand became

easier when I realized I needed a different

tool to do the job right. Holistic Management

has taught me to think around corners and

know that “but we’ve always done it that

Holistic Management and my family’s

experience, I decided that I would keep the

key principles in mind to help me be more

successful in life. I’d like to share some of

these principles with you.

Plan, Monitor, Control, Re-plan

These four words form the basis

of my day-to-day existence. They

help me stay organized and flexible,

even when everything doesn’t go as

originally planned. They have taught

me to think about my actions and

the effect those actions have on

the whole.

Before we were married, my

husband and I lived in different states.

He was in eastern Colorado, and I

was in eastern Nebraska. After he

proposed, we had some heavy-duty

decisions to make. Who was going to

move? What would happen with our

jobs? Where would we live? These

items (and many more) needed to be

added to our plan, and we only had about

six months.

After a momentary descent into chaos,

my training in Holistic Management finally

kicked in. We evaluated both of our jobs

and decided that I would keep my position

in Nebraska and he would relocate because

he could telecommute. But when funding

for my position suddenly became

unstable, we had to pull out our plan

and revise it.

We decided the best thing for us to do

at that point was for me to resign, move

to Colorado, and look for a position there.

Within six weeks, I found my current

position, finished making wedding plans,

and moved to Colorado. Many changes took

place within a very short period, but we

were able to move through it with relative

ease by sticking with the principles of

Holistic Management.

E yes On the Prize

I always have a series of goals or

objectives. This helps me keep the big

picture in sight, and allows me to know if

my daily adjustments/decisions are moving

me closer to or further away from the

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 3

Vernon and Brenda Younkin

Holistic Management—

Ten Years and Counting by Brenda (Younkin) Kury

continued on page 4

way” is not a valid reason.

For example, I had a very fulfilling

position as the Grazing Lands Specialist that

was the product of a cooperative agreement

between Nebraska Cattlemen and the Natural

Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). The

agreement itself was a new solution to an

old problem—NRCS had too few people to

address the public need for assistance with

grazing and pasture issues. Nebraska

Cattlemen had members whose needs for

technical assistance weren’t being met. The

solution was to develop the Grazing Lands

Specialist position.

Many of the problems I dealt with on a

daily basis had solutions that seemed clear

to me (a new set of eyes), but weren’t

immediately obvious to the producer. For

example, a producer I worked with was

very concerned about heavy trailing (trails

left by livestock) in his pastures. He was

concerned about the condition of his

pastures, but his budget didn’t have room

for costly improvements (e.g., additional

water sites). Our solution?

The producer began using a combination

of salt and mineral tubs that he moved

around the pasture. We developed a five-year

plan to first spread old hay in the heavily

eroded areas, then encouraged his livestock

(again, through salt and mineral tubs) to

trample the area for a brief time. Areas

nearest the watering site were trampled on

a controlled basis and access was restricted

the rest of the time. Additional watering

sites were planned over the next three

years. The result?

Trampled areas quickly began to

revegetate and weed populations decreased.

In an area receiving 620 mm (25 inches)

or more of precipitation annually, grass

production was not the problem—we just

applied different tools (animal impact) to

his problem.

Applying the Principles To d a y

Since 1991 I have completed a bachelor’s

degree in Range Science and completed

fieldwork for a master’s degree in the same

discipline. As a student, consultant, and now

as an environmental planner, the principles of

Holistic Management have traveled with me.

I now use them in my work for the Center

to begin addressing ecosystem-level processes

and use my knowledge of the tools, testing

guidelines, management guidelines, and

Holistic Management™ land planning to

help develop a new plan.

The first step was to assess what was

already in place and see how we could best

use and include those people, agencies, plans,

and processes already involved: the Fire

Management Plan, the Pest Management

Coordinator (for noxious weeds), and the

Environmental Office (responsible for weed

control near native, threatened, or endangered

plant populations).

As planners we then proposed

management recommendations that would

incorporate the appropriate sections of

existing plans and offices, as well as suggested

new ideas like initiating a weed education

program for recreationists, more aggressive

feral ungulate control, and continued manual

and chemical weed control. While current

monitoring centered around roadways and

threatened and endangered plant populations,

we recommended expanding the weed

monitoring program to include recreation

access points, all areas with feral ungulate

populations, and areas where weed control

is currently taking place. A better reporting

method was also established to improve the

evaluation of control measures. In other

words, we tried to expand people’s

perception of the whole habitat rather than

just around certain plants (i.e., endangered).

To accomplish all of the specific goals

and objectives outlined in the INRMP, the

environmental staff would have to triple in

size. We, as planners, know this is not likely

to happen given current budget restrictions

placed on federal agencies. However, we

chose to develop the plan as an overview

of where the weed control program could

be improved, and suggested incremental,

measurable objectives to guide the way to

achieve more holistic results.

Holistic Management has provided me

with a framework to use to focus my life.

It unites my home and my work, and has

given me a competitive advantage over

many of my peers. Holistic Management

has improved the quality of life for me and

my family, and reminds me daily to check

my actions against my goals and to ask

myself, “Am I going the right direction?”

Brenda lives in Greeley, Colorado

with her husband, Vernon, and can be

reached at: [email protected]

for Ecological Management of Military Lands.

Holistic Management promotes the use of

common sense. Its principles require that you

get to the root of the problem and determine

a solution based on the cause of the problem,

not on the undesired effect it is causing. But

sometimes circumstances are such that you

often cannot really address the root cause.

Nonetheless, you can still improve the

situation by getting more constituents to

look at the bigger picture. This strategy is

something I used when I developed a weed

management plan as part of the Integrated

Natural Resource Management Plans (INRMP)

for military lands in Wyoming and Hawaii.

Military lands, as part of the public land

system, are regulated by a myriad of laws

rules that regulate sustainable, multiple-use

activities (i.e., hunting, fishing, non-

consumptive uses) and allow public access

when safe (i.e., access is not allowed when

training is taking place). Ensuring the INRMP

meets the requirements of all state and

federal regulations is no small task, even with

the specific task of “weed management.”

Historically weed management for military

lands in Hawaii consisted of removing

weeds (including alien plants), chemically or

manually, near endangered plant populations.

This approach did not have the desired

impact of reducing weeds throughout the

property. Instead, it created fragmented

havens for native plants without addressing

the root of the problem, which was a

changed habitat or ecosystem that favored

the alien plants.

Using the Holistic Management™ model,

I was better able to see all the influences

that continued to nurture that changed

habitat: frequent fire, continued introduction

of alien species, and human impacts. I was

then able to restructure the agency objectives

4 HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE #77

Ten Years and Counting continued from page 3

Holistic Management

has given me a

competitive advantage

over many of my peers.

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 5

atmosphere, where communication, trust

and acceptance were all present.

This goal wasn’t surprising considering

how each of these siblings grew up with the

ranch. Now that they were adults, finding

another place like it would not be easy. If

they lost the ranch, they would lose their

connection to their past, and to a future

on the ranch for their children. They had

to find a way to help support the ranch

while maintaining their commitments to

jobs and children and living three and a

half hours away.

The extended family wasn’t sure about

what forms of production they wanted to

support the ranch. What they wanted from

the ranch wasn’t money; they wanted this

family ranch, its history and its future. And

while they would not physically help with

production, they were aware they

needed to help the ranch with

more than just good intentions.

A Family Decision

As we mulled over the issue of

production and revenue, we used

the Holistic Management™ decision

making process to determine which

enterprise we would focus on in

the coming year. We looked at

expanding our cattle operation,

grapes, walnuts, and recreation.

The cattle couldn’t generate the

income we needed quickly enough;

and the grapes and walnuts

required years and labor that the

ranch could not afford. Obviously,

at that time, recreation was the

future of the ranch.

With the other means of

production out of our focus, the current

inadequacies of recreation became clear. We

needed more clients. This logjam could be

solved through increasing customers, which

was something the whole family could do.

After our most productive brainstorming

session yet, we narrowed down our ideas to

one tremendous one—a lakeside cabin.

We built the cabaña, as the cabin was

soon called, in April of 1994. The building

Ruminations From the Second Generationby Tyler Dawley

continued on page 6

hen Ann Adams approached me

to write this article, I was excited

by the prospect of sharing my

personal and family views on life. Holistic

Management encompasses my entire view

of the world. Indeed, as a second generation

holistic manager, I have had no other option

than to look at the world from a larger

perspective—the Holistic Management

perspective. Draft after draft, I failed to

write a piece that truly encompassed

my views.

After many conversations with my family

about what I should write, I realized that

my entire approach was incorrect. I was

trying to write about my views on Holistic

Management, but I could not tell it solely

from my perspective. Holistic Management

deals with the whole picture, which

for me includes my family and the

family ranch—in its entirety.

Finding a Way

My family’s connection to Big

Bluff Ranch started in 1960 when

my mother’s parents purchased it.

The ranch became a family retreat

from the complicated, if not

dangerous, life of Berkeley in the

‘60s. My mother, Vicky, the youngest

of her siblings, grew up knowing

about cows and horses and all that

her city friends never understood.

In the fall of 1976, my parents, Frank

(hailing from Santa Barbara and

knowing more about sailboats than

cows) and Vicky, chose to move to

the ranch. They thought they would

spend a year or so on the ranch

then go back to “real” life. Now, over

25 years and three kids later, they merely

shake their heads and say it never occurred

to them to leave. I was born in the city

nearest to the ranch (only 30 miles away)

and was raised on the ranch with my two

younger sisters.

In my early childhood, my parents first

began learning about Holistic Management. It

energized them. They began whole-heartedly

changing their ways. It wasn’t until the late

‘80s that the rest of the extended family

began to catch on. This was important

because my grandparents had already passed

down ownership of the ranch to my mother

and her three siblings. Through Holistic

Management, they realized that if they were

to all own the ranch, they must all take an

active, even if remote, role in the ranch.

They went to their first Holistic Management

workshop in 1991. This renewed their bonds

with one another and they rediscovered

their shared love for this ranch.

While that workshop had a profound

effect on the family, change didn’t come over

night with many busy lives. But in August

of 1993 the family congregated to discuss the

ranch and its situation. By this time, I was

15 and had spent my life “looking at the

whole picture.” I joined in as we strove to

define the “whole under management.”

Who’s In Charge?

All of the siblings, except my mother,

lived off the ranch; they didn’t have a day-to-

day operational interest in the ranch. How

could they be in charge? Who was in charge?

Did it matter? And though we were working

from a temporary holistic goal, this meeting

provided a forum to discuss ideas from

which some clear trends started to emerge.

The family wanted a self-supporting place

that embodied work and fun in a “homelike”

Tyler Dawley with his goats on the Red Bluff Ranch. The goats

are a new enterprise on the ranch in an ef fort to diversify

operations for increased profit and health of the land.

W

6 HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE #77

Holistic Management has helped me to understand what needs to

be done for the world. I am optimistic rather than pessimistic,

which is surprising considering all of the problems in the world.

Through my understanding of and experience with Holistic

Management, I am better able to see that all people want basically

the same thing: security and longevity. They want the world to

support them comfortably, and for it to be in good condition for

their children.

All of the holistic goals that I have ever seen express these similar

desires, and Holistic Management helps people to achieve these

desires. When people work toward their personal holistic goal, which

has desires in it that all people want, then as they achieve their

personal goal, they will be helping everyone. That’s why Holistic

Management is an individualistic revolution that helps communities. I

am excited to be a part of this revolution. I know that my individual

efforts will, in a minute but measurable way, improve the world for

all people.

As I see it, my part in this revolution will be to help others see

what I do. But how will I accomplish this? The same way one eats an

elephant (or so I am told), one bite at a time. My current bite is

centered on the family ranch. I am managing two hundred of my

own goats along with the family cattle, and hope to add sheep soon.

I hope to create a single mob from the three species, so that I won’t

have to triple my labor to triple my stocking rate. For now, this is a

big enough mouthful, but later I hope to share my insights with

people.

I know that there is a large, and increasing population of new

landowners, most of whom have never lived on the land before. I

view these people as clean slates. They haven’t been conditioned

from early childhood to the old ways that have brought us to this

time and place. If I can be the one to draw some outlines on that

slate, perhaps I can show them that their land isn’t separate from

personal lives, or their bank accounts. If I can do that, and help them

practice Holistic Management, then I will have improved their lives,

and in turn they will have improved mine. That is the best part of

Holistic Management, and why I am proud to say that I am a part of

the Holistic Management movement.

—Tyler Dawley

An Optimistic Revolution in a Pessimistic W o r l d

extended family aware of what they actually

wanted from the ranch. They realized that

while the production on the ranch wasn’t

important to them individually, it did affect

their own goals for the ranch. Each

individual’s personal goals were in line

with the ranch’s main goal—to continue

on and spread its healing. The extended

family became committed to achieving this

because it was what they wanted and that

commitment was repaid in full with interest

and continues to this day.

Since the great cabaña building episode,

we have added a grass-fed beef enterprise.

The whole family is actively involved in

went up very easily, both physically and

logistically. Since all of the family members

knew what had to be done, they just did it.

There was no need for reminders, or guilt

trips. What would have been a nightmare

before our “holistic” meeting, became a

positive event in the family history. The

family came to the ranch for two weeks

to build it.

It took a little longer for the increase

in revenue to affect the business, but it

happened. We increased our charge per rod

from $15 to $75 a day, and were able to offer

overnight stays in our scenic lakeside cabin.

This increase tripled our yearly fishing

revenue. Fishing became our most reliable

income for the ranch.

What Holistic Management did here on

the ranch was quite remarkable. Our family

had never been one of great uniformity

of purpose. The “city members” never had

been so invested in the ranch. One uncle

designed the cabaña and provided the

tools. Another uncle spent two weeks at

the ranch helping to build it. And the man

who started it all, my grandfather, also

helped in construction.

That first meeting in August made my

Ruminations From the Second Generationcontinued from page 5

marketing the product, especially my aunts

in the San Francisco Bay Area. We see a need

for another family meeting to discuss issues

of succession, and know that the creativity

and energy of the family can develop

solutions to this sticky problem.

And so, I realize what Holistic

Management is to me. It encompasses all

that my family is—from the past through

the future. That fateful day when we had

the family meeting illustrates what exactly

Holistic Management can do for me. As

I plan to spend my life dedicated to this

ranch and its goals, I am assured that while

everyone has their different personal goals,

the main goal is the same for everyone.

Tyler Dawley recently graduated from

Claremont McKenna College near Los

Angeles, California, where he choose, or

was perhaps forced, to write a senior thesis.

He wrote about Holistic Management, its

philosophical background, and how it

affected the family ranch. This article is an

adaptation from that thesis, and it wouldn’t

have happened without the help of his

family, especially his sister, Valerie. He can

be reached at [email protected].

There was no need for

reminders, or guilt trips.

What would have been a

nightmare before our

“holistic” meeting, became

a positive event in the

family history .

IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 LAND & LIVESTOCK 7

LAND L I V E S TO C K& A Special Section ofIN PRACTICE

MAY / JUNE 2001 #77

continued on page 8

The Chico Basin Ranch is comprised of 87,000 acres (35,200

hectares) located 35 minutes southeast of Colorado Springs,

Colorado, in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. The ranch is owned

by the state of Colorado, and has a rich ranching history. In 1999, with

the lease up for renewal, the Colorado State Land Board extended a

request for proposals to potential lessees asking them to address three

components—traditional management, education, and recreation.

My partners (Box T Partners) and I had long dreamed of operating

a large, contiguous ranch such as the Chico Basin, and we submitted

a comprehensive business plan detailing 1-year, 5-year, and 20-year

projections. We formed a diverse team to support our effort,

composed of the Colorado Bird Observatory, our banker, businessmen,

cattlemen and other associates. We received the support of a great

number of people who provided many ideas and inspiration, for

which we will always be thankful.

The State Land Board Commissioners concluded that our vision

for the Chico Basin gave us an edge over our competition, and they

awarded us a 25-year lease, which began November 1, 1999. This

vision has since been refined into the Chico Basin holistic goal,

which is pivotal in guiding our activities and decision-making.

Ecological Dive r s i t y

The ranch is composed of three ecologically distinct habitats:

short-grass prairie, sand sage prairie, and riparian/wetland corridors.

The short-grass prairie component is dominated by a diversity

of warm season grasses and scattered cholla cactus. Cool season

perennial grasses are scarce due to decades of season-long,

uncontrolled grazing. The sand sage prairie includes taller growing,

more productive grasses and a diversity of palatable forbs. Chico

Creek and Black Squirrel Creek meander through the ranch, creating

Chico Basin Ranch headquarters.

The New Ranching Economy—

D i versity and Creativity on the Chico Basin Ranchby Duke Phillips

From the EditorI am pleased to present the work and writing of two good

friends in this issue: Duke Phillips and Tony Malmberg. Duke and I

met at a Colorado Branch summer meeting in 1992, and have stayed

in close contact ever since. He has been one of my primary mentors,

imparting much valuable advice and wisdom over the years, both

professional and personal. After spending ten years at the Lasater

Ranch, Duke recently embarked upon a new challenge. He

secured a 25-year lease of the state-owned Chico Basin Ranch, on

the high plains of eastern Colorado. After only a year and a half of

management, Duke and his crew have pulled off a list of successes

affirming Duke’s affinity for getting things done and turning dreams

into reality. This July, another of those dreams will come to fruition as

the Chico Basin hosts a three-day celebration of Holistic Management.

For those planning to or interested in attending, the following article

on The Chico Basin should definitely pique your interest.

I met Tony Malmberg last winter at the Colorado Branch annual

meeting in Boulder, and immediately realized I had a lot to learn

from him. Tony and his wife, Andrea Brandenburg, ranch on the

cold sagebrush steppe of central Wyoming, and their accomplishments

on the land have been widely recognized. They, and partner, Todd

Graham, have developed a rangeland monitoring technique, based

on the Savory Center’s guidelines, they call Rangewise. The story

on Rangewise follows, along with Tony’s response to some of the

“Grazing in Nature’s Image” material that appeared in previous

editions of IN PRACTICE. Those of you ranching in arid brittle

environments should find his insights helpful and revealing.

But first, the Chico Basin Ranch.

—Jim Howell

a 25-mile (40 km) strip of plant and animal diversity. The Chico Creek

catchment is created by a unique geological formation that has created

a broad, sub-irrigated basin with hundreds of springs and small

streams. This is the most productive area of the ranch in terms of

plant growth and wildlife habitat.

Generating Profit in the Modern Ranching Economy

Box T Partners operates under the assumption that the business

of ranching is entering a new era. The American West is being

refinanced by individuals such as Ted Turner, large corporations like

Enron, and conservation groups such as the Rocky Mountain Elk

Foundation. The new owners’ interest is not

limited to agriculture and includes recreational

uses, habitat and species preservation, water

supply for urban consumption, and portfolio

diversification. Traditional uses of the land, such

as grazing cattle, are having an increasingly

difficult time financially. Although cattle will

always be an important income producer, they

will move toward the background economically.

Innovative business approaches will create non-

traditional enterprises that capitalize on inherent

ranch resources and the American public’s shift

of perception and concern for the well being of

the natural world and the health of the food

that is produced from it.

The modern day rancher is a business person

who views the “encroachment” of the American

public into what has always been the private

“domain” of the rancher, as reality. She sees this

encroachment as an opportunity, not a threat. He communicates as

well with the cowboys trotting their horses across the prairie as with

executives riding their Lear jets screaming across the sky. She knows

land and cattle and how to enhance her ranges ecologically through

grazing management, as her predecessors did. He understands that

managing a ranching business that encompasses the new public

presence and uses the land as a multifaceted resource, builds business

stability and profitability. The new rancher is not attempting to

change the American West and its long-standing traditions. He simply

realizes that ranching is continuing to evolve, and just as machines

replaced horses and wagons, traditional ways of doing business

have to change and adapt in order to survive.

At this point, our primary income-generating enterprise is a herd

of 1,800 brood cows, grazed on contract for several large western

ranches. We provide full year-round care for a set animal-unit-month

fee. Because Box T Partners didn’t want to go into debt, and because

we wanted to minimize our risk as we began this venture, having a

custom grazing service as our main enterprise fit very well.

Due to water limitations and constraints imposed by running

cattle for several different owners, our control of grazing and animal

impact isn’t what it needs to be for optimal movement toward the

ranch’s holistic goal. We’re doing the best we can, given present

circumstances, and have been able to control time to an extent, with

good results, but we have a ways to go yet. To that end, we began to

implement the first phase of our land plan early this year. We

identified the weak link in the cattle enterprise as energy conversion.

This means we need to get better control of the time plants are

exposed to grazing animals in order to trap more sunlight, and to

create more effective animal impact as we strive to improve the

effectiveness of the ecosystem processes.

We grow our best grass in the sub-irrigated basin bisected by

Chico Creek and in the sand hills, so that is where we are beginning

the implementation of our land plan, starting with the construction

of 15 miles (24 km) of one-strand electric fence

and 5 miles (8 km) of new 2-inch (50 mm) pipe.

We’ll be adding 60,000 gallons (240,000 liters) of

new water storage capacity to several existing

water points as well. Our plan is to eventually

manage all the cattle in one herd by loose-

herding them in a migratory fashion from water

point to water point (with very little fencing).

This year we have added another grazing

enterprise on the irrigated center pivots. Last fall

we planted a triticale/annual ryegrass mix, and

this spring we will stock up to 1,000 yearlings.

We have developed the pivots with one-strand

portable electric fence. Our aim is to maintain

high vegetative quality, which means reducing

recovery periods to as short as 21 days at the

peak of the growing season. Over time, we hope

this type of grazing management will increase

organic matter in these traditionally farmed soils.

We also have 125 acres (50 hectares) of side-roll and flood

irrigation. On 50 of these acres (20 hectares), we plan to develop

high-value crops such as Christmas trees, grapes, fruit trees, berries,

and asparagus, but slowly over time. We’ll also develop some high-

value wildlife habitat on this spot in an attempt to attract quail,

pheasant, doves, and turkeys for our upland bird hunting enterprise.

It is our intent to use a high-value resource—water—to produce

high-value products, and I think that means we have to stay away

from raising livestock feed crops.

Other income-generating activities include a cowboy camp and

two guesthouses that cater to adventurous individuals and families

who want a genuine ranch experience/vacation. Eventually teepees

will be added out on the open prairie, reminiscent of the bands of

Cheyenne Indians that once camped in this area. In addition to the

upland bird hunting, we also offer mule deer, whitetail deer, and

pronghorn hunts to serious, family-oriented outdoorsmen.

Our future plans call for developing a unique beef and organic

vegetable restaurant on one of the ranch’s most scenic lookouts. The

restaurant will operate seasonally, and will consist of a log pole and

beam structure covered with a giant tarp—safari style. Guests can

enjoy the 360-degree view of the prairie, with the Rockies and Pike’s

Peak towering just a few miles to the west. We plan to serve food

8 LAND & LIVESTOCK IN PRACTICE #77

The New Ranching Economycontinued from page 7

Duke Phillips

IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 LAND & LIVESTOCK 9

produced on the ranch and in the local community,

harvested directly from our cattle herd and from

organic gardens. Guests will park out of sight of

the restaurant, and will be shuttled to their tables

on horse-drawn wagons. The area surrounding the

restaurant will have hiking interpretive tails that

lead to the lake and nearby pastures. Eventually,

we plan to combine this facility with a ranching

heritage center that provides historical background

on this area and ranching in general. It is this type

of diverse enterprise mix, capitalizing on a ranch’s

unique set of resources, that will be the key to

profitability in the new economy of western

ranching.

Reaching Out to the Community

The Chico Basin Ranch is forming working

relationships with conservation groups such as the

Colorado Bird Observatory, The Nature Conservancy,

neighboring ranchers and local members of the

community to establish education programs and

community events. After our first year of operation, we have been

able to interact with a broad range of community members and

have become involved in a variety of outreach programs.

We held a Christmas bird count in December 1999 with the

Colorado Bird Observatory (CBO), and last May the ranch, along

with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and CBO, hosted naturalists

and scientists from the Colorado front range in the first annual Bugs,

Birds, Beast and BBQ Festival. We initiated a preliminary baseline for

flora, birds, invertebrates

and mammals. The day

culminated in a barbecue

that all our local

neighbors were

invited to attend.

Last summer the ranch

hosted the Colorado Bird

Observatory’s “On the

Wing” program, an

ornithology camp

attended by youth

from across the country.

In August, a range

monitoring workshop,

lead by Charley Orchard,

taught participants how

to establish a baseline

monitoring system to

track trends in the health

of rangeland ecosystem processes. Last winter we sponsored a Holistic

Management workshop taught by Kirk Gadzia that attempted to use

the Holistic Management™ model on real life situations. Additionally,

we have hosted several seminars for teachers who wish to use the

ranch as an educational opportunity for their students.

Other activities have included a Boy Scout Council meeting

involving 400 boys from across the region, and our first Artists’

Gathering where painters, printmakers, photographers, and sculptors

came to work on the ranch for several days. Their work was

assembled into a traveling exhibit that began on the ranch last

October and went on to hang at the local school, and the State

Land Board Office in Denver. Funds raised through this project

have been used to support a local community park.

The Chico Basin Ranch is a learning site for ranch managers

interested in the challenges and opportunities of ranching in the

modern world. Two managers, Jeremy Gingrich and Jeff Gossage,

are currently enrolled in this program. They have agreed to work

for a minimal salary in exchange for an experience-based education,

where they learn through hands-on, day-to-day ranching and business

activities that hold them accountable for realizing business goals.

This enables the ranch to employ highly motivated and committed

individuals while simultaneously keeping costs down.

After five years, employees like Jeremy and Jeff will possess

the skills necessary to help ranch owners develop their resources

following the model we are creating here, or take management

responsibility for an enterprise of their choice on the Chico. The

ranch also employs individuals and takes in interns from non-

ranching backgrounds. One current employee, Sherrie York, is a

naturalist and an accomplished artist, and her communication skills

and non-traditional perspective are proving invaluable in the ranch’s

education and community outreach efforts. Avi Perry is this year’s

intern. Originally from New Haven, Connecticut, he is presently

enrolled at Yale University and will take the lead in ongoing

writing and research projects in the office.

We are working on a daily basis to find viable ranching

and land management practices that build upon our western

heritage and that restore and enhance our fragile natural world.

We welcome your participation in our work, whether it be by

letters with ideas or by coming out to the ranch for a visit.

Please let us hear from you.

Duke Phillips is Chico Basin Ranch Manager. Contact him at

719/683-7960, email: [email protected], or by writing to:

22500 Peyton Hwy South, Colorado Springs, Colorado 80928.

The new rancher

realizes that ranching

is continuing to evolve,

and just as machines

replaced horses and

wagons, traditional

ways of doing

business have to

change and adapt in

order to survive.

One of seven spring-fed ponds on the ranch.

s a kid growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, my enthusiasm and

love for the Rocky Mountain West and the ranching way

of life permeated the core of my being. A variety of

circumstances prevented me from experiencing this life for much of

the year. At the end of every summer, I was banished from my high

country paradise and forced to return to the concrete madness of

southern California. For nine months of every year, my soul yearned

for the mountains—our creek full of brook trout, my horses, our

aspen forests and grassy parks. But without a doubt, those months

of displacement in the Los Angeles basin nurtured my love and

connection to the mountains. They forced me to be intensely aware

of what I was missing, so I don’t regret them. They also gave me

perspective that I wouldn’t have gained had I been a full-time

Coloradoan. I learned about the city and about

city people.

In the early ‘70s, one of our neighbors

began selling off one-acre (0.4-hectare) plots in

what would become one of the first mountain

residential developments that now fragment

much of the western U.S. landscape. The

people that bought those plots and built their

luxury getaways were all city people. I knew

the lifestyle and the environment from which

they were trying to escape, and I detested

them for transplanting a piece of that world

into my idyllic landscape. Now, almost 30 years

later, these urban transplants have displaced

much of the local knowledge and tradition that

once defined our western communities.

Many of our neighbors are now

city-based businessmen who have exchanged

phenomenal success in commerce for a piece

of mountain splendor. They have little idea

what to do with their new assets. They just

know that they are drawn here, just as I was as

a schoolchild living down the street from Disneyland. In that respect,

we share a common bond. And while I still have mixed feelings

about their presence, I certainly don’t detest them, and I’m willing

to make an effort to get along.

The towns nestled in the basins and valleys of western Colorado

have also taken on a new look. Cowboy hats and boots are still

common, but so are Goretex parkas and Birkenstock sandals. Beat

up pickups and stock trailers now pull up beside fancy SUV’s loaded

with kayaks and mountain bikes. These seemingly disparate segments

of the local population are all headed for the same place—the high

country, the former to work and the latter to play.

This is a common pattern throughout most of the West, and the

conflict that has resulted is no surprise. The old-time rancher and

logger, the ranchette owner who commutes to town to support his

mountain home, the absentee landowner who wants to preserve a

place for the elk to roam, and the town-based yuppie who lives for

her weekend hike—they all have divergent views of what constitutes

proper use of our western lands. The people down at the Bureau of

Land Management (BLM) and Forest Service offices, who administer

the public lands, are caught in the middle. But interestingly, all of

these seemingly opposing factions also share a common bond. They

love the land and they value a healthy, functioning, vibrant ecosystem.

C o n verging Diversity

Over in Lander, Wyoming, Tony Malmberg and his Rancher’s

Management Company (RMC) partners—Andrea Brandenburg, Todd

Graham, and Steve Wiles—have identified this rift and made the

proactive choice to try and heal it. Realizing that the only way to

create consensus is to focus on common ground, RMC has elected to

leave the squabbles and lawsuits behind and create a common

language that will bring these diverse interests

together. Since the common thread connecting

these groups is their interest in healthy land, this

common language must necessarily be land-

based as well. The RMC partners call this

language “Rangewise.”

Rangewise is a technique to monitor and

assess the health of the ecosystem processes

(water cycle, mineral cycle, energy flow, and

community dynamics). It can be implemented

on three levels, the details of which are

explained below. The monitoring results are

then employed in the development of sound

land use planning and decision-making. Its

vocabulary includes word combinations that

neither the rancher nor the environmentalist

nor the BLM range conservationist is accustomed

to using, especially not in each other’s company.

Andrea Brandenburg likes to say that this new

language integrates “emotion with data,” which

is important, since goals for the land are often

emotionally based.

Instead of arguing theory or opinion, Rangewise focuses on

19 “down to earth” indicators for deciding how healthy a piece of

land truly is. Many of these indicators (e.g., live canopy abundance,

litter incorporation, degree of soil crusting) are highly subjective, and

I asked if this was a problem. Other monitoring methods often yield

different results even when replicated at the same site on the same

day. Todd Graham recognizes this potential flaw: “We are aware of

the variability resulting from examining qualitative indicators and

use good communication with the rancher and the agencies to help

offset potential problems. However, they do crop up, because some

people place different weight on different indicators, evaluate

indicators differently, etc. Rangewise itself will not prevent

variation in judgment, but having a clear desired landscape

description will. We insist upon our client having a clear goal. If

that is established, then problems arising over subjective indicator

assessment can be minimized.”

According to Andrea, “When we were monitoring with some

10 LAND & LIVESTOCK IN PRACTICE #77

Common Values, Common Languageby Jim Howell

Tony Malmberg and Andrea Brandenburg

A

IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 LAND & LIVESTOCK 11

board members of a land trust in Wyoming, we had some variation

in the indicators but no disagreement on the time and timing of tools.

I personally don’t think we need exact data. What we need is for

people to:

• Learn to listen to what the land is telling us;

• Gather and interpret this knowledge together, on the land, and

allow for vibrant discussion on what each of us is hearing;

• Create a common (though not exactly the same) vision of the

land in the future; and

• Based on all of this data (emotional and scientific), develop land

management strategies so we can achieve our common vision.”

R a n g ewise Nuts and Bolts

Unlike the Holistic Management™ biological monitoring procedure,

which gathers a list of indicators in 100 random six-inch (24 mm)

circles within a constant sample area, Rangewise measures its 19

indicators along a set 200-foot (61-meter) transect, much like Charley

Orchard’s Land EKG. But unlike the Land EKG, which measures four

set plots along the 200-foot tape, Rangewise measures five (or 10,

depending on the situation) 9.6-square-foot (1 square meter) plots, each

one 40 feet (12.2 meters) apart. The first one is used as the set overhead

photo point. Photos are also taken from each end of the transect. The

19 indicators are assessed within each of the plots by scoring them on

a 0 to 5 scale, with 0 being the most undesirable condition and five

being the most desirable in terms of the goal for the land.

Orchard’s Land EKG data are graphically displayed on a linear Land

Eco-graph (see the March/April 2000 edition of IN PRACTICE). The

RMC partners also recognized the need to display the data in an easy-

to-interpret style, so they created the Range Web. According to Todd,

“the Range Web attempts to portray the interconnectedness of the

19 indicators and the four ecosystem processes.”

L evels of Monitoring

RMC has developed three levels of Rangewise monitoring to cater

for different needs:

Level I monitoring is designed to provide a quick overview of the

state of the ecosystem processes on any given piece of land. The intent

is for the parties involved to come to agreement on where the land

stands at a specific point in time, to assess the effects of past tools in

creating those current conditions, and to decide on future management

approaches to move that land in the desired direction.

Level II monitoring is designed for land managers who wish to do

their own monitoring. It requires no special technical knowledge and

gives a comprehensive picture of how the four ecosystem processes

Todd Graham Steve Wiles

continued on page 12

The Range Web looks like a dartboard or wagon wheel, with

the spokes corresponding to the 19 indicators. The edge of the circle

corresponds to a score of zero, while a score of five hits the bullseye.

The lowest scores tend to bunch along one section of the Range Web.

Since the indicators (the spokes) on each section of the Range Web

correspond to one of the four ecosystem processes, those undesirable

scores tend to highlight which of the four processes is/are suffering

the most. Specific management actions can then be prescribed that

are most likely to move that particular ecosystem process toward

the holistic goal.

A Sample Range Web

Center Circle (light-shaded) = FUNCTIONAL

Middle Circle (white) = AT RISK

Outer Circle (dark-shaded) = NON-FUNCTIONAL

Recently I heard Jim Howell speak in Boulder, Colorado

and I read his piece, “Grazing in Nature’s Image” in the

January/February issue (#75) of IN PRAC T I C E. His thoughts

on grazing/recove r y, rest, and animal impact provided me with

further understanding of how these tools impact different types of

brittle environments. They also helped me better understand events,

in hindsight, on our ranch in central Wyo m i n g .

E ven though we are taught to pay attention to the soil surface

for indicators of land health (in terms of the

ecosystem processes), I had become more

focused on the process of managing time and

timing and increasing stocking rates than

monitoring soil surface condition. Jim’s article

quickly reminded me that I was tending to

forget about the fundamental need to manage

for litter to cover bare ground in brittle

environments. I forgot to assume I was wrong!

As Allan Savory says, “It’s simple but

not easy. ”

A Litter Supply Problem

Jim’s article reminded me that the

definitions of recovery and total rest do not

change across brittle environments. Howeve r ,

the time required for a perennial grass to

completely recover from grazing varies widely depending on the

type of brittle environment. In the high rainfall brittle tropics, it may

take only a few weeks for plants to recover leaf area, root volume,

and sufficient new material to serve as litter. In a dry-cold steppe,

this might take years, depending on aridity.

This distinction was important for me to realize that I do, in fa c t ,

h a ve a litter supply problem. The more arid the brittle environment,

the more conscious we have to be to allow the plant to deve l o p

s u fficient new leaf area to not only feed the animals next time they

come through, but to provide for a source of soil-covering litter as we l l .

In a low rainfall brittle environment this may be one or more years!

When Has a Plant Really Recove r e d ?

The initial definitions of an overrested grass plant (ex c e s s i ve dead

plant material blocking sunlight energy to the

plant’s growth points) and a recovered plant (the

state when a grazed plant looks like a healthy

ungrazed plant) still apply. Jim’s observations

simply reassure me that these definitions are

adequate and must not be shaded or compromised.

I had convinced myself that a plant was recove r e d

if it headed out, even if it was only 6 inches (15 cm)

tall, while the ungrazed plant was 24 inches (60 cm)

tall. I had also convinced myself that a plant wa s

overrested if it contained residual standing

vegetation of any stature. Jim added to my

comprehension of these initial definitions of

overrest and recove r y. With this new

comprehension, I can more clearly understand

what has happened on our landscape in the

Southern Wind River Range for the past 10 ye a r s .

My Big Mistake

I attended my first Holistic Management Seminar in 1987 or 1988. It

took a couple of years to absorb and adjust. In 1990, we began to plan

our grazing and harvested 5,582 animal unit months (AUMs) of fo r a g e .

We increased stock density, reduced time and planned timing to

12 LAND & LIVESTOCK IN PRACTICE #77

Tony Malmberg

Monitoring with Open Eye sby Tony Malmberg

are functioning in a specific area over time. This in turn guides

managers in making sound decisions toward their holistic goals. RMC

gives seminars on Level II monitoring that provide participants hands-

on practice in selecting a monitoring site, setting up a transect, and

picking among the basket of land management tools. The sessions

wrap up with learning how to enter the data in the Rangewise website

(www.Rangewise.com) for data storage and a completed report.

Level III monitoring incorporates a series of further measurements

designed to yield an even more comprehensive and quantitative

picture of rangeland health. Instead of measuring only five plots

along the transect (as done in Level II), Level III measures ten plots.

Additionally, from every foot marker along the length of the 200-foot

(61 meter) tape, the distance to the nearest perennial plant is measured,

and the species is recorded. In one of the plots, the plants are cut and

weighed to yield a graph showing the predominant species and their

composition by weight. Graphs are also generated that show percent

plant species composition, ground cover percentages (i.e., percentage

covered by living plants, dead litter, or bare), and total forage

production per acre (extrapolated from cutting and weighing the

contents of the 9.6-square-foot plots). All of this data, including the

Range Web, is compiled on one simple summary sheet.

Level III monitoring was developed in response to the BLM

Standards and Guidelines, issued in 1994, toward which public lands

ranchers would soon be expected to manage. Ranchers were feeling

both afraid and defensive about these new standards and anxious to

find a method for documenting what was happening on their land in

a way that would stand up in court. Enter Rangewise Level III. RMC

currently has monitoring agreements with BLM offices in Wyoming

and Colorado that state that Level III data will be accepted when

making management decisions on federally-controlled BLM lands.

A Proactive Approach

Tony and Andrea are quick to point out that RMC’s focus is not to

Common Values, Common Languagecontinued from page 11

IN PRACTICE • MAY / JUNE 2001 LAND & LIVESTOCK 13

increase our stocking rate to 8,880 (59% increase) by 1993. In 1994 we

had the worst drought in the history of our county. We de-stocked

about 7% to 8,200 AUMs. The fo l l owing year our stocking rate was

9,200 and up to 11,000 by 1996.

From 1996 to 1998 I changed from grazing each paddock once

per year to moving faster in the spring to keep grass in a more

ve g e t a t i ve state, and then grazing again later in the season. My actual

use records indicate a direct correlation to this practice and less

production. The amount of decline seems to be directly proportional

to levels of utilization. This is when I began calling bluebunch

r e g r owth “recovered” when headed out at 6 inches (15 cm) tall, eve n

though the ungrazed plants were 18 to 24 inches (45 to 60 cm) tall.

At the same time, the Sandburg bluegrass and mutton grass had no

r e g r owth at all. I was confused about the declining production

because I knew I wasn’t rotating by the calendar. I reasoned the

problem could be that I was practicing the rotation of partial rest,

and I may have been (and still could be). But Jim’s suggestion of

not allowing sufficient recovery to both recover leaf area and

accumulate a source of new litter fit the cause and effect test.

Understanding What Went Wr o n g

The landscape we were managing had been season-long grazed fo r

a long time. We began deferred grazing practices in the early ‘80s. The

land consisted of overgrazed and overrested plants, in addition to ove r

impacted and overrested land. The land portrayed the classic symptoms

of too few cattle for too long of a time. By increasing stock density and

length of recovery periods two things happened. First, the ove r r e s t e d

plants with a year’s supply of litter were tromped to the ground or

consumed. Second, the overgrazed plants were allowed more time to

r e c over and this increased plant vigor. The entire equation benefited.

H owever, as we accelerated our planned grazing in 1996, I started

redefining “recovery” and “overrest” to accommodate continued

increased stocking rates. If we would have continued monitoring,

with open eye s, I would have seen that our arid, cold steppe landscape

takes longer to recover and much longer to begin suffering from

overrest than the more productive tropical environments that

spawned Holistic Management.

When our monitoring indicated that our bare ground stopped

decreasing, we should have realized that our production of new

litter-making material was inadequate. I didn’t pick up on this

because we did have less bare ground than before. However, it is

significant that bare ground stopped decreasing. The final punch

indicating we had a problem was declining plant yield.

When I ask if these problems are due to rotating partial rest, the

monitoring data indicates no, while a lack of a litter supply due to

inadequate recovery does fit the monitoring data. We didn’t need

more impact, plants needed longer to recover. Jim’s point that very

arid brittle environments “need animals the most, but that doesn’t

necessarily mean these areas need the most animals,” alleviates a lot

of mindless focus I have had on implementing the tool of animal

impact with herd effect.

S a vory’s Rule of Thumb

I am reminded of one of Savory’s rules of thumb: when in

doubt, plan for a longer recovery period . I may be rotating partial

rest and I may be using many tools wrong, but with longer recove r y

periods my forage production was not suffering, and bare ground

was decreasing. Jim reminds me once again of Savory’s mantra,

“Continue to monitor with open eyes!” As long as we had adequate

supplies of litter, due to fully recovered plants, we were improv i n g

land health. But when we began to graze each paddock twice per

year, we inadvertently used up the supply of litter, and we began

running into problems.

In summation, Jim says if “the result [of grazing, animal impact,

etc.] at the end of the year is an increase in soil cover,” that is the

yardstick. This indicates that sufficient recovery periods are being

planned to allow for the accumulation of enough plant material to

s e r ve as both forage for livestock and litter for the soil. This reminds

us of the entire point of sustainability. All life on our planet suspends

on a fragile filament called “soil.” Eternity’s point of reference in

measuring our legacy will be relative to the strengthening or

eroding of that filament.

gather data for the sake of winning potential court cases. Instead, they

emphasize two things to potential clients. First, they insist that the

client acknowledge that the Rangewise data will most likely indicate a

change in management will indeed be necessary. Second, they insist

that the rancher develop a goal to manage toward, and they strongly

encourage the inclusion of a broad perspective of interests in forming

that goal.

They expect the public lands rancher to be willing to develop

the goal along with the input of a healthy cross-section of

interested community members. If the client is not on board on

both of those counts, RMC feels they are treating symptoms

rather than addressing problems and wasting their time and the

client’s money.

Tony insists on giving Todd credit for guiding a “recovering

linear thinker” (Tony) to think holistically. “In addition to being our

anchor in holistic thought and decision-making,” says Tony, “Todd

is our bridge between communicating holistic thinking well to

academia/agency folks. Andrea is our bridge between

environmentalists and holistic thinking. I am our bridge between

more traditional ranchers and holistic thinking. Together, we are

designing Rangewise to bring all of this together.”

Coming Together on the Land

This brings us back to where we started, with the new

demographic profile of the American West. Until this “broad

perspective of interests” starts to meet out on the land, and discuss,

analyze, monitor, dig, scratch, and smell the earth together, we

will struggle to find common ground. For these meetings to be

meaningful and productive, each interest must realize that we all

want, and in fact need, the same things. We need a covered soil

surface, a diversity of healthy vibrant plants, clear perennial streams

and rivers, and abundant wildlife of all forms. These are the things

that bind us, but we need a common language to help guide us in

our efforts to strengthen that bond. Thanks to the work of people

like the RMC partners, this language is evolving and spreading

across our brittle western landscape.

Tony Malmber g can be reached via email at

[email protected], or by phone at 307/332-5073.

14 HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE #77

NE SARE Funds Holistic

Management Training

The Northeast Sustainable Agriculture

Research and Education (SARE)

Professional Development Program recently

awarded a $143,500 grant to the South

Central New York Resource Conservation

and Development Project (SoCNY RC & D).

This grant will fund a collaborative three-

year project that will train and certify 10

Cooperative Extension Service Faculty and

NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation

Service) field agents to teach and facilitate

Holistic Management processes for Whole

Farm Planning in the Northeastern U.S.

This is the first Certified Educator Training

Program for Holistic Management in the

Northeast, and the Cooperative Extension

faculty and NRCS agents will be joined in

this training by individuals who work for

nonprofit agencies in the Northeast that also

serve as a resource to farmers in the region.

Participants in this project include: the

Cooperative Extension Services of Cornell

University and the Universities of Vermont,

Maryland, Massachusetts and New

Hampshire; NY State NRCS and RC & D;

the Allan Savory Center for Holistic

Management; Consortium for Sustainable