0040,41440100!iit0OHI:*' ,i*, ,*00! ;' ,*00.440,44404, · tin10141114 $61660 'Mg* 6 * prom *wind...

Transcript of 0040,41440100!iit0OHI:*' ,i*, ,*00! ;' ,*00.440,44404, · tin10141114 $61660 'Mg* 6 * prom *wind...

ii000#4101*.ii*

11100t1

''''0040,41440100!iit0OHI:*',i*, ,*00! ;' ,*00.440,44404,

1111M1=

41111111WO

MM

I.LIV

IIM_ U

LL

AI

_

041000100

Ompoloo00110

0*

ON

4101041k 11004,000041400-10mo000

40100: 1001000004mosst***110

4$0,10"4 1004004011010'***".

04000wissi0040#000000iipposiNowli'

41104.0101*

4

rn

Yrr9,01

.0001041

v-

91E:MIT 430$

101001/lit ,

P.P1,A41

rif

"WV

I

rrr !Mr

,r711.1r111/rrorr

imPOPIN+4/1440

TTY'S

r1TrW frrrr441'

1

11rrrn

rrrrarrrr

,rrr,

rwrrrrpfmstv Tr

rrr rpr

rr.frrrr imrsforr

rry P4044410

t+Sti.

rrTfr

'4111*

.r.,r1rf

res

I- 'IS* 400

- ^111111

rinpimp,

I.

IØi . itto 4464.44116,

It* Wink& me 66011

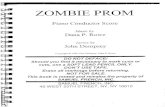

* OW tostiotino 01160 flioSiwo OwaniOtk $1110100114

etenn, *now I* *Odom Mt **I tin10141114 $61660 'Mg* 6 * prom *wind *Op 0. 16. itinositootanil IOW 4110,1114911* 9161011i 01100014W,

WM** SLOVW,4 A '14

einterittits ottlitoslif pessitles eeto eetteed esa lbonnisi iNS COW

me* odensta, pobltsking 111400101116° fika, Otasiesity

SAW IMenolise Ateseintiom and *WA Wow L Staselley, Met,

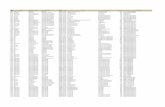

401191$, the tonadatt'st. od *Ms a yea* woolkshop le old &we Otero as Alison and Flo-

Mao ad prosides inronke train* am* 616eal werfahopa, The cow tosolly *Mob dui are put of the Mott

pennreet ate more intemsted in corn.

netolty involvement than In control,

tiftkft to left to the established boards of

edocation. Is both Miehliput and New York, let

bastion now gnats a degree of authority to local school boards. Other states (Cali- fornia and Massachusetts) and cities (Ca-

ry, Dayton. Washington D.C., Philadel-

phia) aro considering proposals for great-

+1116110

*06 de* eadi MIAOW MI nem ibtn Denali It Cake

Diseettitt 660 "lbw

stoot SI arms to that sailer oommosity

noweed t, lb. ntrospfertre mod mem et dep saloask meld rem iseinove. falarffillf*

!Jowl nooted oceordie to Matio Rte. mod seiras lose Illblionesphyli, pro.

1116"isSies a fiessetnoh foe chow costroll abers basic

power mot tileperke mum!. son aeseopanot mew panidpents le die olsastiosal proem may lick beck- owe* is odematiossi thew end prec- tiort. bet this doce oot prevent them from *Mee relentlowly to the oar* of Nada- mavotal *WO in school policy. . . a Com-

amity costrol, to the extent that it follows democratic precedent% caw* Its own seeds of renewal, Its eery mason for be-

ton, it mut be remembered. is as a reaction to rigidities and unresponsiveness.

Morgan Comma* School

The Morgan School is located in the northwest section of Washington, D.C.,

in what was once an affluent neighbor- hood of large, well-kept homes. Over the

years, these homes have been converted into the crowded rooming-houses that characterize the area today. But because it retains a substantial number of one-

family homes, the Morgan neighborhood is still considered one of the "better" res-

Mods! mos. Mee the Supremos CorotMed in 1934 dist solstice in the pubabc schools was unconstitutional. manywhite reeklents hove trensfenbg theiral_kirken to private achook Tire attend-awe at the Morgan public eleineataryschool became 96 percent black and 90percent poor. Crowded conditions in theschool steadily worsened so that eventhe auditorium had to be used for chasmLower grades went on half sessions, andchildren could no longer be registered inkindergarten. Books. equipment, and ma-terials were poor and in short supply.Meanwhile, in many all-white neighbor-hoods, schools were only half full.

In 1954, animosity between white stu-dents at the nearby Adams School andblack students at Morgan erupted into arock-throwing incident that resulted in aserious injury to one c' the children. Theprincipals of the two schools were gal-vanized into action; children and parentsfrom both schools met and discussedways they could improve the atmos-phere. Out of these meetings grew acommunity effort created through block-by-block organization: The Adams Mor-gan Better Neighborhood Conference, aracially and economically representativegroup.

In 1956, the Conference applied for afederal grant to develop neighborhoodparticipation in community improve-ment. The grant was given in 1958 underthe supervision of American Universityas part of the urban renewal program.Block and local business groups formed

1

the Adios Mows Planning Cowndifts,as& topthei with proksolowal plow"they proposed changes to improve rest-andel and shopping arese, rerouteheavy traffic to main arteries. and pro-vide (Wettest paridng. Early plans alsoincluded a new building to replace theOS-year-old Morgan school. as well as ad-ditional play and recreation areas. Butafter numerous meetings, surveys, re-ports. and an enormous input of profes-sional and volunteer time, the proposalwas shelved. No clear explanation wasforthcoming, and the proposal is still onthe books.

In 1985, people from the block groupswho had not dropped out of communityactivities looked for more volunteers tojoin them in the Adams Morgan Com-munity Council, now incorporated, Aflyer written and circulated by a neigh-borhood worker listed the Council'sareas of interest: school, summer camp,and a medical program. According to theleaflet, "No Urban Renewal is involved.Just a community trying and wanting tolive together." Drawing in as many resi-dents as possible, the Council discussedreforms and enrichment programs thatmight be introduced into the economi-cally and racially diverse neighborhood.

By this date, the disintegration of edu-cation in all Washington public schoolswas generally recognized and deplored.In particular, the tracking system, intro-duced in the high schools in 1956, cameunder serious attack. Many communitypeople were opposed to tracking as un-

40

,ijotaciontic, They saw It as a means of~lotion. When Sepertntendeat CadWoes extended tracking to the butlerød elementary schools, a kgal bade

eospted in which black militant JuliusHebson challenged tbe Board of Ednca-On and the superintendent. (The case,Hobson. vs. Hansen, was adjudicated intiNor of Hobson in Tune 1907, and track-10% was bald to be discriminatory spinalNegroes and the poor.)

In an effort to find substitutes for thecontroversial tracking system hi MayOno, Dr. Hansen and the Board or Edu-Otion proposed that a study of D.C.sclools be made by Teachers College ofColumbia University. The study resultsAna to be known as the Passow Report.64 named for its director, A. Harry Pas-s4w. professor of education at TeachersCollege. Among the findings were: a lowlevel of scholastic achievement, a cur-riculum not especially developed for orgdepted to the urban population it served,increasing de facto residential segrega-tion resulting in a largely resegregatednhool system, and poor communicationbetween schools and the communitiesthey served. The report stated:

The starting point for good teaching is therecognition of differences, of learning dis-abilities, whatever their causes or origins,of individual talents and unusual potentialfor learning, of hidden aspirations andcommitments . . . New concepts of urbaneducation are demandednew policies;different arrangements of time, organiza-tion and space; more effective deploymentof staff; an extended role for the school in

Ohm emesammeitya a istaisposi oerManiewiisgsmisima imianediena emstisemisi awlsummit Limas el seppanite meivites,

Thee la no evidence that apnea pm.meals or recommendations were follow .ed through. except in isolated Inalancse,and these way have been unrelated tothe report.

The campaign foe Morgan School im-provement was revived by the Board ofEducation's announcement that all ele-mentary schools would go on double sea-sion. One concerned parent. Mrs. VeraStevens, recalled what happened. in anarticle in the American Teacher:

gut involved when Harry went to kin-dergarten. He had done well in preschool.but he started to have a lot of trouble. Hisclass was overcrowded, It had more then35 children, and four classes were beingheld in the auditorium. The school admin-istration announced they were going toput the school on half-days . . parentswcnt downtown and talked to the assist-ant superintendent for elementary schools.We told her there was room for children inCook and Adams school, but she said itwould be a lot of paperwork to transferthem, and they would have trouble adjust-ing. We told her the children will adjustfine, although it might be harder on theparents and the administration. I told her,'My God, we'll stay up all night to do thepaperwork, but we don't want these chil-dren cheated.'

After that, our school committee beganto work with the community council, andour strong block groups got started. Thiswas a forgotten school. The teachers hadno equipment to work with, the parentshad no say in what went on ... The boardof education and the teachers were doling

ow Woo Woman to dim kals, Stowedto we ht. they Atka este Ittatbies toete.hose atot *rag* passed the day. Thenthey twat sa their ketely hams is theta-tabs or tar away to the& children who eato pita* *chock,

The parents turned to tbe °immunityCouncil for help. At this point the Coun-cil was dominated by young white lib-ends who had moved into the commu-nity. Many were professionals interestedin finding an integrated experience fortheir children, and some were anxiousto become politically active. Among theCouncil's most influential while mem-bers were: Harrison Owens, Council di-rector, Irene Waskow, an attorney mar-ried to Arthur Waskow, a resident fel-low at the Institute of Policy Studies,Marcus Raskin, the Institute's co-direc-tor and a trustee of Antioch University,and Christopher Jencks, a teacher at theInstitute. Among the black representa-tives were Marie Reed, an influential andenergetic leader in the community andBishop of the Sacred Heart SpiritualChurch, Mary French, the present schoolboard chairman, Edward Jackson, vice-chairman of the board, and Vera Stevens.

In March 1966, a group of parents metwith the Board of Education and the dou-ble session plan was rescinded. With ataste of success the parents decided toset themselves a higher goal: to establisha truly integrated school that would pro-vide quality education. A quality schoolcould be created, they reasoned, by uti-lizing some of the local people with good

11

odonationai Mew serialei the unkmesi.sailve cunicrahem and institating a °can.amity controller orpanization. The ideaeePleseated a chew and blank parentswet* in favor of change. They were die.satisfied with the inadequate facilities.They wanted better education and bettertreatment for their ddidren, and morerasped for themselves abort they visitedthe school.

The Council called a number of gen-eral meetings, which were action meet-ings concerned primarily with gettingsignatures for petitions. There were oth-er meetings with interested parentswhere goals were worked out. Councildirector Owens observed that "one ofthe things that came out extraordinarilyclearly was that the temper was conserv-ative. All of the things that people wereasking for were what every good schoolshould have."

The parents and community peopleknew they needed professional help, andthey decided to seek a contractual rela-tionship with the Board of Education. Itwas suggested that the board was morelikely to listen to a plan if a "respect-able" party, such as a university, wereinvolved. Antioch College was recom-mended because there were importantalumni residing in the community andbecause the college, whose main campusis in Ohio, has a graduate school of edu-cation, Antioch-Putney, in Washington.Antioch-Putney already had one teachertraining program and might be interestedin another in a D.C. school.

CHAPTER N

1161:x4444441 gici4401

I 4--

it was in dis eettint-whlie the Hoboesvs. Hawes Week was patties andwhile the Poem study was undermy--.that Harrison Owes& and Christopherleads of the Community Council metwith Monis Keeton. acedemic vke-pres-idiot and dean of the school of educe-lion of Antioch. and Superintendent CarlHansen in January 1967. At Ibis time Dr.Hansen showed Interest in the idea onlyu a demonstration project. He made ltclear that the experimental school couldexpect only its normal allotment offunds, and he urged that Antioch deter-mine the objectives and the curriculum.

Psior to the Antioch involvement, asmall, active segment of the communityhad worked out the specifics of thechanges they were seeking. HarrisonOwens has commented, "One of the firstproposals or descriptions of the schoolwas written by Mary French. Mrs. Frenchat that time was scrubbing floors in theSenate office building. When she gotdone scrubbing floors she read every-thing anybody had on education." Outof this she put together a proposal whichinspired a lot of interest in the com-munity.

The Community Council and the par-ents wanted to select the principal. Theywanted area residents employed as teach-

er aides to improve the teacher-pupilratio. They wanted a school that was in-tegrated both racially and socioeconomi-cally. They wanted more creative teach-ers who wanted to teach at Morgan. Theywanted a more effective counseling pro-

imui I. Ihis settitil-whde the Hobosvs. Hama Walt was parkas trdwhile the Resew study ma uademay-that Hanlon Owens aad Chdskopherlochs of the Community Mandl ms4with Monis Keeton, academic vloe.pree-[dent and dean of the school of educe..lion of Antioch, sod Supednleadent CarlHansen in January 11167. At this time Dr.Hansen showed intend in the idea onlyas a demonstration project. He made itdear that the experimental school couldexpect only its normal allotment offunds, and he urged that Antioch deter.mine the objectives and the curriculum.

Prior to the Antioch involvement, aBMW, active segment of the communityhad worked out the specifics of thechanges they were seeking. HarrisonOwens has commented, "One of the firstproposals or descriptions of the school

was written by Mary French. Mrs. Frenchat that time was scrubbing floors in theSenate office building. When she gotdone scrubbing floors she read every-thing anybody had on education." Out

of this she put together a proposal whichinspired a lot of interest in the com-munity.

The Community Council and the par-ents wanted to select the principal. Theywanted area residents employed as teach-er aides to improve the teacher-pupilratio. They wanted a school that was in-tegrated both racially and socioeconomi-cally. They wanted more creative teach-

ers who wanted to teach at Morgan. Theywanted a more effective counseling pro-

geim ie bds hemp aid wiled tosather.They mated hos of as Imaarele OW*phere for the claim for example, kwas spadkdly meutlowed at commtaitymettles, that children should be allowed

lo go to the bathroom Moo necessaryand spend a pan of each day outdoors.

The idea of freedom and activity would

labs have more than one interpolation.Mr. Owens. MN of the conservatismin the community, believed that somethings. such as "discovery learning,"should not be introduced right away.Janette M. Turner quoted him:

Tha fact that you may also learn whenyoulit having fun, sometimes doesn't getacrou. There's an expectation that parentshave for what their kids are going to getand if they aren't sitting down ... and ifthey don't do such and such, they obvi-ously aren't in schoolregardless of thefact that there is learning going on ... Frominitial conversations with Dr. Keeton, righton through, I kept trying to emphasize ...that everybody involved should keep it inmind that this was a community schooland not a community school. That thingshad to derive from the community. Thatcurriculum changes could never get aheadof where the parents were. And if it wasapparently happening this way, then theanswer was not more and faster, but lessand slower, with an enormous amount ofeffort thrown into dealing with the parentson a block by block basis, involving themin the afternoons and the daytime in whatwas happening in the school, so that youcould begin to develop a group of peoplewho could be the spokesmen, withoutwhite faces, and very much in the heart ofthe community.

In order to preside babies foe slimiestbathers sod $o stay "ildda doe okraboard's allolment of fends. Aatioth pro-posed a oil of professional blathers aswell as colkse and community intone.Ilda plan would Wow the redo ofadults to papas and provide a favorablecost-benelit ratio since Intents would bepaid less than professional teachers. Alsosome tuition money paid to Antioch byInterns would revert to Mow* to payfor admielsinators and services. The dif-ferentiated staff was a major experimentin the projectint attempt to move to-ward quality education without substan-tial [nemeses In personnel costs. Antiochalso favored a limited project: Dr. Kee-ton, like Dr. Hansen, was thinking interms of a demonstration unita smell-sale program would be a realistic com-mitment for the college and would allowfor testing and experimenting beforemoving into a full-scale school situation.

During the planning phase, Dr. Hansensuggested to Dr. Keeton that the Councilwas not representative of the parents; hewondered if Council members' liberaland radical notions of education were inline with the views of most parents. Asa result of his doubts, arrangements weremade for the community at large to electa school board.

The final agreement between Antiochand the board called for a demonstrationschool with a new staffing plan, an ex-perimental curriculum to be developedby Antioch, and an elected school board.Some of the people who had done the

13

pl.** and nerds** woald be to.placed by Ales wbo wool!! Impleamratthe proven; all stall meld be milkedto reapply for *de jobs: sad Antiochwould appobit a reduced umber ofteachers subject to approval by the Bondof Education. Morgsn School would con-tines to get only its usual allotment offunds from the (Mkt Antioch wouldpay the cods of its towhee 'dynode*program and seek any supplementalfunds needed. The superintendent pre-sented the plan to the DC Board or Edu-cation, and it was approved in May 1967.

Some emblems

To get the project started, a number ofconcessions were made by college andcommunity both. Antioch favored a dem-onstration unit and a year and a halfpreparation time. Community peoplewanted total school involvement by theSeptember term which was only monthsaway. Antioch yielded, and a Septemberopening date was planned.

In the interest of expediency therewere no formal contracts or agreementsbetween the Community Council and An-tioch, and so roles were not clearly de-fined. The school was operating withouta principal because he, like some of theteachers who had not had a voice in theearly planning, chose not to reapply,Leadership was neededfast. A projectdirector who had no previous connectionwith either Antioch, or elementary, orghetto schools was brought in and ac-

opted by the commooky boom of hisavailability and the4t dein to igul OM.ed, Pad Luger become the Mei admin.Moder, ead OW of the dodikasealetog, from conks's* to bolkflog OWN*MIKA was kit to him by ddauk. Somecommunity leaders rimed thole effortsout of fagot mid the realizatkaa that acommiudipoleded school board wieldsoon replace them others who were op-pointed to committees, such as the an*riculum committee, found that they couldnot function effectively for lack of tech-nice) knowledge and direction. Becausethere was no one else. Mr. tauter triedto "do everything." and there were thosewho. unaware of the circumstances, Mthe had overstepped his bounds, andthey criticized Antioch for poor plan-ning.

New Inexperienced Staff: The differen-tinted staff plan required the eliminationor some teachers so that more Antiochinterns could be brought in, and therewere comments from teachers and par-ents that white interns were pushing outblack teachers. According to Mr. Lauter,"It was a correct perception . .. becausethe interns were predominantly white. Itwas obvious that we were bringingwhites in and, in fact, we were pushingsome of the Negro teachers out."

Furthermore, the differentiated staffcalled for two categories: "executiveteacher" and "associate teacher." It wasdifficult to get experienced people, par-ticularly blacks, to be associate teachers;

go* hun pty.4 diow assalistasaw tbs othakookip as a boasitkallissmosh Odor Mains wet. opposollpPissossadas mad MON is poemastpreksorod iloche rs. tbaso ow nowresiosadoot, Accomdiog to Mr. West'Vim school aimed so bet Mind of17 relalkely expansocad *saws, odyabout eke (plus two Notified ThawC01118 asparvison4 in the whok schoolof 730 children. Only three of these wereholdovers from the previous faculty."

Inadequate Preparation: As pert of tlwAntioch plan to set up teacher traininginstitutes, a workshop was planned forAugust. Teacher* and interna txpectedthat since time was short, curriculumplanning would get top Madly. Mr. LBWtot, whose background was teachingEnglish literature and organizing for Stu-dents for a Democratic Sodety, put thegreatest stress on solving the problemsof whites working in a black community.In a memo to Dr. Keeton, he wrote, "1think there are a number of things wecan go into the year without, but I thinkwe must begin to shake teachers loosefrom their traditional restrictions, andbegin to build a unity of purpose." As aresult of his emphasis on sensitivitytraining and the hiring of staff memberswho had worked in freedom schools inthe South, the summer workshop wasprimarily concerned with black-white re-lationships. Some of the participants,particularly the community interns, wereshaken and confused by the frankness of

160

tie Eimutsiews Olheek elliesist d ilealiter lea the um&Asup sem wisdikeespstimmeet Ia Wee dIkmeis Ohmmom kWh* mptewiees of tie geedfar *Um wade" mmi lam IOW with.ed dear *beim of %Ad detee

lipostautly no4 MIMIC. VIMmeatimed I. comedies with mettes .boa bet dew woo so acted rentookm*Wm Both teethed' sod iikKIKessey witheet my previous teschiesprime. west left the new school yewnot lamming how or what they were toInch cbildres, Meanwhile, the comma.shy people began negotiations to hire aMack pdodpal, but he had so put le theworishop or the opening days of school.

Freedom versus Suydam: Aside fromthe dialogue on rice, the concept of"freedom" was examined during thesummer. To Mr. Lanier. freedom had todo in part with educational ideas, sudsas those used in the British InfantSchools. To Dr. Keeton, it had to do withstudent teachers and their relationshipwith professors who "should not andcannot effectively tell the teachers (An.tioch interns) what to do in the school.but can only assist the teaching staff todecide upon and carry out their own con-cepts and implementations of an im-proved program." Another view of free-dom was that of a teacher corps student:"Antioch wanted you to do your ownthing. But in a school everybody reallycan't just do his own thing. There haveto be some outlines to go by." One teach-

/7

ye *skeet it* dies Illid I SW ewe.ed el the immilsioup eel WO WI Ismdito CM* et brestem fah &I weNSW isee week sired fermilses Ws weeeOMNI* to Wit* illiiikodso ebb pwpie 5141111 hr Obit Mika did theysemi mliketis the eshousis whom liheywen 00 $40be witat ems NSW kwdwir Mims Mkt mat ham bum paPtkuisrly Wei hofdmessesdna is this sem who we the Nerochildroe Another tescher snld "It lespreexisted that if we pet est dee work,the kids wield be so fmscieded wills thework that they would do II but Mi didsithents." Still mother swim equessedherself: "The ouly Wog that I disegreedwith was removing of the powerstructure at coca I thiak it should havebeen a gradual thing, because the chil.darn went from one edema to the otherovernight, and they really didn't Wowhow to cope with it."

COSAMIR

14041:Pupiter4

f4sli Ye".

/t

110 ionog dlopo so illoolaoistil illos *0ono ouraeon* Wow woe -101***" *oft *

moo soommiog *a 4014 NM *Who itoIliso* *MOP lailasago * on 1401 ton*

*1411 evow ollosooto 41**** UN& 400 SAONIONOWIL I orme *OM* nol1i

lit ihoop vassoontI Um** otliontoosA Itostor ongio 4046400 lope hot I. opo

yoostot stION* *op oodlooll to awl U. swam Oho

*NW looks" # #4d Now ok. No do, silk sloghood I* go ilenk *oodilional assodk* ihrn *

kw a *Me OlogOI rog honoinW hfir, taw, oiloits, 1Orr **oho i a mom Ile I* IOW lifluse *knot

oloOlessfy Sels work mounasonl Iloolook ono Oso

the Wis. boll *ode loon woo is Shoo* WOO isdor baby ono *Oh Oho hulk bydileg ü abogrolate and gmlog loork ev

Om doom Ao spool *wow pokey iro wow all*a Ms pawns fiffili OrIter Itellit

$1161. :you It an ordy be pat* ere II* MAN

id* poist,* Olow*or oathsiwoal

oupoluallenel kWMOM IMO

To satisfy the Womb of der usllogn, the stallthe namerunto., and ohm Board of Show isms volIlon, Antioch sat up its alferentlated oloilon*staff plan I. which oh* school's imamstaff of IS waders aod Uwe specialists lady Rewas replayed by 17 Imam 11 Asstieebtotem and 14 community intern& The Maniaim was to keep pommel costs conslant(as stipulated by the Board of Mallon) pie, parand to provide Wain* for student tooth. we weters and career opportmlities for pow The pi;people in the community while berm- their drIns the edultiotudent ratio, done

/ 9

4' irniit,p*, 4k* 4IIiiii*

* AIsepi p$1Nh.M I$P i l**Pi iusu

'is ims 1ut*p dhwsi $pp.

P** IJWiUI1$I IIMfl** ø ffiuiPØ

*,iii Ke*djwIP* jg

1$t.$$ *e$*

*$I 'Ih &i*iMI 1M444i., ffl$ 4 jw,* a $hH4*I

Ø$$$!p IL! JØIvftk .,

!t,miw uwiu i.m$ lMø;p*:* ___ '.

IlØI$, ;? Ot Mipsiit s. . -' 'W$ ØdI*

us II1* s$hM4 Thi* ,Ot

i_ , l!$ lhø*'441* *P Mu. 8$!U' 4MOI. M0$

wç, d$*s *$ha*. !h. upsc 'i4 iuuWus,,

4$Id$*k is! økøsft*9$lIMØ Ibii i4

MuW1Ø$ W

*ø ø#uij 4*j

$44* IliØ$ØØ *4*4* u* Ms$. Mj11I

Th P*L NM!*. M4*Ø$*ØM. *IØuI... ø4p

Sffl *4 14. -

*4i*uu iuw1 *i*:1* ói WfflJh PIwsi *.*im * uiurn fthik

rn*itru-rui

* 4E*: *hn1hwh 4- **W *h

t± ______* sd t$ s1i m*isHI IW*4 rn

* ssminsI' unui1 *4* *4**I M IP _ *4

kklIà

U

$MR4 *Ip ISI* .4àu--a N* $iP

1M pc* imil* *.$Ø* 1 diwø*ø

- _ .J1!iL SbC.7*4 lI*flWIilt IImI1I iwAi4 dim s'ui 4

jfl$ **øJ p pm4*i4 IiM4 *4

4MIN t;11MI $ M#*4- Mhi 4 4$Pb 1,-n

kstd W1Øp thw Mr LiSa4 __

18

netic atmosphere, unhappy teachers andparents, and a serious lack of suppliesand equipment and money to buy them(as the project director had already spenta large chunk of the year's budget). Nev-ertheless, under his direction, which wasdescribed by his staff as strong, support-ive, and cool-headed, the school beganto move towards a semblance of stabil-ity. When Mr. Lauter's dismissal broughta storm of protest from Antioch interns,Mr. Haskins was able to bring the youngpeople back to a united effort to helpchildren. He maintained an open doorpolicy; students were free to come intohis office any time they had a problem;be even had steps built that would en-able children to converse with adults onan equal level across a barrier that de-fined the office. And his emphasis wason community participation as quoted byTurner:

One of the most serious problems is whatappears to be the lack of involvement ofthe law community in the affairs of theschool and the lack of commitment ontheir part to the educational innovations.In my opinion it appears that a small num-ber of people decided what was goodfor the lawn. community. This is unsoundir one wants community involvement. Aprosram does not come from the brain ofone person or a few people, but from peo-ple interaellillg toward a goal. A programdoes not start full bloomas this one triedtobut develops piece by piece ...Mr. Haskins later observed, "The

greatest Input in the community couldhave been from the whites but most of

the middle-class white people have ei-ther been in and taken a large role, orthey've withdrawn completely."

Changes

The mobility and turnover of adults inthe learning centers arrangemeht seemeddisruptive to the younger children, andMr. Haskins converted the early gradesto self-contained classrooms. In the firstmonths the problems were very appar-ent, as noted in his interim report to theAntioch administration: "At this pointwe see a number of dangerous bugs inthe design of the teaching teams . . . ca-pable of undermining and perhaps de-stroying our main objectives. . . ." Themost serious of the problems were: notenough experienced personnel, difficultyin retaining teachers unless they weregiven coordinator or executive status,and the fact that the coordinating teach-ers were not capable of fulfilling theirdemanding roles. Mr. Haskins foresawfailure unless there were drastic changes,and getting more teachers skilled in non-traditional methods who could replacecollege interns took top priority. Often aclass was without a teacher, or with oneso ill equipped to deal with children thatshe was dependent 'upon the communityintern to establish some order. In hisplan to replace some of the Antioch in-terns, Mr. Haskins was supported by theschool board and ultimately the collegeas well. Although the change was not inAntioch's interest, to have opposed a

strong principal would have been to re-tard the movement toward local control.

Another Antioch role was that of con-sultant, and that seemed to clash withthe additional role of legal manager thatthe Board of Education had thrust uponit. These ambiguities, plus the enormoustime and energy that the project con-sumed, as well as an understood goal ofultimately transferring power to the com-munity as it was ready and able to ac-cept it, dictated a gradual change inAntioch's role from administrator toprofessional adviser. The first tangibleindication of the new direction camewhen a representative of the collegechose not to exercise his right to vote onthe school board.

As Antioch's hands-off policy becamemore evident, there were those who in-terpreted it as a desire to pull out of ashaky situation and avoid possible criti-cism for failure. Some welcomed the pos-sibility of greater autonomy. Some wereangered, some fearful that the schoolwould not be able to retain its communi-ty school status if Antioch pulled out.Some blamed Antioch for.all the school'sills; some talked of an all black school;and others sought dramatic confronta-tions with "downtown" (the D.C. Boardof Education). Still others, includingschool board chairman Bishop Reed andboard member Mary French, maintainedthat Antioch had been supportive.

With the shift in Antioch's role, therewas often confusion about who shoulddo what. According to Mr. Haskins:

19

"They (Antioch) just reduced services aspeople pulled out . . . I began to fill in."That meant choice of curriculum, in-structional policies, and fund raising.

Earlier in their capacity as fund rais-ers, Antioch representatives had appliedfor funds from the Ford Foundation. InJanuary 1968, midway into the project'sfirst year, Ford made it plain that moneymight be available, but only com-munity-controlled school. As sFordpressed for an answer as to the exact re-lationship between Morgan and AntioCh,the administration of the school lookedto the Board of Education to redefinelines of authority.

Evaluation

In March 1968, as the first year of theproject was nearing an end, the Board ofEducation completed its annual surveyof reading skills. Morgan was one ofonly six schools showing some improve-ment over the previous year, while thesystem generally showed decline. News-papers and magazines printed positiveand often glowing reports of Morgan asa sign of hope on the educational hori-zon.

However, an informal report by An-tioch cited the following weaknesses inthe project: a hasty beginning, a lack oforiented and qualified personnel, and toomany hmovations introduced in too shorta time. Poorly defined roles were seen asthe cause of sharp disagreement betweenteaching staff and school board members.

20

On the positive side, Antioch found that"children no longer show a once typicalwithdrawal and a combative self defensestance when approached by a principalor teacher. . . ." The report concluded:

The idea of community internship hasbeen conclusively shown to be viable, andthe great majority of the first participantshave been launched successfully on a ca-reer they otherwise lacked . . . The schoolcouncil has been, to the best of our knowl-edge, the most successful illustration todate within a large city that a Board ofEducation and a neighborhood council, theteachers union, and an institution ofhigher education can all work well withina critical and major delegation of authorityto the neighborhood.

Another report on the first year's opera-tion, prepared by the school for the com-munity, set forth the school's philos-ophy:

The school should take its character fromthe nature of the people living in the com-munity and from the children utilizing theschool rather than rigidly defining itself asan institution accepting only those peoplewho already fit into a set definition . . .

children should not be abused either phys-ically or emotionally,. . . the concept ofcompetition has no 'place in a communityschool . . . the school should be an educa-tional center for all.

Concerning curriculum content and se-quence, the Morgan report stated:

. . . these factors are relatively unimpor-tant, for if we can keep a child intenselyengaged in the process of learning for thesix years we have him in the elementaryschool, we would be willing to guarantee

that no matter what comes first or whetherthere are gaps in information, he will con-tinue to observe, explore, and question thethings around him to be successful . .. weutilize the same subject areas as all otherschools, namely: science, math, socialstudies, language arts, and the creative andmanual arts ... we allow our teachers to beextremely free in how this material is pre-sented. Our one rigidity was and will con-tinue to be . . . that subject material willnot be used to insult, belittle, or degradeour children or their families.

On definition of roles:The specific details of program and theirimplementation are --the responsibility ofthe staff with the Community SchoolBoard constantly evaluating results andapproaches ... The Board must control tothe maximum extent . . . staffing, curricu-lum financing, outside resources, and useof the physical plant.

By the spring of the first year it wasclear that Antioch's role as manager hadended, although the college would con-tinue to have interns in the school. Mor-gan had been tested and found to havemade academic gains, and communitypeople were feeling vindicated in theirfaith in community control. In April1968, the school board submitted a pro-posal to the Board of Education callingfor greater autonomy and provisions tomake the school an education-recreationcenter for the whole community. Dr.Hansen had been succeeded by Superin-tendent William R. Manning, who firstindicated he would deny the requestsand later said he would consider them ifthey were reduced. His reluctance.

21

stemmed from legal questions raised bythe request for autonomy, serious divi-sion in the community (some civic groupscomplained that their representativeswere excluded from the school board),and the school's decision against recom-mending continuation of its original re-lationship with Antioch. It was only aftera much publicized show of determina-tion, in which hundreds of communitypeople jammed meeting rooms to air theirdemands, that the autonomous featureswere granted. One meeting, attended by350 people, contrasted sharply with theusual monthly community meeting at-tendance of 20 or 30 people. Apparentlymany agree with one community leaderwho says he gets involved "when partic-ipation counts."

On September 19, 1968, the Board ofEducation released a policy statementgranting the school "maximum feasibleautonomy." This was to be implementedthrough a Division of Special Projectswhich aid the board in staffing, curricu-lum formation, and instruction. Theschool would receive the support andservices available to all other schools, aswell as funds for an evening school forchildren and adults. The local schoolboard would determine priorities for theexpenditure of funds.

CHAPTER IV

1/69--6/:

74 No$a0441 No/

22

Two milestones were marked simultane- tarously: the beginning of the second year su-of the project and new autonomy for the ca_

school. The Washington chapter of the boAmerican Federation of Teachers enthu-siastically endorsed the Board of Educa-tion's action in a position paper whichcalled for uniting teacher power andcommunity power to redefine the func- MItion of education, to make decisions in tipregard to procedures and process of edu- nircation, and to provide the community edwith, absolute administrative and fiscal inE

control. anThe Washington picture was quite dif- ch

ferent from that of New York City at s el

this time. There the teachers' union's op- Foposition to community control of schoolsled to three disastrous teachers' strikes. HE

In contrast with the theoretical position 1111

of the national American Federation of 191

Teachers in support of community grE

schools, the Washington local has in fact otfvigorously supported the autonomy of ea:the Morgan Community SchooL How- St:ever, the local has maintained a hands- choff attitude in relation to the develop- lec?

ment of the school itself, even though all inithe Morgan School teachers are union 19members. Though it would like to be- pricome involved, the local has never been co-

approached by the community for help. caWhether or not a satisfactory union and tincommunity school board "contract" will Faemerge remains to be seen. Se

Furthermore, in 1968, the district had ME

its first elected Board of Education in withis century, and Julius Hobson, the mili- isl-

22

Two milestones were marked simultane-ously: the beginning of the second yearof the project and new autonomy for theschool. The Washington chapter of theAmerican Federation of Teachers enthu-siastically endorsed the Board of Educa-tion's action in a position paper whichcalled for uniting teacher power andcommunity power to redefine the func-tion of education, to make decisions inregard to procedures and process of edu-cation, and to provide the communitywith, absolute administrative and fiscalcontrol.

The Washington picture was quite dif-ferent from that of New York City atthis time. There the teachers' union's op-position to community control of schoolsled to three disastrous teachers' strikes.In contrast with the theoretical positionof the national American Federation ofTeachers in support of communityschools, the Washington local has in factvigorously supported the autonomy ofthe Morgan Community School. How-ever, the local has maintained a hands-off attitude in relation to the develop-ment of the school itself, even though allthe Morgan School teachers are unionmembers. Though it would like to be-come involved, the local has never beenapproached by the community for help.Whether or not a satisfactory union andcommunity school board "contract" willemerge remains to be seen.

Furthermore, in 1968, the district hadits first elected Board of Education inthis century, and Julius Hobson, the mili-

tant black leader who had successfullysued the Board of Education, led all othercandidates in gaining election to the newb oard.

New Services and Follow Through

In the second year of the project, theMorgan School became a focal point forthe community with the addition of eve-ning adult education classes in drivereducation, community development, typ-ing, sewing, music, physical enrichment,and a health clinic for all neighborhoodchildren, ages one to 1B. In addition, thesecond year saw the introduction of theFollow Through Program.

Follow Through, an extension of theHead Start preschool program launchedunder the Economic Opportunity Act of1964, is essentially an educational pro-gram with added health, nutritional, andother services for poor children in theearly primary grades. Shortly after HeadStart was underway, it was noted thatchildren forgot much of what they hadlearned in that program when they wentinto traditional classrooms, and so in1967 Follow Through became part of theprogram in an effort to provide neededcontinuity. Under present Office of Edu-cation funding levels, the program con-tinues, at least through grade 3. WhenFollow Through started at Morgan inSeptember 1968, its director was a blackmale teacher, a former Antioch internwho had studied and observed the Brit-ish Infant Schools. Working with the

Education Development Center of Massa-chusetts, he modeled the ages 5-7 and6-8 groups on English informal educa-tion. The execution of Follow Throughservices, such as a free breakfast and hotlunch program, was handled largely byvolunteer community people. Upper-grade children were also given freemeals.

In Morgan, the youngest-level FollowThrough program aims at eliminating in-flexible predetermined curricula. Theprogram is child-centered rather thanteacher-centered. The general goals in-clude growth of reading skills, the de-velopment of self image, and encourage-ment of social skills. Additionally, prac-tical math, science experiences, and theability to communicate are stressed. Spe-cific minimum goals for the youngstercompleting two years of the program in-clude his being able to read and writehis name, to read and write the alphabet,to read and write symbols from one toten, to recognize and name colors, to rec-ognize some rhyming sounds, to havesome understanding of opposites, and tohave some sense of sequential develop-ment in a story. Children work in groupsto which they are assigned on the basisof emotional maturity. They are free tomove to other groups to be with adultsor children with whom they are morecomfortable or to engage in a differentactivity. The two-year program is meantto encourage respect for differences rath-er than encourage competition. It is seenas a means of providing opportunities

...

23

for children to learn from each other,which, it is believed, contribute to asense of growing up and of responsibilitytoward others.

Besides Follow Through, other addi-tions in the second year of the projectwere a storefront nature center and anarts workshop in the Morgan Schoolneighborhood. The nature center, locat-ed 'across the street from the school,evolved through the labors and help ofcommunity people and money from do-nations and foundations. Today, the cen-ter holds about 50 animals, includingrabbits, opossums, mice, chickens, ducks,and a goose. Neighborhood children carefor the animals; they feed them, buildand clean their, living areas; they observeand discuss them before, during, and af-ter school. They come in groups from theschool or individually. The center aver-ages 50 to 100 visitors a day. Older boysmany of them dropoutscongregatethere. Some teenagers develop interestsat the center that present possibilities forjob opportunities with the National ParkService and National Zoo. The directoris D. Malcom Leith, a young white, whomakes a small living from his efforts.

The Art Center, called New Thing, hasgrown from one to two arts workshopsand a central office. This unusual projecthas provided exciting opportunities forcreative children from the MorganSchool, as well as the entire community.In his description of New Thing, TopperCarew, the founder-director, wrote: "Mything is to make people aware of their

24

being, to make them aware of their dig-nity, to make them more conscious ofthemselves. And allow, or try to preservethe humanity that I think exists in ablack community." His aim was to in-volve many different age levels as a"built in reinforcement," because, in hiswords, "it's very important to develop asort of communal feeling around educa-tion."

Strengths and Weaknesses

By the second year it was generallyagreed that Morgan was a healthier andhappier place for children to go to school.There were additional services and cul-tural enrichment opportunities inside andout, and the school was extending itspositive influence into the community.Academic testing indicated that theschool had reached national norms in theearlier grades.

In January, 1969, an article in a QueensCollege newspaper (see Bibliography)stated, "Morgan contends and visitorsperceive that the children are happy, re-laxed, and interested in learning." Mr.Haskins was quoted: "Our kids are stillnot reading on grade level, but at leastthey're not afraid of reading." Alsonoted, however, were problem areas, in-cluding serious lack of money, adminis-trative help, and adequately preparedteachers. The paper then commented:

The major inhibition is financial. Morganhas been successful in attracting somefoundation and other support, but it still

must function on a shoestring budget.There is notably no extra money for ad-ministrative staff. Morgan has an electedboard that must make policy decisions andact to enhance the school program; theboard, however, has no staff but the princi-pal, for whom time spent for the board in-evitably means time away from the educa-tional program. Developing proposals foradditional funding, representing the much-discussed community school before thepress and in other public arenas, and avariety of other tasks all fall on the princi-pal ... There are no funds to support cru-cial staff development programs. Existingteacher preparation programs in Washing-ton produce almost no elementary schoolteachers really well grounded in mathe-matics or science, and not a great many insocial studies or language arts. Morgan'sprincipal contends that inadequately pre-pared teachers are a greater liability, fordisadvantaged children than for middleclass children, observing that a studentwhose father is a chemist or engineer maybe motivated toward science even withpoor science teaching in school, but thiswill not be the case for a student whosefather is at best marginally employe&

Another major problem was staff turn-over. Mr. Haskins found that many youngwhites were anxious to teach at Morgan,but he felt that "whites are unable tostand certain pain. . . . Lots of time andenergy was put into those who don'thave the stomach." Mr. Thomas Porter,director of the Antioch Washington pro-gram that supplied the interns, said thatMorgan was hurt as Antioch is hurt "bytoo much turnover in personnel whichdestroys continuity."

As the second school year ended, the

energetic but overworked.,principal an-nounced that he would take a one-yearleave of absence, but he later declaredthat he was leaving permanently to be-come a teaching fellow at Harvard Uni-versity. Also, during the summer, BishopReed died, leaving another serious voidin community leadership.

Influence on Other Schools

There is no doubt that"the much pub-licized events of the Morgan School hadtheir impact on the educational system.In 1969, a group of Washington highschool students received the D.C. Board'spermission to spend three hours a day ina freedom school where they wouldstudy black history, Swahili, and relatedsubjects for credit. The students chosetheir teachers who were paid by a non-profit organization called the EasternHigh School Freedom Corporation. In1969, the Takoma Elementary School innorthwest Washington was the settingfor a week of intensive community dis-cussion of plans for a new building. Inan atmosphere of self help and self de-termination, the discussions went farpast the proposed building into the areaof educational goals and community con-trol of the school. It was Morgan's ex-ample that led to the formation of thefederally financed Anacostia Projectadecentralized district covering 11 schoolsin the southeast section of the city.

In August 1969, Education Daily stat-ed, "Reacting to the demands of parents

25

of youngsters at the Adams ElementarySchool, the Washington, D.C. SchoolBoard has approved plans to begin thecity's second community control experi-ment. The board also asked administra-,tors of all the schools in the city to sub-mit long-range plans for neighborhoodcontrol." Another educational publica-tion, the NCSEA News, called the 1968-69 school year "the year of communityeducation and involvement."

In the summer of 1969, CongressmanJohn Dellenback headed a governmenttask force to investigate and report onexperimental projects in education. Hestated in a letter, "The trip to the Mor-gan Community School . . has solidlyreinforced our belief that the communityshould meaningfully participate inschool decisions." Another member ofthe task force, the school's principal, re-ported that a major problem was the per-sistent red tape involved in getting sup-plies from the central board. Althoughsupplies, like operating funds, wereeventually made available, without astock or contingency fund the school'soperation was sometimes hampered. Arepresentative of the central board re-ported that in trying to be responsive tothe school, the Board of Education some-times found itself at odds with the cityadministration. At that time, the oldthree-commissioner form of governmenthad been replaced by a mayor, but hestill had to go to conservative congres-sional committees to request funds forlocal use.

CHAPTER V

117O-71

Hi Sdoot

1:044-7

:-

Morgan is truly a community school. Ac- Board acording to Mario Fantini: Superin

Scott. (When r arents, students, and communities 1970 inparticipate in reform, we can assume that oarbd.)the chances for developing a climate ofhigh rather than low expectations will besignificantly increased ... We have known School Cfor some time now that major agents ofsocialization for the young child are bis On t:family, his peer group and his school. We white Iseem to know also that growth and devel-

;

opment are significantly affected, posi- tractiontively or negatively, depending on the dents arelationship that exists among these major childrersocializing agents. When there exist dis- Thereconnection and discontinuity between or whiteamong them, the child's potential can be

t

affected adversely. specialiafter re

The Ford Foundation backed up Mr. the teacFantini's confidence in the community union rschool concept by awarding a grant of der the$60,000 to the Morgan School in 1970. year p1The principal and school board allocatedhalf the money for board and staff de-

the hig:for cert

velopment, and the remainder to reno- dudevate the annex, to help provide bus trans- teacherportation, and to prepare a report to the ing specommunity a physi

In 1971, Reverend Walter Fauntroy be- teachercame the first elected District of Colum- Thebia Representative to the Congress. Al- a nong:though not a voting member of Congress, Eight ahe will have a voice and a vote on the geneouD.C. congressional committee. While this roomsrepresents progress, the local govern- internment still lumbers under an inadequate youngesystem. There are, however, changes on contairthe educational scene; both the leader- ouship and the majority serving on the

eatc lithl

3 /

26

Morgan is truly a community school. Ac-cording to Mario Fantini:

When parents, students, and communitiesparticipate in reform, we can assume thatthe chances for developing a climate ofhigh rather than low expectations will besignificantly increased ... We have knownfor some time now that major agents ofsocialization for the young child are hisfamily, his peer group and his schooL Weseem to know also that growth and devel-opment are significantly affected, posi-tively or negatively, depending on therelationship that exists among these majorsocializing agents. 'When there exist dis-connection and discontinuity between oramong them, the child's potential can beaffected adversely.

The Ford Foundation backed up Mr.Fantini's confidence in the communityschool concept by awarding a grant of$60,000 to the Morgan School in 1970.The principal and school board allocatedhalf the money for board and staff de-velopment, and the remainder to reno-vate the annex, to help provide bus trans-portation, and to prepare a report to thecommunity.

In 1971, Reverend Walter Fauntroy be-came the first elected District of Colum-bia Representative to the Congress. Al-though not a voting member of Congress,he will have a voice and a vote on theD.C. congressional committee. While thisrepresents progress, the local govern-ment still lumbers under an inadequatesystem. There are, however, changes onthe educational scene; both the leader-ship and the majority serving on the

Board of Education are black, as is theSuperintendent of Schools. Hugh J.Scott. (Julius Hobson was defeated in1970 in his bid for reelection to theboard.)

School Organization

On the 750 children enrolled. 14 arewhite; two are of Spanish-American ex-traction; the rest are black. Most stu-dents are poor, and almost half of thechildren are not living with both parents.There are 21 black teachers and sixwhite teachers, including a curriculumspecialist who came from Minneapolisafter reading about the school. Most ofthe teachers are experienced, and all areunion members authorized to teach un-der the D.C. Board of Education's two-year probationary contract (and underthe higher of the board's two categoriesfor certification). Other full-time staff in-clude five Antioch graduate studentteachers, 30 community interns, a read-ing specialist, a librarian, an art teacher,a physical education teacher, and a danceteacher.

The school still operates according toa nongraded cooperative teacher format.Eight adults work with about 100 hetero-geneously grouped children, using fourrooms (25 children per teacher with anintern assigned to each room). In theyounger teams, classrooms are now self-contained, with the same staff, through-out the day. In the older teams, eachteacher selects one area of specializa-

3 /

lion, depending on her own spedal tal-ent or interest, and then operates a learn-ing center in that subject. In .both thelearning centers for older children andthe self-contained classrooms for young-er children, students work in loosegroups or dusters on different activitiesor various phases of a subject. This in-formal organization is modelled on theBritish Infant School.

One teacher on each team is a coordi-nator for the larger group. At team staffmeetings after school hours, the coordi-nator works with other adults on curricu-lum, activities, and individual problems.Except for general aims and goals andcourse planning, which emanate fromthe principal for older students and fromthe principal and Follow Through direc-tor for younger students, the teachersfunction as more or less independentagents.

Administration

Since September 1969, the project hasbeen guided by its second principal, Mr.John Anthony. A graduate of Payne Col-lege, Mr. Anthony was a leader in a Flo-rida school strike and worked briefly asa counselor in the Morgan School beforemoving up to principal. He came to Mor-gan out of a desire to work in an inter-racial school. All administrative person-nel, including three secretaries, are black:the principal, the Follow Through direc-tor, a community organizer, a counselor,and an assistant principal who presides

3

27

over the annex four blocks away. Al-though the prindpal is the educationallinden In a community school like Mor-gan the highest authority on policy restswith the school board.

The Morgan School Board of 15 mem-bers is elected by the entire community.The board's membership inaudes sevenparents, three other community resi-dents, three persons between the ages of16 and 23, one professional member ofthe school's staff, and one paraprofes-sional. Mrs. Mary French, who contrib-uted years of active participation and anenormous amount of time and energy toschool affairs, is the current chairman.

Eady ChildhOOd PfOgratill

Of the seven teams that make up theentire school, three teams are part of theFollow Through program. Teams one andtwo include children from five to sevenyears old; team three, six- to eight-year-olds.

A typical day might begin with young-sters, sitting on the floor around theteacher, talking about the weather. Afew may be disengaged on the fringe,using blocks or exploratory learning ma-terials or looking at a book from the li-brary corneror just gazing into space.Although the teacher tries to involvethese children to a greater or lesser de-gree, these fringe activities are accepted,even during a more formal lesson.

The formal lesson begins with direct-ed instructions, and then small groups

28

of students work independently or withan intern. The teacher may work with agroup, or she may work with individualstudents, each on his own level. Thegroups or "clusters" might be workingin different areas of a given subject, suchas reading. One teacher, employing theS.R.A. Reading Kit, Reader's Digest SkillBuilder, and other resources, sets up sixgroups who work for improvement in in-dependent reading, comprehension, syl-labication, use of dictionary, etc. Againthere may be fringe activity, sometimesnegative and distracting, but often posi-tive and constructive (for instance, chil-dren reading alone or an older child read-ing to a younger child). A recent visitorsaw a youngster rise suddenly from hisseat, pick up a large piece of wood froma nature exhibit, and lift it high over hishead several times. Since the teacher inthe room was neither threatened nor an-noyed by the movement, the incident wasover when the boy replaced the objectand returned to his seat. The school'soriginal proposal to the Board of Educa-tion in 1968, had stated, "with new edu-cational methods and a flexible approachit should be possible to narrow sharplythe definition of seriously disturbed chil-dren who would need a program di-vorced from the total school curriculum."

After the formal lesson, there is dis-tribution of milk (supplied by the school)and cookies (when the teacher buysthem). A recess follows, and children goto a public playground which is wellequipped, or to the school yard which

has little except swings and space tomove around, concrete, and the grimwalls of abandoned buildings. The onlycolor in the schoolyard is supplied by bitsof paper and soda cans. In bad weatherchildren play indoor games such as pitch-ing horse shoes. With only one large areawhich serves as auditorium, lunchroom,and gym, a hall or washroom may be uti-lized for either learning or recreation.

The morning continues with storyreading and telling and conversation,and then lunch. Most of the students ben-efit from the free breakfast and lunchprogram which provides well-preparedfood that the children seem to like.Equipment to flash-heat individual mealsin aluminum foil dishes is a recent ac-quisition, and with two full-time lunchclerks and volunteer parents, the mealsare quickly distributed.

Midday, the auditorium is the hub forchildren, staff, and administrators. Get-ting ready for lunch requires all avail-able hands, often including the principal,to help custodians quickly clear awaychairs and equipment and set up largefolding tables with attached benches.Sometimes the princiyal stations himselfat the door to see that everyone gets hislunch. The young children eat in theirrooms. Lunch is a noisy, social affair foradults and childrenwithout traditionalmonitors but under a few alert adults.

Lunch is followed by a free period inor out of the building. A favorite pastimefor some children seems to be climbingthrough the low windows between the

3 3

auditorium and the schoolyard, an activ-ity which usually brings a loud repri-mand from the adult. Theoretically, arest follows lunch, but teachers tend tocut it shorter and shorter because of itsunpopularity.

The remainder of the day is devotedto the children's free use of exploratorymaterials and (time and temper permit-ting) a science or social studies lesson.Says John Anthony, "I believe in kidshaving their freedom: I believe that kidslearn when they are happy, but . . . latein the day we are not so sure that kidsare involved in a learning activity."

Physical Plant

For lack of space in the school, theoldest teams are housed in the annexwhich has separate lunch facilities. Thissmaller structure, built for industrial use,is high above ground and reached bysteep concrete steps. Money from theFord Foundation financed the filling andleveling of the adjacent slope for a playyard. Both the main building and the an-nex are about 80 years old with neglect-ed exteriors and dusty or muddy areaswhere grass should be.

The outside of the main building givesno hint of the good things that are goingon inside. The rooms are large and bright(custodians painted them on their owntime). The classroom floors are carpeted,and children like to sit on the floor toread or play. Some rooms are clutteredand littered; others are not, but none

29

could be described as sterile or imper-sonal. Inside the annex there are new toi-let rooms and an indoor area far gamespaid for by the Ford grant. The class-rooms are large and bright, but the ad-ministrative office is a narrow rectangu-lar space with a door at one end and awindow at the other. One very hot dayin June, Mrs. Arlene Young, assistantprincipal, talked about the school in heroffice as her secretary, Mrs. John An-thony, hemmed a child's dress. She ex-plained,

. . . They come for so many little things:we're buying graduation dresses for thechildren, shoes, things they need andknow they can't get.

Upper School Program

The organization of the upper schoolis both departmentalized and heteroge-neous, with the same team and staff dif-ferentiation as in the lower school, butwith a somewhat more structured pro-gram. Students move for their lessons be-tween various rooms which are designat-ed Reading Center, Math Center, SocialStudies Center, and Science Center.Within these centers students work inclusters geared toward strengthening amajor subject. Students have individualfolders of completed work which theteacher evaluates with the child. Theseevaluations are designed to determinewhen a skill will be retaught, and when achild will proceed to the next skill.

30

One teacher who consistently sparksexcitement is Mohammed El-Helu, ayoung African who has been teachingscience for three years. His use of dem-onstrations and experiments makes hima popular resource person. It was point-ed out that prior to the time the schoolwas able to hire its own staff, it had ahard time getting Mr. El-Helu who couldnot be certified because he was not a cit-izen. After much negotiating, the Boardof Education waived its citizenship re-quirement, and he was hired. Since thenseveral African teachers have joined thestaff.

The Human Development Program cur-riculum aims to give a student opportuni-ties to discover information about him-self, his group, and his environment, andto respond to his discoveries. Units dealwith the student in his community andWashington, D.C., as well as with Afri-can, Japanese, and Southeast Asian cul-tures. Activities call for trips to investi-gate different income levels in housingand visits to embassies, the zoo, and theMuseum of Natural History. In spite ofsome interesting trips, the opportunitiesfor using Washington as a resource havenot been fully developed. One majordrawback has been the lack of trans-portation.

Both administrative and board leader-ship agree that the school needs to buildcurricula to interest children. The assist-ant principal, Mrs. Young, explained,"We have been drawing from the regularD.C. program curriculum guide; we pull

out things that we think relevant to ourchildren, then we add current events . . .

things that are happening in this commu-nity, social studies. . . . We try to find asmany new textbooks as we can." In spiteof Mr. El-Helu, the Human DevelopmentProgram, and other highlights, however,the curriculum appears to be generallyunimaginative.

Nonacademic Program

The extended day program begins af-ter school and continues until 9 P.M.; itserves more than 300 local children andadults, as well-as Morgan students andparents. There is dancing, gymnastics,karate, basketball, baseball, cooking, andsewing. For adults there are also highschool equivalency, typing, and driver'seducation classes. Apart from the lack offacilities, the physical education programleaves much to be desired; a typicalscene was that of children lined up topractice head rolls. An art program forstudents conducted by a very creativeteacher appears to be too ambitious forone individual to implement, and it oftenfalls back on conventional projects. Al-though there is no formal arrangementwith the New Thing arts workshop, chil-dren who show special interest or talentcan go there on their own and find op-portunities for growth.

After-school socials are popular anddominated by the sounds of rock music.Even during school hours, the rock andbongo beat wafts through open windows

into the street. A visitor watched a teamin the lower school dress up-iir dashikis,sarongs, and geles (African headdress)made by their teachers; the children werepreparing for a dance program at FederalCity College that drew a full house. Atone Assembly, children did contempo-rary dances against a background of aflashing psychedelic light show riggedup by an intern. A large group of boysand girls performed on bongos while theteacher called out to the whole schoolaudience and was answered in soundsderived from African dialects. Everyoneparticipated in this activity. The assem-bly closed with an award program de-vised by one of the teachers.

Board and Staff Training

Training for people working in theschool is and has been a top priorityneed. Both Mrs. French and Mr. Anthonywere dissatisfied with some of the teach-ers' interpretation of the British InfantSchool methods. From observation andtalks with Mr. Norman Precious, head-master of the Leicester School in Eng-land, Mr. Anthony decided that some-thing had been lost in translation from arural English school to an American ghet-to school. Accordingly, the principal ar-ranged (with the help of a Ford grant)for Mr. Precious to hold a two-week sem-inar at the school during the summer of1970.

TMs seminar included several eveningsessions for purposes of interpreting the

31

Infant School philosophy to the commu-nity. The daytime program consisted ofmorning lectures and discussions forteachers, followed by afternoon work-shops and demonstrations. Teachers whoattended were paid for their participa-tion. (Community interns are paid on ayearly basis.) There was a disappointingattendance of 20 people, mostly commu-nity interns; Mr. Anthony explained thatthe Ford money had arrived too late topay more teachers.

In his talks, Mr. Precious pointed outthat the process of informal education isvery gradual, in which there are stepsthat may appear very traditional yet arenot, if only because of the teacher's atti-tude. He maintained that personal com-mitment and continuity are essential ifpeople are to implement such a program;obstacles and setbacks must be acceptedwithout abandoning the program con-cepts.

Mr. Precious stated that teachers can-not give students the benefits of experi-ence and knowledge without giving themproper guidelines, modeling behavior pat-terns and standards, and making clearthe discipline involved in work. Theseaspects of learning should be interpretedin an individual way, with each childhelping to formulate the rules and under-standing the reasons for them. rWe can-not expect children -to come into thisworld and develop their own-rules:andstandards." He maintained also that achild must not be allowed to remain un-involved.

32

At the final session, he discussed theteacher's aims:

She will be concerned about each child'sintellectual development and will be think-ing of ways to stimulate further activitiesthrough the introduction of new materials. .. at the same time being aware of eachchild's personal qualities and having con-cern for the harmony of the class as awhole .. . Communication will play a veryimportant part in a child's learning, andtherefore every facility and opportunitymust be given for creativity, spontaneousdrama, reading, writing, and speaking . . .

The ideal schools, according to Mr.Precious, are those

. . . in which each child, in his own way,can satisfy his curiosity, develop abilitiesand talents, and pursue his interests, andfrom the adults and children around himget a glimpse of the great variety and rich-ness of life ...

He concluded:

Morgan typifies in its aims my feelingsabout myself as an educator. We must pre-pare its future citizens to be active, inter-ested participants in the affairs of thismodern complex society, to be responsibleand useful individuals, and to lead full,happy, and satisfying lives.

A community intern, who was activein school affairs, talked about her partici-pation in the seminar. "I really got some-thing out of this workshop . . . One thingI found out we did wrong, we put out toomany things at one time . . . we put outeverything and after two or three weeks'they (students) get used to it; nothing ex-cites them anymore." She said she learned

how to plan from day to clay, and to bealways alert for clues from the childrenthat would help her in planning and al-loting time for projects. She said shewould no longer try to keep everythingin her head, but take notes, and passfrom group to group to be sure each childgot the help, encouragement, and direc-tion he needed.

Regular staff development for the low-er school [Follow Through) is the task ofthe Education Development Center ofMassachusetts which works with teach-ers in implementation of the British In-fant School model. E.D.C. helped teach-ers and interns in practical ways, such asorganizing classroom space, buildingcardboard constructions which serve asgroup partitions, and furnishing equip-ment shelves. However, its importanttraining and research role during the cur-rent year has been uneven and some-times slipshod.

Staff development for the upper schoolwas sought through the Institute forServices to Education in Washington.The Institute usually works with collegestraining teachers, but was interested inworking with the whole staff of the up-per school in its normal setting at Mor-gan. The Institute aimed to establish anofficial statement of policy and to im-prove internal functioning and externalcommunication (in particular, communi-cation from staff to board as to why theschool is organized as it is and how basicskills are to be accomplished, and fromboard to staff on perceptions of the com-

munity). Of special concern to Mr. An-thony as well as the Institute is under-standing the questions posed by parents:What are the goals and objectives? Howare they reached and evaluated? How doyou feed back into practice what comesout of the evaluation?

The Institute was scheduled to beginin September 1970, but necessary fundsfrom Ford were not yet available. Fordwas waiting to see how an earlier checkfor bus transportation was-spent, and thebus problem was not resolved for lackof legal aid. This kind of circular red tapeis not uncommon in Morgan, which de-pends on grant money to implement itsprograms.

Finances

The school currently operates on apolicy of Agreement with the Board ofEducation, effective 1969 through 1972.This document very nearly duplicatesthat of 1968 which gives the communityschool board autonomy in staff determi-nation, curriculum formation, and in-struction. Like the first agreement it pro-vides funds for an evening school andgives the local board power to determinepriorities for the expenditure of the nor-mal allocation of funds. But what was amajor victory in 1968 represents no prog-ress in 1971. Mr. Anthony points out thatrequests must be made to the centralboard for each budgetary item. He addsthat he gets the money, but he has towait for it, and without a contingency

33

fund, this sometimes presents problems.He says, "You really don't have commu-nity control . . You never will have ituntil you control the purse strings."

The Policy of Agreement also statesthat the school may receive all federal orprivate funds directly. Since the schoolhas no personnel for this function, thevolunteer school board makes contacts,writes letters, and holds interviews forfunding, staffing, and public relations.Mrs. Mary French, school board chair-man, who sometimes represents theschool at meetings and conventions,gives the school an inordinate amount ofher time, as do the other dedicated boardmembers. The principal must work close-ly with community people and often pro-vide the expertise for board matters. Hemust also be available to prospectivedonors who want to talk to the head man.Because he knows the need, Mr. An-thony manages to be involved in manytasks not normally associated with theposition of Principal. One Christmas, forinstance, he spent most of the holidayworking with a paid contractor convert-ing a section of the hall into a musicroom.

The Spring Crisis

In Morgan, crisis situations are almostroutine. In the spring of 1970, about twoweeks after a school board election thatput Mrs. French into the chairmanship,The Washington Star (June 4, 1970) re-ported:

34

. . at least fifteen of the school's twenty-seven teachers have decided not to returnfor the next school year. Some are leavingfor personal or family reasons, but mostare resigning because they are at odds withthe leadership voted into power . . . "Thepeople elected represent a trend back torepressive education, to law and order,"said Mrs. Jeanne Walton, a Morgan Schoolboard member who was not up for re-elec-tion. She had led a minority faction thathas been critical of Mrs. French and theschool's principal, John Anthony. (Mrs.Walton once taught at Morgan and is nowa field representative for the WashingtonTeachers' Union.)

In addition, the only white parent boardmember resigned and took her childrenout of the school.

Mr. William Simons, president of theteachers union local in Washington, feltthat the dissatisfaction was largely dueto a lack of effective leadership since thedeath of Bishop Reed and the change ofprincipals. He said, "One of the thingsabout the experimental projects is thatit's difficult to spread these projects be-cause you don't have the same kind ofpersonnel to make them work in everysituation." Although relations betweenthe school and the union remain cordialand functional, they are not, he says,"what they once were."

Mr. Thomas Porter, director of theAntioch-Putney Graduate School pro-gram which until this year maintainedabout 30 graduate students working andstudying in Morgan, was interviewed atthe time the teachers said they wereleaving. His estimate of Mr. Haskins'

principalship was that sometimes the af-fective areas of learning were stressedto the detriment of some cognitive areas:"The school was full of love, but lovedoes not replace learning ... it facilitatesit but . . . does not replace it." He wasclose to Mr. Haskins, who, he felt, setthe prevailing tone that has resulted inhappier students.

Mrs. French says her total involve-ment in local education stems from herconcern about her daughter's education.Because Mrs. French is a lifetime mem-ber of the community and its elected rep-resentative, it is to her that many articu-late parents present such demands as:children should call teachers by theirlast name, bring home books, play less,and learn more. At the time of her elec-tion, Mrs. French answered her critics:"I represent the community, and I knowwhat people want."

Mr. Haskins, who was also completelyinvolved with the community, differed inhis ideas about children's needs, but hisallegiance to community control was notaffected by these differences. He felt thatthe interests of children and parentswere best served by community controlof the schools.

Most of those who were critical of thenew board were teachers on the FollowThrough teams. The director, Mr. johnCawthorn, who was leaving too, said,"Things got messed up in the last yearwith more formal niceties than freedom:more emphasis on children staying inclass, like that's the only place to learn.

. . That's where we made our mistake,there's been no rest since August 1968.We needed time to recharge;-being tiredmakes the other things more difficult."

Though the newspapers reported inJune 1970 that 15 teachers were leavingbecause they disagreed with the newboard, there were actually only nine of-ficial resignations and some of thesewere for other reasons. A couple ofteachers told the principal privately thatthey had been misguided or mistaken. Asa result of the publicity there was morethan the usual number of letters of ap-plication to fill teaching slots. Therewere also offers of help and money. Mrs.Anita F. Allen, president of the Board ofEducation, wrote in a letter, "If I can beof any assistance to you in your effortsto improve education .. . in our city, feelfree to call me."

With the confusion about how manywere actually leaving, it was difficult toplan for the new school year, but therewas no real anxiety about filling the po-sitions. Mr. Anthony and Mrs. Frenchtalked about hiring new teachers; theywould look for certified, well-qualifiedteachers, and then try to give them a re-alistic appraisal of the demanding workload of a community school.

Though the publicity may not havebeen harmful in this case, Mr. Anthonyand Mrs. French were not happy aboutit. Mrs. French said, "Those who madepublic statements only hurt children;they could have stayed, tried to work outdifferences, compromise." Mr. Anthony

540

35