Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]

-

Upload

brendan-mcsweeney -

Category

Technology

-

view

600 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]

![Page 1: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

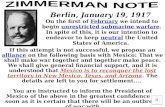

AN OVERVIEW OF CONFLICTS BETWEEN “NEO-LIBERAL” IDEOLOGY AND FUNCTIONAL MARKETS Kenneth R. Zimmerman, Ph.D.

SASE 2009Sciences PoParis, FranceJuly 16-18, 2009

![Page 2: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

2

Guesnerie identifies a market as a co-ordination device in which: the agents pursue their own interests and to this end

perform economic calculations which can be seen as an operation of optimization and/or maximization;

the agents' generally have divergent interests, which leads them to engage in

transactions which resolve the conflict by defining a price.

“… a market opposes buyers and sellers, and the prices which resolve this conflict are the input but also, in a sense, the outcome of the agents' economic calculation" (1996, p.18).

A market requires calculative actors to function and these actors require a market. These actors are both human and nonhuman.

Along with humans these actors include ideas and ideologies, as well as texts, tools, formulae, physical devices, physical structures, etc.

![Page 3: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

3

In order to conclude the transaction by agreeing on a price and enter and depart as strangers actors in a market must at least be able to, says Callon, establish a list of the possible states of the world; rank these states of the world (which gives a

content and an object to the agent's preferences); identify and describe the actions which allow for

the production of each of the possible states of the world.

Thus, if market coordination is to succeed, agents must not only calculate but also must have information on all the possible states of the world, on the nature of the actions which can be undertaken and on the consequences of these different actions, once they have been undertaken.

![Page 4: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

4

Market coordination encounters problems when uncertainties on the states of the world, on the nature of the actions which can be undertaken and on the expected consequences of these actions, increase.

Problems are at their worst when the uncertainties leave room only for pure and simple ignorance. Such situations are the rule and not the exception.

This is even more obvious with the uncertainties generated by technoscience.

![Page 5: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

5

Market operations and coordination also become problematic when the commodities for which a price is sought are uncertain, or randomly change in form or scope.

Similarly, problems occur when involved actors cannot be easily identified and communications between actors is unclear or overly complex.

Finally, market problems occur when a market, any market, is portrayed as superior to other sociotechnical agencements operating on other fundamental premises and with difference tools, texts, physical objects, ideologies, etc. that co-exist with markets.

In this vein of superiority markets are often identified as the “perfect” set of arrangements that cannot fail. They correct their own errors, and provide a level and type of information and organization unattainable from any other source. This picture of markets is just wrong.

The general question is thus the following: how can agents calculate when no stable information on the future exists?

![Page 6: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

6

My contentions are: neo-liberal economics at least impedes functional markets; often destroys functioning markets; no successful market can be constructed based on neo-liberal economics. The evidence for these statements is presented below.

![Page 7: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

7

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

Number 1 Calculative action is difficult to create and not the norm at all. Non-

calculative action is the more prevalent and usual. This means the creation and continuation of markets is difficult.

As a result the fundamental premise of neo-liberal economics and economies is tenuous, at best. Neo-liberalism’s fundamental premise is that all else must be subservient to absolutely free and unfettered markets.

Callon asserts that markets are able to survive due to framing. Markets survive not as a result of adding connections (contracts, rules, trust, culture) to explain and guide market actions, but rather by removing (bracketing) connections so that all that is left is a buyer, a seller, and an easily identified commodity. Only this framing allows calculation and the coordinated calculative actions of a market to take place.

But framing is difficult, incomplete, temporary, and always under threat from the wider actor-networks. In other words there is always a danger of the aspects of the calculation becoming entangled and thus losing the clarity and predictability achieved via framing.

It is here we see the first conflict between neo-liberal economics and functional markets. Framing is inconsistent with neo-liberalism’s central premise. All markets require detailed and continuous work (framing) from all the actors involved with the construction of a market (both those outside and those inside the market) to maintain the conditions necessary for calculative action. Absolutely free and unfettered markets to which all other actions are subservient are a practical contradiction. If this is the goal to which neo-liberal economics and economists are committed, above all, then no market can or will ever exist, and certainly no functional market can or will ever exist.

![Page 8: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

8

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

Number 2 A danger constantly facing market participants is that market

actions will change from calculative to non-calculative. Market “monitoring” and “regulation” by actors outside the

market can protect markets and market participants from this loss of calculative action. Once such a change is noted these market monitors can develop and implement changes to the market rules and participants to reverse the change and return calculative action to the market.

But such necessary corrections of markets are not possible so long as neo-liberal economic guidelines are dominant. These guidelines assert that markets need no regulation or outside monitoring because they are self correcting. In fact these guidelines assert that “correct” market actions are actually harmed by such regulation and monitoring.

Markets in actual economies around the world, even in the US, and those based on neo-liberal principles seem to contradict these guidelines and demonstrate the need for market monitoring and regulation. In fact, these actual markets clearly show that markets can remain markets only when such monitoring and regulation is detailed, strong, and constant.

![Page 9: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

9

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

NUMBER 3 Market monitoring and regulation also is essential for

another reason. Markets as networks for calculative action provide no device for assessing how they affect and are affected by other agencements. This is particularly the case in markets constructed based on neo-liberal principles. Obviously markets are not disconnected from other agencements.

This is certainly the case with the current world economic crisis, in which negotiations in financial markets, some thousands of miles away, has stressed actors from small businesses to national governments.

Even if neo-liberalism’s contention that financial markets correct themselves is partially correct, the real questions are how long will such corrections take and how much collateral damage will be done prior to the self correction? If the financial markets do not self-correct, the questions are what corrections are needed and how are they to be carried out? Marketing monitoring and regulation is the only viable answer to both sets of questions.

![Page 10: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

10

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

NUMBER 4 Market framing is always in a contest for survival, not only with

unanticipated events and actors, the limitations of the framing itself, but also with other agencements. In addition to the framing for the calculative action needed for markets, framing also occurs for the forms of action necessary for political, religious, technological, scientific, and other agencements. These criss cross and compete with one another for building materials and converts. The winners in these rivalries cannot be predicted.

Neo-liberal notions of a market create disadvantages for all efforts to organize markets.

First, neo-liberalism approaches markets as natural events, formed without substantial work or framing, and with little need for political actions to overcome rivals.

Second, neo-liberalism assumes that in all situations markets are at the apex of the relationships between actors. That is, when left unfettered and unregulated, actors will naturally create and interact in a market fashion and markets will always dominate other types of interaction. Such is not the case, however. As demonstrated by autocratic governments throughout history, markets are easily overcome and even perverted to serve political ends that are not calculative. An example today is China. China has created so called “market communism” as a means to further the world influence of China and prevent a democratic form of government being developed.

![Page 11: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

11

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

NUMBER 5 Because of the extreme difficulty of framing and the strong

likelihood that it is incomplete and temporary, and will eventually fail, market construction is itself necessarily incomplete, temporary, and fragile. What does neo-liberalism say about patching markets, or revising them for changed times, or totally rebuilding a market(s) when it fails?

Very little. For neo-liberals markets are natural, they just occur, and

their form and operations are solely dictated by the actors involved and the transactions between them.

And indeed this may actually be successful, for a time. But if the actors do not change and the transactions between them do not change, but still the market is failing, creating large opposition to it, or is creating results never intended by the actors and transactions, what is to be done? Working on these questions requires the kind of fundamental re-design and re-authorization of a market that neo-liberalism is simply incapable of offering.

![Page 12: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

12

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

NUMBER 6 In the context of the current crisis in financial markets many

scholars and journalists have specifically pointed to neo-liberalism’s antagonistic position toward retaining properly designed and functional markets as a primary cause. Of particular note is that these scholars and journalists “pull few punches” in the placement of most of the blame for the current crisis on this lack of concern and action by neo-liberalism.

Writing in the New York Times, Paul Krugman states,

But the wizards were frauds, whether they knew it or not, and their magic turned out to be no more than a collection of cheap stage tricks. Above all, the key promise of securitization — that it would make the financial system more robust by spreading risk more widely — turned out to be a lie. Banks used securitization to increase their risk, not reduce it, and in the process they made the economy more, not less, vulnerable to financial disruption. Sooner or later, things were bound to go wrong, and eventually they did. Bear Stearns failed; Lehman failed; but most of all, securitization failed. (March 27, 2009)

![Page 13: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/13.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

13

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

Harold Meyerson writes in the Washington Post that,So what kind of capitalism shall we craft? Now that the market

fundamentalism to which we've adhered for the past 30 years has -- by its own criterion of increasing shareholder value -- totally failed? Now that Alan Greenspan has proclaimed himself "shocked" that "the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders' equity" proved to be an illusion? But no one is suggesting an entirely new system. What we need -- and what we can build -- is a capitalism more attuned to our national concerns. The Reagan-Thatcher model, which favored finance over domestic manufacturing, has collapsed.

Manufacturing has become too global to permit the United States to revert to the level of manufacturing it had in the good old days of Keynes and Ike, but it would be a positive development if we had a capitalism that once again focused on making things rather than deals. [Up to a point German economic arrangements could be a model for the US.] The focus on long-term performance over short-term gain is reinforced by Germany's stakeholder, rather than shareholder, model of capitalism: Worker representatives sit on boards of directors, unionization remains high, income distribution is more equitable, social benefits are generous.

Making such changes here would require laws easing unionization (such as the Employee Free Choice Act, which was introduced this week in Congress) and policies that professionalize jobs in child care, elder care and private security. To be sure, this form of capitalism requires a larger public sector than we have had in recent years. But investing in more highly trained and paid teachers, nurses and child-care workers is more likely to produce sustained prosperity than investing in the asset bubbles to which Wall Street was so fatally attracted. (March 12, 2009)

![Page 14: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/14.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

14

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

A recent paper from the Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration, entitled The Financial Crisis and the Systemic Failure of Academic Economics places the blame for the financial market crisis squarely at the feet of academic economics. And since neo-liberalism has dominated academic economics for the last 40 years, the paper is placing the blame on neo-liberal economics. The abstract for that paper makes its case in the following way,

The economics profession appears to have been unaware of the long build-up to the current worldwide financial crisis and to have significantly underestimated its dimensions once it started to unfold. In our view, this lack of understanding is due to a misallocation of research efforts in economics. We trace the deeper roots of this failure to the profession’s focus on models that, by design, disregard key elements driving outcomes in real-world markets. The economics profession has failed in communicating the limitations, weaknesses, and even dangers of its preferred models to the public. This state of affairs makes clear the need for a major reorientation of focus in the research economists undertake, as well as for the establishment of an ethical code that would ask economists to understand and communicate the limitations and potential misuses of their models. (Colander, p. 1) (emphasis added)

![Page 15: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/15.jpg)

July

17

, 20

09

15

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris

CONCLUSIONS In testimony before a US Senate subcommittee in March of this year

Dr. Robert McCullough suggested that regulators of energy commodities markets would do well to take a page from An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in which 18th century economist Adam Smith writes of "the invisible hand" as a beneficial consequence of free markets. According to Dr. McCullough “It's been often quoted; it's been seldom read. The passage was not simply praise of the market. It was a warning against market participants who say that they are performing their trades for the public good. The point is, without understanding the market, without the data to review the market, we don't know that they're telling the truth or not.”

But collecting the data on positions and inventories won't be enough if it's not in the hands of the appropriate regulator, McCullough continued.

McCullough has, and not even between the lines, summed up why neo-liberal economics is bad for markets, many of the actors who participate in them, and the prices that are negotiated in markets. Neo-liberal economics is fundamentally the pursuit of two goals. The first is to convince everyone possible to reach that Dr. McCullough is incorrect. The second is that capitalism (understood as the preeminence of markets) is the absolute best economic system for the world but is under attack and must be defended. Neither of these goals serve the ends of better markets.

![Page 16: Zimmerman an overview of conflicts between neoliberal economics and functional markets[1]](https://reader033.fdocuments.in/reader033/viewer/2022051816/546211f3af7959477b8b4d5b/html5/thumbnails/16.jpg)

CONCLUSIONS Markets can be constructed and operate locally through

private actors and agreements alone. But markets can also be constructed based on central government facilitation and planning. And there are many other potential trajectories for market construction and operation.

Central planning and markets are not therefore necessarily at odds. Often they can work together. And every such possibility can in one fashion or another be understood in terms of spontaneous order, so long as we do not, as Hayek did a prior exclude certain actors (e.g., central government) from this creation process and recognize that spontaneous order is difficult to obtain, requires a great deal of work, and is always fragile and subject to failure.

Each market’s construction trajectory and rules should to be considered separately as a unique pragmatic process. Markets can happen and play out their life in many ways. The neo-liberal “one-dimensional” market harms both the operation of the markets and the welfare of those who depend on them.

July

17

, 20

09

16

SA

SE 2

00

9 P

aris