`You can't considerrassegna.be.unipi.it/20180509/OPC3003.pdfDubbed "Modicare" by local media, the...

Transcript of `You can't considerrassegna.be.unipi.it/20180509/OPC3003.pdfDubbed "Modicare" by local media, the...

Indians that could becovered by the new health

protection scheme

t dusk in front of BenaresHindu University's medicalcollege hospital, Ram Ash-ish Rajbhar, a clay labourerfrom a village 200km away,

settles on to a mat on the pavement,where lie will spend the night with his12-year-old, cancer-stricken son,Karan.

The hard ground - shared with scoresof other ailing Indians from far-flungplaces - has grown familiar to the fatherand son since the boy was diagnosed ayear ago. His treatment requires chemo-therapy every 21 days; a doctor sees himsome clays later.

But beds in the overcrowded publichospital are in short supply; patients aredischarged as quickly as possible, leav-ing the duo to camp on the pavementwhile awaiting a follow-up doctor's visit.The four-hour train ride home, thenback a few clays later, is too arduous.

That is not the only hardship. Whilethe government medical college ostensi-bly provides free care, patients must payfor their own drugs - a huge expense fordiseases such as cancer. Mr Rajbhar,who earns about Rs7,000 ($104) amonth when working full time, says hehas spent over Rs170,000 on his son'sfight against cancer, wiping out his sav-ings, and pushing the family into debt.

"I am in an extremely dire condition,"

he says softly. "The money I had savedto build a house is gone. I also have a21-year-old daughter to many off. All ofthat will be difficult now."

Such stories are all too common inIndia, where chronic neglect and lowfunding of public health are hamperingefforts to lift families out of poverty andstabilise the fragile middle class. Nearly

`You can't consideryoursellan emergingcountry,when millions gointo poverty because ofhealth incidents'

70 per cent of India's total health spend-ing comes out the pockets of patients'families, straining household budgetsand creating severe inequities in accessto care.

While wealthy Indians check intowell-equipped, private "super-special-ity" hospitals - including publicly listedcorporate chains such as Apollo Hospi-tals, Max India and Fortis Healthcare,the poor are relegated to cash-strapped,overstretched public facilities, wherethey must pay out of their own pocketfor drugs, diagnostic tests and evenbasic medical supplies.

A trmisformative programme

Narenclra Modi has ambitious plans totackle this health crisis. The prime min-ister's government is preparing theimminent rollout of a national healthprotection scheme, which aims to pro-vide India's poorest 100m households -an estimated 500m people - with insur-ance covering annual hospital expensesof up to Rs500,000.

Dubbed "Modicare" by local media,the programme - likely to be launchedthis year - is to allow beneficiaries toreceive "cashless" inpatient care at gov-ernment hospitals or approved privatefacilities, which will be paid at fixedrates for treating various diseases.

Trumpeted by the aclministration as"the world's largest government-funcleclhealthcare programme", the schemecomes as India is dealing with risinginciclents of non-commmnicable dis-eases - such as diabetes, heart diseaseand cancer - on top of its existing highburden of infectious diseases.

"This is something the country

needed," says Nilaya Varma, head ofKMPG India's healthcare practice. "Youcan't consider yourself an emerging ordeveloped country when millions gointo poverty because of health incidentsand the government can't providefor it."

Despite decades of high growth. Indiastill lags far behind other developingcountries such as China, Brazil andThailand in tending to the comprehen-sive health needs of its citizens. Due tothis neglect, India's health outconles inkey indicators such as maternal andinfant mortality are poorer than manyother countries at similar, or even lower,levels of development.

But Mr Modi is betting that the prom-ise of public support for citizens tosecure treatment at private hospitalswill not only transform India's health-care landscape but could yield rich elec-toral dividends when he seeks a second-term in nextyear's general elections.

Details of just how the scheme willwork are still being hammered out, asare the costs, which the government ini-tially estimates at $1.7bn for the first twoyears, although others believe it will besubstantially higher, and soar further asthe programme matures.

But Dr Vinod Paul, who is in charge ofthe health portfolio at the NITI Aayog -the government think-tank that hasdesigned the plan, calls it a "turningpoint" that will bring quality hospitalcare to millions of Indians for whom ithas so far been out of reach - or thecause of financial ruin.

"Access is the first issue," says Dr Paul."We are making secondaiy and tertiaryhospitalisation accessible to the peopleof India through the private and public

sector, without them having to pay forit, which they have never thought possi-ble. Right now, people don't even go fortreatment because they cannot go."

For Urmila Devi, who was recentlycamped outside Varanasi's private, 150-bed Heritage Hospital for days while hersix-year-old son was treated for anaffliction that hit his eyesight, such ascheme seems transformative. Her fam-ily sold their mud hut for Rs50,000 andborrowed from neighbours to fund herson's month-long odyssey through pub-lic and private hospitals. "I've lost eve-rything, but l'm just praying my son uti-i11be all right," she says.

More than insiu•ance

New Delhi estimates at least 63m vul-nerable Indians - or about 5 per cent ofthe population - are forced back intopoverty each year by unexpected, cata-strophic medical emergencies. At Herit-age Hospital, doctors say patients are"frequently" discharged too earlybecause they have run out of funds.

But experts warn that ensuringproper medical care for India's masseswill require far more than merely givingthem the capacity to cover the costs ofbeing hospitalised in the event of a criti-cal illness. "Health insurance is just afinancial instrument," says ShamikaRavi, a senior fellow at Brookings India,and a member of Mr Modi's economicadvisory council. "It's going to be asvaluable to the client, or the patient, asthe care that it can buy."

India's health system is severelystunted, with shortages of skilledpersonnel and hospitals. Indiahas just one doctor for evety1,600 people - below theWorld Health Organisa-tion's recommended levelof one per 1,000 - and anacute shortage of spe-cialists such as cardiolo-gists, oncologists andsurgeons. For many Incli-ans, the lack of appropriate

primary care - including early diagno-sis of chronic diseases and timely treat-ment of minor ailments - leads to moreserious and costly crises later.

Quality treatment is particularlyscarce in the impoverished northernHindi heartlands , where patients travellong distances to reach dilapidated gov-ernment hospitals , or wind up in tiny,unregulated private "nursing homes".

However, the government expects thescheme to trigger a surge in healthcareinvestment . "We have a public healthsystem in which we have been invest-ing," says Dr Paul. "In parallel , a privatesystem has come up. It is an asset of thenation , too. Even these two systems maynot be enough . There has to be an infu-sion of more resources and more infra-structure on the grou nd: "

But risks loom. With demand fortreatment rising, many experts warnhealthcare costs will inevitably rise -raising the burden on the governmentand pinching those not covered by the

The main lesson thatthe government shouldhave learnt is that youhave to have checks andvalances in place'

scheme. "It's just going to lead to allkinds of cost escalation," says Ms Ravi."That is the nature of an insurancedriven market. Neither the caregiver -the doctor - nor the patient has anyincentives to reduce costs."

Some critics believe New Delhi wouldbe better off investing more on modern-ising the dilapidated public healthcaresystem, where there are no incentives

to overtreat, and strengthening pri-mary and preventive care. "It's agood intention, but first build your

health system - which is full of inad-equacies of personnel, infrastructure

and medicine supply systems," saysSujatha Rao, India's former health sec-retary. "You have to invest in hospitals,otherwise prices will go so high you can'tcontain them."

New Delhi plans to spend $184m toenhance 150,000 public primary healthcentres, which are now focused mainlyon prenatal care and immunisations.

But Ms Rao says other aspects of thepublic care system should be bolsteredtoo. "We are too poor a country to just goon the idea that the private sector willdeliver," she says. "You have to haveboth public and private."

Reb*ttlating the system

India's experience with smaller-scaleinsurance schemes highlights theimplementation challenges ahead. In2008, New Delhi launched the Rash-triya Swasthya Bima Yojna, or RSBY, tocover up to Rs30,000 in hospitalisation

costs for poor families, including infor-mal workers. Today, about 36m familiesare ostensibly covered.

But Dr N Devadasan, co-founder ofthe Bangalore-based Institute of PublicHealth, says that years later many bene-ficiaries did not know how or where toaccess free treatment, and insteadwound up in private hospitals that werenot part of the programme, ultimatelypaying out of pocket for their care.

Dr Devadasan, who has tracked RSBYsince it began, says the failure to fullybrief poor, uneducated beneficiariesappeared to be a "deliberate strategy ofthe insurance companies" to minimiseclaims. "You distribute the card, but youdon't inform the patient or people whatit is for, or how it is used, and then claimsare less," he says.

Efforts to game the system were alsorampant, he says, with individuals andhospitals jointly forging medical recordsto share the subsequent payout. Sus-pecting wiclespreacl fraud, insurers reg-ularly delay payments, or reimburseonly a fraction of whatwas claimecl.

"The main lesson that the govern-ment should have learnt is that you haveto have checks and balances in place,"Dr Devadasan says. "There was nocapacity at the state level to do this, andit was kind of a free-for-all:'

In Delhi, Dr Paul acknowledges themagnitude of the challenges - includingthat of hospital regulation - but is confi-dent the government will tackle them.

"We will learn. We will continue tobuild the ship as we sail," Dr Paul says."If they cheat, which they will, and ifthey commit fraud, which they will, not

all but a few, there are ways to tackle itusing technology, using robust oversightand managerial mechanisms."

But Dr Paul insists that India is poisedto transform healthcare for the better.

"There is a huge vision behind it. Get-ting translated will take a while, but it isa game-changer," he says. "My guess isthat in 10 years' time, we will push ourlife expectancy by 10 years. And we willreduce our out-of-pocket payments forcatastrophic medical expenses by 50per cent."

India's health expenditure is among the lowestin the worldPublic health expenditure per capita, ($, at same purchasingpower level)

0 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 6,000

Switzerland

UK

UAE

Brazil

South Africa

China

India

Zimbabwe

C

India has made some progress on childmortality, but not as much as ChinaInfant mortality rate (rebased)

100

80

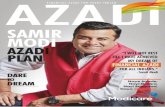

Patientsreceivingtreatment forinfections suchas dengue feverlie on the floorin SiliguriDistrictHospital, WestBengal. Below:Indian primeministerNarendra

Modi - 6etty Images

-Sub-Saharan Africa

Average for lowermiddle-income countries

South AsiaIndia

-China

60

40

20

1990 95 2000 05 10 16

Source: World Bank

r