years old at the time, on March 7, 1937 between 2 and · years old at the time, on March 7, 1937...

Transcript of years old at the time, on March 7, 1937 between 2 and · years old at the time, on March 7, 1937...

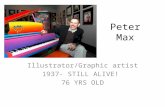

32 JOMSA

years old at the time, on March 7, 1937 between 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning, the Wolff family was roused from bed and forcefully evicted onto the street. The family, Kurt, wife Elsie, children Leonardo, Magdalena, Arno and Kurt’s parents were marched to the railroad station, loaded on box cars with others from their community, and transported to Orangenburg.

At the time Orangenburg was a detention camp which later became known as Sachsenhausen concentration camp, the principal camp for the Berlin area. In the early stages (1932-1933), along with Jews, political opponents and real or perceived criminal offenders were also incarcerated. By the end of 1936 the camp held 1,600 prisoners including homosexuals, Jehovah Witnesses, and other “asocials.” The Wolff family was incarcerated in the camp for seven months from March to October 1937.

Arno, who is now 82 years-old, shared his camp experience with the author. Arno needs walking sticks because of back problems he attributes to abuse in the camp. He vividly remembers being forced to carry rocks from one location to another. If children were slow in their tasks, they were struck in the small of their back by a Kapo wielding a sturdy metal baton. This was strenuous, grueling work for older children, let alone a 4-year old.

Life in the camp was grim with some internees being released in exchange for a stated intent to emigrate. Not knowing their fate was haunting, however a most fortunate thing happened. One of only three surviving officers from Wolff’s World War I unit was the camp commander’s adjutant who recognized Wolff. Having an administrative position, they conspired to put papers together to get the Wolff family out of the camp. On the day of departure, the authorities intervened forcing the family to make a wrenching decision, Mr. & Mrs. Wolff could leave with only one of their three children. The youngest Arno was chosen (it’s unknown who chose Arno, his parents or camp authorities). According to Red Cross records the other two children and Wolff’s parents were taken to Thersienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. They most likely went to crematorium #1 in Birkenau at Auschwitz. Of the 187 members of the extended Wolff family only 13 survived the Holocaust.

Returning to Wolff’s diary he recounted a touching 1917 Christmas scene:

I am now looking at my “Christmas gifts” and notice, that for me it is half a pencil and a rotten apple. Nevertheless, I thank the benevolent donor for it and

she generously compensates me on New Years Eve with books and chocolate. I am ask for a photograph of her later on, assuming to see a young girl. Only then I learned that she is almost 60 years old, her name is Carola Kampfmiller from Hocklingen near Hemer in Westphalia.

As a young soldier Wolff in all likelihood visualized a youthful fraulein who he looked forward to show his appreciation for his gifts. Remarkably her name and location has survived.

Immediately upon release from Orangenburg Kurt made plans to leave Germany, obtaining in Berlin a passport and exit papers to the United States for 10,000 Reich marks. Still a visa was a problem – an American sponsor was needed.

Elsie Wolff contacted her Aunt Augusta and Uncle Sol who owned the Life Sun Insurance Company in Baltimore, Maryland to sponsor their visas. They, along with many others at the time didn’t understand what was happening in Germany nor were they keen on sponsoring visas that made them financially responsible for the holders. Reluctantly they sponsored a visa for Kurt, a wage earner but not or their niece or nephew.

With visa in hand, on February 22, 1938 Kurt emigrated to America, driven to obtain additional visas for his family to join him. During the next year Mrs. Wolff and son Arno resided with her parents and witnessed the frightening devastation of Jewish business and synagogues during Kristalnacht on November 9-10, 1939. Living in the small apartment young Arno was responsible for keeping the windows covered with damp towels to smother conversation from suspicious neighbors.

Finally, after 14 months visas arrived for Mrs. Wolff and son Arno (Figure 5). With documents in hand they boarded the last American ship out of Hamburg, the SS United States, on April 19, 1939 before authorities closed the port at noon. Five months later Germany attacked Poland. The voyage to New York allowed new found freedoms, not having to talk in whispers, not being alarmed by a knock on their cabin door and freedom to talk to other passengers. Most guarded however were conversations with one particular passenger who befriended Mrs. Wolff. He revealed he was a Gestapo agent also escaping to America. The only major concern was Arno’s long trips exploring the ship’s engine rooms when mother had to send a steward to find him.

With Wolff’s familiarity with the tobacco business he

Vol. 66, No.4 (July-August 2015) 33

was advised to go to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a major hub of tobacco growing and manufacturing markets. He readily found employment with the Bayuk Cigar Company. Not pleased with his menial tobacco job, he

Figure 5: Cover of the passports for the Wolff family. Mrs. Wolff’s 1938 passport is at right and Kurt Wolff’s 1939 passport is at left.

Figure 6: The Walters and Fisher Tire Company in the 1960s. Kurt Wolff is at far right.

secured a bookkeeper’s position with Walters and Fisher Tire Company on North Prince Street in Lancaster (Figure 6).

34 JOMSA

Kurt was an industrious, respected worker, who related well with fellow employees and customers and learned the tire business from rubber tree to final product. He became a United States citizen. Over the years he rose to manager and became the co-owner of the tire retail and recapping business working there until retirement.

In 1984 Kurt and wife Elsie, being displaced persons, qualified for certain benefits and returned to Germany to live out their lives. Kurt passed away in 1989. In 1990 Elsie returned to the United States to live with her son Arno until her death in 1996. She now rests beside

BOOK REVIEW

Wojciech Stela. Polskie Ordery I Odznaczenia Polnische Orden und Ehrenzeichen: Polish Orders and Medals; Ордена и Медали Пол’ши, Vol. IV. Warsaw, Poland: Wojciech Stela, 2014. Hardback, 481 pages, profusely illustrated. Available on eBay.

Wojciech Stela from Poland has recently published a fourth volume of his work on Polish orders and medals. It is another masterpiece of research, data and photography.

He dedicates the first 126 pages to the Order of the Virtuti

her loving husband in Germany. Her surviving son, 82 years old Arno, served with the United States Army in Korea, earned a Ph. D. in English literature, and resides in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

An Iron Cross is a prized possession. One with such a preserved rich history supported with validation is extraordinary. Lieutenant Kurt Wolff’s Iron Crosses help to recount this story of a courageous, proud, decorated soldier who fought for his fatherland but was forced to leave his beloved country because of his religion during Germany’s dark days.

Militari from its founding in 1792 to end of the 1831 era. Color illustrations of almost every available kingdom-era Virtuti Militari is presented. These are excellent examples of Polish, French and Austrian jewelers’ productions. The history of each is given with details as to the size, class, metallic content and current market price. The fact that Stela presents his information in four languages, Polish, English, German and Russian permits a wide dissemination of knowledge across many cultures.

The remaining Virtuti Militari crosses in existence today are indeed national treasures taking under consideration that the Czar forbid their wearing and ordered them to be retuned at risk of imprisonment or worse. Hundreds of reluctant recipients were forced to give up their awards after receiving them two years earlier.

The next topic covered in pages 131 tthrough 238 is the Legion era from 1914-1918. Every badge is shown with its information. The last section (pages 239 through 479) is entitled “Warfare to Establish the Polish Border 1918-1921.” It is a very impressive historical presentation that describes the badges issued during the era in which Poland fought for the national borders which it still occupies today. After 125 years of foreign occupation, Poland regained in 1918 her independence and freedom and most of her ancient lands.

Mr. Stela is to be commended for his hard work to preserve for posterity this important part of Polish military history. It is heartwarming to see a member of the younger generation value highly his Polish roots. He is a patriotic young man who has made a serious contribution to the history of Polish decorations.

Reviewed by Prof. Dr. Zdzislaw P. Wesolowski

![DEEDS REGISTRIES ACT NO. 47 OF 1937 - Shepstone & Wylie · DEEDS REGISTRIES ACT NO. 47 OF 1937 [View Regulation] [ASSENTED TO 19 MAY, 1937] [DATE OF COMMENCEMENT: 1 SEPTEMBER, 1937]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f0aaf9f7e708231d42cd69c/deeds-registries-act-no-47-of-1937-shepstone-wylie-deeds-registries-act.jpg)