Ted Adelson’s checkerboard illusion. Motion illusion, rotating snakes.

Wy Checkerboard Govt Opp to Pi Motion

-

Upload

agracekuhn -

Category

Documents

-

view

24 -

download

0

Transcript of Wy Checkerboard Govt Opp to Pi Motion

CHRISTOPHER A. CROFTS United States Attorney NICHOLAS VASSALLO (WY Bar No. 5-2443) Assistant United States Attorney P.O. Box 668 Cheyenne, WY 82003-0668 Telephone: 307-772-2124 [email protected] SAM HIRSCH, Acting Assistant Attorney General SETH M. BARSKY, Section Chief COBY HOWELL, (Wy. Bar No. 6-3589) Senior Trial Attorney U.S. Department of Justice Environment & Natural Resources Division Wildlife and Marine Resources Section c/o U.S. Attorney’s Office 1000 SW Third Avenue Portland, OR 97204-2902 (503) 727-1000 (503) 727-1117 (fx) [email protected] MICHAEL D. THORP Senior Trial Attorney Environment and Natural Resources Division Natural Resources Section U.S. Department of Justice 601 D. Street, N.W., Room 3112 Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 305-0456 [email protected] Attorneys for Federal Respondents

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF WYOMING

AMERICAN WILD HORSE PRESERVATION CAMPAIGN, et al., Petitioners,

) ) ) ) )

Case No. 1:14-cv-152-F

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 1 of 36

v. S.M.R. JEWELL, Secretary of the United States Department of the Interior, et al., Respondents. ___________________________________

) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) )

FEDERAL RESPONDENTS’ OPPOSITION TO PETITIONERS’ MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 2 of 36

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1

II. LEGAL BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................1

A. The Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act .....................................................1

B. Checkerboard Land Authorities ...............................................................................3

C. NEPA .......................................................................................................................4

III. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................5

A. Wyoming Checkerboard Lands and Wild Horses ...................................................5

1. RSGA v. Salazar ..........................................................................................6

2. Implementation of the Consent Decree........................................................9

3. BLM’s Proposed 2014 Gather ...................................................................10

IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW ...............................................................................................10

A. Preliminary Injunction Standard ............................................................................10

B. Judicial Review Under the Administrative Procedure Act ....................................12

V. ARGUMENT ....................................................................................................................13

A. Petitioners Will Not Succeed on the Merits ...........................................................13

1. BLM Fully Complied with NEPA .............................................................13

a. BLM’s Evaluation of Environmental Significance was Appropriate ....................................................................................13 b. BLM was not required to prepare an Environmental Assessment .....................................................................................14

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 3 of 36

ii

c. BLM did not depart from its own guidance, nor did it depart from past practice ................................................................16 2. BLM Complied with the Wild Horses Act ................................................19 B. Petitioners Fail to Demonstrate The Likelihood of Any Irreparable Harm ......................................................................................................................22 C. The Balance of the Equities Favor Allowing the 2014 Gather to Proceed ............25 VI. CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................25.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 4 of 36

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Federal Cases

Airport Neighbors Alliance v. United States, 90 F.3d 426 (10th Cir. 1996) ............................................................................................ 12

Am. Horse Prot. Ass’n v. Frizzell, 403 F. Supp. 1206 (D. Nev. 1975) ...................................................................................... 3

Am. Horse Prot. Ass’n v. Watt, 694 F.2d 1310 (D.C. Cir. 1982) .......................................................................................... 3

American Horse Protection Assoc. v. Andrus, 460 F. Supp. 880 (D. Nev. 1978) ...................................................................................... 19

Amoco Prod. Co. v. Village of Gambell, 480 U.S. 531 (1987) ..................................................... 22

Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997) .......................................................................................................... 18

Baltimore Gas & Elec. Co. v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 462 U.S. 87 (1983) ............................................................................................................ 12

Camfield v. United States, 167 U.S. 518 (1897) ........................................................................................................... 3

Chem. Weapons Working Grp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Army, 111 F.3d 1485 (10th Cir. 1997) ........................................................................................ 11

Christensen v. Harris Cnty., 529 U.S. 576 (2000) .......................................................................................................... 16

Citizens Comm. to Save Our Canyons v. U.S. Forest Serv., 297 F.3d 1012 (10th Cir. 2002) ....................................................................... 5, 14, 15, 18

Citizens to Pres. Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971) .......................................................................................................... 12

Cloud Found. v. BLM, 802 F. Supp. 2d 1192 (D. Nev. 2011) ............................................................................... 25

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 5 of 36

iv

Cody Labs. v. Sebelius, NO. 10-CV-147-ABJ11, 2010 WL 3119279 (D. Wyo. July 26, 2010) ............................ 24

Colo. Wild v. U.S. Forest Serv., 435 F.3d 1204 (10th Cir. 2006) .................................................................................... 4, 13

Colorado Wild Horse and Burro Coalition v. Salazar, 639 F. Supp. 2d 87 (D.D.C. 2009) .................................................................................... 21

Dominion Video Satellite, Inc. v. Echostar Satellite Corp., 356 F.3d 1256 (10th Cir. 2004) ........................................................................................ 22

FCC v. Fox Television Stations, 556 U.S. 502 (2009) .......................................................................................................... 17

Fund for Animals v. BLM, 460 F.3d 13 (D.C. Cir. 2006) .......................................................................................... 1, 2

Fund for Animals, Inc. v. Lujan, 962 F.2d 1391 (9th Cir. 1992) .......................................................................................... 22

Greater Yellowstone Coal. v. Flowers, 321 F.3d 1250 (10th Cir. 2003) ....................................................................................... 11

GTE Corp. v. Williams, 731 F.2d 676 (10th Cir. 1984) .......................................................................................... 11

Habitat for Horses v. Salazar, 745 F. Supp. 2d 438 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) ............................................................................... 25

High Country Citizens’ Alliance v. U.S. Forest Serv., 203 F.3d 835, No. 97-1373, 2000 WL 147381 (10th Cir. Feb. 7, 2000) ...................... 5, 19

In Defense of Animals v. Salazar, 675 F. Supp. 2d 89 (D.D.C. 2009) .................................................................................... 25

In Defense of Animals v. U.S. Dep’t of Interior, 737 F. Supp. 2d 1125 (E.D. Cal. 2010)............................................................................. 25

Kleppe v. Sierra Club, 427 U.S. 390 (1976) ......................................................................................................... 12

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 6 of 36

v

Leo Sheep Co. v. United States, 440 U.S. 668 (1979) ............................................................................................................ 4

Long Island Care at Home, Ltd. v. Coke, 551 U.S. 158 (2007) .......................................................................................................... 18

Lust v. Merrell Dow Pharms., 89 F.3d 594 (9th Cir. 1996) .............................................................................................. 15

Marsh v. Or. Natural Res. Council, 490 U.S. 360 (1989) ................................................................................................... 12, 13

Mazurek v. Armstrong, 520 U.S. 968 (1997) ......................................................................................................... 11

Morris v. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Comm’n, 598 F.3d 677 (10th Cir. 2010) .......................................................................................... 12

Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29 (1983) ............................................................................................................ 12

Mountain States Legal Found. v. Hodel, 799 F.2d 1423 (10th Cir. 1986) .................................................................................... 4, 20

Olenhouse v. Commodity Credit Corp., 42 F.3d 1560 (10th Cir. 1994) ................................................................................ 5, 12, 19

Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians v. Pierce, 253 F.3d 1234 (10th Cir. 2001) ........................................................................................ 22

Reuters Ltd. v. United Press Int’l, Inc., 903 F.2d 904 (2d Cir. 1990).............................................................................................. 22

Rock Springs Grazing Ass’n v. Salazar, 935 F. Supp. 2d 1179 (D. Wyo. 2013) ....................................................................... passim

RoDa Drilling Co. v. Siegal, 552 F.3d 1203 (10th Cir. 2009) .................................................................................. 11, 22

SCFC ILC, Inc. v. Visa USA, 936 F.2d 1096 (10th Cir. 1991) ......................................................................................... 11

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 7 of 36

vi

Sierra Club v. Bostick, NO. VIV-12-742-R, 2013 WL 6858685 (W.D. Okla. Dec. 30, 2013) ............................. 19

Sprint Spectrum, L.P. v. State Corp. Comm’n, 149 F.3d 1058 (10th Cir. 1998) ........................................................................................ 11

Town of Superior v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Serv., 913 F. Supp. 2d 1087 (D. Colo. 2012) .............................................................................. 14

U.S. ex rel. Bergen v. Lawrence, 848 F.2d 1502 (10th Cir. 1988) ........................................................................................... 4

United Tribe of Shawnee Indians v. United States, 253 F.3d 543 (10th Cir. 2001) .................................................................................... 22, 25

Utah Envtl. Cong. v. Russell, 518 F.3d 817 (10th Cir. 2008) .................................................................................... 12, 15

Utah v. Babbitt, 137 F.3d 1193 (10th Cir. 1998) ....................................................................................... 12

Wild Earth Guardians v. U.S. Forest Serv., 668 F. Supp. 2d 1314 (D.N.M. 2009) .............................................................................. 19

Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 555 U.S. 7 (2008) ........................................................................................................ 11, 25

Statutes

5 U.S.C. §§ 701-706 ..................................................................................................................... 12

16 U.S.C. § 1331 ............................................................................................................................. 1

16 U.S.C. § 1332(c) ........................................................................................................................ 1

16 U.S.C. § 1332(f) ......................................................................................................................... 2

16 U.S.C. § 1333 .................................................................................................................... passim

16 U.S.C. § 1333(a) .................................................................................................................. 1, 21

16 U.S.C. § 1333(b)(1) ................................................................................................................... 2

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 8 of 36

vii

16 U.S.C. § 1334 ............................................................................................................. 2, 6, 20, 21

43 U.S.C. § 1061-65 ....................................................................................................................... 3

12 Stat. 489 ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Regulations

40 C.F.R. § 1500.1(c)...................................................................................................................... 4

40 C.F.R. § 1507.3(b)(2) ........................................................................................................... 5, 13

40 C.F.R. § 1508.4 .................................................................................................................. 13, 15

43 C.F.R. § 46.205(c).................................................................................................................... 13

43 C.F.R. § 4700.0-5(d) .................................................................................................................. 2

43 C.F.R. § 4710.1 .......................................................................................................................... 2

43 C.F.R. § 4710.3-1 ....................................................................................................................... 1

43 C.F.R. § 4710.4 .......................................................................................................................... 2

43 C.F.R. § 4720.2-1 ................................................................................................................. 2, 20

43 C.F.R. § 4730.1 .................................................................................................................... 3, 20

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 9 of 36

1

I. INTRODUCTION

Sally Jewell, Secretary of the Department of the Interior (“Secretary”) and Neil Kornze,

Director of the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) (collectively “Federal Respondents”)

oppose Petitioners’ Motion for a Temporary Restraining Order and/or Preliminary Injunction.

Petitioners have alleged that Federal Respondents are violating the National Environmental

Policy Act (“NEPA”) and Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act (“Wild Horses Act”). For

the reasons discussed below, Petitioners have failed to demonstrate they are likely to succeed on

the merits of their claim and have also failed to show any irreparable harm to their interests.

Moreover, BLM’s proposed gather and removal furthers the public interest and the equities tip

sharply in favor of allowing this gather to proceed. The Court should deny Petitioners’ motion

for emergency injunctive relief.

II. LEGAL BACKGROUND

A. The Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act

In 1971 Congress passed the Wild Horses Act, 16 U.S.C. § 1331 et seq., because wild

horses were vanishing from the West and it wished to preserve these animals as “living symbols

of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West.” 16 U.S.C. § 1331. To accomplish this task, it

directed the Secretary to provide for their protection and management. Id. at § 1331. In 1978,

Congress passed amendments to the Wild Horses Act that provided the Secretary with greater

authority and discretion to manage and remove horses from rangeland. Id.

There are two distinct obligations under the Wild Horses Act. The first involves

management on federal public lands. Section 3 of the Wild Horses Act directs the Secretary of

the Interior to “manage wild free-roaming horses and burros in a manner that is designed to

achieve and maintain a thriving natural ecological balance on the public lands.” 16 U.S.C. §

1333(a); see also Fund for Animals v. BLM, 460 F.3d 13, 15 (D.C. Cir. 2006). “The Bureau (as

the Secretary’s delegate) carries out this function in localized ‘herd management areas’

(“HMAs”).” Id.; see also 16 U.S.C. § 1332(c); 43 C.F.R. § 4710.3-1. HMAs are generally

established in broader land use plans. Fund for Animals, 460 F.3d at 15; see also 43 C.F.R. §

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 10 of 36

2

4710.1. “Responsibility for a particular herd management area rests with [BLM’s] local field and

state offices.” Fund for Animals, 460 F.3d at 15.

In each HMA, BLM officials are afforded discretion to determine their own methods for

computing “appropriate management levels” (“AMLs”) for the wild horse populations they

manage. Id. at 16; see also 16 U.S.C. § 1333(b)(1). When wild horse populations exceed the

carrying capacity of the range, or when wild horses stray outside of a designated HMA, BLM

may remove them. See 16 U.S.C. § 1332(f) (defining “excess animals” as “wild free-roaming

horses or burros (1) which have been removed from an area by the Secretary pursuant to

applicable law, or (2) which must be removed from an area in order to preserve and maintain a

thriving natural ecological balance and multiple-use relationship in that area”); 43 C.F.R. §

4710.4 (management of wild horses “shall be undertaken with the objective of limiting the

animals' distribution to herd areas”); 43 C.F.R. § 4700.0-5(d) (herd areas are the “geographic

area identified as having been used by a herd as its habitat in 1971”).

BLM also has distinct and independent duties with regard to wild horses on private lands.

Under Section 4 of the Act, if wild horses “stray from public lands onto privately owned land,

the owners of such land may inform the nearest Federal marshal or agent of the Secretary, who

shall arrange to have the animals removed.” 16 U.S.C. § 1334. The Act further provides

“[n]othing in this section shall be construed to prohibit a private landowner from maintaining

[wild horses] on his private lands, or lands leased from the Government, if he does so in a

manner that protects them from harassment, and if the animals were not willfully removed or

enticed from the public lands.” Id.

BLM has interpreted this statutory provision by promulgation of a regulation, which

provides: “Upon written request from the private landowner to any representative of the Bureau

of Land Management, the authorized officer shall remove stray wild horses and burros from

private lands as soon as practicable.” 43 C.F.R. § 4720.2-1. This request must “indicate the

numbers of wild horses or burros, the date(s) the animals were on the land, legal description of

the private land, and any special conditions that should be considered in the gathering plan.” Id.

There is nothing in the statute or regulations that require BLM to remove wild horses from

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 11 of 36

3

private lands and return them to public lands. The only limitation on the private removal of wild

horses is that, unless an act of mercy is required, wild horses cannot be destroyed without

approval from the authorized officer. 43 C.F.R. § 4730.1

Congress has provided BLM with a significant amount of discretion as to how it manages

and removes wild horses from public and private lands. See, e.g., Am. Horse Prot. Ass’n v.

Frizzell, 403 F. Supp. 1206, 1217 (D. Nev. 1975). In short, BLM, in its expert capacity as the

federal agency in charge of managing and removing wild horses, is entitled to deference in

deciding when and how to remove wild horses from the range. Am. Horse Prot. Ass’n v. Watt,

694 F.2d 1310, 1318 (D.C. Cir. 1982).

B. Checkerboard Land Authorities

“Checkerboard” lands became prominent after the passage of the Pacific Railroad Act of

1862. 12 Stat. 489. Under Section 3 of this Act, the Union Pacific Railroad Company was

granted “every alternate section of public land, designated by odd numbers, to the amount of five

alternate sections per mile on each side of said railroad, on the line thereof, and within the limits

of ten miles on each side of said road, not sold, reserved, or otherwise disposed of by the United

States . . . .” Id. at 492. This grant of land resulted in a pattern of alternatively held public and

private lands which is commonly referred to as the Checkerboard.

A significant problem with the Checkerboard was that it allowed private landowners to

build fences, entirely on their own private property, which enclosed and blocked access to public

lands. This problem was addressed by the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885. 43 U.S.C. § 1061-

65. Under this Act, “[a]ll inclosures of any public lands in any State or Territory of the United

States, heretofore or to be hereafter made . . . are hereby declared to be unlawful, and the

maintenance, erection, construction, or control of any such inclosure is hereby forbidden and

prohibited.” Id. at § 1061; see also Camfield v. United States, 167 U.S. 518 (1897) (upholding

the constitutionality of the Act and declaring a fence that was located entirely on private

checkerboard lands a nuisance and illegal).

The Tenth Circuit and the District of Wyoming, in particular, have been at the forefront

of reconciling the difficult land management issues associated with balancing the rights of

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 12 of 36

4

private landowners and the government within the Checkerboard. In Leo Sheep Co. v. United

States, 440 U.S. 668 (1979), the Supreme Court reversed the Tenth Circuit, finding that the

government did not have the right to erect a road through private Checkerboard land in order to

create public access to Seminoe Reservoir. Id. at 682. The Court rejected arguments that the

government had reserved a property interest not enumerated in the patent. Id. at 687-688 (“This

Court has traditionally recognized the special need for certainty and predictability where land

titles are concerned, and we are unwilling to upset settled expectations to accommodate some ill-

defined power to construct public thoroughfares without compensation.”). At the same time, the

Tenth Circuit has consistently recognized that private landowners may not erect fences on

private lands to exclude wildlife, including wild horses, from accessing public lands. U.S. ex rel.

Bergen v. Lawrence, 848 F.2d 1502, 1506 (10th Cir. 1988) (rejecting the argument that the

Unlawful Inclosures Act was repealed by implication and holding that private landowners may

not erect a fence to exclude antelope from the Checkerboard). Similarly, the Tenth Circuit has

held that wild horses grazing on private land within the Checkerboard is not an unconstitutional

taking warranting compensation. Mountain States Legal Found. v. Hodel, 799 F.2d 1423, 1431

(10th Cir. 1986) (“In view of the important governmental interest involved here, we conclude that

no taking has occurred . . . .”).

C. NEPA

“NEPA was enacted to regulate government activity that significantly impacts the

environment and ‘to help public officials make decisions that are based on an understanding of

environmental consequences, and take actions that protect, restore, and enhance the

environment.’” Colo. Wild v. U.S. Forest Serv., 435 F.3d 1204, 1209 (10th Cir. 2006), quoting

40 C.F.R. § 1500.1(c). The Council on Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) administers NEPA and

promulgates regulations that are binding in federal agencies. Id. “When an agency identifies

certain actions that do not have any significant effect on the environment, the agency may

classify those actions as categorical exclusions. Under NEPA and CEQ regulations, if an action

falls within a particular [Categorical Exclusion], the agency need prepare neither an

[Environmental Impact Statement] nor an [Environmental Assessment]” for that action. Id., 40

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 13 of 36

5

C.F.R. § 1507.3(b)(2), Citizens Comm. to Save Our Canyons v. U.S. Forest Serv., 297 F.3d 1012,

1023 (10th Cir. 2002) (federal regulations delegate to individual agencies the responsibilities for

defining what type of actions may be categorically excluded from more detailed NEPA review).

“Once an agency establishes categorical exclusions, its decision to classify a proposed

action as falling within a particular categorical exclusion will be set aside only if a court

determines that the decision was arbitrary and capricious.” Id. (citations omitted). When

reviewing an agency’s interpretation and application of its categorical exclusions, courts are

deferential. Id. Under this standard, the court must “ascertain whether the agency examined all

the relevant data and articulated a rational connection between the facts found and the decision

made.” High Country Citizens’ Alliance v. U.S. Forest Serv., 203 F.3d 835 (Table), No. 97-

1373, 2000 WL 147381, at *4 (10th Cir. Feb. 7, 2000) (unpublished), quoting Olenhouse v.

Commodity Credit Corp., 42 F.3d 1560, 1574 (10th Cir. 1994).

III. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

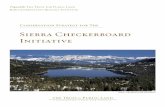

A. Wyoming Checkerboard Lands and Wild Horses

BLM is responsible for managing 16 Herd Management Areas in Wyoming, five of

which are in BLM’s Rock Springs Management Area (“Management Area”) in the southwestern

part of the state. Rock Springs Grazing Ass’n v. Salazar, 935 F. Supp. 2d 1179 (D. Wyo. 2013)

(“RSGA”). 1 The five HMAs within the Management Area are Divide Basin, Little Colorado,

Salt Wells Creek, White Mountain, and part of Adobe Town. Portions of four out of five of the

Rock Springs District HMAs (including Adobe Town, Divide Basin, Salt Wells Creek, and

White Mountain) are within Wyoming Checkerboard lands.

1 Unless otherwise noted, factual support for this background section is taken from RSGA v. Salazar, 935 F. Supp. 2d 1179, Federal Respondents’ brief in opposition, RSGA, 2:11-cv-00263-NDF (ECF 67), and the supporting administrative record in that case. Federal Respondents incorporate by reference that administrative record. A copy of the administrative record is available upon request to the parties, or if the Court would like Federal Respondents to file a copy in this case, we will do so promptly.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 14 of 36

6

Within parts of these HMAs, RSGA owns private lands within the Checkerboard and

leases other lands from Anadarko Land Corp. Id. at 1182 n.2. RSGA uses these private lands

for grazing cattle and sheep. RSGA also holds grazing permits for BLM-managed public lands

in the Checkerboard. Wild horses and RSGA-owned livestock graze on the Checkerboard and,

because it is not fenced, wild horses can move throughout this area, as well as to and from solid-

block public lands surrounding the Checkerboard. Id.

In 1975, four years after the enactment of the Wild Horses Act, RSGA requested that

BLM remove wild horses from the Checkerboard. BLM responded, explaining that it was aware

of the need to remove wild horses, but that it had insufficient funds to do so. Unsatisfied with

this response, on September 20, 1979, RSGA and Mountain States Legal Foundation filed suit

against the Secretary of the Interior, the United States Marshal for the District of Wyoming, and

the United States, alleging that the Secretary failed to: (1) comply with 16 U.S.C. § 1333; (2)

remove horses from private lands at RSGA’s request, under 16 U.S.C. § 1334; and (3) prevent

damage Checkerboard lands, which constitutes an unconstitutional taking. Id. at 1183.

On March 13, 1981, Judge Kerr’s initial order in the case directed that “the Rock Springs

District office of the [BLM] shall within one year from the date of this Order remove all wild

horses from the checkerboard grazing lands in the Rock Springs District except that number

which the [RSGA] voluntarily agrees to leave in said area.” Id. (emphasis added).

In September 1984, the parties filed a stipulation with the Court agreeing that it would be

in “the interests of justice” to further amend BLM’s obligations under the Court’s 1981 order. It

appears the Court entered the order in the fall of 1984, and BLM complied in 1985 by removing

all wild horses from the Checkerboard except those horses that RSGA allowed to remain. Id. at

1183-84.

1. RSGA v. Salazar

On October 4, 2010, RSGA sent a letter to BLM’s District Manager demanding the

removal of all wild horses from lands it owned or leased under 16 U.S.C. § 1334. Id. at 1184.

BLM responded to RSGA’s letter on February 7, 2011. RSGA was not satisfied with BLM’s

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 15 of 36

7

response and, on July 27, 2011, filed a petition in this Court seeking to enforce the 1981 order

against Secretary and BLM. RSGA, ECF No. 1. Among other requests for relief, RSGA sought

an order directing BLM to remove all wild horses from RSGA’s lands within one year. Id.

After some preliminary proceedings, the Court allowed many of the Petitioners in the

present case to intervene. RSGA, ECF 32 at 8.2 The parties then proceeded to brief the merits.

During the course of that briefing, BLM filed a declaration from Edwin Roberson committing to

a schedule for the removal of all wild horses from RSGA’s Checkerboard lands by September

2015, with follow-up gathers occurring until September 2018. RSGA, ECF 67 at 53 (Edwin

Roberson Decl. ¶ 9).

Following a hearing on the merits, BLM and RSGA requested an opportunity to negotiate

a compromise that would allow BLM to maintain some wild horses on RSGA’s private lands

within the Checkerboard in return for a commitment to remove the remaining horses. Over the

course of months, BLM and RSGA were able to reach a proposed compromise where, among

other commitments, BLM agreed to “remove all wild horses located on RSGA’s private lands,

including Wyoming Checkerboard lands, with the exception of those horses found within the

White Mountain [HMA].” RSGA, ECF 92-1 at 4, ¶ 1.

On January 11, 2013, BLM provided the Intervenors with a copy of the draft agreement

and requested comments on the proposal. RSGA, ECF 92 at 2. After approximately a month of

review, Intervenors indicated that they would not provide any comments to BLM and RSGA on

2 The Court allowed the International Society for the Protection of Mustangs and Burros (“ISPMB”), the American Wild Horse Preservation Campaign (“AWHPC”), and the Cloud Foundation to intervene. RSGA, ECF 32. In support of their motion to intervene, these organizations filed the declarations of Karen Sussman, Suzanne Roy, and Ginger Kathrens. RSGA, ECF 17. Most of the Petitioners in the present case (AWHPC, Cloud Foundation, Ginger Kathrens) are the same Intervenors that participated in RSGA v. Salazar, and it is unclear whether the remaining Petitioners (Return to Freedom, Carol Walker, Kimerlee Curyl) are in privity with these organizations or even participated in the previous litigation. Although Federal Respondents do not raise a preclusion defense at this time, we expressly reserve the right to do so at a later date.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 16 of 36

8

the draft consent decree, but would be filing objections with the Court. On February 12, 2013,

BLM and RSGA filed a joint motion to dismiss with the proposed consent decree. RSGA, ECF

81. On February 25, 2013, Intervenors filed their opposition to the proposed consent decree.

RSGA, ECF 86.

Among other challenges, Intervenors argued that BLM could not lawfully commit to

removing all wild horses from Checkerboard lands because there was no practical means of

differentiating between horses on private and public land. RSGA, ECF 86-1 at 8 (“because of the

configuration of the Checkerboard, there simply is no practical way to differentiate between

horses that are on the private lands versus those that are on the public lands at any one point in

time . . .”). Indeed, Intervenors filed a declaration explaining, in detail, how it was impossible to

differentiate between private and public obligations on the Checkerboard. Id. (“it is illogical for

BLM to commit to removing wild horses that are on ‘private’ lands RSGA owns or leases

because those same horses are likely to be on public BLM land (for example, the Salt Wells,

Adobe Town, Great Divide, and White Mountain HMAs) earlier in that same day or later that

same evening”)) (quoting Eisenhaur Decl. ¶ 4). BLM did not dispute that it could not

differentiate between horses on private and public lands within the Checkerboard at specific

point in time, but argued that this practical reality did not absolve BLM from complying with

Section 4 of the Wild Horses Act. RSGA, ECF 88 at 6-7 (Intervenors’ objections “are all

premised on the belief that BLM must ignore this statutory provision and treat all Checkerboard

lands as if they were public lands.”).

Before entering the consent decree, the Court addressed this argument:

While the Court fully appreciates the land management challenges presented by checkerboard ownership, those problems do not deprive RSGA of its rights as a private landowner under Section 4 of the Wild Horses Act, nor the deference due the BLM as the agency with substantial expertise in the management of the HMAs. The BLM is statutorily obligated to manage wild horses in this area consistent with RSGA’s Section 4 legal rights notwithstanding the RMP herd management objectives for federal land, or the particular management challenges presented.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 17 of 36

9

RSGA, 935 F. Supp. 2d at 1187-88. The Court also correctly recognized the value in the consent

decree because it “allows the BLM to maintain [205-300] wild horses on RSGA’s private lands”

even though RSGA could ask BLM to remove all wild horses. Id. at 1188.

2. Implementation of the Consent Decree

After the Court approved the consent decree, BLM conducted a gather in 2013. BLM

gathered 668 wild horses, but removed only 586 from the Adobe Town and Salt Wells HMAs.

See the attached declaration of Kimberlee D. Foster, BLM’s Rock Springs Field Office Manager

(hereinafter “Foster Decl”) ¶ at 19, Ex. 1 at 1 (May 12, 2014, Letter to RSGA from BLM). BLM

returned the remaining horses to the HMAs because it wanted to leave the population at the “low

end of the AML” in the RMP. Id. RSGA promptly objected to BLM’s 2013 gather, and

particularly objected to BLM returning gathered horses to the range because they would

invariably return to RSGA’s private lands.

On February 4, 2014, RSGA invoked the dispute resolution procedure in the consent

decree and sent BLM a letter alleging noncompliance with paragraph 1. Ex. 2 (February 4, 2014,

Letter to BLM from RSGA). RSGA argued that BLM had committed to removing all wild

horses from the Checkerboard area in Adobe Town and Salt Wells HMAs, and that by returning

horses to the range to achieve the low end of AML, BLM did not fulfill its obligations in the

consent decree. See e.g. id. at 5 (“gathering only a minimum number of wild horses and leaving

the rest is not compliance with the Consent Decree”).

On May 12, 2014, BLM responded to these allegations. Ex. 1. BLM did not agree with

many of the assertions in the letter, but recognized that it had “agreed to remove all wild horses

on RSGA’s private lands, including Checkerboard lands, in accordance with the schedule set

forth in the Consent Decree, Paragraph 5,” id., and that it had “revaluated the 2013 ATSW

gather, and acknowledge[d] that it should have removed all horses from RSGA’s lands in the

HMA.” Id. at 1. To ensure future compliance with the consent decree, BLM stated: “In light of

comments received during scoping [on the proposed 2014 Gather], as well as your letter of

February 4, the BLM is re-formulating its plan for the 2014 Divide Basin gather. In doing so,

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 18 of 36

10

the BLM intends to remove all wild horses from the Checkerboard portion of the HMA.

Consistent with 16 USC 1334, the BLM does not intend to return gathered horses to public land

solid block of the HMA.” Id. at 2. The 2014 gather and removal described below proposes to

fulfill the commitments in the consent decree.

3. BLM’s Proposed 2014 Gather

In order to comply with the consent decree and the Wild Horses Act, BLM began making

preparations for the proposed 2014 gather. First, BLM determined, based on horse population

census, that there were approximately 800 horses total from the three HMAs on checkerboard

lands that needed to be removed. See Foster Decl at ¶ 13. Next, BLM complied with NEPA by

determining that a categorical exclusion applied to the gather. BLM assembled a team of 11

professionals ranging from Wild Horse and Burro Specialists and Wildlife Biologist to

Rangeland Management Specialists and Resource Managers to consider potential environmental

impacts. See Ex. 3 (BLM’s Categorical Exclusion). The team studied the proposed gather action

and reviewed the public comment received from BLM’s 2013 public scoping initiative. See Ex.

4 (Decision Record). BLM considered twelve established environmental criteria to determine if

this proposed action would potentially have a significant impact the environment. See Ex. 3, pg.

5-10 (identifying 12 extraordinary circumstances that could affect the environment such as

potential effects on natural resources, wilderness, or endangered species, among others). BLM

determined that “there are no extraordinary circumstances potentially having effects that may

significantly affect the environment,” id. at 1, and therefore concluded that a categorical

exclusion is appropriate for the gather. On July18, BLM issued a decision record to proceed

with the gather. Id.

IV. STANDARD OF REVIEW

A. Preliminary Injunction Standard

A preliminary injunction is an “extraordinary and drastic remedy, one that should not be

granted unless the movant, by a clear showing, carries the burden of persuasion.” Mazurek v.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 19 of 36

11

Armstrong, 520 U.S. 968, 972 (1997) (per curiam) (citation omitted) (emphasis in original).3 See

also GTE Corp. v. Williams, 731 F.2d 676, 678 (10th Cir. 1984) (“A preliminary injunction is an

extraordinary remedy; it is the exception rather than the rule.”) (citation omitted). As a result,

the Tenth Circuit has long required a movant to show a “clear and unequivocal” right to

injunctive relief. SCFC ILC, Inc. v. Visa USA, 936 F.2d 1096, 1098 (10th Cir. 1991). See also

Greater Yellowstone Coal. v. Flowers, 321 F.3d 1250, 1256 (10th Cir. 2003).

The party seeking preliminary relief must demonstrate: “(1) a likelihood of success on the

merits; (2) a likelihood that the movant will suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary

relief; (3) that the balance of equities tips in the movant’s favor; and (4) that the injunction is in

the public interest.” RoDa Drilling Co. v. Siegal, 552 F.3d 1203, 1208 (10th Cir. 2009) (citing

Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 555 U.S. 7, 19-20 (2008)). 4 If a plaintiff fails to meet its

burden on any of these four requirements, its request must be denied. See, e.g., Winter, 555 U.S.

at 20 (denying injunctive relief on the public interest and balance of harms requirements alone,

even assuming irreparable injury to protected species and a violation NEPA); Chem. Weapons

Working Grp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Army, 111 F.3d 1485, 1489 (10th Cir. 1997) (failure on the

balance of harms “obviat[ed]” the need to address the other requirements); Sprint Spectrum, L.P.

v. State Corp. Comm’n, 149 F.3d 1058, 1060 (10th Cir. 1998).

B. Judicial Review Under the Administrative Procedure Act

Because the Wild Horses Act and NEPA do not provide for a private right of action, the

Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), 5 U.S.C. §§ 701-706, provides for judicial review for

challenges to final agency actions under these statutes. See e.g., Utah v. Babbitt, 137 F.3d 1193,

1203 (10th Cir. 1998). Pursuant to Olenhouse, 42 F.3d at 1580, in the Tenth Circuit, “[r]eviews 3 In Mazurek, the Supreme Court noted that the movant’s “requirement for substantial proof is much higher” for a motion for a preliminary injunction than it is for a motion for summary judgment. Mazurek, 520 U.S. at 972.

4 The Tenth Circuit’s relaxed “serious questions” standard did not survive Winter, 555 U.S. at 22, which requires nothing less than a likelihood of success on the merits. Id. at 22 (stating that any lesser standards are “inconsistent with our characterization of injunctive relief”); RoDa Drilling Co., 552 F.3d at 1208-09.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 20 of 36

12

of agency action in the district courts [under the APA] must be processed as appeals.” Id.

(emphasis in original).

“The scope of review under the [APA] is narrow and a court is not to substitute its

judgment for that of the agency.” Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co.,

463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983). Under the “arbitrary and capricious” standard, administrative action is

upheld if the agency has “considered the relevant factors and articulated a rational connection

between the facts found and the choice made.” Baltimore Gas & Elec. Co. v. Natural Res. Def.

Council, 462 U.S. 87, 105 (1983) (citation omitted); Airport Neighbors Alliance v. United States,

90 F.3d 426, 429 (10th Cir. 1996). The court’s role is solely to determine whether “the decision

was based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of

judgment.” Citizens to Pres. Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 416 (1971)

“A presumption of validity attaches to the agency action and the burden of proof rests

with” the plaintiff. Morris v. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Comm’n, 598 F.3d 677, 691 (10th Cir.

2010) (quotations omitted). In deciding disputes that involve primarily issues of fact that

“‘require[] a high level of technical expertise,’ [the court] must defer to ‘the informed discretion

of the responsible federal agencies.’” Marsh v. Or. Natural Res. Council, 490 U.S. 360, 377

(1989) (quoting Kleppe v. Sierra Club, 427 U.S. 390, 412 (1976)); see also Baltimore Gas, 462

U.S. at 103 (“When examining this kind of scientific determination . . . a reviewing court must

generally be at its most deferential.”). “Deference to the agency is especially strong where the

challenged decisions involve technical or scientific matters within the agency’s area of

expertise.” Utah Envtl. Cong. v. Russell, 518 F.3d 817, 824 (10th Cir. 2008) (citing Marsh, 490

U.S. at 378). Thus, when dealing with the complex technical issues relating to application of the

Wild Horses Act and NEPA, a federal agency such as BLM “must have discretion to rely on the

reasonable opinions of its own qualified experts.” Marsh, 490 U.S. at 378.

V. ARGUMENT

A. Petitioners Will Not Succeed on the Merits

1. BLM Fully Complied with NEPA

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 21 of 36

13

CEQ’s NEPA regulations authorize agencies to use Categorical Exclusions for

“categor[ies] of actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the

human environment and which have been found to have no such effect in procedures adopted by

a Federal agency.” 40 C.F.R. §§ 1507.3(b)(2), 1508.4; see pp. 4-5 above. Where an agency

reasonably determines that a proposed action falls within a Categorical Exclusion and that there

are no extraordinary circumstances, no further NEPA analysis is required. Colorado Wild v. U.S.

Forest Serv., 435 F.3d 1204, 1209 (10th Cir. 2006) (“Under NEPA and CEQ regulations, if an

action falls within a particular [categorical exclusion], the agency need prepare neither an

[Environmental Impact Statement] nor an [Environmental Assessment].”). In this case,

Petitioners assume that an Environmental Impact Statement (“EIS”) or an Environment

Assessment (“EA”) was required as part of the gather review process. Pl. Br. at 1, 14-17.

Petitioners are mistaken.

a. BLM’s Evaluation of Environmental Significance was Appropriate

When considering a proposed action under a categorical exclusion, an agency is required

to determine whether there are extraordinary circumstances that would cause the action to have a

significant environmental effect. 43 C.F.R. § 46.205(c); 40 C.F.R. § 1508.4. BLM properly did

so here by considering whether any of the twelve (12) extraordinary circumstances identified in

the agency’s NEPA implementation procedures at 43 C.F.R. § 46.215 would occur as a result of

the gather. BLM considered, among other things, whether the gather would result in significant

impacts on natural and cultural resources, drinking water aquifers, threatened or endangered

species, or other ecologically significant or critical areas. See Ex. 3. In making this

determination, BLM relied on a team of 11 separate specialists and resource managers including

a Wild Horse and Burro Specialist, a Rangeland Management Specialist, a Wildlife Biologist, a

Botanist, an Archeologist, a Riparian Specialist, and various field managers. See id., at 10.

BLM’s professionals concluded that:

There are no unique or unknown risks associated with this removal of wild horses from the checkerboard land. The checkerboard land is within HMAs and has been managed for wild horses, including gather operations

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 22 of 36

14

for decades. The effects of gather operations on wild horses are well understood and this removal is not expected to create highly uncertain environmental effects.

* * *

No significant impacts to any resources are expected from this removal, including to any unique geographic characteristics. No such unique geographic characteristics or ecologically significant or critical areas are located within the checkerboard.

Id. at 6-10. BLM’s professionals also observed that “[t]his removal is not expected to create

significant environmental impacts to any resource.” Id. at 7; see also id. at 6, 8, 9. Given these

findings, BLM’s Field Managers concluded in their Decision Record that “the categorical

exclusion is appropriate in this situation because there are no extraordinary circumstances

potentially having effects that may significantly affect the environment.” See Ex. 4, at 1. This

determination is entitled to deference. See Citizens’ Comm., 297 F.3d at 1023 (referencing the

Fourth, Fifth, Seventh and Ninth Circuits finding that “[w]hen reviewing an agency’s

interpretation and application of its categorical exclusion under the arbitrary and capricious

standard, courts are deferential”); Town of Superior v. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Serv., 913 F. Supp.

2d 1087, 1100-01 (D. Colo. 2012) (finding that the APA “scope of this review is narrow” and

that “[a] presumption of validity attaches to agency action”).

b. BLM was not required to prepare an Environmental Assessment

Petitioners assert that BLM’s Categorical Exclusion review was improper and that BLM

“was required to prepare an EA [or EIS] before authorizing” the gather. Pl. Br. at 17.

Petitioners, however, have offered no cognizable legal or factual support for this proposition.

Petitioners merely cite two self-serving affidavits from photographers who assert that horse

“bands” or “families” will be “negatively affected” by the gather. Pl. Br. at 15. As an initial

matter, these declarations should be stricken as improper under Federal Rule of Evidence 701

because the testimony contains improper lay opinions and, under Federal Rule of Evidence 702,

Petitioners have not carried their burden of establishing the declarants’ qualifications to

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 23 of 36

15

competently testify on the expert subject matter offered. See Lust v. Merrell Dow Pharms., 89

F.3d 594, 598 (9th Cir. 1996). In any event, as set forth in the declaration of Kimberlee D.

Foster, BLM has been conducting gathers for decades and has observed that horses form new

bands once a gather concludes. See Foster Decl. ¶ 15. BLM’s declarant is the Manager of

BLM’s Rock Springs Field Office and, as an official congressionally delegated expert agency,

she is indisputably qualified to provide testimony on this issue. Simply, Petitioners have

provided no basis for their contention that an EA or EIS was required as a result of an

unsubstantiated allegation that the gather would somehow be disruptive to a particular “band” of

horses.

Petitioners also baldly allege that the gather “will inevitably affect myriad natural

resources in these HMAs.” Pl. Br. at 15. But Petitioners fail to provide any evidence as to how

these resources could be negatively impacted by the gather. More importantly, Petitioners ignore

that BLM considered the potential impacts to natural resources in its review of the extraordinary

circumstances factors in the categorical exclusion as described above. That is all that NEPA

requires. See Utah Envtl. Cong., 518 F.3d at 821 (“NEPA dictates the process by which federal

agencies must examine environmental impacts, but does not impose substantive limits on agency

conduct”) (citation omitted); Citizens Comm. to Save Our Canyons, 297 F.3d at 1023 (“Under

regulations promulgated by [CEQ], an agency is not required to prepare either an EIS or EA if

the proposed action does not ‘individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human

environment.”) quoting 40 C.F.R. § 1508.4. Petitioners have presented no basis for finding that

BLM failed to adequately conduct its NEPA review or why an EIS or EA would be required for

this action.5 Accordingly, Petitioners cannot meet their burden of proof and cannot show a

likelihood of success on the merits.

5 Throughout Petitioners’ brief, they confuse the provision in the consent decree obligating BLM to conduct scoping on proposed alternatives to the RMPs, with the distinct obligation to remove wild horses from RSGA’s Checkerboard lands. Pl. Br. at 7-9, 23. These two obligations are independent from one another, and BLM’s commitment to scope possible alternatives under NEPA does not alter the existing RMPs or AMLs. RSGA, ECF 92 at 21 (“The AMLs for the

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 24 of 36

16

c. BLM did not depart from its own guidance, nor did it depart from past practice

Having provided no substantive basis for setting aside the gather decision, Petitioners

next allege a series of procedural defalcations which are nothing more than red herrings. First,

Petitioners assert that BLM Manual § 4720.2.21 required preparation of an EA for the gather. Pl.

Br. at 15-16. Not so. BLM Manual § 4720.2.21 is inapplicable as that section relates to the

removal of excess horses under Section 3 of the Wild Horses Act. As detailed in the Decision

Record and above, the gather in this case was undertaken pursuant to Section 4 of the Wild

Horses Act. Further, the Manual language quoted by Petitioners states only that an “appropriate

NEPA analysis” is necessary. See BLM Manual § 4720.2.21(6) (Petitioners’ Ex. B). Because

BLM has demonstrated (see above) that its use of the Categorical Exclusion complied with

NEPA, Petitioners’ claim fails.6

Second, Petitioners are also incorrect in asserting that BLM “invariably prepare[s] at least

an EA for all wild horse roundups of any size” and that BLM’s reliance on a categorical

exclusion impermissibly deviated from past practice. Pl. Br. at 16 (emphasis in original) and n 2.

HMAs are established in the Green River RMP and no party has identified how, if at all, these AMLs are changed by the Consent Decree.”). Nor does BLM rely on the consent decree’s scoping provision to comply with NEPA in this case. As explained above, BLM complied with NEPA with the 2014 categorical exclusion, and just as Judge Kerr recognized in the previous litigation, in order to fulfill the mandate in Section 4 of the Wild Horses Act, there is a distinction between Checkerboard lands and the management of surrounding solid-block public lands under the RMPs. That is, RSGA’s Section 4 legal rights extend only to Checkerboard lands, whereas BLM must manage its lands under Section 3 and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (“FLPMA”) on the surrounding solid-block public lands.

6 Even if BLM did depart from its own guidance (which it did not) it would not render the categorical exclusion inapplicable. See Christensen v. Harris Cnty., 529 U.S. 576, 587 (2000) (referring to interpretations contained in policy statements, agency manuals, and enforcement guidelines as lacking the force of law).

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 25 of 36

17

Included as an exhibit with this filing is a categorical exclusion for a recent BLM gather. See Ex.

5 (DOI-BLM-UT-C010-2014-0037-CX). This document makes clear that BLM does rely on

categorical exclusions for gathers when it is appropriate to do so. However, even if BLM had

deviated from past practice, there is no legal justification for an injunction on that basis as

Petitioners would still be required to sustain their burden of showing that the Decision Record

was arbitrary and capricious. See FCC v. Fox Television Stations, 556 U.S. 502, 514 (2009)

(The APA standard of review is not more searching where the agency's decision is a change from

prior policy.).

Third, Petitioners allege that BLM violated NEPA by “entirely failing to engage the

public in the decision-making process.” Pl. Br. at 2 n.4. Petitioners fail to recognize that there is

no public comment requirement when an agency invokes a categorical exclusion. Nonetheless,

as a practical matter, BLM did ask for and accept comments well in advance of the gather. In

December 2013, BLM issued a scoping notice for a potential EA for a Great Divide Basin HMA

gather on Checkerboard lands that was considered for this summer. See

http://www.blm.gov/wy/st/en/info/news_room/2013/december/10rsfo-gather.html (last visited

Aug. 19, 2014). Four of the five Petitioners in this case provided comments. While BLM

ultimately determined to proceed in a different manner than envisioned by the scoping notice, the

Decision Record affirmatively states that BLM did consider the public comments received from

the scoping notice. See Ex. 4 at 2, 4. Thus, Petitioners did have an opportunity to comment prior

to the gather decision and their comments were duly considered.

Lastly, Petitioners assert that the Categorical Exclusion is inapplicable because the gather

is not limited to private lands and because the gathered horses will be removed permanently. Pl.

Br. at 17. As for the latter contention, BLM has already made clear that there is no legal

requirement to return gathered horses to the range as Petitioners allege. See p. 20 n.2, below.

With respect to the applicability of the categorical exclusion, BLM does not dispute that

516 DM 11.9 D(4) refers to the removal of horses from private lands. Still, BLM is wholly

within its authority to gather horses from the Checkerboard under that provision. The Tenth

Circuit has unequivocally stated that “[o]nce an agency establishes categorical exclusions, its

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 26 of 36

18

decision to classify a proposed action as falling within a particular categorical exclusion will be

set aside only if a court determines that the decision was arbitrary and capricious.” Citizens’

Comm. to Save Our Canyons v. U.S. Forest Serv., 297 F.3d 1012, 1023 (10th Cir. 2002); id.

(referencing the Fourth, Fifth, Seventh and Ninth Circuits finding that “[w]hen reviewing an

agency’s interpretation and application of its categorical exclusion under the arbitrary and

capricious standard, courts are deferential”); see also Long Island Care at Home, Ltd. v. Coke,

551 U.S. 158, 171 (2007) (“[A]n agency’s interpretation of its own regulation is controlling

unless plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulations being interpreted.”) (internal

quotation marks and citations omitted), Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452, 461 (1997).

It has been well-established herein that BLM was compelled to remove these horses from

the Checkerboard pursuant to the Wild Horses Act and the consent decree. See pp. 6-10, above.

Further, this Court has recognized that the Checkerboard land pattern presents unique challenges

to land management. See RSGA, 935 F. Supp. 2d at 1187-88. Indeed, BLM’s Decision Record

found that:

due to the unique pattern of land ownership, and as recognized by the Consent Decree, it is practicably infeasible for BLM to meet its obligations under Section 4 of the [Wild Horses Act] while removing wild horses solely from the private lands sections of the checkerboard.

See Ex. 4 at 4. As stated in the attached declaration of Kimberlee D. Foster, BLM’s Field Office

Manager, the lack of boundary fencing coupled with the Checkerboard pattern make it infeasible

to conduct a removal of wild horses only from the private land sections. See Foster Decl. ¶¶ 10-

11. Ms. Foster also confirmed that wild horses travel freely back and forth between public and

private sections, which make removal from only private land sections untenable. Id.; American

Horse Protection Assoc. v. Andrus, 460 F. Supp. 880, 885 (D. Nev. 1978) (“The only practical

way this mandate [under Section 4] can be honored in an unfenced checkerboard area is by

removal of all the horses.”), rev’d in part on other grounds, 608 F.2d 811 (9th Cir. 1979).

Given BLM’s legal obligations to remove the horses and the practical limitations on

removing horses from private lands, BLM’s reliance on 516 DM 11.9 D(4) was wholly

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 27 of 36

19

reasonable and Petitioners cannot credibly assert that BLM failed in its duty to “articulate a

rational connection between the facts found and the decision made.” See High Country Citizens’

Alliance v. U.S. Forest Serv., 203 F.3d 835, at *4 (10th Cir. 2000) (Court need only “ascertain

whether the agency examined all the relevant data and articulated a rational connection between

the facts found and the decision made”), quoting Olenhouse, 42 F.3d at 1574; Wild Earth

Guardians v. U.S. Forest Serv., 668 F. Supp. 2d 1314, 1333 (D.N.M. 2009) (it is the Court’s role

to determine whether the [Categorical Exclusions] were supported by reasonable facts and

conclusions.); see also Sierra Club v. Bostick, NO. VIV-12-742-R, 2013 WL 6858685, at *10

(W.D. Okla. Dec. 30, 2013) (NEPA does not require the government to do the impractical.).

In sum, BLM properly considered the applicability of a Categorical Exclusion and

undertook an appropriate review to determine whether the gather would result in extraordinary

circumstances that could cause significant environmental harm. Petitioners’ arguments to the

contrary reflect nothing more than dissatisfaction with the choices made. That dissatisfaction is

insufficient to meet Petitioners’ high burden of proof and, therefore, Petitioners cannot show a

likelihood of success on the merits of their NEPA claim.

2. BLM Complied with the Wild Horses Act

Petitioners contend that BLM must make an “excess” determination under Section 3 of

the Wild Horses Act before removing any wild horses from the Checkerboard, and must limit

any removal so that the population does not drop “below low AML in the Adobe Town and

Great Divide Basin HMAs . . . .” Pl. Br. at 18-19. Petitioners’ argument ignores Section 4 of the

Wild Horses Act.

Under 16 U.S.C. § 1334, if BLM receives a request to remove wild horses from private

lands, it “shall arrange to have the animals removed.” Id. Although BLM can exercise

discretion as to how and when it removes these wild horses, the duty to ultimately remove these

animals is non-discretionary. 43 C.F.R. § 4720.2-1. This mandatory duty becomes particularly

important in the Checkerboard because it harmonizes a number of different competing statutory

obligations and controlling case law.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 28 of 36

20

The Supreme Court in Leo Sheep recognized that the government did not reserve an

implied property interest, like an easement, under the Pacific Railroad Act when it created the

Checkerboard. In Camfield the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Unlawful

Inclosures Act, which effectively prevents RSGA from fencing wild horses out from its property.

At the same time, RSGA cannot be compensated for any damage that occurs from wild horses

grazing on its land. Mountain States Legal Found. v. Hodel, 799 F.2d 1423, 1431 (10th Cir.

1986). Thus, RSGA is left with an acknowledged property interest in its private lands, but it

cannot prevent or be compensated for wild horses crossing and grazing on its lands. The

available remedy that harmonizes all of these competing mandates is Section 4 of the Wild

Horses Act. 16 U.S.C. § 1334. That is, upon request BLM will remove wild horses thereby

protecting RSGA’s interest to the extent allowable under controlling law.7 Id. The fact that

some public lands are involved in the gather does not change this statutory mandate.

As Petitioners so definitively demonstrated in the previous litigation, there is no practical

ability to segregate wild horses that reside on private lands from those that reside on public lands

within the Checkerboard at any one point in time. RSGA, ECF 86-1 at 7-8; see also Ex. 4 at 3-4

(“[I]t is practicably infeasible for the BLM to meet its obligations under Section 4 of the WHA

while removing wild horses solely from the private lands sections of the checkerboard.”). Yet

even with this acknowledgement, Petitioners still insist that BLM must operate solely under

7 Petitioners suggest, without any meaningful citation to authority, that BLM must return any wild horses that it removes from private land to neighboring public lands. Pl. Br. at 1, 16. This is legally incorrect. There is nothing in the statute or regulations that require BLM to return removed horses to public land. The only limitation on BLM’s removal authority is that it cannot destroy a wild horse without approval from an authorized officer. 43 C.F.R. § 4730.1. From a practical standpoint, Petitioners’ academic theory makes even less sense, especially on the Checkerboard. Petitioners would have BLM remove wild horses from RSGA’s land, but then require it to return these horses to the neighboring public land parcel. This exercise in futility would ensure only one thing – a perpetual request from RSGA to continually remove wild horses that drift back onto their lands. Obviously, Congress did not envision such a scenario, and correctly did not place any limitation on BLM’s Section 4 removal authority.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 29 of 36

21

Section 3 and can only remove those horses that it determines are “excess” above AML. This

presents an impossible situation. If BLM removes only “excess” horses from the Checkerboard,

by definition that will leave remaining horses on RSGA’s lands contrary to the mandate in

Section 4 and BLM’s commitment in the consent decree. 16 U.S.C. § 1333; see also Ex. 2

(RSGA notifying BLM of non-compliance when gather only removed excess horses).

Petitioners are effectively asking this Court to: (1) entirely ignore Section 4; and (2) create, under

the auspices of Section 3, an implied reservation on RSGA’s lands just because they neighbor

federal land. Neither proposition is reasonable.

No implied interest can be divined from Section 3 and Petitioners’ position runs contrary

to Leo Sheep. Indeed, this Court already wrestled with this very issue and found that it must

recognize RSGA’s ability to exercise its rights under Section 4. RSGA, 935 F. Supp. 2d at 1188

(“The BLM is statutorily obligated to manage wild horses in this area consistent with RSGA’s

Section 4 legal rights notwithstanding the RMP herd management objectives for federal land, or

the particular management challenges presented.”).8 Here, BLM seeks only to discharge its

Section 4 duty and comply with the consent decree. Ex. 4 at 3 (“Through this gather, the BLM is

not removing excess wild horses from the public lands under Section 3 of the WHA, 16 U.S.C. §

1333.”). This is consistent with this Court’s previous orders and permissible under the Wild

Horses Act. Petitioners have failed to demonstrate a likelihood of success on this claim.

B. Petitioners Fail to Demonstrate The Likelihood of Any Irreparable Harm

8 Petitioners’ reliance on Colorado Wild Horse and Burro Coalition v. Salazar, 639 F. Supp. 2d 87 (D.D.C. 2009), is misplaced. The issue in that case did not involve a request by a landowner to remove wild horses under 16 U.S.C. § 1334, much less a consent decree. Rather, that case only involved BLM’s interpretation of Section 3, 16 U.S.C. § 1333. Id. at 97 (“[T]he Court rejects Defendants' proposed construction that § 1333(b) requires the removal of excess animals whereas § 1333(a) permits the removal of non-excess animals.”). The Court did not opine on Section 4, and limited its holding to just Section 3. Id. Moreover, as Petitioners concede, BLM does not propose to remove all of the horses from the HMAs. Pl. Br. at 19 (recognizing that BLM will leave remaining horses).

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 30 of 36

22

Petitioners cannot meet their heavy burden of demonstrating irreparable harm. “‘[A]

showing of probable irreparable harm is the single most important prerequisite for the issuance

of a preliminary injunction [and] the moving party must first demonstrate that such injury is

likely before the other requirements for the issuance of an injunction will be considered.’”

Dominion Video Satellite v. Echostar Satellite Corp., 356 F.3d 1256, 1260-61 (10th Cir. 2004)

(quoting Reuters Ltd. v. United Press Int’l, 903 F.2d 904, 907 (2d Cir. 1990)). Irreparable injury

for purposes of a preliminary injunction “must be both certain and great,” not “merely serious or

substantial.” Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians v. Pierce, 253 F.3d 1234, 1250 (10th Cir.

2001) (citations omitted); RoDa Drilling Co. v. Siegal, 552 F.3d 1203, 1210 (10th Cir. 2009)

("Purely speculative harm will not suffice, but rather, a plaintiff . . . [must] show a significant

risk of irreparable harm . . . to have satisfied his burden.").

As an initial matter, even if this Court were to find a likely violation of law, there is no

presumption of harm where, as here, the violation involves an environmental statute. Amoco

Prod. Co. v. Village of Gambell, 480 U.S. 531, 544-545 (1987) (reversing a preliminary

injunction premised on the presumption of irreparable damage when an agency fails to evaluate

thoroughly the environmental impact of a proposed action); Fund for Animals v. Lujan, 962 F.2d

1391, 1400 (9th Cir. 1992) (“Merely establishing a procedural violation . . . does not compel the

issuance of a preliminary injunction”) (citation omitted). In a unanimous decision, the Ninth

Circuit has reaffirmed that “irreparable harm” should not be presumed in environmental cases

and that alleged environmental injuries may in fact be outweighed by other considerations,

including the risks posed to other resource values. See Lands Council v. McNair, 537 F.3d 981,

1005 (9th Cir. 2008) (risks of catastrophic fire, insect infestation, and disease may outweigh

alleged harm to individual species). Here, Petitioners bear the burden of demonstrating that the

gather is likely to result in a concrete and actual injury to their interests that is “irreparable.”

Petitioners cannot make this showing. Moreover, as explained below, the alleged environmental

injuries are outweighed by considerations such as BLM’s obligations under the consent decree

and the impacts of halting the gather on RSGA.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 31 of 36

23

Petitioners profess that their “aesthetic, recreational, professional, and economic

interests,” will be harmed because the gather “will make the difficult task of finding any wild

horses in these HMAs…more difficult (and potentially impossible depending on which horses

are ultimately removed)”. Pl. Br. at 21. Petitioners, however, are not accurately depicting the

scope of the gather. The gather will only remove horses from the Checkerboard. As BLM is not

removing horses from non-Checkerboard lands, Petitioners will be able to continue viewing

horses on the overwhelming majority of these HMAs. Further, following the gather, up to 300

horses may reside on the Checkerboard within the Great Divide Basin and Salt Wells Creek

HMAs before BLM may be required to re-gather in those area. Thus, Petitioners can also

continue to view horses on the Checkerboard in those HMAs as well as in the White Mountain

HMA. See Foster Decl. ¶ 14.

As to Petitioners’ argument that it will be “more difficult” to view horses, even if this

rose to the level of irreparable harm, they have not established that this alleged difficulty will

occur on portions of the HMAs where they visit, nor have they established any legally

cognizable right to easily view horses on any specific area of an HMA or any specific horses.

While declarants Walker and Curyl state that they visit Checkerboard lands, they make no

attempt to distinguish the location of their horse-related activities between Checkerboard and

non-Checkerboard lands. Declarant Kathrens makes no specific mention of visiting

Checkerboard lands. Pl. Br. Exs. M-O. Thus, they have not shown irreparable harm with respect

to this particular gather.

Petitioners next assert that Petitioners will be harmed as a result of horse bands being

separated by the gather. Pl. Br. at 15. BLM’s declarant however has made clear that “wild

horses within these HMAs have adapted and form new bands after a gather.” See Foster Decl. ¶

15. Thus, even if there was a recognizable band disruption, and even if that disruption somehow

in turn harms Petitioners, any such disruption would be temporary and therefore could not result

in harm that is irreparable. Petitioners also claim that the gather will affect their professional and

business interests. Pl. Br. at 21-22. They provide no specificity to these alleged harms which are

speculative at best. As this court has held, “vague assertions about [ ] monetary harm are clearly

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 32 of 36

24

insufficient to establish irreparable harm.” Cody Labs. v. Sebelius, NO. 10-CV-147-ABJ11,

2010 WL 3119279, at *17 (D. Wyo. July 26, 2010).

Petitioners’ alleged irreparable harms boil down to an assertion that they will no longer

be able to view horses on the range for various purposes after the gather. Pl. Br. at 21-22. BLM

has shown, however, that:

After the removal of the wild horses from the Checkerboard lands, there will continue to be wild horse populations on the BLM administered lands within these three HMAs. The BLM-administered land within these HMAs, but outside the Checkerboard, has unrestricted public access and ample viewing and photographic opportunities, particularly in areas where the wild horses tend to congregate near water sources. For example, within the BLM-administered land sections (north of the Checkerboard lands) of the Great Divide Basin HMA, wild horses are often present at the Black Rock Well Development, the Hay/Brannon Reservoir Complex, and the Alkali Basin and Reservoir. Additionally, the Salt Wells Creek HMA contains the Alkali Creek, Vermillion Creek and the Chicken Creek/Chicken Springs Basin that are frequented by wild horses and are located on BLM-administered land south of the Checkerboard lands. In addition to the viewing opportunities for wild horses within these HMAs, both the Little Mountain and White Mountain HMAs have an abundance of public viewing access areas within the RSFO area, including the popular Wild Horse Loop Tour Road running through the White Mountain HMA.…

See Foster Decl. ¶ 14. BLM’s declaration leaves no doubt that there will continue to be ample

opportunities for Petitioners to view horses in the wild in these HMAs (and on the Checkerboard

for that matter given RSGA’s agreement to maintain a sizeable population thereon). Given that

they can continue their activities with respect to horse viewing in each of these three HMAs,

Petitioners cannot establish that their asserted harm is either “certain and great.” See Prairie

Band of Potawatomi Indians, 253 F.3d at 1250. Accordingly, Petitioners’ claims of irreparable

harm should be rejected.

C. The Balance of the Equities Favor Allowing the 2014 Gather to Proceed

Petitioners must also show that the balance of the equities and public interest favor an

injunction. Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008). They have failed to

make the requisite showing.

Case 2:14-cv-00152-NDF Document 30 Filed 08/20/14 Page 33 of 36

25

Checkerboard land management demands collaboration between public and private land

ownership. For decades, RSGA and BLM have worked together to manage this complicated

land pattern. Although there have been disputes, the consent decree furthers this working

relationship and benefits the public, including Petitioners, because it allows BLM to maintain

wild horses on RSGA’s lands when it would not otherwise be able to do so. RSGA, 935 F. Supp.

2d at 1188. Allowing wild horses to remain on these lands furthers the public interest. Id. at

1192.

Moreover, compliance with a consent decree, entered as an order of this Court,

undoubtedly serves the public interest. Even if Petitioners could establish the other factors, with

these considerations the equities tip sharply in BLM’s favor. In Defense of Animals v. Salazar,

675 F. Supp. 2d 89, 98 (D.D.C. 2009) (finding the need for a gather outweighs declarants’ desire

to observe and study wild horses on the range: “That injury—assuming for the sake of argument

that it is irreparable—must be weighed against the substantial harm to other interests that likely

would result if the Court were to enjoin the proposed gather”); Habitat for Horses v. Salazar,

745 F. Supp. 2d 438, 458 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) (“The public interest is served by implementing the