WWII History - June 2013

-

date post

02-Feb-2016 -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

2

Transcript of WWII History - June 2013

WW

II HISTORY■

JUNE 2013 V

olume 12, N

o. 4

0 74470 02360 9

0 6

$5.99US $6.99CAN

RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 8

JUNE 2013

Cur

tis 0

2360

www.wwiihistorymagazine.com

AMERICAN GLIDERS, BRITISH GENERAL AUCHINLECK,THE GI’S K-RATION, BOOK & GAME REVIEWS, AND MORE!

RUSSIAN FRONT

German GarrisonAnnihilatedTAKING HILL 400

U.S. Rangers vs. Fallschirmjägersin the Hürtgen Forest

RAID ON CLARK FIELD

Destroying KamikazesOn the GroundVALIANT MERCHANT CRUISERS Battling German Raiders

+

W-Jun13 C-1_W-May05 C-1 Wholesale 4/3/13 3:13 PM Page C3

W-Well Go FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/5/13 2:26 PM Page 2

W-Wargaming FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:59 PM Page 2

WWII History (ISSN 1539-5456) is published seven times yearly by SovereignMedia, 6731 Whittier Ave., Suite A-100, McLean, VA 22101. (703) 964-0361.Periodical postage paid at McLean, VA, and additional mailing offices. WWIIHistory, Volume 12, Number 4 © 2013 by Sovereign Media Company, Inc., allrights reserved. Copyrights to stories and illustrations are the property of theircreators. The contents of this publication may not be reproduced in whole orin part without consent of the copyright owner. Subscription services, backissues, and information: (800) 219-1187 or write to WWII History Circula-tion, WWII History, P.O. Box 1644, Williamsport, PA 17703. Single copies:$5.99, plus $3 for postage. Yearly subscription in U.S.A.: $24.99; Canada andOverseas: $40.99 (U.S.). Editorial Office: Send editorial mail to WWII Histo-ry, 6731 Whittier Ave., Suite A-100, McLean, VA 22101. WWII History wel-comes editorial submissions but assumes no responsibility for the loss or dam-age of unsolicited material. Material to be returned should be accompanied bya self-addressed, stamped envelope. We suggest that you send a self-addressed,stamped envelope for a copy of our author’s guidelines. POSTMASTER: Sendaddress changes to WWII History, P.O. Box 1644, Williamsport, PA 17703.

WWII HISTORY

4 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Contents

Features30 “Passchendaele with Tree Bursts”

The U.S. 2nd Ranger Battalion held Hill 400 in the embattled Hürtgen Forest against five fierce German counterattacks in December 1944.By James I. Marino

38 Getting the Gliders Off the GroundThe American glider-building program more often resembled a comedy of errors thana serious wartime manufacturing effort.By Flint Whitlock

44 Death of a GarrisonThe German forces defending the city of Ternopil were virtually annihilated by the RedArmy in the autumn of 1943.By Pat McTaggart

56 Gallantry on the High SeasThe heroics of British Royal Navy armed merchant cruisers Rawalpindi and Jervis Baywere indicative of the courage displayed by the little vessels defending the convoys.By Robert Barr Smith

66 Kamikazes Caught on the GroundIn January 1945, planes of the U.S. Fifth Air Force smashed Japanese kamikazes at Clark Field in Philippines before they could attack U.S. Navy ships.By Robert F. McEniry, Lt. Col. USAF (Ret.)

0 74470 02360 9

0 6$5.99US $6.99CAN

RETAILER: DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 8

JUNE 2013

Cur

tis 0

2360

www.wwiihistorymagazine.com

AMERICAN GLIDERS, BRITISH GENERAL AUCHINLECK,THE GI’S K-RATION, BOOK & GAME REVIEWS, AND MORE!

RUSSIAN FRONT

German GarrisonAnnihilatedTAKING HILL 400

U.S. Rangers vs. Fallschirmjägersin the Hürtgen Forest

RAID ON CLARK FIELD

Destroying KamikazesOn the GroundVALIANT MERCHANT CRUISERS Battling German Raiders

+

Columns06 EditorialDiscovery in the depths of Lake Garda.

08 InsightCombat fatigue took its toll on the fightingmen of World War II.

12 Top SecretAllied intelligence personnel, including Americans, at secret locations in Britainhelped win the war against Nazi Germanyand Imperial Japan.

18 OrdnanceThe K Ration fed millions of American troopsand refugees during World War II.

24 ProfilesPrior to his arrival in North Africa, GeneralSir Claude Auchinleck primarily led Indiantroops and performed well in difficult circum-stances during the campaign in Norway.

68 BooksPrior to Pearl Harbor, a concerted effort wasmounted to keep the United States out of WorldWar II.

76 Simulation GamingIt might be time to step back from the zombiecraze and go in a new direction.

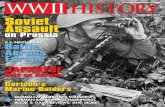

Cover: German infantry-men move cautiously alonga trench during the bitterfighting on the RussianFront. Story page 44.Photo: Bundesarchiv Bild101I-708-0256-15A;Photo: Scheerer

June 2013

W-Jun13 TOC-cg_W-Jul06 TOC 4 4/3/13 3:24 PM Page 4

W-Magnolia FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:59 PM Page 2

6 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

WWII HISTORYVolume 12 ■ Number 4

CARL A. GNAM, JR.Editorial Director, Founder

MICHAEL E. HASKEWEditor

LAURA CLEVELANDManaging Editor

SAMANTHA DETULLEOArt Director

CONTRIBUTORS:Richard A. Beranty, Jon Diamond, Hervie

Haufler, Al Hemingway, Joseph Luster,

James I. Marino, Robert F. McEniry,

Pat McTaggart, Duane Schultz,

Robert Barr Smith, Flint Whitlock

ADVERTISING OFFICE:BEN BOYLES

Advertising Manager

(570) 322-7848, ext. 110

MARK HINTZChief Executive Officer

KEN FORNWALTData Processing Director

JANINE MILLERSubscription Customer Service

(570) 322-7848, ext. 164

CURTIS CIRCULATION COMPANYWORLDWIDE DISTRIBUTION

SOVEREIGN MEDIA COMPANY, INC.6731 Whittier Avenue, Suite A-100

McLean, VA 22101-4554

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER SERVICE AND BUSINESS OFFICE:

1000 Commerce Park Drive, Suite 300

Williamsport, PA 17701

(800) 219-1187

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

Editor ialDiscovery in the depths of LakeGarda.SIXTY-SEVEN YEARS AFTER IT SANK IN THE DEPTHS OF LAKE GARD A INnortheastern Italy on the stormy night of April 30, 1945, an American amphibious vehicle, a 2.5-ton DUKW, has likely been located sitting upright in 905 feet of water.

The finding, intriguing to those following the stories of World War II relics discovered, recov-ered, and possibly restored decades after they were lost, may also finally bring some closure tothe families of 24 soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division who drowned in the lake and went downwith the DUKW that night. These men died just a week before the end of the war in Europe onMay 8, 1945, and only about 48 hours before all German forces in Italy surrendered to the Allieson May 2. Tragically, there were casualties right up to the hour that the guns fell silent.

During the closing offensive of the war in Italy, the 10th Mountain Division had been amongthe Allied units chasing the remnants of the beaten German Army northward toward the Alps,the Brenner Pass, and the Austrian frontier. Lake Garda, 60 miles east of Milan, was near the villa

occupied by deposed dictator Benito Mussolini,who had recently proclaimed the Fascist ItalianSocialist Republic, a mostly fictitious state, moreform than substance.

On that fateful night, the DUKW, which rou-tinely had room for 12 men, was loaded with25 soldiers. One report claims these were troopsof the 85th Infantry Regiment, members ofCompany K, and a machine-gun platoon ofCompany M. Another says that the troops werefrom the 605th Field Artillery Battalion with adriver from the Quartermaster Corps. An Ital-ian account relates that a small artillery piecewas also aboard. Soon after the craft set outacross the lake, it foundered, dumping its humancargo into the water.

Although the fog of war and the passage oftime have given rise to confusion in identifyingthe unit to which the casualties belonged, a sin-gle soldier, reportedly identified as CorporalJohn Hough, survived by clinging to a floatingvehicle part. The other 24 men, ages 18 to 25,

were officially listed as missing in action. The reason for overloading the amphibious vehicle isalso apparently lost to history.

Mario Fusato, leader of the archaeological team that discovered the DUKW resting at the bot-tom of Lake Garda, told the Christian Science Monitor, “It was the biggest disaster to happen inmodern times on Lake Garda.” In a subsequent interview with Ansa, an Italian news agency,Fusato said, “On Sunday, the sonar gave us an initial image, but it wasn’t clear enough to be ableto say for sure that it was the DUKW. On Monday, though, we used a remote-controlled cameraand we saw it. It is intact and sitting upright. There are lots of objects around it, which could bethe skeletons or remains of the soldiers who drowned.”

The wreck site lies too deep for divers. Fishing nets have become entangled around the vehicle,and tethered search equipment could easily snag at great depth. Any attempts to recover artifactsor determine the presence or absence of human remains will be challenging. Further, a decisionwill have to be made as to whether the site is designated as a war grave and treated as a sunkenship would be or if a salvage operation should be conducted with any remains recovered and iden-tified subsequently returned to family members for burial.

The searchers who located the sunken DUKW have notified American authorities, and ulti-mately it will be the U.S. government that decides what, if anything, will be done in the future.

Michael E. Haskew

An American DUKW

W-Jun13 Editorial_W-Jul06 Letters 4/3/13 5:15 PM Page 6

W-Bradford FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 6:00 PM Page 2

THE JAPANESE OPENED UP WITH HEAVY MORTAR FIRE JUST AS THE MARINESmoved off the beach and started inland. The men hit the deck and took any cover they could findas the barrage of shells exploded around them. They were completely pinned down.The shells fell faster and faster until they sounded like one continuous raging roar.For long agonizing minutes, no one could move. It was September 15, 1944, on atiny spit of land called Peleliu.

Eugene Sledge, a 21-year-old private, never forgot his first day in combat. Hedescribed it 35 years later in his classic book With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Oki-nawa. “I thought it would never stop,” he wrote about the barrage that day. “I wasterrified by the big shells arching down all around us. One was bound to fall directlyinto my hole. I thought it was as though I was out there on the battlefield all bymyself, utterly forlorn and helpless…. My teeth ground against each other, my heartpounded, my mouth dried, my eyes narrowed, sweat poured over me, my breath

I By Duane Schultz I

The Breaking PointCombat fatigue took its toll on the fighting men during World War II.

came in short irregular gasps, and I was afraidto swallow lest I choke.”

He survived that day and the days that fol-lowed, but as the battle for Peleliu wore on,Sledge found that during every prolongedshelling “I often had to restrain myself and fightback a wild, inexorable urge to scream, to sob,and to cry. As Peleliu dragged on, I feared thatif I ever lost control of myself under shell fire,my mind would be shattered.”

Yet, despite the horrors and the fearsomememories that haunted him for decades, Sledgewas among the fortunate ones. He came per-ilously close to the breaking point in combat butnever quite reached it. He never completely lostcontrol; he did not drop his weapon or try toclaw his way deep into the earth with his finger-nails, or run screaming and panic stricken to therear. He never reached the point that he couldnot take any more, as thousands of men do inevery war, for as long as there have been wars.

The number of combat fatigue cases in Amer-ican fighting units in World War II was stag-gering. More than 504,000 troops were lostdue to “psychiatric collapse,” an early term forreaching the breaking point. That was theequivalent of nearly 50 infantry divisions lost tothe war effort. Far more men were renderedunfit for combat in World War II than in anyprevious war, primarily because the battles werelonger and more sustained.

Some 40 percent of all the medical dischargesin World War II were for psychiatric reasons, theso-called “Section 8s.” In one survey of combatveterans in the European Theater of Operations,fully 65 percent admitted to having at least oneepisode during combat in which they felt inca-pacitated and unable to perform because ofextreme fear. One out of every four casualties inWorld War II was attributed to combat fatigue,with more cases reported in the Pacific than inEurope. On Okinawa alone, 26,000 psychiatriccasualties were documented. Overall, 1,393,000soldiers, sailors, and airmen were treated forcombat fatigue in World War II.

Historian John C. McManus described whatcombat fatigue is like. A soldier“starts trembling so bad he can’thold his rifle. He doesn’t want toshake but he does, and that solveshis problem. Involuntarily, hebecomes physically incapable. Hejust plain ‘gives up.’” It wasreported that an infantryman inNorth Africa “went crazy andbeat his head against our foxholetill his skin on his forehead was

Artist Tom Lea’s iconicpainting The 2,000 YardStare illustrates the toll

that combat may take onthe psyche of an individual.Although its manifestationsvaried from one individualto another, shell shock, orcombat fatigue, was bound

to affect any soldier tosome extent.

8 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

InsightU.S. Army Center for Military History, Army Art Collection

W-Jun13 Insight_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:24 PM Page 8

W-Victory Art_Layout 1 4/5/13 11:41 AM Page 2

just hanging in strands. He was foaming at themouth just like a madman.” At Anzio, a sergeantwho had been in combat for almost a yearstarted running so fast he had to be tackled andphysically restrained. A friend said, “He was thelast person in the world you would have thoughtthat would happen to.” Soldiers soon learnedthat it could happen to any of them.

One truism about the stress of continuouscombat is that every soldier, no matter how welltrained or how experienced, has a breakingpoint. “There is no such thing as ‘getting used tocombat,’” wrote a group of psychiatrists in a1946 report titled Combat Exhaustion. “Eachmoment of combat imposes a strain so great thatmen will break down in direct relation to theintensity and duration of their exposure.”

In some situations, such as the fierce and sus-tained fighting on the beaches and in thehedgerows of Normandy, fully 98 percent ofthose who were still alive after 60 days of fight-ing became psychiatric casualties. In less sus-tained fighting, the breaking point is typicallyreached between 200 and 240 days on the line.In the British Army in Europe, it was found thata rifleman could last for about 400 days, butthat was attributed to the fact that the Britishrelieved their troops for four days of rest every12 to 14 days. American troops remained inbattle continuously with no relief for as long as80 days at a time.

The 1946 Combat Exhaustion report con-cluded, “Psychiatric casualties are as inevitableas gunshot and shrapnel wounds…. The gen-eral consensus was that a man reached his peakof effectiveness in the first 90 days of combat,and that after that his efficiency began to falloff, and that he became steadily less valuablethereafter, until he was completely useless.”

The experience of reaching the breakingpoint was given different names in differentwars. During the Civil War it was sometimesreferred to as “nostalgia” because peoplethought it was caused by homesickness ratherthan the experiences of battle. Another nameapplied at that time was “irritable heart,” alsoknown as “Da Costa’s Syndrome,” after theU.S. Army surgeon, Dr. Jacob Mendes DaCosta. He described the symptoms as shortnessof breath, discomfort in the chest, and palpita-tions, all of which he believed were caused bythe stress of combat. By World War I, the con-dition had become known as “shell shock.”

As long as there have been wars, regardlessof the style of combat or the killing power ofthe weapons, extreme fear to the point of panicand loss of control, exhaustion, numbness, andsheer terror have caused men to collapse, trem-ble, and run screaming from the field of battle.

World War II, with its far more powerfulweapons of destruction, was no exception.

In 1943, the American Psychiatric Associa-tion described what it called the “GuadalcanalDisorder” that appeared during the deadly, pro-longed, close-quarters combat in capturing theisland of Guadalcanal in the Solomons. Thiswas America’s first large-scale offensive opera-tion of the war.

More than 500 Marines were treated for anarray of symptoms including “sensitivity tosharp noises, periods of amnesia, tendency toget panicky, tense muscles, tremors, hands thatshook when they tried to do anything. Theywere frequently close to tears or very short-tem-pered.” When it was thus demonstrated thateven an elite force of Marines was susceptibleto such breakdowns, the situation became ofmajor concern to the War Department. If itcould affect the Marines in that manner, thenno troops could be considered exempt.

For the majority of troops, fear is ever-presentin combat, but it does not always lead to inca-pacitation. Sometimes fear can result in an arrayof symptoms that can temporarily disable a sol-dier without necessarily leading to a diagnosis ofcombat fatigue and a forced period of relief fromthe front line. These symptoms include a franticheart rate, uncontrollable trembling, sweating,and periods of weakness, vomiting, and invol-untary urination and defecation. The last twosymptoms are the most dreaded because they areso hard to conceal and cause such feelings asshame, embarrassment, and humiliation. Somesoldiers consider them to be the most overt signsof cowardice to their comrades.

Sometimes the stress of combat is so over-

whelming that it leads to a collective panic inwhich whole units show signs of combatexhaustion and simply leave the battlefieldtogether. Charles MacDonald, a company com-mander in France, watched his entire companycollapse under a German attack. “They walkedslowly on toward the rear,” he wrote, “half-dazed expressions on their faces.”

Some react to the stress of combat by com-mitting suicide. One American soldier was soexhausted physically and emotionally duringthe Battle of the Bulge that he thought of killinghimself because he was convinced that hewould never make it out alive anyway. “I hadbeen living in such miserable, bitter cold, andscared at Bastogne, I didn’t really care whathappened. A click of the safety and tug of thetrigger and my suffering would be over.” Hehad to force himself to put on the safety catchon his rifle. “You see, I didn’t want to killmyself [but] I was afraid that I was going to doit on impulse. Suffering does things to you.”

A second extreme reaction to combat stressis a self-inflicted wound. Some men at thebreaking point shoot themselves in the hand orfoot. Lieutenant Paul Fussell, an infantry offi-cer, found that hundreds of soldiers in the Hürt-gen Forest fighting shot themselves to get out ofthe line. They usually chose the left hand orfoot. Fussell said, “For most boys being right-handed, the shooting had to be done with theright hand, working with a pistol, carbine, orrifle. The brighter soldiers used some cloth—an empty sandbag would do—to avoid telltalepowder burns near the bullet hole.”

So many men wounded themselves thatArmy hospitals had to set up special wards tohouse those soldiers designated as SIWs (self-inflicted wounds). When they recovered, mostwere tried and convicted of “carelessness withweapons” and given six-month sentences in thestockade.

Another way out for those who could notstand up to the stress of combat or who simplydid not like Army life anymore was to desert.This was a lot easier to do in Europe than onsome remote Pacific island. The U.S. Army inEurope acknowledged that at least 40,000 mendeserted; the British Army lost more than100,000. Many of those who deserted fash-ioned new lives for themselves in other coun-tries and were never found. Even the GermanArmy, which had a policy of shooting deserterson sight, lost more than 300,000 soldiersthrough desertion.

Developing a method of treating the victimsof combat stress took some time. In the earlydays of World War II, the U.S. Army tried sev-eral ways of dealing with the problem. At first,

10 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

National Archives

As he climbs aboard a transport off the islandof Eniwetok, a U.S. Marine wears the

expression of a fighting man who has enduredcontinued hardship.

W-Jun13 Insight_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:24 PM Page 10

psychiatric personnel attempted to screen for itduring the induction and selection process,looking for signs of psychological instability,trying to pinpoint those men who might beprone to reaching the breaking point faster thanothers. It was soon recognized that it was vir-tually impossible to predict which soldierswould fold under the stress of combat andwhich ones would not.

In 1943, a committee of 39 psychiatrists, psy-chologists, and social scientists produced a 456-page manual for soldiers called Psychology forthe Fighting Man: What You Should KnowAbout Yourself and Others. The book offeredadvice on every aspect of a soldier’s life, frommorale and training to food and sex. But itdevoted only nine pages to the topic of fear incombat.

The book took an optimistic and comfortingview about feeling fear in battle, noting, “Everyman going into battle is scared, but … as soonas the fighting man is able to go into action—to do something effective against the enemy,especially if it involves violent, physical action—his fright is apt to be dispelled or forgottenbecause he is too busy to remember it.” In otherwords, a man could expect to be afraid beforea battle, particularly if it was his first, but assoon as the fighting started his fear would van-ish and he would be fine.

That advice did not work out well. The fearremained with many soldiers every time theyfaced the enemy, particularly if the actionsinvolved an especially violent clash. Nor didevacuating combat-stressed soldiers far fromthe battlefield provide positive results. In addi-tion to losing a trained soldier from future com-bat, the distance from the field seemed toworsen the condition of combat neurosis.

Then in 1943, along came Captain Freder-ick Hanson, an Army neurologist and neuro-surgeon, whose assignment was to deal withhundreds of combat-stressed soldiers after thedisastrous defeat of American troops at Kasser-ine Pass in North Africa. Hanson made twomajor decisions that radically transformed theway victims of combat stress were treated.

As historian Stephen Budiansky wrote,“Hanson’s first step was to emphasize the nor-mality of such reactions. He ordered psychi-atric cases to be termed ‘exhaustion.’ The termwas not just a euphemism. Hanson found thata significant number of cases were no morethan the result of men being driven past theirlimits of endurance through lack of sleep dur-ing days of frontline fighting.”

Hanson arranged for the soldiers to be givena bed and food close behind the lines and theninjected them with sodium amytal and other

calming drugs, often referred to as “Blue 88,”named after the highly effective Germanartillery piece, the 88, which was also highlyeffective in knocking people out. The drugsinduced a long, deep sleep lasting up to 48hours. When the men awoke and the numbingeffects of the drugs wore off, they were givenhot showers, fresh uniforms, and a pep talk andthen sent off to the front. Hanson’s datashowed that 50 to 70 percent were able toreturn successfully to combat within three days.

A key aspect of Hanson’s program of rapidrehabilitation was to keep those suffering fromcombat exhaustion close enough to the frontline that they could still hear the sounds of com-bat when they awoke from their drug-inducedsleep. He also insisted that patients adhere to aregular military routine during the recoveryperiod. Hanson’s approach was made officialArmy doctrine toward the end of 1943 andremained in place for the rest of the war.

Still, there were many men who could not behelped even by this program and who neverreturned to active duty. For others, the fear ofreaching the breaking point would stay withthem long after the last battles were over; theirwar did not end in 1945. What we now callpost-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), butwhich had no name or formal treatment pro-grams during World War II, did indeed affectmillions of returning World War II veterans.Most of them struggled on their own to dealwith the terrors of their private war, not evenconfiding in their families or telling anyone elsewhat they had experienced.

“The increasing dread of going back intoaction obsessed me,” Eugene Sledge wrote in1981, more than three decades after the warwas over. “It became the subject of the mosttortuous and persistent of all the ghastly warnightmares that have haunted me for many,many years. The dream is always the same,going back up to the lines during the bloody,muddy month of May on Okinawa. Itremained blurred and vague, but occasionallystill comes, even after the nightmares about theshock and violence of Peleliu have faded andbeen lifted from me like a curse…. All who sur-vived will long remember the horror theywould rather forget.” nn

Duane Schultz is a psychologist who has writ-ten a dozen military history books includingInto the Fire: The Most Fateful Mission ofWorld War II and Crossing the Rapido: ATragedy of World War II. His most recent bookis The Fate of War: Fredericksburg, 1862. Heis currently working on a book on the MarineRaiders of World War II.

JUNE 2013 WWII HISTORY 11

W-Jun13 Insight_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:24 PM Page 11

GREAT BRITAIN’S MILITARY INTELLIGENCE LEADERS LEARNED FR OM THEIR experience in World War I that the kinds of minds capable of breaking codes are a rare commodityand are often not likely to blossom in a military atmosphere. As World War II approached, theGovernment Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), a name deliberately underplaying the unit’simportance, was moved out of bomb-vulnerable London.

For its new home, the chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, an eccentric million-aire named Hugh Sinclair, purchased the Bletchley Park estate in the town of Bletch-ley, Buckinghamshire. It was a nondescript manufacturing community some 50 milesnorthwest of London. But for Sinclair the important fact was that it was also a rail-way center, located on a main line out of London and another line that connected itto Oxford and Cambridge. In August 1939, as World War II loomed inevitably, Bletch-ley Park became Britain’s codebreaking center, making use of the strange old eyesoreof a mansion on the property while new structures were built when needed.

To head up GC&CS, Sinclair chose Alastair Denniston, who had shown bril-liance as a codebreaker in Britain’s Great War intelligence center, Room 40, in Lon-don. Settling down quickly to his assignment, Denniston realized that cracking new

I By Hervie Haufler I

The Miracle of Bletchley Park

Allied intelligence personnel,including Americans, at secret locations in Britian helped win the war against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

codes such as the Germans’ machine-basedEnigma system demanded special mind-sets,individuals with advanced mathematical skills,puzzle solvers, chess players, bridge addicts. Herecruited such individuals, mainly from Cam-bridge and Oxford and launched a cryptogra-phy course to begin their training.

To have British codebreakers set apart in theirown small world was in contrast to the intelli-gence decisions of other countries. They, includ-ing the United States, left their intelligence forcesembedded in their military systems.

For the Germans in particular, this was a dis-astrous decision. The Nazi forces includedmany very bright individuals, but there were somany chiefs contending for Hitler’s favor, witheach of them zealously guarding his own turf,

that the capable minds amongthe Wehrmacht’s forces were toofragmented to be effective.

The result of all this was thatBletchley Park became a meltingpot of special talent. When thewar began, three of Britain’s mas-ter chess players were attendingthe international Chess Olympicsin Buenos Aires, Argentina. Theypromptly caught the blacked-out,unconvoyed steamer Alcantara

German soldiers operatean Enigma machine, send-ing classified informationencoded through a systemof rotor settings that were

believed to be virtuallyimpossible to crack. How-ever, Allied cryptanalystsat Bletchley Park were

reading top secret Germancommunications for sometime during World War II.

12 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Top SecretU.S. Air Force

W-Jun13 Top Secret_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:42 PM Page 12

W-Next Ten FP1 Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 6:03 PM Page 2

for home and joined Denniston’s team atBletchley.

GC&CS was, in short, a society ruled byintellectual merit. Measures such as militaryrank did not count. Saluting was abandoned.No one was ruled out for being over age. Indi-viduals were known by first names or nick-names. Gaining respect was a matter of doinga superlative piece of intelligence work. Brightwomen were signed on, whether in uniform orcivilian dress.

I know personally of all this because, whenmy bad eyesight ruled me out of enlisting inanything other than the U.S. Army SignalCorps, I was trained as a cryptographer andchosen as one of the Americans to participatein the British codebreaking program.

The task of my small contingent of cryptana-lysts was to help operate a radio intercept stationat Hall Place, a derelict manor in Bexley, Kent,that provided both our work space and our liv-ing quarters. Our station, codenamed Santa Fe,operated around the clock, so we were dividedinto three shifts. We knew we were part of aBritish system because we had phone links withthe lovely British female voices at Bletchley Park,which we knew of only as Station X. On theiradvice, we broke up our large contingent ofhighly trained radio operators and assigned each

of them to a specific German military network.Collecting their transcripts, we teletyped thoselabeled “KR” for “urgent” via a secret line to Xwhile holding less timely ones for Jeep transportto be picked up in London.

We cryptographers had been promoted to therank of private first class as soon as our train-ing in the United States had ended. At HallPlace, as we watched the arrival of our ranks ofradio operators, we knew we were doomed toremain pfcs. The operators had for years been

assigned to a listening post in Newfoundland,and as they entered we saw nearly every sleevebristling with noncommissioned officerinsignia. We were right. After four years I wasdemobbed as a pfc.

Because secret military information is ruledby the “need to know,” we pfcs at Santa Fenever learned whether these messages we werehandling so carefully were ever broken. InDecember 1944, there came a morning whenmy group, just off duty, agreed mournfully over

14 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

The elegant, stately façade of Bletchley Park today belies the nature of the top secret intelligence workthat was conducted on the grounds of the estate during World War II.

W-Jun13 Top Secret_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:42 PM Page 14

the dregs of our coffee that we had beeninvolved in a thankless British game, a game inwhich message forms were merely beingstacked up in some Limey warehouse awaitingthe possible day when Station X would beginbreaking the code. The reason for this despairwas the terrible surprise of Allied soldiers beingmassacred in the Battle of the Bulge. The onlyway that this slaughter could be explained, wetold ourselves, was that the codebeakers at Sta-tion X were not solving the Nazi messages.

Still, for us there was nothing for it except tocontinue to do all we could to supply our inter-cepts fully and correctly to X.

The result of all these limitations on learningabout our role in World War II was that onbeing demobilized postwar, we still had littlereal knowledge of what part we had played.When the time came for me to sign my demobpapers and I had to pledge not to reveal or dis-cuss my wartume duty, I sniffed in disdain.“Who cares?” I asked myself. And I had to holdthat negative opinion for some 30 years becausethe British placed a security clamp on us whilethe Cold War raged.

When the British themselves began to letdown the walls of secrecy, what a joy it was,then, to discover the real stories of World WarII codebreaking. Also I learned the truth aboutthe Battle of the Bulge. In his last-ditch effort tosave his regime and himself, Adolf Hitler hadplanned that his attack in the Ardennes wouldbe directed without the use of radio. Commu-nications were handled primarily by motorcy-cle couriers.

Allied commanders were so accustomed toreceiving advance word of German decisionsthat they were caught completely off guard bythe Ardennes offensive. Supreme Allied Com-mander General Dwight D. Eisenhower wasattending his valet’s wedding in Paris, whileBritain’s Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery,commander of the 21st Army Group, was play-ing golf in Belgium and had received Ike’s per-mission to go back to England to celebrateChristmas with his family.

For me the most important of these long-delayed revelations concerned my wartime ser-vice, the assurance that my fellow cryptanalistsand I in Bexley had been, we really had been,participants in a critically important phase of thewar. Oh, how my eyes devoured those firstbooks about the triumphs, not at Station X butat what was really Bletchley Park. Along withmy excitement at learning about Bletchley, Iappreciated the wisdom of the British in settingup a nonmilitary structure there, in seeking outthose rare individuals who could excel in code-breaking, in giving them the opportunity to con-

JUNE 2013 WWII HISTORY 15

W-Jun13 Top Secret_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:42 PM Page 15

tribute to Allied victory no matter what theirgender, their age, or their sexual orientation.

If I needed a prime example, there was AlanTuring. Turing was an eccentric young man whowould never have been accepted by the military.For one thing, he was a closet homosexual at atime when Britain imposed harsh treatment onthose who were exposed. Well after the war’send, when his true sexual nature was revealedwhile his great World War II contributionsremained secret, he was subjected to such repul-sive “healing” methods that he committed sui-cide rather than further endure his treatment.

When war descended on Britain in 1939,though, Turing’s strange combination of talentscame to the fore. He was a theoretical andmathematical genius, yet he could descend fromhis visionary cloud to become the most practi-cal mechanic. This duo of virtues enabled himto lead Bletchley’s attack on the German codemachine, the Enigma.

Earlier, in the 1920s, Polish cryptographershad broken the Enigma and had been using amachine they called the “bombe” to read theGerman messages. Turing, though, saw that thePolish analysts were doing this in the wrongway. Their bombes attacked the Germanmachine through the message key indicators,which could be changed overnight, forcing theanalysts to start over again.

With astonishing speed, Turing created aBritish bombe that passed over the indicators toextract the key from the message itself—a solu-tion that permitted all Enigma messages to bebroken until, usually a day later, a new key wasemployed. His bombe possessed the power of12 Polish bombes.

Turing’s powerful and independent mindmade him, even as a schoolboy, intolerant ofconventional classroom teaching. Frequently heneglected his studies because his real attentionwas given to probing advanced mathematicaltheorems on his own.

Nevertheless, as his chief biographer AndrewHodges reported, Turing won a scholarship toCambridge and did so well there that he fol-lowed by winning a fellowship at the univer-sity’s King College when he was only 22. Atthat time, the world of advanced mathematicswas centered in the United States at PrincetonUniversity. In 1936, Turing went there to studyunder such mathematical leaders as Albert Ein-stein. Princeton Ph.D. in hand, Turing returnedto Britain in 1939, just in time to create hisbombe and lead the attack on the Enigma.

Still, he needed the help of another unmartialEnglishman to make his system work effec-tively. This was the overage Gordon Welchman,a lecturer in mathematics at Cambridge. Tur-

ing’s approach to cracking the Enigma was tolook for “cribs,” or “probable words,” in amessage. And it was true that German opera-tors punctiliously paid respectable attention toproper officerial titles and the like. To have hismachines looking for small strings of letters,however, did not produce enough rejectionsand led to too many “stops” that were foundto be false only by hand testing. It was whenTuring showed his plans to Welchman that, ina flash of inspiration, Welchman invented atechnique which, in his own words, “greatlyreduced the number of runs that would beneeded to insure success in breaking an Enigmakey by means of a crib.” His idea was incor-porated into the production of a new series ofbombes being produced by the British Tabu-lating Machine Company.

We Yanks at Hall Place didn’t learn about all

of this inspired work by these incredibly giftedEnglishmen until long after the war. Moreimmediately, we had to deal with problemsoccasioned by our location just south of Lon-don. We were on the flight path that Germanbomber crews most often followed on theirway to bomb the city. If a German crew metwith heavy antiaircraft fire, it was likely tounload its bombs short of the real target andhead for home. These times were, for us GIs,scary enough when there were German planesup there, but they became even scarier whenthe Nazis began firing their V-weapons. Theserockets could be fired high over us before crash-ing down without warning.

Our outfit won two Purple Hearts. One wasgranted to a GI who, on his night off, wasshacked up with his British girlfriend when abuzz bomb hit the house. The other was moredeserving. This GI, a private first class, was aradio operator whose set was located near theback wall of the operations room. When a V-2crashed down just short of the hall there, it blewout several windows. The glass above this GIshattered and fell on him, severely cutting hisscalp. Even though blood was running down hisface, he never stopped copying his network.

Judging the situation, the sergeant quicklyordered a reserve radio operator to tune in onthe pfc.’s net. When the operator signaled hewas tuned in, the sergeant bent over the injuredoperator and told him he could stop copying.The GI just waved him away. The sergeant thenseized the guy’s pad and yanked it away fromhim. The GI leaped up, trying to reach his pad,and screamed, “You dumb bastard, can’t yousee I’m copying?”

On being demobilized at war’s end, my matesand I had to sign pledges not to reveal what ourduties had been. For me and some 10,000 oth-ers involved in the codebreaking, these pledgeswere honored all through the Cold War, aperiod of some 30 years. Then the British them-selves began allowing officers at Bletchley Parkto write about their experiences. I bought theirbooks, eager to read official accounts of whatwe had achieved.

There was one thing lacking in these Briishmemoirs. None of them ever mentioned thatthere were Americans involved. My reactionwas to write a book of my own, Codebreakers’Victory, telling of the contributions made bythree different groups of us GIs. nn

A intelligence veteran of World War II, HervieHaufler is the author of numerous works onthe war’s intelligence history, including Code-breakers’ Victory and The Spies Who NeverWere, available from E-Reads books.

16 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

ABOVE: In Hut 3 at Bletchley Park, civilian andmilitary personnel work together to decipher

intercepted German communications. BELOW: Alan Turing, a theoretical and

mathematical genius, led the Allied effort atBletchley Park to decode and distribute

intercepted German communications transmittedvia the Enigma encoding machine.

W-Jun13 Top Secret_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:42 PM Page 16

M-Matterhorn FP Dec12_Layout 1 4/3/13 6:02 PM Page 2

IT REMAINS ONE OF THE GREAT ICONS OF WORLD WAR II. SOLDIERS EITHERloved it or hated it. Often overused because of convenience but regarded in high esteem by thosewho needed it, it left a lasting impression on the men who consumed it.

During its six years of production, millions upon millions were churned out by an array ofAmerican companies under U.S. government contract. Designed as a lightweight ration that air-borne troops could carry in their pockets, it provided a nutritionally balanced meal with enoughcalories to keep a soldier functioning for several days in the field when all other food sources werecut off. It also gave GIs a taste of home in the form of candy, chewing gum, and cigarettes.

This is the K Ration.Some five years before America entered World War II, the War Department tasked

the Army’s Quartermaster Corps and its newly formed Subsistence Research andDevelopment Laboratory (SR&DL) located in Chicago to categorize field rations anddevelop new ones to replace the obsolete Reserve Ration in use since the end ofWorld War I. An alphabetic system was designed to identify rations based on use.

Field Ration A, typically served in dining halls or aboard ships, provided at least70 percent of the freshest meat and produce available. Field Ration B, mostly served

I By Richard A. Beranty I

The World’s Best FedArmy The K Ration fed millions of American troops

and refugees during World War II.

in field kitchens, substituted canned foods whenfresh goods or refrigeration were not available.

Field Ration C, or combat rations, was devel-oped in the late 1930s and consisted of smallcans of ready-to-eat meat and bread products.Its first major procurement of 1.5 million rationswas made in August 1941, and over the next 40years the “C Rat” evolved many times in variety,quality, and packaging, becoming the longestlived compact field ration in U.S. military his-tory. It gave fighting men a well-balanced mealand did not spoil. Drawbacks were its bulkinessand weight. It was discontinued in 1981 withthe advent of the Meal, Ready to Eat (MRE).

Field Ration D or emergency ration was anersatz chocolate bar designed to give soldiersenough energy “to last a day.” Proposed in1932 for the cavalry, developed in 1935, andfirst produced in large numbers in 1941, the DRation was not your everyday Hershey bar.Comprising bitter chocolate, sugar, oat flour,cacao fat, skim milk powder, and artificial fla-voring, the D Ration could withstand temper-atures of 120 degrees without melting. GIsfound it untasty and difficult to eat. In fact,package directions advise that it be eaten slowly“in about a half hour” or dissolved by crum-bling into a cup of boiling water. Quartermas-ter records show 600,000 D Rations were pro-cured in 1941 and nearly 1.2 million in 1942.With so many on hand, none were procured in1943, but the following year some 52 millionwere ordered. By 1945, the QuartermasterGeneral was wondering how to get rid of thevast stockpile of D Rations.

With two distinctly different field rations beingreadied for mass production—Rations C andD—and war seemingly imminent, the WarDepartment recognized the need for a nutritious,nonperishable, and, most importantly, easy tocarry ration that could be used in assault opera-tions by Army airborne troops. Again it turnedto the SR&DL, which enlisted the help of a rel-atively unknown physiologist named Ancel Keysof the University of Minnesota. Dr. Keys’s mostnotable study up to that time had taken place afew years earlier in the Andes Mountains ofSouth America where he examined the body’sability to function at high altitudes.

“I suppose someone in the WarDepartment had the crazy ideathat because I had done researchat high altitude I was thereforequalified to design a food ration tobe eaten by soldiers who had beenbriefly a few meters above theground,” Keys wrote later.

A pair of hungry American tankers ofthe VII Corps pause

to eat K Rations duringa break in the fighting

in Belgium in December 1944.

18 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

OrdnanceNational Archives

W-Jun13 Ordnance K Rats_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:30 PM Page 18

W-Next Ten FP2 Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 6:03 PM Page 2

Colonel Rohland Isker, commander of theSubsistence Lab, was the man who approachedKeys for help. In 1941, the two visited a Min-neapolis grocery store and purchased 30 serv-ings of hard biscuits, dried sausage, chocolatebars, and hard candy. Picked to test the newration was a platoon of soldiers at nearby FortSnelling. Though the soldiers consumed thefood “without relish,” according to Keys, itwas given a second trial run at Fort Benning,Georgia, then home to the Army’s paratrooperschool. With comfort items such as gum, ciga-rettes, matches, and toilet paper added, the air-borne troops gave it a thumbs up and the WarDepartment followed suit.

In May 1942, the Army placed an order withthe Wrigley Chewing Gum Co. to package onemillion rations. Officially named U.S. ArmyField Ration K in honor of Keys, the Army hadfound its answer for a ration that provided “thegreatest variety of nutritionally balanced com-ponents within the smallest space.”

The concept was simple: a daily ration ofthree meals—breakfast, dinner, and supper—

that gives each soldier approximately 9,000calories with 100 grams of protein. Withinmonths, scores of food, cereal, candy, coffee,tobacco, and other companies were producingcomponents for and packaging K Rations.

If the concept was simple, so were the com-ponents. The breakfast unit contained a four-ounce can of chopped ham and egg with open-ing key, four K-1 biscuits, or energy crackers,four K-2 compressed graham crackers, a two-ounce fruit bar, one packet of water-soluble cof-fee, three sugar tablets, four cigarettes, and onepiece of gum.

The dinner unit contained the same, exceptpasteurized process American cheese replacedthe meat component, dextrose tablets replaced

20 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

ABOVE: U.S. Army K Rations supplied soldiersin the field with a high-calorie, lightweight meal when more substantial field kitchen orfood preparation facilities were unavailable.

The K Ration weighed 32.86 ounces with threemeals packed into separate boxes. It contained3,726 calories. RIGHT: Photographed before

the outbreak of World War II, K Rationdesigner Ancel Keys lived to the age of 100 andbecame famous for his research and conclusionson the linkage of smoking, high cholesterol, and

high blood pressure to heart disease.

W-Jun13 Ordnance K Rats_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:30 PM Page 20

the fruit bar, and lemon juice powder replacedthe coffee.

The supper unit differed with a can of beefand pork loaf, a two-ounce D Ration instead ofdextrose tablets, and a packet of bouillon pow-der in place of lemon juice powder.

All items fit snugly into an inner box justunder seven inches long surrounded by anouter box. The meat component and cigaretteswere packed separately with the remainingitems sealed in a laminated cellophane bag. Aday’s ration of three units weighed just overtwo pounds.

The ration was much ballyhooed by the WarDepartment at the time in posters and magazineadvertisements through its Office of War Infor-mation. Army Signal Corps publicity photosshow each item and describe its purpose: meatand cheese canned products for protein; K-1 bis-cuits for starches, carbohydrates, and minerals;K-2 graham crackers for roughage, vitamins,and starches; fruit bar for energy and vitamins;D Ration, sugar, and dextrose for energy; lemonjuice powder for vitamins and minerals; bouillonpowder for protein; cigarettes for a satisfyingsmoke; and chewing gum for thirst and tension.

The reverse side of these photos, which aredated December 30, 1942, reads as follows:“Now going into large scale production afterrigid, scientific tests in the field, the U.S. Army’sField Ration ‘K’ is playing a vital part in help-ing to keep the ‘world’s best-fed army’ well fedthe world over even under combat conditions.The ration unit consists of three packagedmeals—breakfast, dinner, and supper—eachone containing a well balanced variety of appe-tizing, nourishing foods. Chewing gum isincluded to conserve water and relieve nervoustension. Specially concentrated foods furnishthe necessary vitamins, proteins, minerals andcarbohydrates.”

Research to improve the ration continued overthe next months and years. Chocolates and hardcandy replaced the dextrose tablets, D Rations,and fruit bars. A compressed cereal bar andorange juice powder were added to the breakfastunit, matches to the dinner unit, and toilet paperto the supper unit. The meat component evolvedtoo. Late-war supper units featured corned porkloaf with carrots and apple flakes. To protect thecigarettes from being bent during shipment andstorage, a thin cardboard sleeve was added tosurround the meat component.

The companies that produced these productsand their brands reads like a Who’s Who of cor-porate America. Some examples include H.J.Heinz and Republic Foods—meat component;Peter Paul’s and Charms—candy; Nescafe—coffee; Miles Laboratories—lemon juice pow-

JUNE 2013 WWII HISTORY 21

W-Jun13 Ordnance K Rats_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:30 PM Page 21

der; Jack Frost—sugar tablets; Beeman’s,Wrigley’s, and Dentyne—gum; Camel, Chester-field, Philip Morris, Fleetwoods, and Marvels—cigarettes.

K Ration packaging evolved as well duringthe war. Early-war outer cartons contained onlythe meal title and packager’s name, such asWrigley, Heinz, The Cracker Jack Co., Ameri-can Chicle, Hills Bros., General Foods, Kel-logg’s, even whisky maker Hiram Walker andSons. Mid-war cartons added the menu andsome directions concerning food preparation.Late-war rations differed the most in that thebrown or at times olive drab cardboard gaveway to a distinctive color code, called in somecircles either camouflaged or “morale” style.Breakfast units were printed in red, dinner unitsin blue, and supper rations in green. They alsocontained a malaria warning, instructions onhow the inner cellophane bag could be used asa waterproof container, and for security pur-poses, printed directions that the empty can andused wrappers should be hidden.

For the most part, the inner carton did notchange during the war. It was dipped in a solu-tion of paraffin and bee’s wax to seal its contentsfrom the elements. Very early units included awax paper wrapping, but this was quickly aban-doned due to cost. An added bonus to GIs wasthe fast-burning properties of the wax. Soldiersfound it ideal to heat the ration’s meat compo-nent when set on fire. Both inner and outer boxeswere perfect complements to each other, as theouter carton protected the wax coating on theinner box from rubbing off and sticking to otherboxes. Typically 36 meals or 12 rations werepacked into wooden crates weighing 40 pounds

for shipment overseas.The exact number of K Rations produced in

World War II is hard to determine. After thegovernment’s initial order in 1942 of one mil-lion, at least another million were procured in1943, and 105 million in 1944, its peak year ofproduction.

There is no question that the unpopularity ofthe K Ration with American soldiers can betraced to its misuse. Familiarity breeds contempt,and it was not uncommon for GIs to discardeverything except the candy and cigarettes. Tes-timonials abound from soldiers nowhere nearthe battlefield being issued the ration. Othersreport it was given to them for weeks on end.While there were times when that practice wasnecessary, there were also times when it was usedbecause the K Ration was the easiest to issue.

There is also no question that Keys’s vision ofa small, lightweight, nutritious ration was asuccess. Paul McNelis, a decorated veteran ofthe Italian campaign with the 85th InfantryDivision, has high praise for the ration.

“On the line we survived on K Rations,” hesaid. “Mules brought them up the mountains atnight along with ammunition and water. Wewere happy to get them. C Rations were betterof course. They had more of a variety like hamand beans. But we didn’t get any since they werebulkier, and we were being supplied by mules.

“If you were on the line, K Rations weren’tthat bad. One good thing about them was thatthe box was impregnated with wax. There wasjust enough that when you set them on fire, itwould warm a cup of coffee. A buddy of mineshowed me how to make toasted cheese. Youopen the can, stick your bayonet in it and holdit over that fire to melt the cheese, and then putit on the crackers.”

With the end of World War II and peace athand, there obviously was no longer a need forassault rations. The days of the K Ration werenumbered. In 1946, an Army food conferencerecommended that its production be discontin-ued. In 1948, the Quartermaster Corps fol-lowed suit and declared the K Ration obsolete.

While the usefulness of the K Ration on thebattlefield faded into history, its inventor wouldgo on to worldwide fame. Ancel Benjamin Keyswas born January 26, 1904. A gifted intellectual,researcher, and scientist, he read in the obituarynotices of the Twin Cities newspapers shortlyafter the war that a high number of Minneapo-lis business executives, wealthy men who pre-sumably had some of the most lavish diets in theworld, were dying from cardiovascular diseasewhile people in postwar Europe, those withmore modest diets, were not.

Following a 10-year study, Keys concluded

22 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Library of Congress

Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in theMediterranean, General Dwight D. Eisenhowersits on the ground to eat a C Ration during aninspection of Allied troops in Tunisia in 1943.

The C Ration fed hungry American soldiers intothe 1980s.

W-Jun13 Ordnance K Rats.qxd *22+23_Layout 1 4/5/13 11:24 AM Page 22

that smoking, high blood pressure, and elevatedcholesterol levels were common factors in heartattack patients. That led to his landmark SevenCountries Study in which he proposed thatdietary fat is directly related to heart disease,and saturated fat in food is a determining fac-tor in blood cholesterol levels. His revolution-ary and bestselling book Eat Well and Stay Wellpopularized the so-called Mediterranean dietwith its emphasis on regular exercise and a dietrich in plant foods, fresh fruit, and fish, land-ing him on the cover of Time magazine in 1961.

Keys retired from the University of Min-nesota in 1972 and remained physically activefor the rest of his life. He died on November 20,2004. When asked at his 100th birthday partywhether his diet had contributed to his long life,he reportedly answered, “Very likely, but noproof.”

Today, Keys’s legacy lives on for collectors ofWorld War II memorabilia. Complete KRations that show up on Internet auctions rou-tinely sell for more than $200. Single compo-nents, even empty boxes, also sell well. But anote of caution to potential buyers of KRations: while an unopened box might appearto be in pristine condition, collectors havefound there is a very good chance that the con-tents have been sampled—by worms. nn

Richard Beranty is a retired teacher of highschool English and journalism who resides inWestern Pennsylvania.

JUNE 2013 WWII HISTORY 23

National Archives

During combat operations in Italy in October1944, soldiers of the 91st Infantry Divisionrest against a rocky outcropping and eat K

Rations. The K Ration was relatively easy totransport, and it was alternately loved and

hated by GIs the world over.

W-Jun13 Ordnance K Rats.qxd *22+23_Layout 1 4/5/13 11:24 AM Page 23

MANY STUDENTS OF WORLD WAR II HIST ORY KNOW GENERAL SIR CLA UDEAuchinleck as the Commander-in-Chief Middle East, who, after taking over for General Sir ArchibaldWavell in late June 1941, oversaw the fluctuating fate of Britain’s Eighth Army while combating Ger-man General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps during Operations Crusader and Gazala.

It was after General Neil Ritchie’s humiliating defeat along the Gazala Line that Auchinleck tookover direct control of the Eighth Army and fought Rommel to a standstill in July1942 at the First Battle of El Alamein. However, this Indian Army general had aneventful career leading British and Allied troops in Norway in the spring of 1940as well as in the British Isles from July through November 1940 before his returnto India to become commander of the Indian Army in January 1941. Those earlyAuchinleck commands were quite uncharacteristic for an Indian Army general giventhe rivalry of that organization with the regular British Army.

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, nicknamed “the Auk,” was bornon June 21, 1884, in Aldershot, England. He was the eldest child of Lt. Col. John

I By Jon Diamond I

Auchinleck of the IndianArmy

Prior to his arrival in North Africa, the British commander primarily ledIndian troops and performed well in difficult circumstances during the campaign in Norway.

Claud Alexander Auchinleck of the Royal HorseArtillery, stationed at Aldershot. The youngerAuchinleck was of Anglo-Irish-Scottish descent,which was to characterize the origins of many anoteworthy British Army officer.

When Auchinleck was a year old, his fatherreturned to Bangalore, India, to command theRoyal Horse Artillery there. In 1888, while hisfather was serving in the Third Burma War,Auchinleck returned to England with hismother and siblings. His father, having retiredfrom the Army in 1890, died two years laterfrom a form of anemia putatively contractedduring his Burmese service. As a result of his

father’s death, his childhood and early adult-hood bordered on poverty.

In the fall of 1896, Auchinleck attendedWellington, located near Sandhurst, at a drasti-cally reduced fee since he was an officer’s son.In 1901, he sat for the entrance examination forthe Royal Military College at Sandhurst sincehis lackluster mathematics performance atWellington precluded the Royal Military Acad-emy at Woolwich, the training ground for gun-ners and engineers. He placed 45th on the Sand-hurst examination, taking the last placeallocated to the Indian Army, and entered theacademy in 1902. He was among 30 cadetsreceiving their commissions in the Indian Armythe following year.

With five other officers from Sandhurst, 2ndLt. Auchinleck was temporarily sent to the 2nd

King’s Shropshire Light Infantry(KSLI), a British battalion havingrecently seen action in SouthAfrica. After a winter attached tothe British regiment, he joined the62nd Punjabis, an Indian Armyregiment, in April 1904, to whichhe was permanently posted. Auchinleck rose to the rank of

A British artillery batteryfires at German positions

during the Battle ofNarvik, along the bleakNorwegian coastline, in

June 1940. British GeneralClaude Auchinleck com-

manded troops during thedisappointing campaign.

24 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Profiles

All images, Imperial War Museum

British General Claude Auchinleck and Royal AirForce Group Captain M. Moore confer during

operations in Norway.

W-Jun13 Profiles_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:33 PM Page 24

W-Macromark FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/3/13 6:04 PM Page 2

captain during 11 years of peace in India,which were shattered by World War I. Up tothat point, he had never fired a shot in anger.However, he did learn a number of local lan-guages and bonded with his troops by beingable to converse fluently with them.

Auchinleck, initially bound for France, wasdetoured along with his 62nd Punjabis (as partof the 22nd Indian Infantry Brigade) to Suez andthe defense of the area around the canal fromBritain’s new enemy, Ottoman Turkey. It was inearly February that Auchinleck received his bap-tism of fire as the Turks attempted to cross theSuez Canal at Ismailia. After defeating this Turk-ish attempt to take the Suez Canal, Auchinleck’sregiment embarked for Aden in July 1915 tosuccessfully eject the invading Turks in that Pro-tectorate.

In December 1915, the 62nd Punjabi Regi-ment was ordered to the Persian Gulf andMesopotamia, and thus Auchinleck avoided thecarnage of Gallipoli, the brainchild of his fellowSandhurst cadet, First Lord of the AdmiraltyWinston Churchill. Disembarking at Basra onJanuary 7, 1916, for the offensive up the TigrisRiver to Baghdad, Iraq, Auchinleck, now an act-ing major and second in command of his regi-ment, witnessed nearly a 50 percent casualty rateduring a month of campaigning against the well-entrenched Turks. A second major attack, thistime along the right bank of the Tigris to relieveKut in early March 1916, also failed largely dueto a background of hasty and unimaginativeplanning and administrative incompetence.

Auchinleck summed up his regiment’s condi-tion in April 1916 as “exhausted, decimated andwith our morale badly shaken.” The chaos inlogistics he experienced was to foreshadow thecommand role Auchinleck inherited during theAllied attack on Norway in 1940.

By the autumn of 1917, Auchinleck wasregarded as an officer of promise and meritori-ous achievement, and he became the brigademajor of the 52nd Brigade as part of the new17th Indian Division. Auchinleck was men-tioned in dispatches and received the Distin-guished Service Order in 1917 for his service inMesopotamia. He was promoted to major inJanuary 1918.

Soon after the armistice, Auchinleck becamea general staff officer (GSO) 2 with the divisiongarrisoning Mosul, Iraq. In August 1919, asGSO 1 of a division, he was ordered to pacifyKurdistan. For his excellent staff work he wasagain mentioned in dispatches and made abrevet lieutenant colonel. At the end of 1919, hewas offered a vacancy at the Staff College atQuetta, which was recognized as a “gateway toadvancement” in the Indian Army. There, he

was outstanding among the younger IndianArmy officers who had survived the Great War.

In 1923, Auchinleck was stationed at Simla,India, as a British staff officer, and after fouryears he returned to his regiment, now renamedthe 1st Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment. In1927, Auchinleck, having been recognized as“one of the outstanding Indian Army officers ofhis generation,” was posted to the ImperialDefence College (IDC). While at the IDC,Auchinleck made a valuable friendship withGeneral Sir John Dill, the chief instructor there.After his stay at the IDC, Auchinleck returnedto his regiment in India. At the end of 1928,Auchinleck was appointed to command hisown battalion. In February 1930, he returnedto Quetta as GSO 1 at the Staff College with therank of full colonel. It was a two-year course,and he was in charge of 30 officers in the juniordivision in their first year.

Later, in command of the Peshawar Brigade,

Auchinleck led a short punitive expeditionagainst the Mohmands in 1933. For this expe-dition, he was awarded the title of Commanderof the Bath (CB). In 1935, during another expe-dition against the Mohmands as a juniorbrigadier, he made a close professional associa-tion and friendship with the forces’s seniorbrigadier, Harold Alexander. After this expedi-tion’s successful conclusion, he received theCompanion of the Order of the Star of India(CSI) and another mention in dispatches. Uponbeing promoted to major general, Auchinleckhanded over command of the Peshawar Brigadeto Brigadier Richard O’Connor, anotherWellington graduate.

From 1936 to 1939, Auchinleck was theDeputy Chief of the General Staff (DCGS), Indiaand Director of Staff Duties in Delhi. In early1938, Colonel Eric Dorman-Smith, anotheryoung staff officer of high intellect and profes-sional achievement, was appointed Director ofMilitary Training at Army Headquarters inSimla. There, both his work with Auchinleckand their mutual habit of long morning walksforged a strong bond of friendship and profes-sionalism. This relationship would later flourishin the Western Desert in 1942, as the duo over-saw the successful defense of Egypt during theFirst Battle of El Alamein, after the defeat alongthe Gazala Line, when the victorious AfrikaKorps was threatening to capture the SuezCanal and the Middle East.

In July 1939, Auchinleck and his family vis-ited the United States as war clouds were loom-ing over Europe. While he was sailing back toIndia, war broke out. Soon thereafter he took upa new position as commander of the 3rd IndianDivision. During the Phony War, he continuedto train his troops. In January 1940, he wasordered to return to England to take commandof the IV Corps before its deployment to north-ern France around Lille as part of the BritishExpeditionary Force (BEF) in June of that year.The IV Corps was composed of British Regularand Territorial Army units, with most of the for-mation being untrained. A “Sepoy General”was now in charge of a large British Army force.

Auchinleck was isolated and lonely in his newIV Corps command, largely because the BritishRegular Army in the higher officer ranks was atightly knit and closed community. Auchinleckalso felt somewhat inferior to the Regular Armyofficers of the conventional English upper classbecause of the relative poverty of his youth andadulthood. To Auchinleck’s endearing credit, helacked the snobbishness of the British RegularArmy. Instead, he exuded professionalism,which was an anathema to English upper classsociety. With his focus on professionalism, he

26 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

ABOVE: French troops man a position some-where in Norway. General Auchinleck was

complimentary of the conduct of the French sol-diers under fire but bitterly disappointed withthe performance of his own men during the

1940 Norwegian campaign. BELOW: A group ofBritish World War I veterans muster as LocalDefense Volunteers during the dark days as

Britain stands alone against the Nazis. GeneralClaude Auchinleck led Southern Command as the

British prepared for a German cross-Channelinvasion that never materialized.

W-Jun13 Profiles_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:33 PM Page 26

W-Hurrycane FP Jun13_Layout 1 4/4/13 12:01 PM Page 2

shared a common trait with a junior competitor,future Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

On April 9, 1940, the Nazis, who had a non-aggression pact with Denmark, neverthelessinvaded and forced a surrender of that countrywithin hours. Also on that date, the Germansseized Oslo, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, andNarvik in Norway despite that country’s neutralstatus. The Allies decided to counterattack withthe most suitable objective being Narvik, eventhough it lies within the Arctic Circle. Thisstrategic decision was based upon the recom-mendation of the British Military CoordinationCommittee under the chairmanship of noneother than Winston Churchill, again serving asFirst Lord of the Admiralty.

The objective was to establish a naval basefor the Allies in the far north of Norway, whichcould be a staging area to seize the Galliväreiron ore fields in Sweden. To achieve this,Narvik had to be retaken. Although other oper-ations were proceeding badly against the Ger-mans in central Norway, the Narvik attack wasto deliver the major thrust against the Nazis. Asevents unfolded, it did no better than the moresouthern operations despite a British naval vic-tory over a German destroyer force in the OfotFiord leading into Narvik.

On April 28, Auchinleck was ordered to reportto the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS),General Sir Edmund Ironside. The CIGS, whowas soon to be replaced by General Sir John Dill,informed Auchinleck that he and part of the IVCorps staff were going to Narvik. To emphasizethe divide between the British Regular Army andthe Indian Army, Ironside gave Auchinleck abackhanded compliment by describing him as

“the best officer India had, who was not conta-minated by too much Indian theory.”

Auchinleck replaced the local ground forcescommander in northern Norway, Maj. Gen.Pierse J. Macksey, who was faulted for beingtoo deliberate in his approach to secure the portof Narvik. However, Auchinleck could see noway to speed up the British advance.

There were reasons for the faulty perfor-mance of the BEF under Auchinleck’s com-mand. There were few reliable maps of the area,and RAF air cover was spotty at best early in thecampaign. While Auchinleck was at sea headedfor Norway, there was a two-day debate in theHouse of Commons on the conduct of the Nor-way campaign that led to the ouster of PrimeMinister Neville Chamberlain’s government.

The day before Auchinleck’s arrival in Nor-way, the Nazi blitzkrieg through the Low Coun-tries had commenced, and Churchill had beenappointed prime minister. With attentiondiverted now to northern France and Belgium,it is easy to draw the conclusion that Narvik hadturned into almost a backwater. Near the end ofMay, it was determined that Allied forces innorthern Norway were to be evacuated. How-ever, Narvik should be captured to facilitate theoperation.

With Narvik in his hands, Auchinleck had tothrow all of his energy and leadership to the taskof evacuation with the minimum possible casu-alties. In his correspondence to Dill on May 30,Auchinleck commented, “The news from Franceis grim and every one is depressed by it, natu-rally. However, there is no sign of defeatism sofar as I can see. This is a queer show into whichyou have put me!... One feels a most despicable

creature in pretending that we are going on fight-ing, when we are going to quit at once.”

The evacuation began on the night of June 3.Cloud cover, Auchinleck’s determination to keepBritish antiaircraft guns in action to the last, andthe RAF’s ceaseless sorties from its base at Bard-foss all contributed to a smooth military with-drawal, which was completed by June 7. Auchin-leck had been on Norwegian soil for just underfour weeks. The Auk realistically drew his ownhistorical analogy about the Napoleonic Wars inhis correspondence with Dill. “We are in thesame position as were Napoleon’s adversarieswhen he started in on them with his new orga-nization and tactics! I feel we are much too slowand ponderous in every way.”

Auchinleck had learned some pragmaticlessons from his experiences in northern Nor-way. First, “To commit troops to a campaign inwhich they cannot be provided with adequateair support is to court disaster.” Second, “Nouseful purpose can be served by sending troopsto operate in an undeveloped and wild countrysuch as Norway unless they have been thor-oughly trained for their task and their fightingequipment well thought out and methodicallyprepared in advance. Improvisation in either ofthese respects can lead only to failure.”

Two paragraphs of Auchinleck’s report thatwas completed on June 19, 1940, and subse-quently printed for the War Cabinet in March1941, had been suppressed during the war andwere only to reappear in July 1947. “The com-parison between the efficiency of the Frenchcontingent and that of British troops operatingunder similar conditions had driven this lessonhome to all in this theatre, though this was notaltogether a matter of equipment. By compari-son with the French, or the Germans for thatmatter, our men for the most part seemed dis-tressingly young, not so much in years as in self-reliance and manliness generally. They give animpression of being callow and undeveloped,which is not reassuring for the future, unless ourmethods of man-mastership and training forwar can be made more realistic.”

Auchinleck would have his chance to trainBritish troops in southern England, NorthAfrica, and India where they would all provetheir mettle and receive the Auk’s accolades.

After the Norwegian debacle, Auchinleck wasinstructed to form V Corps for the defense ofsouthern England. This would be an under-strength corps of two divisions, virtually with-out heavy equipment, along a stretch of about100 miles. Auchinleck observed firsthand thatthe British troops in Norway were inexperi-enced and the new V Corps would be no betteroff. Hard training lay ahead if a Nazi invasion

28 WWII HISTORY JUNE 2013

Wearing distinctive pith helmets, British soldiers assume prone positions as their commander scans thehorizon for enemy activity. These troops were photographed near Ramadi, Iraq, as the British attempted

to secure Middle Eastern oil reserves.

W-Jun13 Profiles_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:33 PM Page 28

were to be either repelled or contained. On July 19, 1940, Auchinleck received

another promotion barely a month after hisorders to the V Corps assignment. He was nowto take over Southern Command. The V Corpswould become the domain of Lt. Gen. Mont-gomery, back from divisional command in thefailed BEF operation in Flanders. The two wereat odds continuously, with the critical nature ofthe times preventing Auchinleck from sackingMontgomery. Auchinleck, like Rommel fouryears later in Normandy, wanted to meet theGerman invasion on the beaches; however,Montgomery argued vociferously for maintain-ing strength in reserve behind the beaches todestroy the Germans after they had secured aweak lodgment.

Auchinleck was also praised for the mannerwith which he constructed the Home Guard,which eventually became a reasonable militaryasset rather that a militia’s mob. Unfortunately,many postwar accounts give Montgomerycredit for the development of Southern Com-mand and the Home Guard, even though it wasAuchinleck who had laid the foundations forthe hard training in Southern Command. Lt.Gen. Alexander took over Southern Commandwhen Auchinleck was appointed commander ofthe Indian Army in November 1940.

One of Auchinleck’s first moves as IndianArmy commander in early April 1941 was tosend several Gurkha and Sikh elements of the10th Indian Division to secure the oil pipelineterminus to the Persian Gulf at Basra, Iraq, andto set a staging point to mount operations fromthere to Baghdad and crush the Rashid Ali rebel-lion. Other troops from this division, whichwere originally earmarked for transport fromIndia to Malaya, were maneuvered by Auchin-leck to Basra with the 21st Indian InfantryBrigade, arriving on May 6, 1941, followed by25th Indian Infantry Brigade’s landing there atthe end of May.

Auchinleck’s move was in conjunction withChurchill’s ordering Field Marshal ArchibaldWavell to provide a relief force (Habforce) fromPalestine to lift the siege of RAF bases in Iraq inorder to reclaim Britain’s treaty rights from theinsurrectionist Iraqi regime. Auchinleck’sactions in Iraq pleased the prime minister.Churchill wrote to Auchinleck on May 14,1941: “We are most grateful to you for the ener-getic efforts you have made about Basra. Thestronger the forces India can assemble there thebetter…. We are, therefore, confined at themoment to trying to get a friendly Governmentinstalled in Baghdad and building up the largestpossible bridgehead at Basra.”

The prime minister further wrote of Auchin-leck: “When after Narvik he had taken overSouthern Command I received from many quar-ters, official and private, testimony to the vigourand structure he had given to that importantregion. His appointment as Commander-in-Chief in India had been generally acclaimed. Wehad seen how forthcoming he had been in send-ing troops to Basra and the ardour with whichhe had addressed himself to the suppression ofthe revolt in Iraq.”

For an Indian Army officer, Auchinleck hadperformed admirably in Scandinavia during theassault on Narvik and its subsequent successfulwithdrawal, as well as in England where hebuilt up Southern Command to become a real-istic force to contest a Nazi invasion on thebeaches. Furthermore, prior to his assignmentas Commander-in-Chief Middle East, for whichhe is most famous, he had shown initiativewhen directing his Indian Army troops to seizeBasra from Iraqi insurgents.

However, the sternest test for the Auk was tocome against Rommel in North African desert. nn

Jon Diamond practices medicine and lives inHershey, Pennsylvania. He authored an OspreyCommand Series volume on Field MarshalArchibald Wavell, published in 2012.

JUNE 2013 WWII HISTORY 29

W-Jun13 Profiles_Layout 1 4/3/13 5:33 PM Page 29

m ired in combat in the Hürtgen Forest of Germany, an American soldierwrote in December 5, 1944: “The road to the front led straight andmuddy brown between the billowing greenery of the broken toplessfirs, and in the jeeps that were coming back they were bringing the stillliving. The still living were sitting in the back seats and some were

perched on the back seats and others were sitting facing forward on the radiators because the jeepswere that crowded. You could see the white of their hasty bandages from far off and there wereothers of the still living who were on stretchers strung from the front seats to the back and on theradiators too, and the brown blankets came up to their chins. Overhead the sky was grey.”

The Hürtgen Forest encompassed about 50 square miles of rugged, densely wooded terrainalong the German-Belgian border south of Aachen, the first major German city to fall to theAllies. The area was thickly laced with mines, barbed wire, and concealed pillboxes with inter-locking fields of fire. The American First Army was tasked with capturing the forest to secure theright flank of the advancing VII Corps, to prevent the Germans from mounting counterattacksfrom its concealment, and to attack a large portion of the Germans’ fixed fortifications of theSiegfried Line from the rear.

The dominant geographic feature in the Hürtgen was near Bergstein, the Burgeberg-Castle Hill,or as the Americans called it, Hill 400 because of its height in meters, equivalent to 1,312 feet. Itssteepest slope was at a 45-degree angle, and the hill was thickly wooded with evergreens. Fromthis promontory the Germans enjoyed a commanding view of American movements and directed

both nasty artillery fire and counterattacks. No American vehicle or foot movement went undetected from this vantage point. It was thecornerstone of the German line. If the Americans seized Hill 400, itwould provide excellent observation of the Roer River, the next Alliedobjective after Hürtgen was cleared of Germans.