Wuketits Evolutionary Epistemology

description

Transcript of Wuketits Evolutionary Epistemology

FRANZ M. WUKETITS

EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY - A CHALLENGE TO

SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY

There could be no fairer destiny for any ... theory than that it should point the way to a more comprehensive theory in which it lives on, as a limiting case.

Albert Einstein

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions ... , but rather for the sake of the questions themselves ...

Bertrand Russell

1. INTRODUCTION

"In the future I see open fields for ... important researches. Psychology will be securely based on the foundation already well laid by Mr. Herbert Spencer, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation." Thus Charles Darwin wrote in On the Origin of Species;! in the sequel he announced: "Much light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."2 And Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin's famous advocate, predicted that Darwin's own work, "if you take it as the embodiment of a hypothesis ... is destined to be the guide of biological and psychological speculation for the next three or four generations." 3 Since Darwin, much light has indeed been thrown on the origin of man, his history and his place in nature, and Huxley's prediction has proved to be true.

Darwin's work was, of course, a corner-stone in the history of the biological sciences. But what has it really meant for psychology? In what way has it been a guide of 'psychological speculation'? Initially we may answer thus: Darwin's studies of man's nature at least meant a plea for intensifying theoretical and empirical work in evolutionary psychology. Unfortunately it is not yet common knowledge that - as M. T. Ghiselin has pointed out 4

- Darwin devoted a considerable part of his studies to the behaviour of organisms and therefore to psychology in its widest sense. As to human

F. M. Wuketits (ed.), Concepts and Approaches in Evolutionary Epistemology, 1-33. © 1984 by D. Reidel Publishing Company.

2 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

behaviour in his The Descent of Man (1871) Darwin worked out some evolutionary principles in relation to man's mental abilities, e.g. self-consciousness, language and morality. It is true that in some passages of this book he relied heavily on Herbert Spencer's evolutionary conceptions. However, his evolutionist view of psychological phenomena has, on the whole, been an original contribution to psychology, for, unlike Spencer's approach, it was founded on a mass of empirical evidence and did not lack scientific rigour. In general, this view means "that subhuman animals too can have a mental life, that ideation is a bodily process, and that it is subject to natural selection just like any other biofunction". 5

The evolutionary view of the human mind, proposed by Spencer and then elaborated by Darwin, consequently included an attempt to understand man's faculties of cognition and knowledge by means of evolutionary theory and particularly the theory of natural selection. Evolutionary psychology in the nineteenth century was therefore the overture to evolutionary epistemology.

In short, evolutionary epistemology is an epistemological system which is based upon the conjecture that cognitive activities are a product of evolution and selection and that, vice versa, evolution itself is a cognition and knowledge process. According to D. T. Campbell "an evolutionary epistemology would be at minimum an epistemology taking cognizance of and compatible with man's status as a product of biological and social evolution".6

In this essay I shall outline some of the basic postulates of the evolutionary view in epistemology and the systematic position of such a view in science and philosophy. Furthermore, I shall, implicitly, give a brief account of the history of evolutionary epistemology. Thus the reader may take his bearings on the different approaches to an evolutionary theory of knowledge and become aware of the interdisciplinary nexus of this theory. I also hope that the following sections will make clearer the coherence of the different contributions to the present volume.

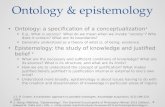

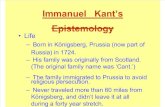

2. THE NOTION OF THE INNATE - IMMANUEL KANT

AND BEYOND

In Western philosophy since Plato it has been a matter of controversy, whether man's epistemic capacities are, in some way or another, innate. It has often been argued that there are certain dispositions, which are 'self-evident', so to speak, and that these dispositions exist before any individual learning and experience. The other point of view has been that of the tabula rasa, that is to say the assertion that knowledge can start from nothing. However, many

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 3

philosophers have assumed certain intellectual ideas as a fact a priori and, more recently, psychologists and anthropologists have maintained that mental as well as cultural and social structures depend on pre-existing patterns of pSYGhological, cultural and social organization. Table I shows, on the right, the most eminent notions of this view, and on the left, the most well known authors of these notions.7

Plato (427 - 347 B.C.) Aristotle (384 - 322 B.C.) Francis Bacon (1561 - 1626) David Hume (1711 - 1776) Rene Descartes (1596 - 1650) Gottfried W. Leibniz (1646 - 1716)

Immanuel Kant (1724 - 1804)

TABLE I

abstract ideas axioms of logic idola tribus (e.g. form perception) instincts rust principles (e.g. man's own existence) essential truths of mathematics and logic; intellectual ideas (e.g. substance)

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821 - 1894)

the 'causes' for the 'forms of intuition' (Anschauungs[ormen) and categories 'ideation of space' (three-dimensionality of space)

Konrad Lorenz (born 1903)

Jean Piaget (1896 -1980)

Carl G. Jung (1875 - 1961) Claude Levi-Strauss (born 1908)

Noam Chomsky (1928 - 1978)

elementary patterns of behaviour; 'forms of intuition' and categories 'norms of reaction'; elementary structures of perception archetypes (e.g. anima) (ethnical) 'structures' (e.g. marriage types, structures of kinship) generative grammar

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Immanuel Kant took a decisivie step by trying to reconcile two seemingly irreconcilable epistemological positions, namely empiricism and rationalism. Kant's 'critical philosophy' contains the well-known distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge. According to Kant our knowledge is in part a priori and not inferred from experience; on the other hand, it is also in part a posteriori and based on experience gained by sensory perception. If, for brevity's sake, we simplify Kant's epistemology, we can state that human knowledge is composed of both a priori and a posteriori propositions and these propositions, mutually related to each other, make possible our knowledge of the world.

Kant's assumptions also mean that much of the striking conformity

4 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

between patterns of the external world and patterns of our thought is determined by pre-existing, i.e. a priori structures, the 'categories' and 'forms of intuition' (Anschauungsformen), of any subject which experiences them.

Kant's epistemological doctrine was certainly a consistent philosophical system and a refreshing outlook. After Kant, however, one problem remained; this was the question: 'Where do a priori structures come from?' Yet in the framework of Kant's system of thought this question was not, and is not, a matter for discussion. But beyond this system and especially with regard to an evolutionary interpretation of man this is an intriguing question. Since Kant science and philosophy - except for the 'idealistic philosophy' -have been confronted again and again by the relativity of categories. Here we can find a connection between Kant and modern evolutionary theory, between Kant's 'apriorism' and the evolutionary explanation of epistemic phenomena. Evolutionary epistemology is mainly an attempt to explain a priori structures of our knowledge via evolution and to 'dynamize' these structures.

Does this mean that evolutionary epistemology is a reversed Kantian philosophy? Let us, first of all, take a look at two very recent evolutionary attempts to explain man's cognitive faculties: the conceptions of Konrad Lorenz and Rupert Riedl. 8 The approach of Lorenz has been an ethological one, whereas Riedl's view primarily relies upon comparative biology and was the result of a theory concerned with the order in living systems, i.e. a systems approach to organismic evolution.9 In both cases Kant's categories of thought and intuition can be seen as evolutionary products.

Lorenz has argued that evolution is a cognition process and that life is, in general, a process of learning; and he has exposed the innate teaching mechanisms which are prerequisites for the surival of any species. In his own words, "one has to postulate the existence of innate teaching mechanisms in order to explain why the majority of learning processes serve to enhance the organism' fitness for survival"; 10 furthermore, "these mechanisms ... meet the Kantian definition of the a priori: they were there before all learning, and must be there in order for learning to be possible." 11 Riedl summarizes his view as:

Among all cognitive methods possible, the one which recognizes the environment most efficiently and reliably had to be selected ... The prerequisites of human thinking, though a priori for each individual in the sense of Kant, are a posteriori for the chain of his pedigree. 12

These have been biological approaches to the relativity of the a priori. But

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 5

it is also necessary to mention here the epistemologcial view of Karl R. Popper, as a recent philosophical approach which results in an evolutionary conceptionP When Popper's theory is compared to the theories of Lorenz and Riedl, it turns out that these are different approaches to the same problem and with the same results. Popper writes: "I contend that the leading ideas of epistemology are logical rather than factual; despite this, all of its examples, and many of its problems, may be suggested by studies of the genesis of knowledge." 14 This contention shows that Popper attached great importance to an evolutionary perspective in epistemology. Moreover, his own contribution to such a perspective has become obvious in regard to the philosophy of science or, in a narrower sense, in regard to methodology. I here refer to his studies of the 'nature' of hypotheses and/or theories. A brief quotation may suffice in this context:

... the growth of our knowledge is the result of a process closely resembling what Darwin called 'natural selection'; that is, the natural selection of hypotheses: our knowledge consists, at every moment, of those hypotheses which have shown their (comparative) fitness by surviving so far in their struggle for existence.! 5

Thus, Popper advocates, as Campbell had already deomonstrated,!6 a 'naturalselection epistemology' or, a 'natural-selection methodology'.

The basic idea underlying these evolutionist conceptions (K. Lorenz, R. Riedl, K. R. Popper) is that

(i) cognition, be it in the subhuman or in the human world, cannot start from nothing and that, therefore,

(ii) the existence of inborn mechanisms is very probable. So the first postulate 0/ evolutionary epistemology can be firmly stated as follows:

All organisms are equipped with a system o/innate dispositions; no individual living system is initially a 'clean slate' or tabula rasa.

Innate dispositions, like the above-mentioned inborn teaching mechanisms, are by no means static structures, but rather are dynamic elements of an organismic system, products of evolutionary processes. Any modern theory concerned with the notion of innateness must be based on the phenomenon of evolution and, consequently, on a dynamic world view. The emergence of evolutionary thought in the course of the nineteenth (and, though just allusively, even the eighteenth) century was rendered possible by the 'dynamization of the world view' and the abandonment of the classical notions of scala naturae, which had greatly influenced philosophical and scientific

6 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

thinking from Plato to the forerunners of Darwin (e.g. J. Lamarck)P Hence the second postulate of evolutionary epistemology is this:

Innate dispositions are the outcome of natural selection; they are the products of selective mechanisms, which, among all 'initial products', favour and stabilize the one which best copes with the conditions of living and surviving.

The behaviourist's failure is, despite the grain of truth of some behaviouristic presuppositions, the overestimation of learning in the life of the individual organism. Some behavioural patterns of a living being are possibly acquired through individuallife-experience and introjected by the environment; the great error of behaviourism, however, arises "from forgetting that adaptedness to environment can never be a coincidence but must necessarily have a history explaining it." 18 That should be enough to refute the behaviouristic doctrine.

Since Darwin the evolutionary interpretation of innate mechanisms has been adopted by many researchers. The history of these interpretations is largely an account of evolutionary interpretations of the Kantian a priori; and it is, par excellence, the history of evolutionary epistemology. Campbell has already provided a historical perspective on evolutionary epistemology.19 I shall refer to Campbell's account, and I shall also refer to other scholars not mentioned in his review.

Among biologists, about a hundred years ago, the famous German evolutionist Ernst Haeckel in his popular writings clearly expressed the phylogenetic relativity of the human mind and, implicitly, interpreted man's cognitive abilities by the means of evolutionary theory in the sense of Darwin's 'selectionism'.20 Haeckel, therefore, was a forerunner of evolutionary epistemology in a more recent sense, although his 'biological philosophy' was, on the whole, a rather one-sided view. Independent of and opposed to the Darwinian method of looking at evolution, the French Philosopher Henri Bergson and the German biologist Jakob von Uexkilll at the beginning of the twentieth century proposed a view similar to that of evolutionary epistemology, a view which is of a certain significance for the evolutionary theory of knowledge. Bergson and von Uexkii11 continued the vitalist tradition and partly rejected Darwin's theory,21 but it is not possible to offer here a detailed description of Bergson's and von Uexkiill's conceptions. However, it might be sufficient to recall their assessments of plan and purpose in living nature and von Uexkiill's notion of the Umwelt. Likewise Georg Simmel, anticipating Bergson and von Uexkilll, noted "that the phenomenal worlds of animals differ from one to the other, according to the particular aspects of the world they are adapted to and the different sense organs they have." 22

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 7

As regards the 'dynamization' of the Kantian approach, we must be aware of some authors, primarily biologists, who since the foundation of evolutionary theory have pleaded for a reorientation in epistemology, i.e. for a biological theory of cognition and knowledge. In some cases, of course, the interpretation of the a priori by the means of evolutionary biology has been considered only briefly and not explicitly. But some authors have stated the phylogenetic relativity of categories quite obviously. For example, a book by the German biologist Paul Flaskiimper surprisingly has a chapter entitled 'Biological Epistemology' and Flaskiimper's attitude towards biological conceptions of knowledge transgresses the boundaries of Kantian philosophy.23 Since the 1940s many biologists have emphasized the approach to epistemology 'under the auspices of evolution'. Let me give some examples.

Ludwig von Bertalanffy: the founder of modem systems thinking, discussed the problem of the relativity of categories thirty years ago. At a later date, in his General System Theory (1968), he summarized: "Cognition is dependent, firstly, on the psycho-physical organization ... "; and he continued: "The categories of experience or forms of intuition, to use Kant's term, are not a universal a priori, but rather they depend on the psychophysical organization and physiological conditions of the experiencing animals, man inc1uded."24

Although not speaking of the Kantian a priori, Julian Huxley and George G. Simpson also argue that cognition and mind depend upon biological structures and fucntions, i.e. that there is a biological foundation of what we call 'mind' .25 Likewise, most recently and independently of the abovementioned expositions of Lorenz and Riedl, the following authors adopted the evolutionary view of cognitive capacities both subhuman and human: Erich Jantsch, Hans Mohr, Jacques Monod, Bernhard Rensch and Conrad H. Waddington.26 The eminent psychologist Jean Piaget also explored the pathways of psychological development in children and expounded his genetic epistemology.27 It is important to note Eric Lenneberg's account of the biological foundations of human language 28 and also Noam Chomsky's concept of generative grammar.29 I shall refer below to psychological, linguistic and anthropological notions, in so far as they have been relevant to evolutionary epistemology.

There is one idea common to the approaches considered so far namely that of the biological relativity of mind. In other words, according to the authors quoted in these passages, the human mind is dependent on man's anatomical and physiological organization, that is to say dependent on organic entities and is thus a product of evolution. The third postulate of

8 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

evolutionary epistemology - which is tacitly accepted, of course, by all who have taken an evolutionary view in epistemology, can therefore be formulated as follows:

All psychic phenomena in the subhuman world as well as mental abilities proper to human systems (selfconsciousness) are based on biological structures and functions; biological evolution has been the precondition to psychological and spiritual evolution.

But there are some differences between the psychological and the spiritual or mental: psychological phenomena are common to all organisms which show a nervous system or similar structures performing a similar function on a lower level; spiritual or mental phenomena, however, depend on a specific arrangement of nerve cells (neurons) and are due to specific brain activities appearing only in human systems. Neither psychological nor mental states and processes are explicable without reference to the organic level, i.e. the ensemble of nervous, sensory and brain elements. Thus, man's mental life can only be understood by studying its neurobiological bases, as F. Seitelberger contends in the present volume. These postulates do not amount, as might be suspected, to ontological reductionism, for we do not state that the human mind is 'nothing else but an arrangement of organic elements'. We rather adopt an emergentist view: psychological and mental phenomena were evolutionary novelties; patterns of interactions on the organic levelled to the emergence of these phenomena. Lorenz, consequently, writes:

There is nothing supernatural about a linear causal chain joining up to form a cycle, thus producing a system whose functional properties differ fundamentally from those of all preceding systems. If an event of this kind is phylogenetically unique it may be epoch-making in the literal sense of the word.3o

Man's mental properties certainly differ fundamentally from the system characteristics on the subhuman levels, but they are nevertheless products of evolution - evolution is, so to speak, a 'red thread',a process which, by increasing complexity, produces qualitatively new systems; this can be illustrated by a simple diagram (Figure 1).

Since the human mind is a product of evolution - and any opposite view such as that of classical dualism means a kind of 'obscurantism'31 - the evolutionary approach can be extended to the products of mind, that is to say to epistemic activities such as science. Perhaps the reader will now suspect vague analogies or even a tautological structure 32 of evolutionary

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY

organic level

psychic level

mental level

Fig. 1.

EVOLUTION

9

epistemology. But is it not evident that science, scientific inquiry since its inception three or four thousand years ago, has undergone many changes and intricate developmental processes? It certainly is evident: history of science means evolution of science. However, this proposition is not new; since the term 'evolution' has been extended to phenomena beyond the biological world, many philosophers of science have taken an evolutionary view. I shall confine myself in this treatment to some historical notes, for a model of the evolution of scientific method is discussed in more detail in the present volume by E. Oeser.33

One of the first to deal with this question was the English philosopher and scientist William Whewell. In his On the Philosophy of Discovery (1860) Whewell argued that "there are powers and faculties which do thus seem fitted to endure and not fitted to terminate and be exstinguished";34 and he also wrote:

The mind is capable of accepting and appropriating, through the action of its own Ideas, every step in sciene which has ever been made - every step which shall hereafter be made ... Can we suppose that the wonderful powers which carry man on, generation by generation, from the contemplation of one great and striking truth to another, are buried with each generation?35

It is remarkable moreover, that Whewell's Novum Organon Renovatum, which transgresses Aristotle's Organon and Bacon's Novum Organon, contains a historical relativism of the Kantian a priori and, regarding the construction and improvement of hypotheses boils down to an explanation similar to that of Popper, by fostering the idea of conjectures and refutations. 36 For this

10 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

reason Whewell, as Oeser has noticed,37 can be identified as a forerunner of the 'logic of discovery' which essentially is influenced by Popper's thought.

What we find in Whewell, although it is not explicit, is the advocacy of a 'trial-and-error model' of scientific research. Such a model, which we may also call a 'selective elimination model', has been fully described by later authors, some before Popper; some of the most recent representatives of this model or of approximately equivalent conceptions are B. BlaZek, M. Eigen, M. T. Ghiselin, N. R. Hanson, E. Jantsch, W. Leinfellner, N. Stemmer and S. E. Toulmin.38 The basic premise of these works is that scientific research, in general, is functioning in some way analogous to and comparable with the process of natural selection, although scientific progress takes place on a higher level, that is the mental level or, to use Popper's concept, in the sphere of 'World 3'.39 Science, as a product of man's mental life, like mind itself relies upon the capacity of the human brain. The evolutionary perspective in the study of the history of science, after all, amounts to the biological relativity of scientific development.

Hence the evolutionary perspective of science gives rise to such statements as the following:

Scientific thought will always be based on whatever information-processing modes have been acquired during the early lifetime of the human brain and its early interaction with the environment. Scientific thought will always be conditioned to the limitations of current learning and teaching methods and associated intrahuman communication systems. Scientific thought will always be limited by the natural boundaries of cerebral information-processing per se. 40

In other words: scientific thought is not yet, and, presumably it will never be, completely free from man's inborn teaching mechanisms; but this should be obvious.

These statements are true of epistemic activities in toto: the message of evolutionary epistemology, as revealed by our insights into innate mechanisms, is that evolution has set bounds to the realization of human power. Consequently, the cognizance of man's own limitations, I am sure, will have to be an element of a new image of man (see section 5).

3. PATTERNS OF NATURE AND THE NATURE OF COGNITION OR, 'WHY THE EYE IS ATTUNED TO THE SUN'

The questions discussed in the foregoing section require some further explanations. We have just stated the biological relativity of mental capacities and

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 11

suggested the natural boundaries of these capacities. I now state the following thesis: the· analogy between highly sophisticated episternic systems, like science and episternic activities on the 'sub rational' , i.e. ratiomorphic 41 level is not a coincidence, but is based on isomorphic principles, that is to say structural and functional principles and/or laws common to all levels of organization.42 This thesis is a fundamental assertion of the systems theoretic view which replaces the ontological notions of the 'scale of nature'.

Classical ontology had, nevertheless, one advantage: the cognizance of the hierarchical organization of reality. Nicolai Hartman, who was perhaps the most eminent representative of the 'ontology of nature' in the twentieth century,43 specified four levels of increasing complexity in the hierarchically organized structure of the world:

(i) inorganic level (ii) organic level

(iii) psychic level (iv) mental level

Hartmann's view, however, like that of his precursors, was a rather static one, whereas the modern systems theoretic approach to understanding the texture of the world corresponds to the above-mentioned 'dynamization' of our world picture. Furthermore, systems theory in the sense of von Bertalanffy has contributed much to the improvement of our image of a dynamically organized universe. Each of the levels of reality (see Table II) describes a certain stage of complexity, arranged by interacting elements.

TABLE II

elementary particles a atoms ] molecules S' organic molecules 8 cells 00 organs .~ multi-cellular living systems ~ psychological phenomena and mind .5 social systems

cultural systems

12 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

Dynamic interactions among hierarchically organized systems are the driving forces of the emerging network of nature. These interactive relations have manifested themselves in evolution. Evolution is the dynamic principle underlying all levels of reality, and, as I have said before, the 'red thread' of nature; and it is just this process which, by the emergence of qualitatively new systems, has caused the different stages of complexity, which were already apparent to Greek natural philosophy. For about ten years it has been the notion of selforganization of matter 44 which has thrown new light on the development of the universe.

For, the external world of any subject as well as the observing subject itself are products of the very same process, that is evolution, and the conformity between patterns of the external world and patterns of subjective thought can be explained intrinsically in terms of evolution and selection. The evolution of the perceiving apparatus, i.e. the totality of information, and cognition-processing mechanisms in a living system, has been an adaptation process, and this is true in the subhuman and human spheres of the animated world. Through the process of adaptation living systems accumulate more and more information about their environment and, thus, represent the structure of the environment they live in; the better the representation of the environment, the better the chance of survival.45 (Remember the 'second postulate of evolutionary epistemology'.) The information gained about the environment is stored in the genome; thus information-processing mechanisms are analogous to learning by trial and error, whereas the storage of information functionally is performed in the same way as memory.46 So even the simplest ratiomorphic functions require rather complex 'calculating machines'.

We can now substantiate the thesis that the impressive order in nature is not, as it has been claimed by idealistic philosophy, a product of our thinking and imagination, but that, on the contrary human thought itself is a product of the emerging order in nature.47 If this thesis is not true, how does it come about that man is capable of recognizing 'his' world? Let me recall Plotin's metaphor in Goethe's words: "Were the eye not attuned to the Sun, / The Sun could never be seen by it." The eye, indeed, is attuned to the sun, because it has been developed and selected to recognize light. Certainly, neither man nor any other organism is able to represent the world exactly, but those parts of reality are represented, which are most important to be perceived for the sake of survival. The representation of reality R, therefore, is a partial one, R' (see Figure 2).

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 13

R

partial representation of reality by the erceiving apparatus

A N ISM perception -------, _-+_+-____ ~ ....... R1 : informationprocessing

Fig. 2.

I I _______ ..1

What we experience is indeed a real image of reality - albeit an extremely simple one, only just sufficing for our own practical purposes; we have developed 'organs' only for those aspects of reality of which, in the interest of survival, it was imperative for our species to take account, so that selection pressure produced this partial cognitive apparatus.48

But we must not forget that an organism itself is part of reality, and by 'reality' in this context we mean the external world of an organism.

When we consider the partial representation of reality by the perceiving apparatus, we arrive at the following conclusions:

(i) The range of perception varies from one species to another, i.e. different species perceive different parts of reality, since they are adapted to and live in changing environmental conditions. This is as clear, as that the perceiving apparatus of lower animals, as opposed to that of higher organized living systems, allows only the representation fo a small part of reality. Of course, the perceiving apparatus of, for instance a unicellular animal is much more primitive than that of a primate. Hence it follows that the 'world picture' of unicellular animals is completely different from that of mammals, and that, for example, the 'world picture' of fishes is different from that of birds, and so on. Von Uexkiill anticipated these conclusions in his Umweltlehre: 49 According to von Uexkiill any organism shows its own specific 'ambient'. I think that this concept expresses a notion closely resembling what, in evolutionary epistemology, we call 'world picture'.

(ii) The most complex perceiving apparatus and thus the most sophisticated 'world picture' among all living systems is that of man. Man's facuIties of cognition do not depend on the ratiomorphic apparatus only, for this apparatus in human beings is 'built over' by a system which is

14 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

perhaps best characterized as the rational apparatus. The emergence of the ratio has been the greatest event in the course of evolution, because it has given rise to completely new patterns of complexity and order, like art, language, science and ethical systems. However, as we have seen, man's innate (ratiomorphic) teaching mechanisms up to now have set bounds to recognizing the extensions of the world, simply because they have had to succeed in a sphere which we can call the 'mesoscosmos'. 50 The cognizance of structures and laws beyond the mesocosmos is the mission of scientific endeavour - and that is the rational venture of modern man (see section 5).

(iii) The faculties of an organism to perceive certain parts of reality and to gain a particular 'world picture' originate in a genetically stabilized program containing 'how to behave in order to survive' imperatives. This is not a mere anthropomorphism, for any organismic system is functioning by virtue of its genetically directed peculiar behavioural programs, which may be slightly modified during the individual span of life. For survival's sake any organism is equipped with a 'system of hypotheses', i.e. inborn 'ideas' of certain parts of reality.51 This 'system of hypotheses' is the initial equipment of living systems for calculating their chances of survival. A 'realistic' calculation of the structures of the external world is the precondition for coping with the specificity of the environment. Hence organisms are 'hypothetical realists'.

This conclusion leads us to the intriguing epistemological question about the naturalist's epistemological view underlying his investigations into the realm of nature. By answering this question, we lay down the fourth postulate of evolutionary epistemology:

The naturalist has to adopt the postualte of objectivity: nature is objective; it has existed before and independently of an observing subject.

The postulate of the objectivity of nature, without ifs and buts, is the basic precondition to scientific research. If nature were not real, it never could be observed. Any naturalist has to take, therefore, a realistic view. The opposite opinion could lead to a ridiculous solipsism. (But I do not believe that a scientist or a philosopher nowadays might seriously advocate a solipsistic position.) Certainly, to take the view of hypothetical realism does not mean that man is capable of recognizing the 'world in itself. Here again we have to realize. the natural boundaries to cognition and knowledge. In Popper's words we can epitomize these assertions in the following way:

The thing in itself is unknowable: we can only know its appearances which are to be understood (as pointed out by Kant) as resulting from the thing in itself and from our

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 15

own perceiving apparatus. Thus the appearances result from a kind of interaction between the things in themselves and ourselves. This is why one thing may appear to us in different forms, according to our different ways of perceiving it - of observing it, and of interacting with it. We try to catch, as it were, the thing in itself, but we never succeed: we can only find appearances in our traps. 52

All things considered, our attitude towards nature, as it is expressed in some other parts of this book, is a realistic one. Of course, we do not adopt 'pure' realism in its simplist form. Our kind of realism, I repeat is hypothetical realism. What else should we propose in view of the premise that man's perceiving apparatus, like man himself, is attuned to nature?

Such an epistemological position as is presented here, is compatible with the postulate of objectivity in science, not in the sense of the positivist's credo, but in the sense of a critical approach beyond positivism. This would be, then, a 'new criticism' transgressing the boundaries of Kantian philosophy. As Hans Albert puts it, "the methodology of knowledge must have a basis in reality: it must be appropriate to the relevant structural traits of reality." 53

And Albert continues: "This means that we must look for an appropriate theoretical basis for it in an adequate theory of knowledge, an epistemology which explains or accounts for knowledge, particularly the cognitive enterprise of science, or explains how we can learn and solve problems." 54 All this means an escape from metaphysical obscurantism.

4. THE INTERDISCIPLINARY FOUNDATION OF EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY

So far we have primarily considered some biological aspects of evolutionary epistemology. However, the references to psychological, anthropological and linguistic approaches to the notion of the ideae innatae (in section 2) have already shown the multidisciplinary plateau of an evolutionary theory of knowledge. Indeed, evolutionary epistemology does not mean an epistemological system based on biological assertions only; rather it means the convergence of various results in different fields of scientific investigation.

Evolutionary epistemology is in fact a two-level approach to the phenomenon of knowledge:

(i) First there is the level of biological evolution. On this level the evolution of cognitive mechanisms has become intelligible, i.e. the evolution of the perceiving apparatus of animals, including man. This process has been studied by means of evolutionary biology and with reference to physiology (especially neurophysiology and sensory physiology), neuro-anatomy, ethology, and so

16 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

forth. The conclusion of these studies is that, as already seen in the course of evolution living systems increasingly accumulated information about their environment, so that evolution itself can also be described as informationprocessing, i.e. a universal process of learning and cognition.

(ii) The second level is the psychological one. Psychology of development is concerned with the display of the inborn capacities and the modification of these capacities by learning during man's individual life. In a way this means that developmental psychology is the application of fundamental evolutionary principles to the psychological and mental development (ontogenesis) of man. The evolutionary perspective, certainly, is required whether psychology refers to innate capacities per se or to individual modifications of the innate:

< innate capacities

evolution ~ modifications by learning

Methodologically this leads us to the following relations between evolutionary biology, genetic psychology and developmental psychology:

< genetic psychology

evolutionary biology t developmental psychology

Note, in addition, a passage in Piaget's Main Trends in Psychology running as follows:

"On the one hand, the organic and the mental give rise to differential specializations that distinguish individuals from each other (according to tpe combinations of heredity, aptitude and history), while, on the other hand individuals share certain common general structures (mental operations, etc.), which are formed and developed in a fairly uniform way."ss

I turn now to Piaget's conception of genetic epistemology, i.e. the ontogenetical approach to the development of psychic and mental abilities in human systems.

Piaget was convinced that epistemology must be based on results from scientific investigations into the nature of knowledge. This has proved to be

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 17

the right way, and such a conviction, of course, underlies the intentions of evolutionary epistemology. A good deal of Piaget's studies is devoted to the development of cognitive functions in children. Piaget suggested examining this development like a mental 'embryogenesis' in order to fmd a fullyfledged biological theory of cognition. Between 1920 and 1970 he constantly studied the development of the child's mental abilities, e.g. conceptual thought, perception, representation of the external world, language, moral judgments, and so on. This search to understand the child's 'mental world' dynamically, was expressed in a psychogenetic or, more precisely, psychontogenetic conception. Piaget's genetical psychology and, in a wider sense, his genetical epistemology 56 have been the theoretical connection between the areas of psychological and biological research. That connection constitutes a corner-stone in the scientific foundation of epistemology, and Piaget endeavoured to establish epistemology as a scientific discipline.57 Apart from these methodological consequences Piaget's conception had a positive impact on the notion of the innate, in the sense that inborn 'norms of reaction' (mentioned above; see Table I) become visible. Such 'norms of reaction' are natural, i.e. innate limitations to the development of organisms; according to Piaget they are to be characterized as the totality of phenotypes, which potentially are produced by one genotype.

What we fmd elaborated in Piaget's work is the importance of understanding biological and psychological preconditions to mental capabilities like speech. (In what follows I use the terms 'speech' and 'language' in the same sense.) During the last decades some authors, biologists as well as psychologists, have, like Piaget, presented a conceptual scheme which amounts to biopsychological explanations and prompts us to a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon. It is common knowledge that the emergence of mind and the origin of speech are inseparably related to each other. Human language is the expression of human mind and vice versa. When we explain mind as a systems property of sophisticated human brain functions - and I do not see any justification for explaining mind via metaphysical notions -the search for understanding man's language means the search for its biological elements.58 By making such assertions, however, we do not need to behave like reductionists: Human language, undoubtedly, depends upon cultural and social circumstances as well and can be fully understood only in regard to all these components. However, the preconditions to the emergence of speech, whether phylogenetically or ontogenetically, have been biological agencies set up by brain mechanisms, vocal organs, etc. As to the evolutionary origin of language, admittedly, there are still many queries. But it might stimulate

18 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

further discussions or even solutions of some embarrassing problems, to take into consideration Ch. D. Hockett's observation that: "Man's own remote ancestors ... must have come to live in circumstances where a slightly more flexible system of communication, the incipient carrying and shaping of tools, and a slight increase in the capacity for traditional transmission made just the difference between surviving ... and dying out." 59 Hence the emergence of such a communication system as is peculiar to modem man must have been of certain biological value.

It is not possible to deal here with all the aspects of the origin and evolutionary development of speech, but I must mention one thesis which is of the greatest importance to evolutionary epistemology: this is the thesis that human language is programmed genetically, i.e. that "human genes carry the capacity to acquire language, and probably also a strong drive toward such acquisition", whereas "the detailed conventions of anyone language are transmitted extragenetically by learning and teaching." 60 Speech, therefore, depends on innate dispositions common to all human systems; the existence of such innate 'language capacities' seems to be self-evident to us. Moreover, this biologically founded thesis conforms to the linguistic approach to universal patterns of grammar, which has been promoted by the studies ofChomsky.61 In short, Chomsky's view can be recapitualted as follows: man's capability of language is based on innate structures, i.e. genetically established potentials of speaking. Thus, a universal (generative) grammar underlies any special expression of speech; the different languages, like English, French, Russian, etc., are modifications of that elementary structure, and they are due to cultural influences, social circumstances, and so on.

So we now come to the cultural relativity of categories. 62 Besides the two-level approach to evolutionary epistemology, set up by biological and psychological concepts and data, cultural anthropology has provided material which at least may be interpreted in an evolutionary sense and fit in the framework of evolutionary epistemology. As to the linguistic approach, let me note en passant that this approach connects the bio-psychological and the anthropological spheres, for language cannot be !lxplained without reference to both the bio-psychological and the cultural anthropological view.

A reciprocal relationship between language and culture may be suggested: on the one hand the structure of language depends on specific patterns of culture, on the other hand culture, and even our whole world perspective, depends on the potential of language. Remember in this context the 'Whorfian Hypothesis', according to which the structure of language in a high degree determines the 'world picture'.63 However, it is true that epistemic activities

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 19

in genere are 'preformed' by cultural evolution.64 By stating this we attain to cultural relativism, which was espoused by von Bertalanffy, M. J. Herskovits, and others. Herskovits wrote: "Even the facts of the physical world are discerned through the enculturative screen so that the perception of time, distance, weight, size and other 'realities' is mediated by the conventions of any given group."65 Whether you take such a view absolutely or not -physical reality is real, despite its perception, as stated in the postulate of objectivity, but it can be interpreted in various forms; and these forms of interpretation (or explanation) ultimately depend upon cultural circumstances.66 Thus, philosophical systems, for instance, differ from one 'cultural circle' to another, which is obvious if you look at the differences between Western and Oriental philosophy.67

But irrespective of the prima facie differences, e.g. in writing, art, codes of morals, etc., Levi-Strauss 68 has pointed out that on the level of structures there are elementary patterns of culture. (Structures, in this context, are expressed in, for example, myths, symbols, types of marriage, and so on.) Levi-Strauss believes that different ethnical systems might be reduced to some common 'grounds' or even (cultural) 'universals'. Although this analogy is rather daring, there are similarities between such universals and the Kantian a priori, and one might say that cultural universals are something like cultural a priori categories.

I hope that this brief sketch has made clear the interdisciplinary context of evolutionary epistemology. There is still much work to do done to put together the biological, the psychological, the linguistic and the anthropological/ethnological approach to a common methodological matrix (i.e. evolutionary epistemology; see Table III) which could meet a philosophical desideratum: namely that of a comprehensive, consistent epistemological system transgressing the boundaries of 'classical' epistemological doctrines, which have often been presented in a somewhat dogmatic fashion. I hope that the present 'volume will contribute to the urgently needed new epistemology (see section 5).

Finally, we can stress the fifth postulate of evolutionary epistemology:

Evolutionary epistemology is an interdisciplinary approach to explaining and understanding epistemic activities; it is based on biological and psychological research and corresponds with results in the fields of linguistics, anthropology, ethnology and sociology.

In conclusion, we must take into account the mutual relation between

EV

OL

UT

ION

AR

Y

DE

VE

LO

PM

EN

TA

L

AN

TH

RO

PO

LO

GY

B

IOL

OG

Y

PS

YC

HO

LO

GY

evol

utio

n o

f liv

ing

deve

lopm

ent o

f pa

tter

ns o

f or

gani

za-

syst

ems

beha

viou

r o

f in

-ti

on i

n et

hnic

al s

yste

m

divi

dual

hum

an

syst

ems

------------

-----------

--

--

--

--

----

subh

uman

and

hu

man

wor

ld

hum

an w

orld

hu

man

wor

ld

leve

ls o

f liv

ing

sys-

psyc

hic

leve

l cu

ltur

al a

nd s

ocia

l te

rns:

mol

ecul

es, c

ells

, {m

enta

l lev

el)

leve

l or

gans

, or

gani

sms,

po

pUla

tion

s

gene

tic

prog

ram

s in

nate

cog

niti

ve

patt

erns

of

cult

ural

st

abil

ized

in

the

abil

itie

s an

d so

cial

org

aniz

a-co

urse

of

evol

utio

n ti

on c

omm

on t

o

by

nat

ural

sel

ecti

on

diff

eren

t sy

stem

s ('

stru

ctur

es')

EV

OL

UT

ION

AR

Y

EP

IST

EM

OL

OG

Y

LIN

GU

IST

ICS

stru

ctur

e o

f lan

guag

e in

hum

an s

yste

ms

------------

hum

an w

orld

men

tal

leve

l

gene

tic

prog

ram

o

f gr

amm

ar

.... '"

(I)

'"

r6.s

:.

e: (I

)

goa 0 ....,

g" ta

~ ::s

§ a-

,,'

0 ':'

....,

....

..

..

(I)

(I)

~

[g

e: ~

" '"

::>

'0 ....,

i I

>-l >

I:C

t""'

tr1 .... .... ....

tv

o 'Il

:;tI >

Z

N a: :e c::

l"':

tr1

>-l ::J CIl

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 21

evolutionary epistemology and those branches of scientific investigation: on the one hand, evolutionary epistemology depends on the results of several scientific disciplines, on the other hand it incorporates initially isolated results into a unified theory and thus feeds back into these discplines, and in that sense, it helps us to understand their results. This relation may be demonstrated by a simple diagram (Figure 3).

biology --: ___ ~

.~ e psychology .s '"

---.~ .s. ~ I-:~=======:::;: <1) ....

.... " o 2 linguistics ____ oS t;

~

anthropology •

Fig. 3.

evolutionary epistemology

I shall now set out some consequences which might be deduced from the foregoing items and which might also point to fields open for both scientific (empirical) research and philosophical contemplation.

5. THE CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY

According to the foregoing statements, evolutionary epistemology means new scientific and philosophical frontiers. So far, I have tried to outline the guiding ideas and the primary goals of evolutionary epistemology and to point out its basic postulates with reference to its history (sections 2-4). But, in addition to this, it is essential to outline the position of an evolutionary theory of knowledge in the system of science and philosophy and to point the way to some innovations, which might arise as consequences of the evolutionary outlook.

(a) Towards a New Image of Man

I shall start with a quotation from an essay by G. Radnitzky: "We need a self-conception of man in which above all man's capacity of knowing is realistically grasped: which admits that there is cognitive progress ... ,

22 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

that there are indicators of cognitive progress whose fallibility in principle must not only be admitted but be emphasized, but whose objectivity is to be insisted on." 69 That is correct - we need a new self-conception of man, a new image of man going beyond misleading dogmas. Unfortunately, our world view has often been governed by illusive styles of thinking, i.e. myths, metaphysics, ideological claims,70 which have very often obscured man's view of himself and, thus, have put obstacles in his search for enlightenment. So what is to be done? We have to adopt a comprehensive system of thought which conforms to the goals of objective knowledge; and we have to abandon obscuratism and illusionism.

In order to adopt such a system of objective knowledge, we have to fulfIl., above all, one demand: we have to learn from our own evolution. As I pointed out above, man is not free from his innate teaching mechanisms. The dilemma, which has arisen from these conditions is that man's innate teaching mechanisms were selected in prehistoric times for survival's sake in a world which differs greatly from our world of today; the ratiomorphic apparatus succeeded under the circumstances of man's evolutionary past, the ratiomorphic algorithms were sufficient for our ancestors, but they do not fully cope with today's world and, consequently, man is often misdirected.71 This can be convincingly shown by the conception of causality. 72

The cognizance of causal relations, obviously, is based upon, and phylogenetically programmed as, the recognition of causal chains. However, if we look at complex systems like organisms, cultures, social organizations, and so on, and if we try to explain their complexity, we shall easily understand that all these systems are built up by sophisticated patterns of interaction among their elements. In order to explain such systems we have, then, to consider another conception of causality, namely feedback causality. The inborn expectation of linear causality, the inborn 'cause-effect notion', sufficed within a rather simple 'life-world', the 'life-world' of Australopithecines, for instance; but it does not suffice to control man's present situation.

So what does a new image of man imply with respect to such insights into man's ratiomorphic apparatus? We can answer as follows: a new image of man implies man's view of his evolutionary past, which is still present and not yet overcome. Our postulate is to take into account man's cognitive structures, which were evolved (selected) in the past, but which have refused to work reliably in the 'life-world' of modern man.

One might suspect that man is an evolutionary 'overshoot'; and one might suspect that evolution, when coming to the emergence of our species has come to a deadlock, a hopeless situation. "To be sure, mankind also

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 23

finds itself in greater danger than ever before", 73 writes Lorenz and he seems to confirm this apprehension. But note his ensuing statement: " ... the modes of thought that belong to the realm of natural science have, for the first time in world history, given us the power to ward off the forces that have destroyed all earlier civilizations." 74 In other words: we can still master our situation, iff we make use of human reason, iffwe make use of objective knowledge, which, in the last resort, we can obtain by the means of evolutionary epistemology. At any rate, a re-orientation is necessary.

(b) Towards Rationality and Objective Knowledge

In section 3 I mentioned that evolutionary epistemology is apt to meet the standards of objectivity in scientific research. Campbell also came to the conclusion that evolutionary epistemology and evolutionary perspective in general "is fully compatible with an advocacy of the goals of realism and objectivity in science" 75 . This recalls our attitude towards hypothetic realism, I think that Popper has already proved this assertion in his works.76 Moreover, I should say that evolutionary epistemology does not only conform to scientific objectivity, but that it has also provided the foundations of objective knowledge, for within the framework of an evolutionary theory of knowledge the phylogenetic preconditions of human reason 77 have been made clear, so that the following relations are given:

ratiomorphic mechanisms

-----evolutionary epistemology

human reason (rationality)

I objective knowledge

Man's innate teaching mechanisms indeed have set bounds to his development as a biological species; but man as the animal rationale has transgressed his status as mere animal and, as it were, has opened completely new dimensions. Thus it is true that we are not influenced by ratiomorphic structures only - these structures yet continue man's status quo ante, but the animal rationale by definition is endowed with reason, too. Therefore, we have

24 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

to use reason and to act rationally. When we do so, we have the adventure of objective knowledge, we have scientific enterprise, and for the first time a living being is able to investigate the sphere 'behind the scenes' of its own existence. This has been the great evolutionary novelty.

(c) Towards a New Epistemology

The evolutionary theory of knowledge paves the way for are-orientation in epistemology. Up to now epistemology has usually been said to be a philosphical discipline and so the problem of knowledge has been considered a philosophical one. This is not quite true as the problem of knowledge belongs rather to the intersection of science and philosophy. Epistemology, then, eo ipso is an 'inter discipline' or, as W. Leinfeilner and G. Vollmer, for example, pointed out,78 a 'metadiscipline'.

Evolutionary epistemology offers convincing evidence of the urgently needed interdisciplinary foundation of epistemology. Since the set of problems of knowledge has been discussed in terms of traditional philosophy by the majority of epistemologists, it is no wonder that epistemology was not, and is not, able to get rid of its intriguing questions. However, as I showed in section 4, during the last decades biologists, psychologists, anthropologists and linguists have been attracted by these questions and accumulated more and more data about phenomena like perception, conceptual thought, learning and so on.

We assume that such phenomena are to be discussed in terms of the empirical sciences, because the central question of epistemology is this: 'What is knowledge and how does it arise?' Thus we are justified in claiming a new epistemological system going beyond the traditional boundaries of scientific and philosophical thought. Such an epistemological system would be a comprehensive, scientifically founded theory of knowledge without metaphysical claims: it would be an elementary epistemology 79, dealing explicitly with the above-mentioned question. Indeed, the task of any epistemology should be to investigate the preconditions of cognition and/or knowledge, i.e. to investigate the ratiomorphic mechanisms and so, first of all, to explain what we may call common-sense knowledge, for rationality, scientific and philosophical thought start from common sense,so which, we repeat, is itself a product of the evolution of life.

Hence it follows that evolutionary epistemology is an integral part of, and the theoretical, as well as the empirical, prerequisite to an elementary epistemology. By stating this, the position of evolutionary epistemology is

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 25

already indicated. Our assertion can be specified by a simple diagram showing the relations between ratiomorphic mechanisms, common-sense knowledge and epistemology:

ratiomorphic common-sense evolutionary mechanisms ----~ .. ~ knowl,d", ~ 'PMrOlOgy

~ elementary epistemology

Thus, common-sense knowledge is subject to an elementary epistemology. Scientific knowledge has grown from common-sense knowledge and has outgrown it, as a generalized and objectified form of knowledge.S! Science is man's most sophisticated epistemic activity, and, at least on our planet, man is the only one living being which has created science. The system of science is based on rationality,S2 and "knowledge for the sake of understanding, not merely to prevail, this is the essence of the scientific approach." S3 SO science is taking place on the highest level of man's mental states, but it cannot be explained without reference to common-sense knowledge and its evolutionary preconditions.

The relation of epistemology to philosophy of science follows:

ratiomorphic common-sense scientific -----~ -----~ mechanisms knowledge knowledge

I I elementary philosophy epistemology .. of science

Finally, I express my hope that scientific knowledge will be applied to man's highest aspirations and that it will not fall a victim to fateful ideologies.

6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The present essay is an outline of evolutionary epistemology. It is concerned with

26 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

the notion of the innate and its phylogenetical interpretations (section 2), the isomorphic relation of patterns of nature to patterns of cognition (section 3), the interdisciplinary matrix of evolutionary epistemology (section 4), and some of the consequences of the evolutionary view in epistemology (section 5).

Implicitly I have given a brief historical sketch of evolutionary epistemology and have pointed out five basic postulates of an evolutionary theory of knowledge.

This essay, primarily, should attract the reader to the evolutionary perspective in epistemology, which is a rather new outlook, although its forerunners go back to the nineteenth century (H. Spencer, C. Darwin, E. Haeckel, and others). I have tried to outline the program of evolutionary epistemology; the following chapters will show the many facets of this program.

Yet there is resistance to evolutionary epistemology,84 due to misunderstandings and to 'open problems'. I hope that the present volume, firstly, will contribute to the elimination of misunderstandings and, secondly, will be an encouragement to further studies, be it in science or in philosophy. However, I am sure that evolutionary epistemology at least will prove to be an 'eye opener' for many in the quest for understanding man.

NOTES

1 C. Darwin (1859), see 1958 edition of New American Library of World Literature, p.449. 2 Ibid. 3 T. H. Huxley (1863), see 1960 edition of University of Michigan Press, p.144. 4 Cf. M. T. Ghiselin (1969). 5 M. Bunge (1979, p. 53); see also M. Bunge (1980). Cf. my remark on p. 8. 6 D. T. Campbell (1974, p. 413). 7 Cf. G. Vollmer (1975, p. 91) and F. M. Wuketits (1981, p. 114). 8 See K. Lorenz (1973) and R. Riedl (1980). Lorenz developed his evolutionary theory of knowledge in the 1940s and anticipated his phylogenetic interpretation of Kant's 'apriorism' in a paper published 1941 (see Bibliography). For further details see Riedl in the present volume, pp. 35-50. 9 Cf. R. Riedl (1975, 1976). Riedl'presented a summary of this theory and its consequences for epistemology in his article published in The Quarterly Review of Biology 1977 (see Bibliography). 10 K. Lorenz (1973), quoted from 1977 edition of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, p. 89. For a review of "the evolution of life as a cognition process" see R. Kaspar (1980).

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 27

11 K. Lorenz,op. cit., p. 89. 12 R. Riedl (1977), p. 367. 13 Popper adopted an evolutionary view - independent of but, as it were, parallel to Lorenz - in the 1930s and 1940s; see his Autobiography (1976). An exhaustive treatment of evolution and epistemology is Popper's Objective Knowledge (1972); see, in addition, K. R. Popper (1959, 1969). On Popper's evolutionary epistemology see W. W. Bartley (1976). 14 K. R. Popper (1972), p. 68. 15 Ibid., p. 26l. 16 D. T. Campbell, op. cit. 17 See e.g. F. M. Wuketits (1980). 18 K. Lorenz (1965), p. 23. 19 Cf. D. T. Campbell, op. cit. 20 See e.g. E. Haeckel's Weltriithsel (1899). 21 Cf. H. Bergson (1907) and J. von Uexkiill (1928). 22 D. T. Campbell, op. cit., p. 438. See also in Campbell's treatment, references to William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, James Mark Baldwin, Jules Henri Poincare and Ernst Mach, and on Mach see also E. Oeser's contribution in this volume, pp. 149-84. 23 Cf. P. Flaskiimper (1913). 24 L. von Bertalanffy (1968), p. 240 and p. 245. 25 Cf. J. Huxley (1957) and G. G. Simpson (1963). 26 See E. Jantsch (1975), H. Mohr (1967,1977, and in the present volume pp. 185-208), J. Monod (1970), B. Rensch (e.g. 1968, 1977), C. H. Waddington (1954), J. Z. Young (1971). Except for Monod and Waddington these authors are not mentioned in Campbell's op. cit. ; some references see also in G. Vollmer, op. cit. 27 Cf. 1. Piaget (1970). 28 Cf. E. Lenneberg (1967). 29 Cf. N. Chomsky (1968). 30 K. Lorenz (1973), see 1977 edition of Harcourt Brace Jovanich, p. 30. See, furthermore, e.g. R. Riedl (1976,1980) and F. M. Wuketits (1978b, 1981). 31 It is noteworthy that dualism is represented even today by some neurobiologists (fortunately not by many!); see e.g. 1. C. Eccles in K. R. Popper and J. C. Eccles (1977), part II. 32 Gunter Wagner, in the present volume (pp. 283-305), tries to show from the logical point of view that evolutionary epistemology is no tautological explanation of the phenomena it is concerned with. 33 See pp. 149-84; see also E. Oeser (1976), vol. III. 34 W. Whewell (1860), see 1972 edition of Franklin, p. 395. 35 Ibid., p. 396. 36 Cf. K. R. Popper (1969). 37 Cf. E. Oeser, op. cit. 38 Cf. B. Blazek (1978), M. Eigen and R. Winkler (1975), M. T. Ghiselin, op. cit., N. R. Hanson (1958), E. Jantsch, op. Cit., W. Leinfellner (in the present volume, pp. 233-76), N. Stemmer (1978), S. E. Toulmin (1967). From another point of view W. F. Gutmann and K. Bonik (1981, and in former writings), though criticizing evolutionary epistemology, have adopted a conception similar to that of the 'trial-and-error model'. For references to authors between 1850 and 1970 (e.g. A. Bain, S. Jevons, P. Souriau, and

28 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

others) see again D. T. Campbell,op. cit. Furthermore, the reader will fmd some aspects of the evolution of science in H. Mohr (1977), R. Riedl (1980), F. M. Wuketits (1978b) and in the collection of papers edited by I. Lakatos and A. Musgrave (1970); last, but not least remember T. S. Kuhn (1962). 39 Cf. K. R. Popper (1972) and K. R. Popper and J. C. Eccles (1977). 40 1. G. Roederer (1979), p. 103. 41 The term 'ratiomorphic' was introduced by E. Brunswik (1955) to characterize cognitive faculties similar to but not identical with rational structures and mechanisms. Cf. K. Lorenz (1973), R. Riedl (1980). 42 I presented this thesis at the 'Fifth European Meeting on Cybernetics and Systems Research' 1980; cf. F. M. Wuketits (1982); see, furthermore, especially E. and W. LeinfelIner (1978). 43 Cf. N. Hartmann (e.g. 1964). 44 For details see M. Eigen and R. Winkler, op. cit. 45 See R. Kaspar (1980), K. Lorenz (1973), R. Riedl (1980), F. M. Wuketits (1978b, 1981). 46 cr. L. von Bertalanffy (1967) and K. Lorenz (1961, 1973, 1974). 47 Cf. e.g. B. Rensch, op. cit., R. Riedl (1975, 1976, 1980), W. Strombach (1968), F. M. Wuketits (1978a, b; 1981), and others. 48 K. Lorenz (1973), cf. 1977 edition of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, p. 7. 49 Cf. J. von Uexkiill, op. cit. 50 See G. Vollmer, op. cit. and in this volume, pp. 69-121. 51 On this 'system of hypotheses' see R. Riedl (1980) and in the present volume, pp.40-1. 52 K. R. Popper (1959), p. 453. On hypothetical realism see, furthermore, e.g. B. Kanitscheider (1979), K. Lorenz, op. cit., R. Riedl,op. cit., and G. Vollmer, op. cit. 53 H. Albert (1978), p. 215. 54 Ibid. 55 J. Piaget (1973), p. 32. On the interdependence of general psychology and the evolutionary perspective, see also e.g. M. H. Bickhard (1979). 56 See Piaget's book of the same title (1970) and e.g. his Biologie et connaissance (1967). 57 A recent discussion of this problem is B. BlaZek (1979). 58 For a brilliant presentation of the biological aspects of language see E. Lenneberg, op. cit. 59 C. D Hockett (1960), p. 96. 60 Ibid., p. 91 (italics not in the original text). For more details see especially E. Lenneberg, op. cit. 61 Cf. N. Chomsky, op. cit. 62 See e.g. L. von Bertalanffy's review in his General System Theory (1968). 63 See B. L. Whorf (1956). 64 When I use the term 'evolution' in a cultural context, this does not mean that I reduce culture to biological entities. What should be expressed by the concept 'cultural evolution' is the fact that cultures, like other systems, undergo changes. 6S M. 1. Herskovits, quoted after D. Bidney (1953), p. 423. (Note Bidney's critique of this view.) 66 It is worthwhile to mention here Paul Watzlawick's distinction between 'flIst-order

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 29

reality' (= physical reality) and 'second-order reality' (= reality due to cultural and/or social conventions); see P. Watzlawick (1977). On the social relativity of episternic structures see especially P. 1. Berger and T. Luckmann (1966). 67 Cf. e.g. G. Radnitzky (1981). 68 In his Anthropologie structurale (1958) and in later works. However, Levi-Strauss had already developed his structuralist view in the 1930s and 19405. 69 G. Radnitzky (1980), p. 315 (my italics). 70 See e.g. the interesting study by E. Topitsch (1979). 71 Cf. R. Riedl (1980). 72 cr. R. Riedl (1978/79) and F. M. Wuketits (1981). 73 K. Lorenz (1973), see 1977 edition of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, p. 245. 74 Ibid. 7S D. T. Campbell, op. cit., p. 451. 76 Particularly in his Objective Knowledge (1972). 77 cr. R. Kaspar (1981) and R. Riedl (1980). 78 Cf. W. Leinfellner (1980) and G. Vollmer, op. cit. 79 See E. Oeser (1976), particularly vol. II and in the present volume, pp. 154-7. Oeser's information-theoretical approach corresponds to model-theoretical accounts for epistemological problems; see e.g. H. Stachowiak (1980). 80 Cf. K. R. Popper (1972). 81 Cf. E. Oeser, op. cit. 82 It is not possible to discuss here the philosophical as well as psychological problem 'rationality vs. irrationality in the history of science' (cf. I Lakatos and A. Musgrave, op. cit.). Scientific research (discovery), certainly, often has been based upon irrational components and we must not neglect such factors as 'intuition'. But science would be rather a chaos of theories, statements, predictions, and so forth, if it were not put into a 'rational framework'. Therefore, on the whole, scientific research means (and it must mean) always a decisive step towards rationality. How else should we master the objective world and our own situation? 83 H. Mohr (1977), p. 21. 84 I do not want to withhold the critique of evolutionary epistemology from the reader, for this volume should stimulate further discussions of the problems in question. Therefore, when preparing the volume, I invited Reinhard Low to present his critical standpoint; see Low's essay, pp. 209-31.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albert, H.: 'Science and the Search for Truth', in G. Radnitzky and G. Andersson (eds.), Progress and Rationality in Science, D. Reidel, Dordrecht, 1978, pp. 203-220.

Bartley, W. W., III: 'Critical Study: The Philosophy of Karl Popper Part I: Biology and Evolutionary Epistemology' Philosophia 6 (1976),463-494.

Berger, P. 1. and Luckmann, T.: The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, Doubleday'& Co., New York, 1966.

Bergson, H.: L 'Evolution creatrice, Presses Univ. de France, Paris, 1907. (English translation: Macmillan, London, 1911.)

30 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

Bertalanffy, L. von: Robots, Men and Minds: Psychology in the Modern World, Braziller, New York, 1967.

Bertalanffy, L. von: General System Theory: Foundations, Development Applications, Braziller, New York, 1968.

Bickhard, M.H.: 'On Necessary and Specific Capabilities in Evolution and Development', Hum. Dev. 22 (1979), 217-224.

Bidney, D.: Theoretical Anthropology, Columbia University Press, New York, 1953. Blazek, B.: 'On Scope and Limits of Analogies Between Evolutionand Cognition', Proc.

Symp. Natur. Select., Prague, 1978, pp. 543-558. Blazek, B.: 'Can Epistemology as a Philosophical Discipline Develop into a Science?', Dia·

lectica 33 (1979),87-108. Brunswik, E.: '''Ratiomorphic'' Models of Perception and Thinking', Acta Psychol. 11

(1955),108-109. Bunge, M.: 'The Mind-Body Problem in an Evolutionary Perspective', Ciba Foundation

Series 69 (1979),53-63. Bunge, M.: The Mind·Body Problem: A Psychobiological Approach, Pergamon Press, Ox

ford-New York, 1980. Campbell, D.T.: 'Evolutionary Epistemology', in P. Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of Karl

Popper, Part I, Open Court, La Salle, 1973, pp. 413-463. Chomsky, N.: Language and Mind, Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., New York, 1960. Darwin, C.: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, Murray, London, 1959.

(The New American Library of World Literature Inc., New York-Toronto, 1958.) Darwin, C.: The Descent of Man, Murray, London, 1871. Eigen, M. and Winkler, R.: Das Spiel: Naturgesetze steuern den Zufall, R. Piper & Co.,

Munich-Zurich, 1975. FJaskiimper, P.: Die Wissenschaft vom Leben: Biologisch·philosophische Betrachtungen,

E. Reinhardt, Munich, 1913. Ghiselin, M.T.: The Triumph of the Darwinian Method, University of California Press,

Berkeley-Los Angeles, 1969. Gutmann, W.F. and Bonik, K.: Kritische Evolutionstheorie: Ein Beitrag zur Uberwindung

altdarwinistischer Dogmen, Gerstenberg, Hildesheim, 1981. Haeckel, E.: Die Weltriithsel: Gemeinverstiindliche Studien fiber Monistische Philosophie,

A. Kroner, Stuttgart, 1899. Hanson, N.R.: Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of

Science, Cam bridge University Press, London, 1958. Hartmann, N.: Der Au/bau der realen Welt: Grundrif3 der allgemeinen Kategorienlehre,

W. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1963. Hockett, C.D.: 'The Origin of Speech', Scient. Amer. 203 (3) (1960),88-96. Huxley, J.: New Bottles for New Wine; Essays, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1957. Huxley, T.H.: On the Origin of Species, Murray, London, 1863 (The University of Michigan

Press, Michigan, 1968.) Jantsch, E.: Design for Evolution: Self Organization and Planning in the Life of Human

Systems, Braziller, New York, 1975. Kanitscheider, B.: Philosophie und moderne Physik: Systeme - Strukturen - Synthesen,

Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1979. Kant. I.: Kritik der rein en Vernunft, Hartknoch, Riga, 1781. (English translation: Macmil

lan, London, 1929.)

A CHALLENGE TO SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHY 31

Kaspar, R.: 'Die Evolution erkenntnisgewinnender Mechanismen', Bi%gie in unserer Zeit 10 (1980), 17-22.

Kaspar, R.: 'Die Evolution des Erkennens: Geschichte, Grundlagen und Konsequenzen der evolutioniiren Erkenntnistheorie', in G. -K. Kaltenbrunner (ed.), Wir sind Evolu· tion: Die kopemikanische Wende der Biologie, Herder, Freiburg-Basel-Vienna, 1981, pp.57-77.

Kuhn, T. S.: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1962.

Lakatos, I. and Musgrave, A. (eds.): Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Cambridge University Press, London-New York, 1970.

Leinfellner, W.: Einfohrung in die Erkenntnis· und Wissenschaftstheorie 3 , Bibliographisches lnstitut, Mannheim-Vienna-Ztirich, 1980.

Leinfellner, E. and Leinfellner, W.: Ontologie, Systemtheorie und Semantik, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 1970.

Lenneberg, E.: Biological Foundations of Language, Wiley & Sons, New York, 1967. Levi-Strauss, C.: Anthropologie structurale, Libraire PIon, Paiis, 1958. Lorenz, K.: 'Kants Lehre vom Apriorischen im Lichte gegenwiirtiger Biologie', Bliitter

forDeutschePhilosphie 15 (1941), 94-125. Lorenz, K.: 'Phylogenetische Anpassung und adaptive Modifikation des Verhaltens',

Zeitschrift for Tierpsychologie 18 (1961), 139-187. Lorenz, K.: Evolution and Modification of Behavior: A Critical Examination of the

Concepts of the "Learned" and the "Innate" Elements of Behavior, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago-London, 1965;

Lorenz, K.: Die Riickseite des Spiegels: Versuch einer Naturgeschichte menschlichen Erkennens, R. Piper & Co., Munich-Ziirich, 1973. (English translation: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York-London, 1977.)

Lorenz, K.: 'Analogy as a Source of Knowledge', Science 185 (1974),229-234. Mohr, H.: Wissenschaft und menschliche Existenz: Vorlesungen iiber Struktur und

Bedeutungder Wissenschaft, Rombach, Freiburg, 1967. Mohr, H.: Lectures on Structure and Significance of Science, Springer, Berlin-Heidel

berg-New York, 1977. Monod, J.: Le hasard et la necessite, Editions du Seuil, Paris, 1970. (English translation:

Knopf, New York, 1971.) Oeser, E.: Wissenschaft und Information, 3 vols., Oldenbourg, Vienna-Munich, 1976. Piaget, J.: Biologie et connaissance, Gallimard, Paris, 1967. Piaget, J.: Genetic Epistemology, Columbia University Press, London-New York, 1970. Piaget, J.: Main Trends in Psychology, G. Allen & Unwin, London, 1973. Popper, K. R.: The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1959. Popper, K. R.: Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge,

Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1969. Popper, K. R.: Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, Clarendon Press,

Oxford, 1972. Popper, K. R.: Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography, W. Collins, Sons & Co.,

Glasgow, 1976. Popper, K. R. and Eccles, J. C.: The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism,

Springer International, New York-London-Heidelberg-Berlin, 1977. Radnitzky, G.: 'Contemporary Changes in our Image of Man and their Historical Roots',

32 FRANZ M. WUKETITS

Proceedings of the VIIIth International Conference on the Unity of the Sciences 1979, International Cultural Foundation Press, vol. I, New York, 1980, pp. 308-317.

Radnitzky, G.: The Complementarity of Western and Oriental Philosophy', Social Science 56 (1981), 82-87.

Rensch, B.: Biophilosophie auf erkenntnistheoretischer Grundlage (Panpsychistischer Identismus), G. Fischer, Stuttgart, 1968. (English translation: Columbia University Press, New York-london, 1971.)

Rensch, B.: Das universale Weltbild: Evolution und Naturphilosophie, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt/M., 1977.

Riedl, R.: Die Ordnung des Lebendigen: Systembedingungen der Evolution, P. Parey, Hamburg-Berlin, 1975. (English translation: Wiley & Sons, New York, 1979.)

Riedl, R.: Die Strategie der Genesis: Naturgeschichte der realen Welt, R. Piper & Co., Munich-Ziirich, 1976.

Riedl, R.: 'A Systems-analytical Approach to Macro-evolutionary Phenomena', The Quart. Rev. of Bioi. 52 (1977), 351-370.

Riedl, R.: 'tiber die Biologie des Ursachen-Denkens. Ein evolutionistischer, systemtheoretischer Versuch', Mannheimer Forum 78/79 (1978/79), 9-70.

Riedl, R.: Biologie der Erkenntnis: Die stammesgeschichtlichen Grundlagen der Vernunft (with the collaboration of R. Kaspar), P. Parey, Berlin-Hamburg, 1980.

Roederer, 1. G.: 'Human Brain Functions and the Foundations of Science', Endeavour (New Series) 3 (1979),99-103.

Simpson, G. G.: This View of Life: The World of an Evolutionist. Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., New York, 1963.