WP005-03 Wang Ahmed

-

Upload

maniqueabeyratne -

Category

Documents

-

view

38 -

download

0

description

Transcript of WP005-03 Wang Ahmed

-

Managing knowledge workers

By Catherine L Wang & Pervaiz K Ahmed Working Paper Series 2003

Number WP005/03

ISSN Number 1363-6839 Catherine L Wang Research Assistant University of Wolverhampton, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1902 321651 Email: [email protected] Professor Pervaiz K Ahmed Chair in Management University of Wolverhampton, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1902 323921 Email: [email protected]

-

Managing knowledge workers

Copyright University of Wolverhampton 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, photocopied, recorded, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The Management Research Centre is the co-ordinating centre for research activity within Wolverhampton University Business School. This working paper series provides a forum for dissemination and discussion of research in progress within the School. For further information contact:

Management Research Centre Wolverhampton University Business School

Telford, Shropshire TF2 9NT 01902 321772 Fax 01902 321777

2

-

Managing knowledge workers

Abstract In the knowledge economy, the workplace is featured by an increasing number of knowledge workers. An imperative organisational task is to improve knowledge workers productivity. To attain this goal, human resource management is facing two prime challenges: how to motivate knowledge workers as individuals, and how to manage knowledge workers in the strategic context of the organisation. This paper first proposes an AI Model, which elaborates specific needs and characteristics of knowledge workers and identifies the motivational factors. This paper then discusses that managing knowledge workers must be set in the organisational contexts, and be aligned with knowledge management strategies in order to attain higher organisational performance. The paper is theoretically based, but has practical implications on the strategic role of human resource management in the knowledge era.

3

-

Managing knowledge workers

The authors

Catherine L Wang Catherine Wang is a Research Assistant at Wolverhampton Business School. Her research interests include knowledge management, organisational learning and, quality and innovation management. She has previously worked in industry and consultancy in the area of international business.

Professor Pervaiz K Ahmed Professor Pervaiz K Ahmed, is Head of Japanese Management Research Unit, and the Centre for Enterprise Excellence, both at Wolverhampton Business School. He has published over 100 papers in international journals and has been a keynote speaker at a number of prestigious conferences. Pervaiz is currently editor of the European Journal of Innovation Management and was formerly editor of the Business Process Management Journal from 1996-2000. Until 2000 he co-edited the International Journal of Benchmarking, Quality Focus and Journal of Management in Medicine, and currently serves on the editorial advisory board of numerous international journals. Being active in the European Foundation for Quality Management he has served as a panel member for academic awards for four years and has worked with many blue chip companies, for example, Eida Faberge, Lever Europe, Birds Eye Walls, Van den Berg Foods, AT&T etc.

4

-

Managing knowledge workers

Managing knowledge workers

Introduction Peter Druckers (1992 p. 10) comment on knowledge worker productivity is well quoted. Knowledge workers cannot be supervised effectively. Unless they know more about their speciality than anybody else in the organisation, they are basically useless. This remains the mindset of some managers in the business world. While a growing number of employers covet the contributions of knowledge workers, few know how to monitor and improve their performance (Amar, 2002). The lack of understanding of their characteristics, needs and motivations leads to the fact that many managers still treat knowledge workers as an exceptional category of employees. Managing knowledge workers becomes a new challenge. In the face of this challenge, the role of human resource management needs to be adapted. Several human resource management models have been developed accordingly (De Geus, 1997; Currie, 1998; McCracken & Wallace, 2000; Wills, 1997), analysing the reasons of investment in human resource development (Garavan et al 2001). In the knowledge era, the challenges for human resource management are primarily twofold: how to link human resource management to knowledge management strategies, which are intrinsically associated to overall corporate strategies; and how to motivate knowledge workers as individuals and improve their productivity. The two tasks are imperative for organisational success, and indeed primary challenges for strategic human resource management in the 21st Century. The paper proposes an AI Model for identifying characteristics and motivational factors of knowledge workers, and then embraces managing knowledge workers in the strategic context of the organisation.

Knowledge workers Historically, knowledge work was the province of intellectuals, who were dissociated from private enterprises (Despres & Hiltrop, 1995). Intellectual workers enrich human knowledge both as creators and as researchers; they apply it as practitioners, they spread it as teachers, and they share it with others as experts or advisers. They produce judgements, reasonings, theories, findings, conclusions, advice, arguments for and against, and so on. (Cuvillier, 1974, p. 293). The 20th Century witnessed the transformation of the nature of the workplace, which is featured by the complexity and variety of tasks, the reproducibility of expertise, the creative undertakings, and the intensive training and development required (Scarbrough, 1993). The workplace has emerged with knowledge work and the trend is that knowledge work will comprise the majority of tasks by the end of the 21st Century. Knowledge work is defined as systematic activity that traffics in data, manipulates information and develops knowledge. The work may be theoretical and directed at no immediate practical purpose, or pragmatic and aimed at devising new applications, devices, products or processes. On an abstract level, however, it is less obvious that the knowledge thus produced becomes an assembled set of specialised information which: responds to needs and problems, frequently defining these by its existence; functions in a context to reduce ambiguity and inject a sense of order, progress or direction; and has the self-referential quality of legitimising those who claim to hold it, thus making rhetoric and impression management crucial. (Despres & Hiltrop, 1995, p. 12). The definitions of knowledge workers are multiple. One stream of research clearly distinguishes knowledge workers. For example, Amar (2002) considers knowledge workers as a new kind of employees paid not to create, produce or manage a tangible product or service, but rather to gather, develop, process and apply information. However, this is debatable. Firstly, in the real world the process of knowledge production is not always dissociated from the tangible production. Secondly, all workers to some extent process and apply information. These indeed make it very difficult to draw a clear line between knowledge workers and traditional workers. Consequently, these arguments lead

5

-

Managing knowledge workers

to another stream of research, which advocates that all workers are knowledge workers, and recognises that each type of work contains some level of knowledge processing and application. However, the latter view undermines the specific characteristics of knowledge workers, and leads to an all-inclusive solution to managing workers. Instead, this paper proposes that the characteristics of knowledge workers and traditional workers move along a spectrum (as indicated in Figure 1) in many aspects, such as employment orientation, career formation, expertise association, skills and knowledge, learning orientation, the nature of work, and performance outcomes, etc. The more knowledge content the work involves, the more intensive characteristics of knowledge workers are demonstrated. Likewise, the less knowledge content the work involves, the more intensive characteristics of traditional workers are demonstrated. A typified knowledge worker seeks employability and lifelong learning rather than lifelong employment, develops a career through education, experience, and socialisation, associates more to professions, networks and peers rather than the company, possesses specialised and deep knowledge rather than narrow and functional knowledge and skills, are more intrinsically motivated by challenging tasks and recognition than simply financial incentives, and contribute to major innovations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Characteristics of knowledge workers and traditional workers

Traditional workersKnowledge workers

Employment orientation

Career formation

Expertise association

Skills and knowledge

Learning orientation

Nature of work

Reward & motivation

Performance outcomes

Seeking employability & career self-reliance

External to the organisation via education, experience, socialisation

Associated to professions, networks, peers

Specialised & deep, with diffuse peripheral focuses

Seeking lifelong learning to strengthen professional competence

Creativity, complexity, variety, challenging

More intrinsically motivated, prone to recognition related reward

Irregular, major contributions over a longer term

Seeking lifelong employment & job security

Internal to the organisation via training & development

Associated to the organisation & its career systems

Narrow and functional knowledge and skills

Requiring training & development relevant to better job performance

Routine, well-defined, repetitive, simplified tasks

More extrinsically motivated, prone to financial incentives

Regular, dependable, small contributions over a short term

Criteria

The different features of knowledge workers require companies to motivate, monitor and evaluate knowledge workers in a different way from traditional workers. For HRM, the primary challenge at their operational level is to motivate knowledge workers to improve their performance. As shown in Figure 1, knowledge workers are self-managing, which makes most of the traditional motivation theories less relevant to current HR practice.

Motivating knowledge workers Early motivation theories discern factors that energize, direct, sustain, or prohibit individual behaviour through analysing individual needs. Such theories are Maslows (1954) hierarchy of needs theory, McGregors (1960) Theory X and Theory Y, Alderfers (1972) ERG theory, McClellands (1962) socially acquired needs theory, and Herzbergs (1959) two factor theory. Mitchell (1982) calls the above as theories of arousal. However, these need-based approaches that focus on individual differences have been overwhelmed by information processing or social-environmental approaches to motivations (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). The latter are represented by the goal setting theory (Locke, 1968), the expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964), the operant conditioning theory (Skinner, 1954), and the equity theory (Adam, 1963). Mitchell (1982) names these latter theories as theories of choices. The main postulates and conditions for practical use are briefly indicated in Table 1.

Table 1. A summary of the main traditional motivation theories

6

-

Managing knowledge workers

Theories of arousal Theories of choices

Main theories 1. The hierarchy of needs theory (Maslow, 1954) 2. The Theory X and Theory Y (McGregor, 1960) 3. The ERG theory (Alderfer, 1972) 4. The socially acquired needs theory

(McClelland, 1962) 5. The two factor theory (Herzberg, 1959)

1. The goal setting theory (Locke, 1968) 2. The expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964) 3. The operant conditioning theory (Skinner,

1954) 4. The equity theory (Adam, 1963)

Main postulates The arousal process is due to need deficiencies, for which people will work to fulfil

Different people are motivated by different things (except that Maslow reckoned each individual has the same set of needs in the same order)

The upper level needs are generally overlooked and should be attended with efforts

Social expectations have powerful effects on motivation

Current information is extremely important (Mitchell, 1982)

They all define motivation as an individual, intentional process

All (except the operant approach) focus on relatively current information

All define motivation as directly influenced by outcomes (except that the goal setting sees outcomes as indirectly influencing innovation through goal level and intentions)

Causes of behaviour are different: (1) intentions to reach a goal, (2) expectations of maximum payoff, (3) past reinforcement histories (4) a desire for fairness

Conditions for use The whole set of organisational factors makes it difficult to individualise rewards and emphasise upper level intrinsic needs

Greater flexibility in compensation is required Influencing social norms is more difficult. A

solution is to match the level of appraisal with those people who most frequently observe the work of the individual

Many jobs involve considerable interdependence and make it difficult to specify individual contributions. Group goals or rewards may be used

Jobs that observations do not reach are difficult to implement individual feedback and reward

Changes in jobs and people necessitate changes in motivation systems

The heterogeneity of jobs causes difficult for individual feedback and reward

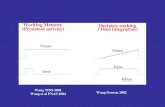

Sources: Mitchell (1982) Through extensive literature review, Mitchell (1982) notes that one of the needs for furthering motivation theories is the development and test of contingency type models of motivation. The task for this is not whether existing theories work, but where and when they work best. This, together with other theoretical development tasks, requires researchers to re-examine the fundamentals of these theories, i.e. the needs and characteristics of individuals, and the contexts of tasks and environments. Failing to study these underlying principles are likely to undermine the motivation systems, or even trigger the de-motivation factors, if the factors that hinder the application of the motivational theory have not been articulated effectively. For example, the well known crowding-out-effect. When external incentives are perceived to be controlling by the individual affected, intrinsic motivation tends to be undermined (Frey, 1997; Lepper & Greene, 1978; Lazear, 1996). To be more specific, individuals work morale may be reduced when they receive monetary rewards that are contingent on their performance. This is especially the case in motivating knowledge workers, whose nature of work, skills levels, and domestic and material circumstances etc. are different (Hunt, 1992). Successful companies will be those who can motivate their knowledge workers to their full talents for the company (Bower, 1994), whilst resolving the problem of retaining a certain managerial control and allowing creativity and operational autonomy simultaneously (Bailyn, 1985). To attain this goal, specific characteristics of knowledge workers must be identified and the factors that influence their productive behaviours must be examined. This paper identifies that knowledge workers in general are intrapreneurial, individualistic, intuitive, involved, inquisitive and informal. Six motivators are also identified accordingly: accountability, advancement, affirmation, association, attraction and autonomy. These characteristics and motivators form the AI Model (see Figure 2).

Knowledge workers are highly individualistic in terms of giving priority to their personal growth. Companies need to provide opportunities for their career advancement

7

-

Managing knowledge workers

Knowledge workers place a greater priority on individual goals than group goals (Amar, 2002). They seek intellectual, personal and professional growth, and are very keen to the opportunities to realise their potential (Tampoe, 1993) and development and maintenance of personal reputation in the community (Markus, et al 2000). The acquisition of generic competencies is given particular attention, as a prerequisite to attain their career goals (Garavan et al 2001). London Universitys survey of graduates found that over 90 percent expected their employer to help their development (Prickett 1998). One-third of high-fliers surveyed by Holbeche (1998) would leave if their employers could not broaden their skills. Individuals value considerably the investments that companies make in their intellectual enhancement. To motivate and retain knowledge workers, companies need to provide continuous training and career advancement opportunities (Amar, 2002; Drucker, 1999), and align their company tasks with their personal development goals.

Knowledge workers are informal. Operational autonomy is crucial for knowledge workers to extend their intellects Knowledge workers are self-managing in their professional conducts (Markus et al 2000), thus require full control over their work environment (Amar, 2002). Motivating knowledge workers lies in drawing on their inner drive and motivation, rather than in better methods of supervision (Tampoe, 1993). Instead of exerting control over them, managers should direct knowledge workers as if they were unpaid volunteers, tied to the company by commitment to its aims and purposes and often expecting to participate in its governance (Drucker, 1998). Markus, et als (2000) research on knowledge workers of open-source projects found that membership of the project group is fluid, maintaining a stable core of participants while capitalizing on the temporary efforts of numerous volunteers. In these projects, control is maintained through autonomous decision makers following a few simple rules, and the self-governance is achieved both formally through discussion and voting and informally through social control. Operational autonomy ranks second in motivational factors identified in Tampoe (1993), next to the personal growth factor. Companies need to continuously update their policies, structures and systems in the way that helps employees to achieve their full potential and to contribute their best to the companies.

Knowledge workers are intrapreneurial. Accountability is an effective motivator for them to work on their own initiatives and achieve tasks Knowledge workers are individuals who while remaining within a company use their entrepreneurial skills to develop new products or lines of business. They are self-managing, work on their own initiatives, and are responsible for their own contribution (Drucker, 1999). Companies should allow knowledge workers to be held accountable for their own operations, including quality, time and cost, etc. Accountability is also related to task achievement of producing work to a standard and quality, which the knowledge worker can be proud of (Tampoe, 1993). Some authors describe the relationship between knowledge workers and the employing company as partnership. A knowledge worker is responsible for his own work, learning and career, as well as contributions to the company.

Knowledge workers are highly involved in their professional tasks. Companies need to strengthen their association and identification as a member of the company, and a member of their professional society Knowledge workers need to identify their job and believe in the importance of work. The extent of this identification is job involvement (Page, 1998), which is imperative for motivating knowledge workers. The role of organisational identification in motivating knowledge workers is twofold: knowledge workers with a cosmopolitan orientation, such as scientists, have a greater focus on their professional peer group than their employing company. In contrast, knowledge workers with a local orientation, such as engineers, primarily identify with their employing company and its goals and hierarchy (Page, 1998). One thing is for sure: if companies want to increase knowledge worker productivity, they need to associate their professional undertakings to company development tasks, and enhance knowledge workers identification in the company.

Knowledge workers are inquisitive. They are more likely motivated by challenging tasks that attract their personal interest

8

-

Managing knowledge workers

Knowledge workers are highly inquisitive. They seek variety, relevancy, stimulation and constant changes (Bogdanowicz & Bailey, 2002). To motivate knowledge workers, the tasks should be highly interesting and challenging to them. To keep knowledge workers interested, continuous innovation has to be built into the knowledge workers job (Drucker, 1999). Knowledge workers and companies need to create mutual attraction. Knowledge workers bring in unique knowledge and skills that are attractive to the company, while the company need to provide an attractive environment that helps knowledge workers to find their passion and work on the type of work that appeals to their own curiosity and interest.

Knowledge workers are highly intuitive. Companies need to develop performance systems that effectively measure their productivity and affirm their contributions over a longer time Traditional workers focus on completing a task which has been well defined and allocated to them. Whilst the nature of knowledge work is complex, ill-defined, and requires a higher degree of creativity. In knowledge work, the task does not program the worker. Instead, the first step to undertake a task is to define the task (Drucker, 1999). The creative nature of tasks defines the unconventional, non-routine, even destructive process of conducting the task and solving the problem. In many cases, managers find their behaviour irregular and difficult to measure their performance in a short term. However, they make major contributions to the company and define the long-term strategic position in the marketplace. A main challenge for management is to devise systems to provide justified evaluation and feedback to knowledge workers. Measuring knowledge worker productivity is a part of a long process, and it is hard to gauge its effectiveness until a product or process is concluded (Amar, 2002). An effective performance and feedback system is crucial, since appreciation of their creative undertakings and affirmation of their achievement are effective motivators. On the contrary, conventional judgement of their short-term performance can be detrimental since knowledge workers may be de-motivated by bureaucracy and unnecessary routines.

KnowledgeWorkers

Intra

pren

euria

lIndividualistic

Intuitive Inquisitive

Invo

lved Informal

Advancement Accountability

Affirmation Attraction

AutonomyAssociation

Figure 2. The A1 Model These characteristics of knowledge workers are interrelated (see Figure 2). Each knowledge worker may give priority to different factors identified in the AI model. Theoretically, management should endeavour to understand each individuals specific needs and devise reward and motivation methods. However, practically, it is difficult to reward and motivate each one on an individual basis. The solution here lies in designing a motivation and reward system based on these generic characteristics

9

-

Managing knowledge workers

and needs of knowledge workers, simultaneously allowing flexibility and free choices within the reward system. Another aspect that is worth mentioning is that these above needs and motivators belong to a higher level of motivational factors, which are more intrinsically related. Those lower level motivation factors such as financial reward and security etc are not excluded from motivational factors of knowledge workers. But these lower level motivators must be systematically considered and used only when they are positively related to this higher level factors or intrinsic motivators, avoiding the crowding-out-effect. For this purpose, the traditional motivation theories as summarised in Table 1 provide multi-perspective analysis and guidance.

Managing knowledge workers in the strategic context The above section analyses the motivational needs of knowledge workers. However, from the organisational perspective, the purpose of motivating knowledge workers is to increase their productivity and contributions to organisational success. Then the question becomes - Does motivation really make a difference for organisational performance? An answer made out of common observations is: performance is not the same as motivation. Researchers such as Porter and Lawler (1968) and Campbell and Pritchard (1976) encompass several elements in the formula of performance outcomes. In general, to improve performance, one must (1) know what is required for the job role, (2) have the ability to do what is required, (3) be motivated to do what is required, and (4) work in an environment in which intended actions can be translated into behaviour (Mitchell, 1982, p83). When analysing knowledge workers performance, the assumption is that knowledge workers have the ability to do what is required, because they are highly intellectual and skilled. This eliminates the second concern indicated above. The previous section of this paper intends to identify the motivational needs of knowledge workers, which are the third element of the performance formula. Therefore, if knowledge workers are effectively motivated, the puzzle of knowledge workers performance indeed leaves to the other two elements, which are if the job role is communicated clearly to knowledge workers, and if the organisation is able to implement those creative outcomes into tangible outputs. These require managing knowledge workers in the strategic contexts of the company. Indeed, questions such as how to structure the company, how to make the transition to new organisational forms, how to align managing knowledge workers to corporate strategies, and how to obtain output and productivity from an increasingly knowledgeable workforce constitute a main stream of challenges to the current HRM (Despres & Hiltrop, 1995; Soliman & Spooner, 2000) The best practice approach has propagated a recipe of successful knowledge management, which discerns several critical factors. The approach prescribes a universally applicable knowledge management through factors such as managing employee commitment (Wood, 1995). Whilst it is currently well known that the best practice from one company does not necessarily work in another one, because the contexts are different in each company. In contrast, the congruent approach suggests that HRM needs to be aligned with knowledge management practice, and both need to be congruent with the overarching corporate strategy. The danger of mismatch has been warned by several authors. For instance, Carter and Mueller (2001, p218) highlight the complex dialectical relationship that exists within knowledge organisations between the creation of knowledge and the appropriation of knowledge. In their study of a head hunting organisation, they demonstrate the way in which HRM practice that was implemented in an attempt to make the organisation more efficient actually resulted in a diaspora of knowledge workers, an event that was to threaten the very existence of the organisation itself. Broadly speaking, there are two generic types of knowledge management strategies: the codification strategy and the personalisation strategy (Hansen et al 1999), each calling for different HR practices. In the codification model, managers need to develop a system that encourages people to write down what they know and to get those documents into the electronic repository companies that are following the personalisation approach need to reward people for sharing knowledge directly with other people (Hansen et al 1999, p113). Table 2 briefly introduces recommendations of HR practice under the two knowledge management strategies respectively.

10

-

Managing knowledge workers

Table 2. KM strategies and HRM practices

Codification strategy Personalisation strategy

Recruitment & selection Hire new college graduates who are well suited to the reuse of knowledge and the implementation of solutions

Hire MBAs who like problem-solving and can tolerate ambiguity

Training & development Train people in groups and through computer-based distance learning

Train people through one-to-one mentoring

Reward system Reward people for using and contributing to document database

Reward people for directly sharing knowledge with others

Source: Adapted from Hansen et al (1999) In brief, HRM has evolved dramatically over the centuries: from personnel administration handling employee selection, training, compensation, grievances, discharges, and safety, etc. in the early 1900s, to the emergence of the human relations movement emphasising employee communications, cooperation and involvement, and to the greater challenges of managing knowledge workers. HRM is not only responsible for motivating people, and helping companies navigate a maze of regulations, executive orders and court decisions. Its role has already started to extend beyond the domain of HR departments, into long-range strategic planning, responsible for optimising employee skills, matching people to jobs and maximizing the potential of employees as valuable assets, strategic outsourcing, etc. (Raich, 2002).

Conclusions The role of HRM in attaining knowledge management success has been widely recognised. From strategic HR planning, to recruiting and selecting of people, to motivating employees, and to measuring employee performance, etc. HRM is intrinsically inter-twined with all aspects of organisational management. Its strategic role has received increasing consideration accompanied by the rising recognition of intellectual capital and knowledge asset, which is embedded in peoples mind, behaviour and perception. In fact, some companies have recognised that knowledge management must be led by HR teams in order to achieve success. This is a lesson learnt from the failure of IT driven knowledge management approach. Knowledge management provides opportunities as well as challenges to HRM. Managing knowledge worker productivity has become an ever so important task. Any deficiency in their performance is less likely related to their ability and skills, but their willingness to contribute to organisational tasks. Whilst their willingness is not necessarily associated to payment and financial reward. The critical role of HRM is to examine their specific needs and characteristics and identify the motivational factors. This paper has dovetailed the area by proposing an AI Model. Another task, perhaps more challenging, is that HRM must undertake the strategic role and create the match between HRM, corporate strategies and knowledge management, as well as aligning other organisational parameters to the requirements of improving knowledge worker productivity.

11

-

Managing knowledge workers

References Adam, J. S. (1963) Toward an understanding of equity Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology

67(November) pp. 422-436.

Alderfer, C. P. (1972) Existence, relatedness and growth: human needs in organisational setting (New York, Free Press).

Amar, A. D. (2002) Managing knowledge workers: unleashing innovation and productivity (Westport, CT; London: Quorum Books).

Bailyn, L. (1985) Autonomy in the industrial R & D lab Human Resource Management 24(2) pp. 129-146.

Bogdanowicz, M. S. & Bailey, E. K. (2002) The value of knowledge and the values of the new knowledge worker: generation X in the new economy Journal of European Industrial Training 26(2/3/4) pp. 125-129.

Bower, D. G. (1994) Unleashing the potential of people Journal of European Industrial Training 18(7) pp. 30-36.

Campbell, J. P. & Pritchard, R. D. (1976) Motivation theory in industrial and organisational psychology, In: M. D. Dunnette (Ed) Handbook of industrial and organisational psychology (Chicago: Rand McNally) pp. 62-130.

Carter, C. & Mueller, F. (2001) The dialectics of organisational knowledge: the duality of appropriation and creation Discussion Papers 01/ 04, University of Leicester Management Centre, Leicester, UK.

Carter, C. & Scarbrough, H. (2001) Towards a second generation of KM? Education + Training 43(4/5) pp. 215-224.

Cuvillier, R. (1974) Intellectual workers and their work in social theory and practice International Labor Review 109(4) pp. 291-317.

Despres, C. & Hiltrop, J. (1995) Human resource management in the knowledge age: current practice and perspectives on the future Employee Relations 17(1) pp. 9-23.

Drucker, P. (1992) The new society of organisations Harvard Business Review 70(5) pp. 95-104.

Drucker, P. (1997) Innovation and entrepreneurship (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann).

Drucker, P. (1999) Knowledge-worker productivity: the biggest challenge California Management Review 41(2) pp. 79-94.

Drucker, P. F. (1998) Managements new paradigms Forbes October 5th pp. 152-177.

Frey, B. S. (1997) Not just for the money: an economic theory of personal motivation (Cheltenham, UK and Brookfield, USA: Edward Elgar).

Garavan, T. N., Morley, M., Gunnigle, P. & Collins, E. (2001) Human capital accumulation: the role of human resource development Journal of European Industrial Training 25(2/3/4) pp. 48-68.

Hansen, M. T., Nohria, N. & Tierney, T. (1999) Whats your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review 77(2) pp. 106-116.

Herzberg, F. B. (1959) The motivation to work (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

Holbeche, L. (1998) High flyers and succession planning in changing organisations (Roffey Park Management Institute).

Hunt, J. W. (1992) Managing people at work 3rd Edition (New York: McGraw Hill).

Lazear, E. P. (1996) Personnel economics: past lessons and future directions Journal of Labor Economics 17 pp. 199-236.

12

-

Managing knowledge workers

Lepper, M. R. & Greene, D. (Eds) (1978) The hidden costs of reward: new perspectives on the psychology of human motivation (Hillsdale, NY: Erlbaum).

Locke, E. A. (1968) Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives Organisational Behavior and Human Performance 3(May) pp. 157-189.

Markus, M. L., Manville, B. & Agres, C. E. (2000) What makes a virtual organisation work? Sloan Management Review 42(1) pp. 13-26.

Marx, L. & Smith, M. R. (1994) Does technology drive history? (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Maslow, A. H. (1954) Motivation and personality (New York: Harper).

McClelland, D. C. (1962) Business drive and national achievements Harvard Business Review 40(4) pp. 99-112.

McCracken, M. & Wallace, M. (2000) Towards a redefinition of strategic HRD Journal of European Industrial Training 24(5) pp. 281-290.

McGregor, D. (1960) The human side of enterprise (New York: McGraw-Hill).

McGregor, E. B., Jr. (1991) Strategic management of human knowledge, skills, and abilities (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Mitchell, T. R. (1982) Motivation: new directions for theory, research, and practice Academy of Management Review 7(1) pp. 80-88.

Page, D. (1998) Predicting the job performance of scientists and engineers Academy of Management Executive May pp. 98-99.

Porter, L. W. & Lawler, E. E. III (1968) Managerial attitudes and performance (Homewood, ILL: Dorsey).

Prickett, R. (1998) Firms complain of quality shortfall among students People Management 9(July) pp. 10.

Raich, M. (2002) HRM in the knowledge-based economy: is there an afterlife? Journal of European Industrial Training 26(6) pp. 269-273.

Salancik, G. R. & Pfeffer, J. (1978) A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design Administrative Science Quarterly 23 pp. 224-253.

Scarbrough, H. (1993) Problem-solutions in the management of information systems expertise Journal of Management Studies 30(6) pp. 939-955.

Skinner, B.F. (1954) The science of learning and the art of teaching Harvard Educational Review 2(2) pp. 86-97.

Soliman, F. & Spooner, K. (2000) Strategies for implementing knowledge management: role of human resources management Journal of Knowledge Management 4(4) pp. 337-345.

Tampoe, M. (1993) Motivating knowledge workers: the challenge for the 1990s Long Range Planning 26(3) pp. 49-55.

Vroom, V. H. (1964) Work and motivation (New York: Wiley).

Wills, J. (1997) Can Do Better Personnel Today 5(June) pp. 31-34.

Wood, S. (1995) The four pillars of HRM: are they connected? Human Resource Management Journal 5(5) pp. 48-58.

Yahya, S. & Goh, W. K. (2002) Managing human resources toward achieving knowledge management Journal of Knowledge Management 6(5) pp. 457-468.

Zuboff, S. (1988) In the age of smart machine (New York: Basic Books).

13

-

Managing knowledge workers

Working Papers Series - previously published 2003

14

-

Managing knowledge workers

WP001/03 Factors affecting the size of the awareness, consideration and choice sets: a study of UK undergraduate students choosing a university

P Dawes & J Brown

WP002/03 Virtual team experiments in the Civil Service and a charity: Institutional Development (ID) through internal consultancies using Provisional Theory (PT)

B Jones, G Baldridge & L Worrall

WP003/03 Innovation, knowledge management and learning: a case study of GKN C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP004/03 Knowledge management orientation and organisational performance C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP005/03 Managing knowledge workers C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP006/03 Organisational memory, knowledge sharing, learning and innovation: an integrated model C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP007/03 Normalising the effects of management of change B Jones, L Worrall & C L Cooper

WP008/03 Gender and feminine identities: women as managers in a UK academic institution V Priola

WP009/03 Using scenarios to challenge management thinking A Wright

2002 WP001/02 Tapping into the softness of soft systems C L Wang

WP002/02 The development of womens involvement in small unionism: from cheerleaders to players? S Sayce, A-M Green & P Ackers

WP003/02 Pass the baton with the family - a case study on succession issues Y Wang

WP004/02 A review of the concept of organisation learning C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP005/02 Towards a universalistic model of leadership: a comparative study of British and American empirically derived criteria of managerial and leadership effectiveness

B Hamlin

WP006/02 Towards a generic theory of managerial effectiveness: a meta-analysis from organisations within the UK public sector B Hamlin

WP007/02 The impact of organisational change on the experiences and perceptions of UK managers from 1997-2000 L Worrall & C L Cooper

WP008/02 The informal structure: hidden energies within the organisation C L Wang & P K Ahmed

2001 WP001/01 Epistemological boundaries and methodological confusions in postmodern consumer research Rosemary Stredwick

WP002/01 Managing the balance L Worrall & C L Cooper

WP003/01 In search of Russian culture: the interplay of organisational, environmental and cultural factors in Russian-Western partnerships

Kate Gilbert

WP004/01 In support of evidence-based management within healthcare and other public sector organisations B Hamlin

WP005/01 Empowerment in manufacturing companies: a pre-condition for effective organisational learning H Shipton, J Dawson, M West & M Patterson

WP006/01 The contribution of higher education to the development of entrepreneurship: the Wolverhampton Business School experience

A Evans & R Jones

WP007/01 The role of learning and creativity in the quality and innovation process C L Wang & P K Ahmed

WP008/01 Size matters: an empirical study in the use of IT by small and large legal firms K Broome & G Singh

WP009/01 Relationships between marketing and sales: the role of power and influence P Dawes & G Massey

WP010/01 A model of the effects of technical consultants on organisational learning in high technology purchase situations P Dawes

2000 WP001/00 The Psychological effects of downsizing and privatisation F Campbell, L Worrall & C L

Cooper

WP002/00 Football managers as a metaphor for corporate entrepreneurship? B Perry

WP003/00 Dance culture and consumer behaviour: can marketers learn lessons from the rave generations C Goulding

WP004/00 Interpretation of groupware effect in an organisation using structuration theory J Hassall

WP005/00 Heritage consumption, identity formation and interpretation of the past within post war Croatia Dino Domic

WP006/00 History, identity and social conflict: consuming heritage in the former Yugoslavia Dino Domic

WP007/00 Learning in manufacturing organisations: what factors predict effectiveness? H Shipton, J Dawson, M West & M Patterson

WP008/00 Towards an understanding of business start ups through diagnostic finger printing I McPhee

WP009/00 Investigation of perspectives held by information systems development teams G Singh

1999 WP001/99 Survivors of redundancy: a justice perspective F Campbell

WP002/99 Business advice to fast growth small firms K Mole

WP003/99 Intelligent local governance: a developing agenda L Worrall

WP004/99 Curriculum planning with 'learning outcomes': a theoretical perspective B Kemp

WP005/99 Has the Russian consumers' attitude changed in recent years? V Sullivan & I Adamson

WP006/99 Grounded theory: some reflections on paradigm, procedures and misconceptions C Goulding

WP007/99 There is power in the union: negotiating the employment relationship at two manufacturing plants A-M Greene, P Ackers & J Black

WP008/99 Management skills development: the current position and the future agenda L Worrall & C Cooper

WP009/99 Marketing the capabilities in SME's in the West Midlands C Cooper & R Harris

WP010/99 Approaches to management development: the domain of information management T Bate

WP011/99 Methods of analysing ordinal/interval questionnaire data with A1/fuzzy mathematics and correspondence analysis J Hassall

WP012/99 Systemic effector conceptual model in groupware implementation J Hassall

15

-

Managing knowledge workers

WP013/99 Measuring groupware effectiveness using ordinal questionnaire data with A1/fuzzy mathematics and correspondence analysis treatments

J Hassall

WP014/99 The development of a system of social services in the Russian Federation K Gilbert

1998 WP001/98 Western intervention in accounting education in Russia: an investigation G Richer & R Pinkney

WP002/98 Managing strategy, performance and information L Worrall

WP003/98 Assessing the performance of SMEs: rules of thumb used by professional business advisors K Mole & J Hassall

WP004/98 Economac case study: Baxter healthcare, Irish manufacturing operations M Bennett & P James

WP005/98 Economac case study: Xerox Ltd M Bennett & P James

WP006/98 Economac case study: Zeneca M Bennett & P James

WP007/98 Tools for evaluating the whole life environmental performance of products M Bennett, A Hughes & P James

WP008/98 Demographic influences on purchase decision-making within UK households C Cooper

WP009/98 From mentoring to partnership: joint efforts in building a Russian management training infrastructure E Gorlenko

WP010/98 The purpose of management development: establishing a basis to compare different approaches T Bate

WP011/98 Evaluating information systems using fuzzy measures J Hassall

WP012/98 Measuring the effectiveness of information technology management: a comparative study of six UK local authorities L Worrall, D Remenyi & A Money

WP013/98 The effect on international competitiveness of differing labour standards in the textile industry of the NIS and the EU K Walsh & V Leonard

WP014/98 The effect on international competitiveness of differing labour standards in the steel industries of the NIS and the EU K Walsh & V Leonard

WP015/98 The Effect on International Competitiveness of Differing Labour Standards in the Fertiliser Industries of the NIS and the EU

K Walsh & V Leonard

WP016/98 Causal maps of information technology and information systems G Singh

WP017/98 The perceptions of public and private sector managers: a comparison L Worrall & C L Cooper

WP018/98 Information systems to support choice: a philosophical and phenomenological exploration J Hassall

WP019/98 Managers' perceptions of their organisation: an application of correspondence analysis L Worrall & C L Cooper

WP020/98 Developing journal writing skills in undergraduates: the need for journal workshops C Hockings

WP023/98 The Russian open game K Gilbert

WP024/98 A review of the black country and labour market from the Pricewaterhousecoopers West Midlands Business Survey 94-98

L Worrall

1997 WP001/97 Developing a psychometric personality instrument for sales staff selection P Jones

WP002/97 The process of management: the case of the football manager B Perry & G Davies

WP003/97 In bed with management: Trade Union involvement in an age of HRM J Black & D McCabe

WP004/97 Select classified bibliography of texts and resources relevant to management development in Russia and the former Soviet Union

N Holden & K Gilbert

WP005/97 Using heuristics to make judgements about the performance of small and medium sized businesses (SMEs)? Can we develop an improved tool to diagnose the likelihood of SME success?

K Mole

WP006/97 Making environmental management count: Baxter International's environmental financial statement M Bennett & P James

WP007/97 Quality in higher education: the problem and a solution B Kemp & V Sullivan

WP008/97 The political economy of global environmental issues and the world bank D Law

WP009/97 Some thoughts on the priority-budget alignment process in local government L Worrall & T Bill

WP010/97 The writings of Peter F Drucker: a review and personal appreciation P Starbuck

WP011/97 The impact of visionary leadership and strategic research-led OD interventions on management culture in a public sector organisation

B Hamlin, M Reidy & J Stewart

WP012/97 Learning from business studies students: issues raised by a survey of attitudes and perceptions related to independence in learning

G Lyons

WP013/97 A review of the Black Country economy and labour market from the Price Waterhouse West Midlands Business Surveys: 1994-1997

L Worrall

WP014/97 Director of football: cosmetic labelling or a sea-change? The football managers formal job role B Perry & G Davies

WP015/97 Training Russian management trainers: the role of a Western aid project E Gorlenko & K Gilbert

WP016/97 The demise of collectivism: implications for social partnership J Black, A-M Green & P Ackers

WP017/97 Geographical information systems and public policy: a review L Worrall & D Bond

WP019/97 Towards a theory of curriculum choice for undergraduate accounting courses in Britain G Richer

WP020/97 Export performance and the use of customer's language G Murcia-Bedoya & C Wright

WP021/97 How can management accounting serve sustainability? New findings and insights from a bench-marking study M Bennett & P James

WP022/97 An investigation of information systems methodologies, tools and techniques G Singh & I Allison

WP023/97 Developing a fuzzy approach to the measurement of organisational effectiveness: a local government perspective J Hassall & L Worrall

WP024/97 Making use of motivational distortion in a personality questionnaire for sales staff selection P Jones & S Poppleton

1996 WP001/96 Size isn't everything: some lessons about union size and structure from the National Union of Lock and Metal Workers J Black, A-M Greene & P Ackers

16

-

Managing knowledge workers

WP002/96 Development of performance models for co-operative information systems in an organisational context J Hassall

WP003/96 The Strategic process in local government: review and extended bibliography L Worrall, C Collinge & T Bill

WP004/96 A commentary on regional labour market skills and training issues from the Price Waterhouse West Midlands Business Survey

L Worrall

WP005/96 Aspirations and expectations in a Russian business school: the case of a joint UK/Russian management diploma K Gilbert

WP006/96 Defining a methodological framework: a commentary on the process C Goulding

17

Number WP005/03ISSN Number1363-6839Copyright

AbstractThe authorsCatherine L WangProfessor Pervaiz K Ahmed

IntroductionKnowledge workersMotivating knowledge workersTheories of choicesMain theories

Managing knowledge workers in the strategic contextPersonalisation strategyRecruitment & selectionTraining & developmentReward system

ConclusionsReferencesWorking Papers Series - previously published1999199819971996