WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

-

Upload

belen-fernandez-suarez -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

1/48

Working Paperswww.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers

MMG Working Paper 12-05 ISSN 2192-2357

Ralph GRillo / pRakash shah

Reasons to Ban? The Anti-BurqaMovement in Western Europe

MaxPlanckInstitute

fortheStudy

of

Religio

usandEthnic

Diversity

Max-P

lan

ck-InstitutzurErforschungmultireligi

ser

undmultiethnischerGesellschaften

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

2/48

Ralph Grillo and Prakash Shah

Reasons to Ban? The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe

MMG Working Paper 12-05

Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung multireligiser und multiethnischer Gesellschaften,

Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity

Gttingen

2012 by the author

ISSN 2192-2357 (MMG Working Papers Print)

Working Papers are the work of staff members as well as visitors to the Institutes events. The

analyses and opinions presented in the papers do not reect those of the Institute but are those

of the author alone.

Download: www.mmg.mpg.de/workingpapers

MPI zur Erforschung multireligiser und multiethnischer GesellschaftenMPI for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Gttingen

Hermann-Fge-Weg 11, 37073 Gttingen, Germany

Tel.: +49 (551) 4956 - 0

Fax: +49 (551) 4956 - 170

www.mmg.mpg.de

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

3/48

Abstract

During the 2000s, the dress o Muslim women in Muslim-minority countries

in Europe and elsewhere became increasingly a matter or debate and, in several

instances, the subject o legislation. In France, a ban on the wearing o the headscar

in places o education (2004) was ollowed in 2010 by the law criminalizing the wear-

ing o the ace-veil (usually but inaccurately reerred to as the burqa) in public space.

Other countries have enacted similar legislation. Muslim womens dress has histori-

cally been a controversial matter in Muslim-majority countries, too, most recently

in North Arica ollowing the Arab Spring, but the present paper concentrates on

the movement against ace-veiling in Western Europe, documenting what has been

happening and analysing the arguments proposed to justiy criminalizing this typeo garment. In doing so, the paper explores the implications or our understanding

o contemporary (ethnically and religiously) diverse societies and their governance.

Is anti-veiling legislation a protest against what is interpreted as an Islamic practice

unacceptable in liberal democracies, a sign o a wider discomort with non-European

otherness, or an expression o an underlying racism articulated in cultural terms?

Whatever the reason, is criminalization an appropriate response? An Appendix notes

some topics or urther research.

Author

Ralph GRillois Emeritus Proessor o Social Anthropology at the University o

Sussex. Email: [email protected];

Website: hp://www.sussex.ac.uk/anthropology/people/peoplelists/person/1090.

Publications include: Pluralism and the Politics o Dierence: State, Culture, and

Ethnicity in Comparative Perspective, Clarendon Press (1998); editor o The Family

in Question: Immigrant and Ethnic Minorities in Multicultural Europe, AmsterdamUniversity Press (2008); co-editor oLegal Practice and Cultural Diversity, Ashgate

(2009). Ralph Grillo is a member o the Advisory Group o the Department o

Socio-Cultural Diversity o the Max Planck Institute or the Study o Religious and

Ethnic Diversity at Gttingen.

pRakash shahis a Senior Lecturer at the School o Law, Queen Mary, Universityo London. Email: [email protected];

Website: hp://www.law.qmul.ac.uk/sta/shah.html .

mailto:[email protected]://www.sussex.ac.uk/anthropology/people/peoplelists/person/1090mailto:[email protected]://www.law.qmul.ac.uk/staff/shah.htmlhttp://www.law.qmul.ac.uk/staff/shah.htmlmailto:[email protected]://www.sussex.ac.uk/anthropology/people/peoplelists/person/1090mailto:[email protected] -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

4/48

Areas o research include ethnic minorities and diasporas in law, religion and law,

immigration, reugee and nationality law, comparative law, and legal pluralism. Edi-

tor o Ashgate book series on Cultural Diversity and Law; publications include:

Legal Practice and Cultural Diversity (Ashgate, 2009, joint editor), Law and Ethnic

Plurality: Socio-Legal Perspectives (Martinus Nijho, 2007, editor), Migration, Dias-

poras and Legal Systems in Europe (RoutledgeCavendish, 2006, co-editor), The Chal-

lenge o Asylum to Legal Systems (Cavendish, 2005, editor), and Legal Pluralism in

Conict: Coping with Cultural Diversity in Law (Glass House, 2005).

Keywords

Islam, Muslims, Europe, Face-Veiling, Burqa, Women

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

5/48

Contents

1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 7

2. Contextualizing the Debate ....................................................................... 9

3. Anti-Face-Veiling: The Rise o a Movement ............................................. 12

4. Justiying the Ban? The Arguments against Face-Veiling .......................... 16

(a) Lacit, the Secular and the Religious ............................................... 17

(b) Religion or Culture? ......................................................................... 19

(c) Not Our Culture ............................................................................. 21

(d) Transparency, Communication and Integration................................ 23

(e) Subjugation and Agency .................................................................. 27

() Identication and Security ............................................................... 28

5. Cross-Cutting Themes and Emergent Issues ............................................. 30

6. Concluding Remarks ................................................................................. 36

Appendix A: Note on Further Research ............................................................ 40

Appendix B: Brie Timeline o Events Relating to the Criminalization o

Face-Veiling in Europe .................................................................. 42

Reerences .......................................................................................................... 44

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

6/48

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

7/48

1. Introduction1

This paper discusses a number o issues arising rom the moves, in several western

European countries, to legislate against and, in particular, to criminalize the wearing

in public o what is generally called the burqa (ace-veiling). It addresses three sets

o questions, providing a general overview over what has become a growing eld

o scholarly analysis and commentary: (a) What is happening in dierent western

European countries regarding the debates and legislation concerning ace-veiling?

(b) Why is it happening? (c) What are the implications or our understanding o con-

temporary (ethnically and religiously) diverse societies and their governance? Briefy,

and obliquely, we also touch on a ourth question: What should happen? Should

ace-veiling be criminalized?There are dierent types o headgear and body covering associated with people o

Muslim aith, and to avoid ambiguity (and misleading the reader) we should make

clear that in this paper we are concerned principally, i not solely, with two modes

o emale dress which veil the ace: the burqa (a ull-body garment, including head-

covering, with typically a grid or eye-holes allowing vision), and the niqab, a body

and head-encompassing dress with the ace below the eyes covered by a veil. The

word veil (voile in French) has ound its way into public discourse (and academic

literature) to reer to what is otherwise described as a headscar (French,oulard), orhijab, though properly hijab has a wider application; it may be glossed as partition

or modesty. In France, voile integralis commonly used when reerring specically to

the burqa/niqab. The burqa is extremely rare in Europe (where it is requently associ-

ated with the style o dress advocated, or enorced, in Aghanistan by the Taliban);

the niqab, a Middle-Eastern, Arabic style o dress, is more common than the burqa,

but still very unusual. However, the word burqa is oten (mis)used in public discourse

in Europe to reer to all types o acial veiling, and discussion in legislatures and

1 The paper originated as concluding remarks by the authors at a workshop on The BurqaAair Across Europe: Between Private and Public, University o Insubria, Faculty oLaw, Como, Italy, 4-5 April 2011, organized by Alessandro Ferrari under the auspices othe RELIGARE project (hp://www.religareproject.eu/ ) unded through the EuropeanCommission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreementnumber 244635, o which Prakash Shah is a member. Case studies rom the workshopwill be published in Italian in Quaderni di Diritto e Political Ecclesiastica 2012(1). An

English edition is also in preparation or Ashgate.

http://www.religareproject.eu/http://www.religareproject.eu/ -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

8/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-058

in the media seemingly makes little or no distinction between these two varieties or

styles. Our preerred term is ace-veil.2

Womens dress, including both the ace-veil and other orms o headgear have been

much debated in Muslim-majority countries, and in some cases opposition has led

to proscriptions o various kinds (Ahmed 2011). In Turkey, there is a long-standing

prohibition on womens headgear chiefy centring on the trban (i.e. not the ace-veil

but what is known elsewhere as the hijab) that reveals an Islamic belie and relates to

what is considered appropriate within public contexts such as places o employment,

schools and universities. There is no explicit legislative basis or the prohibition, but

it is seen as being against the constitutional values o the Republic (arkolu 2010,

Yildirim 2012). Meanwhile, wearing such garments in supposedly private contexts

such as non-state employment is also not protected legally. In Egypt, a controversyconcerning the ace-veil erupted in 2009 when the late Sheikh Mohammed Tantawi, a

leading imam, reportedly said on a visit to a Cairo school that, The niqab is a tradi-

tion, it has no connection with religion (in Blomeld 2009). The imam issued aatwa

against its use in schools, and there was a campaign led by the Ministry o Education

banning the niqab rom public universities. Subsequent events (the Arab Spring) in

North Arican countries such as Tunisia have re-opened arguments or and against

ace-veiling, in the context o re-examination o the signicance o the Muslim herit-

age. These developments demonstrate that there is ar rom being a unied voice inMuslim-majority countries on matters o dress and appearance. Here, however, we

concentrate on arguments marshalled against ace-veiling, and or its criminalization,

within Western Europe.

The paper is divided into six sections. Following this introduction, the second

explores the context o the ace-veiling debate in European countries with Muslim

minorities. The third goes more deeply into the rise o the anti-ace-veiling move-

ment. The ourth summarises and explores the arguments that have been deployed

against ace-veiling and in avour o anti-ace-veiling legislation. The th urtherrefects on issues arising rom the veiling debate, and considers inter alia whether

the legislation (actual or proposed) is specically against an icon o unacceptable

Islamic practice (or indeed o Islam), or whether it is part o a wider discomort with

2 For a ull discussion, see inter alia, Bowen 2007, Dwyer 1999, Elver 2012, Fadil 2011,Fernando 2010, Hill 2011, Joppke 2009, Kili, Saharso and Sauer 2008, Killian 2007,McGoldrick 2006, Moors 2009, 2011, Parvez 2011, Schwartzbaum 2011, Shadid and VanKoningsveld 2005, Werbner 2007. To reiterate, this paper, like the Como workshop, con-cerns the ace-veil, but as we will show there is overlap between the arguments against the

burqa/niqab and those deployed previously against the hijab.

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

9/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 9

non-European otherness, or alternatively, and simply, an expression o an underlying

racism expressed in cultural terms. It also asks whether, whatever ones views about

veiling, criminalization is an appropriate response. The concluding remarks contrast

alternative ways in which more general lessons might be drawn rom these events,

rst, through the lens o two kinds o liberalism (multicultural and muscular), and

secondly through a perspective which problematizes the liberal agenda itsel. A short

Appendix notes some topics on which urther research is desirable.

2. Contextualising the Debate

In the course o the rst decade o the 21st century, says Moors (2009: 406), ace-

veiling has turned rom a nonissue into a hyperbolic threat to the nation-state. The

number o adult women who wear the burqa or niqab in Western countries with

Muslim minorities is very small; typically well below hal o one per cent o the Mus-

lim population, though anecdotal evidence suggests that its use has been increasing

(Meer, Dwyer and Modood 2010). The current rush to legislation, however, needs

to be set in the context o what has been called the backlash against multicultura-

lism (inter alia Vertovec and Wessendor eds. 2010), that has been developing across

Europe through the 1990s and into the 2000s, and which was accentuated by inter-

ventions by leading politicians such as Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, and David

Cameron in 2010-11 (Modood 2011). In brie, there has been rising tension in Europe

and North America (and in Australia and New Zealand) around the governance o

diversity with, in many countries, a rejection o policies which previously took a rela-

tively benign stance on cultural and religious dierence. Indeed, in some cases, such

as ace-veiling, or mosques and minarets, there is evidence or a growing tendency to

call or the criminalization o ethnic alterity (Ballard 2011), along with a reassertion

o the cultural content o citizenship, its culturalization (Moors 2009). None o this

is to deny that in many European countries over the last thirty years much has been

done to accommodate alterity in general and Muslim concerns in particular (Menski

2008, Shadid and Van Koningsveld 2002), and this process continues alongside an

increasingly strident opposition to other cultural and religious practices. The present

paper, however, is concerned with an important and now widespread instance o

opposition to accommodation, o lines being drawn on a seemingly systematic basis,

with variations, across various jurisdictions.

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

10/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0510

These concerns about national identities and values seemingly refect a deepening

cultural anxiety (Grillo 2003), which in broad terms may be understood against the

background o economic and political change and uncertainty, especially in a post-

9/11 world. Conjunctural processes such as transnationalism and neoliberal globali-

zation (and more recently its near breakdown) have delivered an epoch o disembed-

ding (Giddens 1991), threatening ways o lie and livelihood, and the order o things,

and posing dicult questions about identity. Anxiety is unsurprising, and in many

places it has been articulated by political parties or movements which are strongly

nationalist or regionalist and typically anti-state, anti-big government, and anti-

Europe. They are also, typically, anti-immigrant and anti-reugee. Although opposi-

tion to immigrants refects many concerns, including the belie that migrants take an

unair share o scarce resources, it is oten voiced through a discourse that contraststhe (imagined) immigrant with the (equally imagined) indigenous national subject.

Sometimes this is couched in terms o a generalized Western or European (per-

haps Judeo-Christian) subject and his/her values, which are in danger o being over-

whelmed by the incoming tide o immigrants and asylum-seekers. Oten, however, as

with movements o the political right and governments which co-opt their rhetoric,

it is specically the imagined national (native) citizen (British/French/Danish etc)

who is threatened. Such movements inevitably simpliy the issues. Roy (2010) has

observed that while new church movements, which are fourishing among the moremarginalized sections o various societies, also include immigrants, they may also be

at the oreront o campaigns against multiculturalism seen as making unair conces-

sions to members o other, minority religious groups.

Islam is an integral part o this. The eighteen million or so (Pew Forum 2011:

27) Muslims o migrant or reugee origin in Western Europe have an implantation

which now stretches into the second and third generations. Their presence is pre-

dominantly a amily one (Nielsen 2004), with implications or housing, health and

educational systems in countries that in varying degrees are implementing neoliberaleconomic and social agendas, running down state welare provision. Though many

are long-term migrants and/or have been born and brought up in the countries o

immigration, relationships with societies o origin have not necessarily diminished.

On the contrary, the signicance o transnationalism, and what is understood as the

transnational character o Islam and o migrant populations who espouse it, is now

ully apparent (Bowen 2009, Hellum et al 2011). At the same time, as Gerholm (1994:

206) reminded us, an authentic Muslim lie demands an extensive inrastructure:

mosques with minarets, schools, halalbutchers, cemeteries, and this has been widely

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

11/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 11

achieved, oten, as Gerholm also said, not without resistance. Along with the chang-

ing nature o the Islamic presence with its established (and sometimes highly visible)

inrastructure, and increasing demands or wider recognition, there is serious ques-

tioning (on all sides) about whether it is possible to be a Muslim in a Western country

and, i so, what kind o a Muslim it is possible to be (Bowen 2009, Ramadan 1999,

2004, 2009).

Islam in Europe is very diverse in terms o the origins o the Muslim popula-

tion, the varieties o the aith they ollow, and indeed their religiosity, but concern

about the ailure o Muslims (in general) to integrate is at the heart o the current

backlash against multiculturalism (Bowen 2011). There is alarm about ghettoization,

communal separatism and (sel)exclusion, accompanied by demands that incomers

learn the national language and declare their loyalty to the nation-state where theyreside, rather than to that whence they came, or to an international umma. Politi-

cians stress the need to reassert core values against those thought at odds with them.

9/11 and subsequent events are obviously part o this, with demands or integra-

tion oten couched in terms o security and concerns about terrorism. The global

Islamic revival and the rising attraction o Salast and similar Islamic ideologies

in the Islamic world (and among people o Muslim aith in Europe) maniestly also

have a part to play. Islamophobia, which o course has a long prior history, is voiced

through the trope o the spectre o undamentalism, and, in contemporary rhetoric,what can only be described as paranoid antasies about the threatened Islamization

o Europe, which statements by some outspoken Muslim clerics in eect encourage.

There are, too, the successive oil crises, and concerns about energy resources and

prices, and not least conficts in the Middle East pre and post-9/11, all o which have

conspired to construct Muslim as a demonized social and cultural category.

Besides this, and to an extent provoked by it, is the heightening o the historical

debate about religion and secularism and the relationship between them, most obvi-

ously in France, concerning the meaning and implication o lacit. Elsewhere, too,there has been much discussion (and dispute) about the role o religious symbols and

modes o identication in public space and the public sphere. In this context, the

Lautsicase, in which a non-Christian who objected to the compulsory display o the

crucix in Italian schools took the government to the Strasbourg Court (European

Court o Human Rights 2011), is one key instance in an ongoing dialectic. However,

religion in such discussions oten means Islam, while Christianity, its symbolism,

and its place within European society, has infuential deenders (Ratzinger and Pera

2006).

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

12/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0512

3. Anti-Face-Veiling: The Rise o a Movement

The European movement against ace-veiling is now widespread with calls to imple-

ment a ban debated or implemented (nationally or locally) in France, Belgium, Italy,

Spain, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and Germany. (A brie time-line o events

relating to the criminalization o ace-veiling in Europe may be ound in Appen-

dix B.) The way it has moved rom country to country makes it seem like a orm o

political Swine Flu, or like The Plague in Camuss allegorical novel, although the

spread o policy across jurisdictions, which the ace-veil ban illustrates, is not nec-

essarily unique. As Joppke (2007) suggests, what he calls repressive liberalism has

been widely taken up across Europe and beyond. However, in this section we ask

how, and in what ways, has the issue o the ace-veil become so rapidly politicizedand taken up by political parties and their leaders, national and local? What are the

orces (social, political, cultural and religious) behind the move towards legislation

in the various countries and contexts? Why is the ban so widely welcomed by local

populations?

The origins o the European move to ban ace-veiling may be traced ultimately to

France in 1989 when a local head teacher in the town o Creil sought to exclude three

young girls rom attending school wearing headscarves (hijabs, and not the ace-veil).

The consequences o that event, and other local initiatives during the same period,are too well-known to recapitulate (Bowen 2007, McGoldrick 2006, Scott 2007 etc),

but the arguments o that period (leading to legislation to enorce an educational ban

in 2004) resurace in various guises in the current debate about ace-veiling (below).

The amous Le Monde cartoon that appeared at the time, o a young woman in a

headscar with a grotesque and threatening male gure behind her (Are you or or

against the veil at school? Le Monde, 7 November 1989, see among others Bloul

1996), sent a message o enduring signicance; there are many more recent examples

o this genre (World Press Cartoon 2011). Also in 1989 the Rushdie Aair, the atwapronounced in Iran against the author or his book Satanic Verses led to distur-

bances (and book burnings) in many places including Britain, opening up concerns

about the implications o (militant) Islam or Western countries embracing liberal

principles including reedom o speech: religion was seemingly re-entering a space

whence it had been ejected.

The Gerin Commission (2010), tasked by the French Government to examine the

question o the ace-veil, undertook a census o Le Monde articles discussing the

niqab or burqa between 1993-2009. Most concerned Aghanistan with almost noth-

-

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

13/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 13

ing on Western countries beore 2003. From c. 2007-8, however, the volume o arti-

cles dealing with Western Europe overtook those concerned with Muslim-majority

countries, as ace-veiling became increasingly a matter o public debate and media

attention; Moors (2009) notes a similar pattern in the Dutch press. In the early-

mid 2000s, in act, there had already been a number o local initiatives against veil-

ing, notably in Belgium, and in autumn 2005, a specic proposal or a ban was put

orward by the Dutch Immigration Minister, Rita Verdonk, o the Peoples Party

or Freedom and Democracy, at the instigation o another politician, Geert Wilders.

Verdonk argued that ace-covering was inter alia a symbol o division (between the

West and Islam) and was not in harmony with the integration o Muslims and the

emancipation o women.3 The Dutch government established a commission to con-

sider a ban, which was supported by many parliamentarians. A urther developmentduring this period was the intervention in October 2006 by the British politician Jack

Straw (then a leading member o the Labour government), who in his weekly column

in a local newspaper said that he had reservations about interviewing constituents

wearing a veil (Above all, it was because I elt uncomortable about talking to some-

one ace-to-ace who I could not see4). This comment led to considerable discussion

in the media (Werbner 2007, Hill 2011). A little later, the 2008 decision o the French

Conseil dtat to reuse naturalization to a woman who wore the veil (the case o

Madame M, see urther below) also attracted much attention.Five things about these developments may be noted. First, in many instances local

initiatives have been infuential, attracting national (and international) media atten-

tion, and sparking the interest o national politicians, and indeed politicians in other

countries. This was certainly the case in France in the earlier headscar aair. Like-

wise, the Swiss movement against minarets stemmed rom a reusal by the authorities

in a small town (Wangen bei Olten) to authorize the construction o a building by a

Turkish association. That initiative was subsequently taken up by the Swiss Peoples

Party and led to a national reerendum in 2009 in which such bans received the sup-port o 58 per cent o those voting. In the case o ace-veiling, local initiatives, by

mayors and town councils are widely reported or Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands

and Spain. In the UK, too, where there is no ormal (national) ban on either head-

scarves or ace-veilings, cases concerning Islamic dress that have come beore the

3 hp://forums.skadi.net/showthread.php?t=80189 [accessed: 31 October 2011].4 hp://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+ per cent28black-

burn per cent29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_o_your_veils/

[accessed: 31 October 2011].

http://forums.skadi.net/showthread.php?t=80189http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+%28blackburn%29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_off_your_veils/http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+%28blackburn%29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_off_your_veils/http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+%28blackburn%29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_off_your_veils/http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+%28blackburn%29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_off_your_veils/http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/archive/2006/10/05/Blackburn+%28blackburn%29/954145.Straw_in_plea_to_Muslim_women__Take_off_your_veils/http://forums.skadi.net/showthread.php?t=80189 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

14/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0514

courts have been the result o actions by local teachers or boards o school governors

who have considerable autonomy in such matters.5 Thus much that happens seems

bottom-up rather than top-down: Jack Straws comments were originally in a local

newspaper read by his constituents.

Secondly, although parties and movements o the centre (and extreme) right are

highly active, nationally and locally, in the debate and in bans when they are pro-

posed and enacted, by no means is the movement solely composed o groups that are

typically xenophobic. Opposition to ace-veiling, and indeed Islam at large, encom-

passes a wide range o opinion, and in the case o ace-veiling this includes many

eminist groups and also groups (such as the French Communist Party) on the politi-

cal let (Dumouchel 2010). Such conederations o opinion rom across the political

spectrum may be observed in Belgium, where ace-veiling seems to have been theonly issue that was able to unite the countrys ractious legislature, in Spain, and in

Switzerland at the time o the reerendum on minarets.The sort o diusion thatthe ace-veil policies illustrate, may represent a particular instance o what Kriesi et

al (2008) have described as a longer-term shit to a orm o politics that emphasises

cultural issues such as mass immigration and resistance to European integration, and

in which the traditional ocus o the political debate on economic issues has been

downplayed or reinterpreted in terms o such cultural cleavages. Whether this con-

tinues to be the case in the current climate o economic instability remains to be seen.Thirdly, the movement oten has strong popular support. In Britain, which has

declined to implement a ban (Immigration Minister, Damian Green, in July 2010,

described such a response as un-British6),opinion polls nevertheless suggest thatthe majority o respondents would support one. A poll in November 2006, ollowing

Straws speech, ound 53 per cent in avour o a ban, 40 per cent against. A later poll

(Harris Interactive 2010) reported 57 per cent in avour, 26 per cent against. That poll

also sampled opinion in various other countries recording the percentage in avour

as ollows:

5 R (on the application o Begum) v Headteacher and Governors o Denbigh High School[2006] UKHL 15; R (on the application o X) v The Headteacher o Y School [2007]EWHC 298, [2007] All ER (D) 267 (both student cases); Azmi v Kirklees MetropolitanBorough Council[2007] I.C.R. 1154 (case o a teacher wearing a ace-veil). See also Malik2011, Hill 2011.

6 hp://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-10674973 [accessed 1 August 2011]

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-10674973http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-10674973 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

15/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 15

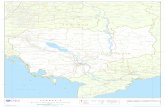

Table 1. Percentage Reported to Favour Face-Veil Ban in Various Countries

France 70

Spain 65

Italy 63

UK 57

Germany 50

USA 33

Source: Harris Interactive 2010

The reliability o such polls may be disputed, given that they pose an abstract ques-

tion rather than asking individuals to respond to an issue that concerns them, or

someone they know, personally. Nonetheless, they provide a rough gauge o public

sentiment.

Fourthly, although oten locally case specic in origin, moves to ban ace-veiling

have requently been taken up with alacrity by national politicians (or example in

Belgium; in Spain, too, though perhaps less enthusiastically), and closely ollowed by

local and national opinion-makers in other countries. There seems to have been an

outbreak o international me-tooism, to the extent that conspiracy theorists might

postulate a concerted international campaign. Those opposed to ace-veiling (or whoseek to deend it), have drawn on debates and events in other countries, and there

exists, in this sphere as in others, a sort o transnational intertextuality, or example

in the way that developments in France concerning both the headscar and ace-

veiling infuenced what was happening in Belgium (Fadil 2011), or the views o the

French philosopher and eminist, Elizabeth Badinter, expressed to the Gerin Com-

mission7, were taken up elsewhere. Certainly the arguments o British advocates o

a ban, and the governments response, took note o what was happening in Europe.

There is a cross-national interweaving o political, academic and popular discourse,embracing a skein o vocabulary, sources, tropes, ideas, instances, paradigms, and

public debates on ace-veiling that cannot be ully comprehended without taking

into account this wider context in which they are embedded and rom which they

emerge.

7 Commission Gerin, Audition de Mme lisabeth Badinter, philosophe. Sance du mercredi9 septembre 2009, hp://www.assemblee-naonale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.

asp [accessed 1 November 2011].

http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asp -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

16/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0516

Finally, there is the specic infuence o politicians addressing international audi-

ences, notably the Dutch politician Geert Wilders (Moors 2009, 2011). Wilders has

visited and spoken in numerous countries (including the UK, rom which he had

originally been banned), against the alleged Islamization o Europe and in avour o

restrictions on the practice o the Muslim aith, including banning ace-veiling. The

European Parliament also became a orum or exchange o views among European

politicians opposed to the burqa. In May 2010, in an editorial in the German daily

Bild, Silvana Koch-Mehrin, the head o the Free Democrats in the European Parlia-

ment and a member o that Parliaments highest administrative body, the bureau,

condemned public ace-veiling as an enormous attack on the rights o women and

a mobile prison, and advocated a Europe-wide ban.8

4. Justiying the Ban? The Arguments against Face-Veiling

Shortly ater the French ace-veiling ban came into orce (in April 2011), the British

journalist, Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, ounder o British Muslims or Secular Demo-

cracy, signalled her opposition to the veil in an article in the Independent entitled

Sixteen reasons why I object to this dangerous cover-up (2011).9 Here we summarize,

with brie comments, our own analysis o the arguments requently encountered inpublic debate.

Pro and anti-veiling discourse consists o variations on several thematic antino-

mies:

The secular vs. the religious: what should be the role o public religious expression

in a secular society?

Religion vs. culture: Is veiling a religious obligation (and as such an expression o

radical Islam)? Is it a voluntarily adopted cultural preerence? I religious, does

this imply special rights? I cultural, is any protection available?

8 hp://euobserver.com/22/29991 A video o a meeting on Burqa and Womens Rights(10 June 2010), organized by the Alliance o Liberals and Democrats or Europe is avail-able at hp://oldsite.alde.eu/en/details/?no_cache=1&tx_news per cent5B_news percent5D=23101&cHash=3212cc7cd8 [accessed 20 October 2011].

9 There is extensive discussion in, among others, Dumouchel 2010, Joppke 2011, Lenard2010, Moors 2009, Mullally 2011, Parvez 2011, Saharso and Lettinga 2008, Shadid andVan Koningsveld 2005, Silvestri 2009, 2010, and most persuasively Howard 2009. Alib-hai-Browns article actually appeared during the workshop at Como in April 2011, as theauthors were assembling their own list o the arguments made by the dierent European

legislatures.

http://euobserver.com/22/29991http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_92ois4pchwhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_92ois4pchwhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_92ois4pchwhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_92ois4pchwhttp://euobserver.com/22/29991 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

17/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 17

Our culture vs. your culture: Whether cultural or religious, does veiling repre-

sent an unacceptable otherness?

Integration vs. parallel lives: does veiling oster communitarianism and under-

mine an open society?

Womens subordination vs. womens agency: Does veiling signiy patriarchy and

the submission o women? What i women (apparently) choose to veil?

Cultural (or religious) rights vs. womens rights: can/should rights be hierarchized?

These themes cross-cut, intersect, and contradict one another in complex ways, as the

ollowing discussion shows.

(a) Lacit, the Secular and the Religious

Lacit, as a principle o French republican governance, is not the same as secularism

or anti-clericalism, or hostility towards religion as such, though anti-religious senti-

ment has clearly motivated some opponents o ace-veiling. Lacits deence was, o

course, an important ocial argument o French opponents o the hijab, and was

employed specically against wearing the headscar in state schools. In 2003, ollow-

ing initiatives by then Minister o the Interior Nicolas Sarkozy, a commission was

established (Commission Stasi 2003) to refect on the application o the principle olacit in the Republic. Its report rehearsed the history o the idea in French thought

rom the Revolution, tracing its articulation through legislation in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries. Concerned with the way that demands or the recognition o

dierence had become increasingly vocal in schools, hospitals, the legal system and

the workplace, the Commission concluded that while diversity should be respected,

the principle o lacit in the public sphere should be re-armed. In particular, it

expressed alarm about articles (such as clothing) o an ostentatious or provocative

nature that might be taken as signs o identity, and recommended legislation to orbid

the wearing o them in public education. Ater much debate, the French parliament

inserted a clause in the Education Code: Pupils in public schools are prohibited rom

the carrying o symbols or wearing o clothing which are ostentatiously religious. 10

10 LOI n 2004-228 du 15 mars 2004. The recent debate on the ace-veil has echoed thisopposition to the ostentatious display o religious aliation. As one internet commen-tator put it: La rue, les espaces publics ou privs, ne doivent pas tolrer un afchage ves-timentaire qui ne ont que mettre en vidence les dirences de culture, hp://www.lex-press.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143 [accessed 11 January 2012],

our emphasis.

http://www.lexpress.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143http://www.lexpress.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143http://www.lexpress.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143http://www.lexpress.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143http://www.lexpress.fr/emploi-carriere/emploi/commentaire.asp?id=945143 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

18/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0518

This amendment (which aected other religious groups besides Muslims) was

widely accepted, though opposed by many Muslims in France and elsewhere in

Europe. Commenting on these events, Bowen (2004: 34) observed that

the norm o public lacit directs citizens to leave behind their ethnic and religious iden-tities and all visible emblems o those identities and to assume the shared identity andvalues associated with the Republic whenever they inhabit public space. Scholars andocials justiy this norm by arguing that to proclaim publicly and loudly ones privateidentities is to generate division and confict in a society.

This orm olacit demands a public citizenship characterized by a-cultural, and spe-

cically a-religious individualism; the citizen stripped o all public religious appur-

tenance. As Mullally comments (2011: 32), cultural dierence is to be pushed to therealms o the private; the public sphere is to remain culture ree, neutral, universal. It

is an ideology, which, or example, led one French Interior Minister, Claude Guant,

to declare that users o public services (such as hospitals) should not display any-

thing that suggested a religious preerence. Consonant with that, he also maintained

that it was inadmissible or a woman to reuse medical treatment rom a man.11

Lacit was not, however, the sole or perhaps even the most signicant principle at

stake in the move to ban ace-veiling in France or indeed elsewhere. In act, as Jop-

pke (2011: 10) argues, lacit move[d] into the background. He oers two reasons or

this: rst, because the proposed ban would extend to all public spaces (and not just

state schools etc.), and second because in the course o the debate it was concluded

that ace-veiling was not a religious prescription. The Commission Gerin drew a

distinction between the hijab (conspicuously religious) and ace-veiling, arguing that

because the ace-veil was not laid down by Islam (the Commission had taken evi-

dence on this point), lacit, while not irrelevant, was not the heart o the problem.

Joppke (2011: 11) discusses this point in some detail, arguing that: lacit is a prin-

ciple to regulate religion, and that i the burqa is seen as extrinsic to Islam, and not

as religious expression at all, it alls outside the ambit o lacit. While technicallycorrect, it did not prevent politicians, including the President, rom continuing to

express opposition to ace-veiling in the name o lacit.

11 Reported in Libration, 24 March 2011, hp://www.liberaon.fr/poliques/01012327512-les-usagers-de-certains-services-publics-ne-doivent-pas-porter-de-signes-religieux

[accessed: 31 October 2011].

http://www.liberation.fr/politiques/01012327512-les-usagers-de-certains-services-publics-ne-doivent-pas-porter-de-signes-religieuxhttp://www.liberation.fr/politiques/01012327512-les-usagers-de-certains-services-publics-ne-doivent-pas-porter-de-signes-religieuxhttp://www.liberation.fr/politiques/01012327512-les-usagers-de-certains-services-publics-ne-doivent-pas-porter-de-signes-religieuxhttp://www.liberation.fr/politiques/01012327512-les-usagers-de-certains-services-publics-ne-doivent-pas-porter-de-signes-religieux -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

19/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 19

(b) Religion or Culture?

There has long been debate about modesty and veiling in Muslim-majority countries,

about what the religious sources say, and how they have been interpreted in dier-ent contexts and at dierent times. Many Muslims would in act agree that covering,

o the kind represented by ace-veiling, is by no means a requirement o the aith,

though emale and male modesty is (Sardar 2011). This is the position oten taken

by Muslims in Western countries too.12 In his evidence to the Gerin Commission the

philosopher Tariq Ramadan stated:

La trs grande majorit des savants et courants sunnites et chiites estiment quela burqa ou le niqab ne sont pas une prescription islamique. Le consensus parmi

les savants est que le oulard en est une mais pas le niqab et la burqa. Mais vousavez une interprtation qui existe, qui est minoritaire, et dont vous ne pourrez pasdisqualier la prsence mme si vous tes en opposition avec le prsuppos et laconclusion, ce qui est mon cas. Pour ce qui me concerne, je ne cesse dexpliqueraux diverses communauts musulmanes que linterprtation qui conclut au portdu niqab ou de la burqa est rductrice, quelle trahit le sens et lesprit mme de larrence musulmane. Cest un travail que je ais de lintrieur et que nous devonsmener. Mais il aut reconnatre le ait clair et objecti quune tradition maintientque telle est la comprhension de lislam. Cette tradition se rclame de la pratiquedes pouses du Prophte pour lriger en norme applicable toutes les emmes, alors

que les autres savants ont gnralement la distinction entre ce qui est spciique auxpouses du Prophte et ce qui est demand pour les autres emmes.13

12 See Shirazi and Mishra (2010) or an American Muslim perspective, also Schwartzbaum(2011).

13 English translation by Ralph Grillo: The vast majority o Sunni and Shia scholars believethat the burqa or niqab are not an Islamic requirement. The consensus is that the head-scar is obligatory, but not the ace-veil. But there is a minority interpretation which youmay not disregard even i, as I do, you reject the premises, and the conclusion which is

drawn rom them. For my own part I have unceasingly explained to the various Muslimcommunities that the interpretation insisting on the wearing o the ace-veil is simplistic,that it betrays the meaning and spirit o the Islamic text. This is a task which I undertakewithin the Islamic community and which we have a duty to undertake. But one mustrecognize the clear and objective act that there is a tradition which maintains that suchan interpretation is the true understanding o Islam. This tradition adduces the exampleo the practices o the Prophets wives to establish a standard or all women, despite theact that other scholars generally distinguish between what is specic to the Prophetswives and what is expected o other women, Commission Gerin, Audition de M. TariqRamadan. Sance du mercredi 2 dcembre 2009, hp://www.assemblee-naonale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asp [accessed 1 November 2011]. Elsewhere he commented:

the niqab or the burqa are not Islamic prescriptions. This is what I believe the mainstream

http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/09-10/c0910015.asp -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

20/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0520

Ramadans evidence sums up the reasons or the existence o a range o positions

within Islamic law and the diculty that legislators or judges may ace when evalua-

ting the obligatory nature o the veil or Muslim women. While many Muslims would

agree with the argument that veiling is not a religious requirement, and in France, or

example, supported the previous prohibition on wearing the headscar in schools

(Killian 2007), others would claim that ace-veiling is indeed prescribed by Islam, or

at any rate their interpretation o the texts.14 Emma Tarlo cites the example o male

and emale supporters o Hizb ut-Tahrir, who advocate what she calls a radical sar-

torial activism (2005: 14; see also Tarlo 2010).15 However, supporters o the ban have

contended that since there is disagreement among Muslims as to the religious obliga-

tion to veil the ace, womens decisions to do so must necessarily be interpreted as a

choice, and moreover as apoliticalrather than a religious choice (Lenard 2010: 314).Thus, despite the plurality o Muslim interpretations o the sources o their tradition,

the Gerin Commission concluded that the veil is not as such religious, and as Joppke

ironically notes (2011: 31): the limits o restricting Islam could be transgressed only

by denying that the burqa is part o Islam.

Yet, although some claim that ace-veiling is a customary rather than religious

practice (Yasmin Alibhai-Brown or example proclaims that it is pre-Islamic), and

hence not protected by legislation or conventions guaranteeing the reedom o reli-

gion or protection rom discrimination,16 others condemn it as an instance o hard-line Sharia in practice, that is, as quintessential radical Islam: it is, said Elizabeth

Badinter ltendard des salastes(the Salasts banner).17 As Tissot summarises

their argument (2011: 43): Women in niqab are the Trojan horse o extremist Islam-

ism. In this view, the cloth hides not only a ace but secret intentions as well: to

attack secularism and impose Islamic rule. It represents political Islamism o the

kind ound, it is argued, in certain Muslim-majority countries, and specically the

believes as well, even though we have tiny groups saying this, hp://pewforum.org/Poli-cs-and-Elecons/A-Conversaon-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspx [accessed 22 October 2011].

14 For Muslim internal debates on veiling and a variety o interpretations o the texts see:hp://www.ahlalhdeeth.com/vbe/showthread.php?p=84015 and hp://www.nymes.com/2011/09/21/world/europe/21iht-leer21.html?_r=1 [accessed 1 November 2011].

15 Previously, the European Council or Fatwas and Research had declared that wearing theheadscar was a devotional commandment and a duty prescribed by the Islamic Law,and not merely a religious or political symbol (in Shadid and Van Koningsveld 2005: 36).

16 See Moors 2009, 2011, and Saharso and Lettinga 2008 on how anti-discrimination lawsaect legislation that might be interpreted as anti-Muslim.

17 Commission Gerin, Audition de Mme lisabeth Badinter, philosophe. Sance du mercredi

9 septembre 2009, hp://www.assemblee-naonale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asp [accessed 1 November 2011].

http://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/A-Conversation-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspxhttp://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/A-Conversation-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspxhttp://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/A-Conversation-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspxhttp://www.ahlalhdeeth.com/vbe/showthread.php?p=84015http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/21/world/europe/21iht-letter21.html?_r=1http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/21/world/europe/21iht-letter21.html?_r=1http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/21/world/europe/21iht-letter21.html?_r=1http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/21/world/europe/21iht-letter21.html?_r=1http://www.ahlalhdeeth.com/vbe/showthread.php?p=84015http://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/A-Conversation-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspxhttp://pewforum.org/Politics-and-Elections/A-Conversation-With-Tariq-Ramadan.aspx -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

21/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 21

kind o implementation o Sharia ound in Aghanistan under the Taliban. This

is consonant with the way Western stereotypes oten stress extreme interpretations

o Islam and Muslim practice, or indeed assume certain cultural practices, such

as orced marriages, to be Islamic. An example is provided by Geert Wilders in a

speech delivered in 2011, in Rome and elsewhere, including Canada: in some neigh-

bourhoods, Islamic regulations are already being enorced also on non-Muslims.

Womens rights are being trampled. We are conronted with headscarves and burqas,

polygamy, emale genital mutilation, honor-killings (Wilders 2011).

The extent to which veiling and other orms o dress may represent radical, politi-

cal Islamism is contested. Certainly there is some evidence or this in the UK where

Dwyer (1999: 19) has argued that wearing the headscar has acted or some young

British Muslims as a symbol o political Islamism by which individuals can pro-ess their identity as Muslims in opposition to racialized discourses o exclusion, e.g.

as a deant response to street racism.18 On the other hand, Parvezs detailed study o

niqab-wearing Muslim women in Lyon contends that their Salast-infuenced Islam-

ism is in act a-political, or rather anti-political. She oers three reasons or this:

First, the women are engaged in a struggle to deend, expand, and recongure the privatesphere against the intrusions o the state. Second, they are building a moral communityto support each other through the economic and social ostracization they all ace. Third,

they emphasize their spiritual conditions and state o serenity above material lie (Parvez2011: 289).

Their Salasm represents a retreat into a moral community, an interiorization o

religion (Killian 2007: 314), comparable to the path taken by intellectuals in ormer

communist Eastern Europe. This has a bearing on the issue o integration, discussed

below.

(c) Not Our Culture.Public ace-veiling, said Euro MP Silvana Koch-Mehrin, characterizes values we

in Europe do not share.19 Similarly, in an interview with Anglia Television News

(3 February 2010), the British MP Phillip Hollobone, who in 2010 proposed a private

18 Tarlo (2005: 14) indicates that the plainti s brother in the Begum case was closely asso-ciated with the Islamist Hizb ut-Tahrir.

19 hp://euobserver.com/22/29991 [accessed 1 November 2011]

http://euobserver.com/22/29991http://euobserver.com/22/29991 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

22/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0522

members Bill, the Face Coverings (Regulation) Bill,20 to ban the burqa, described it

as:

the most ridiculous piece o dress that you can have. The idea that you would go round ina modern society with your ace covered is just simply absurd. And o course its part othe British way o lie to pass people in the street, smile at them, say a cheery hello. Andyou cant do that i people are wearing burqas.

Whether religious prescription, or cultural practice, whether voluntary or not, is or

some beside the point. Whatever its status, ace-veiling, they argue, is not part o our

culture. This may reer to the historic European, Judeo-Christian culture o West-

ern nation-states, the values and practices o particular societies (The British way o

lie), or the public culture o contemporary liberal, democratic, secular democracies,sometimes all three. The rst two beg the question o other interpretations o what

might be meant by European or national cultures. Leaving aside the apparel that

women in Europe have historically been required to wear, including veils, the argu-

ment treats the Muslim religious/cultural practice o veiling as un-European, even

i ollowed by those born and brought up in the (European) country o residence.

By this denition it is impossible or such people (immigrants and ethnic minorities

o immigrant or reugee background) to be treated as European unless and until

they adopt what is dened as European practice. The decision o the French Con-

seil dEtat in Madame Munderlines this, since it regarded ace-veiling as not only

undesirable but as a sign o non-assimilation (Bowen 2009). The woman concerned,

it ruled, had:

adopt une pratique radicale de sa religion, incompatible avec les valeurs essen-tielles de la communaut ranaise, et notamment avec le principe dgalit dessexes; quainsi, elle ne remplit pas la condition dassimilation.21

20 A private members Bill is a proposal or legislation by a Member o Parliament not amember o the government. The text o the Bill is at hp://www.publicaons.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmbills/020/11020.i-i.html. Like most such measures, it is unlikely topass into law. The Bill was scheduled or its second reading in the House o Commons on3 February 2012, but as the House did not sit on that day it was not debated ( hp://ser-vices.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulaon.html, accessed 6 March 2012),and thus delayed once more.

21 English translation: adopted a radical religious practice incompatible with the essentialvalues o the French community, and especially with the principle o sexual equality; inthat way she does not ulll the condition o assimilation, No. 286798 Conseil dEtat,

27 juin 2008.

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmbills/020/11020.i-i.htmlhttp://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmbills/020/11020.i-i.htmlhttp://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulation.htmlhttp://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulation.htmlhttp://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulation.htmlhttp://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulation.htmlhttp://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-11/facecoveringsregulation.htmlhttp://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmbills/020/11020.i-i.htmlhttp://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmbills/020/11020.i-i.html -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

23/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 23

The argument concerning ace-veilings incompatibility with contemporary civic

principles is exemplied by Spanish opposition to the burqa on the ground that it

inconsonant with the idea o modernity to which the population o cities such as

Barcelona aspire (Fernndez 2011). More generally, because veiling is believed to

contravene the political and other rights o women, it is held to be incompatible with

the liberal democratic principles that underpin governance in much o Europe.

For some, then, ace-veiling stands metonymically (almost literally) or the Islami-

cized (emale) body, and then or Islam itsel, at any rate extreme Islamism (some

would assert that Islam is always already extreme), and has thus become a symbol

standing or all o those things that are thought to be inimical to Western (Judaeo-

Christian) values, liberal democratic principles o individual reedom and gender

equality (Mancini 2011), and modernity. For others it simply represents an unaccep-table otherness, an unwelcome racial or cultural presence. In either case, it perhaps

does not matter how many or how ew are the women who actually veil (though

some would argue that those ew represent the thin end o a wedge): the ace-veil is

simply not our culture. This moti appears in other guises, too.

(d) Transparency, Communication and Integration

The Republic is lived with the ace uncovered, said French Justice Minister MichleAlliot-Marie (in Joppke 2011: 28). One Belgian parliamentarian and opponent o

ace-veiling, Daniel Bacquelaine, declared that We cannot allow someone to claim

the right to look at others without being seen (quoted in The Guardian, 31 March

2010). This echoes Elizabeth Badinters evidence to the Gerin Commission, which

makes the point very orcibly: Porter le voile intgral, cest reuser absolument den-

trer en contact avec autrui ou, plus exactement, reuser la rciprocit: la emme ainsi

vtue sarroge le droit de me voir mais me reuse le droit de la voir. 22 The view is

widely shared. Thus,utur08, in a comment on the Guardian website:every person has a right to see the ace o another person in the street, in a pub-lic building, in school, stores, banks etc. It is how everybody protects him/hersel:

22 English translation: Wearing the ace-veil represents a reusal to engage with other peo-ple, or more precisely a rejection o reciprocity: a woman wearing a veil assumes theright to look at me, but rejects my right to look at her, Commission Gerin, Audition deMme lisabeth Badinter, philosophe. Sance du mercredi 9 septembre 2009), hp://www.

assemblee-naonale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asp [accessed 1 November 2011].

http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asphttp://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/cr-miburqa/08-09/c0809004.asp -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

24/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0524

by looking at the ace o another. Nobody should have to trust that the womanunder the veil is decent without seeing her ace.23

Martha Nussbaum (2010), in an article in the New York Times, summarizes this as:transparency and reciprocity proper to relations between citizens is impeded by cov-

ering part o the ace.24

The transparency argument overlaps with an argument rom olk-sociolinguistics,

i.e. rom popular (not necessarily scientic) assumptions about the nature o com-

munication and the visual channels necessary or satisactory communication to take

place.25 This point was made in Britain in 2006 by Jack Straw. The value o a meet-

ing, said Straw, as opposed to a letter or phone call, is so that you can almost lite-

rally see what the other person means, and not just hear what they say. This wasalso put to the British Parliament by Philip Hollobone:

Heres a woman who, through her dress, is eectively saying that she does not want tohave any normal human dialogue or interaction with anyone else when a woman wearsthe burqa, she is unable to engage in normal, everyday visual interaction with everyoneelse It is deliberately designed to prevent others rom gazing on that persons ace.[This] goes against the British way o lie we can all see who [an]other person is andwe interact both verbally and through those little visual acial signals that are all part ointeracting with each other as human beings. (House o Commons Debates, 11 March

2010, cols. 483-4).

While this may represent an ethnocentric view o what constitutes the necessary con-

ditions or eective communication,26 it could nevertheless be insisted that, aside

rom casual encounters, there is a host o situations (in teaching or in courts, or

example) where it may be legitimately argued that or proessional and related rea-

sons there is a need or speakers to have access to one and others acial expression.27

23 Available via hp://www.guardian.co.uk/science/the-lay-scienst/2011/apr/12/2

[accessed 2 November 2011]24 See also her response to comments on her article: hp://opinionator.blogs.nymes.

com/2010/07/15/beyond-the-veil-a-response/ [accessed: 31 October 2011].25 Moors 2009passim surveys the arguments on the veil as an obstacle to communication;

also Bakht 2009, Mistry et al 2009, Schwartzbaum 2011.26 It has long been established in the discipline o linguistic anthropology that appropriate

orms o communication vary between cultures including social class cultures andthere are dierent, culturally and socially dened norms and practices concerning howand with whom one should communicate.

27 See Azmi v Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council[2007] I.C.R. 1154 (discussed by Hill

2011) where the suspension o a schools bilingual support worker who wore a veil was

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/the-lay-scientist/2011/apr/12/2http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/15/beyond-the-veil-a-response/http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/15/beyond-the-veil-a-response/http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/15/beyond-the-veil-a-response/http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/15/beyond-the-veil-a-response/http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/the-lay-scientist/2011/apr/12/2 -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

25/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 25

Under those circumstances the veil may well be considered an obstacle to interaction

between teachers and pupils, judges and counsel, juries and witnesses. This is widely

accepted and recognized as a potential problem.28 The arguments or and against

permitting veiling in a courtroom, or example, and possible solutions to overcome

any problems, are examined in detail by Bakht (2009; see also the Judicial Studies

Boards guidance to British judges, 2010, at 3.3). A pragmatic, situation-by-situation

approach rather than a blanket ban has also been advocated by the Secretary Gene-

ral o the Council o Europe, Thorbjrn Jagland.29

Objections about transparency and communication overlap with the reaction

some people experience in interpersonal encounters (casual, in the street, or in more

ormal circumstances) with women wearing the veil (or, or example, when some

Muslims, men as well as women, reuse to shake hands). Moors and Salih (2009:377) comment that Muslims engaging in devotional practices that are publicly vis-

ible such as wearing covered dress, engaging in prayer, and not shaking hands with

the opposite sex always need to take into consideration how the majority society

has already dened them. The response o those conronted by such practices may

range rom slight personal discomort (or mild embarrassment) to horried rejection

and outright rage, either at the practice itsel or what it is taken to represent (Moors

2009).30 There are, o course, many ways o dressing or presenting the body (think o

punks), which may cause others to experience personal discomort, but ew provokethe hostile, indeed visceral, response accompanied by demands or a ban that ace-

veiling does. As a blog comment by ACW on Martha Nussbaums New York Times

article (cited above) put it: I am startled by the number o posters who think that a

reasoned and upheld on the ground that communication with pupils would be impeded.In Germany, ace-veiling by school children is prohibited on the grounds that it inhibitscommunication.

28 In Norway, a proessor at the University o Troms required a student to remove herace-veil i she wished to attend his lectures, citing a recent parliamentary decision that

a teacher may request to see the ace o those who are taught. Fellow teachers mightwell sympathise with this point o view. But what kind o teaching context is involved?A large 100 plus lecture? A ace-to-ace tutorial? A seminar o 15 people? The issue ocommunication takes on a dierent shape in each o those contexts (hp://theforeigner.no/pages/news/norway-professor-imposes-niqab-veto/ [accessed 29 February 2012]). Ihe did not do so, it might have been interesting or the proessor to have talked the issuethrough with all other students in the group; were they all equally concerned?

29 hp://www.coe.int/t/secretarygeneral/sg/Opeds_jagland/20100707_burqa_en.asp[accessed 5 August 2011].

30 On negative eelings towards niqab-wearing women see hp://www.miller-mccune.com/

culture/negavity-and-the-niqab-36049/ [accessed 1 November 2011].

http://theforeigner.no/pages/news/norway-professor-imposes-niqab-veto/http://theforeigner.no/pages/news/norway-professor-imposes-niqab-veto/http://www.coe.int/t/secretarygeneral/sg/Opeds_jagland/20100707_burqa_en.asphttp://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.miller-mccune.com/culture/negativity-and-the-niqab-36049/http://www.coe.int/t/secretarygeneral/sg/Opeds_jagland/20100707_burqa_en.asphttp://theforeigner.no/pages/news/norway-professor-imposes-niqab-veto/http://theforeigner.no/pages/news/norway-professor-imposes-niqab-veto/ -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

26/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0526

valid argument or banning the burqa is that it makes THEM uncomortable. Basi-

cally, i someone elses attire whether a burqa or bikini makes you uncomortable,

it is your problem.31

Straw and Hollobone are among many who believe that as an obstacle to com-

munication, the veil also impedes integration. Indeed, many would go urther and

see it as a symbol o Muslim nonintegration (Meer, Dwyer and Modood 2010:

101). The case o Madame M, above, is telling in that respect. Citing witnesses, the

Commission Gerin observed that ace-veiling undermined conviviality, or the way

in which people might live together as a community. It was a symbol, and indeed

practical expression, o the ailure to integrate on the part o those women who wore

it (and o those who encouraged or obliged them to wear it), and put in question

basic French republican principles: liberty, equality, raternity. It thereore signiedthe dangers inherent in a society o parallel lives and o sel-enclosed communities.

Such concerns have been widely expressed elsewhere, notably in Germany, where

the phrase parallel lives was rst disseminated, and in the UK, ollowing the reports

into disturbances in Northern English cities in 2001: Britain, it was argued, was

sleepwalking to segregation, as Trevor Phillips, then Chairman o the Commission

or Racial Equality, put it (2005). Although the British Government has not thus ar

entertained a ban, the United Kingdom Independence Party, among others, claimed

that it should, as ace-veiling is divisive,32 and Phillip Hollobone justied his privatemembers Bill similarly.

There is, however, another side to this ailure to integrate, which is constituted

by the receiving societys own ailure to make space or deeply held belies and prin-

ciples and the practices that they authorize. In some cases (Belgium, France and

the Netherlands provide examples) not only is there a rejection o accommodation

but also an increasingly deep-seated hostility to other non-dominant belies and

practices. No wonder, then, that the women interviewed by Parvez (who included a

signicant number o Muslim converts) constituted a community huddling together,trying to protect itsel (2011: 298).

31 Available via hp://opinionator.blogs.nymes.com/2010/07/11/veiled-threats/ [accessed22 October 2011]

32 hp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_polics/8464124.stm[accessed 1 November 2011]

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/11/veiled-threats/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8464124.stmhttp://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8464124.stmhttp://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/11/veiled-threats/ -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

27/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 27

(e) Subjugation and Agency

Some o the most infuential arguments against ace-veiling and or a ban, which

inter alia refect concerns that it runs counter to our culture, relate to the posi-

tion o women that veiling is believed to symbolize. Indeed, Yasmin Alibhai-Browns

opposition to the veil, and that o many others, eminist and non-eminist, is largely

couched in such terms, as the earlier quotation rom Geert Wilders also shows. Face-

veiling, it is contended, is an assault on womens dignity;33 it is a symbol o patri-

archal authority and o emale subservience to men. The niqab and the burqa are

oppressive dress codes that are regressive as regards the advancement o women in

our society, said the sponsor o the Face Coverings (Regulation) Bill, Phillip Hollo-

bone in the House o Commons (Hansard, 11 March 2010, cols. 483-4). Moreover

women, it is argued, are requently coerced into wearing the veil by athers, brothersor husbands, and the involuntary acceptance o the practice is a serious inringement

o their human rights. Thus, the veiled Muslim woman, says Mullally (2011: 35), is

positioned as an abject victim, incapable o autonomy or agency, or conversely, as a

dangerous, threatening undamentalist.

Undoubtedly, moral or other coercion to veil may occur, though whether this is

best tackled through criminalizing the wearing o a orm o dress is questionable

(Werbner 2007). Idriss (2006: 430), writing about the Begum case, notes that some

young women were worried that i wearing the jilbab (a body-covering garmentwhich the applicant claimed was her right) were to be permitted in schools, they

would ace pressure to adopt it even i they did not wish to do so. Dwyer (1999: 12)

too contends that:

Young men, in particular, oten played an active role in monitoring and censuring emi-nine appearances. This monitoring o eminine dress and behaviour is closely associatedwith rural Mirpuri codes o amily honour or izzat, which place considerable emphasison women as the guardian o amily integrity.

On the other hand, as Abu-Lughod reminds us, veiling itsel must not be conusedwith, or made to stand or, lack o agency (2002: 786). There is considerable evidence

that headscar and veil-wearing is increasingly and reely adopted by many young

Muslim women in Europe (e.g. Bowen 2007: 256),34 despite the pressure not to veil

33 On the trope o emale dignity in the debate in France, see Dumouchel 2010, Joppke 2011,Mullally 2011, and Vrielink and Brems 2011, or Belgium.

34 This point is made strongly by, among others, Hind Ahmas, one o the rst French womento be prosecuted or wearing a ace veil: hp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9nqmyHjPlU

[accessed 1 November 2011]. See also hp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0h1zuwpFdo4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9nqmyHjPlUhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0h1zuwpFdo4http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0h1zuwpFdo4http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9nqmyHjPlU -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

28/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-0528

on the part o mothers or athers, or through ear o encountering public hostility

(Dwyer 1999). All o the women I met in the mosque community o Les Minguettes

[Lyon], says Parvez (2011: 289), reely chose to wear the djelbab or niqab, sometimes

even against the wishes o their husbands and amilies, and cites the case o Amina

whose amily mocked her religious practice and oered her no material or other

support (p. 298).35 Such women experience diculty in having their voices heard in

a media dominated by the trope o Muslim womens oppression and subordination

to patriarchy (Moors 2009).

Womens claim that it is their decision to veil (in accordance with their religious,

social and cultural belies and practices) is, however, requently dismissed as an inad-

equate response. Choice cannot be the only consideration, says Yasmin Alibhai-

Brown (2011):

And anyway, there is no evidence that all the women are making rational, independentdecisions. As with orced marriages, they cant reuse. Some are blackmailed and othersobey because they are too scared to say what they really want. Some are convinced theywill go to hell i they show themselves. Some bloody choice.

Despite Abu-Lughods cautionary observation, it remains the case that law-making

is done on the basis o dominant assumptions about minority cultures and their

members views, with the minority being treated as a silent interlocutor, or called

upon to testiy on the basis o questions asked within, and debates occurring within,

Western culture. As Rosa lvarez Fernndez comments (2011; see also Taha 2010):

The controversy [in Spain] shows there is no dialogue among ellow citizens with dierentreligions and sources o identities. Instead there is a monologue o the dominant societyabout their own prejudices and its ears o Islam, the meanings o secularism, identityand the limits o tolerance. The hijab case tells us more about Spanish society than Mus-lims themselves.

() Identifcation and Security

A nal set o objections to ace-veiling concerns identication and security. Under

certain circumstances, it is argued, it is necessary to establish that the veiled person is

(CNN discussion with Mona Eltahawy and Hebah Ahmed), and videos availableon hp://muslimmaers.org/2011/04/12/cnn-hebah-ahmed-muslimmaers-blogger-debates-mona-eltahawy-over-french-niqab-burka-ban/ [all accessed 30 November 2011].See also Rozario 2006 on women adopters o the niqab in Bangladesh.

35 See also hp://www.the-plaorm.org.uk/2010/02/14/the-hijaab-20-years-on/ [accessed1 November 2011]

http://www.the-platform.org.uk/2010/02/14/the-hijaab-20-years-on/http://www.the-platform.org.uk/2010/02/14/the-hijaab-20-years-on/ -

7/31/2019 WP 12 05 Grillo Reasons to Ban

29/48

Grillo / Shah: The Anti-Burqa Movement in Western Europe / MMG WP 12-05 29

who she claims to be. This might be the case in a bank, or example, or when some-

one is seeking welare benets, or voting in an election. As with appearance in courts,

these are particular situations in which special provision may be made to ascertain