Wood et al. - Case Report Collapse , reported seizure — and an unexpected pill.pdf

-

Upload

matildameister -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Wood et al. - Case Report Collapse , reported seizure — and an unexpected pill.pdf

-

8/12/2019 Wood et al. - Case Report Collapse , reported seizure and an unexpected pill.pdf

1/1

Case Report

1490 www.thelancet.com Vol 369 April 28, 2007

Collapse, reported seizureand an unexpected pill

David M Wood, Paul I Dargan, Jennifer Button, David W Holt, Hanna Ovaska, John Ramsey, Alison L Jones

In May, 2006, on a Bank Holiday weekend, an 18-year-oldwoman presented to an inner-city London emergencydepartment. She had been at a nightclub with friendsand purchased tablets, which she understood to beEcstasy or amfetamines, from a dealer. After ingestingfive tablets, she collapsed in the nightclub and appearedto have a seizure lasting 10 min. On arrival in theemergency department, she was agitated and had dilatedpupils (8 mm), sinus tachycardia (156 bpm), and a bloodpressure of 150/51 mm Hg. Her score on the Glasgowcoma scale was 15 and she was apyrexial (359C). She

had no significant past medical history and was on noregular medication.

She was one of seven patients to attend the departmentthat night with a similar presentation. We thereforeconsidered it possible that she had taken a contaminateddrug, or a substance not previously sold in the area; and wetook a serum sample for analysis, in addition to treatingthe patient symptomatically with intravenousbenzodiazepines (4 mg lorazepam followed by 15 mgdiazepam). After 12 h, she was asymptomatic anddischarged with advice to avoid recreational drugs. Theserum sample was analysed by gas chromatography withmass-spectrometric detection (GCMS); 1-benzylpiperazine

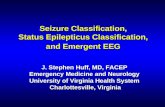

was detected at a concentration of 25 mg/L. Toxicologicalscreening of the same serum sample did not detect thepresence of other piperazines, other drugs, or ethanol. Atablet purchased by the patient (figure) was also analysed,and found to contain 1-benzylpiperazine.

1-benzylpiperazine is one of the piperazine family ofdrugs, initially developed as veterinary anthelmintic agentsin the 1950s. Its chemical structure is similar to that ofamfetamine.1Piperazines are marketed in the UK, wherethey are legally available in shops and over the internet, ashaving similar effects to controlled recreational drugs; pills

containing piperazines are known as pep pills.2 Noreliable data are available on the consumption of piperazinesin the UK, although one manufacturer claims that over20 million pills have been consumed in New Zealand withno deaths, or significant lasting injuries.2 However, ininitial clinical trials of 1-benzylpiperazine, adverse effectssimilar to those of amfetamines were noted.3A prospectivestudy in New Zealand identified adverse effects includingnausea, vomiting, tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, andagitation among 80 patients presenting to emergencydepartments after 1-benzylpiperazine ingestion.4 Seizureswere reported in 15 (19%), at up to 8 h after ingestion. Threepatients had potentially life-threatening recurrent seizures;

ingestion of 1-benzylpiperazine by these patients wasconfirmed by toxicological screening of their urine. Otherpotentially serious adverse effects included QTcprolongation (QTc duration 430490 ms in 32 patients) andhyponatraemia (serum sodium concentration 118 mmol/Land serum osmolality 242 mmol/kg) in one patient.Clinicians should be aware of the potential presentingfeatures of piperazine toxicity, particularly becausecommercially available urine toxicological screening kitsfor drugs of abuse may not detect piperazines. All patientswith strongly suspected or reported ingestion of1-benzylpiperazine should have an initial baseline ECG, toseek features of cardiotoxicity. They should be observed forup to 8 h after ingestion, because the onset of seizures can

be delayed. Initial treatment should be based on the clinicalpresentation. Further management can require the adviceof a clinical toxicologist.

References1 Wikstrom M, Holmgren P, Ahlner J. A2 (N-benzylpiperazine) a new

drug of abuse in Sweden.J Anal Toxicol2004; 28:6770.

2 Spiritualhigh.co.ukStaying safe on PEP pills. http://www.spiritualhigh.co.uk/information/drug-harm-minimisation-and-legal-highs/staying-safe-on-pep-pills/3-7-7-19 (accessed April 2, 2007).

3 Bye C, Munro-Faure AD, Peck AW, Young PA. A comparison of theeffects of 1-benzylpiperazine and dexamphetamine on humanperformance tests. Eur J Clin Pharmacol1973; 6:16369.

4 Gee P, Richardson S, Woltersdorf W, Moore G. Toxic effects ofBZP-based herbal party pills in humans: a prospective study inChristchurch, New Zealand. N Z Med J2005; 118: U1784.

Lancet2007; 369: 1490

See Commentpage 1411

Department of Clinical

Toxicology, Guys and St

Thomas Poisons Unit, London

SE14 5ER, UK(D M Wood MD,

P I Dargan FRCPE, H Ovaska MD) ;

Analytical Unit(J Button MSc,

Prof D W Holt FRCPath) and

TICTAC Communications Ltd

(J Ramsey), St Georges

University of London, London

SW17 0RE, UK; and Faculty of

Health, University ofNewcastle, NSW 2308,

Australia(Prof A L Jones MD)

Correspondence to:

Dr David Wood

CH2

NH2

CH3CH

CH2 N N H

A

B

1-benzylpiperazine

Amfetamine

Figure: 1-benzylpiperazine

(A) One of the tablets purchased by the patient. (B) 1-benzylpiperazine and

amfetamine.