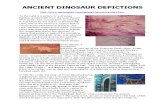

WOMEN & RELIGIOUS ART: GENDER DEPICTIONS IN THE ...

Transcript of WOMEN & RELIGIOUS ART: GENDER DEPICTIONS IN THE ...

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

159

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

WOMEN & RELIGIOUS ART: GENDER DEPICTIONS IN

THE RENAISSANCE ERA

Georgie Ann Weatherby, Ph.D.

Gonzaga University

ABSTRACT

Women throughout religious history have been commonly depicted as adornments to men, adoring nurturers

who rarely express a personal opinion, while staunchly supporting the views of those males central to their

lives. To fulfill a warrior role of power and leadership strongly contests this gentle, calming influence so

typically associated with the “instinctual” female. Feelings of anomie can be the impactful result for the

recipient. This leads to the following questions: How are women truly projected via religious art in

Renaissance times? Do they defy the image of the familial centerpiece? Do they instead embrace that

norm? Female reflections are analyzed in Renaissance art wherever representations figure at least

somewhat prominently. The location selected for study resides in Florence, Italy: The Accademia Museum.

What results thereafter is a discussion of the feelings of anomie (but also of progress/feminization) that arise

from disconcerting views of women as expressed in celebrated art forms, even if those are not the concerted

norm for this fruitful artistic period.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout the ages, the expectations of artistic likenesses of the female have been often equated

with gentle, softly hued, maternal subservience (Chadwick, 1996; Tinagli, 1997). Women warriors

with hardened hearts and fierce exteriors to match are thought to be the uncommon exception

(Weatherby, 2014; Weatherby, 2015). When placed on equal footing with men (or even superior to

them), the viewing audience is predicted to respond in shocked disbelief (linked directly to Emile

Durkheim‟s concept of anomie – Durkheim, [1897] 1966). This occurs where the human receptacle

(recipient) is placed in sensory overload, reacting with a mixture of: 1.) Confusion with an image

so frightfully contrary to the traditional norm and 2.) A mad dash at that same moment to bring

about order where one‟s familiar structure has been shaken to its core – explaining away the visual

as a simple anomaly, or a slap in the face of normalcy. Because of this anticipated negative

response, the standard prediction is that such depictions of female prowess would be rarities, at

best.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

160

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

LITERATURE REVIEW

As a window into Italian society during the Renaissance, it is contended “poetry stammers and

eloquence grows dumb, unless art serve as interpreter” (Cropper, 1976:394; Masters, 2013).

Galileo (1953) furthers this sentiment: “All things are easy to understand once they have been

discovered… The point is in being able to discover them.” Visuals of the period, mostly crafted by

men, tend to feature males in dominant, central positions, sometimes to the exclusion of women

altogether. When the female is portrayed, the intent is to convey beauty and social role

(Anonymous, 2017). Lorenzo the Magnificent described such ideal Renaissance beauty as a

woman “of an attractive and ideal height; the tone of her skin, white but not pale, fresh but not

glowing; her demeanor grave but not proud, sweet and pleasing, without frivolity or fear. Her eyes

were lively and her gaze restrained, without trace of pride or meanness; her body so well

proportioned, that among other women she appeared dignified… in walking and dancing… and in

all her movements she was elegant and attractive; her hands were the most beautiful that Nature

could create. She dressed in those fashions which suited a noble and gentle lady…” Although the

word “portrait” in Italian, ritratto, is translated as “copy,” the artist often sought only to imitate the

beautiful aspects of nature and to flatter the subject (Christiansen, Weppelmann, and Rubin, 2011).

Christiansen et al. (2011) further elaborated that in addition to equal proportion and perfect

symmetry, subjects possess blonde hair, high forehead, ruby lips, and fair skin – all indicative of the

ideal Italian beauty. Firenzuola shows how this is akin to the proportions of an antique vase…

„with its long neck rising delicately from its shoulders… or one with sides that swell out around a

sturdy neck making it appear more slender… resembling the ideal, fleshy-hipped woman, who

needs no belt to set off her slender midriff‟ (Cropper, 1976: 377). Inner beauty is expected to

complement this outer form. This is best expressed as a telegraphing high moral standards

exemplified as modesty, humility, piety, constancy, charity, obedience, and chastity (Brown, 2001;

Masters, 2013).

Hence, it can be determined that art is a direct vehicle by which we can gauge the society it

represents (West, 2004). Renderings of Renaissance women are no exception. One would expect

to encounter serenity of looks pleasing to the eye and finery of attire to match, figures embodying a

typical wealthy leisure class of comfort. However, is this all that can be anticipated of the art? The

literature makes little mention of femininity in terms of maternal role. After all, ruling class

families are assumed to employ nannies to concentrate on such mundane daily tasks. Also, would

there be no emphasis on nontraditional females, warriors and orators alike? These women battle for

equality, justice, and their deep faith. Nevertheless, are they nonexistent among Renaissance

figures as captured by the artists of their day? The present study seeks to untangle these mysteries.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

161

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

DATA & METHOD

In order to test this assumption, the opposite assertion is posed. The womanly figure is allotted

more credit for her worldly contributions. Strong poses exhibiting battle skills, which bow to no

one, seem to be the anomaly. A complete cataloguing of Renaissance images (mostly in painting

form, but all are included) on display in the famed Accademia Museum in Florence, Italy will be

fully analyzed. The total number of artistic cases (male, female, mixed, angelic, animals, and

nonhuman in terms of musical instruments, etc.) is 247, as captured in in a visual assessment of the

entire contents of the museum, with extensive notes recorded. These were then corroborated with

the comprehensive guidebook of the facility: Accademia Gallery: The Official Guide – all of the

works (Accademia Gallery, 2015) and the secondary guide: Accademia Gallery: Masterpieces and

More (Sillabe, 2007), to ensure accuracy of the findings. These results include panels with smaller

inserts as separate entities for the purposes of this research. Those featuring females in central roles

is estimated at 121, or just under half of the collection as a whole. As an inter-coder reliability

check, a systematic sample (Champion, 2006) of every 8th

case was drawn for a Masters of Divinity

Theologian (retired Diocesan Catholic Priest) to rank blindly. Comparisons were then reviewed,

and the interpretations were adjusted accordingly.

The data collected on each are described in detail and coded in Appendix A, with results presented

in Appendix B. While there are a number of female images pictured at the center of the home

(deemed “traditional female image,” N = 32) and/or crib (labeled as “maternal image,” N = 89),

others depict variances on this theme. “Nongendered in afterlife” angels on high exist in heavenly

roles, exerting influence over earth in some special or even supernatural way (“elevated status of

angels (nongendered),” N = 33). “Elevated status of female(s)” (most often indicating the stature of

Sainthood, N = 32) are another direction in which women move. Portrayals of women in battle or

at the helm of some form of leadership role (“nontraditional female image”) are less in number (N =

16), but are contended to be some of the most striking (and alarming) pieces in the collection.

RESULTS

Of the artistic product population, 32 fulfill the traditional female image role. During the

Renaissance period, this attribution is to be fully anticipated. According to Weatherby (2015), the

woman is most often deemed fragile, docile, and for the most part, without opinion (speaking when

spoken to, in other words). When a female image reverses this impression, the societal reception is

shock and even repression. She knows not her place. She will undoubtedly pay down the line for

her brash assumption of equality and intellectual value for herself.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

162

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

This leads to the next category, which is related in nature, of the maternal female image status, with

89 cases recorded. Women bear children, raise them, and frequently occupy the role of adoring

them, when necessary. The male maintains a certain level of distance during the Renaissance, but

coincidentally at most other moments in historic memory as well. The division of labor is set and

undisputed. The woman is internal to the home. The man is external – conquering the world in

terms of hunting, battle, and outward social expectations. These artistic renderings capture a strong

parceling of chores, with no crossover allowed or even tolerated, for the most part (such as a male

sharing in child care responsibilities, for instance).

The third category is a natural progression stemming from the first two. In 33 cases of artistic

representations, previous worldly figures both male and female are rendered to an elevated status of

angels (post-life, nongendered). Like stereotypical women, pure in life (not touched by the sins of

cigars, brandy, and wild thoughts as well as deeds), most angels are depicted as soft, gentle,

calming spirits of divine influence. They hover, they bless, and they console earthly beings (male

and female, alike). They are eternal, and appear as a stable force in an often-turbulent earthly

world. Painted in soft, glowing whites and creamy, comforting pastels most often, they provide

solace, and promote belief in a rewarding afterlife (Richardson & Weatherby, 1983). They are

several rungs above blissful happiness on the steep ladder to eternity. They embody paradise, and

all we wish to know, but only have a hint of from these artistic glimpses, genderless as they are.

Next, females are displayed in an elevated status as saints in 32 artistic depictions. This is the

ultimate pedestal for which to vie. Whether featured in the flesh or as a vision, women categorized

as saints are deemed miraculous at least three times over, which is the same requirement met by

men who receive this elevated status. These women have a specialty, as do all saints. Saint

Catherine of Alexandria is featured most often and most prominently among female saints adorning

the collection at the Accademia Museum. Born in 287 A.D. in Alexandria, Egypt and martyred

around 305 A.D., she was persecuted for converting everyone she encountered to Christianity (and

most famously, even those sent to derail her). A vivid vision of Jesus and Mary converted her at

age 14. She won all debates with philosophers and orators, pagans each of them, who disputed her.

Many of them converted to Christianity because of this contact. They were subsequently put to

death. Eventually refusing to marry the emperor who set up the debates (she claimed a virgin union

with Christ), he condemned her to death on the breaking wheel (a torture instrument of great

repute). One simple touch of it by her shattered it. She was beheaded soon after. Her body was

discovered around the year 800 at Mount Sinai (where the angels had left her corpse). It was

incorrupt (lacking decay). Her hair was still growing, and a steady stream of healing oil flowed

from her body. The fluid was captured to include with relics at various gravesites where pilgrim

believers are said to be miraculously cured of their ailments. A series of documented miracles have

led to her canonization in the Catholic Church. To this day, before studying, writing, or preaching,

many seek Saint Catherine of Alexandria to illuminate their minds. At the instant of her death, she

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

163

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

entreated Christ to answer the prayers of all who honor her martyrdom and invoke her name

(Author Unknown, 2017; Catholic Online, 2017; Walsh, 2007). Patrons include unmarried girls, all

who craft with a wheel (potters and spinners), archivists, dying people, educators, jurists, lawyers,

librarians, hat-makers, nurses, philosophers, scholars, and scribes, among numerous others (Freze,

1992).

In brief, we equate the life of a saint with inordinate power, beyond the capabilities of mere mortals.

Now, they work on our behalf when we invoke their spirit by calling on them when their special

expertise is of necessity (on most frequent occasions in the form of concerted prayer).

This leads to the final category of nontraditional female images (with the lowest number of cases

observed, N = 16). This is the real life warrior in the most favorable light, and “Death Herself”

(please see the Saint Mary Magdalene panel in Appendix A) in the least favorable. Most artistic

works embrace the former, The Allegory of Fortitude being the ultimate model (again, found in

Appendix A on Floor One in the gallery). This painting, by Tommaso Manzuoli detto Maso da

San Friano (circa 1560-1562), is an oil on wood masterpiece that captures the dominance of a

partially disrobed commanding female figure seated at the forefront in giant, imposing form, having

successfully tamed a lion now docile beneath her firmly planted right foot. She is holding a lethal

studded mace, while a diminished Hercules struggles in the background, losing miserably to yet

another lion. The message rings clear. This woman is an undefeated, undisputed warrior queen

with whom no one dare take issue – not wild animals that tear mere mortals to pieces, not men

reputed to be superhuman, not even the forces of nature – be they destructive winds, oscillating

oceans, fervent fires, or a parched, barren earth. Lady Fortitude is firmly in control. All forces bow

to her, and in return, she offers shelter to those indebted to her uncanny power. Men and women

alike aspire to emulate her. She is elevated above humanity and therefore may pose little threat to

humankind. Fortitude is a perfect embodiment of women elevated and empowered by art forms.

Are they a threat to the status quo? Alternatively, are they simply the female equivalent of

Michelangelo‟s Statue of David (1501-1504)? Larger than life, he is a giant-slayer (victorious over

Goliath not due to brute force, but his success entirely attributed to his intellect and innocence). He

represents courageous perfection in his own right. He is what most everyone wishes to aspire to in

terms of heroic valor. Perhaps not by chance, The Allegory of Fortitude is positioned on Floor One

of the Accademia Museum to keep an eye on David (just across the room to his left, tucked near a

corner) and he in turn can cast his focused gaze on her. Though she is born well after his time, they

are undisputed warriors, both. It could be argued that they occupy equal ground in terms of their

outward and inner power.

Fortitude is startling when compared to the status of many of the other females captured – in their

traditional, maternal roles, or even those of elevated status in terms of angelic likenesses or saintly

figures. To be depicted as “Death” is much less common, and perhaps most anomic of all, as it is

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

164

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

anti-feminine and some would say vile in its very portrayal. The fact that such cases are a relative

rarity is to be predicted. When confronted with such images, the tendency is to react in dismay and

perhaps even stern disapproval. In the Renaissance Era, and those before and beyond, viewers are

most at ease with traditional, maternal, revered (saintly/angelic) versions of the female gender.

These cause no cognitive dissonance, no need to reappraise the role of the female in greater society.

They stave off the considerable anomie created by nontraditional female images. Yet, if an artist in

any period seeks enlarged impact, then ripping the audience from their familiar cocoon of

expectation holds the strongest guarantee of not only immediate effect, but also lasting memory.

SUMMARY/CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, the Accademia Museum holds the most in terms of female art that is maternal in

nature. Though not heavily highlighted in the previous literature, this is to be expected, as the

woman‟s prime responsibility was rooted in her power to bear and raise offspring. Next in volume

are angelic portrayals. Since they are without gender, and are cast as sinless, they are often equated

with feminine traits, such as gentle selfless kindness. Traditional female images follow in number,

cast most frequently in the home‟s library or sitting room, with intriguingly few displaying work in

the kitchen or any other mundane domestic duty (though the ruling class subjects were likely

dependent on servants to fulfill such roles). Even in number with traditional depictions are females

of elevated status, and with very few exceptions, being honored as saints in their own right. This

positions them among males also elevated for their miraculous feats. These are commonly judged

by their healing powers after death – invoked through concerted prayers, or at the physical gravesite

itself, or at a spot where a relic is located. Those miracles must be documented, and at least three in

number to qualify for consideration of canonization. Finally, at the lowest number, nontraditional

female figures are present in the collection. Depicted in full warrior mode is The Allegory of

Fortitude. Captured as alluring images of beauty and reserve, is the most prolifically painted Saint

Catherine of Alexandria, whom we study further to discover as a true warrior within. She gave the

ultimate sacrifice in the end – her life for her cause (Christianity). We are similarly moved by these

two likenesses. They give life to the often one-dimensional pose of a woman, expanding her

exponentially in deeds and potential, along with the respect not only demanded, but also earned

among fellow artists, historians, and the viewing public.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

165

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

A poem captures it best:

A Place in Time

Images of angel art, women soft with grace.

Portraits laced with merriment, the Renaissance, the place.

Dashing men, the sworded type, sweet honor, they defend.

Ladies stare with charmed content, warriors fierce, pretend.

Saint Catherine of Egypt fair, blessing all who spoke.

She gave her life, a bride of Christ, her name, we still invoke.

by G. Weatherby

DISCUSSION

It can be determined throughout the analysis that feminist images to varying degrees in the

Renaissance Era are somewhat more likely to appear than the historic period would merit by its

projected attitude toward and concerning women. The result then as well as now is often one of

shock (Durkheim‟s anomie, 1897/1966). In comparison to contemporary American art, these types

of exceptional images stand with firm justification. For instance, Rosie the Riveter (Rockwell,

1943) in poster and magazine cover art signified the strength of women fulfilling traditionally male

working roles in shipyards and factories while the majority of men were off at war (WWII)

defending our country and the freedoms of the world. Rosie (fashioned after an actual worker at the

time) is strong, resilient, and exudes self-confidence. You can imagine her besting Hercules and

taming the wildest of animals, had she instead found herself rising up in Renaissance times. Baring

one‟s muscular arm during WWII is the G-Rated version of Fortitude‟s exposed breasts… nothing

to hide and nothing to fear. The woman depicted in each case is fierce, and here to stay. “Strong

woman art” (Weatherby, 2017) is the lasting result.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

166

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

REFERENCES

Anonymous (no author listed)

2017 Gender in Art: The Renaissance and The Baroque. Online source.

Author Unknown

2017 Lives of Saints – Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint, Virgin, Martyr.

Online source.

Accademia Gallery

2015 The Official Guide – all of the works. Prato, Italy: Giunti.

Brown, David Alan

2001 “Introduction.” In Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginerva De’Benci and

Renaissance Portraits of Women, by David Alan Brown:12-21. Washington:

National Gallery of Art.

Catholic Online

2017 St. Catherine of Alexandria – Saints & Angels.

Chadwick, Whitney

1996 Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson.

Champion, Dean John

2006 Research Methods for Criminal Justice and Criminology, 3rd

Edition. City:

Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Christiansen, Keith, Stefan Weppelmann, and Patricia Lee Rubin

2011 “Understanding Renaissance Portraiture.” In The Renaissance Portrait:

From Donatello to Bellini, by Keith Christiansen, Stefan Weppelmann, and

Patricia Lee Rubin, 4. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cropper, Elizabeth

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

167

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

1976 “On Beautiful Women, Parmigianino, Petrarchismo, and the Vernacular

Style.” Art Bulletin:374-394.

Durkheim, Emile

[1897] 1966 Suicide: A Sociological Study. New York: Free Press.

Freze, Michael

1992 Patron Saints. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division.

Galileo

1953 Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems – Ptolemaic and

Copernican. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Masters, Rachel D.

2013 The Portraiture of Women During the Italian Renaissance. Honors

Manuscript: University of Southern Mississippi.

Manzuoli, Tommaso

1560-1562 The Allegory of Fortitude. Florence: Accademia Museum.

Michelangelo

1501-1504 The Statute of David. Florence: Accademia Museum.

Richardson, John G. and Georgie Ann Weatherby

1983 “Belief in an Afterlife as Symbolic Sanction.” Review of Religious Research,

Vol. 25, No. 2 (December): 163-170.

Rockwell, Norman

1943 “Rosie the Riveter.” Saturday Evening Post Cover Art. May 29.

Sillabe

2007 Accademia Gallery: Masterpieces and More. Firenze: MVSEI.

Tinagli, Paola

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

168

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

1997 Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, and Identity.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Walsh, Christine

2007 The Cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria in Early Medieval Europe. New

York: Ashgate Publishing.

Weatherby, Georgie Ann

2017 “Strong Woman Art.” Lecture topic. Spokane: Gonzaga University.

Weatherby, Georgie Ann

2015 “Going Against the Grain: The Power of Women in Italian Renaissance Art,

Greek and Roman Mythology, and the Modern Day Middle East.”

International Journal for Research in Social Science and Humanities, Vol. 1,

Issue 2 (December).

Weatherby, Georgie Ann

2014 “Daring the be Different: The Impact of Positive Deviance on the Global

Stage.” Voyages: Rethinking Nature and its Expressions, Gonzaga

University in Florence Press, Summer.

(http://www.voyagesjournal.net/Essay_Weatherby.html)

West, Shearer

2004 “Gender and Portraiture.” In Portraiture, by Shearer West: 21-41. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

169

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

APPENDIX A

Art with Female and/or Angelic Depictions Present – Accademia Museum – Florence, Italy

(2015)

FLOOR ONE:

The Visitation – Saint Anne portrayed by Pietro Perugino (1472-1473) – elevated status of

female (Saint)

Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels by Alessandro Botticelli

(1470) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Madonna and Child with Saints Anthony, Louis, Francis, Jerome, Bernardino, and Sebastian

by Maestro Degli Angeli di Carta (1470) – maternal image

Crowning of the Virgin (surrounded by angels) by Maestro dell Epifania di Fiesole (1470-

1480) – maternal image/traditional female image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Assumption; Portrait of don Biagio Milanesis/Portrait of Monk Baldassarre (angels abound)

by Pietro Peragino (1500) – elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Deposition from the Cross by Filippino Lippi and Pietro Perugino (1503-1507) – traditional

female images

Nativity; Four Prophets by Maestro della Nativita di Castello (1460) – features Madonna

and Child and Angels – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Saint Mary Magdalene Panel by Filippino Lippi (1496) – arms crossed, female appears

death-like – nontraditional female image

Saint Monica by Francesco Botticini (1475) – hands clasped, contrite nature – elevated

status of female (Saint)

Saint Francis, Saint Philip, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Saint Jerome, Bishop Saint by

Neridi Bicci (1450) – Saint Catherine with plume and Bible in hand – nontraditional female

image/elevated status of female (Saint Catherine)

Madonna and Child and the Christ as the Man of Sorrows by Andrea di Giusto Manzini

(1435) – angels above mother and child – Madonna holding sprig of flowers with Christ in

arms – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

170

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Adoration of the Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist by Gherado di Giovanni

(1485) – with angels above and Saint John the Baptist in child form, Madonna prays over

Christ child – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Madonna and Child Crowned by Two Angels and Workshop by Cosimo Rossellie Bottega

(1490) – angels above and at sides – Christ child stands on golden pillow with Madonna

gingerly embracing him – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Martyrdom of the Teeth (pulling them from woman by men); Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia

(ready for beheading by men – one with axe, and five others looking on closely) by

Francesco Granacci (1530) – anomic elevated status of females (martyrs/saints)

Christ as Man of Sorrows with Virgin and Saint John by Pittore Fiorentino (1490) –

maternal image/traditional female

Adoration of the Child by Pseudo Pier Francesco Fiorentino (1475) – maternal image

Angel of Annunciation; God the Father; Virgin of the Annunciation by Biagio d ‟Antonio

(1475) – maternal image/traditional female image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Adoration of the Christ Child by Lorenzo di Credi (1480-1490) – all women praying for

Christ child – traditional female images

The Deposition and Saints James the Great, Francis, Michael, and Mary Magdalene by

Jacopo del Sellaio (1493) – traditional female image

Six Praying Angels by Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (1505-1508) – elevated status of angels

(nongendered)

Madonna and Child with Saint Joseph and Saint John the Baptist by Franciabigio (1508-

1510) – almost Mona Lisa look – head toward shoulder, thoughtful gaze over son below –

maternal image

Dispute over the Immaculate Conception by Giovanni Antonio Sogliani (1521) – dispute

among Doctors of the Church over Virgin‟s Birth as Free from Original Sin. Dead body of

Adam at the bottom – symbolizing Condemnation following Original Sin – maternal

image/traditional female image

The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Bernardo degli Uberti, George, Giovanni

Gualberto, and Catherine of Alexandria by Francesco Granacci (post 1520) – Catherine with

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

171

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

plume in hands looks up pensively – maternal image/elevated status of female

(Saint)/nontraditional female image

Saint Barbara and Saints John the Baptist and Matthew by Cosimo Rosselli e Bottega and

Workshop (1468) – warrior crumpled at feet of Saint Barbara/Saint Barbara with plume in

right hand, large structure in the other – elevated status of female (Saint)

Madonna and Child with Saints Dominic, Cosmas, Damian, Francis, Lawrence, and John

the Baptist by Alessandro Botticelli e Bottega and Workshop (before 1497) – maternal

image

Annunciation – by Maestro della a Nativita Johnson e Filippino Lippi (1475-1480) –

maternal image/elevated status of angel (nongendered)

Madonna of the “Cintola” with Saints Catherine and Francis by Andrea di Giusto Manzini

(1437) – Catherine has plume in left hand here – panels below: Saint Catherine – attached

to wheels; Transit of Virgin; Saint Francis receives the Stigmata – maternal image/elevated

status of female (Saint Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Statue – Rape of the Sabines by Giambologna (1582) – older man defeated by younger man

– later grasps woman in forceful gesture – offers “infinite viewpoints” – “rape” may be too

strong here – young man may be protecting woman from clutches of older man – traditional

female image

The Virgin of “Cintola” by Francesco Granacci (1508-1509) – Virgin ascends into heaven –

giving waistband to doubting Saint Thomas as proof of real presence – maternal

image/elevated status of female (heaven-bound)

Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Zenobius by Francesco Granacci (1508+) –

maternal image

Annunciation by Mariotto Albertinelli (1510) – maternal image/elevated status of angel

(nongendered)

Ideal Head by Michele di Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (1560-1570) – warrior woman – elevated

status of female

Ideal Head (second one – same artist and period) – profile of ancient Queen Zenobia, a

fearless warrior and strong, virtuous, beautiful woman – elevated status of

female/nontraditional female image

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

172

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Venus and Cupid by Jacopo Carrucci (cupid kisses Venus, 1533). Renaissance theory of

love: earthly love driven by senses (Cupid) and heavenly love (symbolized by Venus)

turned toward the divine – traditional female image

Madonna and Child with the young Saint John by Giuliano Bugiardini (1520) – Christ child

picks date from palm tree – offers it to Saint John (Madonna‟s hand in ballet form, fingers

curled as elegantly outstretched) – maternal image/traditional female image

Holy Family with Young Saint John the Baptist by Pier Francesco Foschi (1525-1535) –

Madonna only figure in frontal view, as if seated on a throne. Saint Joseph and young Saint

John frame her, on either side – maternal image

Allegory of Fortitude by Tommaso Manzuoli detto Maso da San Friano (Firenze, 1531-1571

– painted 1560-1562). Secular subject and unabashed nudity – warrior woman – elevated

status of female/nontraditional female image

The Immaculate Conception by Carlo Portelli (1566) – maternal image/traditional female

image

Santa Barbara by Pittore Vasariano (1550-1560) – imprisoned in tower by her father – he

was struck dead by lightning bolt of Divine Wrath – traditional female image

Allegorical Figure by Francesco Morandini detto il Poppi (1575-1580) – allegory of

“charity” – traditional female image

Madonna and Child, the Young Saint John, and an Angel by Francesco de Rossi detto II

Salviati (1543-1548) – maternal image/elevated status of angel (nongendered)

Deposition of Christ by Agnolo Tori detto n Bronzino (1560-1561) – no primary status of

females

Madonna Enthroned with Child, the Young Saint John, Saints Lucia, Cecelia, Apollonia,

Agnes, Catherine, Elisabeth and allegorical figures of the Active and Contemplative Life

(1575) by Alessandro Allori – maternal image/elevated status of females

(Saints)/nontraditional female image

Annunciation by Alessandro Allori (1578-1579) – Holy Spirit signified by golden light

raining down from above and multitude of flowers showering to the floor from angels‟

hands. Lily in Archangel Gabriel‟s hand = chastity and virginity‟s cornflower blue =

paradise; symbol of Christ = jasmine; broom yellow flowers emit scent only when touched

by the sun = Christ‟s Incarnation and the moment that Mary receives the Holy Spirit; tulip =

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

173

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

flower that dies without sun/symbolic of search for Divine Love and Virgin‟s suffering at

crucifixion of her son – traditional female image/maternal image/elevated status of angels

(nongendered)

Coronation of Virgin by Alessandro Allori (1593) – more botany – myriad of cut flowers –

maternal image/traditional female image

Deposition of Christ with the Virgin, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Catherine of Alexandria,

and the Patron by Santi di Tito (1592) – maternal image/elevated status of female (Saint

Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Deposition of Christ by Stefano Pieri (1587) – the body of Christ supported by the Virgin,

who is overcome by grief (signaled by facial expression and placement of left arm) – sense

of “desperate abandonment” – maternal image

Annunciation by Alessandro Allori (1603) – the Virgin, reading, opens arms wide, in

obedience to God‟s will – maternal image/traditional female image

Saint Peter Healing a Lame Man by Cosimo Gamberucci (1599) – woman only looking on

at side – traditional female image

STATUE ROOM RESTRICTED TO LIMITED VIEWING (corded off in February 2015– so

inability to circle and identify figures – also viewed one year prior, but not in data collection mode)

PANELS:

Madonna and Child by Pittore Fiorentino (1250-1260) – maternal image

Madonna and Child and Two Angels by Pittore Lucchese (1240-1250) – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Repentant Magdalene and Eight Stories of her Life by Maestro della Maddalena (128-1285)

– traditional female image

Painted Cross by Pittore Fiorentino (1285-1295) – at base of crucifixion, Mary Magdalene

mourns (tips of arms shortened, tiny figure in scale to giant Christ depiction – with bleeding

stigmata – feet, side, hands) – traditional female image

Madonna and Child with Saints (Paul and John the Baptist) by Grifo di Tancredi (1271 to

1303) – maternal image

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

174

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Madonna and Child Enthroned by Maestro della Santa Cecilia (1290-1330) – maternal

image

Madonna and Child by Pacino di Bonaguida (1320) – maternal image

Tree of Life by Pacino di Bonaguida (1310-1315) – Saint Clare, Patron Saint of Convent of

Monticelli, is at top with Moses, Saint Francis, and Saint John the Evangelist – elevated

status of female (Saint)

Madonna and Child, Saint Peter and Saint Paul (with Martyrdom of both Saint Catherine

and Saint Agatha below) (1360) by Maestro della Misericordia dell „Accademia – maternal

image/elevated status of females (including Saint Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Madonna with Child, Eight Saints, and Four Angels by Cenni di Francesco (1380-1385) –

maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Saint Agnes; Saint Domitilla by Andrea Bonaiuti (1365-1370) – elevated status of females

(Saints)

Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints by Niccolo‟ di Tommaso (1365-1370) –

maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Madonna and Child; Annunciation; Crucifixion and Saints by Jacopo di Cione (1380) –

maternal image

Madonna della Misericordia by Maestro della Misericordia dell „Accademia (1365-1370) –

nuns at feet, on knees praying around Madonna – angels hovering above her – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Same artist as above – Nativity (1370-1375) – maternal image

Same artist as above – Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (1380) – maternal image

Madonna and Child Enthroned between Saint John the Baptist and Bernard and Eight

Angels by Giotto di Stefano (1356+) – maternal image/elevated status of angels

(nongendered)

Coronation of the Virgin by Jacopodi Cione (lead artist), Niccolo di Tommaso, Simon di

Lapo (1372-1373) – maternal image

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

175

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Annunciation – Unknown Florentine Painter (date uncertain) – maternal image/traditional

female image

The Pentecost by Andrea di Cione detto (1365-1370) – Madonna in middle – Holy Spirit

appears as tongues of fire – maternal image

Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Andrew or Philip Nicholas, John the Baptist,

James the Lesser, by same artist as above (1355) – maternal image

Crucifixion, the Mourning Virgin, and John the Baptist, Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint

Francis by Bernardo Daddi (1335) – maternal image/elevated status of female (Saint)

Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (Catherine of Alexandria, John the Baptist,

Margaret, Bishop Saint); Crucifixion of Mourners and Mary Magdalene; The Meeting of

Three Living and Three Dead Men by Bernardo Daddi (1340) – maternal image/traditional

female image/elevated status of females (Saints)/nontraditional female image

Madonna Enthroned with Two Angels and Four Saints (John the Baptist, Zenobius, Michael

the Archangel, the Blessed Agnes of Assisi) and Coronation of the Virgin by Taddeo Gaddi

(1325-1330) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)/elevated status of

female (Saint)

Madonna and Child; Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter (above: The Annunciation

Angel; The Virgin Annunciate) by Taddeo Gaddi (1345-1350) – maternal image/elevated

status of angels (nongendered)

Coronation of the Virgin and Saints by Bernardo Daddi (1340-1345) – maternal image

The Madonna of Humility and Saints (Lawrence, Onofrius, James the Greater,

Bartholomew) by Pucciodi Simone (1350-1360) – maternal image

Crucifixion with Mourners and Mary Magdalene at the Foot of the Cross by Bernardo Daddi

(1343) – (stigmata blood of Christ from hands and right side flows into cups held by winged

angels) – traditional female image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Crucifixion with Mourners and Mary Magdalene at the Foot of the Cross; Saint Mary

Magdalene; Saint Michael the Archangel (later noted as Chief/Head of all Angels, not a

Saint, per se); Saint Julian; Saint Martha by Bernardo Daddi & Puccio di Simone (1340-

1345) – traditional female image/elevated status of females (Saints)

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

176

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Coronation of the Virgin and Saints (Julian, Margaret, Mary Magdalene, Romuald) by

Maestrodelle Immagini Domenicane (1340-1345) – maternal image/elevated status of

females (Saints)

Same artist as above – Madonna and Child with Saints (Benedict, Lucy, the Blesser

Gherardesea di Pisa, Bishop Saint) – (1340-1345) – maternal image/elevated status of

female (Saint)

FLOOR TWO:

Madonna della Passione – black representations with black Christ Child by Andreas Ritzos

(1450-1460) – maternal image

Massacre of the Innocents, Adoration of the Magi, Flight into Egypt by Bottega di Jacopo di

Cione (in massacre scene, women helpless – with hands in the air) – (1430) – traditional

female images

Madonna and Child by Maestro Della Preddella Dell‟Ashmolean (1360-1365) – maternal

image

Virgin of Humility by Jacopo Di Cione (1365-1370) – maternal image/traditional female

image

Virgin of Humility and an Angel by Don Silvestro Dei Gherarducci (1360-1365) – maternal

image/traditional female image/elevated status of angel (nongendered)

Madonna and Child between Saints John the Baptist and Nicholas, and Two Angels Holding

Curtain by “Francesco” (1391) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Enthroned Madonna and Child with Angels and Saints by Mariotto di Nardo (1391) –

maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Coronation of the Virgin, Angels, and Saints by Niccolo di Pietro Gerini (1401) – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Enthroned Madonna and Child with Two Angels and Saints by Niccolo di Pietro Gerini

(1404) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Coronation of the Virgin between Angels and Saints by Jacopo di Cambio (1336) – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

177

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Virgin of Humility between Two Angels and Saints Peter, John the Baptist, a Female Saint

(unnamed), and Saint Stephen by Piero di Giovanni detto Lorenzo Monaco (1420-1422) –

maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)/elevated status of female (Saint)

Annunciatory Angel, Crucifixion with Mourners and the Magdalene Virgin Annunciate,

Saints Paul, Pope Gregory, Dominic by Maestro Bella Predella Sherman (1425) – maternal

image/elevated status of angel (nongendered)

Virgin of Heavenly Humility between Saints Stephen and Reparata by Mariotto Di Nardo

(1395-1400) – maternal image/traditional female image

Coronation of the Virgin with Four Musical Angels and Saints Francis, John the Baptist, and

Dominic by Giovanni Di Marco detto Giovanni Dal Ponte (1425) – maternal image/elevated

status of angels (nongendered)

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine by Bicci Di Lorenzo (1423-1425) – Christ offers ring to

Saint Catherine – marriage rite recalled – “giving of the ring” most important moment in the

ritual – traditional AND nontraditional female image/elevated status of female (Saint

Catherine)

Stories of the Virgin – Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation at the Temple, Flight

into Egypt, Christ Among the Doctors, Death, Assumption by Mariotto Christofano (1455)

– maternal image

Madonna and Child with Two Angels by Andrea Di Giusto Manzini (1435) – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Enthroned Madonna and Child with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Francis, Zanobius, and

Mary Magdalene by Lippo D-Andrea – robin with red breast a reconfiguration of Christ‟s

sacrifice (Christ Child holds birth in left hand, blesses outwardly with right hand) (1430-

1440) – maternal image/elevated status of female (Saint)/nontraditional female image (Saint

Catherine)

Virgin of Humility by Giovanni di Francesco Toscani (1425) – maternal image/traditional

female image

Madonna and Child and Saints John the Baptist, Francis, Matthew, and Magdalene by

Rossello Di Jacopo Franchi (1400-1450) – maternal image/elevated status of female (Saint)

Madonna and Child and Saints Anthony Abbott and Peter, Julian, and John the Baptist by

Maestro Del (1416) – maternal image

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

178

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Saint Yves Administering Justice by Maestro Di Sant ivo (1405-1410) – Saint Yves of

Brittany, in jurist robes (an ecclesiastic judge), gives all attention and justice to the poor,

orphans, and widows. Ignoring the flattery of the rich, his commitment is to protecting the

rights of the weakest (anomic, because against the norm of the times) – traditional female

images

Annunciatory Angel and Saint Michael, Virgin Annunciate, and Saint Dorothy by Giovanni

Di Marco detto Giovanni Dal Ponte (1420-1430) – maternal image/traditional female

image/elevated status of angel (nongendered)/elevated status of female (Saint)

Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints by Rossello Di Jacopo Franchi (1420) –

maternal image/traditional female image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Madonna and Child with Saints Antony Abbott, John the Baptist, Lawrence, and Peter by

Scolaio Di Giovanni (1420) – maternal image

Saint Catherine of Alexandria by Maestro Della Madonna Straus (1400-1410) – again, with

plume in right hand – elevated status of female (Saint)/nontraditional female image (Saint

Catherine)

Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist, Saint Nicholas, and Angels by Gherardo Di

Jacopo detto Starina (1400-1410) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Annunciation by Maestro Della Madonna Straus (1395-1400) – Angel Gabriel announcing

to Mary that she will bear a son, to be called Jesus, as a virgin – maternal image/elevated

status of angel (nongendered)

Man of Sorrows between the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Symbols of the Passion

by Piero Di Giovanni detto Lorenzo Monaco (1404) – maternal image

Annunciation and Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Antony Abbott, Proculus, and Francis of

Assisi by Piero Di Giovanni detto Lorenzo Monaco (1410-1415) – maternal image/elevated

status of female (Saint Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Same artist as above – Madonna and Child with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Margaret,

John the Baptist, and Peter (1408) – maternal image/elevated status of females (Saints –

including Saint Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Enthroned Madonna and Child with Angels and Saints by Piero Di Giovanni detto Lorenzo

Monaco (a Camaldolite Monk) (1410) – (NOTE: Madonna larger than saints or angels) –

maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities http://www.ijrssh.com

(IJRSSH) 2017, Vol. No. 7, Issue No. IV, Oct-Dec e-ISSN: 2249-4642, p-ISSN: 2454-4671

179

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES

Same artist as above – Virgin in Sorrow – (1405-1410) – maternal image/traditional female

image

Same artist as above – Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1388-1390) – book in left hand (often

seen with plume to write and/or book) – elevated status of female (Saint

Catherine)/nontraditional female image

Virgin of Humility and Six Angels by Agnolo Gaddi (1385-1390) – maternal

image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist (cusp on Saint Stephen) by

Spinello Di Luca detto Spinello Aretino (1400-1405) – maternal image

Enthroned Madonna and Child and Four Angels by Spinello Di Luca detto Spinello Aretino

(1391) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Virgin of Heavenly Humility between Four Angels and Saints by Tommaso Del Mazza

(1370-1375) – maternal image/elevated status of angels (nongendered)

Enthroned Madonna and Child among Angels and Saints by Niccolo Di Pietro Gerini e

Lorenzo Di Niccolo Di Martino (1395-1400) – maternal image/elevated status of angels

(nongendered)

Trinity with Saints Francis and Mary Magdalene by Niccolo Di Pietro Gerini (1380-1385) –

threads from blood out mean “receiving the stigmata,” which Saint Francis does here –

traditional female image/elevated status of female (Saint)

Nativity of Christ and Announcement to the Shepherds by Cenni Di Francesco Di Ser Cenni

(1395) – maternal image

APPENDIX B

Cases Applied to Categories (overlap is common; hence numbers far exceed the 121 total cases):

Traditional Female Image = 32

Maternal Image = 89

Elevated Status of Angel(s) (nongendered) = 33

Elevated Status of Female(s) (Saints, with very few exceptions) = 32

Nontraditional Female Image = 16