Wisdom of Tradition in Modern Mosques in Bangladesh

-

Upload

syma-haque-trisha -

Category

Documents

-

view

95 -

download

0

Transcript of Wisdom of Tradition in Modern Mosques in Bangladesh

Wisdom of Tradition in Modern Mosques in Bangladesh.

Syma Haque Trisha

Lecturer, Department of Architecture, Bangladesh University of

Engineering and Technology.

Email: symahaque@gmail

.com

Bushra Nayeem Lecturer,

Department of Architecture,

Stamford University

Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Email: bushra_nayeem_11

@yahoo.com

Zarrin Tasnim

Architect, J.A.Architects.

Email: [email protected]

om

Abstract

Vision of modernist and traditional builder is bifurcated between holistic perception approach and meticulous focused view, Where Modernist artists moderate every aspect of art works from perspective view, traditional artist view things in depth and focused into particular spaces. The paper investigates existence of similar affiliation in case of mosque architecture of Bangladesh. The study would sequentially try to disclose the texture, decoration, materials and architectural vocabulary of Pre Mughal, Mughal, British colonial and contemporary Mosques of Bangladesh. Based on findings the paper discovers that in spite of proceedings towards modernity, traditional wisdom is still present in contemporary mosque architecture.

Keywords: Mosque architecture, Bengal, Contemporary Bangladesh,

Modernity, Traditional wisdom.

1. Preamble: The rapid modernization evident in the world we live in today has led many people fail to notice the relevance of the tradition. Modernism has shaped development pattern of buildings since the beginning of the 20th century. In the context of Bengal, Mosque Architecture is influenced by texture of material, ornamentation and surface decoration through the evolution of period. From the plain surface avoiding adornment to the utmost decorative surface is applied in mosque architecture flourished in different land by different inhabitants, rulers in different period. However this progression is related with the neighboring circumstance and human wits. However, now a day’s people are often caught up in the present moment and tend to focus only on the latest innovation and newest advancement, the past is easily overlooked. But at the same time while the majority of today’s built form is founded upon modernist philosophies and focus only on the most futuristic of design ideas, the traditional approach still remains. The Muslim architecture that developed in Bengal, had an individuality of its own, and it bears a definite stamps of this deltaic land. Islamic architecture of Bengal has shown mastering like other provincial uniqueness in effective use of available materials in adornment. Thus it is important to look at the evolution and the process of design which include the built form, natural environment and the socio cultural framework. The objective of understanding the historic process and the current design practices attempts to put light on this matter that after thousands of years, the traditional style remains very prominent in our modern mosque architecture and is anything but obsolete. A literature review was conducted on some selected Pre-Mughal, Mughal, British colonial period and contemporary Mosques of Dhaka. This study concentrates on the texture, decoration and materials of the mosques established during the discussed period in Dhaka. In selecting the mosque the authors selected almost all the relevant mosque in Dhaka having precious and research worthy ornamentation, surface decoration and materials. Several field visits have been conducted by the authors to examine the surface grain and decorations as well as the materials. A good number of photographs of the mosques of Dhaka have been taken by the authors for the study. Some of these have been presented in this paper. Some secondary sources e.g. interview of experts, books, journal articles, encyclopedias; photographs have been consulted for this study. Having done that an inference of the analysis will be talked about.

2. Notion of Tradition in mosque architecture of Bengal Traditional architecture mostly means architectural intend that is general to a place. These buildings might not form part of the highly modernized buildings of the same time and might implement simpler technologies in their construction. Modern Architecture is a kind of architecture that has led to the simplification of appearance. It also incorporates the practice of the idea and organization of a building to form highly attractive structures. Solemn use of the familiar symbolic forms of a particular culture of a particular people in a particular place denotes Traditional architecture. Mosque architecture has been introduced into Indian subcontinent at the very beginning of 13th century. Structural idea, materials and its

functionality played a vital role in that era and beyond. Besides these, integrated process of standard materials, skilled labor, innovative idea and socio-economic as well as geographical factors played an important part for contemporary mosque architecture. (Figure 1) shows a graphical representation of evolution of Mosque architecture of Bengal which forms a notion of tradition of mosque architecture of Bengal. At present ongoing modernization makes ground for change. In contemporary time, the architects because of being educated in modern style are now taking attempts to the holistic approach, minimalism, dramatic light and shadow, perspective view etc. The traditional ornamentation and texture in spaces are still present in spite of focusing on the overall idea and concept and simplicity of forms.

3. Indian subcontinent (12th-16th Century) The mosque, unlike the temple, is stern and simple, but it did not reject adornment. Ornamental Muslim art is inclined to colour and line or flat surface carving, and took the form of conventional ingenious geometric patterning (Marshall 1928). But Indo-Muslim architecture is deeply obliged to the remarkable affluence of ornamental art in Indian subcontinent. Thus indigenous flowers and foliage are apparent in the decoration of the buildings, raised by the Muslims in India (Codrington 1949). It is a hybrid artifact of the interaction of two cultures. (Figure 2)

Figure 1: Mosque architecture of Bengal. (Source: Hossain, M 2014)

Figure 2: Lattan Masjid, Gaur, Late 15th century, the right side is the vestibule. The curved eaves are the result of the influence of Bengal folk houses. (Source: http://www.kamit.jp/25_dictionary/xgau_1eng.htm)

3.1. From the Carving of Hindu motifs to the robustness of form:

Kutb-ul-Islam scripts the commencement of Islamic architecture in India (Codrington, 1943). This formative phase of mosque architecture in India began with the random utilization of temple spoils

(Burton-Page 1961). Qutb Minar, Iletmish’s tomb, Aria din ka jhopra resembles the feature of alternate angular and rounded flutes, endless variety of detail, in delicate sharpness of finish and laborious accuracy of workmanship, all of which are due to the Hindu masons. But because of the urgent need for economy and to the general revulsion of feeling against the excesses of the Khalji regime lavish display of ornament and richness of detail in Tughlaq buildings developed as a severe and

puritanical simplicity (Marshall 1928). The example of Tughlaq robust

and stern mosque buildings are Khirki Mosque & Adina Masjid at Hazrat Pandua (Hasan, S.M.1970).

Figure 3: Colonade around Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, Qutb complex. New Delhi, India Source: https://commons. wikimedia. org/wiki/File: Qutb_minar_from_Quwwat_ul-Islam_mosque,_Qutb_complex.jpg

Figure 4: Khirki Mosque Source: http:// kafila.org /2009/09/17/ the-khirki-and-the-begumpur- mosques/

4. Tradition of brick and terracotta architecture of Persia in Bengal: Early Islamic/Pre Mughal Period (later half of 13th -16th century A.D.) Bengal architecture, reminiscent of brick and terra-cotta building art was a continuation of the process of brick and terracotta architecture of Persia, which went through Bengal (Hasan 1979). Stone is an important constructional and decorative medium though frequently it appears as ashlar over a skeleton of the traditional brickwork (Wilber 1936). Example: Adina Mosque at Hazrat Pandua, Chhoto Sona Mosque at Gaud. Bengali masons, artists, and craftsmen indulged in the various forms of ornamental art like terra-cotta or carved brick ornamentation which was borrowed both from extraneous and indigenous sources; glazed or encaustic tile decorations; delicate stone carvings; and calligraphy. Terra-cotta or carved brick ornamentation was applied to adorn and protect the bare walls of the monuments as illustrated by the tympana of the Adina Masjid at Hazrat Pandua, the Tantipara, the Darasbari, both at Gaud, and the Bagha Mosque at Rajshahi.

4.1. Influence of structural elements in texture:

Various structural elements owed from Muslims also enriched Bengal mosque with texture. The transition from square base to the circle of the dome is attained by either squinch arch or pendentive (Hasan 1979). Example: Adina Mosque (stalactite pendentive) & Lattan mosque (squinch) at Gaud.

4.2. Influence of local masons, artists, and craftsmen in ornamentation:

Muslim terra-cotta art is delicately carved with floral and geometrical patterns with sharp chisel. The lotus, bell and chain, leaves and foliages are Hindu in origin. The employment of arabesque and calligraphy in the finest monuments of Gaud and Hazrat Pandua are Islamic in character. Muslim terra-cotta art was the indication of the mutual exchange of artistic ideas between two countries Indian and Persian work of local craftsmen because of their closely connected in race, language, and religion (Havell 1927). The panel decoration reflected the Bengali villager’s structural feature like the close-set paneling, plaited grass huts. (Wadia 1938). (Figure 5, 6, 7)

Figure 5: Mihrab Figure 6: Chain & bell motif (Adina Mosque)

Figure 7: Glazed brick (Lattan Mosque)

4.3. Use of the technique of polychrome tile (chinni tikri)

The technique of using polychrome tile in the mosque of pre-Mughal Bengal is Persian (Khan 1963). The most significant mosque of significant decorative style in pre-Mughal Bengal is certainly the Lattan Masjid (Figure 7) (Creighton 1817). They are very elegant and harmonious with well-balanced ornament and well-toned colouring. Glazed tiles were also skillfully used to adorn the bare walls of the Saith Gumbad Mosque and the Tomb of Khan Jahan Ali at Bagerhat (Smith n. d.)

4.4. Dani (art of stone carving) in ornamentation

The art of stone carving has been derived from the hieratic art, traces of which still survive in the pre-Muslim sites in Bengal (Dani 1961). The interlocking design and the frieze with Arabic lettering, the shallow decorative merlons above the central mihrab, the shallow carvings of the bell and hanging chain in the niche of the central mihrab, the geometrical designs and inscriptions in the mihrabs of the zenana gallery of the Adina Masjid are works of local Muslim craftsmen.

4.5. Stone cutter’s art in Ornamentation:

During the Husain Shahi period the stone cutter’s art was thoroughly practiced and perfected, as walls of gates and mosques were adorned with stone. The Small Golden Mosque provides the last glance of

the stone cutter’s art in Bengal (Dani 1961). The entire composition is bordered within a frame decorated with scroll work of inferior workmanship (Hasan S.M. 1979)

4.6. Application of gilding

Another characteristic feature of ornamental art in pre-Mughal Bengal is the application of gilding to domes and other parts of the structure as exemplified by the Small Golden and the Great Golden mosques at Gaud. Speaking of Great Golden Mosque, Abid ‘Ali says : “The domes were actually gilded and so much of the surface was ornamented in the way that under the rays of the sun or moon it looked like a mosque bruit entirely of gold, hence the name Sona Masjid”(Abid n. d.)

4.7. Development of calligraphy

The religious prohibition of representational art stimulated the development of calligraphy of three types -Kufic, Naskh and Nastaliq. Another interesting form of calligraphy is Tughra or imperial signature or royal titles, prefixed to letters addressed to diplomats and other documents, in which the letters are knotted to assume a decorative shape. Calligraphy, played a striking role in the field of decorative art, formed a decorative feature in Muslim architecture” (Hasan, Z. n. d.) They are either historical or religious in nature, the latter including Qur'anic texts, traditions, moral teachings and passages of ethical nature. The language is Arabic and occasionally Persian in Pre-Mughal period. Example: the Qutb Minar at Delhi A. D. 1232 and the Adina Masjid at Hazrat Pandua A.D. 1374-84.

5. Mughal period Mosque architecture of pre-Mughal Bengal put forth a profound influence on the development of characteristic features of Mughal architecture as well as Hindu building art of 17th and 18th century Bengal. The Mughal followed the homogeneous style which was followed in the Sultani mosque (Hasan, P. 1984).

Figure 8: The lalbagh fort mosque

Source: http://workmall.com/wfb2001/bangladesh/bangladesh_history_pakistan_period_1947_71.html (downloaded August. 2015)

Bengal architecture, exclusively mosque, in ornamentation and structuring bricks are used as principal materials like Persian architecture. Brick thus lends Bengal architecture a style which is distinctive, with its piercing arches and finishes so different from those in stone. Though the Sultani Mosques of Bengal have unique exposition of surface decoration including stone-cut design, terracotta, color marble and pleasuring ornamentation but the Mughal mosques are simply ornamented by plaster in different style as rectangle and arched panels, flat, four-centered or multi-foiled arches ( Figure 8). Plastered wall are some of the typical features of Mughal architecture of Bengal (Hasan, P. 1984). Due to lack of easy availability of architectural material like stone within the short distance, the Mughal mosque continued to be dominated by brick masonry in its building art and the molded terracotta made out of the fine textured alluvial clay for purposes of surface decoration (Ahmed 1986). Brick thus lends Bengal architecture a style which is distinct, with its pointed arches and finishes so different from those in stone. Though plaster was widely used on the surface of the walls as well, but from the very beginning of the 15th century we find the use of glazed tiles in Bengal as well as at Dhaka. They are used in both in mono colour as well as in polychrome. Some of them bear floral decorations on them. The manner in which different glazed tiles play a definite part in the design proves that they were manufactured locally (Dani 1961). The system of plastered walls and the construction of the dome are followed subsequent structures of Dhaka. Chawk Masjid, Jinjira Palace, Hosni Dalan etc. are examples. Star Mosque of Armanitola (1st half of 19th century), Parulia Mosque of Narshindhi district, Bajra Shahi Mosque (1741- 44 A.D.) of Noakhli, Bara Jamalpur Mosque (c. mid 18th century) of Gaibandha etc. are living examples. Perfect geometric shapes had been applied in the mosques of Dhaka. The domes of Khan Muhammad Mirdha’s Mosque (Figure 10) have basal leaf, decorating in geometric forms like diamond, triangular shapes and are crowned tall finials in step by step. Considerable experimentations in three-dimensional application of geometry also took place in the transitional zone of the dome. The use of the traditional devices of squench and pendentives, as inherited from pre-Islamic architectural traditions, was continued and also elaborated upon by the Muslims. In decoration, complicated geometrical patterns, arabesque designs consisting of vegetal motifs, Arabic and Persian calligraphy are frequently used. The mihrab, quibla wall as well as facade are ornamented by the frequent use of plaster but terracotta and stucco use occasionally the motifs of the decoration are organized two-dimensional decorative patterns consisted not only abstract geometric shapes but also included vegetal designs. Lalbag Fort Mosque, Khan Muhammad Mirdha’s Mosque, Haji Khwaja Shahbaz Mosque’s (Figure 11) mihrabs are ornamented with smooth terracotta floral and geometric ornaments. Therefore, we can say that, Mughal mosques of Dhaka are the existing example of blending of the foreign elements in to the taste of local concept and tradition. ((Hasan, S.M. 1984)

Figure 9: exterior view of Sat Gumbad Mosque

Figure 10: Khan Muhammad Mridha’s Mosque

Figure 11: Shahbaz Khan Mosque

6. British colonial period

Mosque architecture in Bangladesh, after the decline of the Mughals, was exposed to this new influence. Mosques built within this period were mostly initiated and supported by locally influential people. The period did not generate any specific innovative design characteristics. A few, however, are significant for their extensive and elaborate ornamentation.

Figure 12: Arch detail of Star Mosque (Tara Masjid)( Source: Author)

Figure 13: Chinitikri ( Source: Author)

Figure 14: Qosba Mosque, Puran Dhaka ( Source: Author)

Figure 15: Qosba Mosque ( Source: Author)

One of the most ornate and attractive mosques of Dhaka built during the colonial period(the 19th century) is the Tara Masjid of Armanitola,Dhaka (Figure 12) by Mirza Golam Pir. In early 20th century, the surface was redecorated with Chinitikri work (Figure 13) (mosaic work of broken China porcelain pieces), a decorative style that was popular during the 1930s. Chinitikri tile work assumes another texture by using assorted pieces of different designs of glazed tiles on the interior surfaces of the mosque. (Figure 14, 15)This mosque is one of the few remaining architectural example of the Chinitikri (Chinese pieces) method of mosaic decoration. This ornamental practice is found in the striking star pattern that is in fact the cause for the mosque's current acclaim and popular name, Star Mosque or Sitara Masjid.

7. Contemporary period (1948 to present)

Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 led Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) into a new period of development. Utilitarian building actions have been seen during this time. Though the architectural and formal aspects of the mosques are not appealing, most are highly decorated with geometric and formal patterns and calligraphic inscriptions on their exterior facades. Baitus Sajud Jami Masjid is one such example. The mosque has several modern architectural features whilst at the same time it preserves the traditional principles of Mughal architecture.

Figure 16: Chandgaon Mosque-exterior

Figure 17: Chandgaon Mosque- Interior

Figure 18: Savar Memorial Mosque ( Source: Author)

Figure 19: Baitul Mukarram Mosque ( Source: Author)

Figure 20: Chondrima Uddan Mosque ( Source: Author)

Figure 21: Chondrima Uddan Mosque ( Source: Author)

Figure 22: Dhanmondi Lake mosque(Vitti)( Source: Author)

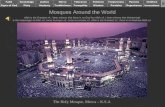

Baitul Mukarram’s (Figure 19) large cube shape by architect, T Abdul Hussain Thariani was modeled to that of the Ka’abah at Mecca. Excessive ornamentation is avoided throughout the mosque, since minimizing ornamentation is typical of modern architecture. Simultaneously some traditional features of Mughal Arched openings can be seen. Mahakhali Gausul Azam Mosque (Figure 24), Baitul Aman Jame Mosque (Figure 26) also put up with the same distinctiveness. At the present time, professional architects are more concerned with the concept of form and space and the scale of the structure, rather than surface ornamentation. Fragmented exterior surfaces designed with familiar elements are employed to bring the building down to human scale, instead of a monumental or overwhelming exterior treatment. Savar Memorial Mosque, Chondrima Uddan Mosque (Figure 20, 21) in Dhaka District is a good example of such practices.

Another structure, Purto Bhaban Mosque in Dhaka explores the plastic nature of concrete and plays with clarity of space and quality of light and shade as well. Other examples may be found where architects abandon the well-established norm of dome and minaret. Damra Factory Mosque near Dhaka and the mosque at the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute at Gazipur show such avoidance of traditional approaches.

Figure 23: Mahakhali Gausul Azam Mosque interior ( Source: Author)

Figure 24: Mahakhali Gausul Azam Mosque exterior ( Source: Author)

Figure 25: Cantonment Central Mosque ( Source: Author)

Figure 26: Baitul Aman Jame Mosque, Barisal ( Source: Author)

This mosque on the suburban periphery of the port of Chittagong in Bangladesh seeks to fulfil the traditional role of a mosque as both a place of spirituality and as a gathering place for the community. The Chandgaon mosque (Figure 16, 17) makes a definitive architectural statement in a different direction, pointing to the contemporary, to a desire to live in spaces that reflect the universal values of the present day. In spite of that when we go closure we can see some textured grains in the wall of the mosque which signifies the habitual intrinsic uniqueness. In Dhanmondi Lake mosque (by Vitti Sthapati Brindo) Calligraphy is transformed into a new textured language through screened façade (Figure 22). Some contemporary architects are exploring traditional architecture in terms of form, features, and the use of material and construction methods for designing mosques. The Rural Development Academy Central Mosque at Bogra and Bakshi Bazaar Mosque at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology in Dhaka are built with exposed bricks emphasizing indigenous material of this region. Different experiments with the archetype reveal various aspects through which architects are trying to explore the available resources and at the same time consider the traditional and fundamental concepts of mosque architecture avoiding excess ornamentation & encouraging texture through simple surface material with the play of light. M

8. Inference:

Figure 27: Evolution of ornamentation and texture of mosque architecture Again in modern eras architecture is going back to simplicity avoiding

excessive ornamentation & decoration. In precedent mosque architecture,

texture is found most of the time in individual elements rather than overall

formal expression in perspective. At recent times only the media of texture

has changed emphasizing more on space quality & environmental issues. In

a nutshell, texture & diversity is an indigenous nature of Bengal .Only the

modes of texture changes from Past to Present, sometimes to achieve

power, dignity, sometimes to avoid luxury & to gain economic assurance.

Human wants to see variety sometimes in plain simplicity & sometimes in

vigorous pattern of texture. Continuing modernization makes ground for

transformation in architecture. However, in spite of focusing on the overall

Traditional Influence

Overseas Influence

Hindu Motifs

Robustness of forms

Local Brick and Terracotta architecture

Persian Brick and Terracotta architecture

Hindu Terracotta art from Bengal

Persian Muslim Art

Persian Technique of chinnitikri

Local stone carvings, application of gildings

Calligraphy

Continuation of influence of brick architecture of Persia

Local use of Glazed Tiles

Local influence

No specific Design Charecteristics

Traditional Influence

Less surface ornamentation, Modernization

Pre

Mu

ghal

Mo

squ

e

Mu

ghal

Mo

squ

e

Co

nte

mp

ora

ry

Mo

squ

e

Bri

tish

Co

lon

ial

Pe

rio

d

Pa

st f

orm

ing

th

e t

rad

itio

n

Pre

sen

t

idea and concept and simplicity of forms the traditional ornamentation and

texture is not compromised. The gesture of trying to affirm the present by

breaking with the past brings into play the presence of the past. Traditional

wisdom does necessarily entail play with precedent and historical

continuity; however, they have increased the possibilities for artistic

expression. Indeed they are practically obvious. Traditional wisdom

proceeds with a distinction.

Reference Abid Ali Khan. n. d. Memoirs of Gaur and Pandua, edited by H. Stapleton, Calcutta. Ahmed, Nazimuddin.1986. Architectural Legacies of the British Period. In Buildings of the British Raj in Bangladesh, edited by J. Sandy, 22-68. Dhaka: University Press. Burton-Page, J. 1961. Dihli, in El, vol. I, NS Codrington, K. de B. 1943. Akbar Master Builder. in IAL, vol. XVII, NS, No. 1 Codrington, K. de B. 1949. The Place o f Archaeology in Indian Studies, Inaugural Lecture, delivered on Oct. 28th, 1948, Institute of Archaeology Creighton, M. 1817. The Ruins of Gaur, London; Orme, R. Gawre: Description o f its Ruins with four inscriptions taken in the Arabic copy, IOL Dani, Ahmed Hasan. 1961.Muslim Architecture in Bengal. Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Pakistan Hasan, Parween. 1984. Sultanate Mosque Types in Bangladesh: Origins and Development. Ph.D. diss., Harvard University Hasan, S.M. 1970. Adina Masjid at Hazrat Pandua Hasan, Syed Mahmudul. 1979. Mosque Architecture of Pre-Mughal Bengal. Dhaka: University Press Hasan, Z. n. d. Muslim Calligraphy, IAL, N.S. vol. IX, No. I & 2 Havell, E.B. 1927.Indian Architecture, London Khan, F.A.1963. Banbhore, Department o f Archaeology, Government of Pakistan Marshall, J. 1928.The Monuments o f Muslim Indian, in CHI, vol. Ill, Cambridge Smith, V.A. n. d. A History of Fine Arts in India and Ceylon, Third edition, Khandalavala, Bombay Stubbs-Wisner, B. 1933. Persian Brick and tile Architecture, in Art and Archaeology, vol. XXXIV, Jan-Dee Wadia, D.N. 1938. Geology of India, Calcutta Wilber, D.B. 1936. The Religious Edifice and Community life, in Muslim World, vol. XXVI, No.3 Hasan, S.M. 1979, Mosque Architecture of Pre-Mughal Bengal

Shamsuzzoha, A.T.M. January 2011, Structure, Decoration and Materials: Mughal Mosques of Medieval Dhaka, 93 94 Journal of the Bangladesh Association of Young Researchers (JBAYR), Volume 1, Number 1, January 2011, Page 93-107 ISSN 1991-0746 (Print), ISSN 2220-119X (Online), DOI:10.3329/jbayr.v1i1.6841

Source: Hossain, M, Islamic learning and research center B.Arch. Thesis, 2014