Winter 2003 (PDF)

Transcript of Winter 2003 (PDF)

R E S E A R C H N E W S • ‘ M U S C L E M A N ’ • C A M P A I G N C O U N T D O W N

Undergraduate education at CBS is undergoing a

profound transformation, driven by scientific

advances, growing interest and career opportunities,

the U’s molecular and cellular biology initiative, and

national trends in biology education. Page 9

Undergraduate education at CBS is undergoing a

profound transformation, driven by scientific

advances, growing interest and career opportunities,

the U’s molecular and cellular biology initiative, and

national trends in biology education. Page 9

R E S E A R C H N E W S • ‘ M U S C L E M A N ’ • C A M P A I G N C O U N T D O W N

MetamorphosisMetamorphosis

As part of a large, public research university, the College of Biological

Sciences’ primary role is to advance the boundaries of knowledge and

train the next generation of scientists. But there’s another—perhaps

equally important—role that supports that goal: training biology

teachers for Minnesota’s and the nation’s secondary schools.

These teachers are vital to our success because they inspire and pre-pare middle and high school students to pursue science careers. Thefact that our students, most of whom are from Minnesota schools, con-

tinue to be more qualified every year is a tribute to these dedicated individuals on the front lineof science education.

Aspiring to be a science teacher at a secondary school may not seem like a lofty goal. Butmany alumni have found teaching a very stimulating and rewarding career. And as the amountof scientific knowledge continues to expand, it becomes more challenging as well.

Kalli Binkowski (B.S. ’95), profiled on page 15, had planned to pursue a career in geneticsresearch. But after teaching an undergraduate class while working on her Ph.D., she becamehooked on teaching. Now a teacher at the Spring Lake Park high school she once attended,she is very satisfied with her decision. “Having the chance to light a spark in a young person’smind is very gratifying,” she says.

We want teachers like Kalli to know how much we appreciate their efforts. This fall we askedour freshmen to nominate high school science teachers who played a key role in their deci-sion to major in biology. And at our annual Recognition and Appreciation Dinner, we honoredthose who earned the most praise.

Earlier this year, CBS received a $1.7 million grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Instituteto provide training for science teachers. I’m proud of this grant because it enables us to do morefor teachers like Kalli and for young people who may one day cross our threshold. Even better,our own Itasca Biological Station will be the primary campus. The site was chosen because it iscentral to schools in greater Minnesota, where there is a shortage of science teachers.

The program adds an important new dimension to CBS undergraduate education. As the meta-morphosis of our undergraduate education continues, we will add other courses that allow stu-dents to learn by discovery and experience. This reflects an emerging national trend to move biol-ogy education from a fact-based discipline to one that focuses on concepts and learning by doing.

I hope you enjoy this issue of BIO. As always, your comments and suggestions are welcome.

Robert Elde, DeanCollege of Biological Sciences [email protected]

On the front line of science education

C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

FROM THE DEAN

Address correspondence to:e-mail: [email protected]

Visit our Web site at www.cbs.umn.edu.

Robert Elde, dean

WINTER 2003 ■ Vol. 2 No. 1

DEANRobert Elde

EDITORPeggy Rinard

ADVISERSJanene ConnellyDirector of Development and External Relations

Judd SheridanAssociate Dean

John AndersonAssociate Dean

Department HeadsDavid BernlohrBiochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics

Robert SternerEcology, Evolution, and Behavior

Kate VandenBoschPlant Biology

Brian Van NessGenetics, Cell Biology, andDevelopment

CONTRIBUTORSLija GreenseidEmily JohnstonJustin Piehowski

GRAPHIC DESIGNShawn Welch U of M Printing Services

PRINTINGU of M Printing Services

IN THIS ISSUE

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 1

COVER STORY

FEATURES

IN EVERY ISSUE

9 Metamorphosis Undergraduate education at CBS is undergoing a profound transfor-mation driven by scientific advances, growing interest and careeropportunities, the U’s molecular and cellular biology initiative, andnational trends in biology education.

2 AbstractsFungi family tree, lion kings, rainforest biodiversity, plant genomics, biodegradation…

4 College NewsCargill building nears completion, donors and scholars recognized, U Legislative Request, CBS People…

16 Alumni NewsVolunteer opportunities, networking events, Class Notes…

18 Calendar of EventsCheck out the line-up of winter events.

6 FIELD NOTES — Monarchs bring citizen scientists out of cocoons.

7 BIOCHEMISTRY — ‘Muscle man’ pumps iron in the lab.

13 STUDENT LIFE — Biology House makes the U smaller & friendlier.

14 CAMPAIGN COUNTDOWN — Carol and Wayne Pletcher Fellowship.

15 ALUMNI PROFILE — Alumna trades lab for classroom.

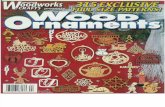

On the Cover Undergraduates Joline Lushine and Erek Lam work with researcher Karen Oberhauser in herlaboratory. Providing undergraduates with more research opportunities like this one is a key goal of thetransformation in progress at CBS. See story page 9. Oberhauser, who is nationally known for her monarchresearch and outreach programs, is profiled in a separate story on page 6. Photo by Richard Anderson

PPAA

GGEE

77

‘Muscle man’ Dave Thomas

The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, veteran status, or sexual orientation.

Printed on elementally chlorine-free recycled paper containing 20 percent post-consumer waste.

PPAA

GGEE

99

Undergraduate education

PPAA

GGEE

11

55

Science teacher Kalli Binkowski

BIO is published three times a year by theUniversity of Minnesota College of BiologicalSciences for alumni, faculty, staff, and friendsof the College. It is available in alternative for-mats upon request; please call 612-624-0774or fax 612-624-2785.

We’ve called them scum, lifesavers, andeven hors d’oeuvres, but only since 1995has anyone called them relatives. That

was the year scientists determined thatmushrooms, yeast, mildews, and otherfungi are more closely related to animalsthan to plants. Now, the NationalScience Foundation has awarded $2.65million to the University of Minnesota —

along with Duke, Oregon State, and Clarkuniversities — to sort out relationshipsamong this diverse group of organisms.The four-year grant is part of NSF’sAssembling the Tree of Life program.David McLaughlin, professor of plantbiology, is principal investigator for theuniversity’s $510,000 share of the grant.

Several widely used drugs, includingpenicillin, are made from fungi. The studycould point researchers to species offungi that may produce new drugs orother useful products. Fungi perform avery useful role in the environment, help-ing to form soil, recycle leaves and wood,and enable trees to absorb nutrientsmore efficiently. McLaughlin says the evolutionary line leading to fungi splitfrom lines leading to plants and animalsmore than 1.5 billion years ago. Only 5-10percent of an estimated 1.5 millionspecies are known. ■

Cynthia Weinig, new faculty member inthe Department of Plant Biology, has

received a Young Investigator Awardfrom the National Science Foundation’sPlant Genomics Research Project(PGRP) for $1.7 million over five years.

Weinig uses Arabidopsis to study thegenetic basis of adaptation. She and

collaborator Julin Maloof at UC Davis,who will share the award, are interest-

ed in understanding how selection actson crowding responses in agricultural

settings. More specifically, plants canmodify their phenotype (for instanceshape or form) in response to crowdingand the onset of competition for sunlight.There is now strong evidence that flexibledevelopmental responses to crowding,such as stem elongation, confer a fitness

advantage to individual plants in natural

settings. However, little is known aboutthe genetic basis of adaptive evolutionaryresponses. Characterizing the loci target-ed by natural and artificial selection is aprimary aim of their research.

Weinig, who arrived at CBS this fall,earned a Ph.D. in evolutionary biologyfrom Indiana University and served a post-doctoral fellowship at Brown University. ■

2 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

George Weiblen, plant biology, helpedprove there are roughly 25 million fewerbug species on the earth than previouslybelieved. His findings, published in Nature,were based on associations betweeninsects and plant families. Now he has wona $625,000 Packard Fellowship to continuestudying biodiversity in tropical rainforests.

Weiblen gathers ecological and geneticdata to study the evolution of species intropical rainforests, using fig trees andinsects that interact with them as a modelsystem for testing theories of co-evolution.He combines natural history with molecu-lar techniques in his research.

The highly competitive Packard Fellowshipallows the nation’s most promising youngscientists and engineers to pursueresearch with few restrictions. ClaudiaSchmidt-Dannert, BMBB, received aPackard Fellowship last year. ■

George Weiblen studiesbiodiversity in a CostaRican rainforest.

Hygrocybe conica, photographed by DavidMcLaughlin at Cedar Creek. See the UM fungicollection at www.fungi.umn.edu.

Fewer bugs, more money NSF taps CBS professor to chart fungal family tree

Cynthia Weinig wins NSF Young Investigator Award

DAV

ID M

CLA

UG

HLI

N

Cynthia Weinig with Arabidopsis seedlings ingrowth chamber.

JUST

IN P

IEH

OW

SKI

Larry Wackett, head of BMBB’s division ofmicrobial biochemistry, recently receivedtwo grants. The first, $224,000 from theDepartment of Energy, will enable him toidentify microbial genes with novel bio-chemical reactions. While genomes of sev-eral hundred microorganisms have beensequenced, the function of many genesremains unknown.

The second grant, $200,000 from the U.S.Department of Agriculture, supportsresearch on the bacterial breakdown of s-triazine compounds such as the herbicide

atrazine. Previous research has revealedthe metabolic pathways and the evolution-ary steps that allow bacteria to degradeatrazine in soil and water. Wackett and hiscolleagues will also look at the regulationof the atrazine genes in PseudomonasADP, a bacterium they isolated from anabandoned agricultural chemical dealer-ship in Little Falls, Minnesota.

Wackett, who is also a member of theBiotechnology Institute, has published 10papers so far this year. Researchers in hisgroup, which focuses on biodegradation

and biocatalysis, study underlying mecha-nisms by which bacteria transform chemi-cals in their environment. This workhelps scientists understand hownature recycles compounds andhow microbial metabolism canbe harnessed to generatecommercial chemicalsvia environmen-tally-friendlyprocesses. ■

Male lions with long, dark manes suffermore from the African heat, but whenrival males threaten or females arechecking out potential suitors, they arethe coolest cats in the jungle, accordingto a study by PeytonWest, graduate stu-dent in theDepartment ofEcology, Evolution,and Behavior, andadviser CraigPacker,DistinguishedMcKnight UniversityProfessor.

When West andPacker examinedthe data on several dozen males thathad been sedated and had blood sam-ples drawn, they found a strong correla-tion between blood testosterone levelsand mane color.

“Dark color tends to be found in high-testosterone males. So it isn’t surprisingthat females would prefer darker manesand males would be intimidated by

males with darker manes,” West said.Packer added that “the lion’s mane func-tions much like the peacock’s tail; it’s avisual cue indicating a male’s health andfitness.”

West’s study was covered by media out-lets around the world, including the StarTribune, New York Times, WashingtonPost, San Francisco Chronicle, LondonTelegraph, Independent Online (SouthAfrica), National Geographic, MPR, NPR,The BBC, WPVI (Philadelphia), WFAA(Dallas), BAYN(Tampa), KSWB (SanDiego), and CNN. ■

John Ward, plant biology, and collabora-tors at the University of Maryland andBaylor College of Medicine, will receive$2.8 million over four years for their role inArabidopsis 2010. The goal of the effort,funded by the National ScienceFoundation, is to learn the function of allArabidopsis genes by the year 2010.Arabidopsis is the primary model organ-ism used in plant genomics. The researchwill provide insights into how to make cropplants more productive and more resistantto pests and climate variations.

The group’s project, “Arabidopsis 2010:Discovering transporters for essential min-erals and toxic ions in plants,” will focuson understanding the functions of 57genes that are homologous to cationantiporters—membrane proteins thatexport cations such as sodium and calciumfrom plant cells. Several of the genes areknown to have important roles in resist-ance to salt stress, which is an importantand growing concern for agriculture, andfor cellular calcium homeostasis.

Ward is also working on a bioinformaticsproject to characterize all Arabidopsis mem-brane proteins on a genome-wide scale. ■

Dark manes attract female lions and the media Arabidopsis 2010

Microbial biochemistry and biodegradation

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 3

PEY

TON

WES

T

High school science teachers honored

CBS donors meet scholarship andfellowship recipients

New faculty boostresearch enterprise

4

Hiring new faculty with the combinedresources of the Molecular and CellularBiology Initiative and reallocation has had atransforming impact on the research enter-prise, as evidenced by a dramatic surge innew grants awarded to faculty in the coredepartments. In the Department of PlantBiology, 10 new faculty hired in the past twoyears have obtained 12 grants (from NSF,USDA, DOE, NIH, and the PackardFoundation). In the Department ofBiochemistry, Molecular Biology, andBiophysics (BMBB), eight faculty hired inthe past three years have been awarded 11multi-year national grants (AHA, NIH, NSF).And in the Department of Genetics, CellBiology, and Development, nine new facultyhave brought in 11 grants from national andlocal sources. ■

John Stangl, who teaches biology atNorth St. Paul High School, wasamong five teachers honored at theRecognition and Appreciation Dinner.Honorees were selected from amongmore than 100 high school science teachers nominated byfreshmen for their inspirationand guidance. Freshman MattKuehl said Stangl taughtstudents that “Biology isnot just a class, but is partof us, and emphasized the

importance and brilliance of nature…”and that he “put every ounce of hisenergy and soul into his AP biologyclass.” Stangl also helped Kuehl get a full scholarship to the U. ■

C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

Donors who contribute to CBS

scholarships and fellowships met

the grateful recipients of their

generosity at the annual CBS

Recognition and Appreciation

Dinner, held October 10 in the

McNamara Alumni Center. Dean

Elde spoke on investing in the next

generation and introduced this

year’s scholarship and fellowship

recipients. Elde and Professor Pete

Snustad, plant biology, presented

an Outstanding Achievement Award

to Julie Kirihara (B.S.’81 and Ph.D.

’88 Biochemistry). Kirihara, founder

of ATG laboratories and president of

MNBIO, received the award for sci-

entific contributions and her efforts

to promote Minnesota’s biotech

industry. If you would like informa-

tion on establishing or con-

tributing to a CBS scholar-

ship or fellowship fund, or

making a gift to the

College, contact

Janene Connelly at

connelly@biosci.

cbs.umn.edu. ■

Construction of the Cargill Building for Microbialand Plant Genomics is nearing completion. Thebuilding, funded by a $10 million gift from Cargill,Inc. and a matching grant from the state, will behome to more than 22 principal investigators and175 supporting researchers. Research will focuson using microorganisms to clean up the envi-ronment; making agricultural plants more resist-ant to disease, pests, and climate; and devel-oping new drugs for cancer and other life-threat-ening diseases. An opening celebration isplanned for spring, 2003.

Cargill Building for Microbial and Plant Genomics

Julie Kirihara received theOutstanding AchievementAward from Dean Elde andProfessor Snustad.

John Stangl, biology teacher atNorth St. Paul High School,with student Matt Kuehl.

Victor Bloomfield, BMBB andDean of the Graduate School, estab-lished a graduate fellowship in molecular biophysics with a $50,000inheritance from his mother that was matched by the 21st CenturyGraduate Fellowship Endowment.Ben Mueller, a student in theM.D./Ph.D. program, is the firstrecipient of the fellowship. The twowere featured on the cover of the fallissue of Legacy, the University ofMinnesota Foundation’s magazine.

Irv Liener, professor emeritus ofbiochemistry, was awarded the2002 Sterling B. Hendricks lectureship.The Hendricks lectureship recognizes senior scientists in industry, university,or government positions who have made important contributions to thechemical science of agriculture. Liener received a B.S. degree in food tech-nology from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1941 and a Ph.D. in biochemistry and nutrition from the University of Southern California in 1949.In1949 he joined the Department of Biochemistry at the U of M, where hetaught and did research on soybeans until his retirement in 1985.

Henrietta Miller, retired BMBB administrator, with a newly installedplaque in the Henrietta Miller Garden,located in front of Gortner Laboratories.The garden was dedicated to Henriettaon her retirement in 1983, after morethan 40 years of dedicated service to thedepartment. Henrietta and her husband,Phil, have remained very involved withthe CBS community.

Herbert Jonas, professor emeritus of botany, passed away on September13 at the age of 87. After emigrating from Germany in 1934, Jonas didresearch for the U.S. government and the University of Virginia before becoming a professor of pharmacognosy at the University of Minnesota. In1968, he moved to the Department of Botany, where he remained until 1985.His interests included mineral nutrition and chemotaxonomy.

The Lake Itasca Biological Station received $50,000 from the estate ofThomas Morley. Morley received his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoraldegrees in botany from the University of California, Berkeley during the1940s. He joined the faculty of the University of Minnesota in 1949. Morleywas widely recognized as an expert on Minnesota native flora and a chartermember of the Nature Conservancy. He was also very active in the MinnesotaNative Plant society.

The University is asking the 2003 MinnesotaLegislature for $96 million for the 2004-05Biennium. The budget breaks down into four categories:

■ $26 million for implementing academicdirections

■ $88 million for supporting talented facultyand staff

■ $20 million for helping students realize educational goals

■ $58 million to build and maintain academicinfrastructure

The U will contribute $96 million through reallo-cation and tuition increases. Unlike in previousyears, no programs or projects are specifiedbecause lawmakers will need to address thebudget deficit before awarding new funds. ■

For the second year in a row, the University ofMinnesota – Twin Cities was ranked thirdamong public research universities in thenation. The study, conducted by the Universityof Florida, is based on quantitative measuresof performance rather than opinion and repu-tation, which are used in other well-knownrankings. Only the University of Michigan andthe University of California, Berkeley scoredhigher than the U. The report can be viewedat http://thecenter.ufl.edu. ■

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 5

PEOPLE

‘U’ third amongresearch universities

U Legislative Request

A colorful new display and hands-on activities attractedlots of visitors to CBS’ booth at the State Fair this summer.Activities included a biology computer quiz, isolatingsalmon DNA, learning about the role of fermentation inbiocatalysis, and looking at a variety of microbes through amicroscope.

CBS at the State Fair

Monarch project brings citizen scientists

Cindy Petersen knows theperfect way to spend asummer day: walking a

transect through a big open field,counting milkweed plants, andsearching their surfaces for thepinhole-sized eggs and tiger-striped caterpillars thatannounce the presence ofmonarch butterflies.

Petersen, a Chanhassen middleschool teacher, is one of hun-dreds of volunteers across NorthAmerica who gather data for theMonarch Larva Monitoring

Project (MLMP), a citizen scienceeffort directed by ecology, evolu-tion, and behavior assistant pro-fessor Karen Oberhauser. Theproject is providing scientistswith valuable insights into theecology of what is likelyAmerica’s most charismatic—andenigmatic—butterfly.

Monarchs are unusual amonginsects in that, rather than goingdormant in winter, they go south.Western monarchs migrate toCalifornia. Those east of theRockies fly a thousand miles ormore to mountainside forests incentral Mexico, where they hud-dle together, covering the treeslike orange, antennaed shingles.In spring they head north again,taking two generations to reachthe furthest part of their range.

The MLMP, begun by Oberhauserand EEB grad student MichellePrysby in 1997, is an attempt toimprove understanding of themigration and correspondingpopulation fluctuations.Volunteers select sites wheremilkweed, monarch caterpillars’sole food source, abounds. Theyscout their sites weekly duringbreeding season, recording thenumber of eggs and larvae ofvarious stages they find on themilkweed plants. They send theirtallies to Oberhauser’s lab, wherethey are combined and analyzed.

This past year scientists wereparticularly interested in theMLMP observers’ reports. A freakfrost had killed millions of mon-

archs in the Mexican mountains,and everyone wondered what theimpact would be on summerpopulations.

“Monarch numbers were lowerthan average, but not the lowestwe’ve seen during the six yearsof the project,” Oberhauser says.“Monarch population dynamicsare driven by events that occurduring the winter, the spring andfall migrations, and the summerbreeding period. The MLMP willhelp to understand how all ofthese interact.”

The MLMP also benefits partici-pants by giving them a taste ofthe scientific method and achance to observe the intricaciesof nature. “They’re learning aboutecological interactions occurringin ecosystems close to theirhomes,” Oberhauser says.“They’re really seeing how com-plex and wonderful nature is.”

The MLMP is an offshoot of aneducational program calledMonarchs in the Classroom thatOberhauser initiated more than adecade ago as a way to teachchildren about insect biology andscientific methodology.

“Monarchs are a perfect organ-ism to use in classrooms,”Oberhauser says. “They’re easyto rear in captivity, and they’renot scary.”

For more information on MLMP,check out www.mlmp.org.

—Mary K. Hoff

out of their cocoons

6 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

“They’re learning

about ecological

interactions occur-

ring in ecosystems

close to their

homes. They’re

really seeing how

complex and won-

derful nature is.”

—Karen Oberhauser

Karen Oberhauser is well known in classrooms and fields throughoutMinnesota and the U.S. for her outreach programs on monarch butterflies.She was recently featured in the New York Times.

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

An ex-wrestler who triedout for the 1972 Olympicteam, David Thomas has

built a career as a different type ofmuscle man. He has long beenfascinated by the motions of largeproteins found in assemblies, andwhen he turned to muscle pro-teins, he was hooked. Now a pro-fessor of biochemistry, molecularbiology, and biophysics, Thomas isunlocking secrets of muscle pro-teins that hold the keys to muscu-lar dystrophy, some forms of heartdisease, and other maladies.

Getting hooked is more than ametaphor when the subject ismyosin, the muscle protein thatdoes most of the work of contrac-tion. When the signal to contractarrives in a muscle cell, myosinmolecules hook onto strands of aneighboring protein called actin.They pull the whole assemblytighter, then let go, grab actinagain, and tug in a repeated ratch-eting motion. Individual cycles lastless than a thousandth of a second,yet are too slow for the standardtechniques of magnetic resonanceand laser spectroscopy to catch.

“This is kind of a blind spot formost physical techniques, but itseems to be the most importanttime frame for all kinds of molec-ular machines,” Thomas says.Such machines include the tinymotors that move chemicalsacross membranes, transportmaterials within cells, and powerthe whip-like flagellum that pro-pels a sperm cell.

More than two decades ago,Thomas modified a magnetic reso-

nance technique to “tag” myosinso its motions could be followed.In 1982 he overturned then-cur-rent theory when he found thatduring contraction, myosin spendsonly 20 percent of its time doingactual work. The “recoverystroke”—when myosin is inbetween tugs—eats up 80 percentof the time. Also, it has long beenknown that energy for muscle con-traction usually comes from thesplitting of a small, energy-richmolecule called ATP. Thomas dis-covered that the energy releasedfrom ATP is used to pry myosinaway from actin. That is, ATPdrives the recovery stroke, not theactual work.

Sharing the excitement of discov-ery, Thomas has welcomed a longlist of undergraduates into his lab.Among the first was ChristineWendt, a CBS student who wenton to Medical School at theUniversity and is now a pulmonaryspecialist in the department ofmedicine. A current CBS student,

Erika Helgerson, has received ascholarship from the LilleheiFoundation and is working withOsha Roopnorine, an assistantprofessor in Thomas’ researchgroup, on mutations in myosin thatcause thickening of heart muscle(cardiomyopathy), the leadingcause of sudden death in youngathletes.

Lately, Thomas and colleagueLaDora Thompson of the MedicalSchool have found a molecularexplanation for muscle aging:Myosin changes its structure sothat during contraction, it spendseven less time doing actual workwhile consuming the sameamount of energy as youngermuscle.

Still active physically, Thomasmaintains several more muscle-related projects. Thanks to him,CBS is doing some heavy lifting inthe fight against debilitating condi-tions that strike people of all ages.

—Deane Morrison

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 7

Sharing the

excitement of

discovery,

Thomas has

welcomed a

long list of

undergraduates

into his lab.

‘Muscle man’ Dave Thomaspumps iron in the lab

Professor Dave Thomas, a former collegiate wrestler, studies muscle proteinsassociated with muscular dystrophy, heart disease, and related disorders.Undergraduates Andrew Jensen and Erika Helgerson work in his lab.

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

8 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

Undergraduate Jolene Lushineassists with research in the lab-oratory of Karen Oberhauser,who studies monarch butterflies.Creating more research oppor-tunities for undergraduates is akey part of the transformation.

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

f you were an undergraduate studentat CBS more than a few years ago, youmight be surprised to drop in on a

class today and see how much haschanged.

Since you’ve been gone, several forceshave converged to reshape the undergrad-uate experience: the U’s reorganization ofthe biological sciences and molecular andcellular biology initiative, the continuingexplosion of knowledge in biology, a grow-ing interest in biology and career opportu-nities for biologists, and national trends inbiology education.

So, if you did come back to the U today,you might be sitting in a classroom in anew $80 million building, learning some-thing that hadn’t been discovered whenyou were an undergrad, getting moreopportunities for hands-on researchthan you had before, working with a newcrop of talented young faculty, living in aspecial residence hall for biology stu-dents, and feeling pretty optimistic aboutyour future.

But the metamorphosis isn’t complete.Robin Wright, new associate dean forfaculty and academic affairs, who arrivedjust after the first of the year, is planninga College-wide effort to take CBS to thenext level. Her goal will be to capitalizeon all the positive changes that are tak-ing place and make CBS one of the topplaces in the U.S. to get an undergradu-ate biology degree.

How it all beganChange had been brewing at CBS for along time, but in retrospect, two eventsmark the beginning of a new era: theadmission of freshmen to the college in1997 and the reorganization of the biologi-cal sciences in 1998.

Freshman admission was an importantstep because CBS and students alike canaccomplish a lot more when they arecommitted to a four-year relationship.Students have more course and researchopportunities, a better chance to get toknow each other and faculty, the feeling of

being part of a community, and more aca-demic and career guidance than they didin the past.

The biological sciences reorganizationunified similar basic sciences depart-ments that had evolved separately on theMinneapolis and St. Paul campuses tosupport health sciences and agriculture.The result was fewer but much strongerdepartments poised to seize opportunitiesgenerated by the revolution in the biologi-cal sciences. The molecular and cellularbiology initiative took the reorganization a step further, by allocating state andUniversity funds to hire 41 new faculty andbuild a home – the $80 million Molecularand Cellular Biology Building – for threeof the consolidated departments.

Each of the new departments took overresponsibility for education, which focusedand strengthened undergraduate pro-grams and increased the number of facul-ty who taught undergraduate classes.Faculty in the Medical School, who hadpreviously taught only medical students,

Undergraduate education at CBS is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by scientificadvances, growing interest and career opportunities, the U’s molecular and cellular biology initiative,and national trends in biology education.

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 9

I

10 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

began teaching courses for undergradu-ates.

“There’s a deeper understanding of theimportance of quality undergraduate edu-cation now than there was before thereorganization, says Robert Elde, dean ofthe College of Biological Sciences, who,along with Medical School Dean AlfredMichael, spearheaded the effort.

When he became dean seven years ago,Elde adopted the philosophy that if youput students first, everything else will fallinto place almost naturally. The approachis espoused by Stanford President DonaldKennedy in his book Academic Duty. Overthe past few years CBS has added numer-ous programs that put students first,including Freshman Seminars taught bydistinguished faculty; Biology House, aspecial residence for CBS students;BioBuds, which matches freshmen withupper class students; the Alumni MentorProgram; and the CBS Career Center.This summer CBS will launch a three-dayorientation camp for all freshmen atItasca Biological Station and Laboratories.

Growing interest in biologyInterest in biology, driven by the sequenc-ing of the human genome and other high-ly publicized achievements, has growndramatically. Over the past five years, thesize of the entering freshman class hasincreased from 113 to 351. The caliber ofstudents is also increasing. Half of thestudents in this year’s freshman classwere in the top 10 percent of their highschool class. And a record number ofprospective University students arerequesting information from theAdmissions Office about majoring in biol-ogy. In fact, biology is now among the topfive majors in which students express aninterest, along with pre-med, engineer-ing, communications, and psychology.

At the same time, biologists at thenational level are rethinking the way biol-ogy is taught. This is driven in part by thegrowing volume of knowledge and in partby concerns that curriculum tends to bebased on memorizing facts rather thanunderstanding concepts. Last year, anissue of Science was devoted to revamp-ing undergraduate science curriculum tomake it both more conceptual and morehands-on.

From facts to concepts andimagesA curriculum that is experiential andbased on discovery is a much more effec-tive way to learn, says Elde. “We arestruggling as biologists with how to breakthrough the mountain of facts and distillto concepts and in some cases images,as with the mountain of data produced bygenomics.”

John Anderson, interim associate deanfor faculty and academic affairs, adds thatareas of biology need to be taught togeth-er. “We need to integrate topics so wedon’t talk about biochemistry, cell biolo-gy, and genetics in isolation,” he says.“We need to weave them togetherbecause they are all interrelated. And weneed to be more cognizant of whole-world implications.”

This summer CBS piloted a new program for 30 freshmen at Itasca Biological Station. The purpose was tohelp students get acquainted with each other, faculty, and the curriculum before starting school. The pro-gram will be extended to all freshmen next year.

SAR

AH

HU

HTA

John Anderson

Franklin Barnwell

John Beatty

David Bernlohr

David Biesboer

Iris Charvat

William Cunningham

Margaret Davis

Richard Hanson

Alan Hooper

Norman Kerr

Willard Koukkari

P.T. Magee

Robert McKinnell

Richard Phillips

Douglas Pratt

Palmer Rogers

Murray Rosenberg

Leslie Schiff

Janet Schottel

D. Peter Snustad

Thomas Soulen

Anthony Starfield

David Thomas

Susan Wick

Amy Winkel

Clare Woodward

Val Woodward

Robert Zink

AWARD WINNERSCBS faculty who have been recognizedby the University for distinguishedteaching since 1990.*

* For a complete list of teaching awardwinners, visit http://www.cbs.umn.edu/1ab_cbs/1eii_teachwinners.html

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 11

Anderson teaches a Freshman Seminarcalled “Six Billion and Who’s Counting?”which focuses on consequences of globalpopulation growth from an ecosystemperspective.

“When is the system going to crash?Even students interested in molecularissues need to be aware of globalissues,” he says.

Teaching is being rewarded “Undergraduate biology education is defi-nitely on the radar screen around thecountry,” says Robin Wright, new associ-ate dean for faculty and academic affairs,who just arrived from the University ofWashington. “There have been bigchanges lately. It used to be that teachingdidn’t make a difference to a biologist’sresearch career, but that’s no longer thecase.”

Over the past five years, Wright says, theNational Science Foundation has beenchanging the way it reviews grants toreflect this trend. While funding decisionsused to be made based on research meritalone, the NSF and other funding agen-cies now want to know what else they’llget for their money besides research,Wright says.

“Even if the research plan is excellent,the grant may not be funded if theresearcher doesn’t include a plan forimpact of the research on teaching andoutreach,” she adds. “This is a dramaticchange that affects all researchersbecause everyone needs to get grants inorder to carry out their research.”

Another trend Wright sees is the additionof math courses to the curriculum.Historically, biology has been a descrip-tive rather than quantitative science, but

today’s undergraduatesneed more math to handlelarge amounts of data pro-duced by genomics as well as modelingecosystem processes. Adding courses to help students strengthen their writingskills is also a national trend, as is integrating technology into learning.

Yet another sign that the topic is hot, theNational Academy of Sciences recentlypublished a book called BIO 2010:Transforming Undergraduate Educationfor Future Research Biologists.

Still room for improvementWith all the changes at CBS over the pastfew years, there is still room for improve-ment. Some of the most immediateneeds are revamping the core curricu-lum, getting faculty more involved inmentoring students, and making it easier

Although undergraduate education atCBS is new and improved with more

good things to come, CBS has alwaysbeen known for its outstanding under-graduate teachers.

One of them is John Anderson, profes-sor of biochemistry and interim dean forfaculty and academic affairs. Anderson,who has taught undergraduate educa-tion on and off during his 35 years withthe College, has garnered every distinc-tion the College and University give torecognize excellence in teaching, as wellas a ”Nobel Prize for Excellence inTeaching” given to him by his studentsin 2002.

What’s his secret?“It’s understanding where the student ison their educational journey so that Ican meet them where they are and take

them from there,” he says. “Periodically,I introduce a little humor, which is par-ticularly effective if it’s self deprecating.That gets the message across that I’mjust an ordinary person who happens tobe familiar with the material. I’mapproachable and I won’t take offense ifthey don’t get it. I also set high expecta-tions and make it clear what thoseexpectations are.”

One recent example of Anderson meeting students where they are is his Web-based course in biochemistry,which was the College’s first Web-basedclass. When he learned of the need forsuch a course, he readily agreed toadapt his for that audience. And he isnow meeting students from all over the United States and beyond via theInternet to bring them along on theireducational journeys.

John Anderson has received many awards for distinguishedteaching. He is shown here with students in his FreshmanSeminar, called “Six Billion and Who’s Counting?” whichaddresses the impact of population growth on the Earth’secosystems.

A HISTORY OF EXCELLENCE IN TEACHING

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

for students to becomeinvolved in research labs.

The CBS core curriculum haslong been an issue, says Janet Schottel,chair of the Educational Policy Committeeand Director of Undergraduate Studies for the Department of Biochemistry,Molecular Biology, and Biophysics. CBSused to have a core curriculum for allmajors, but over the years it has evolvedto allow more specialization withinmajors. While students now have moreflexibility, some faculty are concerned thattheir education may not be as broad-based, Schottel says. One solution underconsideration is a consolidation of severalpreviously required core courses into atwo-semester sequence that all studentswould be required to take.

Schottel says she and other faculty arelooking forward to discussing the planwith Wright.

Another improvement in progress isinvolving more faculty as mentors anddelineating the roles and responsibilitiesof faculty mentors and advisers in theStudent Services Office.

As per a new plan, Student Services advisers will be responsible for guidingfirst-year students, and faculty mentorswill take over after students declare amajor. Faculty mentors will be assigned to students based on majors or areas ofinterest. Advisers will still do some of thepaperwork, but faculty mentors will get toknow students and help them plan theirfutures.

Providing opportunities to work inresearch labs has always been a strengthat CBS, but with freshman admission andgrowing enrollments, the need for studentresearch opportunities, particularly forfreshmen and sophomores, is increasing.Many faculty are reluctant to take onyounger students because they don’t havethe time to train them. To address this, anew course in laboratory techniques isbeing planned, Schottel says. The two-

level course will teach lab safety, tech-niques, the scientific process, and how todevelop a research project.

What lies aheadFiguring out how CBS undergraduate pro-grams need to change to better serve stu-dents and reflect national trends isWright’s top priority. As the College’s newassociate dean for academic and facultyaffairs, she will be responsible for workingwith departments, faculty, staff, and stu-dents to shape undergraduate educationprograms.

It’s an assignment that she is passionateabout, saying that her goal is to make CBSthe best place in the United States toteach and learn biology.

“When the NationalAcademy, the CarnegieFoundation, researchsocieties, and fundingagencies discuss excel-lence in biology educa-tion, I want theUniversity of Minnesotato be at the top of theirlist,” she says.

Wright adds that col-leges like CBS are rarein the U.S. because bio-logical sciences are typ-ically fragmented overmultiple departmentshoused in a college ofarts and sciences. Butthe unified structurecreated by the U’s reorganization uniquelypositions Minnesota to move into a nation-al leadership role in undergraduate biolo-gy education.

As she works with the CBS community tobuild a vision, some of her priorities willinclude:

■ Building inquiry and discovery into thecurriculum so students will think likebiologists rather than just thinking aboutbiology

■ Strengthening quantitative and computa-tional skills to prepare students forgenomics and other emerging areas

■ Integrating biology curriculum withother sciences and the liberal arts, sostudents will have a better idea of howbiology fits into the big picture

■ Increasing diversity and building a com-munity that celebrates the success ofindividuals

■ Encouraging faculty and teaching assis-tants to approach teaching with thesame rigor and creativity as they doresearch

“I accepted the position because I believeCBS has the potential to be a nationalleader, and because I want to help the College realize that potential,” she says.

“I couldn’t be more pleased that Robin hasjoined us,” Dean Elde says. “The searchcommittee did a great job of identifyingexcellent candidates around the countryand of getting Robin to come to Minnesotato help us achieve our goals.”

—Peggy Rinard

12 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

Jen Sandmeyer, who grew up in St. James, Minnesota, graduated fromCBS last spring. She is now a student at Harvard Medical School. Morethan half of this year’s freshman class graduated in the top 10 percentof their high school class.

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

There are few things asintimidating as freshmanyear at the University of

Minnesota. Especially if you areone of more than 700 freshmenassigned to Frontier Hall—the U’slargest residence. But if you are abiology major, there is hope.

It’s called Biology House— twocorridors of massive Frontier Hallwhere 60 biology students cur-rently live in suite-style rooms.CBS set up Biology House in 1997to create an environment wherefreshman biology majors couldget to know each other morequickly. It also makes studygroups easy to organize and verypopular.

Each year, a community adviser(C.A.) lives with and supervisesstudents in Biology House. Thisyear’s C.A. is Liz Bentzler, a jun-ior in CBS. Liz is responsible forhelping students with academic,personal, and social issues aswell as larger University andcommunity issues. She also han-dles emergencies and enforcesUniversity and hall regulations.

Liz became a C.A. because sheremembers all the questions shehad as a freshman. “I wanted toanswer all those questions andhelp first-year students getadjusted,” she says.

Liz is assisted by two ‘U Crew’students—Ashley Lawson andMelissa Goetter, who also live inBiology House. Ashley andMelissa, both sophomores, lived

in Biology House last year asfreshmen.

“We help our residents withclasses and issues that arise forfreshmen. More importantly, wehope to be friends,” Lawsonsaid.

New friendships are essential foradjusting to University life.Amanda Munzenmeyer, aBiology House freshman study-ing genetics, cell biology, anddevelopment, says makingfriends comes easily at BiologyHouse,

“There is always someonearound you can study with orwalk with to class,” she said.

Alumni also connect with stu-dents through Biology House. InDecember, the board of theBiological Sciences AlumniSociety hosted a pizza party atthe residence.

Biology House emphasizes aca-demics as well as socializing.This year staff are sponsoring“Biopoly,” a contest where stu-dents turn in a test score of 75percent or higher—or two testswhere the second test shows sig-nificant improvement—to the ‘UCrew’ students. For each sub-mission, the student gets achance to win a gift certificate toplaces that are vital to freshmanlife; Subway, Chipotle, U of MBookstores, and so on.

And Biology House residentshave a chance to exercise theirbodies as well as their minds. All

students who live, or have lived,there are eligible to play for thehouse’s soccer team, appropri-ately named “The Bio-Hazard.”

With all these connections,Biology House makes theUniversity feel more like a mole-cule than an ecosystem.

“Being in a house like this, aspart of the College of BiologicalSciences, makes the University amuch smaller place,” Lawsonsaid.

—Justin Piehowski

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 13

With all these

connections,

Biology House

makes the

University feel

more like a

molecule than

an ecosystem.

Biology House makes the U asmaller, friendlier place

Students in biology house often take advantage of close quarters to formbiology study groups.

JUST

IN P

IEH

OW

SKI

Carol Pletcher knows how impor-tant support can be to women ingraduate school. During her years

at CBS in the late 1970s, she had two sonsyet managed to earn a fellowship from theAmerican Association of UniversityWomen (AAUW).

“This fellowship served as a bridge to mylast year, which was very, very wonderful,”she said. Now, Carol and her husband,Wayne, want to be sure other youngwomen have the same kind of support byoffering their own fellowship.

In particular, Carol wants the fellowship togo to a woman who is interested in help-ing and supporting other women, rather

than only competing forherself. “Of course, Iwould like her to be bril-liant and do great bio-chemistry and all that,too,” she added.

Remembering her owntwo pregnancies in gradschool, “it was clearly anadjustment for the facultyto have a pregnantwoman running around,”she recalled. “It adds awhole new dimension tobeing a student.”

Carol describes being agrad student and studyingwith John Gander andother colleagues as oneof the most exciting andhappiest times of her life.

Carol often jokes that sheused some of the moneyfrom the AAUW fellowshipto pay parking tickets. “Iwas known for creativeparking,” she said.

Besides excelling in creative parking,Carol and her husband know how to lever-age opportunities.

Because the Pletchers started the fellow-ship during Campaign Minnesota, theUniversity of Minnesota’s 21st CenturyGraduate Fellowship Endowment matchedevery dollar. Additionally, Carol andWayne’s employers, Cargill and 3Mrespectively, matched each dollar thePletchers contributed. After all thematching, the Pletcher Fellowship totals$50,000.

“What we discovered was that by leverag-ing, the Fellowship came together easily.We hope that others will see the same

opportunity to support the University thatwe saw,” stated Carol.

The Pletchers plan to create fellowships atother schools; however, the University of

Minnesota was the first because of the21st Century Graduate FellowshipEndowment. “Once the matching fundsfrom the University became available, itwas the obvious thing to do,” she said.

While Carol is the University of Minnesotaalumna, she said this fellowship is a fami-ly effort. She and her husband are pas-sionate about education.

“We believe in the power of education. Webelieve in the power it gives you personal-ly for your own well-being and your ownenjoyment of life. We believe in the powerof education and what it gives you in yourprofessional life, the ability to have excit-ing, interesting, and rewarding jobs. Webelieve in the power of education and whatit does for society. An educated society, inour mind, has a whole different set ofoptions than an uneducated society.”

The Pletcher fellowship will help pay forthe education of a female graduate stu-dent studying biological sciences for yearsto come, but hopefully not too many park-ing tickets.

—Justin Piehowski

14 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

C A M PA I G N MINNESOTA CAMPAIGN COUNTDOWNALUMNA USES MATCHING FUNDS TO CREATE A FELLOWSHIP TO SUPPORT A WOMAN GRADUATE STUDENT AT CBS

Carol and Wayne Pletcher at home with Queen Elizabeth, their poodle.

TIM

RU

MM

ELH

OFF

Carol wants the fellowship to

go to a woman who is inter-

ested in helping and sup-

porting other woman, rather

than competing with them.

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 15

Kalli Ann Binkowski wasone of those kids whoknow just what they

want to be when they grow up.As a sixth grader at KennethHall in Spring Lake Park, shedecided she would become ascientist and study genetics. Asa teen she began researchingplant cell regeneration in theCollege of Biological Sciencesthrough a mentoring programfor high school students. Aftercompleting her undergraduatedegree at the University ofWisconsin, she returned to theUniversity of Minnesota to earnher Ph.D. She spent her dayslooking for the gene responsiblefor a gangly mutant ofArabidopsis thaliana as a Ph.D.student under plant biology fac-ulty member Neil Olszewski.“We isolated the gene, and itwas very, very cool,” she says.

Then life changed dramatically.As part of the price one pays forgetting a Ph.D., Binkowski had toteach an undergraduate class.She found herself spending herspare time thinking, not aboutthe latest puzzle in the lab, butabout better ways to get coursecontent across to her students.

“That’s when it hit me,” shesays. “I realized that I likedteaching a lot more than I likedoing research.” After lots ofsoul-searching and introspec-tion, she decided to go into edu-cation. She finished her master’sin plant biological sciences, thenearned a teaching degree.

Binkowski is now in her sixthyear of teaching science atSpring Lake Park HighSchool—the same school sheattended as a budding scientista dozen years ago.

“It’s a tremendously challeng-ing and interesting career,”she says. Particularly gratify-ing is the chance to light aspark in young people’s minds.“The kids are growing andchanging and you get to influ-ence that,” she says.

The first few years of teachingwere “tremendously difficult”as she got the hang of manag-ing 35 kids in a classroom,planning lessons, and carryingout administrative duties,Binkowski says. She laughsthat one of the toughest thingswas learning to call her formerinstructors by their firstnames. “I spent the wholesummer practicing,” she says.

Though she has no regrets forher career shift, Binkowski saysteaching has one major onedown side: the lack of apprecia-tion educators receive.“Teaching is not looked up to asa really respectable position.People say you get the summeroff so it’s an easy job, or there’sno money in it, so you’re notworth it,” she says. “As teacherswe know better.”

Through it all, Binkowskiremains grateful for the solidfoundation she received in CBS.“It’s given me a good under-

standing of biological conceptsalong the way,” she says. “I cansee the big picture because I’veseen so much of the picture.”

—Mary K. Hoff

Alumna trades lab

Kalli Ann Binkowki, M.S. ’95, finds teachingscience a very satisfying career.

RIC

HA

RD

AN

DER

SON

for a middle school classroom

“That’s when it

hit me. I realized

that I liked

teaching a lot

more than I liked

doing research.”

—Kalli Ann

Binkowski

16 C O L L E G E O F B I O L O G I C A L S C I E N C E S

Career and Internship FairAlumni are invited to participate in theCareer and Internship Fair by volunteeringa few hours between 11 a.m and 3 p.m. onFebruary 28 to review resumes, provideinterview tips, offer job search strategies,answer questions about their career, andhelp students participate in mock inter-views. If you are interested in helping,please e-mail [email protected] or callEmily at (612) 624-4770. This is a wonder-ful opportunity to help students as theybegin to think about their life after college.

Alumni Lost & Found The University of Minnesota AlumniAssociation conducted a search for U of Mgraduates this summer that resulted infinding more than 52,000 missing alumni.More than 900 are graduates of the Collegeof Biological Sciences. If you were lost andhave been found, welcome back! We’re veryhappy to be reconnected with you, andwould love to hear from you. Please let usknow what you’ve been up to. E-mail [email protected] with an update.

EMIL

Y JO

HN

STO

N

So many ways to volunteer at CBS

Join us at Northern Vineyards WineryJoin the deans, alumni, faculty, and staff atNorthern Vineyards Winery in Stillwater fornetworking, tours, and tasting on January 30from 6-8 p.m. Guests will take a tour of thecellar and have a chance to taste five of thebest wines hosted by the winemaker, as wellas a delicious array of bread, cheese, fruits,spreads and chocolates. Cost is $20 per per-son. You can register by calling (612) 624-4770 or e-mailing [email protected] free to invite a friend or colleague tojoin with fellow alumni and taste some ofMinnesota’s finest wines.

Volunteer Events

Networking Events

W hether you want to help others,give back some of what youreceived at CBS, or connect

with other alumni, there is a place for youat the College of Biological Sciences. Justask Dan Liedl ’96, who volunteers for CBSbecause he wants to meet people of simi-lar interests, to learn about advances in hisfield, and because it’s the right thing to do.“I wish I had started sooner,” says Dan,who finds that volunteering gives his lifebalance. “Time is valuable, but giving a fewhours a month can make a difference insomeone’s life,” he adds. By volunteeringyour time and talents you, like Dan andother CBS volunteers, can help studentsand the College and enrich your own life.

There are many different ways you can vol-unteer your time. The Biological SciencesAlumni Society Board meets monthly tostrengthen the relationship among theCollege, alumni, students, and the com-munity. Board committees meet everyother month to plan activities and recruit

new members. The Mentor Programmatches undergraduate students withalumni who hold jobs related to a student’sfield of interest. The Career Network is agroup of individuals who talk with studentsabout career-related issues. Job shadow-ing allows CBS students to spend a dayat work with an individual who shares theircareer interests. The Career andInternship Fair is a chance for alumni tointeract with students and help them planfor a career. Alumni are asked to reviewresumes, talk with students aboutjob search strategies, and provide inter-view tips as well as answer questionsabout their own careers and assist in prac-tice interviews. The Speakers Bureauinvites alumni to campus to talk with stu-dents about life after graduation.Volunteers are also needed to help planand implement Homecoming festivitieseach fall. To learn more about theseopportunities, contact Emily Johnston(612-624-4770 or [email protected]).

Side by side with 13 other alumni volunteers, Rebecca Marrs-Eide ‘01, Steve Schulstrom ‘84, and MikeCoyle ‘72 review resumes at the 2002 CBS Career and Internship Fair held in the McNamara AlumniCenter. CBS alumni volunteered a total of 929 hours last year, which equals a cash contribution of$14,910 as determined by Independent Sector.

RRiicchhaarrdd FFoorrbbeess ((BB..SS..,, MM..SS..,, PPhh..DD..,, ZZoooollooggyy,,11996644)) passed away in July, 2002 at the ageof 65. Forbes joined the faculty of PortlandState University in 1964 and was professoremeritus at the time of his death. A popularteacher, he won several awards for out-standing teaching during his tenure. He wasalso widely published as a writer and pho-tographer for scientific and popular publi-cations. He wrote a regular column forUrban Naturalist, an Audubon Societynewsletter, and took photographs forMammals of North America, published bythe Smithsonian. Forbes was also an activevolunteer for Oregon naturalist groups andfor public schools. While at the U of M, hewas very active at Itasca Biological Station.He is survived by his wife, Orcilia; daughter,Eryn; son, Bryan, and a granddaughter.

AAllaann PPrriiccee ((PPhh..DD.. iinn BBiioocchheemmiissttrryy,, 11996688)) iscurrently the Associate Director forInvestigative Oversight at the Office ofResearch Integrity in Rockville, Maryland.

WWiilllliiaamm BBeerrgg ((PPhh..DD.. iinn EEccoollooggyy,, 11997711))retired from the Minnesota Department ofNatural Resources this summer after 30years of service.

TTiimmootthhyy VVoolllleerr ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioollooggyy,, 11998844)) is anExecutive Search Consultant forLarsonAllen Search, LLC in Minneapolis.

EErrnneesstt RReettzzeell ((PPhh..DD.. iinn MMiiccrroobbiioollooggyy,, 11998844))married Catherine Clark in May 2002. Theymet during a workshop organized byCatherine in North Carolina, where Erniewas involved as co-principal investigator ofan NSF grant in pine genomics. WhileCatherine completes her studies in NC forthe next 6-12 months, they have discoveredthe joys of 3.5-cent-per-minute phone cardsand discount airfares.

BBiillll DDiieekkmmaann ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioollooggyy,, 11998877)) is theManager for QC Validation at Protein DesignLabs, Inc. in Plymouth.

AAnnddrreeww HHuuddaakk ((BB..SS.. iinn EEccoollooggyy,, EEvvoolluuttiioonn,,aanndd BBeehhaavviioorr,, 11999900)) is a Research Foresterwith the U.S. Forest Service Rocky MountainResearch Station in Moscow, Idaho. He isworking on several projects relating to veg-etation ecology at the landscape level.

GGrreettcchheenn RRaaddllooffff ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioollooggyy,, 11999911)) justmoved to Cincinnati to work in cancerresearch at Cincinnati Children’s HospitalMedical Center. She worked in Stella Davieslab at the University of Minnesota. When

Davies and her husband were recruited byCincinnati Children’s Hospital, they askedGretchen to join them and run the lab. Itwas an opportunity she couldn’t turn down!However, she does plan to move back toMinnesota in a few years.

Hats Off to TToodddd LLeemmkkee ((BB..SS.. iinn GGeenneettiiccss &&CCeellll BBiioollooggyy,, 11999922)),, JJuulliiee KKiirriihhaarraa ((BB..SS.. aannddPPhh..DD.. iinn BBiioocchheemmiissttrryy,, 11998811 && 11998888)),, andBBeevveerrllyy SScchhoommbbuurrgg ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioocchheemmiissttrryy,,11996677)) for volunteering at the first AlumniSpeakers Bureau. They kicked off our“Exploring Careers in the Life Sciences”series on October 2, 2002.

CChhrriissttiinnee SScchhooeennbbaauueerr ((BB..SS.. iinn EEccoollooggyy,,EEvvoolluuttiioonn && BBeehhaavviioorr,, 11999944)) served as aPeace Corps Volunteer in Niger, West Africafor two years following graduation. Uponreturning to the U.S., she took a positionwith the Minnesota Department ofAgriculture for two years in their chemistrylab. Christine is presently employed at theMinnesota Department of Health as anEnvironmental Analyst.

AAiimmeeee ((AAnnddeerrssoonn)) LLaawwssoonn ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioollooggyy,,11999966)) recently married Steven J. Lawsonand moved from St. Paul to Oakdale, MN.Aimee met Steven at the University of SouthAlabama during their physician assistantgraduate program in 1999.

PPaamm SSkkiinnnneerr ((BB..SS.. iinn GGeenneettiiccss && CCeellllBBiioollooggyy,, 11999955 aanndd PPhh..DD.. iinn PPaatthhoobbiioollooggyy,,11999988)) accepted a position this fall as assis-tant professor in the VeterinaryPathoBiology Department at the University.

JJeennnneeaa DDooww ((BB..SS.. iinn BBiioollooggyy,, 11999999)) recentlyjoined Eli Lilly as Specialty Representativein Eli Lilly’s Neuroscience/Retail SalesDivision.

KKaatthheerriinnee HHiimmeess ((BB..SS.. iinn NNeeuurroosscciieennccee,,11999999)) married Mark Lescher (B.A. inPsychology, 1997) in 2001. Katherine andMark first met in Comstock Hall in fall1996 where she was an office assistant andworked at the front desk, and he was a resident assistant.

Have any news to share? We’d love to hearfrom you. Send your Class Notes to EmilyJohnston, [email protected]. Andplease be sure to let us know if you move.

B I O ❙ W I N T E R 2 0 0 3 17

Class Notes

Welcome, new board membersDan LiedlB.S. Genetics, Cell Biology, andDevelopment, 1996

Kelly HadsallB.S. Biology, 1996

Attention mentors! You and your student are invited to attendNetworking Necessities on February 4 at6:30 p.m. in the McNamara AlumniCenter. Students and Mentors will learnhelpful hints for networking and try outtheir skills with those in attendance.Alumni can build their network as well.Look for more details to arrive soon!

Mentors and students are invited to theMentor Program Appreciation Reception onApril 15, 2003 at 5:30 p.m. in the McNamaraAlumni Center. This is an opportunity formentor pairs to meet one last time beforethe program officially ends. It's also achance to meet with other mentor pairs andfind out about their experiences.

A night at the theatreHave you ever thought about reconnectingwith other College alumni for an evening onthe town? If so, we have a fun opportunityfor you. You are invited to see “I Love You,You’re Perfect, Now Change” at thePlymouth Playhouse on April 25 at 7 p.m.Guests will enjoy a light buffet before theshow. Cost is $25 per person. You can regis-ter today by calling (612) 624-4770 or e-mailing [email protected]. Please feelfree to extend this invitation to your family,friends, and co-workers. We hope that you’lljoin us at this fun CBS event.

123 Snyder Hall1475 Gortner AvenueSt. Paul, MN 55108

Nonprofit Org.U.S. Postage

PPAAIIDDMpls., MN.

Permit No. 155

CBS Calendar Cedar Creek 60th AnniversaryNearly 300 people made the trip to Cedar Creek Natural History Area on Saturday,September 21 to help celebrate the 60th anniversary. Speaking at the program,Dean Elde said he believes Cedar Creek’s biodiversity research plots are betterknown outside of Minnesota as a symbol of the U than Northrop Mall. DavidTilman, CCNHA director, noted that humans now dominate global ecosystems, adramatic change from 60 years ago. Consequently, the value of Cedar Creek forstudying the impact of humans in ecosystems has also increased. And DavidHamilton, Vice President for University Research, called Cedar Creek a “jewel inthe University’s crown.” Activities, which followed the program, included a researchupdate from Tilman, tour of Cedar Bog Lake, demonstration of radio-tracking star-ring Goldy Gopher, and nature crafts and games for children.

www.cedarcreek.umn.edu

CLA

REN

CE

LEH

MA

N

NNeettwwoorrkkiinngg NNeecceessssiittiieess Monday, February 3, 6:30 p.m.,McNamara Alumni Center. Alumni andstudents are invited to learn and prac-tice networking tips.

CCaarreeeerr aanndd IInntteerrnnsshhiipp FFaaiirrThursday, February 28, 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., McNamara Alumni Center.Alumni are needed to review resumes,provide interview tips, offer job searchstrategies, answer questions abouttheir careers, and participate in mockinterviews.

OOuuttssttaannddiinngg AAcchhiieevveemmeenntt AAwwaarrddPPrreesseennttaattiioonn aanndd LLeeccttuurree

Thursday, March 6, 4 p.m., Earle BrownCenter. Douglas DeMaster will receivean Outstanding Achievement Award fromthe University and give a lecture titled,“Impossible Problems, ImprobableSolutions: The Life of a Wildlife Biologistin a Federal Regulatory Agency.”

UUMMAAAA MMeennttoorr CCoonnnneeccttiioonn AApppprreecciiaattiioonnRReecceeppttiioonn

Tuesday, April 15, 6 p.m., McNamaraAlumni Center. For alumni and stu-dents involved in the CBS MentorProgram.

CCBBSS CCoommmmeenncceemmeennttSaturday, May 17, 7:30 p.m. NorthropAuditorium.

Contact Emily Johnston [email protected] or (612) 624-4770for more information about any of theabove events.

![Covenant Magazine - [Winter 2003]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/568c4e531a28ab4916a7792d/covenant-magazine-winter-2003.jpg)