Herodias the Wild Huntress in the Legend of the Middle Ages, pt 2

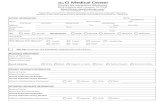

Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

-

Upload

31songofjoy -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

1/26

JSNT2SA (2006) 443-467 Copyright 2006 SAGE Publications

(London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) http://JSNT.sagepub.com

DOI: 10.1177/0142064X06065694

JaumaljortlvSmhattl**,

Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance (Mark 6.14-29)

Regina Janes

Department of English, Skidmore CollegeSaratoga Springs, NY 12866, [email protected]

Abstract

To some modern scholars' disapproval, Mark's and Matthew's John the Baptist

dies because of two women and a dance. Historically improbable, but theologically

essential, the episode in Mark makes theology through narrative structure, juxta

posing the Baptist's death with the raising of Jairus's daughter through the dance

of Herodias's daughter and paralleling Jairus's daughter's rising with Jesus' in

Mark's original ending, 16.8. While the two daughters point to resurrection and

Jesus' feeding the faithful, Herodias confirms John's identity as Elijah by acting

the murderous Jezebel to Herod's sympathetic Ahab. Matthew and Luke embrace

Mark's Elijanic identification ofthe Baptist but alter the Herod-Herodias story to

accommodate different theological interests. Erasing the Herodian family

altogether, John imitates Mark's structural placement ofthe Baptist as integral to

the promise of resurrection.

Key Words

John the Baptist, death of, Herodias, Mark 6.14-29, narrative structure.

Why does John the Baptist die because ofa dancing girl who demands hishead on a platter? Why is this story in the Gospels at all, and why is it told

only twice (by Mark and Matthew), rather than four times (by Matthew,

Mark, Luke and John)? The answerto thefirstquestion used to be 'history',

that is how the death of John happened, but scholars have become less

confident of the episode's historicity since at least the early twentieth

century. The Jesus Seminar represents one recent scholarly consensus

when it rates the daughter's dance merely 'possible', and her request for

an emplattered head 'improbable' (Tatum 1994: 13, 159-62). Yet if theepisode has been reduced from historical fact to scandalous rumor that

h f d i i M k l k i h

TJSTX

http://jsnt.sagepub.com/mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]://jsnt.sagepub.com/ -

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

2/26

444 Journal for the Study of the New Testament 28.4 (2006)

Mark included it or why others did not. The historically improbable, for

example, the resurrection of a dead body, is likely to be theologically

essential, for example, the resurrection of the body of Christ. The dance

(with the platter) clinches Mark's arguments about Jesus' identity and

resurrection and illuminates the Gospel's original ending at 16.8. A stone

that the builders persist in rejecting, the story of Herodlias's daughter is

the chipped cornerstone of the Gospel of Mark.

Recounting the prehistory of Jesus' resurrection, '[t]he beginning of the

good news ' (Mk 1.1, NRSV),Mark designs the death ofJohn both to double

Jesus' death and to contrast with two resurrections,Jesus' own and Jairus's

daughter'sa chiasmus: Jesus raises Jairus's daughter and John dies,

later Jesus dies and rises. The two women who kill John, bracketed by twowomen Jesus heals and three who attend his body, are produced in the

narrative by Mark's need to demonstrate John's identity as Elijah and to

reaffirm through John's death Jesus' resurrection and power to raise

others.

As Walter Wink argues in his classic study (1968), Mark's Baptist is

the secret Elijah to Jesus' secret Messiah. Jesus needs to be announced: it

is not enough for the Lord to come suddenly, to his temple, on his own.

Robert L. Webb remarks that without the Gospels' placement of Johnbefore Jesus, John wouldbe a 'minor character mentioned in Josephus... the

subject of a footnote or two in academic writing' (1991:19), but without

the Baptist there is either no one for Jesus to be or too many possible

identities. Without the prophetic tradition and the scriptures that define

God and Christ, Jesus would be no one at all! His life or death would

signify no more than that of some anonymous Celt or Scythian crucified

by Romans. Within that tradition, as Herod's interlocutors and Jesus'

disciples indicate, Jesus could be Elijah, John the Baptist, or one of the

prophets. If either Jesus or John is 'one of the prophets', his death at

authority'shands is neither new nor surprising. The scriptures, particularly

Jeremiah (Jer. 26.8-24; 11.18-23; 20.1-18; 38.4-6; also 1 Kgs 13.4; Josh.

13.22; Deut. 13.1-5), are littered with slaughtered, suffering prophets.

Identifying JolmasElijah,Marknarrowsthefieldandsimultaneouslyidenti-

fies Jesus as Lord. As the living John identifies Jesus as Christ, so a dying

Elijah enables a dying Messiah, concepts equally unknown to the pre-

Christian Jewish tradition(Wink 1968:14;Ohler 1999:461-76; Kazmierski

1996: 82).1

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

3/26

JANES Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance 445

A subject for paintings, sculpture and operas from the ninth to the

twentieth centuries, the story of the Baptist's death is a flashback inter

calated in the sending out of the apostles. Hearing of Jesus, whose 'name

had become known' (Mk 6.14), Herod identifies Jesus as John risen from

the dead. Arrested 'on account of Herodias, [Herod's] brother Philip's

wife', John had attacked Herod's and Herodias's marriage as unlawful.

Herodias wants John dead, but Herod 'liked to listen' to one he regarded

as 'righteous and holy'. At Herod's birthday fete, the daughter of Herodias

dances. Herod promises her whatever she wantsup to half his kingdom,

a formula from Esther. She asks her mother, who suggests the head of the

Baptist. The girl demands it, at once, on a platter; the king is sorry, but he

has made an oath. The executioner beheads John in the prison, brings thehead in charger, delivers it to the girl, and the girl gives it to her mother.2

'When his disciples heard about it, they came and took his body, and laid

it in a tomb' (Mk 6.29). From that tomb the Baptist does not rise.

The tale has not fared well with historical biblical scholars. Wink

collected sneers at this 'gory story', sleazy 'bazaar rumor', historically

improbable, legendary tissueof scandal woven around the Baptist's execu

tion (1968:10-11). Terence Donaldson (1999:36) and Nicole Wilkinson

Duran label the episode 'frankly lurid and gory.. .a brutal anecdote thatleads nowhere' (2002: 278). Some scholars find the story so repulsive

they skip over it altogether, as C.G. Montefiore did (1968:1,123). Jean

Delorme observes that Mk 6.17-29 'could easily be removed from its

context' (1998:116). Roger Aus calls it haggada that the author of Mark

found 'ready-made' and inserted to explain Herod's action, attaching 6.17-

29 to w . 14-16 (1988: 69). Duran cites, but does not endorse, Rudolf

Bultmann's assessment that the story is 'a legend exhibiting no Christian

characteristics' (2002:278). Duran's own powerful reading restores one

of Mark's intentions, glossed by a thousand years of painted 'Feasts of

Herod': Herod's court illustrates the hopeless corruption of the world

Jesus and John must leave, suffering violence (2002:278-84). For feminist

critics, notably Jennifer A. Glancy, gender displaces theology as scholarly

interetationreproducesthe misogynyofnineteenth-centuryartists (1994:

sufferings ofElijah'. The viewthat Elijah precedes the Messiah is now a common

Jewish belief, but lacks biblical warrant. Kazmierski contrasts the bizarre notion of the

rejected Elijah in Mk 9.13 with the common motifof the rejected prophet.2. Flaubert and Ren Girard make the head circulate on its platter at the banquet.

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

4/26

446 Journal for the Study of the New Testament 28.4 (2006)

43-47). Susan Lochrie Graham, resigned to 'traditional' accounts of a

seductive Salome, accepts the wicked women as 'foils' to the good women

elsewhere in Mark (1991: 151).

Theological readings do better with the elements of Mark's narrative,

from John's initial witness to hisfinalplatter: John's death parallels Jesus'

resurrection. Although he insists the episode 'is history', Philip Carrington

observes that Herod's feast is analogous to Passover, and the episode

introduces 'the thought of death and resurrection...openly for the first

time'(1960:126,131). For Edwin K.Broadhead, John precedes Jesus 'in

proclamation, in imprisonment, and now in execution... Jesus is seen in

the image ofJohn (6.14-16, 8.28)... John.. .provides the pattern for the

story of Jesus' (2001: 64). The earliest images of Herodias's dancingdaughter (ninth and tenth century) place on Herod's table bread and fish,

Christ's presence in John's head.3 In the fourteenth century John's head

became the host in the mass: both round, both offered for men's sins, both

served on a plate. Without the head on a platter, offered at a feast, the

parallel with the Last Supper breaks down. Still, there are other ways than

a dance to put John's head on a platter.

The lurid tale of the Baptist's murder is introduced by Herod's harping

on resurrection and identifying Jesus with John. From Simon Peter'smother to Jairus's daughter, Jesus has raised the sick and the dead; he has

cast out devils, calmed the seas and been rejected in his own country.

Now his twelve have been sent out to exorcise and to heal. At this

moment, with the word spreading through the twelve and the reader

waiting for their return, Herod too hears of Jesus working wonders, and he

remembers. He, or others around him, declare that 'John the baptizer has

been raisedfromthe dead; and for this reason, these powers are at work in

him' (Mk 6.14). Others offer alternative identificationsElijah, one of the

prophetsbut Herod, certain,repeats, 'John, whom I beheaded: he is risen'

(Mk 6.16, KJV; NRSV, 'has been raised'). Twice in thefirstthree verses of

a sixteen-verse episode Herod identifies Jesus as Johnrisenfromthe dead:

Mark seems to want us to notice.4 Is Jesus John raised from the dead? Is

3. The ninth-century evangelary at Chartres is reproduced in Dottin-Orsini (1996:

11); the tenth- (or eleventh-) century evangelary of Bamberg in Ewa Kuryluk (1987:

247).

4. Although few fail to notice that the story is aflashback,most literary readersfail to register what Herod says to introduce theflashback.Franoise Meltzer does

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

5/26

JANES Why the Daughter ojnHerodiasMustDance 447

Jesus the returned John? Who is Jesus? That questionwhich no one thinks

any longer to askMark is intent on making sure we never ask again.

Although Jairus's daughter has just been raised (Mk5.21-43), Herod'squestion directs attention to Jesus in John's death. Graham observes that

John'isdeliveredup', , while Jesus 'will be',

(Mk1.14,10.33; 1991: 152). John P. Meier notes the verbal parallels in

the burial accounts. The words used when John's disciples 'took his body,

and laid it in a tomb' (6.29) recur at Jesus' burial, 15.46:

(1980:399 n.). To J. Duncan M. Derret, the repeated ,

suggesting 'monument', is an unusual word for 'tomb' () (1985: II,

281). In its last verse, the oldest form of the Gospel contains the same

word for 'tomb' that closes on John: (16.8; 6.29).

As important as the tomb is the resurrection. At 6.14 Herod says that

John ('has been raised'). At 6.16, he shifts to (KJV, 'is

risen'; NRSV, 'has been raised'), rising to the same word that will be used

ofJesus' resurrection at 16.6. The young man in the tomb tells the women

Jesus 'is risen': (KJV; NRSV, 'has been raised'. The renaissance

editor who inserted these symmetrical numbers, 6.16,16.6, perhaps marked

something we have forgotten to see.) Winkclaims the verb for 'raised' that

Herod usesis different from the one used for Jesus' resurrection (1968: 10). Winkwas, however, misled by the Gospel's

alternation of the two verbs.

Although at Mk9.9-10, Wink's focus, the verb (,

) is used for the discussion between Jesus and the disciples

over rising from the dead, the Gospel regularlyuses both verbs, as in the

story of Jairus's daughter. Jesus uses the imperative, (KJV, 'arise';

NRSV, 'get up') to Jairus's daughter, who $ ('straightway

arose', KJV; NRSV, 'immediately.. .got up'; 5.41). Both verbs are used totell someone to rise and walk, for the sunrising,for children rising against

parents, and so on. After the death of the Baptist, both verbs are used at

once to 'raise and lift up' a single boy, who seemed dead after exorcism

(KJV, Mk9.27, ' , ; NRSV, Jesus 'lifted him up,

and he was able to stand'). Meier points out that Mark uses the noun

only in the dispute overresurrection with the Sadducees; other

wise he uses forms of the verbs and (2000:5). Although

'richer text': 'So far as I can determine, Mark's text is "richer" only because it

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

6/26

448 Journal for the Study of the New Testament28.4 (2006)

general discussions of resurrection as a topic use ,5

the Gospel

begins and ends with . When Jesus actually rises, the verb changes

backto the one Herod used of John.

AtHerod's feast, John's death is served indoors, in a prison, on a platter,

to 'courtiers and officers and.. .the leaders of Galilee'. He is buried by his

disciples, while Jesus' apostles returnto him. The next event is Jesus' feed

ing 'all the people...in groups ofhundreds and fifties' outdoors on 'the

green grass' (Mk6.39-40). In the miracle of loaves and fishes, Jesus feeds

five thousand, a larger partythan Herod's. The double motif of death and

the life-giving feast returns in the passion and the Last Supper, through

which Jesus continues to feed his faithful.

But still, why the women? What need is there for a peculiarly malevolent

Herodias and her dancing daughter to bring John's death about? Usually

regarded as an unaccountable doubling of her mother, the daughter

gestures towards the action of the New Testament while her mother sums

up the connection to the Old. As John Bowman observed (1965: 154),

Herodias confirms the identification of John as Elijah to Jesus' Messiah.

Her daughter links Jairus's daughter,risen,to the contrast between John's

death and Jesus' rising.

If, as Winkargues (1968) and Meier reaffirms, Mark's John is an 'Elijahincognito, a fitting forerunner ofa secret Messiah' (Meier 1980:384), then

5. is used at 1.31 for Simon's mother and at 2.9,11,12 for the man healed

ofa palsy, comes in forrisingbefore dayat 1.35, at 2.14 when Levi is called

and at 3.26 when Satanrisesagainst himself, and are used in Jairus's

daughter's story, in Herod's, dominates general discussions of rising

at 9.9, 10 (at 9.27 both verbs are used, coming first), 31; 10.34 (except

Bartimaeus, 10.49). The noun enters for discussions ofresurrection with theSadducees 12.18, 23, 25, but 12.26 has . In 13.8 is used for nations

rising against nations, and a compound of at 13.12 for childrenrisingagainst

parents. At 14, comes in exclusively, at 14.28 'after that I amrisen',;

14.42 'rise up, letus go', ; and 16.6 . The longer ending shifts at 16.9

to ?.

Matthew uses () after the Transfiguration at 17.9, unlike Mark, in the

discussion between Pilate and the Pharisees at Mt. 27.64 over what Jesus' disciples

will say if the bodygoes missing, and in the encounter between the women and the

angel at 28.6,7. Luke's two men use to the women at 24.6 to describe what has

happened and in 24.7, to cite what Jesus said would happen. John 20.9 uses to refer to the scriptures saying 'he mustriseagain' and ? at 21.14 to

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

7/26

JANES Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance 449

Mark needs scriptural evidence for that identification. Herodias supplies a

scriptural antecedent by evoking Jezebel, Elijah's principal persecutor.

Mark initially describes John as wearing 'the girdle of a skin about his

loins' (KJV, Mk 1.6; NRSV, 'a leather belt around his waist'). That girdle

not only belonged to Elijah the Tishbite, but also served as the code that

identified Elijah to others when he was not present (2 Kgs 1.7-8). The

reader identifying John as Elijahfromthe girdle reproduces Ahaziah's act

of interpretation.

Mark also invents unspecified, non-existent scriptural evidence toidentify

John as Elijah. At the Transfiguration, when the disciples ask why it is

said that Elijah must comefirst,Jesus answers that Elijah has already come

and they have done what they listed, 'as it is written abouthim' (Mk9.11-13). As Matthew recognized when he dropped the phrase 'as it is written',

no such writing exists. Without Herodias, Mark's evidence for identifying

John as Elijah is reduced by half, to a leather girdle. Herodias supplements

the girdle and, in turn, produces Mark's oddly sympathetic Herod.

Although Herod affirms his responsibility for John's death, 'It is John

whom I beheaded', the episode lays the blame principally on Herodias,

who sought John's death and told her daughter what to ask. Herod, by

contrast, fears and hears John 'gladly'. In Kings, Ahab and Elijah meetwith hostility, but respect; Ahab recognizes the prophet of the god of

Israel. When Elijah demands the assembling ofthe prophets of Baal, Ahab

calls them together (1 Kgs 18.17-20). When Elijah predicts rain after

drought, he runs before Ahab's chariot to Jezreel (1 Kgs 18.46). When

Elijah predicts that dogs shall eat Jezebel and the offspring ofAhab, Ahab

repents, and Elijah turns the curse from him in his lifetime (1 Kgs 21.21-

29). When Ahab tells his wife Jezebel what Elijah has done, then, and

then only, is the prophet's life endangered (1 Kgs 19.1-3). Jezebel, at more

length, though to less effect than Herodias, also speaks her threat: 'So maythe gods do to me, and more also, if I do not make your life like the life of

one ofthem by this time tomorrow'(1 Kgs 19.2). Elijahflees;John cannot.

Like Herod, Ahab's position towards the prophet is fundamentally sympa

thetic and respectful; the prophet's life is threatened only whenhe crosses

Ahab's wife.

What is narrative action in Kings, the narratorasserts in Mark, insisting

on a sympathetic Herod no one else saw in Herod's actions relative to

John: arrest and beheading. Every other source that mentions Herod(Josephus, Matthew, Luke, even Mark's Herod himself) rejects Mark's

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

8/26

450 Journal for the Study of the New Testament28.4 (2006)

parallel diminishes, taking with it textual confirmation for John as Elijah.

Markknows what everyone knows: John was murdered bya ruler married

irregularly to a wickedly adulterous woman, but Mark also knows that

John is Elijah. It would be surprising ifMarkhad not tweaked the storytoenhance the scriptural parallel.

If Herodias is necessary, her daughter's dance is even more so. Allusion

through Herodias links the Gospel to earlier scriptures (the old); her

daughter'sdance links deathtoresurrection(thenew). Commentators usual

ly veer offto the (unlikelihood ofthe dance, thesource oftije king's promise

in Esther, Girard's mimetic desire. Several have connected Herodias's

daughter and Jairus's. Janice Capel Anderson mentions Jairus's daughter

as the 'other Markan story involving a '(1992: 131). Dan Viasets corrupt sexualityHerodias and her daughteragainst restored

fertilityJairus's daughter and the woman with the bloody issue (1985:

108-11; Glancy1994:47-49). Linking Jairus's daughter to Jesus' empty

tomb and contrasting Jairus's daughter to Herodias's, Mark argues life's

overcoming death in minute narrative detail.

In the episode ofJairus's daughter, 'one ofthe leaders ofthe synagogue

named Jairus' asks Jesus to lay hands on his 'little daughter.. .at the point

ofdeath.. .that she may be made well, and live' (Mk5.22-23). En route,

Jesus' garments are touched by a woman 'which had an issue of blood

twelve years' (KJV, Mk 5.25; NRSV, 'who had been suffering from

hemorrhages for twelve years'). Jesus feels power go out ofhim, a loss of

life force that heals her, drying up her fountain of blood, making her

whole. As the woman confesses to him and he commends her faith, word

arrives that the daughter ofJairus is dead. There is no point in troubling

'the teacher any further'. Jesus insists that they should 'not fear, only

believe' (Mk 5.36); the first phrase will be echoed twice at his empty

tomb. Accompanied by three men, as by three women at the empty tomb,Jesus rebukes those at the door for weeping unnecessarily' [t]he child is

not dead but sleeping'and they 'laughed at him'. Taking the girl by the

hand, he says,

'Talitha cum... Little girl, get up!' [KJV, 'arise', ] And immediately

the girl gotup [KJV, 'arose', ] and began to walk about []

(she was twelve years ofage). At this theywere overcome with amazement.

He strictlyordered them that no one should knowthis, and told them to give

her something to eat (Mk5.41-43).Point by point, commentators have puzzled over this narrative, for it

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

9/26

JANES Whythe Daughter ofHerodias MustDance 451

Herodias's. Why are we told the age ofJairus's daughter (Mk5.42)? Why

is Jesus interrupted on his way to the dying girl by the woman with the

bloodyissue? Whyhas she been bleeding for twelve years, as long as the

girl has been alive, as ifthe bloody issue were a daughter (Mk5.25-34)?

Why is the daughter to be given something to eat to end the episode

(Mk5.43)? Why does Jesus say to them all, 'Do not fear, only believe'

(Mk5.36)? All those details, her name, her age, her meal, Jesus' words,

vanish in Matthew's retelling (Mt. 9.18-25), so iftheyserve a purpose, it

was not one Matthewnoticed. Yet preciselythose otiose details establish

a system ofparallels, or contrasts, with the murder of John.

Like the daughterofHerodias (andEsther, who savedher people), Jairus's

daughter is called , 'little girl' or 'young girl', the diminuitive of. Unlike Herodias's daughter, her age is specified: twelve years, and

Jesus calls her bythe gender neutral 'child',TO. Like thedaughter

ofHerodias, she is known bythe name ofher influential parent.6Like the

daughter ofHerodias, she responds to Jesus' command 'immediately'

(), as the daughter acts on her mother's suggestion and asks for the

head 'immediately' (eu6u)andthekingsends fortheexecutioner'immedi-

ately' (). After a commotion ofwailing and grief, Jairus's daughter

'immediately got up [KJV, 'arose'] and began to walk about' (Mk5.42, ). In a swirl of festivities and

identical word order, Herodias's daughter 'came in, and danced' (Mk

6.22, ' \ ,

literally 'his daughter Herodias having come in and danced'). In both

phrases, the second verb suggests expansive, room-covering movement,

through and across space. Jairus's daughter does notjust get up and walk

(), she gets up and walks about(). Herodias's glides in

6. The divide between literary criticism and biblical scholarship is so deep that

many literarycritics writing on 'Salome' seem unaware that the 'nameless' daughter of

Herodias is actuallynamed 'Herodias' in the earliest Greek manuscripts (Sinaiticus and

Vaticanus, fourth century). The preferred reading of the Nestle-Alandand UBS Greek

texts is 'his daughter Herodias', ' , followed in the

NRSVand other modern translations. Other early,fifth-centurymanuscripts read

' , 'the daughter ofHerodias herself or 'the daughter

of the said Herodias' (KJV). The frequent complaint that 'his daughter Herodias' makes

the girl Herod's biological daughter is anachronistic. As the daughter of his wife

Herodias, the girl is his daughter, of his family (Anderson 1992: 121 n. 26; Aland1966: Mk 6.22 n.;Nineham 1964:175). 'His' daughter reinforces the linkbetween the

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

10/26

452 Journalfor the Studyofthe New Testament28.4 (2006)

participial verb forms. Jairus's daughter is to be given something to eat.

Dancing at a banquet, Herodias's daughter wants a head in a dish, as ifit

were something to eat.

Although the age ofHerodias's is not specified, her actions,

pleasing the king, identifying with her mother's desires, and adding her

own details to the request for the head 'at once.. .on a platter', place her

near womanhood, like the twelve-year old in the previous episode. The

banquet itselfis a birthday(or anniversary) banquet. Though Herod's age

is not divulged, and it has been suggested that may refer to the

anniversaryofa death (Graham 1991:152), this celebration counts years.

As Ren Girard observes, the text has very little descriptive detail, so the

verse in which the daughter comes in 'immediately with haste to the king[asking] at once the head ofJohn the Baptist on a platter' in direct, not

indirect discourse, is especially striking for its suddenflurryofadverbs

(emphasis added; 1984:314). Hearing that voice and seeing that movement

dramatize the parallel between Herodias's and Jairus's daughters, turning

one's numbered years into the other's behavior. With that voice and that

movement the turns twin.

The dancing daughter who brings death makes visible the dead

daughter, rising to life. The woman healed ofblood anticipates the bloodywoman Herodias, to whom the head is delivered, while the woman healed

and child revived are held in a mother-daughter relation by the number

twelve. Unless Herodias's daughterdances foraplatter, Jairus's daughter

walks and eats when she rises to no particular purpose, and Jesus antici

patestheangel'swarningwithout anyone's noticing. Mark's two daughters

form the crux ofthe gospel message: life against death. The only other

person this Gospel raises from the dead is Jesus himself.

The resurrection of Jairus's daughter is the act byJesus that heralds his

own resurrection(like the resurrection ofLazarus in John), as the Baptist'sdeath and tomb are those that Jesus overcomes. The two earliest endings

of Mark recognize this structure. What we call 'the Gospel of Mark' Mark

calls 'The beginning of the good news ofJesus Christ' (1.1), that is, the

Gospel's prehistory, what happened before the resurrection. Ending at

16.8 requires the 'belief that Jesus demands ofJairus to assuage the fears

and undo the silence of the women at the empty tomb. At the tomb a

young man says, 'Do not be alarmed [ ].. .he has been raised

[, KJV, 'is risen', 16.6]'. The three women are not convinced; theGospel ends with the women, afraid, . At the deathbed of

' ' f

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

11/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 453

(5.36). Jesus uses not the angel's word, but that on which the

Gospel ends: , . What remains to be spoken is the belief,

the gospel, that motivates Mark's narrative: 'he is risen'. What Mark's

auditors, and the women, must now do is 'only believe'. Pronounced by

Herod, announced by the angel, that good news awaits articulation and

fulfillment in readers and hearers.

In the shorter ending, two verses added to 16.8, the women speak to

those around Peter, and Jesus sends out the apostles again. The shorter

ending recurs to the first sending out of the apostles, within which the

Baptist's death is embedded. After Jesusdies, they do not come backto him

as they did before, but go out from him forever: 'And all that had been

commanded them they [the women] told briefly to those around Peter.And afterward Jesus himselfsent out through them,fromeast to west, the

sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.' There is no

bodyto lay in a tomb; there is, instead, the kerygma that rises from it.

The current longer ending of Mark, 16.9-20, is a pastiche of elements

from other Gospels that appears at the end ofthe second century. Bythen,

Mark's structurehadbeenblurredby the other Gospels he inspired. Merged

with them, he is, like John the Baptist, appropriated for a tradition he did

not know but helped create.Two issues remain: what happens in the other Gospels, and does this

account have any implications for Mark's historicity? The other Gospels

take over Mark's meanings without perceiving the relationship between

his meanings and his narrative structure. Luke and Matthew assert the

Elijah-John identification and kick away the scaffolding that supports the

identification in Mark. Matthewtells the story, Luke omits it. Oddly, the

Gospel that most closely reproduces Mark's method is John.

Generally praised for his revisions of'Mark's rambling story', Matthew

hashes Mark's careful structure ofjuxtapositions. The apostles are sent

out four chapters earlier (Mt. 10); the daughter of Jairus is raised five

chapters earlier, and loses her father's name, her age and her meal (Mt.

9.18-25). Nor does Jesus speak his remarkable words: 'Do not fear, only

believe... Talitha cum... Little girl, get up [KJV, 'arise']'. Instead, in

Matthew, 'he took her bythe hand and the girl got up [KJV, 'arose']' (

TO , Mt. 9.25). Matthew does not require Mark's

suggestive parallels because he makes what Mark implies fullyexplicit.

John is identified as the voice in Isaiah: 'This is the one of whom theprophet Isaiah spoke' (Mt. 3.3). Jesus himself asserts that John is the

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

12/26

454 Journal for the Study of the New Testament28.4 (2006)

prophesied untilJohn came; and if you are willing to accept it, he is Elijah,

who is to come' (Mt. 11.13-14). When Jesus says, 'Do npt be afraid', it is

the risen Jesus speaking to the women fleeing the tomb, fearfully and

joyfully ( , Mt. 28.10, repeating the angel's phrase at 28.5).

Preserving the execution episode, Matthewdiminishes female responsi

bility whileretainingthepersistenceofHerodianhostility to Jesus, manifest

from birth. As Winkputs it, 'All form a single rankof opposition' (1968:

28). Herod's father, Herod the Great, threatened Jesus' childhood at

Bethlehem; his brotherHerodArchelaus forced Joseph to settle in Nazareth,

so Herodthe tetrarch destroys John and threatensJesus' maturity. Develop

ing Wink's account, Meier argues a complex theological role for John in

Matthew, as a parallel-yet-subordinate prophet, announcing with Jesus thekingdom prior to its creation in the church. Altering Mark and auguring

the church's growth, John's disciples come after John's death to Jesus,

who withdraws from the public scene, equally marked for martyrdom

(1980: 400). Like Wink(1968: 27), Meier does not notice the narrative

problems Matthew inadvertently introduces by his changes.

Shrinking the now much less significant storyfrom sixteen to twelve

verses and seeming to smooth its positioning, Matthewintroduces a logical

problem at the beginning and a chronological one at the end. Instead ofHerod's hearing ofJesus' mighty works as the apostles spread through the

land, Matthew's Herod hears ofJesus as he fails to perform miracles in

his own country. 'And he did not do many deeds of power there, because

of their unbelief. At that time Herod the ruler heard reports about Jesus'

(Mt. 13.58; 14.1). The skepticism ofJesus' countrymen abuts strangely

with Herod's immediate conviction, stated onlyonce, that 'This is John

the Baptist; he has been raised from the dead... ' (KJV, 'is risen', ;

Mt. 14.2). Mark's alternative identifications ofJesus asElijah or one of

the prophets disappear, although they return prior to the Transfiguration

(Mt. 16.13-14).

Seeming smoother than Mark's, Matthew's conclusion introduces a

chronological impossibility. As Terence Donaldson shows, wistfully

desiring afirst-centuryreader who would reintroduce Herod to end the

flashback, Herod's flashback never closes (1999: 35-48). After John's

disciples buryhis body, they go tell Jesus, who withdraws into a desert

place and shortly feeds the five thousand. 'His disciples came and took the

bodyand buried it; then they went and told Jesus. Now when Jesus heardthis, he withdrewfromthere in a boat to a deserted place by himself (Mt.

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

13/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 455

it begins. Events take up from John's death, notfromHerod's memory of

beheading John, where the account began.

With his Herod hostile and Elijah disclosed, Matthewerases the strong

lines of the Ahab/Jezebel parallel. Although Matthew's Herod puts Johnin prison 'for Herodias' sake', the verse on her quarrel with John is missing.

Moreover,herfrustrateddesire to kill John becomes her husband's. Unlike

Mark's sympathetic Herod, Matthew's Herod wants to kill John but fears

the multitude: 'he feared the crowd, because they regarded him as a

prophet' (Mt. 14.5).

Although Matthew's fearful Herod resembles Josephus's aggressive

Herod, who kills John for his popularity (Ant. 18.118), Mark may have

suggested the variant. In the dispute with the Pharisees (Mk11.29-33)Mark affirms that the crowd regarded John as a prophet and the Pharisees

feared the crowd. Asked whether John's baptism was from heaven or 'of

human origin', the Pharisees refuse to answer, unable to say'from heaven'

because Jesus will ask why they failed to follow John; unable to say 'of

human origin' because 'they were afraid of the crowd, for all regarded

Johnastruly aprophet'. The motive Markassigns to the Pharisees, Matthew

assigns to Herod.

Having losther good twin, the daughter ofHerodias becomes lesspromi-

nent, but more complicit. Losing her going and coming to consult about

what to ask, she is 'Prompted by her mother' (KJV, 'before instructed of

her mother' has been an influential translation of

.) Herfluttery deleted, she demandsfirmly,'Give me the

head of John Baptist here on a platter' (Mt. 14.8). Matthew takes the story

fromMarkas almosthistory,freelychanges where he disagrees, and notices

no meaningful connection between daughters or bloody women. Instead,

the episode continues to contrast death and resurrection, the world and the

kingdom of God, but narrates in its plotting the drawing of others' disciplesto Jesus.

Luke drops the story of the Baptist's death like a stone, while preserving

in another place what evidently seemed its main point, the identification

of John as Elijah to Jesus' Messiah. To make that identification, Luke

replaces Herodias andher daughterwith a different pair of female relatives,

the cousins Elizabeth and Mary. Like Herodias and her daughter, one is

married and older (past childbearing), the other unmarried and virginal.

Gabriel announces first to John's father, then six months later to Jesus'mother, the identities of Elijah (Lk. 1.17) and Christ (Lk. 1.32-33, 35),

iti i f ll M l hi' Elij h (M i 4 5 6 Lk 1 17) Th ft

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

14/26

456 Journal for the Study of the New Testament 28.4 (2006)

Luke lets others' identifications of Jesus as the Christ or Elijah slip back

and forth or vanish altogether.7

Like Matthew (whose John resists baptizing Jesus, but obeys him [Mt.

3.13-15]), Luke is embarrassed by the baptism. As has often been pointedout, he arranges his narrative so that Jesus is baptized by nobody in

particular in the verse immediately after John is put into prison (Lk. 3.21 ).

'The baptism of John' recurs as an inferior baptism in Acts (Acts 18.25;

19.3-5), yet John also anticipates Jesus' teachings in the sharing of the

cloak (Lk. 3.19)andthepracticeofprayerhismodel motivates the request

for the Lord's prayer (Lk. 11.1). Compared to Mark, Matthew and John,

Luke'streatmentofJolmiscompletelyincoherentandextremelyinteresting,

but Mark's 'Elijanic secret' is Luke's startingpoint, even more explicitlythan it is Matthew's. If Matthew identifies John as Isaiah's 'voice in the

wilderness' and later as Elijah, Luke identifies him as Elijah before he is

born.

Luke's motive for deleting the story seems to be its misogyny. Not only

does Luke make Mark's theological point through good women, but he

also erases Herodias's responsibility for John's arrest. He diminishes the

roleofthemarriageandsexualityinbringing about John's deathby attacking

Herod for other crimes beyond the marriage: 'But Herod the ruler, who

had been rebuked by him because of Herodias, his brother's wife, and

because of all the evil things that Herod had done, added to them allby

shutting up John in prison' (Lk. 3.19-20, emphasis added). Herodias's

marriage remains irregular, but it no longer bears the responsibility for

John's death that it does in Mark and Matthew. The marriage is only one

7. Because ofthat slippage, Kazmierski asserts that Luke doe¬ apply the Elijah

model to the Baptist (1996: 99,117). Accurate relative to the body of the Gospel, that

argument requires ignoring the Gospel's opening assertion ofthat identity. In Luke,

Jesus' disciples think he is Elijah. They expect him to burn up a Samaritan town's

inhabitants 'as Elijah did'. (Firefromheaven protected ElijahfromAhaziah, 'the king

of Samaria's', companies of soldiers [Lk. 9.54 n. g; 2 Kgs 1.10, 12].) When John is

introduced baptizing, his followers wonder not if he is Elijah, but if he is the Christ

(Lk. 3.15). In Luke, the angels and the reader know who is who in the Elijah/Christ

contest, but among disciples and populace the question is open, and Luke suggests that

fluidity of identification. Wink argues that Luke has an Elijah midrash, rather than an

identification of Elijah as Baptist, Jesus as Christ (1968: 42-46). John's preaching

resembles Jesus' more than in any other Gospel; he instructs his hearers about cloak-sharing as Jesus does his (Lk. 3.19). Jesus' disciples ask him to teach them to pray the

way John did his disciples and the result is the Lord's prayer (11 1) Charles H H

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

15/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 457

of'all the evil things' Herodhas done, and not even the worst. Luke system

aticallyprovides meliorative images of women's conventional roles of

motherhood, service, prophecy and discipleship. The demonized sexuality

ofthe Herodias fable has no place among his Marys, Marthas, Elizabeths

and Annas. So he drops it.

Although he drops the wicked women, Luke does not drop Herod's

hearing ofJesus or beheadingofJohn, themomentthat introduces theflash-

backto the execution in Markand Matthew. Preserving Mark's placement

ofthe episode immediately after the raising ofJairus's daughter and the

sending out ofthe twelve, Luke omits only the skepticismofJesus' country

men. Herod comments on Jesus' identity and his beheading John, and then

the disciples return, as in Mark and Matthew, to feed the five thousand(Lk. 9.10-12; Mk6.30-32; Mt. 14.13). The flashback is simply excised

from its place in Mark, as Delorme suggested might easilybe done. Luke,

however, radically transforms Herod's response. A first-century reader

after Terence Donaldson's heart, Luke writes as if he were intent on

closing the aperture opened byMatthew.

Once again, Herod hears ofJesus, but this time the positive Herod of

Markand Matthewis 'perplexed'. Others have answers; Herod has onlya

question.Around

him some say of Jesus 'that John had been raised[] from the dead; by some that Elijah had appeared, and by others

that one ofthe ancient prophets had arisen []' (Lk. 9.7-8). Luke's

Herod does not believe anyofit. Mark's Herod twice repeated that Jesus

was John risen again; Matthew's said it once. Luke's Herod changes the

tune. Dismissingreincarnation, uninterested in resurrection, with no regrets

over beheading the Baptist, he sets up his later encounter with Jesus,

unique to Luke's Gospel: '"John I beheaded, but who is this about whom I

hear such things?" And he tried to see him' (Lk. 9.9; KJV, 'desired to see

him', , literally 'sought').The superstitious identifications belong to those around Herod, who

seems a skeptical empiricist, but becomes a miracle grubber himself when

given the opportunity. When an excited Herod does meet Jesus, he finds

Jesus' refusal to answer or to perform any miracle less gratifying than

Mark's eager Herod (Lk. 23.8-9; the echo is not verbal, but semantic).

Reintroduced into the narrative only to be disappointed, Luke's Herod

takes over the mockeryofJesus that the other Gospels assign to Pilate and

the Romans. HerodandPilate forge apolitical alliance over the condemned,gorgeously arrayed bodyofJesus, making 'friends with each other' where

' f '

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

16/26

458 Journal for the Study ofthe New Testament28.4 (2006)

Luke contrasts the worldlypower and wealth of Herod and Pilate with the

gospel of sharing carried by Jesus and John. Reworking Mark, Luke's

ironic structure proposes a Herod who never learns the answer to the ques

tion the reader does not need to ask.The Gospel of John improves on Luke in finding the story ofHerodias

andher daughter so completelybesidethepointthatnoteven Herod appears.

Living in oblivion, the whole Herodian family vanishes. Herod does not

even secure John's arrest. John 'had not yet been thrown []

into prison', a passive construction (Jn 3.24). When asked, John denies he

is Elijah, his death is not narrated, his imprisonment is indefinitely deferred.

Nor does John baptize Jesus or bear the designation 'the Baptist' (Meier

1980:385). He is merely 'John' (a designation not followed below, to avoidconfusion between the baptizer and the evangelist). Stunningly, however,

John uses the Baptist-as-if-living to precede the greatest ofJesus' signs,

theresurrectionofLazarus. He thus reproduces Mark's juxtaposition ofthe

Baptist's death and the raising of Jairus's daughter, but turns it entirely

towards life.

As in Mark, the Baptist's preaching in John is restricted to announcing

the coming one and identifying Jesus as the one to come. In Mark, the

Baptist preaches 'the baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins'

and the coming of 'one more powerful than (Mk 1.4,7). When John is

imprisoned, Jesus begins to preach 'the good news of God... "The time is

fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in

the good news'" (Mk 1.14-15). Evidently, the One being come, the

kingdom is near, the time fulfilled, arelationmarkedby the minimal differ

ences between what Jesus says and what John says. In Matthewand Luke,

the Baptist's preaching has much more scope: threatening and scourging

in Matthew, sharing cloaks and prayers in Luke. In John, the Baptist is re-

restricted to identifying Jesus as the bridegroom, before whom he mustdiminish.

Although the Baptist's death is never mentioned, Jesus speaking of

John slips from the present into the past tense, after 5.32:

IfI testify[] about myself, mytestimonyis [] not true. There

is [] another who testifies[] on my behalf, and I knowthat

his testimonytome is[] true [allpresenttense]. Yousent []

messengers to John, and he testified[] to the truth [perfect

indicative, some time in the recent past, as if that testimony could be

repeated in the present]. Not that I accept such human testimony, but I say

thesethings so that you maybe saved. [The passage nowmoves entirely into

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

17/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 459

Hewas[] a burning and shining lamp, and you were willing[,

aorist indicative] to rejoice for a while in his light. But I have a testimony

greater than John's. The works that the Father has given me to complete

[, KJV, 'finish'], the veryworks that I am doing, testify on mybehalf that the Father has sent me (Jn 5.31-36, emphasis added on verbs).

As in Mark, Matthewand Luke, the Baptist's presence is initiallyneces

saryto identify Jesus, although Jesus later affirms that his own testimony

to himselfis sufficient (Jn 8.14). Evenhere, where the Baptist's testimony is

invoked, Jesus affirms that his works bear 'greater witness' than John's

testimony. Ofhis works, the greatest is the resurrection of Lazarus. So too

onthecross Jesusfinishesthe works hehasbeen sent to 'finish' ():

'It is finished' (, Jn 19.30).Justbefore the raising ofLazarus, Jesus citeshis works again. InJerusalem

he is asked, as the Baptist was, if he is the Christ (Jn 1.20-21 ; 10.24). Jesus

replies that he and the father are one (a just inference from Mark's scrip

tural citations and the prophecies of his Baptist, see belown. 9). About to

be stoned for blasphemy, Jesus cites his works:

If I am not doing the works of my Father, then do not believe me [

].But if I do them, even though you do not believe me [],

believe [] the works, so that you may know and understand[; 'believe', (Vaticanus), (Alexandrinus

and others)] that the Father is in me and I am in the Father' (Jn 10.37-38).

The great workhe is about to do, that will bring on his death in this

Gospel, is the raising ofLazarus. Yet before he performs it, in what seems

a most unnecessary narrative splicing, Jesus withdraws across the Jordan,

to the place where John had been baptizing earlier, and he remained there.

Manycame to him, and they were saying, 'John performed no sign, but

everything that J.ohn said about this man was true'. And many believed inhim there. Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany... (Jn 10.40-42;

11.1).

This moment is commonly read as instancing John's hostility to and

contentions with followers ofthe Baptist. Earlier in the Gospel Jesus and

John compete over such matters as who had more water availableJohn

(Jn 3.22-23)and who baptized more followersJesus (Jn 4.1-2). Here

the people insist the Baptist gave 'no sign'. Jesus gives many, and he is

about to surpass himself. Revealing his followersas

deluded andsignless,the episode seems to denigrate the Baptist.

Yet the passage also juxtaposes the Baptist as living with the great

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

18/26

460 Journal for the Study ofthe New Testament28.4 (2006)

byJohn, seems nevertheless to drawstrength from the place where John

was baptizing. Reworking Mark's contrast between life and death, Jesus

withdraws to the water where 'John had been baptizing earlier'. Not only

does Jesus return to that place but, hearing of Lazarus's sickness, he waits

there: 'he stayed two days longer in the place where he was' (11.6). On

the (third) day, Jesus moves to awaken Lazarus. Simultaneouslyinvoking

the Baptist's witness and leaving him behind, Jesus gives life to Lazarus,

repeating more dramatically the raising of the daughter of Jairus, also

interrupted until the sick person has died.

As in Mark, Jesus affirms the dead is only sleeping and to be awakened

(Jn 11.11). As in Mark, at issue is belief, made fullyexplicit by John:

Jesus said unto her, am the resurrection, and the life. Those who believe

[] me, even though theydie, will live, and everyone who lives and

believes [] in me will never die. Do you believe [] this?'

(Jn 11.25-26).

From the place where the Baptist was, Jesus moves to offer his greatest

sign and its requirement, 'only believe' [, Mk5.36]. Although

Mark'sJohn baptizes Jesuswithout comment and John's Baptist comments

at length without baptizing Jesus as a narrative event (Mk 1.9; Jn 1.30-

34), both confirm the indispensability ofthe Baptist to the identification ofJesus and thus to early Christian theology.

For the 'historical' John and Jesus, the implications of this analysis are

not helpful. The problem arises when we consider that the only evidence

foranyconnectionbetween Jesusand John is Mark. IfJohn is indispensable

to Mark's argument, one must ask ifMarkhas not simply appropriated the

Baptist for his own purposes and, in effect, taken his head as a Christian

trophy. Josephus suggests no connection between Jesus and John, even as

he makes clearthecontinuingprominenceof John in the Jewish community(Ant. 18.116,119). For the Jesus cult, Markmay simply have appropriated

John as a prominent person to serve a signal role, the suffering Elijah to

announce the suffering Christ. Not even the Gospel of John lets Jesus be

the only witness to himself: he needs scriptural authority, he needs ante

cedents, he needs a forerunner, even when he preexists the one who

comes before (Jn 1.15).

To the argument that the baptism of Jesus by John must be a historical

fact because it so embarrasses the other Gospel writers (Kazmierski 1996:

47-48), Mark's having asserted the baptism is itselfsufficient to generate

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

19/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 461

the embarrassment.8 Certainly, Mark makes no claim for any connection

beyond the baptism; the episode is entirely self-contained. The Baptist

makes no comment about the dove or voicefromheaven; Jesus disappears

into the wilderness and reappears only after John's imprisonment. John

may have baptized or inspiredJesus, or Jesus may have been a disciple of

John, who then went his own way (see Badke 1990; Mason 1992; Murphy-

O'Connor 1996; Vaage 1996). He may have, but it may equally well be

the case that Mark appropriated John as Elijah for his Lord and so led the

other Gospel writers inevitably into midrash, developing and disguising a

non-existent relationship.

To conclude with a return to the question from which we began, the

story ofHerodias and her dancing daughter appears in only two oftheGospels because the Gospels are not histories, but Gospels, each of which

has its own peculiar interpretation ofthe meaning of Jesus as Christ and

its own view of whatmatters most in his message. For two ofthe Gospels,

Luke and John, the story, which originates in Mark, has no place. Using

Mark's Gospel as his narrative outline, Luke omits the story deliberately

and so smoothly that no gaps or holes appear,as Delorme predicts. Although

'sweep[ing] away legendary material' and 'de-emphasiz[ing] the role of

the Baptist' have been proposed as Luke's motives for deletion (Murphy2003:72), far more probable is the misogynist thrust ofthe Markan story,

given Luke's emphasis on meliorative roles for women throughout his

Gospel. Replacing a story of wicked women manipulating a king, Luke

resituates the Herod episode in the larger political context linking Rome

and Judea, much as his account ofJesus' birth at the time of Quirinus's

census connects events in Palestine with events in Rome. In removing

Herodias's responsibility for the death of John, Luke re-characterizes

Mark's superstitious Herod as a skeptic, curious about this new wonder-

8. Kazmierski observes that the 'problematic nature ofthe tradition' convinces

'even the most skeptical of modern scholars that the baptism ofJesus byJohn is indeed

one of the most reliable historical traditions of the Gospels'. Grounds for that

embarrassment are clearly laid out in other New Testament documents. At Corinth Paul

confronted the problem that believers identified themselves with their baptizer rather

than Jesus: 'each of you says, "I belong to Paul", or"I belong to Apollos", or "I belong

to Cephas", or "I belong to Christ". Has Christ been divided? Was Paul crucified for

you? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul? I thank God that I baptized none of

you, except Crispus and Gaius, so that no one can say that you were baptized in myname' (1 Cor. 1.12-15). The Lukan account in Acts ends with a rebaptism in the name

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

20/26

462 Journal for the Study ofthe New Testament 28.4 (2006)

worker Jesus. Luke follows up that shift with an episode unique to his

GospelthemeetingofHerod and Jesus and the consequent reconciliation

of Herod and Pilate, in which the powers-that-be come together through

their opposition to Jesus (Lk. 23.6-12). Luke's graceful hostility to the

great, his urbane preference for the poor and marginalized, his elegant

inclusion ofthe great powers he despises are thus carried through at two

levels by his omission of Mark's story. He elevates Elizabethand Mary as

carriers ofthe Elijah/John, Lord/Jesus identification, and he implicates

Herod in Rome's deadly skepticism.

The Gospel of John forgoes Mark's narrative outline, though it may use

pseudo-biography as form because of Mark's influence and example. John

enlarges theBaptist'sMarkanrolefrommessenger to witness and eliminatesthe Baptist's death along with his baptism ofJesus. Instead of baptizing

Jesus, John talks about him on three days,firstto the Pharisees while he is

baptizing, the 'next day' when he sees Jesus and 'bears record' that he

saw the spirit descending upon him, and 'Again the next day' when he

says, 'Behold the Lamb of God' (Jn 1.15-28,29-34,35-36). Although the

Baptist was baptizing when he saw Mark's dove descend, John does not

say the Baptist baptized Jesus (Jn 1.30-34). John also eliminates the entire

Herodian family: the dispute in John is not between worldly powers andGod's son and messenger, but between those who would make John the

Messiah and those who recognize with John that Jesus is the son of God

(Jn 1.19-21,25,34). Although John's imprisonment is mentioned, it has

not yet occurred within John's Gospel and it is not performed by anyone;

it occurs in a passive construction (Jn 3.24). The discourse that follows

theimprisonment-that-has-not-yet-occurred,onJohn'sdecreasing,never-

theless motivates a withdrawal by Jesus like that in Mark, Matthew and

Luke: 'Now when Jesus learned that the Pharisees had heard, "Jesus is

making and baptizing more disciples than John"...he left Judea and

started back to Galilee' (Jn 4.1-3). The Baptist reappears a third time in

John, when Jesus delays for three days to return to raise Lazarus, at 'the

place where John had been baptizing earlier, and he remained there' (Jn

10.40). Although the Baptist's death plays no role, the Baptist's witness

remains indispensable to Jesus' identification and his works.

John's Gospel is often taken as recording competition between John's

disciples andJesus'. That sense of competition may derivefromthe tension

between a prexistent, self-manifesting Lord and the need for a witness tohim in John. Not only is John (Baptist) necessary for the first revelation,

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

21/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 463

recurs in John's characteristic triads. John throughout is concerned with

eternal life; he has no interest in working out a contrast between life and

death. That is not his project. So the Baptist, who dies spectacularly in

Mark and Matthew and offstage, beheaded, in Luke, in John fades away,

neither living nor dead, merely 'decreasing'.

Matthew takes the story from Mark and reduces it to dimensions

appropriate to his projectJesus as king and son of David, harried by

Herods, producing the new Torah as the basis for his church. Revising

without re-imagining (as Luke did), he introduces several implausibilities

in the placement ofthe episode within his own narrative, as ifit were a

tale good enough to include, but not important enough to think about.

Asserting what Mark implies, Matthew finds other ways than Jezebel toattach Jesus to the scriptures, including genealogy and multiple citations.

Interestingly, against the mother and daughter who procure John's death,

Matthew introduces Pilate's wife, interceding to prevent Jesus' death (Mt.

27.19).

This returns us finally to the point of origin, to Mark. As to historicity,

Mark's account is confirmed at most points by Josephus: Herod executed

John; his marriage to Herodias was irregular by current moral standards;

ambitious, influential, meddling and power-hungry, Herodias had adaughter (named Salome); John was revered from Herod's time to

Josephus's, more than half a century later (Ant. 18.116-19,109-10,136-

37, 240-55, 119). Herodias Josephus links to the Baptist's death only

indirectly, through Herod's divorce from another man's daughterin order

to marry her. Many, he reports, thought Herod's defeat by Aretas divine

vengeance for John's execution (Ant. 18.116); Aretas attacked because

Herod divorced Aretas's daughter to marry Herodias (Ant. 18.109-15).

Josephus links the divorce and the execution, not the marriage and the

execution. Other opponents ofthe marriage might have made more of it,yet although Josephus gives Herodias two long speeches on other matters

(Ant. 18.243-44, 254), he attributes the Baptist's execution entirely to

Herod. Josephus and Mark differ fundamentally over the points Mark

makes climactic: Herodias's responsibility and her daughter's dance, with

platter.

Did the story of the dance, like the interpretation of John as Elijah,

circulate in early Christian circles to be picked up by Mark? Although a

shared supper and baptism already define the community in Paul's time,no evidence earlier than Mark exists for the dance or the return of Elijah.

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

22/26

464 Journal for the Study ofthe New Testament 28.4 (2006)

Later, the other evangelists, with Mark open before them, do not feel

compelled by early Christian history or rumor mills to endorse Herodias's

special culpability.

Calling the story a sleazy rumor snatched up by Mark suggests that

Mark was not a writer, but a compiler, and that the story is isolated from

its context. Yet ofthe four Gospels, Mark's is the most compelling 'read'

as its emerging secret unfolds, dramatically, ironically, known already to

the reader, but not to the participants in the action. Comparisons to

Sophocles'Oedipus TyrannosmGnotwimGrted9and9 as so often with great

works, others itched to rewrite it, viz. Matthew and Luke. As to isolation,

the story has seemed anomalous, salacious, uniquely gory (to scholars

forgettingthecrucifixion),protruding oddly and horriblyinto the narrative.Yet the episode is not isolated thematically: it introduces the concept of

resurrection and the question ofthe identities of Jesusand John, crucial at

the Transfiguration. As Mark dramatizes the death, focusing on the

women, he reconfirms John's identity as Elijah and links not only John's

death, but also Jairus's daughter's resurrectionto Jesus' own resurrection.

Linking Jairus's daughter to Jesus as another resurrection wouldnot seem

important, except that the Gospel originally ends on echoes ofthe scene

raising Jairus's daughter.Even when first expanded, the ending of Mark's Gospel recalls the

episode in which John's death is intercalatedthe sending out of the

apostles. Through Mark's careful structure of details, incidents, inter

calations, juxtapositions and linguistic duplications, the two daughters,

one linked to life, fear and belief, the other to death, create an antithesis

that Jesus overturns.

It might be objected that this argument hinges on an accidental verbal

identity of different things. The incidents, called 'resurrection' or 'raising',

conflate aresuscitation(Jairus's daughter), a reincarnation (Herod'sremarkabout John), and a resurrection (Jesus), and the analysis treats them as

though they are all the same. The objection forgets that Mark has an

object in view in his narrative (specifically, the gospel of resurrection) and

that Markuses the same word for each of these events. Mark is establishing

connections by repetition and duplication for the gospel's sake; he is not

writing a treatise on different forms of revival from the dead. If he wanted

his readerto distinguishbetweenresuscitation, reincarnation andresurrec-

tion, he would have found different words for his different concepts.It might also be objectedthat this argument is purely inferential, created

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

23/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 465

same: insistingon the appropriateness ofstudying Mark'snarrative structure

as a guide to Mark's meanings and observing that Mark's narrative power

proceedsfromthe way he compels inferences. Mark's Gospel opens with

scriptural allusions that require inferences nowso obvious we forget they

are inferences. So Jesus is understood as 'you' in Mark's misquotation

from Malachi9

and as the Lord in the quotation from Isaiah, while John is

understood as the voice 'in the wilderness' (Mk 1.3) because in the next

verse he appears 'in the wilderness', baptizing (Mk1.4). Markasserts no

identities, but his structure makes the inference inevitable. That practice

of inference makes any discoveries the reader's own, convincing more

deeply than anything the reader may be told.

Herodias's daughter must dance to make death visible, bodied and foodfor faith. The little girl, her bloody mother and her platter linkhorror to

hope, thrusting John's severed head into women's hands. Three men

accompanyJesus when he raises Jairus's daughter; three women stand at

an empty tomb when Jesus is raised, ofwhom one bears the name of

Herodias's real daughter, Salome (Mk16.1), married to the Philip Mark

mistakenly identifies as Herodias's husband (Mk 6.17). Accidental or

purposeful, that coincidence marks yet again the difference between the

women who destroy John and the women whom the bodyescapes.

9. Markreads: 'As it is written in the prophet Isaiah, "See, I am sending my

messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way; the voice of one crying out in the

wilderness, 'Prepare the way ofthe Lord, make his paths straight'," John the baptizerappeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of

sins' (Nik1.2-4, emphasis added). Conflating Isa. 40.3 and Mal. 3.1, misquoted, Mark

changes Malachi's pronouns and his meanings. Malachi's ' is God and speaks of'me'

(not Mark's 'you'): 'See, I am sending mymessenger toprepare the way before me, and

the Lord whom you seekwill suddenly come to his temple' (Mai. 3.1, emphasis

added). In Malachi, 'me' is 'the Lord' who is suddenlyto appear, in his temple. In Mark,

the Lord speaks of someoneapartfromhimself, 'you', 'your way'. Mai. 4.5-6, repeating

the phrase promising return, names Elijah in the place ofthe messenger, but Elijah too

precedes not a person, but the verypresence ofthe Lord. Although we no longer notice,

Malachi and Isaiah would have found it very odd to be caught prophesying someonewho wears shoes or sandals'the thong ofwhose sandals.. .1 am not worthyto stoop

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

24/26

466 Journal for the Study ofthe New Testament 28.4 (2006)

Bibliography

Aland, Kurt et al. (eds.)1966 The Greek New Testament (2nd edn; New York: United Bible Societies).

Anderson, Janice Capel

1992 'Feminist Criticism: The Dancing Daughter', in Janice Capel Andersonand

Stephen D. Moore (eds.) Mark and Method(Minneapolis: Fortress Press):

103-34.

Aus, Roger

1988 Water into Wine and the Beheading of John the Baptist: Early Jewish-

Christian Interpretation of Esther 1 in John 2.1-11 and Mark 6.17-29

(Atlanta: Scholars Press).

Badke, William1990 'Was Jesus a Disciple ofJohn?', EvQ 62:195-204.

Bowman, John

1965 The Gospel ofMark: The New Christian Jewish Passover Haggadah (Leiden:

E.J. Brill).

Broadhead, Edwin K.

2001 Mark (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press).

Carrington, Philip

1960 According to Mark: A Running Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press).

Delorme, Jean1998 'John the Baptist's HeadThe Word Perverted: A Reading of a Narrative

(Mark 6.14-29)', Semeia 81: 115-29.

Derrett, J. Duncan M.

1985 The Making of Mark (2 vols.; Shipston-on-Stour, England: P. Drinkwater).

Donaldson, Terence

1999 "Tor Herod Had Arrested John" (Matt. 14.3): Making Sense of an

Unresolved Flashback', SR 28: 35-48.

Dottin-Orsini, Mireille

1996 Salom (Paris: Autremont).

Duran, Nicole Wilkinson

2002 'Return of the Disembodied or How John the Baptist Lost his Head', in

Gary Phillips and Nicole Wilkinson Duran (eds.) Reading Communities,

Reading Scripture (Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press): 277-91.

Girard, Ren

1984 'Scandal and the Dance: Salome in the Gospel of Mark', New Literary

History 15: 311-24.

Glancy, Jennifer A.

1994 'Unveiling Masculinity: The Construction of Gender in Mark 6.17-29',

Biblnt 2: 34-50.

Graham, Susan Lochrie

1991 'Silent Voices: Women in the Gospel of Mark', Semeia 54:145-58.

Kazmierski, Carl

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

25/26

JANES Why the Daughter ofHerodias Must Dance 467

Kuryluk, Ewa

1987 Salome and Judas in the Cave of Sex (Evanston, IL: Northwestern

University Press).

Mason, Steve1992 'Fire, Water, and Spirit: John the Baptist and the Tyranny of Canon', SR

21.2: 163-80.

Meier, John P.

1980 'John the Baptist in Matthew's Gospel', JBL 99: 383-405.

2000 'The Debate on the Resurrection ofthe Dead: An Incident from theMinistry

ofthe Historical Jesus?', JSNTll: 3-24.

Meltzer, Franoise

1984 Response to Ren Girard's Reading of Salome', New Literary History

15: 325-32.

Montefiore, C.G.

1968 The Synoptic Gospels (2 vols.; New York: KTAV Publishing House).

Murphy, Catherine M.

2003 John the Baptist (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press).

Murphy-O'Connor, J.

1996 'Why Jesus Went Back to Galilee', BRev 12:20-29,42-43.

Nineham, D.E.

1964 The Gospel of St Mark (Baltimore, MD: Penguin).

Ohler, Markus

1999 'The Expectation of Elijah and the Presence ofthe Kingdom ofGod', JBL

118:461-76.

Scobie, Charles H.H.

1964 John the Baptist (London: SCM Press).

Tatum, W. Barnes

1994 John the Baptist and Jesus: A Report ofthe Jesus Seminar (Sonoma, CA:

Polebridge Press).

Vaage, LeifE.

1996 'Bird-Watching at the Baptism of Jesus: Early Christian Mythmaking in

Mark 1.9-11 ', in Elizabeth A. Castelli and Hal Taussig (eds.), Re-Imagining

Christian Origins (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International): 280-94.

Via, Dan O., Jr

1985 The Ethics of Mark's Gospel in the Middle of Time (Philadelphia: FortressPress).

Webb, Robert L.

1991 John the Baptizer and Prophet: A Socio-Historical Study (Sheffield:

Sheffield Academic Press).

Wink, Walter

1968 John the Baptist in the Gospel Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press).

-

7/31/2019 Why the Daughter of Herodias Must Dance

26/26

^ s

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual useaccording to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and asotherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.

No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without thecopyright holder(s)' express written permission. Any use, decompiling,reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be aviolation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permissionfrom the copyright holder(s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of a journal

typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However,

for certain articles, the author ofthe article may maintain the copyright in the article.

Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specificwork for any use not covered by the fair use provisions ofthe copyright laws or covered

by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the

copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available,or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s).

About ATLAS:

The ATLA Serials (ATLAS) collection contains electronic versions of previously

published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS

collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association(ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc.

The design and final form of this electronic document is the property ofthe AmericanTheological Library Association.