Why do Liberal Democrats oppose the Child Trust Fund?

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

stuart-white -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

3

Transcript of Why do Liberal Democrats oppose the Child Trust Fund?

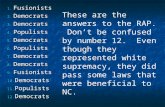

The Child Trust Fund(CTF) endows eachchild with a small grantat birth. This is paidinto a special savings

account, which is held in trust for thechild until he or she reaches maturity.The family of the child may make pay-ments into the account up to a ceilingof £1,200 per year, and there are plansfor additional state payments on thechild’s seventh and 11th birthdays. Theaim is ensure that each child entersadulthood with at least some capital tocall their own.

Introduced by Labour, the CTF isalso supported by the Conservatives.However, the Liberal Democrats wentinto the 2005 general election pledgingto abolish it. This remains party policy.

Quite why the Liberal Democratsoppose the CTF is a puzzle. The Liberalparty fought for the ideal of ‘ownershipfor all’ for much of the 20th century.The philosophical arguments for policieslike CTF appeal to impeccably liberalvalues. The reasons the LiberalDemocrats give for abolishing the CTFare very weak. So the LiberalDemocrats appear to be opposed, for no

very good reason, to a policy thatexpresses their own values and historicalcommitments. Perhaps by laying barethe puzzle, we may be able to spur theLiberal Democrats into a more consid-ered response to this innovative policy.

Historical�commitmentsLet’s start with the history. One of themost important books in post-warLiberalism is The Unservile State (Watson1957), a collection of essays thatexplain what was distinctive and valu-able about Liberalism at a time whenits political fortunes were at a very lowebb. In an introductory essay, ElliotDodds set out his view of what madeLiberalism distinctive:

‘...here as everywhere, on creating condi-tions favourable to the development of per-sonality, Liberals are necessarily distributists[...] Liberals therefore seek to spreadwealth, ownership, power and responsibilityas widely as possible. Thanks largely totheir initiative, much has already been doneto spread income [...] Little or nothing,however, has been done to spread property;yet this [...] is vital to the spreading of

public�policy�research�–�March-May�200724

© 2

007

The

Aut

hor.

Jou

rnal

com

pila

tion

© 2

007

ippr

Why�do�LiberalDemocrats�opposethe Child TrustFund?

The�Liberal�Democrats�have�long�argued�for�the�abolition�of�the�Child�TrustFund�–�Labour’s�prize�initiative.�Here,�political�philosopher�Stuart�Whiteargues�that�their�opposition�is�not�only�misplaced,�but�contradicts�their�ownvalues�and�historical�commitments.

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 24

choice and the creation of greater equality ofopportunity.’ (Dodds 1957: 20-21)

In emphasising the ambition to spreadthe ownership of wealth – not income,but property – Dodds was drawingattention to an ideal that had becomecentral to Liberal politics. Against asocialism that sought to concentrateproperty in the state, and aConservatism that sought to preserveindefensible inequality of private prop-erty, Liberalism aspired to a society ‘inwhich everybody will be a capitalist,and everybody a worker, as everybodyis a citizen’ (Liberal Industrial Inquiry1928: 261). More succinctly, theLiberal goal was ‘ownership for all’.

Numerous party committees soughtfrom the 1930s to the 1950s to fleshout this slogan. Parliamentary candi-dates fought on this platform. Theparty’s newspaper, Liberal News, ranheadlines such as ‘Liberals MEANOwnership for All’ and ‘RevolutionaryLiberalism Plans for the New SocialOrder’ (Liberal News 1958; 1959). Thelatter article explained that Liberalsdesire ‘Not an All-Absorbing State: Nota Land of Rich Tycoons: But a Societyfor All of Us.’ ‘The Liberal aim’ itargued, ‘is a widespread diffusion ofpersonal ownership so that all citizenscan have complete control over some-thing they can truly call their own.’

Liberal policy to spread ownershiphad three main elements: 1) taxation ofinheritance, but with preference for tax-ing the recipient of transfers rather than

the donor; 2) measures to increaseincentives and convenience for smallsavers; and 3) promotion of profit-shar-ing, employee share ownership andlabour participation in workplace andfirm management (‘co-ownership’).

Over time, however, new policyideas began to filter into party discus-sion. Many of these pointed towardswhat one might call a universal assetpolicy: a policy of directly endowingeach citizen, as of right, with a capitalstake. In a 1974 article in the Liberaljournal New Outlook, Dane Clouston, aLiberal parliamentary candidate, pro-posed a scheme of this kind. ‘TheLiberal Party’, Clouston argued, ‘musthave a policy for levelling up inheritedwealth, as well as levelling down’(Clouston 1974). Instead of merely tax-ing transfers of wealth, the state shoulduse the funds to ensure that every citi-zen receives at least some capitalbetween the ages of 18 and 30. Thebasic idea of a universal asset policy,with a history stretching back toThomas Paine, had re-emerged.1

Thatcherism prompted further radi-cal thinking on these lines. Throughcouncil house sales and privatisations,the Thatcher governments initiatedtheir own policy of spreading owner-ship. As the party that had traditionallystood for ‘ownership for all’, how couldthe Liberals (and their new SDP allies)respond to this? One response, whichwe see in SDP as well as Liberal partythinking, was to argue that Thatcher’spolicies did not spread ownership to all.Ideas circulated as to how to put a capi-tal stake into the hands of all citizens.

An early example is Samuel Brittan’sand Barry Riley’s proposal for ‘APeople’s Stake in North Sea Oil’, pub-lished by the Liberal-orientatedUnservile State Group (Brittan andRiley 1980). Brittan and Riley ask the

© 2

007

The

Aut

hor.

Jou

rnal

com

pila

tion

© 2

007

ippr

public�policy�research�–�March-May�2007 25

The�basic�idea�of�a�universalasset�policy,�with�a�historystretching�back�to�ThomasPaine,�had�re-emerged

1. Clouston continues to campaign for this policy. For information go to www.universal-inheritance.org(accessed January 2007).

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 25

question: what should be done with thewindfall of North Sea Oil revenues?Their answer: endow each citizen witha capital stake in the flow of North Seatax revenues. Britain could thereby‘take a giant stride towards a genuinepeople’s capitalism’ (Brittan and Riley1980: 1).

As SDP leader, David Owen arguedon similar lines that, if public utilitieswere privatised, this ‘should be done bygiving the shares free to every adult cit-izen [...] A free issue of shares would bea good precedent to establish for free-ing up the other monopoly state indus-tries and giving everyone a stake intheir future’ (Owen 1985: 18).

The SDP’s internal think tank, theTawney Society, produced one extreme-ly thorough report on proposals forachieving a more equal distribution ofwealth, which sympathetically consid-ered two universal asset policies,‘SuperStock’ and a ‘Citizens’ Trust’(Gravil (ed) with Mennell and Slavin1986).

Under the first proposal, developedby US lawyer Stuart Speiser, all busi-ness investment after a certain date isfinanced from bank loans. Firms issuenew shares – the SuperStock – equal tothe value of these loans. These sharesare initially owned by the banks, butownership passes to the population atlarge, on an egalitarian basis, as thebusinesses pay the loans. In time, thepopulation at large comes to own a sig-nificant amount of capital. Under thelatter proposal, each firm must pay aportion of its profits to a Citizens’Trust, which the Trust then uses to pur-chase shares in the firm. The Trustwould hold its shares on behalf of citi-zens, distributing dividends to them onan egalitarian basis, but people wouldnot be allowed to sell their shares.

Both of these ideas, SuperStock andthe Citizens’ Trust, fed directly intoPaddy Ashdown’s thinking, as the firstLiberal Democrat leader. In his book

Citizens’ Britain, intended to give an ide-ological lead to the new party,Ashdown argued that ‘We could bemuch more radical about popular shareownership – we could give every citizena stake in our economy’ (Ashdown1989: 129). Ashdown broadly endorsesJames Meade’s plan to develop a‘Citizens’ Share Ownership Unit Trust’holding, as a long-run goal, 10 per centof the assets of ‘all private sector enter-prises over a certain size’. Thus, asleader of the newly formed LiberalDemocrats, Ashdown enthusiasticallyendorsed the idea of a universal assetpolicy (in the form of the Citizens’Trust).

The�philosophical�argumentsLet us now turn to the philosophicalarguments for a universal asset policy.Within contemporary academic politi-cal philosophy, the case is set out inmost depth by Bruce Ackerman andAnne Alstott in their book TheStakeholder Society (Ackerman and Alstott1999). Ackerman and Alstott argue fora much more radical policy than theCTF. They argue for endowing eachUS citizen with a grant of US$80,000on maturity, paid for by taxes onwealth and inheritance. What is ofinterest here, however, is the ethicalconsiderations they give in favour ofthis kind of policy.

One consideration is that of equalopportunity. Ackerman and Alstott iden-tify a range of obstacles to equality ofopportunity: discrimination; unequalaccess to quality education; and inequal-ities in natural ability. But they alsopoint to unequal endowments of wealthin early adulthood. A lack of wealth atthis crucial time makes a huge differenceto overall life opportunities, as it affectsaccess to further and higher education,career experimentation, business set-up,and so on. Ackerman and Alstott arguethat a universal stakeholder grant is a

public�policy�research�–�March-May�200726

© 2

007

The

Aut

hor.

Jou

rnal

com

pila

tion

© 2

007

ippr

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 26

way of addressing this obstacle to equali-ty of opportunity. The basic argumentechoes the Liberal Elliot Dodd’s claimthat spreading wealth is vital to ‘the cre-ation of greater equality of opportunity’.

Perhaps given even more emphasisby Ackerman and Alstott, however, isthe value of personal freedom. Theyhave two concerns here. First, a lack ofproperty makes a person more depend-ent on others – their employer, or per-haps their spouse – for their income.This gives the other party a degree ofpower over them. Because it is verycostly for the property-less person toexit the relationship, the one with prop-erty is in a position to call the shots.Someone with their own property, how-ever, can more easily exit such relation-ships, and this exit option changes thebalance of power so that they are noteasily dominated.

Ackerman and Alstott make thepoint by citing a passage from JamesMeade, an economist with a long asso-ciation with the SDP, Liberals andLiberal Democrats: ‘A man with [...]property has [...] bargaining strengthand a sense of security [...] He can snaphis fingers at those on whom he mustrely for an income, for he can alwaysrely for a time on his capital’ (cited inAckerman and Alstott 1999: 25).

Second, property underpins our abil-ity to approach life reflectively and cre-atively. Every young person should beable to ask themselves seriously: ‘whatdo I want to do with my life?’ But a

lack of wealth in early adulthood canundermine our ability to pose this ques-tion in a meaningful way. As Ackermanand Alstott put it: ‘just at the momentwe expect young adults to makeresponsible life-shaping decisions, wedo not afford them the resources thatthey need to take a responsible long-term perspective. Forced to put breadon the table [...] almost all young adultsare squeezed into short-term thinking’(Ackerman and Alstott 1999: 35).

It is, once again, very striking howthese freedom-based concerns feature inearlier Liberal arguments. In his 1959book The Liberal Future, the Liberal leaderJo Grimond set out his understanding ofthe connection between liberty and prop-erty in remarkably similar terms to thoseused by Ackerman and Alstott:

‘The reasons which lead the Liberal Party tocampaign for the spread of ownership arepolitical and social as well as economic. Webelieve that the possession of some property isessential if a man is to enjoy full liberty [...]I am not saying that everyone who does nothave a house of his own or some savings is aslave. Nor am I equating the possession ofproperty with freedom. But a certain amountof elbow room: a certain cushion against eco-nomic setbacks such as unemployment, areessential to full liberty and can only be pos-sessed by those who are not totally dependenton the charity of the State or their weeklywage. The possession of some propertywidens a man’s choice and gives him morescope to exercise his talents. Personal owner-ship is the badge of a citizen as against aproletarian. It is a shield against petty tyran-ny.’ (Grimond 1959: 79)

If all are to be free, then it would seemthat all must have property; and theCTF is the first public policy to guaran-tee at least some property for all.

Liberal�Democrat�argumentsThe Liberal Democrats may have good ©

200

7 T

he A

utho

r. J

ourn

al c

ompi

latio

n ©

200

7 ip

pr

public�policy�research�–�March-May�2007 27

If�all�are�to�be�free,�then�itwould�seem�that�all�musthave�property;�and�the�CTFis�the�first�public�policy�toguarantee�at�least�someproperty�for�all

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 27

reasons that explain their opposition tothe CTF, notwithstanding their histori-cal and philosophical commitments. Letus now consider the reasons they give.

A frequent argument made byLiberal Democrats is that young peoplemight use their capital unwisely. Theymight spend their CTF on a holiday ora fast car. This is, in a way, an unusualobjection for a Liberal to make. IsLiberalism not about giving people –including young people – freedom andresponsibility? But putting this mischie-vous point aside, a second, substantialpoint is that the CTF policy can bedesigned in ways that promote respon-sible use. For example, it can be inte-grated with classes in financial literacyand the effective management of assets.A further point is that the mature CTFaccounts will typically include not onlymonies paid in by the state but moniespaid in by family and friends. This,too, can be expected to encourageresponsible use.

Finally, if one remains concerned,one can always consider placing condi-tions on how the account can be usedat 18 (conditions that might lapse later,perhaps at age 25), though the practicaldifficulties of this should not be under-estimated. In short, the problem ofresponsible use of CTFs is a genuineone, but one that can be addressed inthe design of the policy, and that hardlytells decisively against it.

The problem that some LiberalDemocrats have with the CTF, howev-er, is not that it gives people too muchfreedom, but that it gives them too lit-

tle. David Laws writes that ‘we shouldavoid giving people well-meaning gim-micks which they are obliged to use ina manner which the government thinksbest. The Child Trust Fund and freeTV licences are both examples of gov-ernment which thinks it knows best – itrarely does’ (Laws 2006: 161-162). Inother words, the CTF involves the stategiving parents money and telling themhow they must use it. The clear implica-tion is that the policy is paternalistic andobjectionable for this reason.

Paternalism means restricting the lib-erty of someone for their own good.So, if the CTF were aimed at enhanc-ing the welfare or freedom of parents,then Laws’s objection would have someforce. But, of course, it is not a policyaimed at parents. Strictly speaking, par-ents are not being given money by thestate. Newborn babies are being givenmoney by the state, and parents areserving as their trustees. The moniesare locked into the account, not in theparents’ interests, but in the child’s, toprevent parents spending what belongs,by right, to the child.

A comparison can be made withusing general taxation to fund free stateeducation. In principle, followingLaws’s logic, the tax money used tofinance free state education couldinstead just be distributed to parents tospend however they like. No sensiblecommunity would ever do this, becausechildren have a right to an education, aright that is not secured if parents are atliberty to use the funds that wouldfinance such an education to spend onforeign holidays and the like. The CTFworks on exactly the same principle:not the paternalistic principle of restrict-ing the freedom of parents for theirown good, but the impeccably Liberal(Millian) principle of restricting the lib-erty of parents for the good of theirchildren.

The main reason the LiberalDemocrats give for opposing the CTF,

public�policy�research�–�March-May�200728

© 2

007

The

Aut

hor.

Jou

rnal

com

pila

tion

© 2

007

ippr

The�main�reason�the�LiberalDemocrats�give�for�opposingthe�CTF�is�the�pragmatic�onethat�the�money�could�bebetter�spent

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 28

however, is the pragmatic one that themoney could be better spent. Theparty argues that the scarce publicmonies allocated to the CTF shouldinstead be used to finance programmesof early years intervention to help thepre-school development of children.They point to an impressive body ofevidence that pre-school programmes ofthis kind could be extremely effectivein tackling some of the deep-rootedcauses of deprivation.

As long as we accept that the policychoice we face is ‘CTF versus earlyyears programmes’, this argument isentirely persuasive. The fatal flaw inthe argument, however, is that there isabsolutely no reason why we shouldsee the policy choice we face as fixed inthis way. Consider the 2005 LiberalDemocrat General Election manifesto(Liberal Democrats 2005): the party’spledge to scrap the CTF and use thefunds instead for early years pro-grammes comes immediately after theparty’s pledge to scrap universitytuition fees.

So now we have at least three claimson the public purse: CTFs; early yearsprogrammes; and the scrapping of uni-versity tuition fees. Is scrapping tuitionfees better for social justice than theCTF? The advantage is by no meansclearly with the scrapping of tuitionfees. After all, the CTF is a universalpolicy that offers something for everyyoung person on maturity, not onlythose who have the sort of skills andinclination that make higher educationa realistic option.

The basic point can and should beexpanded. As things stand, theGovernment spends in aggregate verylarge sums on education (subsidisinghuman capital formation) and verylarge sums on subsidising asset accumu-lation, such as in the form of tax reliefsfor pension saving. However, in bothcases – human capital and financialcapital – we might question the way the

existing spend is distributed. As far as human capital is concerned,

we know that the earlier intervention is,the more effective it is. Yet, rather thanbeing concentrated in the early years,expenditures per child rise as childrenget older, reaching a peak for those inhigher education.

As far as financial capital is con-cerned, we know that about half of thetotal tax relief for private pension-sav-ing benefits people in the top decile ofthe income distribution (Agulnik andLe Grand 1998).

Against this background, in which itseems that all kinds of existing expendi-tures might be usefully redirected, itseems particularly arbitrary to pick onearly years spending and the CTF asthe two policies we must choosebetween. Both policies surely have agood claim to be financed out of theexisting aggregate spend on educationand asset accumulation, at the expenseof other policies that are less effective atdeveloping human capital or spreadingwealth.

ConclusionI do not mean to suggest that the CTFis a perfect policy, or that the LiberalDemocrats must endorse it in its pres-ent form, or indeed at all. For example,the concern that the Liberal DemocratMP Ed Davey has recently raisedabout possible inequality in matureCTF accounts, reflecting unequal fami-ly contributions into CTFs, is a validone.

Policy thinkers have begun to pro-pose ways of addressing this problem(for example, by requiring the state tomatch, pound for pound, family contri-butions into the accounts of children inlow-income households). But there iscertainly more thinking – and action –needed on this serious issue.

Indeed, it could be that there is somealternative universal asset policy to the ©

200

7 T

he A

utho

r. J

ourn

al c

ompi

latio

n ©

200

7 ip

pr

public�policy�research�–�March-May�2007 29

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 29

CTF that would arguably do a betterjob on balance of achieving its goals. Itwould be rash to rule this out. But,while there have been one or two hintsthat the Liberal Democrats mightexplore this possibility, the party has, asyet, offered not even the barest sketchof an alternative (Marshall 2004,Liberal Democrats 2006). And, if theparty were to take up a more construc-tive stance, this would demand achange in the party’s rhetoric. TheLiberal Democrats repeatedly label theCTF a ‘gimmick’, a term of abuse thathardly seems fair given the Liberal/SDP history of novel thinking in thisarea. Doubtless, some Tory or Labourwag of yesteryear would have con-demned proposals for North Sea Stock,SuperStock or the Citizens’ Unit Trustas gimmickry.

We come back, then, to the puzzle.Here is a policy, the CTF, that givesdirect expression to a deep, historicLiberal (and SDP) commitment to theideal of ‘ownership for all’. It is a policywith a forceful rationale in terms of lib-eral values. Contemporary philosophi-cal arguments for this type of policyecho uncannily the arguments thatleading Liberals like Jo Grimond oncemade for spreading wealth.

The Liberal Democrats have offeredreasons for their opposition to the poli-cy. But these reasons are extremelyweak. Indeed, they are so weak thatone suspects that they are mere ad hocrationalisations hastily cobbled togetherto defend a position that is not serious-ly thought out. At a time of risingwealth inequality, and widespread assetpoverty, the old Liberal slogan of ‘own-ership for all’ has never been more

urgent. So why do the LiberalDemocrats oppose the Child TrustFund?

Stuart White is Fellow and Lecturer in politicsat Jesus College, University of Oxford.

Note: web references correct February 2007

Ackerman B and Alstott A (1999) The StakeholderSociety New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

Agulnik P and Le Grand J (1998) ‘Tax Relief andPartnership Pensions’ Fiscal Studies 19: 403-428

Ashdown P (1989) Citizens’ Britain: A RadicalAgenda for the 1990s London: Fourth Estate

Brittan S and Riley B (1980) A People’s Stake inNorth Sea Oil: Unservile State Papers No.26London: Liberal Party Publication Department

Clouston D (1974) ‘Spreading Individual Wealth’,New Outlook 14 (9/10): 17-19

Dodds E (1957) ‘Liberty and Welfare’, in WatsonG (ed) (1957) The Unservile State: Essays in Libertyand Welfare London: Allen and Unwin: 13-26

Gravil R (ed) with Mennell S and Slavin M (1986)Equality and the Ownership Question London:Tawney Society

Grimond J (1959) The Liberal Future London: Faberand Faber

Laws D (2006) ‘Welfare Reform: FromDependency to Opportunity’ in Astle J, LawsD, Marshall P and Murray A (eds) (2006)Britain after Blair: A Liberal Agenda London:Profile: 144-162

Liberal Democrats (2005) The Real Alternative avail-able at: www.libdems.org.uk/party/policy/mani-festo.html

Liberal Democrats (2006) Poverty and Inequality,Federal Policy Consultation Paper 81, London:Liberal Democrats

Liberal Industrial Inquiry Committee (1928)Britain’s Industrial Future London: Ernest Benn

Liberal News (1958) (unsigned) ‘Liberals MEANOwnership for All’, Liberal News 640: 4, 11September

Liberal News (1959) ‘Revolutionary LiberalismPlans for the New Social Order’, Liberal News675: 1, 14 May

Marshall P (2004) ‘Introduction’ in Laws D andMarshall P (eds) The Orange Book: ReclaimingLiberalism London: Profile: 1-17

Owen D (1985) Ownership: The Way Forward:Open Forum Pamphlet No.9 London: SDPOpen Forum Committee

Watson G (ed) (1957) The Unservile State: Essays inLiberty and Welfare London: Allen and Unwin

public�policy�research�–�March-May�200730

© 2

007

The

Aut

hor.

Jou

rnal

com

pila

tion

© 2

007

ippr

ppr march 2007 3 gk:Layout 1 02/03/2007 10:56 Page 30