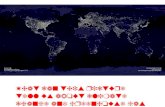

Whose Planet is it Anyway?

description

Transcript of Whose Planet is it Anyway?

Whose Planet is it Anyway?

Environmentalism and Science FictionPatrick D. Murphy

Department of EnglishUniversity of Central Florida

Proto-environmentalist works

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, or the New Prometheus

William Dean Howells, A Traveler from Altruria

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Herland

Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Rappacini’s Daughter” and “The Birth Mark”

H.G. Wells, War of the Worlds, “Food of the Gods”

Anti-environmentalist• Michael Crichton, State of Fear (2004)

• Walter Miller, Jr, A Canticle for Liebowitz (1959)

• Ian McDonald, Evolution's Shore (1995)

• Greg Bear Blood Music (1985)

Politically Overt• Kim Stanley Robinson, Science in

the Capitol Trilogy and Three Californias

• Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed and Always Coming Home

• Karen Traviss, The Wess-har Wars Series

Affect rather than Intent

Fictions can leave environmental or anti-

environmental impressions in readers' minds often more as

a result of the cultural and historical circumstances of their reception than as a

result of their conditions or intentions of production.

Definitions• Nature: the non-artificial or non-manufactured, material

reality that provides the setting for a work of sf. Kate Soper would refer to this definition as a "'lay' or 'surface' concept" as well as "a realist concept."

• This setting should not be perceived as external to the characters, since their natural physical makeup constitutes part of the non-artificial reality of the story.

• This recognition becomes particularly important in novels containing aliens. Not infrequently these representations of the Other as alien both reflect back on the representations of the Self as alien, and the defamiliarization of earthly animals as potentially anothers rather than others, thereby blurring the common nature-human divide.

Nature not external or opposed to culture and

technology• Culture and technology are designed and

manufactured with, and on the basis of, nature.

• Thus, a cyborg represents a melding of the natural and the technological, an artificial construct that does not occur spontaneously as the result of genetic evolution or sexual reproduction yet contains natural elements.

EnvironmentThe environment consists of the surroundings with and within which characters interact, but they themselves are usually represented as existing apart from that environment.

Let's limit the meaning of environment to the setting or locale surrounding characters that includes both the natural, the cultural, and the artificial. Much sf is set in manufactured environments and some in natural environments, including the human body.

Ecology• It is generally defined in two related ways, one in the

way that E. O Wilson defines it as a field of knowledge: "the scientific study of the interaction of organisms with their environment, including the physical environment and other organisms living in it.”

• Two, as an existence, i.e., a natural system that undergoes, or can undergo, both autodynamic change and externally induced change and encompasses multiple interactive environments (local ecosystems). This system includes actants considered to have agency, in the sense that we usually reserve for human beings.

• In the case of sf, agency may be limited to biological entities or only manifestations of sentient behavior, thereby potentially including artificial persons and intelligent machines.

What about Environmentalism

• In literary production there are at least three differentially focused types of environmentalism.

• The first, I would call nature-oriented: the literary work draws attention to particular aspects of a natural world. This world need not exist in the reality we know, but may be a thought experiment.

• Often these play a relatively minor role in the plot, which may be little more than a space western, as with the American tv series Firefly (2002). In other cases, the flora or fauna play an important role in the plot, but an entire ecosystem is not mapped out, as in Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars (1951).

Environmentalism II• The second form of environmentalism could be called

environmental writing, and more narrowly environmental justice writing. The author makes some kind of threat to an ecology or the planet the key to the plot and the response to it a major theme.

• In the 1950s writers produced a wide array of novels and movies in which the environmental dangers of nuclear power and unsupervised biological and chemical experimentation disrupt natural processes and produce monstrous creatures and geological threats. These movies focus on a specific type of environmental insult or sudden natural imbalance that threatens human existence.

• In film it is almost impossible to encompass the kind of detail needed for ecological environmentalism, and so viewers usually get agitational, single threat environmental justice pleas. Often the threat arises not from accident or oversight, but from the connivance of corrupt individuals .

Environmentalism III• The third form of environmentalism could be called ecological

writing. It tries to be systemic in scope, laying out an entire planet's biospheric activity, or educating readers about the interdependence of natural phenomena.

• While environmental writing can often be labeled as political in the sense of wanting, predicting, or demonstrating, a change in human social behavior, ecological writing is more likely to be viewed as ethical and philosophical, asking fundamental questions about humanity's place, potential, or future.

• Frequently the plots of these texts take readers only to the point where a decision must be made, as in Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka’s Nature's End (1986) or John Brunner's The Shockwave Rider (1975).

• In other cases they go further, as in the Mars trilogy of Kim Stanley Robinson (2004, 2005, 2007).

Bedlam Planet and the Sheep Look Up

• In the former, a group of Earth colonists attempt to settle a new planet without coming to terms with its ecology. Their efforts fail until they recognize themselves as the aliens who can become inhabitants only through submitting to this new ecology.

• "what sanity consists in is doing what the planet you live on will accept. And precisely because Asgard is not Earth, what is sane here may well seem crazy in earthly terms" (171). Brunner has given us an ecological novel, focused on ethics and philosophy that lead to a non-Earth-centered world view.

• The Sheep Look Up is a more narrowly focused environmentalist novel. It details numerous assaults on Earth's biosphere and argues about ethical behavior in terms of politics and policies rather than more fundamental concepts. The novel's focus encourages readers to take practical and immediate actions on any one of a number of fronts.

Post-apocalyptic scenarios

• Many nature-oriented sf novels set on Earth use a post-apocalyptic situation to argue for a return to nature.

• When virulently anti-technological they promote a neo-primitive way of life, as with Jean Hegland's Into the Forest (1996)

• The nature-oriented sf novel can encourage consideration of alternative structures for civilization, such as Ernest Callenbach's Ecotopia (1975) and Scott Russell Sanders' Terrarium (1985). The former focuses on how to live in a more nature-friendly way than it does on the potential ecological necessities for doing so and critiques the American consumerist lifestyle. Sanders indicates that people need to find their way back to an earlier nature-balance instinct in order "to build communities that are materially simple and spiritually complex, respectful of our places and of the creatures who share them with us" (283).

Girl in Landscape• Girl in Landscape (1998) by Jonathan Lethem opens with a heavily

polluted earth, but this setting serves less to thematize environmental crises as to advance the plot of the 13-year-old Pella's family's departure from Earth.

• This space western has three intertwined plots: Pella's interaction with other colonists and the planet's various species; conflicts between the educated tenderfoot newcomers and the established frontier mentality colonists; and conflicts between the colonists and the inhabitants. Girl can be seen to criticize both the recently arrived colonists and the already established ones in terms of the adults' inabilities to see the landscape and its native inhabitants intrinsically.

• Only the children seem able to develop new perceptual and conceptual paradigms in approaching the specific nature of their new home. They are nature-oriented precisely in the sense of trying to perceive this new reality in its uniqueness and show a potential for being remade into future inhabitants.

Environmental Novels Environmental novels are issue oriented

novels for which the crisis exists as the foreground of whatever extrapolation takes place

Invariably the crisis provides the basis for the plot, rather than merely the setting.

Sometimes these novels function primarily as cautionary tales that call on readers to change current behaviors to avert a catastrophe in the near future, such as nuclear disasters and wars.

Heat: Agitation and Propaganda

• Arthur Herzog's Heat (1977) presents the potential way that global warming might unfold. A dozen years before Bill McKibben published his nonfiction The End of Nature (1989), Herzog's protagonist, Dr. Pick, becomes concerned about the buildup of CO2 and a potential runaway greenhouse effect.

• As with Heat, hard sf usually shows a preference for a heroic, technological, or combination of the two, resolution that ends the crisis rather than the kind of open-endedness and ongoing process that ecological plot lines might suggest, or attention to the psychological-biophysical interactions that feminist sf often addresses.

Symbiosis or Competition

• Other sf novels treating environmental themes, however, downplay the agitational emphasis of Heat for more propagandistic and theoretical arguments. Noteworthy in these novels is an attention to symbiosis rather than competition in the human-nature interaction, and cooperation and adaptation rather than conflict in the human-human interactions.

• Many such works are set up to demonstrate a de-anthropocentric orientation that may even ascribe intrinsic value to wild nature or extol environmental resilience in contrast to the ephemerality of civilization.

George R. Stewart's Earth Abides

and Arthur C. Clarke's The

Sands of Mars.

Solaris• Stanislaw Lem's Solaris (1961; trans. 1970), is

also worth contrasting to Clarke's vision. In Solaris, Lem contends that all of the human research combined is insufficient to make sense of another planet's ecology and to determine whether or not its biosphere contains any kind of sentience. If read as an allegory about inhabitation of Earth, Lem's novel complements Stewart's recommendation of humility.

TechnophiliaWith Clarke and many other male writers of his generation, sf took on a decidedly technophilic attitude toward crisis aversion, space exploration, and human development.

But many contemporary sf writers, particularly women, have taken a different approach, emphasizing biology, biochemistry, ecology, genetics, and psychology, with frequent attention to ethics.

Amy ThomsonThe Color of Distance

Amy Thomson's The Color of Distance (1995) focuses on a human explorer marooned on another planet who can survive only because the primary sentient species, the Tendu, perform a biomolecular transformation of her body, including her immune system and skin. Thomson explores the very different approach these beings take to the biosphere they inhabit and how the protagonist must adjust not only her physical behavior but also her perceptions and ethics.

Through Alien EyesThe companion novel, Through Alien Eyes (1999) returns the protagonist to Earth with two aliens in tow. Readers then get to experience an ecological evaluation of Earth from their viewpoint. Perhaps most compelling in the second volume is the critique of white colonization and its destruction of indigenous lifestyles and peoples and how that represents a threat to sentient beings on other planets.

Joan SlonczewskiJoan Slonczewski's Elysium series includes Door into Ocean (1986), Daughter of Elysium (1993) The Children Star (1998), and Brain Plague (2000). Like many sf writers, Slonczewski has made a career as a scientist and is professor of biology at Kenyon. This background combines with a strong feminist commitment and a promotion of nonviolent political action.

Alien Societies: Mirror and Lamp

Societies on Elysium and Shora make use of genetic manipulation. While on Elysium technologism dominates to fulfill the single goal of extending human life, on Shora the manipulation is biological rather than technological, driven by the goal of adapting as much as possible to the planet's watery biosphere.

The plot of Door is not nearly as important as the society and the biomedical and ecological ethics these women develop. Slonczewski, like Thomson, recognizes that human beings alter their environments just as other animals do, and that they must do so in order to evolve in response to the changing ecologies of any planet. The issue is not the simplistic alter or don't alter Clarke posited, but rather the ecological dimensions of the alterations and the ethical requirements for sustainability and the preservation of all species.

Kim Stanely Robinson• Robinson's trilogy, Forty Signs of Rain (2004), Fifty

Degrees Below (2005), and Sixty Days and Counting (2007), presents a near future vision of abrupt climate change resulting from global warming.

• The first volume focuses on rising sea levels, the slowing of the North Atlantic current, and flooding of Washington, DC.

• The second focuses on sudden severe temperature swings, and

• The third focuses on scientific, economic, political, and personal responses to the changes.

• Clearly an example of agitational environmental literature, the trilogy reflects an interconnected world perspective about the global dimensions of the current climate change crisis.

Karen Traviss• Karen Traviss creates a far more affective tale of

ecological crisis and extreme remediation in her wess-har war series:

• City of Pearl [2004] • Crossing the Line [2004] • The World Before [2005] • Matriarch [2006] • Ally [2007]• Judge [2008]

Ecofeminist Orientation

Traviss's fiction embodies a strategic ecofeminist philosophy easily compared with Val Plumwood's arguments, particularly in Environmental Culture. Plumwood argues that "The ecological crisis requires from us a new kind of culture"

Like Le Guin's Anarresti in The Dispossessed, Traviss's Wess'har exemplify an ecologically responsible culture, with a low-impact agrarian life style backed by high-technology defenses. In addition to being matriarchal, they are also vegan, and display a daily commitment to sustainability.

What-if; If-then; A little Beyond