The Emergence of Abandoned Paddy Fields in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience · When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan...

Transcript of When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience · When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan...

Southeast Ast'an Studt'es, Vol. 29, No.2, September 1991

When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

Tsuyoshi KATO*

Introduction

Gullick, a noted Malaysianist, once

observed:

One picul of rubber was exported from

Negri Sembilan in 1902. This was an

event; it had never happened before.

[Gullick 1951: 38)1>

The first consignment of rubber from

N egeri Sembilan came from Linsum

Estate, located near the border of Seremban

and Port Dickson (Map 1). A few trees of

Hevea brasz"liensz's had been planted there

amongst the coffee in 1883, and a sample of

their latex was sent for evaluation to

Sungai Ujong, one of the major British

administrative centres in N egeri Sembilan,

in 1893 [Jackson 1968: 213, 215, 223].However, it was only in 1902 that the first

consignment of rubber was sent from the

Linsum Estate to England and sold for

a satisfactory profit. Thenceforth ensued

the successful expansion of rubber culti

vation in N egeri Sembilan.

The commercial cultivation of rubber,

not just In N egeri Sembilan but British

* 1JDli IMltl, The Center for Southeast AsianStudies, Kyoto University

1) Negri Sembilan is an old spelling of NegeriSembilan.

Malaya in general, was indeed an event.

There had been other cash crops, for

example, gambir and coffee, and other cash

generating enterprises such as tin-mining,

before the introduction of rubber. But

rubber decisively committed a large number

of Malay peasants in different parts of

Malaya to cash cropping and thus to

a money economy. Malay village life was

fundamentally affected by it.

The present paper will trace some of the

influences experienced by the Malay

peasantry through the expansion of rubber

cultivation. In order to do so I examine

the history of rubber cultivation in Negeri

Sembilan. The choice of Negeri Sembilan

for this inquiry is incidental; its results,

however, will hopefully be consequential in

their wider applicability to Peninsular

Malaysia.

There are good reasons for carrying out

the present investigation of rubber culti

vation. Unlike other cash crops which

preceded Hevea, rubber eventually spread

to various parts of Malaya. Moreover,

unlike other cash crops, rubber cultivation

turned out to be an enterprise of enduring

commitment, which has survived frequent

price fluctuations in the international rubber

market. Although oil palm has increased

in significance in recent years, rubber still

maintains an extremely important position

in the national as well as rural economy of

109

N

Melaka'(Malacca)

O~

Negerl Sembllan o 20 40 km

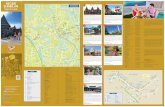

Map 1 Negeri Sembilan and Surrounding Areas (ca. 1988)

present-day Malaysia.

Malays were involved In rubber culti

vation almost from the beginning, although

the British colonial authorities did not

welcome this and sometimes even attempted

to discourage them. As Malay small

holdings multiplied throughout the 1910s

and 1920s, rubber cultivation began to

exert ramifying influences over various

aspects of Malay village life: land tenure,

settlement patterns, religious awareness,

110

material culture, rice cultivation, life styles

and work patterns. These are some of the

influences I will discuss in this paper.

The historical examination of Malay

smallholding provides valuable insights for

the understanding of contemporary rural

development in Malaysia. A significant

element of post-war development projects,

devised either by the colonial or Malaysian

governments, concerns the strengthening of

rubber smallholders, above all, Malay

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

smallholders. Concrete examples of this

are the Replanting Scheme (Rancangan

Tanam Semula), the FELDA (Federal

Land Development Authority) Scheme,

and the Fringe Area Alienation Scheme

(Rancangan Tanah Pinggir). These pro

jects are not implemented in a vacuum;

they are grafted onto the decades-long

history of rubber smallholding. The accu

mulated historical experience of smallhold

ing has affected the thought and behaviour

of the Malay peasantry. It is also bound

to affect the implementation and outcome

of development projects. The historical

examination of rubber smallholding IS

'\,:Jelebu~ ••,. l

\. •••'_•••--c........

"'1'" ; JempolSeremban l K I P'I h·-\··..,.. ) ua a I a ('

.... -. I./) /'I r' 1 ,J ••-._---,l\ "'-., ) ,/' ..It

Port Lr'i t. t"Dick;~n ,Rembaut·-----·

io 10 kilometers

Map 2 Administrative Districts and AdatDistricts (Luak) in Negeri Sembilan

Source: Peletz [1988: 17]; Nordin Selat [1976: V]

surely a prerequisite of our proper under

standing of Malaysia's contemporary rural

development.

Before going any further, let me briefly

describe my research methodology. The

present study comprises the second step in

my project to reconstruct a social history of

a luak or luhak [adat district] called Inas in

the District of Kuala Pilah, N egeri Sembilan

(Maps 1 and 2).2) In my previous writing

[Kato 1988], I described Malay village

life in Inas before the introduction of rubber.

In it I examined agricultural rituals

associated with rice cultivation and tried to

understand the cultural meaning of rice

cultivation, an economic activity of decisive

importance before rubber was introduced

into Malay villages in the late 1900s. The

present study begins where the previous

study ended, and covers the period up to the

early 1940s. 3)

I utilize four major sources of information

in the reconstruction of local social history.

2) Concerning my reasons for choosing Inas asa research site, refer to Kato [1988: 111-112].

3) There are at least four more studies plannedafter the present one. In a chronological order,the first one will deal with the Japanese occupation and the Emergency when the administrative reorganization and political transforma·tion of rural society proceeded from above.The second focuses on the 1960s when thepoliticians, at the expense of administrators,wielded increasingly stronger influence over thedecision-making processes of rural development.The third study concerns the last twenty yearswhen the industrialization, urbanization andpoliticization of Malaysian society in general,

under the New Economic Policy, has engulfedInas. Fourthly "Inas at the crossroads" willpull together different strands of observationand consider future prospects for the Malayvillage.

111

One is my field research conducted in Inas.

I spent the total of five months in Negeri

Sembilan between late 1986 and early 1989,

of which close to four months were spent in

Inas. While in Negeri Sembilan, I also

collected relevant data at various govern

ment offices at Kuala Pilah and Seremban.

In writing this paper, land registration

records at the Land Office of Kuala Pilah

proved to be very useful. In addition to

field work in Negeri Sembilan, I spent

about one month at the National Archives of

Malaysia, mainly reading Negri Sembilan

Administration Reports and Annual Re

ports of Kuala Pilah District from the

colonial period. The National Archives

unfortunately does not have complete sets of

these documents. Nevertheless, some of

the documents I could locate there were

useful for my present purposes. Finally,

I consulted various published materials on

Malay society and rubber cultivation in

Malaya.

Among the four sources, I mainly relied

on the latter three in writing this paper

which is primarily a general description of

the history of rubber cultivation in Negeri

Sembilan. The paper is organized ac

cording to the following topics:

I Negeri Sembilan in the Nineteenth

Century

II Chinese Cassava Estates

III British Colonial Rule and Land

Legislation

IV Establishment of Pekan (Market

Towns)

V Introduction of Cultivated Rubber

to Malaya

VI History of Rubber Smallholding in

112

Mukim Johol

VII Implications of Rubber Small-

holding

VIII Changes in Material Culture

IX Rice and Rubber

X Diminishing Forest and Agricul-

tural Rituals

As a concluding remark, the "Anatomy of

Malay Smallholding and Rubber Tapping"

is discussed.

I Negeri Sembilan in the NineteenthCentury

Situated relatively inland, the cultural

core areas of Negeri Sembilan, that is,

Jelebu, Rembau, Sungai Ujong, Johol, and

Sri Menanti, are seldom mentioned in

European writings before the nineteenth

century. Thus the following discussion

basically concerns conditions in N egeri

Sembilan in the nineteenth century, espe

cially in the latter half of the nineteenth

century.

Before the introduction of rubber, the

mainstay of the Malays of Negeri Sembilan

was rice cultivation. The quantity of rice

harvested largely determined the quality

of life enjoyed. Because of the long

maturation period of indigenous varieties of

rice, the Malays were involved in rice culti

vation, though admittedly not continuously,

for probably nine to ten months of the year

[Kato 1988: 128J. Various stages of rice

cultivation entailed agricultural rituals and

festive activities. The annual cycle of rice

cultivation accentuated a basic rhythm of

village life. Rice cultivation was central to

economic life, ritual life, and the belief

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

system of the Malay villagers.

Despite the overwhelming importance of

rice cultivation, it was not the only economic

pursuit in N egeri Sembilan in the nineteenth

century [Gullick 1951]. Vegetables were

planted in kampong (homesteads), and

edible plants were collected from around

sawah (wet-rice fields) and forest. The

extraction of forest products such as rattan,

honey, beeswax, gaharu (incense wood),

all sorts of forest rubber, and damar (resin)

was important because of their monetary

value. Fishing was carried out in the

sawah, ponds and rivers as fish were the

primary source of animal protein. The

raising of cattle and poultry was common,

for they were "live assets" which could be

multiplied or, if need be, exchanged for

money or other goods or even used to

generate prestige through their conspicuous

consumption at ceremonial occaSIOns.

Pottery-making, atap-making (making

thatch out of palm leaves) and mat-weaving

were also carried out but these products

were probably more for self-consumption

than for markets, at least until the early

nineteenth century. (On the other hand,

after the mid-nineteenth century, Malay

handicrafts had to compete against Chinese

handicrafts.) Some cash crops, such as

coffee and tobacco, began to be cultivated

towards the last quarter of the nineteenth

century. Tin-mining was practised in some

parts of N egeri Sembilan, for instance at

Sungai Ujong, Jelebu and Gemencheh but

was already being dominated by the Chinese

from around the middle of the nineteenth

century. Gold-mining was not so im

portant as tin-mining.

Despite this wide range of economIC

pursuits existing in Negeri Sembilan, the

general impression is that Malay village

life, relatively speaking, was still on the

periphery of the money economy in the

first half of the nineteenth century. As

late as 1890, Javanese who came to Jelebu

(a tin-producing yet admittedly remote area

in N egeri Sembilan) are said to have com

mented that "the people of Jelebu so long as

they have food are content." This implies

that the Malays of J elebu had not yet

developed new needs and wants normally

instigated by a money economy [Hill 1977 :

138].

The above situation began to change from

around the middle of the nineteenth century.

Thriving Malacca, which became a British

possession in 1824 and later functioned as

one of the major entry points for massive

Chinese immigration for tin-mining, was an

important factor in this development.

Malacca and the Chinese tin-mining areas

in inland N egeri Sembilan came to con

stitute enclaves of a strongly money

oriented economy In contrast to the

prevalence of village economies based

largely on self-sufficiency.

Some Malays In Negeri Sembilan

developed a steady involvement with the

money economy through their interaction

with these Chinese enclaves. In the 1830s

the people of Johol, Sri Menanti, and

Rembau were exporting surplus rice to

Malacca. Farm produce and livestock

were sold to the Chinese in tin-mines in

Sungai Ujong, Jelebu, Malacca, and later

Kuala Lumpur. Malacca Chinese came

to the Kuala Pilah area to buy fruit in the

113

1880s. Some Malays squatted near

Chinese tin-mines in the 1880s. Women

. re-panned and re-washed refuse heaps of

sand for tin which Chinese miners had

already panned and washed, while men did

odd jobs around the mines such as building

sheds [Hill 1977: 126, 137; Winstedt 1950:

124; Rathborne 1984: 132-133,309,319].

The involvement of the Malay peasantry

in the money economy was given a further

impetus in the last quarter of the nineteenth

century. Two events were responsible for

this. One was the expansion of Chinese

cassava estates from Malacca to Negeri

Sembilan; the other, the consolidation of

British control over Negeri Sembilan in

1887. One underlying element in these

events was the restoration of "order" in

Negeri Sembilan. The advent of large

revenues for Malay rulers through tin

mining concessions and the influx of many

Chinese to the tin-mines caused frequent

feuds and much warfare among various

Malay leaders and also among rival Chinese

groups. The restoration of "order" by the

British in the last quarter of the nineteenth

century was conducive to the expansion of

cassava estates in practically all of Negeri

Sembilan.

Both events mentioned above were es

pecially important to Inas. Inas, being

geographically isolated from the major

riverine trade routes and having no nearby

tin-mines, had been little involved in the

money economy even after the mid

nineteenth century. However, this situ

ation began to change in the last quarter of

the century. As Inas is situated relatively

near Malacca, the expansion of the Chinese

114

cassava estates, with the concomitant

development of land transportation, proba

bly reached it by the latter half of the 1880s.

Concurrently, the establishment of British

control entailed the imposition of "house

taxes" in Inas, apparently from around 1888.

The implementation of the "house tax"

system presupposed a certain degree of diffu

sion of the money economy and simultane

ously predestined its further penetration.

II Chinese Cassava Estates

Cassava is significant as a cash crop as

it is a source of tapioca flour, flakes or

pearls. It is not clear why the demand for

tapioca increased in the nineteenth century.

There are two possible, though still con

jectural, reasons for this: the rising demand

for laundry starch in the British cotton

industry and/or for tapioca pudding in step

with the increasing consumption of coffee,

tea and sugar in Europe. In either case,

another important factor in making tapioca

a successful export product must have been

the opening of the Suez canal in 1869 and

the subsequent adoption of steamships for

the Asia-European sea route. The result

ing decline in transportation costs benefited,

for example, the export of sago, a bulk

commodity, from the Straits Settlements

to Europe [Latham 1978J; the same could

well apply to tapioca.

Cassava estates in Malaya were initiated

and subsequently controlled mainly by the

Chinese of Malacca. 4 ) The large-scale

4) The following account of the development ofcassava estates in Negeri Sembilan is based onJackson [1968: Chapter 4].

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

commercial cultivation of cassava began in

Malacca in the early 1850s. Its processed

product, tapioca, was mainly exported to

the British market. As lands in Malacca

became exhausted, the cultivation of

cassava eventually spread to neighbouring

Negeri Sembilan and, to some extent, to

Johor. But it never became significant in

other states of British Malaya.

Cassava estates were operated on a

system of shifting cultivation. This culti

vation method was extremely wasteful and

devastating to the soil. A cassava estate

concession might occupy an area from

1,500 to 5,000 acres. A lot ofland operated

at anyone time might range from 100 to

1,000 acres. Newly opened land was

cultivated for from three to five years,

during which time two or three crops of

cassava were harvested, with diminishing

monetary return. Then the lot was

abandoned and a new tract of forest in the

conceSSIOn was opened up. When the

concession was exhausted, a new one was

acquired. In processing cassava roots to

tapioca, large supplies of firewood were

required. This fact also accelerated the

speed of cultivation shifting and the de

nuding of forest. Thus, the cassava estates

steadily shifted towards the outer areas of

Malacca and, in due course, far beyond.

The expansion of cassava estates reached

a peak in Malacca in 1882, by which time

the frontier of cassava cultivation had

already advanced to the border areas be

tween Malacca and Negeri Sembilan.

Cassava cultivation in N egeri Sembilan

started in the latter half of the 1870s,

initially in the Sungai Ujong area. Later

on, in the early 1880s, before tapioca prices

plunged in 1882, it spread to Rembau, the

neighbouring area of Malacca and Sungai

Ujong. By the latter half of the 1880s,

particularly after tapioca prices began to

recover in 1886, cassava cultivation was

also well established in Tampin, J ohol,

and Gemencheh, with all conceSSlOns

situated near Malacca and along the

Malacca-Tampin-Kuala Pilah road. In

the meantime, Sungai Ujong ceased to be

important in the cultivation of this crop.

Cassava remained the single most

important cash crop in the present districts

of Rembau, Tampin and Kuala Pilah until

the end of the first decade of the twentieth

century. By that time much forest in the

areas was denuded, the colonial govern

ment's attitude toward cassava cultivation

became negative, and the gospel of a new

cash crop, rubber, was already on the

horizon.

Changes brought about by the spread of

cassava estates were manifold. Road

networks were opened, improved and

expanded in order to connect Malacca and

the areas of tapioca production. Cart

roads crisscrossed and checkered the

countryside, because cassava estates and

forests for firewood supplies had to be

connected by a road to the tapioca factories.

The latter were usually located near a river

as the processing of cassava roots required

water for washing. Bullock carts eventually

became ubiquitous as a means of trans

portation. Thus was initiated the "age of

land transportation" in N egeri Sembilan.

The incorporation of Negeri Sembilan in

the British sphere of influence in 1887

115

further encouraged the advance of land

transportation.

Another change wrought by the spread

of cassava estates was the closer level of

encounters between Malays and Chinese.

Malay villagers in general had relatively

limited associations with the Chinese when

the latter were mainly concentrated in the

tin-mines. Because of the shifting nature

of cassava cultivation, the estates, unlike

the encapsulated enclaves of Chinese tin

mines, spread to almost all corners of

Malacca and Negeri Sembilan. Tin-mines

were isolated dots on a map, while cassava

estates comprised a horizontal expansion.

Bustling activities associated with cassava

cultivation and processing were more visible

to the outsiders than tin-mining activities.

Tapioca factories were usually established

near water sources and at the same time

close to existing or newly-established road

systems. Bullock carts busied themselves

shuttling between the factories and cassava

estates.

The above characteristics of the tapioca

industry must have made the Chinese more

familiar figures in the countryside of Negeri

Sembilan than before. Closer encounters

between Malays and Chinese in rural Negeri

Sembilan are shown in the "racial incidents"

which were sometimes reported in official

documents towards the end of the nineteenth

century. Such incidents include "mar

riages" between Malay women and

Chinese men and alleged murders of

Chinese by Malays.S)

5) In the early 1890s the Kathi (Islamic official) ofJ ohol complained to the District Officer ofKuala Pilah that two Inas women and one Johol

116

Although Malays were not directly in

volved in the commercial cultivation of

cassava, many of them were hired as wage

labourers on the estates. They felled trees

at the initial stage of opening up the forest,

and, after the planted lot began yielding,

they dug cassava roots, loaded them onto

bullock carts and carried them to the

tapioca factory. This kind of arrangementwas common because it was not unusual for

estates and tapioca factories to be located

near Malay settlements or even in the

midst of them. 6) Thus cassava estates

provided Malays with relatively easy access

to a cash income.

In many ways, the expansion of the

woman had married Chinese men. In the opinion of the District Officer, the Malay womenwere probably concubines of the Chinese(NSSF 568/92). According to the journalfor January 1891 by the District Officer of KualaPilah, a Chinese was murdered in KampongNuri in the previous year and two Malays weresuspected of having committed the crime (NSSF174/91). The identification numbers in parentheses signify document numbers used forthe Negri Sembilan Secretariat Files at theNational Archives of Malaysia. All abbreviations for documents cited in this paper are listedin the Bibliography.

6) For example, there was a large cassava estate(the present Sungai Inas Estate) just to thesouth of Inas, and its factory was located inKampong Seginyeh, at the confluence of twosmall rivers flowing through Inas. Accordingto Inas residents who are in their seventies orabove, in their childhood some villagers stillworked on the cassava estate for wages. Beforethe 1920s the path connecting Inas to PekanJohol, a nearby market town, was through thecassava estate. Villagers sometimes encountered pigs raised by Chinese along the path tothe pekan (market). Cassava cultivation wasoften coupled with pig-rearing because pigscould be fed the refuse from tapioca processingUackson 1968: 55].

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

cassava estates and the resultant changes

foretold what Malay society in N egeri

Sembilan would later experience as rubber

cultivation expanded. For Malay peasants

it provided a foretaste of their society's

irrevocable transition from a subsistence

oriented economy to a money economy.

III British Colonial Rule and LandLegislation

Perak, Selangor and part of Negeri

Sembilan, that is, Sungai Ujong, came

under the sphere of British colonial rule in

1874. The rest of Negeri Sembilan fol

lowed in 1887, together with Pahang. These

four states (Perak, Selangor, Negeri

Sembilan and Pahang) were to become the

Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896.

The establishment of colonial rule brought

about many changes in the Malay society

of Negeri Sembilan, especially concerning

land. The British began registering land

for revenue purposes. The first state-wide

land registers in N egeri Sembilan are called

the Malay Grants. The Land Office of

Kuala Pilah still preserves the district's

Malay Grants in its office. I was fortu

nately able to examine the grants of Mukim

Johol in which Inas is located. Altogether

there are nine books of Malay Grants for

this mukim (subdistrict), containing some

eight hundred entries. The first entry in

the first book is dated November 17th,

1887 and the last entry in the last book

October 25th, 1896.

As far as I can ascertain from the case of

Mukim Johol, the Malay Grants are

considerably different in character from the

Mukim Register, which eventually replaced

the Malay Grants. The Grants are written

in Jawi (Arabic letters), and entries are

made according to household, not according

to land lot. Thus one usually sees both

sawah and kampong (homestead) registered

under one entry. No specification of land

size is made. 7 ) No land other than sawah

and kampong is registered in the Malay

Grants, which suggests a rather narrow

range of land utilization patterns among

the Malays of this period. Orchards

(dusun) , for example, might have existed

then but they were probably not yet so

economically important, at least not

important enough to be considered for tax

purposes.

It is clear that the objective of the British

in compiling the Malay Grants was to tax

households rather than land lots. They

7) Sawah and kampong in the Malay Grants werelater to be classified in the Mukim Register as"customary land" or land regulated accordingto matrilineal ada! (a body of social etiquettes,customs and tradition). However, some entriesfor these lands were made under male namesin the Malay Grants, which may suggest "confusion" in the translation of matrilineal adatinto the Malay Grants. (Dnfortunately Ifailed to check the relationship between these"land-possessing" males and the women underwhose names the lands were eventually to beregistered in the" Mukim Register. Althoughit is probably impossible to check this, it wouldbe valuable to ascertain whether the men werehusbands or maternal uncles to the landinheriting women. The importance of thisdistinction was suggested to me by MichaelPeletz. Also see Peletz [1988: 137-138].)I observed no similar confusion in the M ukimRegister. Jinjang was sometimes used asa measurement of sawah in the Malay Grants.It refers only to the width of the "head" ofsawah and does not specify its size.

117

probably started collecting "house tax"

around 1888. A letter from the Super

intendant of Police at Kuala Pilah, dated

January 4th of 1888, addressed to the

Colonial Secretary, reports that Datuk

Penghulu Inas (adat chief of Inas) , after

some negotiations, finally agreed to collect

"house tax," that is, one dollar per house,

for the British: "He [Datuk Penghulu

Inas] has now accepted his allowances tho'

he has asked for certain small additions &

he & his chiefs have also agreed to the

collection of the House tax in Inas."

Initial negotiations between the two sides

took place in April of 1887. The final

agreement stipulated that the number of

adat leaders in Inas who were to receive

monthly allowances from the British would

be increased from nine to seventeen. 8)

Over and above the lengthy negotiations

required and other difficulties they must

have encountered, the British, from the

beginning, were evidently not happy with

the house tax. At the first meeting of the

Negri Sembilan State Council, held on

December 9th of 1889, they already

proposed an alternative to the house tax:

the flat rate of one dollar per "holding"

was to be replaced with a five-percent tax

on the average padi yield of sawah under

cultivation (NS AR 1889, pp. 3-4).

Gullick [1951: 42] writes: "During the

1890's the tax was changed to an assessment

upon the profitability of the land (50/0 of

the annual crop of padi instead of $1 per

8) See File "K.P. 9/88" in the Files "Super"intendant of Police, Kuala Pilah, NegriSembilan 1887-1888" at the National Archivesof Malaysia.

118

acre) and it was collected by District

Officers." However, I could find no indi

cation that the proposed new tax was actu

ally implemented in Mukim J ohol. 9)

I t is often stated that land possessed no

monetary value before the establishment of

British colonial rule in Malaya. Swetten

ham, who had long experience in British

Malaya, observes: "Land had no value in

the Malay States of 1874 and it was the

custom for anyone to settle where he

pleased on unoccupied and unclaimed

land" (quoted by Gullick [1958: 113, n. 2]).

Judging from the way the Malay Grants

were organized, apparently the British did

not yet anticipate the commoditization of

Malay smallholdings when they started

compiling the Malay Grants in 1887. The

9) In Mukim J ohol one dollar per "holding" wasevidently still being collected through lembaga(matri-clan heads) in 1893. In a documentdated March 16th of 1893 were listed 164 housesunder seven lembaga in Inas, 432 houses undernine lembaga in Johol, and 213 houses undersix lembaga in Gemencheh, with annual allowances totalling $648 for 22 lembaga inMukim Johol (NSSF 380/93). The documentis titled "List of holdings under the jurisdictionof each Lembagas of Inas and Johol." It liststhe names of lembaga in Inas, Johol, andGemencheh, the number of "rumah" (house)under their jurisdiction, and the amount oftheir monthly allowances. It is clear that"holding" here means house or household, notland holding. (Note that in the above quotation Gullick seems to equate house tax with$1 tax per one acre holding.) Likewise, thefinal entry in the final book of the Malay Grantsof Mukim Johol, registered on October 25th1896, still shows an entry "cukai [tax] $1.00"in red ink on its backpage, indicating that thehouse tax was still being levied on that date.Malay Grants contain no information (forinstance, sawah size) which could be used forthe implementation of the newly proposed taxsystem.

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri SembiIan Experience

Malay Grants for Mukim J ohol are listed in

books of two different sizes: one with the

lengths of 30 em by 19 em and the other

with the lengths of 22 em by 15 em. In

formation was filled on one page per

holding/house with its backpage blank.

Each page contains the following informa

tion: name [of the head of the holding],

tribe (or clan name of the holding head),

lembaga [of the holding head], number of

persons [in the holding], nature of culti

vation (that is, sawah and/or kampong),

and date [of registration]. The page size

of the Malay Grants allows no room for

writing any other information, for instance,

on subsequent land transactions. In ad

dition to this size limitation, the fact that

entries in the book were made according to

a house, not according to a lot, without

specifying land size, meant that the Malay

Grants would not be useful once the

commoditization process of Malay small

holdings unfolded.

In establishing and extending control in

Malaya from the 1870s to the 1890s, it

became imperative for the British to devise

a relatively uniform system of land legis

lation in the western Malay States which

would allow the expansion of British and

other European-managed estates. We

should note here that these were the

decades when European interests In

plantation agriculture, for example, sugar

and coffee, were growing in Malaya

[Jackson 1968: Part II]. The person who

most influenced the drafting of this legis

lation was William Maxwell.

In 1882, Maxwell, a British official

familiar with Malay systems of land tenure,

was sent to Australia to study the Torrens

System of Registration of Title. The

Torrens System was initially introduced in

South Australia in the 1850s. Kratoska

[1985: 25] succinctly summarizes its charac

teristics: "The Torrens System, which

employs title by registration rather than

title by deed, is based on land registers

maintained by the government. All alien

ated land is entered in the registers, and

these entries are the land titles; to be

legally binding, mortgages, leases, and

transmissions of title must also be entered in

the register."

Maxwell was appointed as the Resident

of Selangor in 1889. He drafted the

Selangor Land Enactment of 1891, basing

it on the Torrens System. This law laid

the foundation for land enactments which

were passed, without much variation, in

each of the Federated Malay States in 1897;

it was later repealed and reenacted with

revisions in 1903. In the 1897 enactments,

tenure of smallholdings came to be referred

to as tenure by entry in the Mukim Register

[ibid.: 24-26; Allen and Donnithorne 1954:

115J. This comprised the first tangible

step toward the replacement of the Malay

Grants with the Mukim Register. In

Negeri Sembilan, the initial registration

and survey of land for the implementation

of the enactment continued until 1904

[Gullick 1951: 42].

I examined the Mukim Register of

Mukim J ohol in the Land Office of Kuala

Pilah. There are altogether 33 books in the

Register for this mukim. The first entry of

the first book is dated June 23rd of 1903.

Reflecting the purpose of the Mukim

119

Register, the books are designed to record

all land transactions revolving around the

entry of a particular lot. Thus the book

size of the Mukim Register is considerably

larger than that of the Malay Grants, with

dimensions of 49 em by 30 em. Moreover,

two open pages are used for one entry.

The Mukim Register concerns small

holdings of less than ten acres. They

'record the holdings of Malays, Chinese and

Indians but most of the entries belong to

the Malays. Each entry in the Register

includes the following information: number

of the holding (or a sort of identification

number in the Mukim Register), survey

number, number and nature of former title

[if any], name of owner, area (that is, size),

boundaries, nature of cultivation (for

example, sawah, kampong or rubber) and

locality (that is, settlement or village name),

special conditions [of cultivation, such as

"no rubber"], subsequent proceedings (date

of issuance of extract and so on), [amount

of] annual rent, and remarks (such as

"customary land").

I t is interesting to note that initially two

facing pages of the Mukim Register

contained two entries, one occupying the

top half and the other the bottom half.

This changed in early 1905 when the whole

two pages were alloted to a single entry.

As will be described later, this coincided

with the first rubber planting boom in the

European estate sector. This change in

the allocation of page space in the Mukim

Register may reflect an awareness on the

British side that land transactions among

Malay smallholders would become more

frequent in the future.

120

If the British most probably devised

the Mukim Register in full anticipation

that Malay smallholdings would be com

moditized, the very existence of the Register

in turn promoted the commoditization

process. Land began to be registered

under individual names; the procedure for

alienation was clearly specified; the transfer

of ownership was regulated and guaranteed

legally. These characteristics of the Regis

ter all contributed to the rapid commodi

tization of land. As will be discussed later,

Malay peasants were already speculating inopening up and selling smallholdings during

the 1905-1908 rubber planting boom. In

retrospect it is the Mukim Register, among

other things, which bred and nurtured

Malay attachment to land ownership,

although not necessarily to the land itself.

IV Establishment of Pekan

(Market Towns)

The last quarter of the nineteenth

century was a time of great transformation

in Negeri Sembilan. The general atmo

sphere was replete with new experiences

and new expectations. Malay peasants

increasingly came into contact with un

familiar peoples and institutions in their

own environment. As a result of the

expansion of the cassava estates, more and

more Chinese were seen in the Malay

countryside. Some of them were operating

as merchants among the Malay villagers in

the 1890s [Gullick 1951: 53]. An in

creasing number of Sumatran Malays came

to the peninsula, including Negeri

Sembilan, as agricultural pioneers, mer-

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

chants or estate workers [Hill 1977: 127;

Kratoska 1985: 17; Gullick 1951: 52

53]. Malays, who may initially have been

"unable to suppress their wonders at the

whiteness of a European skin, and astonish

ment at being able to see the veins in it"

became accustomed to the sight of European

planters and colonial officials, and even to

Sikh police. 10) After the consolidation of

British rule, such hitherto unknown insti

tutions as police stations, and later

vernacular schools, were established. The

expansion and improvement of road

systems further stimulated the movement of

peoples, commodities, and ideas.

In particular, transformations during this

period meant that Malay peasants were

increasingly drawn into the money economy.

For one thing, each house under the Malay

Grants had to pay an annual house tax of

one dollar to the colonial government.

There were more and more opportunities

for wage labour available, for example,

forest clearing at European coffee estates or

road construction sites [Rathborne 1984:

50,331-332; Hill 1977: 138]. As already

mentioned, a large number of Malays were

also hired in the tapioca industry as

labourers or drivers of bullock carts (see

also Rathborne [1984: 37] and Jackson

[1968 : 74]). Circular migration was

becoming common. Though referring to

Malacca in the early 1880s, Rathborne

[1984: 34] makes the following observation

10) The quotation is from Rathbome [1984: 193].It describes the reaction of Malays in Perakwhen they saw a white man (Rathbome) for thefirst time, probably in the late 1880s. A similarreaction possibly occured among the Malays ofNegeri Sembilan.

concerning circular migration:

Malay silversmiths, blacksmiths, and

carpenters are fast being superseded by

Chinese, and as the villagers have no

trades to give them occupation during the

time there is nothing doing in the fields,

many of the men leave their homes in

search of employment, returning at

frequent intervals, for they are able by

working three months in the year to

supply themselves with all the necessaries

they require for the remaining nine.

At the hub of these transformations and

commotions were the pekan or market

towns. New institutions such as police

stations, vernacular schools, dispensaries,

and later offices for penghulu (mukim

officials) were usually established In

pekan. ll) Chinese, Indians, Europeans,

and Malays congregated there. Pekan

were the nodal points of transportation

systems, through which money, peoples,

commodities, and ideas circulated. At

shops and stalls in pekan the Malays were

introduced to soap, matches, kerosene oil,

and firecrackers. At coffee shops and small

restaurants they also came to know the

habit of tea- or coffee-drinking and acquired

a taste for Chinese noodles and Indian

11) Evidently there were variations as to when thepenghulu were instituted in different districts ofNegeri Sembilan. There were no penghuluyet in Kuala Pilah in 1916, while there werealready appointees in Jelebu in 1910. In thelatter district land applications began to bemade through penghulu, not through lembaga,after 1910 (AR KP 1916, p. 7; AR JB 1910,p.11).

121

roti canai (Indian "pancake").

I do not know the history of pekan in

Negeri Sembilan. Old pekan were usually

established at the major confluences and

kuala (river mouths) of relatively heavily

trafficked rivers. Yet, judging from the

fact that the modern pekan in Malay

society were, and still are, primarily

inhabited by Chinese (and in some cases by

Indians), the growth of contemporary pekan

must date back to the time when the Chinese

started taking up residence in inland Negeri

Sembilan. The development of roads was

another important factor, as these pekan

are located along trunk roads.

As already mentioned, tapioca factories

were connected with Malacca via cart roads

or metalled roads. The transportation of

goods between these places was two-way.

Bullock carts brought tapioca to Malacca

and carried back factory provisions on their

return trip [Jackson 1968 : 72-73] . As

pekan were established, it is probable that

these bullock carts also began to transport

from Malacca goods for sale at the pekan.

In the meantime, pekan functioned as

collection points of forest products such as

rattan and damar. According to a man in

his late seventies in Inas, in his childhood,

he used to accompany his father in carrying

rattan or damar from the village to Pekan

Johol, the pekan nearest to Inas. Given

these developments, the transportation of

goods by bullock cart became a business in

itself.

Pekan J ohol was already in existence

around 1890, complete with police station

and shops (NSSF 966/92). One of the

shops was probably an opium shop supply-

122

ing to the Chinese cassava estates.12) As

early as 1892 a certain W.H.I. Silva pro

posed to the British Resident of Negeri

Sembilan that, if given government

assistance, he would be willing to run a daily

mail coach between Malacca and Kuala

Pilah via Tampin and Pekan J ohol in ten

hours (NSSF 553/92). The proposal

indicates the existence of a good road system

as well as frequent contacts and communi

cations along this route. The first ver

nacular school in the area was being

constructed in Pekan J ohol in 1898 [NSSF

3036/98].

In essence the pekan were the embodi

ment of the money economy. It was at

the pekan that money and goods could be

exchanged and unfamiliar and attractive

commodities could be purchased for a

price. There had already been increasing

opportunities to earn cash before the

establishment of colonial rule, for instance,

carrying out odd jobs around Chinese tin

mines and working for wages at cassava

estates; these were all significant for the

expansion of a money economy. But far

more important than this was the fact that

the pekan, together with the itinerant

Chinese merchants who carried goods on

a pole and travelled between the pekan and

Malay villages, constituted institutionalized

agents of consumption goods and thus

aroused new material wants in the hearts

of Malay peasants.

Rathborne, who opened a coffee estate at

12) It is not clear when the first opium shop was builtbut there was an application by a Chinese toopen the second opium shop in Pekan Johol in1893 (NSSF 463/93).

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

Gunung [Mt.] Berembun, near the border

between Kuala Pilah and Seremban (Map

1), in the early 1880s, makes the following

observation about his Malay workers, most

of whom must have come from N egeri

Sembilan:

I always entertained them [Malay

workers] to tea, and their wonder was

at the clock, whose pendulum swung

backwards and forwards with constant

regularity; and the ticking of my watch

would surprise and amuse them as they

placed it to their ears. Photographs

they did not seem to understand at all,

. . . . Notwithstanding the strangeness of

their surroundings they never appeared

gauche or awkward except when sitting

on a chair for the first time, and then

they would sit gingerly on the very edge

of the seat, and were apparently half

afraid lest it should give way beneath

their weight. [Rathborne 1984: 53]

Malay naivete about European material

culture was to undergo a rapid change.

Curious products which Rathborne showed

to his Malay workers soon ceased to be

objects of mere novelty and became objects

of craving. In 1896, reviewing the first

ten years of British rule in N egeri Sembilan,

Cazalas, the acting District Officer of

Kuala Pilah, made the following remark:

Ten years experience of the people

here have demonstrated that

weakness for fine cloths and for adorning

themselves with gold and silver orna

ments has increased in proportion as

facilities for procuring money has [sic]

advanced a fondness for tweed

suits, felt caps, smoking caps and even

the 'sola topi' has been creating [sic].

(quoted by Hill [1977: 138])

Through their exposure to the pekan, the

Malay peasantry of Negeri Sembilan was

immutably enticed into a journey toward

the money economy, a journey with no

return.

V Introduction of Cultivated

Rubber to Malaya

Concerned about the presumably Im

pending depletion of tin deposits in western

Malay States, Rathborne [1984: 153] wrote

as follows in the late 1890s:

. . . these alluvial deposits are now

within measurable distance of being

exhausted along the western coast; and

then the mining population will have to

turn their attention to the undeveloped

eastern side of the mountain. Before

this takes place it is to be hoped that the

permanent cultivation of some agri

cultural products will have extended suf

ficiently to enable this certain loss of

revenue to be in some measure recouped,

and that the nomadic habits of a con

siderable proportion of the Malay settlers

will not cause them to abandon their

holdings and migrate elsewhere, following

in the wake of the mining industry.

The Victorian prospector's hope was to be

answered dramatically in a short while by

123

the spectacular rise of rubber in the early

twentieth century.

The general history of the introduction of

Hevea brasz"llenst"s to Malaya is well known;

it is hardly necessary to retell it here in

great detail. Suffice to say that it took

over a quarter of a century from the first

importation of Hevea seeds from Brazil,

via Kew Gardens in England, to Singapore

in 1877 and then eventually to Malaya in the

early twentieth century.

N egeri Sembilan is one of three Malay

states where rubber cultivation expanded

quickly from the beginning of this century;

the other two are Perak and Selangor.

The successful shipment of rubber from the

Linsum Estate in 1902 signaled a bright

future for the new commercial crop. As

if encouraged by the satisfactory showing

of this first consignment, impetus for rubber

cultivation mounted in N egeri Sembilan.

In 1903 alone there were applications for

rubber land covering roughly 20,000 acres

in the state [Jackson 1968: 225].

Convinced of the future of rubber, the

colonial government encouraged the expan

sion of European-managed rubber estates

in Malaya [Lim 1977 : 72-73] . They

gave them tax incentives and offered them,

with favourable conditions, abandoned

tapioca or gambier estates which needed no

forest clearing for rubber planting. They

earmarked land near roads and railways for

them, and eventually facilitated the im

portation of estate labourers from India.

Buoyed by the rising rubber prices between

1905 and 1906, and assisted by London

capital, rubber cultivation expanded phe

nomenally in Western Malaya between

124

1905 and 1908. The areas planted with

rubber in the three states of Perak,

Selangor, and N egeri Sembilan increased

from 43,410 acres to 166,257 acres between

these years. In Negeri Sembilan alone

they expanded from 5,718 acres to 27,305

acres during the same period [Jackson

1968: 229]. Major centres of rubber

cultivation in N egeri Sembilan at this early

stage were the districts of Seremban and

Pantai (Port Dickson). In these districts

the Chinese were also beginning to plant

rubber, oftentimes mixed with cassava or

gambier.

Rubber prices, and later government

regulations, strongly influenced the sub

sequent expansion of rubber cultivation.

There was a sharp price rise between 1909

and 1910, followed by a severe downfall in

1913. And modest recovery was registered

between 1915 and 1916, only to be counter

manded by a continuous downward trend,

with a minor recovery in 1919, until the

implementation of the Stevenson [rubber

restriction] Scheme (1922-1928). Due

largely to the impact of the restriction

scheme, prices rose again in 1924 and 1925;

they began to drop in 1926 and plunged

during the Great Depression. In response

to this dismal state, the International

Rubber Regulation Agreement, signed by

the British, Dutch, Siamese, and French

governments, was implemented in 1934.

After its renewal in 1938, the scheme

remained effective until the outbreak of the

Second World War. The second restriction

scheme greatly helped to raise and stabilize

rubber prices but never managed to bring

about the kind of recovery effected by the

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

VI History of Rubber Smallholdingin Mukim Johol

By checking through the Mukim Reg

ister, one is able to study the local history

of rubber smallholding in a particular area.

This is what I did for M ukim J ohol by

examining the Mukim Register in the Land

Office of Kuala Pilah.

Table 1 shows the number of approved

applications for rubber lots registered in

the Mukim Register of Mukim Johol. It

covers the pre-war period from 1907 when

the first application for a rubber lot was

approved in Mukim Johol until 1940 when

the expansion of rubber smallholdings had

long ceased to be significant. The years

indicated in the table refer to dates when

applications were approved by the Land

Office, not when extracts were issued.

There was usually a time lag of several

months to a few years between these two

time points. Lots could be utilized once

the application had been approved; but

they could not be mortgaged or transferred

until the extracts were issued. While

Table 1 shows the increase in the number of

smallholdings in M ukim J ohol, Table 2

indicates the area of expansion of rubber

smallholdings in Inas. There is little

difference in growth trends between the two

tables (compare Table 2 with "Inas" in

Table 1), so I basically rely on Table 1 in

the following discussion.

Rubber smallholdings in Mukim Johol

Stevenson Scheme, especially for the period

1924-1925. Throughout the 1930s there

were no more dramatic fluctuations in

rubber prices, such as· were characteristic

of the rubber· market in the first three

decades of the twentieth century.

The expansion of rubber cultivation

generally followed price increases, and later

was influenced increasingly by government

regulations. The 1905-1908 initial boom

was further fueled by high rubber prices

between 1909 and 1911 and was to be

followed by another notable expansion in

1915-1917. During the period of the

Stevenson Scheme (1922-1928), the new

alienation of rubber was prohibited by the

colonial government, and the new planting

of rubber on existing land discouraged.

After a short interval during which this

policy was reversed, new alienation was

again prohibited in 1930, in response to the

serious price drop during the Great De

pression. From 1934 onwards this pro

hibition was accompanied by a ban on the

new planting of rubber in Malaya; these

"double restrictions" were to continue

until the beginning of the war, with the

exception of a short period between 1939

and 1940 [Allen and Donnithorne 1954:

126; Barlow 1978: 71; Bauer 1948: 3, 5,

43, 43, n.1, 65; Lim 1977: 153-154J.

One conclusion we may draw from the

existence of these restrictions is that the

great expansion of rubber cultivation in

Malaya, either in the estate or smallholding

sectors, effectively ended, or at least greatly

slowed down, after the implementation of

the Stevenson Scheme. As will be shown

shortly, this was not exactly what happened

with smallholdings in Mukim

most probably elsewhere

Sembilan.

Johol, and

III Negeri

125

JIU,p" ~ 7lVf~ 29@ 2 "'"

Table 1 Historical Changes in the Number of Smallholdings in Mukim Johol

Inas "Other Johol"

Malay Chinese Indian Total Malay Chinese Indian Total

1907 0 0 0 0 84 2 0 861908 0 0 0 0 52 0 0 521909 0 0 0 0 22 11 0 331910 8 7 0 15 48 17 1 661911 0 3 0 3 4 5 0 91912 3 7 0 10 10 27 0 371913 2 2 0 4 8 17 3 281914 1 2 0 3 3 2 0 51915 13 5 0 18 12 35 3 501916 7 1 0 8 92 39 2 1331917 12 0 0 12 24 19 0 431918 0 0 0 0 4 11 0 151919 1 0 0 1 7 4 0 111920 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1921 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01922 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1923 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1924 3 0 0 3 30 0 0 301925 15 0 0 15 43 0 0 431926 57 0 0 57 81 0 0 811927 21 0 0 21 92 0 0 921928 33 0 0 33 84 0 0 84

1929 8 0 0 8 34 0 0 341930 3 0 0 3 24 0 0 241931 2 0 0 2 5 0 0 51932 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 11933 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 11934 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01935 1 0 0 1 4 0 0 4

1936 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 11937 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 41938 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 2

1939 1 0 0 1 4 0 0 4

1940 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Total 191 27 0 218 780 189 9 978

Source: Mukim Register of Mukim Johol, Land Office of Kuala Pilah

began shortly after the high rubber prices Dato' of Johol (adat chief of Luhak Johol)

of 1905-1906, precisely the years when the had already proposed to the government

first rubber planting boom took place in the a special scheme to encourage rubber

estate sector. As early as late 1905 the smallholdings in Joho!. Local reception of

126

T. KATO: When RubberCame: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

Table 2 Historical Expansion in the Area Size of Smallholdings in Inas

Malay Chinese Total

Acre Rod Pole Acre Rod Pole Acre Rod Pole

1907 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01908 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01909 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01910 25 0 35 41 3 33 67 0 281911 0 0 0 13 3 35 13 3 351912 10 0 16.3 38 1 20 48 1 36.31913 9 1 0 8 0 20 17 1 201914 2 1 29 3 3 19.2 6 1 8.21915 24 3 20 23 3 28 48 3 81916 15 0 7.8 2 2 25 17 2 32.81917 26 2 11 0 0 0 26 2 111918 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01919 6 0 1 0 0 0 6 0 11920 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01921 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01922 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01923 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01924 5 1 33 0 0 0 5 1 331925 47 3 3.3 0 0 0 47 3 3.31926 183 0 20.2 0 0 0 183 0 20.21927 61 1 23.1 0 0 0 61 1 23.11928 86 2 16.6 0 0 0 86 2 16.61929 26 0 39.7 0 0 0 26 0 39.71930 11 3 3 0 0 0 11 3 31931 5 1 0 0 0 0 5 1 01932 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01933 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01934 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01935 4 2 38 0 0 0 4 2 381936 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01937 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01938 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01939 5 0 0 0 0 0 5 0 01940

Total 556 3 17 132 3 20.2 689 2 37.2

Source: Mukim Register of Mukim Johol, Land Office of Kuala Pilah

the scheme was good and the District Officer among British officials. Under the revised

of Kuala Pilah was supportive of it. The scheme, $350 was set aside out of official

revised scheme was finally approved in funds to purchase seeds and set up nurseries

March 1906 after considerable discussions for germination. "It was reported that the

127

Malays of Johol were busily clearing the

lots which the Settlement Officer had

demarcated" [Drabble 1973: 41; see also

Lim 1977: 79]. Unfortunately no fol

lowup report on this scheme is extant.

Some of the "early lots" of "Other Johol"

in Table 1 may have possibly been opened

up under this scheme.

In comparison to "Other Johol" rubber

cultivation in Inas started a little later.

The fact that Inas was isolated from the

Kuala Pilah-Tampin trunk road seems

largely to explain this lag. According to

an old man in Inas, Inas people, without

much previous contact with the outside

world, were ignorant and afraid of trying

new things such as planting rubber.

There were several pioneers in Inas

in the early stages of rubber smallholding.

Among them were Penghulu Sulong (then

Datuk Penghulu Inas) , two lembaga and

Haji J ambi, a wealthy merchant immigrant

from Sumatra [Lewis 1962: 292]. Like

the Dato' of Johol mentioned above,

pioneer smallholders in general were proba

bly people of means in the village.

Although not indicated in Table 1, one

characteristic of early rubber smallholding

in "Other J ohol" was its speculative nature

to a certain degree. For example, in

Kampong Kuala Johol and Kampong

Mesjid Tua, two kampong situated along

the trunk road, there were 86 Malay

smallholdings approved between 1907 and

1909. Out of this figure, 53 lots were sold

to Chinese and 24 to Malays within several

years after their applications were approved,

that is, even before the rubber trees started

bearing. The majority of transactions took

128

place in 1913 when rubber prices dropped.

Apart from possible economic difficulties,

this easy release of lots seems to indicate

a lack of committment to rubber cultivation

among the early Malay smallholders. I

may add here that most of the plots bought

by Chinese were eventually mortgaged to

Chettier moneylenders in 1920. Rubber

prices plunged between the beginning and

the end of 1920 [Barlow 1978: 56].13 )

Evidently the above tendency discerned

in Mukim J ohol was not an isolated case.

After noting a considerable increase in the

number of smallholdings between 1908

and 1912, the Negri Sembilan Administra

tion Report for the year 1912 makes the

following observation:

These figures indicate a steady demand

for land by native cultivators, but would

be more satisfactory if all the small

holdings taken up remained in the hands

of small cultivators. Unfortunately, a

certain number of them are sold after

a year or two, in some cases before they

have even been planted, but usually after

being cleared and planted with rubber

trees, to adjacent estates or persons who

are already considerable land owners, and,

except in the Kuala Pilah, Tampin and

J elebu districts, where the Customary

Lands Enactment is in force, the law

provides no check upon such transactions

and there only in the case of lands entered

13) Kampong Kuala Johol and Mesjid Tua werechosen as samples in my survey of the landregisters because they are located along theKuala Pilah-Tampin trunk road and Malayrubber smallholdings started earlier here thanin other areas of Joho!.

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

as customary lands in the register. (NS

AR 1912, p. 6)

The expansion of rubber smallholdings

in Mukim Johol was concentrated in two

periods before 1940: 1907-1917 and 1924

1930. Active planting during the two

periods was clearly influenced by high

rubber prices.

The first period was obviously instigated

by rising rubber prices between 1905 and

1906, and by the 1905-1908 rubber planting

boom at the estate sector. There was

a "steady demand," according to the Negri

Sembilan Administration Report for the

year 1911, for smallholdings in Negeri

Sembilan from 1909 through 1911: "Proba

bly a large proportion of these lots were

taken up with a view to cultivation of

rubber" (NS AR 1911, p. 5). (The

Administration Report gives figures of

smallholdings only from 1909 to 1911 but

the "steady demand" must have started

earlier than 1909.)

Above all, the period between 1915 and

1917 is considered "an era of rapid planting

on the part of smallholders, both Malay

and Chinese, particularly in the western

Malay States" [Jackson 1968: 257J. The

District Officer of Kuala Pilah made the

following comment on the condition in his

district in 1916:

The local Malays were badly bitten with

the rubber craze, partly no doubt owing

to the example set by Europeans and

others, but chiefly I think, as a large

number of small holdings came into

bearing during 1916 and it was seen how

profitable a few acres of rubber in bearing

are at present. Hundreds of Malays

thronged the office daily clamouring for

land and the books [of the M ukim

RegisterJ had to be closed on two oc

caSIOns during the year. (AR KP

1916, p. 3)

The second rubber planting boom was

preceded by several years of no active

planting. The lack of action was caused

by price falls and the prohibition of new

alienation during the Stevenson Scheme.

Difficulties encountered by the rubber

industry in production and exportation

under war-time conditions were not en

couraging either for the expansion of rubber

cultivation.

In Table 1 it is noteworthy that no more

Chinese (and Indian) smallholdings are

observable after 1919. Probably the Malay

Reservations Enactment is largely re

sponsible for this phenomenon. The

enactment, which purports to preserve

"Malay lands or reservations" under Malay

ownership and for future Malay occupation,

was initially drafted in July 1913. This was

a reaction to the contemporary trend

whereby many Malay smallholdings were

sold to non-Malays as discussed above.

After the enforcement of the Malay Reser

vations Enactment, alienation and land

transactions in the smallholding sector

became increasingly difficult and unat

tractive to non-Malays. The implemen

tation of the enactment was scheduled for

January 1st 1914 but concrete steps were

not taken until 1915 [Drabble 1973: 102].

In Negeri Sembilan, it was only in 1916

129

that the enactment was actually imple

mented in most mukim of Kuala Pilah,

Tampin and J elebu. As far as Mukim

J ohol is concerned, it was most probably

effected in 1917.14 )

It is surprising that the second period of

the rubber planting boom (1924-1930) was

as important as, or in case of Inas more

important than, the first period in Mukim

Johol. This is particularly so because new

alienation was supposedly prohibited in

Malaya after the Stevenson Scheme (1922

1928), apart from the exceptional years of

14) This delay in implementing the enactment in thethree districts of Negeri Sembilan is explainedas follows: "When the Enactment of 1913 waspassed, this course did not seem necessaryowing to the protection against alienation ofMalay customary holdings afforded by theCustomary Tenure Enactment of 1909, whichapplies to the three districts of Kuala Pilah,Tampin and J elebu, but to secure this protectionit was necessary that the lands should beregistered as customary-Le., lands successionto which follows the 'adat perpateh,' and thiscourse, though suitable in the case of kampongand sawah lands, was found irksome in practiceif applied to lands taken up merely to be cultivated for profit. On the other hand, if theseholdings were not registered as customary,there was nothing to prevent their sale later onto Europeans or Chinese, even though they weresituated in the midst of Malay holdings, andafter careful consideration the State Councildecided on the course which was adopted ashaving the advantage of allowing Malays totake up land in their own mukims to cultivatefor profit which they would be free to dispose ofwithout obtaining the consent of the tribe andat the same time securing that, if the lands werein a locality predominantly Malay, they shouldnot pass into non-Malay hands" (NS AR1916, pp. 9-10). In 1916 "A further reservation at Inas is under consideration" (/oc. cit.).The expansion of Malay reservations continuedin the three districts in 1917 (NS AR 1917,p.3).

130

Table 3 Number of "Nil Lots" in Mukim Johol

Inas "Other J ohol" Total

1925 2 4 61926 11 24 351927 12 75 871928 31 74 1051929 3 18 211930 0 22 221931 1 4 51932 0 1 11933 0 1 11934 0 0 0

1935 1 4 51936 0 0 0

1937 0 1 11938 0 0 01939 1 0 11940 0 0 0

Total 62 228 290

Source: M ukim Register of M ukim Johol, LandOffice of Kuala Pilah

1928-1930 and 1939-1940 [Bauer 1948: 3,

5, 43, 43, n.l, 65].Part of the explanation for this "anomaly"

is found in the "nature of cultivation"

clause in the Mukim Register. Many

"nil," which were not extant in the earlier

period, are found In the "nature of

cultivation" clause among the entries made

after 1924, that is, during the second rubber

planting boom (Table 3). I equated the

"nil" with "rubber" in tabulating Table

1 for the following reasons. An official at

the Land Office of Kuala Pilah with long

experience in land administration informed

me that the "nil" was in reality the same as

"rubber." Some entries under "nil" in

the Mukim Register had "rubber" written

in pencil after the "nil." The tax rates for

"nil lots" were exactly the same as those of

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

"rubber lots," which were much higher than

those of sawah or kampong.

The above observation strongly suggests

that rubber smallholdings in Mukim Johol

expanded significantly under the guise of

"nil" when new alienation for rubber land

was prohibited. In addition, "rubber lots"

themselves increased during the second

period (compare Tables 1 and 3). In fact,

rubber holdings registered as such in both

the estate and smallholding sectors in Negeri

Sembilan as a whole increased remarkably

between 1917 and 1939 (see Table 5 on

page 150).15)

Old people in Inas remember the period

of the second rubber restriction scheme as

years of great prosperity. This IS so

despite the fact that rubber prices during

this period were not as high as during the

time of the Stevenson Scheme. One of the

reasons for this incongruity lies in the fact

that a far greater number of Malay peasants

were involved in rubber tapping during

the second restriction scheme than during

the first. It is important to realize that the

cumulative total of smallholdings acquired

and planted from 1907 through to the

1920s were practically all at the bearing

stage when the International Rubber

Restriction Agreement was implemented

in 1934. We must also recall that, prior

to the implementation of the Malay Reser

vations Enactment (around 1917 in Mukim

Johol), many Malay lots were sold to non-

15) Unfortunately I do not know how common"nil lots" were in other districts of NegeriSembilan and whether they were counted as"rubber lots" in calculating macro statisticssuch as those listed in Table 5.

Malays who themselves, until that time, had

been active in opening up rubber small

holdings. In this sense, the expansion of

smallholdings in the 1920s was critical

because it signified a more or less pure

gain in the number of Malay holdings and

thus enlarged the involvement of the

Malays in rubber tapping as either owner

tappers or share-tappers.16)

It is difficult to estimate to what degree

the above observation is true for the rest

of N egeri Sembilan or to other Federated

Malay States. Judging from the general

observation that new land alienation and

planting were either prohibited or dis

couraged during the two restriction schemes,

the Johol case might have been an ex

ceptional one. Nevertheless, a further

inquiry into this question is needed to

assess the magnitude and timing of the

economic impact of rubber cultivation in

rural Malaya. As far as Mukim J ohol is

concerned, the latter half of the 1930s is

far more important in this respect than that

of the 1920s.

16) It is also possible that Chinese who hadpurchased Malay lots in the early stage ofrubber expansion later resold them to Malaysafter the Malay Reservations Enactment.However, this possibility is not substantiatedin M ukim Jaha!. A cursory review of Chineselots in Kampong Kuala Johol and KampongMesjid Tua reveals that few, if any, of theChinese lots were sold back to Malays beforethe Second World War. However, this kind oftransaction became common in the early 1950s,especially in 1954. This was probably relatedto the Emergency (1948-1960) and also to theinitiation of a government-sponsored rubberreplanting scheme for smallholders in 1953.

131

VII Implications of Rubber .Smallholding

It is said that Malay settlements in the

nineteenth century tended to lack perma

nence. Rural populations often dispersed

in response to political oppression, economic

exploitation, wars, new economic oppor

tunities, epidemics, or soil deterioration

[Gullick 1958J. The establishment of

British control offered the Malay peasantry

a relatively stable political environment and

thus one more congenial to a settled

existence. Rubber, a perennial crop which

must mature for six to seven years until the

trees can be tapped, further enhanced this

tendency. Note, however, that the colonial

introduction of land registers cut both ways

in this context. On the one hand, land

registration increased the peasants' attach

ment to land ownership, and thus, to some

extent, to the land itself; the institutionali

zation of land ownership, on the other hand,

enhanced the sense of deprivation among

those who owned little or no land and thus

encouraged them to migrate when a better

chance for land ownership became available

outside their village. (The FELDA

scheme owes part of its success to this

"peasant psychology" created after the

colonial introduction of land registers.)

The fact that land is now a liquid com

modity, theoretically easily exchanged for

money, also tends to enhance this mobility;

small landowners can dispose of their

existing lands and leave for a new

settlement.

The eventual spread of rubber over vari-

132

ous parts of British Malaya was also

instrumental for the rapid expansion of the

transportation system, railways as well as

roads, III the peninsula [Kaur 1985].

One by-product of this was that dusun or

orchards became an important economic

asset, as fruit, an easily perishable commod

ity, could now be marketed in towns and

cities largely to Chinese. For example, after

the town of Kuala Pilah was connected with

Bahau by rail in 1910, durian from villages

around Kuala Pilah became a lucrative

commodity (AR KP 1912, p. 6). Likewise,

durian harvested at Chiong in Inas became

marketable only after a three-foot road

(jalan Hga kaki) was built in the 1920s

between Sekolah Melayu Inas and Kuala

Johol, a junction on the Kuala Pilah

Tampin-Malacca trunk road.

In step with these developments in the

transportation systems, Malay settlement

patterns also underwent a transformation.

According to old people in Inas, the best

locations for houses were considered to be

near sawah, streams or footpaths connecting

settlements and sawah. In time past it was

common for the front part of the house to

face the sawah. As cart roads and later

metalled roads were constructed, more and

more houses began to be built along them

(see also Gullick [1958: 27] and Kaur

[1985: 13-14]). This tendency was a pre

cursor of contemporary Malay settlement

patterns where most houses are lined up

along the roads, usually away from the

sawah. A tangible sign of change in

Malay settlement patterns is still occasion

ally seen in the location of mosques. Old

mosques tended to be built near a river or

T. KATO: When Rubber Came: The Negeri Sembilan Experience

stream. Nowadays, if a road is located

away from the river, a new mosque is

usually constructed by the roadside.

(Moslems need access to water for ablutions

before their daily prayers; the availability

of piped water now allows flexibility in the

choice of mosque locations.) In the

countryside of Kuala Pilah, one sometimes

comes across abandoned mosques in a

dilapidated state, away from the road but

near a river.

Chinese involvement m rubber culti

vation signified their decision to make

Malaya a place of long-term or permanent,

rather than temporary, residence. In

cassava cultivation, they could reap quick

returns and even squeeze out profits from

an entire estate within several years.

Rubber cultivation, in contrast, required

a long-range committment. Change in

the Chinese orientation in this respect is

reflected in the development of Pekan

Johol. Reportedly it was already a sizable

Chinese settlement in the first decade of the

twentieth century. However, shops still

had atap-roofs and atap-walls. The first

brick-built shop (kedai batu) appeared in

1918. A Chinese primary school, sup

ported by well-to-do merchants of the

pekan, came into being in 1924. This

meant a complete departure from the "era

of tin-mines and cassava estates" when

families were a minority among the male

dominated Chinese population In rural

N egeri Sembilan.

Closer relationships between some

Chinese and Malay individuals continued

in the twentieth century when the rural

rubber market was more or less controlled

by Chinese merchants. It seems that

interracial relations then were not as

problematic as they were to become after

the Second W orId War. "[T]he tendency