What is risk management? COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL€¦ · The biggest fraud of all time A number of...

Transcript of What is risk management? COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL€¦ · The biggest fraud of all time A number of...

1

What is risk management?

The biggest fraud of all timeA number of banks have succeeded in losing huge sums of money in theirtrading operations, but Societe Generale (‘SocGen’) has the distinction of losingthe largest amount of money as the result of a fraud. This took place in 2007, butwas uncovered in January 2008. SocGen is one of the largest banks in Europe andthe size of the fraud itself is staggering; SocGen estimated that it lost 4.9 billionEuros as a result of unwinding the positions that had been entered into. Witha smaller firm this could well have caused the bank’s collapse, as happened toBarings in 1995, but SocGen is large enough to weather the storm. The employeeresponsible was Jerome Kerviel, who did not profit personally (or at least onlythrough his bonus payments being increased). In effect, he was taking enormousunauthorized gambles with his employer’s money. For a while these gamblescame off, but in the end they went very badly wrong.

In America the news broke on January 24, 2008, when the New York Timesreported as follows:

‘Societe Generale, one of the largest banks in Europe, was throwninto turmoil Thursday after it revealed that a rogue employee hadexecuted a series of “elaborate, fictitious transactions” that cost thecompany more than $7 billion US, the biggest loss ever recorded inthe financial industry by a single trader.

Before the discovery of the fraud, Societe Generale had been preparingto announce pretax profit for 2007 of ¤5.5 billion, a figure that Bouton(the Societe Generale chairman) said would have shown the company’s“capacity to absorb a very grave crisis.” Instead, Bouton – who is for-going his salary through June as a sign of taking responsibility – saidthe “unprecedented” magnitude of the loss had prompted it to seek

Business Risk Management: Models and Analysis, First Edition. Edward J. Anderson.© 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.Companion website: www.wiley.com/go/business_risk_management

COPYRIG

HTED M

ATERIAL

2 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

about ¤5.5 billion in new capital to shore up its finances, a move thatsecures the bank against collapse.

Societe Generale said it had no indication whatsoever that the trader –who joined the company in 2000 and worked for several years in thebank’s French risk-management office before being moved to its DeltaOne trading desk in Paris – “had taken massive fraudulent directionalpositions in 2007 and 2008 far beyond his limited authority.” The bankadded: “Aided by his in-depth knowledge of the control proceduresresulting from his former employment in the middle-office, he man-aged to conceal these positions through a scheme of elaborate fictitioustransactions.”

When the fraud was unveiled, Bouton said, it was “imperative thatthe enormous position that he had built, and hidden, be closed outas rapidly as possible.” The timing could hardly have been worse.Societe Generale was forced to begin unwinding the trades on Mon-day “under conditions of extreme market volatility,” Bouton said, asglobal stock markets plunged amid mounting fears of an economicrecession in the United States.’

A story like this inevitably prompts the question: How could this have hap-pened? Later in this chapter we will give more details about what went wrong.SocGen was a victim of an enormous fraud but the defense lawyers at Kerviel’strial argued that the company itself was primarily responsible. Whatever degreeof blame is assigned to SocGen, it clearly paid a heavy price. It is easy to bewise after the event, but good business risk management calls on us to be wisebeforehand. Later in this chapter we will discuss the things that can be learntfrom this episode (and that need to be applied in a much wider sphere than justthe world of banks and traders.)

1.1 Introduction

In essence, risk management is about managing effectively in a risky and uncer-tain world. Banks and financial services companies have developed some of thekey ideas in the area of risk management, but it is clearly vital for any manager.All of us, every day, operate in a world where the future is uncertain.

When we look out into the future there is a myriad of possibilities: there canbe no comprehension of this in its totality. So our first step is to simplify in a waythat enables us to make choices amidst all the uncertainty. The task of findinga way to simplify and comprehend what the future might hold is conceptuallychallenging and different individuals will do this in different ways. One approachis to set out to build, or imagine, a set of different possible futures, each of whichis a description of what might happen. In this way we will end up with a rangeof possible future scenarios that are all believable, but have different likelihoods.

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 3

Though it is obviously impossible to describe every possibility in the future, atleast having a set of possibilities will help us in planning.

One way to construct a scenario is to think of chains of linked events: if onething happens then another may follow. For example, if there is a typhoon inHong Kong, then the shipment of raw materials is likely to be late, and if thishappens then we will need to buy enough to deal with our immediate needs froma local supplier, and so on. This creates a causal chain.

A causal chain may, in reality, be a more complicated network of linked events.But in any case it is often helpful to identify a particular risk event within the chainthat may or may not occur. Then we can consider both the probability of the riskevent occurring and also the consequences and costs if it does. In the example ofthe typhoon in Hong Kong, we need to bear in mind both the probability of thetyphoon and the costs involved in finding an alternative temporary source.

Risk management is about seeking better outcomes, and so it is critical toidentify different risk events and to understand both their causes and consequences.Usually risk in this context refers to something that has a negative effect, so thatour interest in the causes of negative risk events is to reduce their probability or,better still, eliminate them altogether. We are concerned about the consequencesof risk events so that we can act beforehand in a way that reduces the costs if anegative risk event does occur. The open-ended nature of this exercise makes itimportant to concentrate on the most important causal pathways – we can think ofthis as identifying risk drivers.

At the same time as looking at actions specifically designed to reduce risk, wemay need to think about the risk consequences of management decisions that wemake. For example, we may be considering moving to an overseas supplier whois able to deliver goods at a lower price but with a longer lead time, so that orderswill need to be placed earlier: then we need to ask what extra risks are involvedin making this change. In later chapters we will give much more attention to theproblems of making good decisions in a risky environment.

Risk management involves planning and acting before the risk event. Thisis proactive rather than reactive management. We don’t just wait and see whathappens, with the hope that we can manage our way through the consequences;instead we work out in advance what might happen and what the consequencesare likely to be. Then we plan what we should do to reduce the probability ofthe risk event and to deal with the consequences if it occurs.

Sometimes the risk event is not in our control; for example, we might bedealing with changes in exchange rates or government regulation – usually this iscalled an external risk. On other occasions we can exercise some control over therisk events, such as employee availability, supply and operations issues. These arecalled internal risks. The same distinction between what we can and cannot controloccurs with consequences too. Sometimes we can take actions to limit negativeconsequences (like installing sprinklers for a fire), but at other times there arelimits to what we can do and we might choose to insure against the event directly(e.g. purchasing fire insurance).

4 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

We will use the term risk management to refer to the entire process:

• Understanding risk: both its drivers and its consequences.

• Risk mitigation: reducing or eliminating the probability of risk events aswell as reducing the severity of their impact.

• Risk sharing: the use of insurance or similar arrangement so that some ofthe risk is transferred to another party, or shared between two parties insome contractual arrangement.

The risk framework we are discussing makes it sound as though all risk is bad,but this is misleading in two ways. First we can use the same approach to considergood outcomes as well as bad ones. This would lead us to try to understand themost important causal chains, with the aim of maximizing the probability of apositive chance event, and of optimizing the benefits if this event does occur.Second we need to recognize that sometimes the more risky course of action isultimately the wiser one. Managers are schizophrenic about risk. Most see risktaking as part of a manager’s role, but there is a tendency to judge whether adecision about risk was good or bad simply by looking at the results. Thoughit is rarely put in these terms, the idea seems to be that it is fine to take risksprovided that nothing actually goes badly wrong! Occasionally managers mighttalk of ‘controlled risk’ by which they mean a course of action in which theremay be negative consequences but these are of small probability and the size ofthe cost is tolerable.

In their discussion of the agile enterprise, Rice and Franks (2010) say, ‘Whileuncertainty impacts risk, it does not necessarily make business perilous. In fact,risk is critical to any business – for nothing can improve without change – andchange requires risk.’ Much the same point was made by Prussian MarshallHelmuth von Moltke in the mid-1800s: ‘First weigh the considerations, then takethe risks.’

Our discussion so far may have implied an ability to list all the risks and dis-cuss the probability that an individual risk event occurs. But often there is no wayto identify all the possible outcomes, let alone enter into a calculation of the prob-ability of their occurrence. Some people use the term uncertainty (rather than risk)to refer to this idea. Frank Knight was an economist who was amongst the firstto distinguish clearly between these two concepts and he used ‘risk’ to refer tosituations where the probabilities involved are computable. In many real environ-ments there may be a total absence of information about, or awareness of, somepotentially significant event. In a much-parodied speech made at a press briefingon February 12, 2002, former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said:

‘There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know.There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that wenow know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns.These are things we do not know we don’t know.’

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 5

In Chapter 8 we will return to the question of how we should behave in situationswith uncertainty, when we need to make decisions without being able to assignprobabilities to different events.

1.2 Identifying and documenting risk

Many companies set up a formal risk register to document risks. This enables themto have a single point at which information is gathered together and it encouragesa careful assessment of risk probabilities and likely responses to risk events.

A carefully documented risk management plan has a number of advantages.There is first of all a benefit in making it more likely that risk will be man-aged appropriately, with major risks identified and appropriate measures taken.Secondly there is an advantage in defining the responsibility for managing andresponding to particular categories of risk. It is all too easy to find yourself in acompany in which something goes wrong and no person or department admitsto being the responsible party.

Moreover, a risk management plan allows stakeholders to approve the riskmanagement approach and helps to demonstrate that the company has exercisedan appropriate level of diligence in the event that things do go wrong.

There are really three steps in setting up a risk register:

1. Identify the important risk events. The first step is to make some kind oflist of different risks that may occur, and in doing this a systematic processfor identifying risk can be helpful. A good starting point is to think aboutthe context for the activity: the objectives; the external influences; thestages that are gone through. The next step is to go through each elementof the activity asking what might happen that could cause external factorsto change, or that could affect the achievement of any objective.

2. Understand the causes of the risk events. Risk does not occur in a vacuum.Having identified a set of risk events, the next step is to come to gripswith the factors that are involved in causing the risk events. In orderto understand what can be done to avoid these risks, we should ask thefollowing questions, for each risk:

• How are these events likely to occur?

• How probable are these events?

• What controls currently exist to make this risk less likely?

• What might stop the controls from working?

3. Assess the consequences of the risk events. The final step is to understandwhat may happen as a result of these risk events. The aim is to find waysto reduce the bad effects. For each risk we will want to know:

• Which stakeholders might be involved or affected? For example, doesit affect the return on share capital for shareholders? Does it affect the

6 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

assurance of payment for suppliers? Does it affect the security that isoffered to our creditors? Does it affect the assurance of future employ-ment for our employees?

• How damaging is this risk?

• What controls currently exist to make this risk less damaging?

• What might stop the controls from working?

At the end of this process we will be in a better position to build the riskregister. This will indicate, for each risk identified:

• its causes and impacts;

• the likelihood of this risk event;

• the controls that exist to deal with this risk;

• an assessment of the consequences.

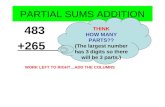

Because the risk register will contain a great many different risks, it is impor-tant to focus on the most important ones. We want to construct some sort ofpriority rating – giving the overall level of risk. This then provides a tool so thatmanagement can focus on the most important risk events and then determine arisk treatment plan to reduce the level of risk. The most important risks are thosewith serious consequences that are relatively likely to occur. We need to combinethe likelihood and the impact and Figure 1.1 shows the type of diagram that isoften used to do this, with risk levels labeled L = Low; M = Medium; H =High; and E = Extreme.

This type of diagram of risk levels is sometimes called a heat map, and oftenred is used for the extreme risk boxes; orange for the high risks; and yellowfor the medium risks. It is a common tool and is recommended in most riskmanagement standards. It should be seen as an important first step in drawing

Very likely

Likely

Moderate

Unlikely

Rare

L

LL

L

L

H H

H

H

H

HH

H

E E

E

E

E

E

E

EM

M

M

M

Magnitude of Impact

Insignificant

Like

lihoo

d

MinorModerate

MajorCatastrophic

Figure 1.1 Calculating risk level from likelihood and impact.

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 7

up a risk management plan, prior to making a much fuller investigation of somespecific risks, but nevertheless there are some significant challenges associatedwith the use of this approach.

One problem is related to the use of a scale based on words like ‘likely’or ‘rare’: these terms will mean very different things to different people. Somepeople will use a term like ‘likely’ to mean a more than two thirds chanceof occurring (this is the specific meaning that is ascribed in the IPCC climatechange report). But in a risk management context, quite small probabilities overthe course of a year may seem to merit the phrase ‘likely’.

The use of vague terms in a scale of this sort will make misunderstandings farmore likely. Douglas Hubbard describes an occasion when he asked a manager‘What does this mean when you say this risk is “very likely”?’ and was told thatit meant there was about a 20% chance of it happening. Someone else in theroom was surprised by the small probability, but the first manager responded,‘Well this is a very high impact event and 20% is too likely for that kind ofimpact.’ Hubbard describes the situation as ‘a roomful of people who looked ateach other as if they were just realizing that, after several tedious workshopsof evaluating risks, they had been speaking different languages all along.’ Thisstory illustrates how important it is to be absolutely clear about what is meantwhen discussing probabilities or likelihoods in risk management.

The heat map method is clearly a rough and ready tool for the identification ofthe most important risks. But its greatest value is in providing a common frameworkin which a group of people can pool their knowledge. Far too often the methodologyfails to work as well as it might, simply because there has not been any prioragreement as to what the terms mean. A critical point is to have a common viewof the time frame or horizon over which risks are assessed. Suppose that thereis a 20% probability of a particular risk event occurring in the next year, but thegroup charged with risk management is using an implicit 10-year time horizon.This would certainly allow them to assess the risk as very likely, since, if each yearis independent of the last and the probability does not vary, then the probabilitythat the event does not occur over 10 years is 0.810 = 0.107. So there is a roughly90% chance that the event does occur at some point over a 10-year period.

More or less the same argument applies to the terms used to identify themagnitude of the impact. It will not be practicable to give an exact dollar figureassociated with losses, just as there is little point in trying to ascribe exactprobabilities to risk events. But it is worthwhile having a discussion on whata ‘minor’ or a ‘moderate’ impact really means. For example, we might initiate aconversation about the evaluation we would give for the impact of an event thatled to an immediate 5% drop in the company share price.

1.3 Fallacies and traps in risk management

In this introductory chapter it is appropriate to give some ‘health warnings’ aboutthe practice of risk management. These are ideas about risk management that canbe misleading or dangerous.

8 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

It is worth beginning with the observation that society at large is increasinglyintolerant of risk which has no obvious owner – no one who is responsible andwho can be sued in the event of a bad outcome. Increasingly it is no longeracceptable to say ‘bad things happen’ and we are inclined to view any bad eventas someone’s fault. This is associated with much management activity that couldbe characterized as ‘covering one’s back’. The important thing is no longer therisk itself but the demonstration that appropriate action has been taken so that therisk of legal liability is removed. The discussion of risk registers in the previoussection demonstrates exactly this divergence between what is done because itbrings real advantage, and what is done simply for legal reasons. Michael Powermakes the case that greater and greater attention is placed on what might be calledsecondary risk management, with the sole aim of deflecting risk away from theorganization or the individuals within it. It is fundamentally wrong to spend moretime ensuring that we cannot be sued than we do in trying to reduce the dangersinvolved in our business. But in addition to questions of morality, a focus onsecondary risk management means we never face up to the question of whatis an appropriate level of risk, and we may end up losing the ability to makesound judgments on appropriate risks: the most fundamental requirement for riskmanagement professionals.

Another trap we may fall into is the feeling that good risk managementrequires a scenario-based understanding of all the risks that may arise. Often thisis impossible, and trying to do so will distract attention from effective manage-ment of important risks. As Stulz (2009) argues, there are two ways to avoid thistrap. First there is the use of statistical tools (which we will deal with in muchmore detail in later chapters).

‘Contrary to what many people may believe, you can manage riskswithout knowing exactly what they are – meaning that most of whatyou’d call unknown risks can in fact be captured in statistical riskmanagement models. Think about how you measure stock price risk.. . . As long as the historical volatility and mean are a good proxy forthe future behavior of stock returns, you will capture the relevant riskcharacteristics of the stock through your estimation of the statisticaldistribution of its returns. You do not need to know why the stockreturn is +10% in one period and −15% in another.’

The second way to avoid getting bogged down in an unending set of almostunknowable risks is to recognize that important risks are those that make adifference to management decisions. Some risks are simply so low in probabilitythat a manager would not change her behavior even if this risk was brought toher attention. This is like the risk of being hit by an asteroid – it must have somesmall probability of occurring but it does not change our decisions.

A final word of caution relates to the use of historical statistical informationto project forward. We may find a long period in which something appears to bevarying according to a specific probability distribution, only to have this changequite suddenly. An example with a particular relevance for the author is in the

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 9

1.6

Jan

2004

Jan

2005

Jan

2006

Jan

2007

Jan

2008

Dec 2

008

1.8

2

2.2

2.4

2.6

2.8

Figure 1.2 Australian dollars to one British pound 2004–2008.

exchange rate between the Australian dollar and the British pound. The graph inFigure 1.2 shows what happened to this exchange rate over a five-year period from2004 to 2008.

The weekly data here have a mean of 2.38 Australian dollars per pound andthe standard deviation is 0.133. Fifteen months later, in March 2010, the rate hadfallen to 1.65 (and continued to fall after that date). Now, if weekly exchangerate data followed a normal distribution then the chance of observing a valueas low as 1.65 (more than five standard deviations below the mean) would becompletely negligible. Obviously the foreign exchange markets do not behavein quite the way that this superficial historical analysis suggests. Looking over alonger period and considering also other foreign exchange rates would suggestthat the relatively low variance over the five-year period taken as a base wasunusual. In this case the fallout from the global financial crisis quickly led toexchange rate values that reflect historically very high levels for the Australiandollar and a low level for the British pound.

We may be faced with the task of estimating the risk of certain events on thebasis of statistical data but without the benefit of a very long view and with noopportunity to compare any related data. In this situation all that we might have toguide us is a set of data like Figure 1.2. Understanding how hard it is in a foreignexchange context to say what the probabilities are of certain outcomes should helpus to be cautious when faced with the same kind of task in a different context.

1.4 Why safety is different

This book is about business risk management and is aimed at those who willhave management responsibility. There are significant differences between howwe may behave as managers and how we behave in matters of our personalsafety. Every day as we grow up, and throughout our adult lives, we makedecisions which involve personal risk. The child who decides to try jumpingoff the playground swing is weighing up the risk of getting hurt against theexcitement involved. And the driver who overtakes a slower vehicle on the road

10 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

is weighing up the risks of that particular road environment against the time orfrustration saved. In that sense we are all risk experts; it’s what we do every day.

It is tempting to think about safety within the framework we have laid out ofdifferent risk events, each with a likelihood and a magnitude of impact. With thisapproach we could say that a car trip to the shops involves such a tiny likelihoodof being involved in a collision with a drunk driver that the overall level of riskis easily outweighed by the benefits. But there are two important reasons whythinking in this way can be misleading.

First we need to consider not only the likelihood of a bad event, but also itsconsequences. And if I am worried about someone else driving into me, then theconsequence might be the loss of my life. Just how does that get weighed upagainst the inconvenience of not using a car? Most of us would simply be unableto put a monetary value on our own lives, and no matter how small the chanceof our being killed in a car crash, the balance will tilt against driving the car ifwe make the value of our life high enough. But yet we still drive our cars anddo all sorts of other things that carry an element of personal risk.

A second problem with treating safety issues in the same way as other risksis that the chance of an accident is critically determined by the degree of caretaken by the individual concerned. The probability of dying in a car crash onthe way to the shops is mostly determined by how carefully I drive. This makesmy decision on driving a car different to a decision on traveling by air, whereonce on board I have no control over the level of risk. However, there are manysituations where being careful will dramatically reduce the risk to our personalsafety. Paradoxically, the more dangerous we perceive the activity to be then themore careful we are. The risks from climbing a ladder may end up being greaterthan from using a chain saw if we believe that the ladder is basically safe, butthat the chain saw is extremely dangerous.

A better way to consider personal safety is to think of each of us as havingan in-built ‘risk thermostat’ that measures our own comfort level with differentlevels of risk. As we go about our lives there comes a time with certain activitieswhen we start to feel uncomfortable with the risk we are taking; this happenswhen the amount of risk starts to exceed our own risk thermostat setting. The riskwe will tolerate varies according to our own personalities, our age, our experienceof life, etc. But if the level of risk is below this personal thermostat setting thenthere is very little that holds us back from increasing the risk. So, if driving seemsrelatively safe then we will not limit our driving to occasions when the benefitsare sufficiently large. John Adams points out that some people will actively seekrisk so that they return to the risk thermostat setting which they prefer. So, indiscussing the lives that might be saved if motorcycling was banned, he points outthat, ‘If it could be assumed that all the banned motorcyclists would sit at homedrinking tea, one could simply subtract motorcycle accident fatalities from thetotal annual road accident death toll. But at least some frustrated motorcyclistswould buy old bangers and try to drive them in a way that pumped as muchadrenaline as their motorcycling’.

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 11

These are important issues and need to faced by businesses in which healthand safety are big concerns, such as mining. If the aim is to get as close as possibleto eliminating accidents in the workplace, then it is vital to pay attention to theworkplace culture, which can have a role in resetting the risk thermostat of ouremployees to a lower level.

1.5 The Basel framework

The Basel Accords refer to recommendations made by the Basel Committee onBanking Supervision about banking regulations. The second of these accords(Basel II) was first published in 2004 and defines three different types of risk forbanks – but the framework is quite general and can apply to any business.

Market risk. Market risk focuses on the uncertainties that are inherent in marketprices which can go up or down. Market risk applies to any uncertaintywhere the value is dependent on prices that cannot be predicted fully inadvance. For example, we might build a plant to extract gold from a low-yield resource, but there is a risk that the gold price will drop and ourplant will no longer be profitable. This is an example of a commodity risk.Other types of market risk are equity risk (related to stock prices and theirvolatility); interest rate risk; and currency risk (related to foreign exchangerates and their volatility).

Credit risk. Any business will be involved in many different contractualarrangements. If the counterparty to the contract does not deliver whatis promised then legal means can be used to extract what is owed. But thisassumes that the counterparty still has funds available. Credit risk is therisk of a counterparty to a contract going out of business. For example, abusiness might deliver products to its customers and have 30-day paymentterms. If the customer goes out of business there may be no way of gettingback more than a small percentage of what is owed. In its most direct form,the contract is a loan made to another party and credit risk is about notbeing repaid due to bankruptcy.

Operational risk. Operational risk is about something going badly wrong. Thiscategory of risk includes many of the examples we have discussed so farthat are associated with negative risk events. Operational risk is definedas arising from failures in internal processes, people or systems, or due toexternal events.

Since we are interested in more general risk management concerns, not justrisk for banks, it is helpful to add a fourth category to the three discussed byBasel II.

Business risk. Business risk relates to those parts of our business value propo-sition where there is considerable uncertainty. For example, there may be

12 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

a risk associated with changes in costs, or changes in customer demand,or changes in the security of supply of raw materials. Business risk is likemarket risk but does not relate directly to prices.

Both market risk and credit risk are, to some extent, entered into deliberatelyas a result of calculation. Market risk is expected, and we can make calculationson the basis of the likelihood of different market outcomes. Business risk alsooften has this characteristic: for example, most businesses will have a clear ideaof what will happen under different scenarios for customer demand. Credit risk isalways present, and in many cases we assess credit risk explicitly through creditratings. But operational risk is different: it is not entered into in the expectationof reward. It is inherent and is, in a sense, the unexpected risk in our business.It may well fit into the ‘unknown unknown’ description in the quotation fromRumsfeld that we gave earlier. Usually operational risk involves low-probabilityand high-severity events and this makes it particularly challenging to deal with.

1.6 Hold or hedge?

When dealing with market or business risk a manager is often faced with anongoing risk, so that it recurs from day to day or month to month. In this casethere is the need to take strategic decisions related to these risks.

An example of a recurring risk occurs with airlines who face ongoing uncer-tainty related to the price of fuel (which can only be partially offset by addingfuel surcharges). The question that managers face is: when to hold on to thatrisk, when to insure or hedge it, and when to attack the risk so that it is reduced?

A financial hedge is possible when we can buy some financial instrumentto lessen the risk of market movements. For example, a power utility companymight trade in futures for gas prices. If the utility is buying gas and sellingelectricity then it is exposed to a market risk if the price of gas rises and it isnot able to raise the price of electricity to the same extent. By holding a futurescontract on the gas price, the company can obtain a benefit when the price ofgas increases: if the utility knows how much gas it will purchase then the neteffect will be to fix the gas price for the period of the contract and eliminatethis form of market risk. Even if the utility cannot exactly predict the amount ofgas it will burn, there will still be the opportunity to hedge the majority of itspotential losses from gas price rises.

Sometimes we have an operational hedge which achieves the same thingas a financial hedge through the way that our operations are organized. Forexample, we may be concerned about currency risk if our costs are primarily inUS dollars but our sales are in the Euro zone. Thus, if the Euro’s value fallssharply relative to the US dollar, then we may find our income insufficient tomeet our manufacturing expenses even though our sales have remained strong. Anoption is to buy a futures contract which has the effect of locking in an exchangerate. However, another ‘operational hedge’ could be achieved by moving some

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 13

of our manufacturing activity into a country in the Euro zone, so that more ofour costs occur in the same currency as the majority of our sales.

In holding on to a risk the company deliberately decides to accept the vari-ation in profit which results. This may be the best option when a company hassufficient financial resources, and when it has aspects of its operations that willlimit the consequences of the risk. For example, a vertically integrated powerutility company that sets the price of electricity for its customers may decidenot to fully hedge the risks associated with rises in the cost of gas if there areopportunities to quickly change the price of the electricity that it sells in orderto cover increased costs of generation.

1.7 Learning from a disaster

We began this chapter with the remarkable story of Jerome Kerviel’s massivefraud at Societe Generale, which fits into the category of operational risk. Now wereturn to this example with the aim of seeing what can be learnt. To understandwhat happened we will start by giving some background information on theworld of bank trading. A bank, or any company involved in trading in a financialmarketplace, will usually divide its activities into three areas. First the tradersthemselves: these are the people who decide what trades to make and whento make them (the ‘front office’). Second, a risk management area responsiblefor monitoring the traders’ activity measuring and modeling risk levels etc. (the‘middle office’). And finally an area responsible for carrying out the trades,making the required payments and dealing with the paperwork (the ‘back office’).

The trading activities are organized into desks: groups of traders workingwith a particular type of asset. The Kerviel story takes place in SocGen’s DeltaOne desk in Paris. Delta One trading refers to buying and selling straightforwardderivatives that do not involve any options. Options are derivatives which give‘the right but not the opportunity’ to make a purchase or sale. The trading ofoptions gives a return that depends non-linearly on whatever is the underlyingsecurity (we explain more about this in Chapter 9), but trading activities for aDelta One desk are simpler than this – the returns just depend directly on whathappens to the underlying security. In fact, the delta in the terminology refersto the first derivative of the return as a function of the underlying security, and‘Delta One’ is shorthand for ‘delta equals one,’ implying this direct relationship.

For example, a trade might involve buying a future on the DAX, which isthe main index for the German stock market and comprises the 30 largest andmost actively traded German companies. Futures can be purchased in relationto different dates (the end of each quarter) and are essentially a prediction ofwhat the index will be at that date. One can also buy futures in the individualstocks that make up the index and by creating a portfolio of these futures inthe proportions given by the weights in the DAX index, one would mimic thebehavior of the future for the index as a whole. However, over time the weights inthe DAX index are updated (in an automatic way based on market capitalization),

14 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

so holding the portfolio of futures on individual stocks would lead to a smalldivergence from the DAX future over a period of time.

The original purpose of a Delta One trading desk is to carry out trades for thebank’s clients, but around that purpose has grown up a large amount of proprietarytrading where the bank intends to make money on its own account. One approachis for a trader to make a bet on the convergence of two prices that (in thetrader’s view) should be closer than they are. If the current price of portfolio Ais greater than that of portfolio B and the two prices will come back togetherbefore long, then there will be an opportunity to profit by buying B and sellingA, and then reversing this transaction when the prices move closer together.Since both portfolios are made up of derivatives, the ‘buying’ and ‘selling’ hereneed not involve ownership of the underlying securities, just financial contractsbased on their prices. This type of trading, which intends to take advantage ofa mis-pricing in the market, is called an arbitrage trade, and since trades of onesort are offset by trades in the opposite direction, the risk involved should, intheory, be very low.

Many of these trading activities take advantage of quite small opportunitiesfor profit (in percentage terms) and therefore, in order to make it worthwhile,they require large sums of money to be involved. Kerviel was supposed to actas an arbitrageur, looking for small differences in price between different stockindex futures. In theory this means that trades in one direction are offset bybalancing trades in the other direction. But Kerviel was making fictitious trades:reporting trades that did not occur. This enabled him to hold one half of thecombined position but not the other. The result of the fictitious trade is to changean arbitrage opportunity with large nominal value but relatively small risk intoa simple (very large) bet on the movement of the futures price.

When Kerviel started on this process in 2006 things went reasonably well–hisbets came off and the bank profited. Traders are allowed to make some speculativetrades of this sort, but there is a strict limit on the amount of risk they takeon: Kerviel breached those limits repeatedly (and spectacularly). Over time theamounts involved in these speculations became greater and greater, and thingsstill went well. During 2007 there were some ups and downs in the way thatthese bets turned out, but by the end of the year Kerviel was well ahead. He hasclaimed that his speculation made 1.5 billion Euros in profits for SocGen during2007. None of this money made its way to him personally; he would only haveprofited through earning a large bonus that year.

In January 2008, however, his good fortune was reversed when some largebets went very wrong. The senior managers at the bank finally discovered whatwas happening on January 18th 2008. There were enormous open positions andSocGen decided that it had no option but to close off those positions and takethe losses, whatever these turned out to be. The timing was bad and the marketwas in any case tumbling; the net result was that SocGen lost 4.9 billion Euros.The news appeared on January 24th. The sums of money involved are enormousand a smaller bank would certainly have been bankrupted by these losses, butSocGen is very large and some other parts of its operation had been going well.

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 15

Nevertheless, the bank was forced into seeking an additional 5.5 billion Euros innew capital as a result of the losses.

Banks such as SocGen have elaborate mechanisms to ensure that they donot fall into this kind of situation. Outstanding positions are checked on a dailybasis, but each evening Kerviel, working late into the night, would book offsettingfictitious transactions, without any counterparties, and in this way ensure that hisopen positions looked as if they were appropriately hedged. Investigations afterthe event revealed more than a thousand fake trades; there is no doubt that theseshould have been picked up.

Kerviel, who was 31 when the scandal broke, was tried in June 2010. Heacknowledged what he had done in booking fake trades, but he argued that hissuperiors had been aware of what he was doing and had deliberately turned ablind eye. He said ‘It wasn’t me who invented these techniques – others didit, too.’ Finally, in October 2010, Kerviel was found guilty of breach of trust,forging documents and entering false data into computers; he was sentencedto three years in prison and ordered to repay SocGen’s entire trading loss of4.9 billion Euros. The judge held Kerviel solely responsible for the loss and saidthat his crimes had threatened the bank’s existence. The case came to appealin October 2012 and the original verdict was upheld. There is, of course, nopossibility of Kerviel ever repaying this vast sum, but SocGen’s lawyers havesaid that they will pursue him for any earnings he makes by selling his story.

1.7.1 What went wrong?

There is no doubt that what happened at SocGen came about because of a com-bination of factors. First there was Kerviel himself, who had some knowledgeof the risk management practices of the middle office through previously havingworked in this area. It seems that he kept some access appropriate to this, evenwhen he became a trader. This is exactly what happened with Nick Leeson atBarings – another famous example of a trader causing enormous losses at a bank.Kerviel was someone whose whole world was the trading room and, over thecourse of a year or so, he was drawn into making larger and larger bets withthe company’s money. There remains a mystery about what might have been hismotivation. In his appeal he offered no real explanation, simply describing hisactions as ‘moronic’, but maintaining that he was someone trying ‘to do his jobas well as possible, to make money for the bank’.

A second factor was the immediate supervision at the Delta One desk.Whether or not one accepts Kerviel’s claims that his bosses knew what wasgoing on, they certainly should have known and done something about it. It ishard at this point to determine what is negligence and what is tacit endorsement.Eric Cordelle, who was Kerviel’s direct superior, was only appointed head ofthe Delta One desk in April 2007, and did not have any trading experience. Hewas sacked for incompetence immediately after the fraud was discovered. Heclaims that during this period his team was seriously understaffed and he hadinsufficient time to look closely at the activities of individual traders.

16 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

A third important factor is the general approach to risk management beingtaken at SocGen in this period. It is easy to take a relaxed attitude to the riskof losses when everything seems to be going well. During 2007 there was anenormous increase in trading activity on the Delta One desk and large profitswere being made. The internal reports produced by SocGen following the scandalwere clear that there had been major deficiencies in the monitoring of risks by thedesk. The report by PriceWaterhouseCoopers on the fraud stated that: ‘The surgein Delta One trading volumes and profits was accompanied by the emergenceof unauthorized practices, with limits regularly exceeded and results smoothedor transferred between traders.’ Moreover, ‘there was a lack of an appropriateawareness of the risk of fraud.’

In fact there were several things which should have alerted the company toa problem:

• there was a huge jump in earnings for Kerviel’s desk in 2007;

• there were questions which were asked about Kerviel’s trades from Eurex,the German derivatives exchange, who were concerned about the hugepositions that Kerviel had built up;

• there was an unusually high level of cash flow associated with Kerviel’strading;

• Kerviel did not take a vacation for more than a few days at a time – despitea policy enforcing annual leave;

• there was a breach of Kerviel’s market risk limit on one position.

We can draw some important general lessons from this case. I list five ofthese below.

1. Company culture is more important than the procedures. The organiza-tional culture in SocGen gave precedence to the money-making side ofthe business (trading) over the risk management side (middle office), andthis is very common. Whether or not procedures are followed carefullywill always depend on cultural factors, and the wrong sort of risk cultureis one of the biggest factors leading to firms making really disastrousdecisions.

2. Good times breed risky behavior. In the SocGen case the fact that Kerviel’spart of the operation was doing well made it easy to be lax in the carewith which procedures were carried out. It may be true that the reverse ofthis statement is also true: in bad times taking risks may seem the onlyway through, but whether wise or not these are at least a conscious choice.Risks that managers enter into unconsciously seem to generate the largestdisasters.

3. Companies often fail to learn from experience. One example occurs whenmanagers ignore risks in similar companies, such as we see in the uncanny

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 17

resemblance between SocGen and Barings. But it can also be surprisinglyhard to learn from our own mistakes in a corporate setting. Often a scape-goat is found and moved on, without a close look at what happened andwhy. Dwelling on mistakes is a difficult thing to do and will inevitablybe perceived as threatening, and perhaps that is why a careful analysis ofbad outcomes is often ducked.

4. Controls need to be acted upon. On many occasions risks have been con-sidered and controls put in place to avoid them. The problem occurs whenthe controls that are in place are ignored in practice. SocGen had a clearpolicy on taking leave (as is standard in the industry) but failed to actupon it.

5. There must be adequate management oversight. Inadequate supervision isa key ingredient in poor operational risk management. In the SocGen case,Kerviel’s supervisor had inadequate experience and failed to do his job.More generally, risks will escalate when a single person or a small groupcan make decisions that end with large losses, either through fraud or sim-ple error. Companies need to have systems that avoid this through havingeffective oversight of individuals by managers, who need to supervise theiremployees sufficiently closely to ensure that individuals do what they aresupposed to do.

This book is mostly concerned with the quantitative tools that managers canuse in order to deal with risk and uncertainty. It is impossible to put into a singlebook everything that a manager might need to know about risk. In fact, the mostimportant aspects of risk management in practice are things that managers learnthrough experience better than they learn in an MBA class. But paying attentionto the five key observations above will be worthwhile for anyone involved inrisk management, and may end up being more important than all the quantitativemethods we are going to explore later in this book.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the culture within an organization:this will determine how carefully risks are considered; how reflective managersare about risk issues; and whether or not risk policies are followed in practice.A culture that is not frightened by risk (where employees are prepared todiscuss risk openly and consider the appropriate level of risk) is more likelyto avoid disasters than a culture that is paranoid about risk (where employees areuncomfortable in admitting that risks have been not been eliminated entirely).It seems that when we are frightened of risk we are more likely to ignore it, orhide it, than to take steps to reduce it.

Notes

This chapter is rather different than the rest of the book: besides setting the scenefor what follows, it also avoids doing much in the way of quantification. I havetried to distill some important lessons rather than give a set of models to be

18 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

used. I have found the book by Douglas Hubbard one of the best resources forunderstanding the basics of risk management applied in a broad business context.His book covers not only some of the material in this chapter but also has usefulthings to say about a number of topics we cover in later chapters (such as thequestion of how risky decisions are actually made, which we cover in Chapter 6).

A good summary of approaches which can be used to generate scenariosand think about causal chains as well as the business responses can be found inMiller and Waller (2003). The discussion on why we need to think differentlyabout safety issues is taken from the influential book by John Adams, who is aparticular expert on road safety.

The material on the Societe Generale fraud has been drawn from a number ofnewspaper articles: Societe Generale loses $7 billion in trading fraud, New YorkTimes, January 24, 2008; Bank Outlines How Trader Hid His Activities, NewYork Times, January 28, 2008; A Societe Generale Trader Remains a Mysteryas His Criminal Trial Ends, New York Times, June 25, 2010.; Rogue TraderJerome Kerviel ‘I Was Merely a Small Cog in the Machine’ Der Spiegel Online,November 16, 2010.

We have said rather little about company culture and its bearing on risk, butthis is by no means a commentary on the importance of this aspect of risk, whichprobably deserves a whole book to itself (some references on this are Bozemanand Kingsley, 1998; Flin et al., 2000; Jeffcot et al., 2006 as well as the papersin the book edited by Hutter and Power, 2005).

References

Adams, J. (1995) Risk . UCL Press.

Bozeman, B. and Kingsley, G. (1998) Risk Culture in Public and Private Organizations.Public Administration Review , 58, 109–118.

Flin, R., Mearns, K., O’Connor, P. and Bryden, R. (2000) Measuring safety climate:identifying the common features. Safety Science, 34, 177–192.

Hubbard, D. (2009) The Failure of Risk Management . John Wiley & Sons.

Hutter, B. and Power, M. (2005) Organizational Encounters with Risk . Cambridge Uni-versity Press.

Jeffcott, S., Pidgeon, N., Weyman, A. and Walls, J. (2006) Risk, trust, and safety culturein UK train operating companies. Risk Analysis , 26, 1105–1121.

Miller, K. and Waller, G. (2003) Scenarios, real options and integrated risk management.Long Range Planning , 36, 93–107.

Power, M. (2004) The risk management of everything. Journal of Risk Finance, 5, 58–65

Rice, J. and Franks, S. (2010) Risk Management: The agile enterprise. Analytics Magazine,INFORMS.

Ritchie, B. and Brindley, C. (2007) Supply chain risk management and performance.International Journal of Operations & Production Management , 27, 303–322.

Stulz, R. (2009) Six ways companies mismanage risk. Harvard Business Review , 87 (3),86–94

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 19

Exercises

1.1 Supply risk for valves

DynoRam makes hydraulic rams for the mining industry in Australia. Itobtains a valve component from a supplier called Sytoc in Singapore. Thevalves cost 250 Singapore dollars each and the company uses between 450and 500 of these each year. There are minor differences between valves,with a total of 25 different types being used by DynoRam. Sytoc deliversthe valves by air freight, typically about 48 hours after the order is placed.Deliveries take place up to 10 times a month depending on the productionschedule at DynoRam. Because of the size of the order, Sytoc has agreeda low price on condition that a minimum of 30 valves are ordered eachmonth. On the 10th of each month (or the next working day) DynoRampays in advance for the minimum of 30 valves to be used during that monthand also pays for any additional valves (above 30) used during the previousmonth.

(a) Give one example of market risk, credit risk, operational risk andbusiness risk that could apply for DynoRam in relation to the Sytocarrangement.

(b) For each of the risks identified in part (a) suggest a management actionwhich would have the effect either of reducing the probability of therisk event or minimizing the adverse consequences.

1.2 Connaught

The following is an excerpt from a newspaper report of July 21, 2010appearing in the UK Daily Telegraph.

‘Troubled housing group Connaught has been driven deeper intocrisis after it discovered a senior executive sold hundreds ofthousands of pounds worth of shares ahead of last month’s shockprofit warning.

The company which lost more than 60% of its value in just threetrading days in June, and saw its chief executive and financedirector resign, has launched an internal investigation into thebreach of city rules. . . Selling shares with insider informationwhen a company is about to disclose a price-sensitive statementis a clear breach of FSA rules.

Connaught, which specializes in repairing and maintaining lowcost (government owned) housing, has fallen a total of 68%since it gave a warning that a number of public sector clientshad postponed capital expenditure, which would result in an80 million pound fall in expected revenue this year.

20 BUSINESS RISK MANAGEMENT

The group said that it had been hit by deferred local authoritycontracts which would knock 13m pounds off this year’s profitsand 16m pounds from next year’s. It also scaled back the sizeof its order book from the 2.9 billion pounds it said it was worthin April to 2.5 billion.

The profit warning also sparked renewed concerns about howConnaught accounts for its long-term repair and maintenancecontracts. Concerns first surfaced late last year with city analystsquestioning whether the company was being prudent when rec-ognizing the revenue from, and costs of, its long term contracts.

The company vehemently defended its accounting practices atthe time and continues to do so. Chairman Sir Roy Gardner hastried to steady the company since his arrival earlier this year.’

(a) How would you describe the ‘profits warning’ risk event: is it broughtabout by market risk, credit risk, operational risk or business risk?

(b) From the newspaper report can you make any deductions about riskmanagement strategies the management of the company could havetaken in advance of this in order to reduce the loss to shareholders?

1.3 Bad news stories

Go through the business section of a newspaper and find a ‘bad news’ story,where a company has lost money.

(a) Can you identify the type of risk event involved: market risk, creditrisk, operational risk or business risk?

(b) Look at the report with the aim of understanding the risk managementissues in relation to what happened. Was there a failure to anticipatethe risk event? Or a failure in the responses to the event?

1.4 Product form for heat map

Suppose that the risk level is calculated as the expected loss and thatthe likelihoods are converted into probabilities over a 20-year period asfollows: ‘very likely’ = 0.9; ‘likely’ = 0.7; ‘moderate’ = 0.4; ‘unlikely’= 0.2; and ‘rare’ = 0.1. Find a set of dollar losses associated with the fivedifferent magnitudes of impact such that the expected losses are ordered inthe right way for Figure 1.1: in other words, so that the expected losses fora risk level of low are always lower than the expected losses for a risk levelof medium, and these are lower than the expected losses for a risk level ofhigh, which in turn are lower than the expected losses for a risk level ofextreme. You should set the lowest level of loss (‘insignificant’) as $10 000.

WHAT IS RISK MANAGEMENT? 21

1.5 Publication of NHS reform risk register

Risk registers may take various forms, but the information they contain cansometimes be extremely sensitive. In 2012 the UK government discussedwhether or not to release the full risk register that had been created for thehighly controversial reform of the National Health Service. The health sec-retary, Andrew Lansley, told parliament in May 2012 that only an editedversion of this document would be made available, on the principle thatcivil servants should be able to use ‘direct language and frank assessments’when giving advice to ministers. Lansley argued that if this advice wereto be released routinely then ‘future risk registers [would] become ano-dyne documents of little use.’ The net result would be that ‘Potential riskswould be more likely to develop without adequate mitigation. That wouldbe detrimental to good government and very much against the public inter-est.’ Using this example as an illustration, discuss whether there is a tensionbetween realistic assessment of risk and the openness that may be implicitin a risk register.