iGreenLover 2014 catalogue : green products that outshine, outlast, outperform

What I Create Will Outlast Time — by Rafik Schami

Transcript of What I Create Will Outlast Time — by Rafik Schami

What I CreateWill Outlast Time

—The Story of the

Beauty of Arabic Script

Celebrating the Publication of

The Calligrapher’s

Secret

by Raf ik Schami

CONTENTS

MUSIC FOR THE EYESAn Essay on Calligraphy by Ra�k Schami

THE CALLIGRAPHER’S SECRETAn preview of the just published novel

PRAISE FOR RAFIK SCHAMI

— 7 —

— 40 —

— 46 —

The Calligrapher’s Secret is published

in English by

INTERLINK BOOKS

An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc.

www.interlinkbooks.com

© Rafik Schami 2010

English translation © Anthea Bell 2010

Calligraphy © Ismat Amiralaiwww.salam-verlag.de

He is a prophet of the art of script, Godplaced calligraphy in his hand just as hetaught the bees to build the hexagonal

cells of their honeycombs

Abu Haiyan al-Tauhidi Encylopaedist and Sufi scholar, on Ibn Muqla

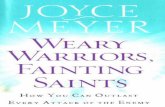

‘What I Create Will Outlast Time’

by Rafik Schami

Calligraphy by Ismat Amiralai

Translated by Anthea Bell

The Story of the Beauty of Arabic Script

If anyone can be called ‘the Leonardo da Vinci of Arabic calligraphy’ it is Abu Ali Muhammad bin Hassan bin Muqla, known simply as ‘Ibn Muqla’, born in the slums of Baghdad in 885. (Ibn Muqla’s name is a curiosity in itself: Muqla, a poetic word for ‘eye’, was the affec-tionate nickname given to his mother by her father, who loved this particular daughter. When she married a poor calligrapher, the fam-ily was called not after him or his clan, but after her – a rare occur-rence in Arab culture, then as now.) Ibn Muqla’s father, grandfather and brother, as well as his own children and grandchildren, were all calligraphers; and Ibn Muqla was the most famous of them all. He learned the art of calligraphy when young, and at the age of sixteen he became the star pupil of the famous calligrapher Ibn Furat, who later rose to the rank of vizier in the ‘Abbasid Empire. Ibn Muq-la’s former teacher then found him a post in the state civil service as a tax gatherer for the caliph, and the young man grew very rich indeed. Though the ‘Abbasid Empire was the most powerful civilisation in the world of its time, the golden age of the first nine caliphs already lay in the distant past. In Ibn Muqla’s lifetime, which spanned the end of the ninth century and the beginning of the tenth, Arab culture was very sophisticated. Baghdad produced more paper and books than the whole of Europe put together; there were more bookshops to be found in the city than in the rest of the world. Politically, however, the empire was visibly breaking up. Its peripheries, where local rulers (in Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, the Maghreb, Andalusia and elsewhere) were practically autonomous, were not the only regions affected: re-bellions reached the centre of power and shook it to its foundations. The rebels who made their way to Baghdad and Mecca were often Shi‘i Muslims, or drawn from the ranks of non-Arab peoples. They humiliated the Sunni caliph al-Muqtadir, repeatedly destroying his cities (e.g. Basra in 912 and 924, Mecca in 929).

9

First choose your travelling companian and later your route

10

The bureaucrats, the harem and the emirs who led the army and the police all gained more and more power in Baghdad at the expense of the caliph, who was not infrequently deposed and arrested, his prop-erty seized by his own party – only to be liberated by the other side and reinstated as the ‘new’ caliph. It was in this atmosphere that Ibn Muqla lived and worked. This greatest Arabic calligrapher of all time was an architect of script. He not only developed and improved several styles of writ-ing (among them Thuluth and Naskhi), but was also first to propose a theory of the dimensions of written characters, keeping them in harmony and symmetry with each other. His doctrine of proportion holds to this day, and can easily be used to check whether or not the proportions of a work of calligraphy are correct or not. The first letter in Arabic, alif, is a vertical stroke, and was chosen by Ibn Muqla as the criterion for all written characters. Since Ibn Muqla all calligraphers begin by choosing the length of alif as a measure in their script. The calculation is worked out by means of vertically placed diacritical marks – rhomboid ‘dots’, the size of which de-pends on the width of the pen as it is pressed down on the paper. All the other letters, whether horizontal or vertical, are adjusted to the size worked out by Ibn Muqla and determined by a given number of diacritics. In addition, the curves of many letters lie along a circle with a diameter corresponding to the length of the character alif. This technique is sometimes referred to as ‘proportional script’, be-cause all the letters relate to the size of alif and the width of the pen (that is to say, of the dot it makes). Keeping to these proportions is analogous to maintaining the rhythm of a musical composition. It introduces harmony to the script, making ‘music for the eye’. After years of practice, every mas-ter calligrapher does it automatically. However, the dots always allow

11

for a quick check as to whether or not the proportions are correct. Ibn Muqla was a gifted mathematician, calligraphic scholar and natural scientist, and the author of some remarkably straightforward and candid poems. He also studied the works of theologians and atheists – writers such as Ibn al-Rawandi, Ibn al-Muqaffa’, al-Rasi and al-Farabi. He was inspired most of all by the polymath scholar al-Jahiz; unlike al-Jahiz, however, Ibn Muqla enjoyed being close to the rulers of his time – whereas al-Jahiz could not endure more than three days at the court of Caliph al-Ma’mun, the great patron of sci-ence and literature who reigned from 813–33.

Ibn Muqla eventually became First Vizier – the equivalent of a prime minister today – under the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth ‘Ab-basid caliphs (beginning with al-Muqtadir). But proximity to them, which he sought again and again, would be his undoing. At the time Baghdad was the capital of a grand empire, and the cen-tre of both secular and religious Islamic power. Conservative Muslim scholars, however, were hostile to any kind of reform. They regarded

12

Arabic script as sacred: the expression of the word of God set down in the Qur’an. Ibn Muqla, of course, knew it was not of divine origin. Fascinated by its beauty, he nevertheless also recognised its weak-nesses. (Many calligraphic scholars and translators of his day, for ex-ample, had criticised the absence of letters in Arabic that could allow them to reproduce sounds from other languages.) Quite early on, Ibn Muqla began wondering how he could introduce cautious reform into the alphabet, the source of the script itself. He experimented, made notes and waited for a suitable moment. Arabic script had been reformed several times already, a fact that was known to Ibn Muqla. The most radical change had been introduced in Baghdad over 150 years before his birth. Until then the script had contained no diacritics, and many of the characters resembled each other. Uncertainty, misunderstanding and misinterpretation were thus always likely to intrude into the reading process, even when scholars were reading aloud. Several minor reforms were attempted, but the greatest of them came at the beginning of the eighth century. Diacritics had been added, in the form of one, two or three dots, to fifteen of the letters (over half the Arabic alphabet), situated above or below the character. Mistakes in reading could then be almost elimi-nated. The Umayyad caliph, ‘Abd al-Malik bin Marwan (685–705), and al-Hajjaj, the bloodthirsty governor of his eastern provinces, had stifled all the conservative voices against reform. The caliph had the Qur’an recopied in the reformed script, after that anyone could read the holy book without making mistakes. It was not only religious texts that gained greater clarity. Ara-bic poetry and science, as well as the everyday use of the script, had also become clearer and more precise as a result. Without the power of the caliph behind it, however, such a step could never have been taken, and Ibn Muqla knew that. He, too, needed the strong hand of

13

an enlightened and farsighted caliph to push through his own, now-overdue reforms. Ibn Muqla loved calligraphic script like his own child. He gave all he had in its service – and in the end he lost everything. Were all his efforts aimed simply at gaining power, as his enemies claimed? Certainly, they forged hostile accounts of his activities, filling whole books with their flimsy reasoning; the answer was no. Ibn Muqla had already achieved so much before introducing the radical steps lead-ing to reform and to his personal ruin. Ibn Muqla was the tutor of the twentieth ‘Abbasid caliph, al-Radi Billah, teaching him philosophy, mathematics and language; he was to him what Aristotle had been to Alexander the Great, though this caliph lacked the stature of the Macedonian conqueror, to say the least. At the height of his power, Ibn Muqla had a legendary palace built in Baghdad. He had prophetic words carved into the great stone blocks of the interior of the garden wall: ‘What I create will outlast time.’ His power and wealth caused many people to envy him, which would not have mattered had al-Radi been a man of strong character or authority. Ibn Muqla would also have been spared had the Islamic scholars of his time not turned against him, issuing fatwas to justify the penalties inflicted on him. Their hostility had increased over the years, and they observed everything the First Vizier did with suspi-cion. Passionate about animals, Ibn Muqla’s converted his huge palace garden into a zoo, where different animals could move freely about in separate enclosures. He had a far-flung network of correspond-ents who sent him news from all over the empire by pigeon post; to give the birds the illusion of freedom, he had the zoo covered with a silken net stretched high above the garden. A team of keepers and veterinarians looked after the animals. Ibn Muqla attempted to un-

14

derstand Creation through study of the animal kingdom; his staff conducted research, with some degree of success, in cross-breeding birds, dogs, cats, sheep, goats, donkeys and horses. Many of these experiments also led to the birth of creatures with deformities, how-ever, and aroused interest in the caliph’s court but also hatred and contempt. Ordinary people remained remote from all the debates and experiments, of course, hidden as they were behind the thick walls of the palaces of Baghdad. Progress in natural science encouraged Ibn Muqla to take a differ-ent kind of step, which could have brought him worldwide renown: the extension of Arabic and its script by cross-breaeding it with oth-er languages. He had studied Persian, Arabic, Aramaic, Turkish and Greek, as well as the changes undergone by Arabic from its begin-nings to his own time. Taking care in the course of his studies he was able to invent a new Arabic alphabet that, with only twenty-five letters, could express words in all the languages then known. Al-Radi Billah had a great liking for his tutor and First Vizier, but all the same Ibn Muqla overestimated the caliph’s ability to support his attempts to reform the written language. Al-Radi was twenty-four years old, an open-minded man who wrote poetry himself and loved wine and women. Like all the later ‘Abbasid caliphs, however, his say in the affairs of his court steadily diminished. Palace bureau-crats, princes, the caliph’s wives and high-ranking officers of state all engaged in intrigues, ensuring that no reformer could stay near the caliph for too long. Ibn Muqla was, by then, in his late forties. He realised that the caliphate was rotting from the head down, and feared that he would not be able to put his revolutionary plans into practice. Baghdad had become a place of unrest, revolution and plotting. Ibn Muqla himself had a proud nature and a hot temper, and was often irritable,

15

Food, humour and patience are the camels that will lead you through all deserts

16

impatient and brusque with court officials, making himself more en-emies than friends among those close to the caliph. Yet despite the conspiracies against him, the fact that he had become First Vizier to the young caliph strengthened Ibn Muqla’s belief in his own powers – and left him isolated in the ruler’s palace. Loyal friends, rightly anxious on his behalf, advised him to leave the palace and enjoy his fame as a brilliant calligrapher; but Ibn Muqla wanted to pursue his ambitious plan for the Arabic alphabet, and needed the caliph’s support against the mosques. He knew that the mere idea of changing Arabic script was considered a mortal sin. Previous caliphs had kept as many as 4,000 women and eunuchs in their palaces to minister to their pleasure, and quite often liked wine better than theology, but they were unyielding when it came to religion. Famous philosophers and poets had been lashed or bar-barically executed for suggesting the least reform to the structure of government or expressing the faintest doubt in the Qur’an. The caliphs did not scruple to consider themselves the ‘shadow of God on earth’, and their caliphates the perfect expression of divine rule. They and (to a greater degree) their administrators were implac-able at the suggestion that any change could be introduced whatso-ever to Islam. Ibn Muqla’s revolutionary reform was double-pronged. His im-mediate wish was to give the Arabic script such a clear and straight-forward form that reading it would present no further problems. His second, long-term and more important objective was to re-create the alphabet to encompass all the sounds in the world, and to endow its characters with even greater clarity. He was unaware that with his first aim, he was supporting the ruling Sunnis in their struggle with the Shi‘is. Several Shi‘i groups – the Ismailis, for instance – had always regarded the Qur’an as a book written on several levels, ca-

17

pable of supporting various interpretations. Certain extremists went so far as to claim that what the common people understood of the Qur’an was merely al-saher: the surface, the husk, which concealed a more important and complex kernel, batin. (They were, therefore, known as the ‘Batinis’.) According to their doctrine, every word in the Qur’an had a double meaning. Sunni doctrine claimed the dia-metrical opposite: there could be no double meanings in the language of God. The court in Baghdad was Sunni. The caliph and his advisors, court philosophers and theologians characterised their campaign against the Shi‘is as the struggle of God’s chosen ruler against apostates and unbelievers. They were delighted that Ibn Muqla had developed a precise system for the dimensions of written characters, and a simple, beautiful and flexible script – Naskhi – that copyists could now use to write out the Qur’an quickly, clearly and without flourishes. (The name Naskhi derives from the verb ‘to copy’, and to this day it is the script used most often for printing books.) Ibn Muqla had become the best weapon in the Sunni arsenal against Shi‘i opposition. The caliph and his theologians, however, did not realise that Ibn Muqla wanted to further and more radically reform the writing system. Caliph al-Radi loved his First Vizier, and praised him publicly, but when Ibn Muqla confided a detail about the new alphabet he had conceived, the caliph was shocked. Ibn Muqla’s antagonists al-Mu-zaffar and Ibn Ra’iq had already been stirring up the caliph’s feelings against the calligrapher; he cautioned his vizier that his rivals were now moving against him, but Ibn Muqla interpreted this warning as a hint from an ally. He promised to take more care, but stuck to his plan, and began to assemble groups of like-minded people. Some scholars and well-known translators shared his views on the necessity for radical reform of the Arabic language and script, but knew the

18

danger of adopting such an attitude outright and kept a low profile. Ibn Muqla scorned the danger. He felt certain that he had al-Radi’s sympathies. Learning of his ideas, Ibn Muqla’s adversaries informed the caliph and drew a direct connection between them and the animal experi-ments the vizier had been conducting – the only aim of which, as they saw it, was to mock God by making Ibn Muqla figure as a crea-tor in his own right. And now this man also wanted to change the holy language of the Qur’an! The young caliph told Ibn Muqla to abandon his plans. Ibn Muqla, who was very devout at heart, could not see that his re-forms entailed any deviation from the Qur’an, and assured the caliph that he would sooner die than doubt a word of Holy Scripture. In fact, he said, the simplification and extension of Arabic script would give the language, and thus the Qur’an, yet wider distribution. When the two friends parted, each held the erroneous and dangerous belief that he had convinced the other. Ibn Muqla underestimated his enemies. At first, al-Radi did not reject the idea of reform. But the clerics had threatened to rebel against him in the name of remaining true to Islam, should he agree to Ibn Muqla’s vision. Al-Radi knew what that meant: he had watched an angry mob murder his father, seen his uncle al-Qahir deposed and arrested and only just escaped an assas-sination attempt on his own life. Now Something happens that shows the calligrapher in a curious light. On his way to see the caliph, Ibn Muqla was attacked in a palace cor-ridor by slaves of al-Muzaffar and Ibn Ra’iq and dragged away. The conspirators tortured him, and told the caliph that the calligrapher had been plotting against him, writing appeals for his overthrow. The furious al-Radi ordered Ibn Muqla’s arrest without questioning him

19

personally or even seeing him. He lacked the courage to punish his vizier in person, delegating the task to his emirs and court officials, never guessing that they were the leaders of a plot against Ibn Muqla, They had the former vizier lashed, but he refused to tell them where he had hidden his written-out new alphabet. In return his right hand was cut off and his property seized. Soon his palace was in flames. It is said that everything in it burned, but for the section of the interior wall that bore the word ‘time’. What the fire did not consume was stolen by the hungry people of Baghdad. The conspirators announced that Ibn Muqla had been plotting against the caliph. His friends were too afraid to demonstrate any support for him, and made no attempts to rehabilitate him. One pal-ace historian refuted the false accusations against Ibn Muqla, writing that he was not, as usual in such cases, executed; rather, the caliph sent his personal physician Hassan bin Thabet to tend the calligrapher’s wounds. A few days later the caliph even invited Ibn Muqla to eat with him, and made him vizier again. Ibn Muqla wrote a poem about his disappointment:

Men are friends to fortune. When it left me for half a day, they fled in fear. Oh men, return, for fortune is true to me once more.

He lamented his mutilation for the rest of his life. ‘My hand was chopped off like a thief’s, the hand with which I twice copied the Qur’an.’ Ibn Muqla was now fifty years old, and despite everything he had no intention of giving up. He devised a bandage enabling him to

20

fasten the reed he used as a pen to the stump of his wrist, and was thus able to write calligraphy again, if not as beautifully as before. He founded the first great school for calligraphers with the aim of pass-ing on his knowledge, and would gather his most gifted students in a circle of initiates who would understand his reforms, remember them and pass them on if anything were to happen to him. He hoped to defeat death itself by implanting the secret of his script in the hearts of young calligraphers. But at the same time, he failed to see that he was walking into another trap set by his enemies, who misrepresented his plans for the school as further evidence of a plot against the caliph. Al-Radi was angry that Ibn Muqla would not listen to him, and ordered Ibn Ra’iq to hold the calligrapher prisoner in a house far from the city, to ensure that he could not dictate his secrets to anyone again. The calligrapher was to live there at the expense of the palace until the end of his days. Ibn Ra’iq had Ibn Muqla’s tongue cut out, and flung him into a prison on the outskirts of the desert to endure isolation and misery. Protests from poets and scholars did no good. Ibn Ra’iq had already seized power in the palace. Ibn Muqla died July 940, still famous throughout the Islamic world. His renown endures today. The greatest poets of his epoch, men such as Ibn Rumi and al-Sauli, made moving speeches at his graveside. If he had indeed been in-volved in a conspiracy against the caliph or the Qur’an as his enemies claimed, no poets would have dared to praise him, let alone show that they mourned him; for the poets and scholars of the time worked at the caliph’s court and lived by his grace and favour. ‘What I create will outlast time,’ Ibn Muqla’s famous declaration, testifies to the vision of a man who knew that the rules he created for Arabic calligraphy would endure as long as the script itself.

21

I taught him to compose and his first verse was written against me

22

Music for the Eyes: A Short Introduction to Arabic Script

Arabic script is used by over 300 million Arabs for whom Arabic is a mother tongue, and by more than a billion Muslims living in Paki-stan, Iran and other countries. The invention of the alphabet by the Phoenicians changed the world radically. Like the wheel, it sped up the development of human culture. With twenty-two letters, the Phoenicians could reproduce phonemes, the sounds of human speech. Objective statements and ab-stract ideas could thus be presented and recorded much more quickly and precisely than any other kinds of written characters. Many scripts such as Greek and Aramaic developed from the Phoe-nician alphabet. Aramaic spread from North Africa across the Mid-dle East and into India. In turn, Hebrew and Arabic developed from Aramaic. Linguists are now certain that Arabic script reached its final form by way of an interim stage, Nabataean Arabic. The seventh- to twelfth-century Arab conquests – in less than a hundred years the empire of the Umayyads expanded from Asia, across the Middle East and Africa to Spain – also widely distributed Arabic script. Transla-tion of the Qur’an was not allowed, moreover, so believers had to learn Arabic in order to pray. Persian, Ottoman Turkish and Urdu also came under the influence of Arabic script, as did, sometimes, even Spanish, Portuguese and Swahili. The Arabic language itself, however, spread more slowly, as regions that had resisted the con-querors retained their own languages and religions. Arabic is written from right to left. The alphabet has twenty-five consonants and three long vowels: A, I and U. Formerly, the short vowels were written above and below the letters, making possible a perfect reading of the text. Modern script has abandoned these nu-

23

A house without books is a house without a soul

24

ances, however. Individual letters are always cursive in Arabic script, both in hand-writing and in print. Every letter has four forms, depending on whether it stands at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of a word, or on its own. The Roman alphabet, by comparison, has only two forms, majuscule and minuscule. There is an additional difficulty in that twenty-two letters in Arabic can be joined up to others on both sides, but six letters can be linked only to the left. If they occur in the middle of a word, the letter to their left is written as though it stood at the beginning of a word. Ligatures (the links joining the let-ters) play an important part in the design of Arabic script. Prior to the Islamic period, the desert-dwelling Arabs had nothing in the way of the visual arts as striking as Greek or Roman painting and sculpture; but the desert lets the eyes rest and loosens the tongue, and the Arabs did have one of the finest traditions of poetry in the world. Islam increased the importance of the word and its aesthetic expression in calligraphy, initially for sacred purposes. Later on, Ara-bic script was used decoratively in or on palaces, vessels, jewellery, books and other luxury goods. Yet it has always remained attached to the sacred. Mosques, which of course contain no images or statues, are adorned with inscriptions as though they were huge books in themselves. Thus Arabic calligraphy became the outstanding visual art form in the Islamic world and the importance of the Ottoman and Persian calligrapher was outstanding. If calligraphy was practised at first for purely religious reasons – to give aesthetically pleasing and legible form to the sacred texts and heighten the spiritual atmosphere of places of prayer through the beauty, rhythm, reflection, and the variety it displays even in its unity – it later went further and developed into an art form in its own

25

right, independent of content but enhancing the understanding of the texts at the same time. The art of calligraphy was greatly encouraged in Baghdad. Ibn Muqla and his successors perfected Arabic script over three centuries. Later, the calligraphers of Istanbul took up that role, practising and extending calligraphy further still. Calligraphy is subject to strict laws dating back to Ibn Muqla, but a calligrapher may choose from several styles. Every script variation, in turn, contains countless opportuni-ties for reflection, repetition and style of ligature, so a calligrapher may shape it in accordance with his aesthetic ideals.

Script Styles

Various styles of writing have developed over the course of centuries. With the coming of the computer age, hundreds more have arisen, though no single significant trend can be discerned amongst that huge number. The following six classic styles remain canonical.

Kufi. Called after the Iraqi city al-Kufa, Kufi script had already at-tained perfection in the second half of the eighth century. This style has an angular appearance that gives it a religious aura, evoking min-arets. It is used to good effect in the architecture of mosques and palaces, but also in the design of everyday utensils. A popular variant of this style is ‘floral’ Kufi, in which plants and flowers emerge from the characters; the effect is decidedly ornamental, if more difficult to read. In another variant, ‘woven’ Kufi, only experts can decipher the text amidst the ornamentation. Thuluth. (The th is pronounced as in English, e.g. ‘the’; this style is also called Talat or, in Turkish, Sülüs.) Thuluth means ‘one-third’,

26

and once referred to the width of the tip of the reed pen used for writing it. The broadest pens had twenty-four hairs, the pen for Thu-luth script only eight. This style reached its prime between the sev-enth and tenth centuries, and was regarded as the touchstone of any calligrapher’s art. Thuluth is, therefore, known as ‘the mother of cal-ligraphy’. It is often used when printing particularly exquisite books and reli-gious texts, and for ornamenting and decorating mosques and official buildings.

Naskhi. Created by Ibn Muqla in the tenth century to facilitate the work of copying (Arabic: nasakha, to copy) and above all to make it easy to read text clearly. Today most books in Arabic use this style, which is elegant and clear. Riq’a. Developed from Ottoman calligraphies that aimed to achieve maximum simplicity, this script is small, compressed and free of or-namentation. It spread quickly, being especially suitable for hand-writing. Arabic newspaper headlines are often printed in this familiar style. Farsi (also known as Ta’liq and Nasta’liq). Farsi script is airy and elegant, with a lithe, dynamic and often diagonal line. The few points to which it rises are often rounded. Its horizontal characters are gen-erous and broad in extent, with the rhythm of the letters lending a peaceful note to the visual music of the script. Today this style is dominant in Iran. Diwani. This script was used in state chancelleries (diwan). Diwani is majestic, its characters often following the line of a circle with its

27

28

Die Schriftstile von oben nack unten:Thuluth, Nas-chi, Farsi, Rihani, Riqa’i, Diwani, Diwani Gali, Kufi

diameter equal to the height of the letter alif. Tughra. Now extinct, this script resembled a fingerprint and was reserved for Ottoman sultans, whose name and sometimes royal ep-ithets were integrated into its design. Later, religious sayings were written in Tughra, becoming icons. The writing did not follow the right-to-left rule but ran as the figure required. A curious story about the origin of this style has the fourteenth–fifteenth-century Mon-gol conqueror Timur Leng and Sultan Bayezid I at odds; as Timur could not write, he dictated a letter to Bayezid through his clerk, then authenticated it with his thumbprint. The sultan replied with a particularly complicated way of writing his name in a filigreed style – Tughra.

He the instructed his calligraphers to design this emblematic finger-print for him at once, demonstrating the high level of Ottoman civi-lisation to his enemy.

29

Tughra des osmanischen Sultans Mahmud II.

Music for the Eyes

There are considerable differences between Arabic and other written languages of the world using the Roman, Cyrillic, Hebrew, Greek, Korean and Chinese alphabets, and so on. Writing in these languages, for example, consists of various units divided from each other, and necessitates the regular raising and lowering of the pen. When the eyes read, they, too must learn to understand the repeated interrup-tions of the written line. Arabic characters, cursive, are linked together in handwriting and in printing. The words form a calligraphic river, and it is this quality that marks out the Arabic script as the perfect medium in which to make music for the eye – for just as the ear enjoys music, the eye can enjoy Arabic calligraphy, even without understanding the text.As the script is always written continuously, the length of the liga-tures is very important in the composition. Lengthening or abbre-viating these links is to the eye what lengthening or abbreviating a musical note is to the ear. The letter alif, a vertical stroke in Arabic, becomes a kind of bar line in the musical rhythm. However, as the size of the letter alif determines that of all other characters in ac-cordance with the doctrine of proportion, it too plays a part in the height and depth of the ‘music’ formed horizontally by the letters in every line. Also influencing the visual music is the variety in breadth, from very fine to generous, both in the letters themselves and in the ligatures at the top, bottom or centre of those letters. Extension along the horizontal, alternation between rounded and angular characters and between vertical and horizontal lines all have their effect on the melody of the script, evoking an atmosphere that is light, playful and cheerful, touchingly melancholy or heavy and dark.

30

Should a calligrapher wish to compose music carefully with the char-acters, the empty spaces between letters and words calls for yet great-er skill. The spaces in a work of calligraphy are moments of silence. Like Arab music, calligraphy returns to the repetition of certain ele-ments, not only promoting the dance of body and mind but also sug-gesting that we are rising from the earthly sphere, reaching toward other regions.As we can see from the papers left by Goethe, the great polymath practised writing Arabic script without ever having learned to read the language, especially at the time he was taking an interest in the Orient and writing his poems published as the West–Eastern Divan. Why is this, we may wonder?Goethe recognised that the form of Arabic script is a wonderful way of conveying the nature of Arab culture, even if those who do not read the language cannot understand the text. In his 1815 correspond-ence with Christian Schlosser, the nephew of a close friend, he wrote that in no language more than Arabic were ‘the mind, the word and the script so closely incorporated from the very beginning’. Goethe filled sheet after sheet with his Arabic writing exercises, as if to dis-cover from his ‘intellectually technical efforts’ how Arabs think and feel – as if to Orientalise himself, in fact. In these exercises he both saw the music of the script with his eyes and accompanied it, fasci-nated, with his hand. Surely deep within his mind, Goethe was listen-ing to the melody of Arabic script.

31

A Beautiful Alphabet with a Few Flaws

If you were to ask two Arabs how many letters there are in the Ara-bic alphabet, one would probably reply, with some embarrassment, ‘twenty-eight’, and the other – even more embarrassed – would like-ly contradict this answer: ‘No, I’m sure there are twenty-nine letters.’The uncertainty and imprecision of the answer might appear surpris-ing, for it is not as though the questioner were asking, say, how many Chinese symbols an educated Chinese person must master. Even in the first decade of the twenty-first century, these two figures alternate everywhere: in Arabic language or calligraphy manuals, on Internet discussion forums and in the minds and memory of Arabs. Where does this difference of opinion come from? The putative twenty-ninth letter consists of two letters, equivalent in the Roman alphabet to L and A. it is therefore not a letter but a word, meaning ‘no’ or ‘not’.

How, then, could millions of Arabs – amongst them literary schol-ars, philosophers, linguists, liberals, rebels, innovators and tradition-

32

The Arabic Alphabet.......

al purists, and some of whom spend months if not years discussing and debating the form of a poem or the right way to decline a verb, have overlooked the fact that their beloved alphabet is defective? The answer has to do with the history of this one character, and of Arab society. Many legends have accumulated around the alleged let-ter consisting of the L/A combination. According to the best-known anecdote, a companion of the Prophet asked him how many letters God gave Adam, and the Prophet replied: ‘Twenty-nine.’ His schol-arly friend courteously corrected him, saying that he himself had found only twenty-eight Arabic letters. The Prophet repeated that the answer was twenty-nine, whereupon his companion counted them again and said no, there were only twenty-eight. At that the Prophet, flushed with anger, told the man: ‘God gave Adam twenty-nine Ara-bic letters. Seventy thousand angels bore witness to it. And the twen-ty-ninth letter is LA.’ The Prophet’s companions knew he was wrong, and they were not alone: thousands of scholars and readers kept quiet about it for 1,300 years, teaching their children an alphabet contain-ing a superfluous letter that is not a letter at all. The Arabic language remained unreformed for the same length of time. Again and again, the brave called for reform, but their calls were lost in the desert air. The ossification of Arabic and its alphabet cannot merely be attrib-uted to religious fundamentalism, which sanctified the language and regarded any change to it as an attack on God and the Qur’an. It is more deeply rooted in the Arab clan system itself, which, though it was a brilliant means of coping with the hostile conditions of desert life and enabled Arabs to survive for millennia, could not tolerate change and proved to be a great obstacle to further development. The caliph was analogous to the head of a great clan, and lived in the capital; local rulers remained in their respective cities, where, in marked contrast to Europe at that time, advanced culture prevailed

33

as early as the seventh century. In Arab history (and in Asian history in general), therefore, the city was not the site of bourgeois rebel-lion, reform and dynamism, but the residence of the ruler and his philosophers, poets and scholars in the fields of religion, history and language. Nothing could be done there without the permission of the caliph, sultan or king. There were, of course, always rebels calling for reform, but they were exiled, persecuted or quite often executed. Some enlightened rulers (such as al-Ma’mun) made their palaces cen-tres of cultural progress – we have them to thank for developments in philosophy and natural science, as well as for some of the finest poetry in the world. But no caliph was a guarantor for his sucessor. In the palace, or in its shadow, literary, philosophical and math-ematical studies were pursued and meditation was practised; the term ‘court poet’ was not derogatory, but describes a deeply rooted tradi-tion of poetry in Arabia almost unchanged down to the present day. From a distance, modern-day court poets appear to be contemporary types, camouflaged with reasonably good English, a mobile phone and a limousine, and quite often their European colleagues can be led to assume –as they discuss Marx, Heidegger, Sartre and other great intellectuals – that theirs is an up-to-date, liberal stance. At close quarters, however, they can be seen to be the henchmen of the regime in power (complementing its torturers), whose task it is to eulogise the ruler, defame his enemies and justify the harsh measures taken against them. That was the way in the past, and remains so today. From the beginning, however, there was another tradition, that of rebel philosophers and poets who lived outside the palaces. Its traces have, to a great extent, been erased or falsified. These people are still oppressed, but thanks to global communications technology they can no longer be silenced. The Qur’an is the sacred text for over a billion people, and is sup-

34

He who lives with two faces will die faceless

35

posed to remain untouched; the Arabic of everyday life, scholarship and poetry, however, still needs radical reform. First, the building blocks of the language, its characters, must be reformed. The written language lacks certain letters such as E, O, P and W, which it needs in order to communicate easily with other languages and adopt their ex-pressions without having to write the words in the Roman alphabet. Farsi, spoken by Iranians, is able to absorb Arabic and Chinese ter-minology, as well as words in languages that use the Roman alphabet, without employing parentheses as a crutch. Arabic lines, pages and books are still harmonious to the eye, and reading flows smoothly from right to left, but such is not the case in Arabic books on sci-ence, psychology, philosophy and medicine, where the flow of words is often interrupted by Latinate expressions that must be read from left to right. European languages do not have this problem: for every sound in one European language, it is possible to find a combination of letters in another to reproduce it satisfactorily. In the Arab world, naturalising modern-day scientific, philosophi-cal, technical and sociological terminology in Arabic is a hesitant and uncoordinated process. But the express train of modernity merci-lessly thunders on; its rails are the new words produced by inventive minds. Yet one young Arab proudly informed me that he knew thirty synonyms for the word ‘lion’. An Arab linguist proudly announced that he had read of Ibn Faris’s 200 synonyms for ‘beard’. That was all very well for writers in the eighth century. But what about the Arabic words for ‘hydrogen’, ‘steering wheel’, ‘radio’, ‘ox-ide’, ‘computer’, ‘digital’? There was no answer. Depending on the former colonial power to which they were once subject – and this even in the first decade of the twenty-first century! – some Arabs adopt the English and others the French terms for all these words and more. It is estimated that modern physics has coined approxi-

36

mately 60,000 terms, chemistry, 100,000 and medicine, 200,000. Over 350,000 plant species are known to botany, and over 1 million animal species to zoology. Arabic must assimilate all these words if it is to be regarded as an international language. Yet it hesitates, nonplussed, before these innovations and the speed at which they come racing in. If it does not keep up, it will simply become antiquated.False prophets claim that the magical solution for preventing the lan-guage from becoming a fossil is for Arabs to abandon classical Arabic in favour of writing in local dialects; such ridiculous ideas are like an intellectual extension of nineteenth-century colonialism. What na-tion ever overcame a crisis by abandoning the language of its high culture in favour of dialect? A second tendency is to advocate the forsaking of Arabic script for the Roman alphabet, a change successfully imposed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on Turkish in 1928. This reform may appear sensible across the Arab world, and I fear it will materialise if the Arabs do not wake up, reform their language and script and put some effort into keeping pace with our changing global civilisation. At the same time, such a proposition would be unacceptable to most Arabs: Ara-bic characters are vital to their culture as a whole. A brave proposal for resolving the crisis of the Arabic language was made in the 1970s. To do it justice, the fundamental problem with Ar-abic script (which had been apparent from the first) must be empha-sised: its letters closely resemble each other. At an early date, scholars made several attempts at reform in order to eliminate ambiguity and misreading (particularly of sacred texts). The most radical step was taken in the eighth century under the Umayyads, when the aforemen-tioned fifteen letters acquired diacritical marks in order to draw a clear distinction between characters of the same basic shape. A great debt is owed in particular to the linguistic scholar al-Fara-

37

hidi (died 786) for this improvement. The Qur’an was recopied in this reformed script, and from then on any student could easily and correctly read the text, where once even scholars could find themselves baffled. This historical fact gives the lie to any Islamists who claim that language and writing are sacred. They are of human origin, and as such must be kept alive through innovation. Another problem, mentioned earlier, is that Arabic letters are writ-ten in four different ways depending on their placement at the begin-ning, in the middle or at the end of a word, or whether or not they stand on their own. These rules force students to learn over 100 letter forms, while a European child must learn only about fifty forms. The great Egyptian writer Taha Hussein (1882–1973) once sighed: ‘Others read in order to study, while we have to study in order to read.’ His complaint is more than justified. After years of hard work, the Iraqi poet, painter and calligrapher Muhammad Said al-Sakkar developed what he called a ‘concentrat-ed alphabet’ containing only fifteen letters, each with a single form wherever it appears within a word. Al-Sakkar referred to his inno-vation, which he patented, as ‘breaking the fetters of placement’. It was intended to facilitate reading and learning, and to simplify working on computers and in print. This new system was initially taken up enthusiastically in the Baghdad of Saddam Hussein. The dictator wished to present it as a brilliant achievement of the Ba‘th regime, but soon the explosive power of this reform became evident, and threatening to its rule. Al-Sakkar, although loyal to Saddam (he wrote some dreadful nationalist poems in support of the regime), was now accused of being a ‘follower of Freemasonry’ whose sole aim was to destroy Arab culture. Such condemnation, pronounced by Saddam’s uncle Khairallah Tulfah, was tantamount to a death

36

sentence; al-Sakkar fled the country in 1978, and has lived in exile in Paris since then. With all due respect to al-Sakkar’s efforts, it must be said that a reduction in the number of an alphabet’s characters impoverishes a language and impairs its elegance. The Qur’an would need to be recopied, and these changes taught to the Islamic world, or utmost chaos would ensue; two or three alphabets would co-exist in conflict with one another, causing only confusion. The sensible solution would be to extend the alphabet. The Qur’an could then remain intact, while the language of everyday life, poetry and science would be richer by four characters. Iranians, Pakistanis, Afghans and other Islamic peoples extended their alphabets long ago, and have fared no worse as Muslims than before.There is certainly no shortage in Arab countries of the financial means to support such a radical reform of the language and its script. A single day’s oil revenues would be enough to subsidise transla-tion of the most important books, and for the renovation of Arabic vocabulary. However, taking such steps would necessitate unity, de-mocracy and freedom in the Arab world – and such reform as that still lies in the remote future.

37

Rafik Schami

An extract from

The Calligrapher’s Secret

Translated from German by

Anthea Bell

Dedicated toIbn Muqla(886-940)

the greatest architect ofArabic charactrs, and his misfortune

38 39

The Old Town of Damascus still lay under the grey cloak of twilight before dawn when an incredible rumour began making its way to the tables of the little snack bars, and circulating among the first customers at the bakeries. It seemed that Nura, the beautiful wife of that highly regarded and prosperous calligrapher Hamid Farsi, had run away. April of the year 1957 brought summer heat to Damascus. At this early hour the streets were still full of night air, and the Old Town smelled of the jasmine flowering in the courtyards, of spices, of damp wood. Straight Street lay in darkness. Only bakeries and snack bars showed any light. Soon the call of the muezzins made its way down streets and into bedrooms. Muezzin started after muezzin, setting up a multiple echo.When the sun rose behind the eastern gate leading into Straight Street, and the last grey was swept from the blue sky, the butchers, vegetable sellers and the vendors at food stalls already knew about Nura’s flight. There was a smell of oil, charred wood and horse-dung around the place. As eight o’clock approached, the smell of washing powder, cumin, and here and there falafel began spreading through Straight Street. Barbers, confectioners and joiners had opened now, and had sprayed the pavement outside their shops with water. By this time news had leaked out that Nura was the daughter of the famous schol-ar Rami Arabi. When the pharmacists, watchmakers and antiques dealers were opening at their leisure, not expecting much business yet, the rumour had reached the east gate, and because by now it had as-sumed considerable dimensions it would not fit through the gateway. It rebounded from the stone arch and broke into a thousand and one

The Rumour

or

Hoe Stories begin

in Damascus

4140

pieces which scuttled away like rats, as if fearing the light, down the alleyways and into houses. Malicious tongues said that Nura had run away because her husband had been sending her letters speaking ardently of love, and the experienced Damascene rumour-mongers stopped at that point, well aware that they had lured their audience’s curiosity into the trap. “What?” asked their hearers indignantly. “A woman leaves her husband because he writes to tell her of the ardour of his love?”“Not his, not his,” the scandal-mongers replied with the calm assur-ance of victors, “he was commissioned to write to her by that skirt-chaser Nassri Abbani, who wanted to seduce the beauty with letters, but though he struts like a rooster the fool can’t write anything much himself, apart from his own name.” Nassri Abbani was a philanderer known all over the city. He had inherited more than ten houses and large orchards near the city from his father. Unlike his two brothers, Salah and Muhammad, who were devout, worked hard to increase their wealth, and were good husbands, Nassri slept around wherever he could. He had four wives in four houses, sired four children a year, and in addition he kept three of the city’s whores. When mid-day came, the scorching heat had driven all the smells out of Straight Street and the shadows of the few passers by were only a foot long, the inhabitants of the Christian, Jewish and Muslim quarters alike knew that Nura had run away. The calligra-pher’s fine house was near the Roman arch and the Orthodox church of St Mary, just where the different quarters came together.“Many men fall sick from arrack or hashish, others die of an insatia-ble appetite. Nassri is sick with the love of women. It’s like catching a cold or tuberculosis, either you get it or you don’t,” said the mid-

wife Huda, who helped all his children into the world and knew the secrets of his four wives. She placed the delicate cup containing her mocha on the table deliberately slowly, as if she herself suffered from this severe diagnosis. Her five women neighbours nodded, holding their breath. “And is the disease infectious?” asked a plump woman with pretended gravity. The midwife shook her head, and the others laughed, but with restraint, as if they thought the question embar-rassing. Driven by his addiction, Nassri paid court to all women. He did not distinguish between society ladies and peasant girls, old whores and adolescents. It was claimed that his youngest wife, six-teen-year-old Almas, had once said:, “Nassri can’t see a hole without sticking his thing into it. I wouldn’t be surprised if he came home one day carrying a swarm of bees on his prick.”

And as usual with such men, Nassri’s heart really burned only when a woman turned him down. Nura did not want to know anything about him, and so he was almost crazy for love of her. People said he hadn’t touched a whore for months. “He was obsessed with her,” his young wife Almas confided to the midwife Huda. “He hardly ever slept with me, and if he did lie beside me I knew his mind was on the other woman. But I didn’t know who she was until she ran away.”Then the calligrapher had written love letters that could have melted a heart of stone for him, but to the proud Nura that was the height of impertinence. She gave the letters to her father. The Sufi scholar, a man of exemplary calm, wouldn’t believe it at first. He suspected that some wicked person was trying to destroy the calligrapher’s marriage. However the evidence was overwhelming. “It wasn’t just the callig-rapher’s unmistakable writing,” said the midwife, and added that

4342

Nura’s beauty was praised in the letters so precisely that apart from herself and her mother, only her husband and no one else could have known all the details. And now the midwife’s voice sank so low that the other women were hardly breathing. “Only they could say what Nura’s breasts and belly and legs looked like, and where she had a lit-tle birthmark,” she added, as if she had read the letters herself. “And all the calligrapher could say,” added another of the neighbours, “was that he hadn’t known who that goat Nassri wanted the letters for, and when poets sing the praises of a strange beauty with whom they aren’t personally acquainted, they describe only what they know.”“What spinelessness!” This sigh went from mouth to mouth over the next few days, as if all Damascus could talk of nothing else. Many would add, if there were no children within hearing distance, “He’ll just have to live with the shame of it while his wife lies underneath that bed-hopping Nassri.” “She isn’t lying underneath him. She ran away and left them both. That’s the strange part of it,” malicious tongues would say mysteriously, putting the record straight.Rumours with a known beginning and end do not live long in Da-mascus, but the tale of the beautiful Nura’s flight had a strange be-ginning and no end. It circulated among the men from café to café, and from group to group of women in their inner courtyards, and whenever it passed from one tongue to the next, it changed. Tales were told of the dissipated excesses into which Nassri Abbani had tempted the calligrapher in order to get access to his wife. Of the sums of money that he had paid the calligrapher for the letters. Nassri was said to have given him their weight in gold. “That’s why the grasping calligrapher wrote the love letters in large charac-ters and with a wide margin. He could make a single page into five,” said the scandal-mongers.

All that may have helped to make the young woman’s decision easier for her. But one kernel of the truth remained hidden from everyone. The name of that kernel was love. A year before, in April 1956, a tempestuous love story had begun. Nura had reached the end of a blind alley at the time, and then love suddenly broke through the walls towering up before her and showed her a crossroads of opportunity. And Nura had to act.But as the truth is not as simple as a apricot, it has a second kernel, and not even Nura knew anything about that one. The second kernel of this story was the calligrapher’s secret.

4544

“Like the mythopoeic India of Salman Rushdie’s the main protagonist of Schami’s encyclopedic, jigsaw puzzle of a novel is a country: Syria… Schami gives voice to the entire chorus of Damas-cus life… Schami, a major international talent, has a broad range, from the scatological to the sexually comic to the painful, and with this extraordinary book deserves to establish an American audience.” (starred review and a PW Pick of the Week)

“...may turn out to be the first Great Syrian Novel. illumines almost every side of love, as well as fear, longing, cruelty and lust. Darkness and light alternate like the basalt and marble stripes on Damascene walls, and the novel's structure is just as strong...as expansive, as comprehensive, as

“Romeo and Juliet meets Arturo Pérez-Reverte and John le Carré in the dusty streets of Damascus… A rewarding and beautifully written, if blood-soaked, tale.”

—Publishers Weekly

The Dark Side of Love

Midnight’s Children,

War and Peace.”—The Guardian

—Kirkus Reviews

PRAISE FOR RAFIK SCHAMI’S

The Calligrapher’s Secret

PRAISE FOR RAFIK SCHAMI’S

The Dark Side of Love

4746

SALES & ORDERING INFORMATION

“Warmly observed, richly detailed… Schami's fine portrait of life in Damascus, Syria, in the middle of the 20th century is filled with a compelling set of characters… exquisite storytelling… A novel to be savored.”

“A literary masterpiece… a sensual homage to Damascus… you only wish it were a never-ending story.” —Sabine Tesche,

—Publishers Weekly

Hamburger Abendblatt

(starred review)

PRAISE FOR RAFIK SCHAMI’S

Damascus Nights

Order from your local bookseller, visit our website at www.interlinkbooks.com,

or call us Toll Free at 1-800-238-LINK.

INTERLINK PUBLISHING46 CROSBY STREET, NORTHAMPTON, MA 01060

The New York Times Book Review“Timely and timeless at once.”—Malcolm Bradbury,

“A picturesque collection of tales… wonderfully contemporary.”—Richard Eder,

“A master spinner of innocently beguiling yarns, slyly oblivious to the Western cartographies of narrative art and faithful only to the oral itineraries of the classical Arab storytellers, Rafik Schami plays with the genre of the Western novel, and he explodes it from within.”—Anton Shammas

“This wonderful book is enlightening and endearing, witty and wise… Highly recommended…”

Los Angeles Times Book Review

—Library Journal