ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu · Web viewThe interesting aspect about Webster’s argument, as historian...

Transcript of ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu · Web viewThe interesting aspect about Webster’s argument, as historian...

Tackling the Monster Bank:Andrew Jackson, Nicholas Biddle,

and the Bank War

Anthony Ciardiello

Senior Thesis

April 20, 2010

Acknowledgements

I would like to sincerely thank Professor Sean Adams, who has served as my advisor over the

course of this past year. His advice, guidance, and wisdom have been truly invaluable as I em-

barked on this academic pursuit. Additionally, his courses on the Early Republic, as well as the

History of American Capitalism, were taught with aplomb and served to catalyze my interest in

the Bank War and the Jacksonian Era. Without his tutelage, this thesis would not have been pos-

sible.

I would also like to extend my gratitude towards a former colleague of mine, Matthew Winters.

Mr. Winters was the first person to introduce me to Andrew Jackson and all of his eccentricities.

Our initial discussions regarding America’s seventh president first piqued my interest in Andrew

Jackson, and led me to pursue the topic further.

Finally, it is imperative that I acknowledge the supportive role my parents, David and Susan,

played in the process of writing this thesis. My father, as a small business owner, instilled the

ideas of capitalism, democracy, and the American spirit ever since my youth, which subse-

quently led me to pursue topics in political economy. Additionally, my mother inculcated a love

of reading and books, a passion which continues to this day. Their love and support has been a

constant source of inspiration for me, and this thesis is dedicated to them.

Table of Contents

Section Name Page Number

Introduction 1

Beginnings

Andrew Jackson 3

Nicholas Biddle 7

Central Banking

First Bank of the United States 11

Henry Clay and the American System 13

Second Bank of the United States 14

The Bank War Begins

Clay’s Machinations 18

Arguments Against, and the Veto 21

Clay, Webster, and Arguments For 28

The Election of 1832 33

The War Rages On

Removing the Deposits 35

End Game 40

Examining the Bank War Historiographically

Arthur Schlesinger 42

Murray Rothbard 44

Bray Hammond 46

Susan Hoffman 48

Conclusions 50

Epilogue: The Monster Bank Today 53

Bibliography 57

Introduction

Throughout the history of mankind, politics and the economy are two factors that always

play a role in the shaping of a nation; one invariably affects the other. So it was the case in the

nascent United States of America, a nation conceived in liberty, yet still struggling with its iden-

tity in the early nineteenth century.

During the 1830s, the United States faced many new movements, both religious and po-

litical, and was struggling with the incompatibility of slavery with the ideals set forth in the Dec-

laration of Independence. Yet attention at the highest levels of government was not focused on

these events in particular, but another situation entirely. The Second Bank of the United States

had been an integral part of the nation’s economy for over fifteen years, yet with the election of

the nation’s first populist president, the role and privileges of the Bank were put into question.

In this thesis, the role and function of the Second Bank of the United States will be ex-

plored, as well as the characters that both supported and opposed its role during the Early Repub-

lic. The two primary actors (in what would become known to history as the Bank War) are the

seventh president of the United States, Andrew Jackson, and his counterpart, the President of the

Second Bank of the United States, Nicholas Biddle, although the actions of others, such as the

statesman Henry Clay, will not be neglected. After analyzing opinions of the time from newspa-

pers and other publications, the Bank War will be examined historiographically. One hundred

and seventy years after the end of the events of the 1830s, there are still differing schools of

thought regarding the Bank War. Certain historians fault the actions of Andrew Jackson, who, in

an attempt to act as a president of the people, instead crushed an institution benefitting them.

Others place the blame not on the President, but the Bank itself. If Biddle had not been as arro-

1

gant and vengeful, he very well could have spared the American people from an economic con-

traction and recession.

This thesis does not set out to examine the entire Jacksonian Era; indeed, entire volumes

of work have been dedicated that topic. During what can be called the Age of Jackson, the

United States had to address many growing pains, such as tariffs, Indian removal, internal im-

provements, nullification, and emerging social movements. Instead, the focus of this paper will

be on the Bank War and the nascent U.S. economy. When appropriate, these other movements

may be mentioned in order to highlight or augment the point at hand.

Although the Bank War occurred almost two centuries ago, important lessons can still be

gleaned from it. The Bank War greatly increased the power and role of the presidency; it estab-

lished the President of the United States as the dominant figure in American politics. It concurred

with the rise of democracy in America; for the first time, the electorate, not the eastern bankers

or the political class, had a say in the direction of the American economy. As such, Jackson used

his power as the president to implement policies conducive to the will of the people. As was the

case then, the United States today still struggles with and argues about the proper role of the cur-

rent central bank, the Federal Reserve, in contemporary society. With the current economic melt-

down still fresh in the minds of the public, the argument over what is to be done now versus what

has been done previously takes on a new historical significance. The characters of Andrew Jack-

son and Nicholas Biddle live on.

2

Beginnings

Andrew Jackson

Born in the Waxhaws, a frontier region between North Carolina and South Carolina, An-

drew Jackson was the third child (and third son) of Andrew Jackson, Sr. and Elizabeth Hutchin-

son Jackson. However, Jackson’s mother was widowed when her husband injured himself chop-

ping wood for the family. Andrew Jackson was born a few weeks later, and named after his de-

ceased father.

The environment in which the president was raised would shape much of his future per-

sona. Personal violence was quite common on the Carolina frontier, and “young Andrew Jackson

grew up certain that a well-known willingness to repay violence with more violence was essen-

tial to a respected man’s reputation.”1 Young Andrew Jackson was wild and reckless, engaging

in fights with children two or three times his own size.2 One anecdote that has survived history

has Jackson firing an overly-loaded musket to prove his strength. He was thrown to the ground

by the blast, and as he got up off the floor, he yelled to the boys around him, “By God, if one of

you laughs, I’ll kill him!”3 No one had the gall to challenge him; Jackson’s threats were often

quite credible.

The British invaded the Carolina highlands in 1780, and Jackson enlisted in the Revolu-

tionary Army as a courier, joining his elder brothers who were serving as soldiers. His eldest

brother died in battle, and both he and his younger brother were captured. It is during his captiv-

ity where one of the stories regarding Jackson’s resilience and toughness emerges. When ordered

1 Henry L. Watson, Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay: Democracy and Development in Antebellum America (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1998), 23.2 Robert Remini, Andrew Jackson (New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1966), 16.3 Ibid.

3

by a British officer to clean his boots, Jackson responded, “Sir, I am a prisoner of war, and I

claim to be treated as such.”4 Angered by the young American’s impetuousness, the British offi-

cer raised his saber and slashed Jackson across his face and outstretched hand, giving him scars

that he would carry with him for the rest of his life.

When Andrew and his surviving brother contracted smallpox, his mother was able to se-

cure their release from captivity. With her boys’ safety ensured, Mrs. Jackson traveled to

Charleston to nurse some of her other relatives back to health. It was on this ship she contracted

cholera and died. Andrew’s brother, Robert, took a turn for the worse, and he, too, perished.

Now, Andrew Jackson was an orphan in the world at the age of fourteen, the British taking away

his entire family from him in one way or another. It was from this point on he developed a deep

antipathy towards anything and everything British.

It speaks to Jackson’s tenacity that rather than giving up at this point in his life, he forged

ahead. Moving to Salisbury, North Carolina in 1783, he entered the law office of Spruce McCay

to learn what he decided would be his future profession.5 Three years later, he was admitted to

the bar. Although he did not have any formal legal education, he was not, as many future genera-

tions would paint him, unintelligent by any means. He subsequently moved out to the western

frontier, in to the area that would become Tennessee, and practiced small claims law and cases

involving assault and battery. He rose quickly, becoming a delegate to the Tennessee constitu-

tional convention in 1796. When Tennessee became a state later that year, he was elected as the

state’s at-large Representative. The following year, he became one of the state’s Senators, but re-

signed that post to sit on the bench of the Tennessee Supreme Court, where he served until 1804.

4 Ibid., 18.5 Ibid., 21.

4

By his thirtieth birthday, Jackson had served in both branches of Congress and on the

Supreme Court of the state of Tennessee, but his greatest claim to fame was yet to come. In

1801, Jackson had been appointed to the rank of Colonel in the Tennessee militia. During the

War of 1812, Jackson was first charged with attacking the “Red Stick” Creeks. He attacked and

defeated about eight hundred Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. As a reward for his brav-

ery, he was appointed to the position of Major General, and placed in charge of the seventh mili-

tary district, which covered Tennessee, Louisiana, and the Mississippi Territory.6

Upon hearing that the British were preparing to mount an attack on New Orleans, Jack-

son headed there to take control of the city’s defenses. He assembled a hodgepodge of men will-

ing to fight, including pirates, Frenchmen, Creoles, and free Negroes alongside his militia regu-

lars. On January 8, 1815, Jackson’s forces easily held off a numerically superior British force,

suffering 71 casualties to Britain’s 2,037. As Robert Remini notes, “It was an unbelievable vic-

tory. Never had American arms sustained so overwhelming, so complete a victory as this. Never

by force of arms had Americans proved so convincingly their right to independence.”7 This vic-

tory greatly enhanced Jackson’s character and made him a legend in the United States. Alexis de

Tocqueville, writing Democracy in America two decades later, remarked, that Jackson “was

raised to the Presidency, and has been maintained there, solely by the recollection of a victory

which he gained, twenty years ago, under the walls of New Orleans.”8

Over the course of the next decade, Jackson continued his military career, serving in the

First Seminole War and subsequently acting as the military governor of Florida. His home state

of Tennessee appointed him to the Senate once again, and he was a candidate for the presidency

in the election of 1824. By this time, the Republican Party was the only national party, and it

6 Ibid., 61.7 Ibid., 72.8 Alexis de Tocqueville. Democracy in America (New York: The Century Company, 1898), 369.

5

fielded four candidates: General Jackson; John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State; William

Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury; and Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House. After the

election results came in, Jackson had received a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote,

but not an outright majority as required by the United States Constitution. As per the Twelfth

Amendment, the election was thrown to the House of Representatives, where only the top candi-

dates were to be voted on. This excluded Henry Clay, the Speaker. As Adams’s political views

were closer to Clay’s, the Speaker threw his support to the Secretary of State; Adams won on the

first vote. Jackson was furious; he had received a plurality of the votes, so clearly the will of the

American people was his. He was further enraged when Henry Clay was appointed by Adams to

be his Secretary of State. Jackson and his supporters accused Adams and Clay of striking a “cor-

rupt bargain.” The entrenched elites had acted out of their own interests, not those of the people

of the United States, continuing the common Jacksonian theme.

After the election of 1824 had been decided, Jackson and his supporters almost immedi-

ately went on the offensive, preparing for the next presidential election to be held four years

later. Their message was simple enough: “Jackson and Reform.” They attacked the Adams-Clay

coalition for acting without the backing of the American people. The Adams Administration, ac-

cording to the Jacksonians, from the beginning had engaged in a “giant act of fraud – one that, to

succeed, required shifting as much power as possible to Washington, where the corrupt few

might more easily oppress the virtuous many…”9 The veracity of such claims is debatable, but

nonetheless, they were effective, as Jackson easily won the presidency, carrying fifteen of

twenty-four states and fifty-six percent of the popular vote. The Man of the People had made it to

the White House.

9 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005), 178.

6

Even though Jackson had served

as a Congressman, Senator, Judge, and

now President, he never truly felt as if

he were a part of the system. Rather, he

prided himself on being apart from the

system. Furthermore, his small govern-

ment philosophy came from his own

personal experiences. Orphaned at a

young age, he was able to succeed in

the world without the aid or assistance

of government. He was a self-made man, and firmly believed that all Americans should be able

to succeed as he had. That philosophy directly conflicted with the one held by the President of

the Second Bank of the United States, Nicholas Biddle.

Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle, born January 8, 1786, was nineteen years Jackson’s junior. A member

of the prominent Biddle family, the young Nicholas was incredibly gifted, enrolling at the Uni-

versity of Pennsylvania at the age of ten. When the University refused to confer a degree due to

his young age, Biddle transferred to Princeton. Like most of his classmates, Biddle was a Feder-

alist, and in his writings, he accused Jefferson’s Republicans of “seeking to impose an absolute

and tyrannical government upon the country.”10 Another one of his compositions illustrated his

skepticism of republics, insofar as they “were in constant danger from demagogues…The fires of

10 Thomas Payne Govan, Nicholas Biddle: Nationalist and Public Banker (1786 – 1844), (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1959), 7.

7

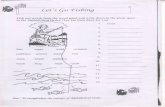

This painting depicts Andrew Jackson’s inauguration on March 4, 1829. Due to campaigning as the “people’s president,” a large crowd descended onto the Executive Mansion, and would only be dispersed when large bowls of punch and liquor were placed on the lawn.

Picture courtesy The Library of Congress

discord rage with dreadful fury and unless extinguished by the wisdom of citizens may involve

our country in one great conflagration.”11

After graduating as valedictorian of his class at Princeton at the age of fifteen, Biddle be-

gan to study law. He quickly grew tired of the profession, and yearned to travel. Thanks to the

influence of his father, Biddle was hired as a secretary for the United States Minister to France,

John Armstrong. During this time, he also served as secretary for James Monroe, who was the

Minister to Great Britain. Monroe took a liking to the young Biddle, and the professional rela-

tionship that developed between the two men would be crucial later in Biddle’s life.

Returning to the United States at the end of the decade, Biddle practiced law and wrote

for various newspapers. His bid for Congress failed, so he took an increasing interest in com-

merce and finance. The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, and the follow-

ing year, James Monroe, now the President of the United States, appointed Biddle as one of the

federal government directors. In his letter of acceptance, he told the President: “The truth is, that

with all its faults, the Bank is of vital importance to the finances of the government and an object

of great interest to the community.”12 This appointment would define Biddle’s career for the next

twenty years, and even Biddle himself could not have possibly imagined where it would take

him.

While under the tutelage of then-Bank President Langdon Cheves, he learned the positive

value the Bank could have if managed correctly. The previous Bank President, William Jones,

was a terrible administrator and had almost brought the Bank to ruin (as will be explained in fur-

ther below), and Cheves brought it back from the brink by strongly contracting the money sup-

11 Ibid., 8.12 Ibid., 59.

8

ply. This proved to be a highly unpopular move, for although the Second Bank survived, it threw

the national economy into a tailspin, and played a role in causing the Panic of 1819.

Biddle’s own philosophy was strongly influenced by the time he spent at the bank. His

study of political economy had led him to reject the classical liberalism as preached by Thomas

Malthus, David Ricardo, and James Mill (the father of the even more famous John Stuart Mill).

According to historian Thomas Govan, Biddle “had seen too clearly during the course of the War

of 1812 and its aftermath how business activity responded to the expansion and contraction of

the money supply to believe that economic activity was governed by natural laws with which

men interfered at their peril.”13 Thus, Biddle was not an advocate of the type of laissez-fair eco-

nomics first preached by Adam Smith a half century hence; he firmly believed that enlightened

civil servants, such as himself, with the nation’s best interest in mind, were in the best position to

manage and direct the American economy.

When Langdon Cheves retired as Bank President in the summer of 1822, Biddle was

elected to the position. Biddle set out immediately to grow and strengthen the Bank, but to do so

amicably, without antagonizing the state banks. He was somewhat successful in this regard;

working together, the National Bank and state banks were able to collaborate in providing credit

for an expanding economy. With the economy now growing, the Bank was able to expand the

money supply to further this growth, and by 1828, “a surplus of $1,500,000 had been accumu-

lated, and in the later half of that year the Bank began paying dividends at the rate of 7 percent

per annum.”14

Biddle was quite pleased with himself; he had accomplished what he had set out to do.

When Andrew Jackson was elected to the presidency in 1828, Biddle did not display the level of

13 Ibid., 70.14 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States (Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1949), 4.

9

animosity towards the incoming president as many of his colleagues did. A learned man himself,

he believed that once Jackson knew the importance of the Bank, he would not actively interfere

with it. Besides, the Bank’s charter was not set to expire for another eight years, and the Bank

was not a contentious issue in the 1828 election; Biddle saw no need to worry.

Biddle himself was loath to get involved in politics; he preferred that the Bank stay above

the political fray. It was of his opinion that the Bank was superior to the normal political pro-

cesses of a democracy and that his Bank should not be responsive to the will of the people. He

decried the “‘violence of the party,’ and said he felt ‘no disposition to become the follower of

any sect, or to mingle political animosities with the intercourse of society.’”15 His disdain of pop-

ular democracy combined with a fervent belief in his Bank led him to certain arrogance regard-

ing the position of the Bank in the American Republic. In an interview with Alexis de Toc-

queville, who was in Philadelphia doing research for what would become Democracy in Amer-

ica, Biddle showed his contempt for political parties by remarking,

The party standard has really been knocked down for good and all....Since then there have been people who support the administration and people who attack it; people who extol a measure and people who abuse it. But there are no parties properly so called, op-posed one to the other and adopting a contrary political faith. The fact is that there are not two practicable ways of governing this people now, and political emotions have scope only over the details of this administration and not over its principles.16

Thus, in Biddle’s mind, there was no further need for debate. He and his patrons at the Bank

would decide what policy to implement, what policies would be best for the country. The more

years he spent at the Bank, the more arrogant he became, and this pride would be detrimental in

the fight to come.

15 H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, (New York: Anchor Books), 458.16 Ibid., 457.

10

Central Banking

First Bank of the United States

Central Banking had always been a contentious issue in the early years of the United

States, and the conception of one, monolithic bank operating at the behest of business interests

over the will of the people was a view held by many Americans. A central bank controlling the

nation’s finances by manipulating credit and the flow of reserves directly conflicted with the

constitutional view held by many of a limited government. However, there were others who

viewed the idea of a central bank essential to the future growth and prosperity of the United

States of America.

The nation’s first attempt at central banking came in the form of the First Bank of the

United States (First B.U.S.). Proposed by Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, the

Bank was officially chartered on February 25, 1791. The Charter, lasting twenty years, estab-

lished a mint and an excise tax. Additionally, according the Hamilton, the Bank would serve to

establish credit for the new nation, resolve the fiat currency issue (that is, the “Continentals” is-

sued by the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War), and also ensure financial or-

der. The bank was to be private, and could not buy government bonds. Interestingly, although a

private institution, the Bank acted as the official bank of deposit for the United States govern-

ment, and as such, the Secretary of the Treasury would be free to remove deposits and inspect

the Bank’s books.17

Unfortunately for Hamilton, while he intended for the Bank to be national in character, in

actuality it benefitted Northern commercial interests much more than Southern planters and

17 That is, all revenues (i.e. taxes and tariffs) collected by the government of the United States of America were put into the Bank.

11

landowners. Chief among those who spoke out in opposition were Thomas Jefferson and James

Madison. Jefferson, a strict constructionist, claimed that the establishment of the Bank violated

the Constitution, stating, “I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground:

That ‘all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to

the States, are reserved to the States or to the people.’…The incorporation of a bank, and the

powers assumed by this bill, have not, in my opinion, been delegated to the United States, by the

Constitution.”18

Whereas the Federalists allied themselves with bankers and merchants along the East

Coast, Jefferson believed in the American planter and farmer. Jefferson preached a small govern-

ment ideology, where the states would be co-equal partners with the Federal Government, and,

as stated above, a strict interpretation of the Constitution. If the Constitution did explicitly grant

the Federal Government a certain power, than that power was reserved to the states. After Jeffer-

son was elected to the presidency, he did not actively attack the bank, but was content to allow

its charter to expire when the time came. That is exactly what occurred in 1811, when James

Madison held the office. Similar in ideology to his predecessor, Madison, a Virginian, believed

that the South did not benefit from a bank, and that it was unnecessary. However, circumstances

in the near future would force Madison to change course and establish the Second Bank of the

United States, an institution even larger than its predecessor.

This begs the question: why should the same political party, and even many of the same

individuals, who had opposed the Bank’s rechartering and demonized the institution, suddenly

have an about-face a mere five years later? According to historian George Rogers Taylor, the

chief reason was the War of 1812: “By the beginning of 1815 the credit of the United States had

18 Thomas Jefferson, “Opinion against the Constitutionality of a National Bank” from Volume III of The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Wikisource, http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Opinion_against_the_Constitutionality_of_a_Na-tional_Bank (accessed April 9, 2010).

12

fallen to its lowest ebb since the founding of the federal government….Banks had multiplied

during the war and greatly extended their note issues. By the fall of 1814 most banks outside

New England had been forced to suspend specie payments, and…prices had risen to the highest

point for the whole nineteenth century.”19 Congress had not passed appropriation taxes in time

for the war either, compounding the problem.

Henry Clay and the American System

Thankfully for the United States, the war ended in 1815, and a more severe crisis had

been averted. But faced with the specter of mounting debts and crippling inflation, Madison’s

Republicans set about establishing a second national bank. Chief among the advocates for the

Second Bank of the United States was a Congressman from the State of Kentucky, Henry Clay.

Also serving as the Speaker of the House, Clay brought the Western perspective into a debate

that had, prior to then, been exclusively North-South. Clay’s background was similar to Jack-

son’s, but there were some marked similarities. Although both had training in law and had come

of age in the American West, Clay’s education went much further, studying at William and Mary

under the prominent judge and law scholar George Wythe (whose pupils at one time included

Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Marshall).

By 1811, Clay was elected to the House of Representatives as well as to the Speakership.

As Speaker, he led the “War Hawk” faction of the House, who advocated war with Great Britain

due to her violation of American shipping rights. After the War of 1812 had ended, he, along

with fellow Congressman John C. Calhoun, passed the Tariff of 1816, which served as part of

Clay’s new “American System.” According to historian Merrill Peterson, “Viewed as a theory of

political economy, the American System disputed the fundamental ‘free market’ premises of the

19 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 1.

13

classical school. It believed that a youthful economy, like the American, required the fostering

hand of government; it believed a republican government responsive to the interests of the peo-

ple ought to promote employment, productivity, and wealth…”20

This concept of government directly conflicted with the Jacksonian ideal of limited gov-

ernment and self-subsistence of the individual. Although both Clay and Jackson were members

of the same political party, the Republican Party, their vision of the future of the country could

not have been more markedly different.

The American System advanced by Clay advocated the subsidizing of roads to connect

the West to the East. The western states would ship raw goods to the east via these roads, which

would then be turned into goods to be sold by eastern manufacturers. Construction of these roads

would be funded by the sale of federal lands out West and by the Tariff mentioned above. This

Tariff would also serve as a protectionist measure to advance American interests and goods over

those produced overseas. Finally, the capstone of the American System was the Bank, which

would stabilize currency and keep the risky state banks in check.

The Second Bank of the United States

Thus, Clay firmly sided with the Madison Administration when the chartering of a Sec-

ond Bank was presented to Congress. After the War of 1812, the state banks, which had stepped

into the role of lender to the Federal Government, issued paper money as currency. The problem

with this situation lay in the fact that different state banks had different exchange rates with other

state banks. For example, New York banks might accept notes from Boston banks, but Boston

banks might not accept notes from banks in New York. Pennsylvania banks would offer a dis-

20 Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 69.

14

count on New York notes, but New York would not accept notes from Philadelphia. In other

words, there was no uniform standard of currency throughout the rapidly growing nation. “With

the state banks still refusing to pay specie on their notes, each bank’s notes were depreciated at

different rates in different places, and the Treasury was hard to move its funds from places of

collection to places of payment.”21

Additionally, liquidity had dried up, as state banks refused to pay specie (that is, gold

and silver) for certain notes. George Taylor explains, “Although earlier proponents had looked

upon it mainly as a means for aiding the treasury in financing the war, the chief objects sought

by the Bank’s sponsors in 1816 were to force the state banks to resume specie payments and to

establish a satisfactory national currency.”22

Thus, the Second Bank of the United States was chartered out of a perceived necessity,

rather than some type of ideological goal. With its headquarters in Philadelphia, near the old

headquarters of the First Bank, the Second Bank could establish branch banks anywhere in the

nation. It was a public-private joint venture, as the Federal Government appointed five of its

twenty-five directors, ascribed for a fifth of the stock in the bank, and acted as the government’s

official bank of deposit.23 William Jones, the former Secretary of the Navy and Acting Secretary

of the Treasury was selected as the Bank’s first president.

What followed next would have strong implications for the future of the Bank. While a

shrewd politician, Jones made for a terrible Bank president. During his tenure, the branch banks

established were subjected to little or no control by the parent institution. In one particularly

egregious example, the operators of the Baltimore Branch “easily robbed it of more than a mil-

21 Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 71.22 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 2.23 Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution, 72.

15

lion dollars before they were exposed and the branch forced into the hands of a receiver.”24

Malfeasance and incompetence were rampant from the smallest of branch banks all the way up

to the primary bank in Philadelphia. Under these conditions, in January 1819, Jones was allowed

to resign.

These events subsequently led to the Panic of 1819. Because the Bank had been so lax

with credit and the distribution of fiat currency, a huge economic bubble had been created. State

banks were allowed to pursue inflationary policies, without any type of reprimand or correction

from the central bank. By late 1818, the Bank knew it was in trouble, and started contracting the

money supply: total notes and deposits fell from $21.9 million in June 1818 to $11.5 million one

year later, a contraction in the money supply of almost fifty percent. As a result, prices fell pre-

cipitously. From this, businesses could no longer pay their debts or their employees, and many

went bankrupt. An estimated $100 million dollars in mercantile debt to Europe was liquidated,

and some areas out West reverted to using a barter system for transactions.25 Hard money econo-

mist and historian William Gould summed up the Panic as such: “the Bank was saved, and the

people were ruined.”26

The spectacular failure of Jones, combined with the Panic of 1819, proved in Jackson's

mind that banks were nothing but corrupt institutions incapable of managing an economy. The

Bank had done nothing to stem the Panic, and might have in fact contributed to it. From this

point on, Jackson stood firmly against the Second Bank of the United States. A war hero and

self-made man of the West, he positioned himself as a man of the people against the entrenched

interests of the Eastern elite.

24 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 2-3.25 Facts and figures courtesy Murray Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II (Auburn, AL: Ludwig Vin Mises Institute, 2002), 89-90.26 William M. Gouge, A Short History of Paper Money and Banking in the United States (Philadelphia: T.W. Ustick, 1833), 110.

16

Faced with the first real economic depression the country’s short history, many Ameri-

cans turned against the Bank. The perceived failure of the financial institutions to prevent and

address the Panic of 1819 laid the foundation for what would become known as Jacksonian

Democracy. As would be the case in the future (and as is the case currently after this most recent

fiscal crisis), anti-establishment (and by extension, anti-Bank) sentiments were very high.

The Panic of 1819 also converted to Jackson's thinking many of those who would be-

come part of Jackson's inner circle, including Thomas Hart Benton, James K. Polk, and Jackso-

nian economists Amos Kendall and Condy Raguet. All of these men were “converted to hard

money and 100-percent reserve banking…[and] pinned the blame for boom-bust cycles on infla-

tionary expansions followed by contractions of bank credit.”27

Unfortunately for the Jacksonians, their ideology hit a constitutional snag that same year.

State banks were growing more and more tired of the National Bank establishing branch banks in

what they considered their operational territory. Two states, Indiana and Illinois, prohibited in

their constitutions the establishment of any bank other than state banks. Additionally, Maryland,

Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Ohio “levied taxes upon the branches of the

Bank of the United States which would have driven the Bank from the states imposing them.”28

However, James McCulloch, head of the Baltimore Branch of the Second Bank of the United

States, refused to pay the tax. The case was eventually appealed to the Supreme Court.

In McCulloch v. Maryland, the state of Maryland essentially argued that since chartering

a bank was not one of Congress’s enumerated powers, the Bank of the United States was uncon-

stitutional. Furthermore, Maryland had the Tenth Amendment on their side as well, as it states

that any powers not delegated to the Federal Government by the Constitution are reserved to the

27 Murray Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking, 91.28 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus, 3.

17

states, and to the people. Chief Justice John Marshall disagreed with Maryland’s assertions; the

Court instead found unanimously in McCulloch’s favor.

Marshall justified his decision by invoking the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Con-

stitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18). While the Constitution does not explicitly give Con-

gress the right to charter a bank, it can do so in order to fulfill its enumerated powers, in this in-

stance the right to collect and expand revenue. Using Hamiltonian language, the Court con-

cluded: “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means

which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but con-

sist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.”29 Famously declaring that

“the power to tax involves the power to destroy,” Marshall wrote that were a state were permit-

ted to tax the Federal Government, they may “tax all the means employed by the government, to

an excess which would defeat all the ends of government. This was not intended by the Ameri-

can people. They did not design to make their government dependent on the states.”30 Thus, in all

instances, Federal law would trump state law. The Bank, being a Federal institution, was thus

constitutional.

The Bank War Begins

Clay’s Machinations

Although Jackson was not fond of the Bank, he did not intend to make it a major point of

contention during his presidency. In Jackson’s First Annual Message to Congress (what today

would be called the State of the Union) on December 8, 1829, the president barely mentioned the

29 McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819), accessed online at http://laws.findlaw.com/us/17/316.html.30 Ibid.

18

Bank at all, only saying near the end of the speech that, “Both the constitutionality and the expe-

diency of the law creating this bank are well questioned by a large portion of our fellow citizens,

and it must be admitted by all that it has failed in the great end of establishing an uniform and

sound currency.”31 Indeed, the previous election had not focused on the issue of the Second Bank

of the United States, but instead the tariff, partially because mentioning a contentious issue like

the Bank may have upset Jackson’s delicately balanced coalition.32

Jackson and Biddle finally had the opportunity to meet during Jackson’s first year in of-

fice; this would be the first and last time the two men would talk to each other face-to-face. Bid-

dle had sent Jackson a plan to pay off the federal debt, for which Jackson thanked him. During

this meeting, the two men also discussed banking, and Jackson shared his opinion of the Bank

with its president, telling Biddle that he still believed that Congress did not have the power to

charter a bank outside the borders of Washington D.C. He then added, “I do not dislike your

bank any more than all banks. But ever since I read the history of the South Sea bubble I have

been afraid of banks.”33

After this meeting, Biddle felt fairly certain that while Jackson had a personal animus

against banks, this would not necessarily translate into public policy. Biddle sincerely believed

that Jackson would, in his mind, put aside his personal prejudges against the Bank and do what

was in the best interest of the nation. Jackson’s conception of what was best for the nation,

though, was much different than Biddle’s. He would certainly not support a rechartering of the

bank; however, this did not mean he would be actively hostile towards it. Indeed, had not the

Bank issue come up, he very well may have let the Second Bank run the same course as the First,

31 Andrew Jackson, "First Annual Message to Congress," The American Presidency Project, http://www.presiden-cy.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29471.32 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy, 252.33 H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, 460.

19

allowing its charter to simply expire without making much of a fuss. According to H.W. Brands,

“Jackson hadn’t intended to fight the 1832 election on the Bank issue. In his annual message of

December 1831 he had barely mentioned the subject.”34 Thus, for the first three years of his pres-

idency, the Bank was a non-issue.

Henry Clay, now a Senator, had different ideas. He knew that Jackson remained a popu-

lar president with the American people, and that, barring any major improprieties, he would eas-

ily win re-election. Clay thus needed a wedge issue, an issue which to embarrass Jackson and

dampen his popularity, an issue he, as a presidential candidate, could win on. Clay thus ap-

proached Biddle, suggesting that they push the Bank’s recharter date four years early. In a letter

to Biddle, Clay wrote, “If, as I suppose, [Jackson] would reject it, the question would be immedi-

ately, in consequence, referred to the people, and would inevitably mix itself with our elec-

tions.”35 Yet this is exactly what Biddle did not want: for his Bank to become part of a partisan,

political battle. As previously mentioned, he believed that his precious institution should be

above common politics, and was not initially well-disposed towards Clay’s entreaties.

As time wore on, however, Biddle became increasingly alarmed at the fact that Jackson

was not coming over to his side. Biddle sincerely believed that Jackson’s antipathy towards

banks was a simple misunderstanding; once Jackson was in a position of power for an extended

period of time, surely he would see the positive role the Bank played in American society. Alas,

that was not the case; with each passing year, the President showed no signs of relenting or

changing his mind. When, in a speech, Jackson called for changes to allow state banks a larger

say in the system, Biddle flew into a rage, telling a colleague, “In respect to General Jackson and

Martin Van Buren, I have not the slightest fear of either of them, or both of them. Our country-

34 Ibid., 468.35 Ibid., 461.

20

men are not naturally disposed to cut their own throats to please anybody, and I have so perfect a

reliance on the spirit and sense of the nation that I think we can defend the institution from much

stronger enemies than they are.”36 Now fully believing in the American people, Biddle gave his

full support to pushing for a recharter four years early. Surely the people of the United States

would side with him.

Arguments Against, and the Veto

Jackson had intended the Second Bank of the United States to go quietly into the night,

similar to the way its predecessor had. Now that Biddle had decided to make an issue out of it,

Jackson was determined to fight for what he believed was right. In Jackson’s mind, the presi-

dency was the only position in the nation that represented the true will of the people. Congress-

men were elected to represent their districts; Senators were elected by state legislatures to repre-

sent their states; only the President, the Chief Executive, was elected by the whole of the people.

Thus so chosen by the electorate, and he was determined to execute their will (or at least his in-

terpretation thereof).

Jackson’s oppositions to the bank were primarily political and constitutional in nature. He

firmly believed that the Bank as an institution corrupted both the people in it and the country at

large. According to historian Sean Wilentz, “Jackson perceived that the Bank, by its very design,

undermined popular sovereignty and majority rule.”37 Additionally, the Bank concentrated power

in the hands of a few, small, unelected elite at the detriment to the masses. Even if, hypotheti -

cally, the Bank were well administered, such an enormity allowed, “‘a few Moneyed Capitalists’

to trade upon the public revenue ‘and enjoy the benefit of it, to the exclusion of many.’” 38 Con-

36 Ibid., 462.37 Sean Wilentz, Democracy in America, 253.38 Ibid., 253.

21

stitutionally, Jackson was Jeffersonian in his approach, advocating for a smaller, decentralized

government and a strict reading of the Constitution. That document granted no power to Con-

gress to charter a Bank, and as such, the Bank was invalid.

In a letter to John Randolph, one of his allies, Jackson thanked the aging statesman for his

support. Appealing to Randolph’s “Old Republican” mentality, Jackson wrote that the Bank “has

failed to answer the ends for which it was created, and besides being unconstitutional, in which

point of view, no measure of utility could ever procure for it my official sanction, it is on the

score of mere expediency dangerous to liberty, and therefore, worthy of the denunciation which

it has received from the desciples [sic] of the old republican school.”39 Here again, Jackson illus-

trates his concept of the Constitution; although the Bank might be useful overall to the Republic,

it is not constitutional, so it cannot be allowed to stand.

Some historians and economists claim that Jackson was simply appealing to the igno-

rance of the masses in attacking the bank; they claim that Jackson played on the anti-elitist fears

of the populace in order to further his own personal power and popularity. Others make the as-

sertion that Jackson simply did not know what he was doing and could not comprehend the im-

plications of his actions. Such statements reflect contemporary biases and cynicism towards

politicians rather than containing any revolutionary historical insight. Indeed, the historical

record belies these assertions. In an internal memorandum written in Jackson’s own handwriting

(an interesting document, as most writings for both internal and external dissemination were

composed by Andrew Jackson Donelson, Jackson’s nephew and private secretary), he elucidated

his reasons for opposing the Bank. Claiming the sovereignty for the Federal Government came

from the states and the people, Jackson asks rhetorically, “Is the sovereign power to grant corpo-

39 Andrew Jackson, Correspondence of Andrew Jackson (Volume IV), ed. John Spenser Basset (Washington D.C: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1929), 387.

22

rations expressly given to the general Government to be found in the constitution [sic], I answer

no….all powers not delegated are retained to the states and to the people…”40

Although, as discussed previously, the constitutionality of the Second Bank of the United

States had been established in the 1819 case McCullough v. Maryland, Jackson still held that the

Bank was unconstitutional. Addressing the Court’s statement that the Bank was a necessary ex-

tension of the function of government, Jackson wrote, “The powers of the Government are gen-

eral and national, not local. it [sic] must follow then that if necessity creates the power, then the

Bank must be exclusively national having no concern with corporations. it [sic] must be an ap-

pendage of the Treasury, a Bank merely of deposit and exchange.”41 Thus, although Jackson had

a personal antipathy towards the Second Bank of the United States, he would allow a national

bank to exist as long as it stayed within its constitutional boundaries as enumerated in Article I,

Section 8.

Jackson’s allies and associates rushed to his side. Thomas Hart Benton, Senator from

Missouri and one of the President’s right-hand-men, made an impassioned speech on the Senate

floor. After several attempts to silence him via parliamentary technicalities by the Bank’s allies,

Benton finally rose, and loudly stated, “Mr. President, I object to the renewal of the charter…be-

cause its tendencies are dangerous and pernicious to the Government and the people….It tends to

aggravate the inequality of fortunes; to make the rich richer and the poor poorer…”42 The Bank

benefitted the East at the expense of South and West; the bankers were enriching themselves on

the back of the honest, hard-working American: “Every body in the South and West knows that

the hard money of the country is disappearing; but only those who have observed the machinery

40 Ibid., 388.41 Ibid.42 Arthur Schlesinger, The Age of Jackson (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1946), 81.

23

of the Bank of the United States can tell where all this hard money is gone.” 43 Benton then fin-

ished with a crescendo:

In these mock sales of towns and cities may be laid the foundation for the titles and es-tates of our future nobility – Duke of Cincinnati! Earl of Lexington! Marquis of Nash-ville! Count of St. Louis! Prince of New Orleans! Such may be the titles of the bank no-bility to whom the next generation of American farmers must ‘crook the pregnant hinges of the knee!’44

Such rhetoric revealed the passions surrounding the Bank more than the workings and functions

of the Bank itself.

Newspapers inclined to favor the Administration’s policies also started writing editorials

criticizing the Bank. The Washington Globe, the official mouthpiece of the Administration, ex-

pressed anger at the corruption endemic to the institution: “We call the attention of our readers to

the article from the Washington Globe, on the first page of this paper, on the subject of the late

outrage committed by the United States Bank, in seizing a portion of the dividends on the gov-

ernment stock to cover the pretended damages claimed by it…This claim, amounting to 158,842

dollars and 77 cents has never been recognized by Congress, or by the Treasury Department.”45

According to the newspaper, this was not the first time such an event had occurred, noting, “We

must add this to the swelling list of unwarrantable acts committed by the Bank.”46 The Globe

dedicated several issues trying to galvanize public opinion, making several (not unwarranted)

claims that certain members of Congress were actually on the Bank’s payroll.

Despite the best efforts of Jackson’s allies in Congress, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster

were able to guide the Bank recharter Bill through, passing the Senate 28 to 20 and the House

107 to 85 about a month later on July 3. According to Jacksonian historian Robert Remini, the

vote to recharter the Bank, “reflected solid support for the Bank in New England and the Middle

43 H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, 466.44 Ibid., 467.45 The Globe, (Washington, DC) Monday, August 11, 1834; Issue 51; col E.46 Ibid.

24

Atlantic states, strong opposition in the South, and almost divided opinion in the Northwest and

Southwest.”47 Biddle couldn’t help himself; moments after the House passed the Bill, he made an

appearance on the floor, where “members crowded round to shake his hand. A riotous party in

his lodgings celebrated the victory late into the night.”48

Jackson was tremendously displeased at the news that the Bank’s proponents had suc-

ceeded in passing the bill to recharter the Bank; he had hoped it would simply die in Congress.

Martin Van Buren returned from England to find Jackson ill and in bed. Grabbing his friend’s

hand firmly, the President exclaimed, “The Bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me, but I will

kill it!”49 But Jackson would not stay ill for long. Within a few days, he gathered his closest advi-

sors (Van Buren, Amos Kendall, Roger Taney, and Andrew Jackson Donelson) together to work

on a draft of the message that would accompany the veto. After three days of work, the President

issued his veto on July 10, 1832.

The veto message “burst like a thunderclap over the nation.”50 The message, directed

more at the people of the United States than to the Congress to whom it was addressed, outlined

the Jacksonian interpretation of the Bank issue. The constitutionality of the Bank was once again

brought into question. Although the Supreme Court had already spoken to the Bank’s legitimacy,

the President disagreed with their assertions. For one, although McCulloch was the most famous

of the cases regarding the Bank, the Court had shifted a tad in their interpretation, twice support-

ing the Bank and twice opposing it. Additionally, the crux of the Court’s argument was that the

Bank was “necessary and proper” extension of the Federal Government. “It can not be ‘neces-

sary’ or ‘proper’ for Congress to barter away or divest themselves of any of the powers vested in

47 Robert Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Bank War (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1967), 80.48 Arthur Schlesinger, The Age of Jackson, 87.49 Martin Van Buren, The Autobiography of Martin Van Buren, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920), 625.50 Arthur Schlesinger, The Age of Jackson, 90.

25

them by the Constitution to be exercised for the public good,” Jackson argued; Congress had

done exactly this when they gave the Bank control over the currency, a power granted only to

Congress itself.51

Furthermore, the President did not believe that the Executive Branch was bound by the

decisions rendered by the Supreme Court. To later generations, such sentiments seem, well, bla-

tantly unconstitutional. Although Marbury v. Madison had established the precedent of judicial

review, such an idea was not universally held during Jackson’s time. Thus, “if the opinion of the

Supreme Court covered the whole ground of this act, it ought not to control the coordinate au-

thorities of this Government. The Congress, the Executive, and the Court must each for itself be

guided by its own opinion of the Constitution. Each public officer who takes an oath to support

the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by

others.”52 Since Jackson believed, according to his interpretation of the Constitution, that the bill

presented before him violated it, it was his job, and his duty, as Chief Executive to veto it.

The President also appealed to populist sentiments in his veto message. Congress had

granted the Bank monopoly status, which it used for its own advantage to the detriment of the

people. The government appointed only five of the twenty-five directors of the Bank; how could

such an institution, with a responsibility to is shareholders, be expected to put the nation ahead of

its own interests? Worst of all, a large portion of the Bank’s stock was in the hands of foreign in-

vestors, the consequences of which could be dire: “will there not be cause to tremble for the pu-

rity of our elections in peace and for the independence of our country in war? Their power would

be great whenever they might choose to exert it.”53 Jackson believed he would be violating his

51 Andrew Jackson, “Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States.” The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ajveto01.asp.52 Ibid.53 Ibid.

26

oath of office if he were to put the national security of the United States in the hands of non-

Americans.

The veto ended with Jackson’s larger vision for democracy: “It is to be regretted that the

rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” Jackson

wrote. However, he would not use that same government to level the playing field. “Distinctions

in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of

wealth can not be produced by human institutions.”54 All men are entitled to equal protection un-

der the law but, “when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial

distinctions,…to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of so-

ciety–the farmers, mechanics, and laborers–…have a right to complain of the injustice of their

Government.”55

Businessmen, members of Congress, and others who supported the Bank were shocked

by the Bill’s tone and language. Interestingly, Biddle was actually delighted at the veto message,

for he believed that the American people would be appalled by Jackson’s arrogance. In a letter to

Henry Clay, Biddle called the veto message, “A manifestation of anarchy, such as Marat or

Robespierre might have issued to the mob of the faubourg Saint Antoine.”56 Although attempting

to maintain an air of neutrality as the Bank’s President, privately, he now donated to Clay’s cam-

paign and wrote to the presidential candidate, saying, “You are destined to be the instrument

of…deliverance, and at no period of your life has the country ever had a deeper stake in you. I

wish you success most cordially, because I believe the institutions of the union are involved in

it.”57

54 Ibid.55 Ibid.56 Nicholas Biddle, The Correspondence of Nicholas Biddle dealing with National Affairs, ed. Reginald D. McGrane (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919), 196.57 Ibid.

27

But the veto served the exact purpose Jackson intended; in addition to explaining his rea-

sons for opposing the Bank, it unified the various factions of the Jacksonian coalition. For work-

ing men and the West, there were passages that tore into the Bank’s monopoly privileges. For the

moderates, Jackson left the door open for future debate when he stated that a National Bank

could be useful for the people. For the state banks and the states-rights Southerners, there was

Jackson’s claim that he would not allow a bank to subvert the rights of the states or the people. 58

In the words of historian Arthur Schlesinger, “The war against the Bank thus enlisted the enthu-

siastic support of two basically antagonistic groups: on one hand, debtor interests of the West

and local banking interests of the East; on the other, Eastern workingmen and champions of the

radical Jeffersonian tradition.”59 When Congress failed to override the veto, Jackson could finally

claim success.

Clay, Webster, and Arguments for the Bank

The two men who had led the debate in Congress for the Bank’s rechartering were two

political giants: Henry Clay, Senator from Kentucky, former Speaker of the House, and current

candidate for the presidency; and Daniel Webster, the current Senator from Massachusetts.

A wave of popular democracy was sweeping the country, but there still existed a class of

individuals and politicians steeped in Hamiltonian ideas and tradition. These politicians, led by

Henry Clay and the National Republicans (later the Whigs) still believed firmly in Clay’s Ameri-

can System, of which the Bank was a part. The Bank, Clay argued, allowed for credit to be more

easily accessible to those who needed it. By providing a uniform national currency rather than a

58 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy, 264.59 Arthur Schlesinger, The Age of Jackson, 79.

28

haphazard amalgamation of state currencies, the Bank also acted a guarantor of financial stabil-

ity; citizens would no longer have to worry whether the notes at their bank would be accepted by

those of another state, or how heavily those same notes might be discounted. The Bank, having a

much greater amount of capital in reserves, was able to loan out larger sums of money to corpo-

rations and businesses, which in turn spurred further growth. The institution also acted as the

government’s official bank of deposit, which kept the government’s funds safer than they would

have been if they were placed in dozens of state banks. Although the Bank had the unintended

consequence of concentrating wealth in certain areas, overall, it would be serving the best inter-

ests of the American people by providing them with sound currency, easy credit, and financial

stability.

After Clay had convinced Biddle to push for the Bank’s recharter, Daniel Webster led off

for its supporters in the Senate. “A disordered currency is one of the greatest of political evils,”

he claimed. “Of all the contrivances for cheating the laboring classes of mankind, none has been

more effectual than that which deludes them with paper money.”60 Seizing on the spirit of the

times, Webster made the democratic case for the Bank. If each state bank were permitted to print

their own currency, the rich could manipulate the lack of a consistent discount to their advantage.

Said Webster, “Ordinary tyranny, oppression, excessive taxation: these bear lightly the happiness

of the mass of the community, compared with the fraudulent currencies and the robberies com-

mitted by depreciated paper.”61 The lack of a sound currency hurt the poor much more than the

rich, and only a central bank could provide the sound, uniform currency the country needed.

The interesting aspect about Webster’s argument, as historian H.W. Brands notes, is that

the exact same argument, word for word, could be used by the opponents of the Bank.62 The crux

60 H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, 465. 61 Ibid., 465.62 Ibid., 464.

29

of Webster’s argument was that the Bank of the United States served as a check on state banks,

which, lacking coordination, produced run-away inflation. This was indeed true. However, the

Jacksonians pushed this argument further: if paper money was the culprit, why not just eliminate

all banks? Hard money (gold and silver) could check inflation just as well as a central bank

could, perhaps even better. Why not use gold and silver instead of a corruptible institution?

But Webster was not done. The day after Jackson issued his veto message, Webster made

an impassioned speech from the Senate Floor. Decrying the veto, Webster declared that the end

of the Bank would spell the end of a prosperous economy. “Thirty millions of the capital of the

bank are now out on loans and discounts,” Webster stated. “Now, Sir, how is it possible that this

vast amount can be collected in so short a period of time without suffering, by any management

whatever?” the Senator inquired.63 He called many of the President’s arguments baseless, stating

that taken to their logical conclusion, they could be used to attack any legal corporation. The

President was also disregarding decades of precedent by declaring himself on equal footing with

the Supreme Court as arbiter of the nation’s laws, thus turning the United States into a govern-

ment of men, not of laws. “If the opinions of the President be maintained,” the Senator argued,

“there is an end of all law and all judicial authority.”64 It appealed to the worst in men, stirring up

class antagonisms unnecessarily. The veto message appealed to public freedom, but in the eyes

of Webster, “nothing endangers that so much as its unparalleled pretenses.”65 Should Jackson’s

veto message be accepted by the majority of Americans, it would mean the end of the Republic.

Webster’s opponents accused him of engaging in an act of duplicity; after all, he had op-

posed the recharter of the First Bank of the United States back in 1816 when he was a Congress-

man. Many sensed that something more sinister was at hand; after all, until recently, Webster had

63 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 22.64 Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate, 211.65 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 30.

30

been on relatively friendly terms with the Administration. Unfortunately for Biddle, such accusa-

tions were more true than false. Webster had written a letter to the Bank President in December

1833 politely reminding Biddle that, “my retainer has not been renewed or refreshed as usual. If

it be wished that my relation to the Bank should be continued, it may be well to send me the

usual retainers.”66 When the Globe learned of this revelation, the editors quickly published it.

Webster was portrayed as Biddle’s little errand boy: “He had, it was reported, hurried from Phil-

adelphia upon the adjournment of Congress and received from the B.U.S. an easy loan of $10-

$15,000 for his services.”67 Although Webster had made salient points on the Senate floor in fa-

vor of recharter, his words were now dismissed as nothing more than mere rhetoric; one of the

Bank’s most ardent supporters had been effectively sidelined.

While The Globe, the official newspaper of the Administration, spoke highly of the con-

tent of Jackson’s veto message, the vast majority of newspapers around the country lambasted

the President. An editorial from the Portland Daily Advertiser, reprinted in the National Intelli-

gencer, reproached Jackson for the language used in the veto message. “There is no part more

deservedly reprobated and more reprehensible, than that part which attempts to array the poor

against the rich.”68 The Boston Daily Atlas called it the most radical document that had ever em-

anated from any Administration in any country, finding it incredulous that the President “un-

blushingly denies [that] the Supreme Court is proper tribunal to decide upon the constitutionality

of the laws!!”69 The Boston Daily Advertiser and Patriot screamed, “The spirit of Jacksonianism

is JACOBINISM….It’s Alpha is ANARCHY and its Omega is DESPOTISM.”70 The Lynchburg

Virginian accused Amos Kendall, one of Jackson’s closest advisors, of spreading lies about the

66 Nicholas Biddle, The Correspondence of Nicholas Biddle, 218.67 Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate, 211.68 George Rogers Taylor, Jackson Versus Biddle, 32.69 Ibid., 31.70 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy, 268.

31

Bank’s supporters: “Those who see the Washington Globe, are aware that Amos Kendall has

been for some past writing a series of Essays against the U.S. Bank, in the course of which he

has charged almost every distinguished advocate of that institution with having been bribed to

support it….Venal and corrupt himself, he cannot believe that other men are honest – and hence

he uniformly attributed the best actions to the basest motives...”71 While the Virginian acted gen-

uinely shocked that such accusations could be thrown around by the Administration, there was a

certain truth in Kendall’s statements: as many as two-thirds of the newspapers publishing pro-

Bank editorials were on the Bank’s payroll.

Some newspapers even attacked The Globe for supporting the President. The Daily Na-

tional Intelligencer, a newspaper that had supported the Republican Party of Jefferson, Madison,

and Monroe in years past now openly attacked the mouthpiece of the Administration. A few days

earlier, The Globe had run an editorial suggesting that should the Bank of the United States con-

tinue to function and be successfully rechartered, the nation would forever be beholden to Euro-

pean interests, as one of the members of the British Cabinet held stock in the Bank. In an edito-

rial on June 19, 1832, the Intelligencer mocked the editorial staff at The Globe for even suggest-

ing such a notion, saying, in part, “Such remarks are degrading to the government paper, and can

only be tolerated on the consideration that although they may disgrace the administration, they

will not be taken as conveying the sentiments of the American people.”72

Although ostensibly Biddle wanted the Bank to remain apolitical, he, by this point, enthu-

siastically supported Henry Clay, and many newspapers and politicians were on the Bank's pay-

roll. He had written articles in support of the Bank, and offered many newspapers monetary con-

tributions for publishing them. In a letter to a newspaper publisher, Biddle wrote, “For the inser-

71 Lynchburg Virginian. Thursday, November 1, 1832; Issue 22; Col A.72 Daily National Intelligencer, (Washington, DC) Tuesday, June 19, 1832; Issue 6042; col A.

32

tion of these I will pay either as they appear or in advance. Thus, for instance, if you will cause

the articles I have indicated and others which I may prepare to be inserted in the newspaper in

question, I will at once pay to you one thousand dollars.”73 Not wishing to be accused of any in-

discretions with the Bank’s money in the future, he also requested that the letter be returned to

him, “as it might be misconstrued.”74

The Election of 1832

Jackson’s supporters came together in May 1832 for the first ever Democratic National

Convention. The Convention nominated the sitting president unanimously and selected Martin

Van Buren as his Vice-President. The National Republican Party had already convened the pre-

vious December and nominated Henry Clay as their candidate for the Presidency. A third party,

the Anti-Masonic Party, also fielded a candidate: William Wirt. Andrew Jackson was indeed a

Mason, but many in the Anti-Masonic Party opposed Jackson for the same reasons the National

Republicans did.

The future status of the Second Bank of the United States (and by extension, Jackson’s

handling of the situation) was the issue of this presidential election. The only other point of con-

tention for the United States at this time was the Nullification Crisis; South Carolina, upset with

the new tariff passed by Congress, passed its own Orders of Nullification declaring that the tariff

was null and void in the state of South Carolina. However, both Jackson and Clay stood with the

Union and against the nullifiers, so this point was rendered moot.

The supporters of Jackson staged huge parades, raised hickory poles, and sang campaign

songs in support of their hero, General Jackson. Many threw barbeques, a few of which the Pres-

73 H.W. Brands, Andrew Jackson, 462.74 Ibid.

33

ident himself attended. Francis Blair oversaw massive printings and the nation-wide distribution

of The Globe, while Amos Kendall, de facto campaign manager, organized Hickory Clubs

around the nation in support of his candidate.75 Some of Jackson’s supporters were put on the de-

fensive in certain sections of the country (primarily New York and Pennsylvania, where the

Bank was most popular), much to Clay’s delight. However, in much of the rest of the nation,

Jackson’s stand against the Bank reaffirmed to the American people his support of the common

man over the rich and privileged. The Globe ran with this theme throughout the campaign,

declaring, “It is the final decision of the President – between the Aristocracy and the People – he

stands squarely by the People.”76

And the people stood squarely

with him. Jackson easily won re-elec-

tion, carrying sixteen of twenty-four

states and 219 electoral votes. Al-

though over 100,000 more votes were

cast in 1832 than in 1828, “Clay actu-

ally received 35,000 fewer votes than

John Quincy Adams had four years

earlier, a decline of nearly 7 per-

cent.”77 Jackson also broke the Na-

tional Republicans’ lock on New Eng-

land by winning both Maine and New Hampshire. Clay only carried his home state of Kentucky,

as well as Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maryland and Delaware; he could not even 75 Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy, 268.76 Ibid., 269.77 Ibid.

34

The results of the 1832 Presidential Election. Jackson won 55% of the popular vote and 219 electoral votes out of the 286 cast, easily winning re-election to a second term.

Image courtesy NationalAtlas.gov™

win the heavily pro-Bank states of Pennsylvania and New York. Clay and Biddle had thought

that the American people would clearly side with an institution both men believed served the

best interests of the nation; instead, they voted for their hero and against the “moneyed aristoc-

racy.” The vote vindicated Jackson and gave him the mandate he wanted against the Bank. His

overwhelming popularity and support led the defeated Anti-Masonic candidate, William Wirt, to

note “that he [Jackson] may be President for life if he chooses.”78

The War Rages On

Removing the Deposits

With his re-election secured, Jackson believed the American people had given him a

mandate to do what was necessary in regards to the Bank. Biddle, thoroughly shocked that Clay

had lost the election, assumed the same. With the Bank’s charter set to expire in 1836, there was

still one presidential election, one more opportunity for the Bank to survive. Both men assumed

the other would engage in some sort of chicanery to guarantee that their side emerged from the

Bank War victorious. Both were right.

Almost immediately after the election, Jackson began mulling over the decision to re-

move the Federal Government’s deposits from the Bank and place them in state banks. In the

words of historian Robert Remini, “His reasons for taking the action were obvious. To begin

with, he feared the Bank’s ability to utilize the three remaining years of the charter to upset the

verdict of the election and he wanted to reduce its power by denying it government funds.” 79 The

Bank received most of its operating revenue from using the Federal Government’s deposits, and

denying the Bank this money would severely impair its day-to-day functions and effectively

78 Robert Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Bank War, 107.79 Ibid., 111.

35

cripple it. When Francis Blair, one of Jackson’s advisors, told the President that Biddle would

actively be spending public funds to “frustrate the people’s will” by “using the money of govern-

ment for the purpose of breaking down the government,” Jackson became visibly irate, shouting,

“He shan’t have the public money! I’ll remove the deposits! Blair, talk with our friends about

this, and let me know what they think of it.”80

Over the summer of 1833, Jackson toured New York and New England. The heart of old

Federalist territory, Jackson was nonetheless greeted by the thunder of cannon, the roaring of

crowds, pompous reception committees and banquets galore. This reception confirmed to the

President his enduring popularity with the people, and provided him with the impetuous to do

what he considered necessary for the general welfare of Americans. Thus, when he returned to

Washington, he was committed to removing the Federal Government’s deposits. Unfortunately

for Jackson, the only individual who could initiate a removal of the government’s deposits was

the Secretary of the Treasury, William Duane, who refused. Additionally, Duane felt slighted by

Jackson, whom he felt did not respect his opinion, so he refused to resign. Jackson was a man

used to getting his way by now, so after a few days of terse negotiations, the President removed

Duane from his position and instilled one of his closet allies, the Attorney General, Roger Taney,

to the vacancy.

As soon as Taney assumed his new position, he appointed Amos Kendall as his agent to

identify which state banks would be the new depositories of government funds; Kendall picked

seven.81 On September 25, 1833, the order was issued from the Treasury Department: “com-

mencing October 1, 1833, all future government deposits would be placed in the state banks…

and that for operating expenses the government would draw on its remaining funds from the 80 Ibid.81 The seven banks were: the Union Bank of Maryland in Baltimore, the Girand Bank in Philadelphia, the Mechanics Bank of New York, the Manhattan Company of New York, the Bank of America in New York, the Commonwealth Bank of Boston, and the Merchant Bank of Boston.

36

BUS until they were exhausted.”82 These

seven “pet banks,” as they were dubbed by

the Administration’s opponents, increased to

twenty-two by year-end and to almost one

hundred within three years. By December 13,

1833, the public funds held by the Bank were

virtually gone.83 The Boston Post declared

the Bank, “BIDDLED, DIDDLED, AND

UNDONE.”84

But Biddle refused to sit by idly

while the President mercilessly tore apart his