Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Healthcare Facilities in...

Transcript of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Healthcare Facilities in...

Summary of Key Points

Standard indicators for facility-level WASH infrastructure do not adequately capture WASH accessibility

and use, and should be expanded to include routine provision of services

Limited availability of WASH services and unhygienic conditions in rural healthcare facilities in Rwanda

could impact expectant mothers’ decisions to seek delivery care at a healthcare facility

Regular external monitoring of specific WASH indicators is important for implementing WASH policies in

HCFs and sustaining improvements

Background

The World Health Organization and UNICEF have proposed an action plan as well as indicators for achieving

universal water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) coverage in healthcare facilities (HCFs). The indicators and targets measure access to improved water, improved sanitation, and handwashing stations with soap in all pa-tient care areas. However, investigation beyond access is needed to fully address the WASH in HCFs issue, as

access does not guarantee use. Patient and caregiver use of WASH services is critical for infection prevention control and reducing the risk of healthcare acquired infections (HCAI) to patients. Use of WASH services in

HCFs is largely unaddressed in many WASH in HCF service assessments. This brief describes the status and use of WASH services in 17 rural HCFs in Rwanda, using data from assessments performed at the HCFs to de-

termine the need and suitability of receiving a donated water treatment system (WTS). Data was collected in 2011 and results published in 2017.

The Study

Due to large investments in health system strengthening, Rwanda has been making serious health gains in popu-

lation health since the 2000’s seeing 60% and 63% declines in maternal and child mortality respectively, and 80% declines in deaths from HIV, TB and malaria. However, WASH in HCF in Rwanda is still a serious issue, as data from a World Bank assessment from 2007 found that only 28% of HCF in Rwanda had year-round water

supply, and only 58% had a functioning client latrine.

From 2011-2012, rapid screening and/or baseline assessments were completed in 17 rural HCF in Rwanda for the purpose of determin-

ing suitability to receive a donated water treatment system (WTS)

and to monitor the effects of the WTS on water quality and WASH

services. The results offer insight into the status of WASH in HCF in rural Rwanda. The study selected HCFs based on having access

to a piped water supply, regular power, and HCF leadership willing to participate in the study and receive the WTS. The assessments used water quality testing methods, direct observation, and HCF

staff interviews to assess drinking water quality and availability, WASH infrastructure, and WASH facility management.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Healthcare

Facilities in Rural Rwanda

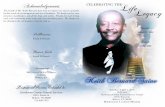

Patients and Caregivers Wait Outside

Healthcare Facility in Rwanda

Results

The HCFs were selected for this study based on the existence of WASH infrastructure that is able to support the

WTS, which is better than the average for rural HCFs in Rwanda, and therefore these results are not representa-tive of HCFs in rural Rwanda in general.

Drinking Water Quality and Availability On the day of the assessments, 15 of the 17 HCFs had running water from either a national utility (treated piped

surface water) or a local untreated source from a protected or unprotected well. Most HCF staff reported using piped water for drinking, and treating rainwater for drinking when piped water was unavailable. Staff at 15 of the

17 HCFs reported some type of point-of-use water treatment for drinking water (boiling, ceramic filter, chlorina-tion, or a combination), and two reported not treating drinking water at all. It was reported at all HCFs that, in general, treated drinking water was available to everyone, but it at all sites, it was observed that only 20L of treat-

ed drinking water per day was provided at the pharmacy.

WHO guidelines for safe drinking water state that there should be <1 E.coli/100mL and <1

total coliform/100mL for water to be consid-ered safe for drinking. WHO guidelines also

state that safe drinking water should contain ≥.02 mg/L of residual chlorine. Table 1 and

Table 2 below illustrate the percent of water samples collected during the assessment that met these standards. Many samples did not

meet the chlorine residual standard despite staff reporting that water is chlorinated.

Hand Hygiene Water available for hand hygiene was highly variable between patients, caregivers, and staff. Types of water ac-

cess points include tippy taps near latrines, sinks with taps, rainwater tanks with taps, and outdoor taps. More sinks with taps were reserved for staff than were available to patients and caregivers. Tippy taps were sometimes

empty, and sink taps were often removed or non-functional. Staff commonly reported intentionally removing taps to manage water use, or intentionally cutting of water supply to a leaky tap.

Soap was observed at very few handwashing stations. There were 119 working sink taps across all HCFs, and on-ly 33% had soap. Only two out of ten tippy taps and no outdoor taps had soap available. All HCFs had budget

allocation for providing soap and hygiene material, but staff reported that theft and misuse was an issue.

Toilets and Latrines All HCFs assessed had flush toilets or latrines available. The amount ranged from six to 15 toilets or latrines per

site, but overall, only two-thirds of toilets were in use, and only 53% of latrines were in a hygienic condition. At all HCFs, either a flush toilet or latrine was accessible to either staff or patients and caregivers. Flush toilets were frequently locked and designated for staff only; across all HCFs, 53% of toilets (18 out of 31) were available to pa-

tients and caregivers, the rest were designated for staff only.

Table 1: Water sam-ples meeting WHO standards for coli-forms

Met WHO Guide-lines for E.coli

Met WHO Guide-lines for Total Col-iforms

Tap water (N=20) 80% 15%

Drinking water (N=16) 93.75% 37.5%

Table 2: Water samples meeting WHO standards for chlorine

Met WHO Guidelines for Re-sidual Chlorine

Tap water (N=22) 40.9%

Drinking water (N=18) 61.1%

About the Center

The Center for Global Safe Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (CGSW) focuses on increasing access to safe drinking water, ad-equate sanitation, and appropriate hygiene as part of a global strategy to break the cycle of poverty and disease in developing

countries. For more information, please visit www.washconhcf.org or email [email protected]

Rollins School of Public Health

Emory University1518 Clifton Rd NE

Atlanta, GA, USA 30322

Staff Roles and WASH Monitoring All HCFs in Rwanda have a designated hygienist, who is responsible for

cleaning the facility, managing water use and treatment, and distributing soap throughout the facility. It was reported at all HCFs that records are not kept

which document these activities, but issues are reported to the hospital director as they arise. No HCF had tools or on-site capacity to service electrical sys-

tems and plumbing issues. Maintenance of these issues are contracted to out-side service providers, as well as the task of emptying pit latrines.

Across all HCFs in Rwanda, monitoring of WASH in HCF is done externally through the government’s Performance-Based Financing system. This system

performs quarterly observations of on-site piped water and drinking water in the pharmacy.

Lessons Learned

Standard WASH service delivery indicators do not fully capture access and use of WASH services by staff, pa-

tients, and caregivers. Although all HCFs had on-site access to piped water, toilets and latrines, and handwashing facilities, the reach of these services and the hygienic state of the sanitation facilities limited access and use, espe-cially for patients and caregivers. Monitoring of WASH in HCFs should include indicators that go beyond facility-

level infrastructure to include routine provision of services.

Previous studies have indicated that availability of adequate WASH services in HCFs may impact decisions to seek delivery care at a health facility, which could result in direct impacts on maternal and child survival. Even among

the HCFs assessed in this study, which displayed more robust WASH service availability than the average HCF in rural Rwanda, less than half of sanitation facilities were in a hygienic state.

The provision of treated drinking water in the pharmacy was observed consistently across all HCFs in the study, and had better performance than other factors assessed. The pharmacy drinking water was directly monitored by

the government’s Performance-Based Finance system. This illustrates the impact that a strong external monitoring system can have on achieving and sustaining improvements.

**This brief is a summary of the following research publication:

Huttinger, Alexandra, et al. "Water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure and quality in rural healthcare facilities in Rwanda." BMC

health services research 17.1 (2017): 517.

Pharmacy in Rwanda HCF with

Ceramic Water Filter