Walt Whitman (1819-1892) American Literature I 11/22/2004 Cecilia H. C. Liu.

-

Upload

keenan-rollison -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of Walt Whitman (1819-1892) American Literature I 11/22/2004 Cecilia H. C. Liu.

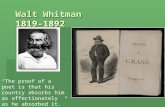

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

American Literature I 11/22/2004

Cecilia H. C. Liu

OutlineOutline

Introduction: Whitman and Leaves of Grass Whitman’s Song of Myself Whitman’s Portrays of Slavery in Song of

Myself (Critic’s comments) Whitman’s There Was a Child Went Forth Suggestive Readings Works Cited

Whitman and Whitman and Leaves of Leaves of GrassGrass

Walt Whitman is one of the 1st generation of Americans who were born in the newly formed US and grew up in the stable existence of the new country.

One of the haziest periods of Whitman’s life is the occurrence of the Civil War, when Whitman encountered casualties of the war. During this time, he visited wounded soldiers who moved to New York hospitals, and wrote about them in "City Photographs" published in 1862.

During the time of his hospital service, Whitman wrote about the war experience, but not the aftereffects, such as the moonlight illuminating the dead on the battlefields, the churches turned into hospitals, wound dressing, encountering with a dead enemy in a coffin, the trauma of battle nightmares for soldiers who returned home.

Whitman and Whitman and Leaves of Leaves of Grass (2)Grass (2)

Whitman paid for the production of the 1st edition of his book and had only 795 copies printed. The book appeared on the 4th of July, as a representation of literary Independence Day.

Whitman's book was an extraordinary accomplishment: after trying for over a decade to address in journalism and fiction the social issues (such as education, temperance, slavery, prostitution, immigration, democratic representation) that challenged the new nation).

Whitman expresses with the identification of a new American democratic attitude, that would make up the diversity of the country in a vast, single, unified identity.

"Do I contradict myself?" was a question Whitman asked confidently toward the end of the long poem "Song of Myself": "Very well then . . . . I contradict myself; / I am large . . . . I contain multitudes” Other Passages

Whitman & Whitman & Leaves of Grass Leaves of Grass (3)(3)

His work echoed with the language of the American urban working class and many corners of the 19th century culture, giving presentations in the nation's politics, its music, its new technologies, its fascination with science, and its evolving pride in an American language that formed as a tongue distinct from British English.

It is clear now the author of Leaves of Grass is Whitman, but Whitman did not put his name on the title page until the 1876 "Author's Edition" of the book..

Whitman & His Whitman & His InfluencesInfluences

Beyond poetry, Whitman has had an extensive and unpredictable impact on fiction, film, architecture, music, painting, dance, and other arts.

Whitman has enjoyed great international renown. Whitman’s importance not only presents from his literary qualities but also his standing as a prophet of liberty and revolutionprophet of liberty and revolution, since he served as a major icon for socialists and communists, who fulfilled promise of democracy.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of MyselfMyself

He shows suspicions of classrooms, with "Song of Myself" generated by a question a child would always ask, "What is the grass?" was defined in the 1st section.

In addition, the term of grass is one of the focus within the poem as he spends the rest of the poem with his discoveries of those seemingly simple, the cosmos in himself.

By the mid-1840s, Whitman began to show awareness of the cultural resources of New York City, and began dedicating himself to journalism. For Whitman, serving the public was to frame issues in accordance with working class interests, which is usually the white’s interests.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (2)Myself (2)

Whitman dreaded slave labor as a "black tide" that could overwhelm white workingmen. He believes that slavery should not be allowed into the new western territories.

Periodically, Whitman expressed outrage at practices that furthered slavery itself: for example, he was incensed at laws that made possible the importation of slaves by way of Brazil. Like Lincoln, he consistently opposed slavery and its further extension, even while he knew (again like Lincoln) that the more extreme abolitionists threatened the Union itself.

Whitman’s “There Was a Child Went Whitman’s “There Was a Child Went Forth”Forth”

Walt Whitman wrote more frequently about educational issues and always retained an interest in how knowledge is acquired.

One of the poems in his first edition of Leaves of Grass, eventually called "There Was a Child Went Forth," could be read as a statement of Whitman's educational philosophy.

He celebrates unrestricted extracurricular learning, and shows openness to experience and ideas that would allow for endless absorption of variety and difference, which was the kind of education he particularly valued.

Other Topics Whitman Other Topics Whitman AddressesAddresses

Whitman deals a lot about topics within Slavery, especially passages in Song of Myself, “The Sleepers,” and “I Sing.”

He also deals with Civil War, in Drum Taps, sex, in Calamus and Children of Adam, and the sea, in Sea-Drift.

Death is also mentioned quite a bit for Whitman, in his Drum Taps, with passages of the death of soldiers.

Other ExamplesOther Examples

New voice spoke confidently of union at a time of incredible division and tension in the culture, and it spoke with the assurance of one for whom everything could be celebrated as part of itself: "What is commonest and cheapest and nearest and easiest is Me" (Section 14).

This represents the new American spirit that Whitman intends to portrays.

Walt Whitman ImagesWalt Whitman Images

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (3)Myself (3)

"Song of Myself" portrays Whitman's poetic birth and the journey into knowing launched by that "awakening."

However, the "I" who speaks is not alone, since he has included the camerado, "you," addressed in the poem's second line, which is the reader, placed on shared ground with the poet throughout the journey.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (4)Myself (4)

The poem opens with the representation of the poet "observing a spear of summer grass""observing a spear of summer grass" and extending an extending an invitation to his soul, invitation to his soul, clearly prepares him for the soul's visit of section 5, a section that dramatizes the transfiguring event, launching the poet on his lifelong quest. Ex: section 1 and 2.

Awakening in section 5 prepared the poet for new knowledge, as he proceeds on the journey, and extends through section 32, where leads the poet to more subjects and themes addressed in Leaves of Grass.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself Myself

“Permit to speak at every hazard, / Nature without check with original energy" (Section 1).

Leaving "[c]reeds and schools" behind, he goes "to the bank by the wood to become undisguised and naked" (Sections 1 and 2).

He presents himself (section 13) as the "caresser of life wherever moving . . . Absorbing all to myself and for this song."

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (5)Myself (5)

After the grass imagery in section 6, Whitman moves to "en-masse,"en-masse," in 7-16.

The speaker, Whitman reveals, in forms of Whitman himself, American, roaming the continent, celebrating the scenes of ordinary life. Example: Section 13

Then, such movement rises in a crescendo to the extended catalogue of section 15, with exuberant snapshots of American types and scenes.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (6)Myself (6)

In sections 18-24, the poet collapses traditional discriminations, and celebrates "conquer'd and slain persons" (section 18) along with victors, the "righteous" the "wicked"—and extends his embrace to include outcasts and outlaws.

However, his focuses on the equality of body and soul and ways of rescuing the body from its inferior status.

He turns to himself and his own, and presents in section 24 a nude portrait of himself, with a metaphoric catalogue.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (7)Myself (7) In sections 18-32, the poet celebrates the erotic dimension

of all the senses, but he turns to a miraculous touch in section 28.

In section 33, it begins with higher affirmations of the 2nd part of the journey. The poet feels no longer bound by the ties of space and time, but feels that he is able to soar like a meteor out into space.

Hence, this peak of exaltation in section 33 switches to a tone to its opposite as the poet identifies with the rejected, suggests that he has moved obscurely beyond the knowledge of his previous phase in sections 17-20.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself Myself

"Is this then a touch? quivering me to a new identity?“ (Section 28).

"Space and Time! now I see it is true, what I guess'd at, /[ . . . ] when I loaf'd on the grass.“ (Section 33).

"I am the man, I suffer'd, I was there." He becomes the "old-faced infants and the lifted sick," the mother "condemned for a witch," "the hounded slave.“ (Section 33).

: "I discover myself on the verge of a usual mistake.“ (Section 38).

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (8)Myself (8)

Section 38 opens with strong rejection of the role of beggar he has assumed resets the direction for the poet on his journey. This stage, in which the poet is confident in his transcendent power, extends through the closing sections, 38-49.

In section 43 the poet affirms all religious faiths, and in section 44 he celebrates his place in evolutionary theory: both religion and science contain the seeds that provide the source for his supreme power.

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (9)Myself (9) In section 50 the poet seems to have

emerged from a trance-like state, similar to what he experienced in section 5

The "it" could refer to the transcendent meaning of Whitman’s experience on his dream-like journey. Example

Whitman addresses "brothers and sisters" first evoked in section 5, and includes a word that could convey some idea of the transcendent meaning on his journey. Ex

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of MyselfMyself "Wrench'd and sweaty--calm and cool then my body

becomes, / I sleep--I sleep long." Coming out of his deep sleep, the poet stammers almost incoherently: "I do not know it . . . it is a word unsaid, / It is not in any dictionary, utterance, symbol" (Section 50).

Something it swings on more than the earth I swing on, / To it the creation is the friend whose embracing awakes me" (Section 50).

"It is not chaos or death--it is form, union, plan--it is eternal life--it is Happiness." (Section 50).

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of Myself (9)Myself (9)

As the In the last two sections (51-52), Whitman addresses the idea of camerado from the beginning, "you," once more.

Whitman does not deny but dismisses his "contradictions, (see more), and describes himself "not a bit tamed,“and "untranslatable," His journey is over, he prepares for departure,as he return “to the dirt to grow from the grass", and says humorously, "If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles."

Whitman’s Song of Whitman’s Song of MyselfMyself

“I am large, I contain multitudes” (Section 50). On beginning his journey (section 1) he

promised he would "permit to speak at every hazard, / Nature without check with original energy."

At the end, the poet admonishes his readers to "keep encouraged" and continue their search for him, promising: "I stop somewhere waiting for you" (Section 52).

Portrayals of Slavery in Song of Portrayals of Slavery in Song of MyselfMyself

In section 10, Whitman addresses the runaway slave, and reminds us is the tremendous need for grammar in this world, the tremendous need for structural provisions unattached to particular persons, and responsive to all analogous persons.

Portrayals of Slavery in Song of Portrayals of Slavery in Song of MyselfMyself

Whitman portrays the African American in a sort of figure that one could identify and sympathize, such as the hunted figure in section 33 crucified by his pursuers and with whose passion the speaker identifies; and the figure of the black drayman in section 13, in command of his horses and himself.

Portrayals of Slavery in Song of Portrayals of Slavery in Song of MyselfMyself Another implication of the slaves could be seen in Section

11, the 28 bather, and in this passage Whitman encourages us to forget is the condition under which the slave is admitted, that they are trapped and unable to be let out, as one of its representative figures in his poetry.

Indeed, these figures--the trapper and his bride, and the bathing young men--must be forgotten as well. Thus, this reveals a sort of tender forgetfulness—that the 28 young men, bathers, do not realize that the woman had left her house and began to join in the dances and activities with them, touching them, because it is simply not registered as antecedence.

Suggestive ReadingsSuggestive Readings

Calamus (Sex) Children of Adam (Sex) Drum Taps (Death and The Civil War) Sea Drift (How Whitman Portrays the Sea) Memories of President Lincoln and Drum

Taps (Death and Memories in America) Specimen Days (Memories of Whitman)

Works CitedWorks Cited

The Walt Whitman Hypertext Archive. Ed. Folson and Kenneth M. Price. http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/whitman/

Miller, James E., Jr. “Song of Myself.”Ed. J.R. LeMaster and Donald Kummings. Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1998.

Whitman and Slavery Critical Positions. http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/fdw/volume1/price/positions.html