Walking, well-being and community: racialized mothers ...eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/4118/1/6. Walking well...

Transcript of Walking, well-being and community: racialized mothers ...eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/4118/1/6. Walking well...

Full Terms amp Conditions of access and use can be found athttpwwwtandfonlinecomactionjournalInformationjournalCode=rers20

Ethnic and Racial Studies

ISSN 0141-9870 (Print) 1466-4356 (Online) Journal homepage httpwwwtandfonlinecomloirers20

Walking well-being and community racializedmothers building cultural citizenship usingparticipatory arts and participatory actionresearch

Maggie OrsquoNeill

To cite this article Maggie OrsquoNeill (2018) Walking well-being and community racialized mothersbuilding cultural citizenship using participatory arts and participatory action research Ethnic andRacial Studies 411 73-97 DOI 1010800141987020171313439

To link to this article httpsdoiorg1010800141987020171313439

Published online 07 Jun 2017

Submit your article to this journal

Article views 219

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Walking well-being and community racializedmothers building cultural citizenship usingparticipatory arts and participatory action researchMaggie OrsquoNeill

Department of Sociology The University of York York UK

ABSTRACTCommitted to exploring democratic ways of doing research with racializedmigrant women and taking up the theme of ldquowhat citizenship studies canlearn from taking seriously migrant mothersrsquo experiencesrdquo for theory andpractice this paper explores walking as a method for doing participatory arts-based research with women seeking asylum drawing upon researchundertaken in the North East of England with ten women seeking asylumTogether we developed a participatory arts and participatory action researchproject that focused upon walking well-being and community This papershares some of the images and narratives created by women participantsalong the walk which offer multi-sensory dialogic and visual routes tounderstanding and suggests that arts-based methodologies using walkingbiographies might counter exclusionary processes and practices generategreater knowledge and understanding of womenrsquos resources in building andperforming cultural citizenship across racialized boundaries and deliver onsocial justice by facilitating a radical democratic imaginary

ARTICLE HISTORY Received 26 February 2016 Accepted 13 March 2017

KEYWORDS Walking mobile methods cultural citizenship racialized mothers participatory actionresearch social justice

Introduction

In the introduction to this special issue Erel Reynolds and Kaptani (2016)explore ldquothe everyday experiences of participation and belonging ofmigrant mothers in actively forming new understandings of community citi-zenship and political subjectivity against the grain of racialized practices ofsubjection and exclusionrdquo This paper contributes to this project by exploringwalking as a method of conducting research with migrant women drawingupon participatory research conducted with ten women in the North Eastof England some of whom are mothers and at the time of the researchwas either seeking asylum had refugee status [one woman] or were

copy 2017 Informa UK Limited trading as Taylor amp Francis Group

CONTACT Maggie OrsquoNeill MaggieoneillYorkacuk

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 2018VOL 41 NO 1 73ndash97httpsdoiorg1010800141987020171313439

undocumentedhad no recourse to public funds [their claim for asylum hadbeen refused]

The research used participatory arts (PA) and performative methods includ-ing walking photography and film Outcomes included a series of walks anexhibition a film1 and some co-produced articles These outcomes are uti-lized in this paper to explore the ways in which the women ldquowho are not citi-zens participate in the common social economic and political life of a specificstate and claim rights in these multiple domainsrdquo (Isin and Nielsen 2008) Theresearch is underpinned by the interrelationship between critical theory livedexperience and ldquopraxisrdquo (as purposeful knowledge) in documenting andunderstanding womenrsquos lives experiences and their senses of ldquobelongingrdquoas a dynamic process (Yuval-Davis 2006 OrsquoNeill 2010 Haaken and OrsquoNeill2014)

In walking with the women through a series of collective walks post walkworkshops and discussions knowledge and ldquounderstandingrdquo (Bourdieu 1996)is gained of womenrsquos experiences in space time and place (Heddon andTurner 2010) as well as their inter-subjective inter-corporeality (Dolezal2015) their struggle for recognition belonging as well as their ldquoenactmentsrdquoof cultural citizenship in the new situation By cultural citizenship (Pakulski1997) I mean the right to presence and visibility not marginalization theright to dignity and maintenance of lifestyle ndash not assimilation to the domi-nant culture and the right to dignifying representation ndash not stigmatization

This research builds upon the authorrsquos long history of doing PA and parti-cipatory action research (PAR) with groups and communities artists and com-munity arts organizations (OrsquoNeill 2010) and her use of walking as an arts-based practice and biographicalnarrative method (OrsquoNeill and Hubbard2010 Pink et al 2010 OrsquoNeill and Stenning 2014 OrsquoNeill and Perivolaris2015) The research contributes to the rich literature on PAR (Fals Borda1983 1987 Kindon Pain and Kesby 2007 Reason and Bradbury 2008) andracialized citizenship (Kabeer 2002 Erel Reynolds and Kaptani 2016) It alsocontribute to the developing field of mobilities research (Urry 2007Buscher Urry and Witchger 2011 Roy et al 2015 Smith and Hall 2016)However the use of walking as a biographical and phenomenologicalmethod2 was inspired by artists (as well as social scientists) as a way ofdoing arts-based biographical research The research was also influenced byfeminist and critical theoretical work on contested citizenship (Kabeer 2005Lister 2007 Lister et al 2007) social justice3 (Hudson 2006) the importanceof the imaginary domain (Cornell 1995) and the concept of a radical demo-cratic imaginary (Smith 1998)

In seeking to make sense of the migrant womenrsquos experiences bothpsychic and socialmaterial in performing and enacting citizenship thispaper claims that walking as an arts-based biographical research methodoffers a powerful route to understanding the lived experiences of women

74 M OrsquoNEILL

as well as the development of processes and practices of inclusion towards aradical democratic imaginary Indeed for the women participants walking inMiddlesbrough is a radical democratic act and performance For Cornell (1995)like Smith (1998) the imaginary domain is a moral and psychic space that isnecessary in order to open keep open and rework the repressed elementsof the social imaginary

Centrally the paper reflects upon how asylum seeking and undocumen-ted women creatively enact and perform citizenship through their everydaymobilities their attachments to place and space in Teesside and their situa-tional authority in guiding the collective walks At the same time it evi-dences how women contest or challenge hegemonic and racializedldquopractices of subjection and exclusionrdquo (Erel Reynolds and Kaptani 2016see also Kaptani and Yuval-Davis 2008) in both their experiences of livingin Teesside as well through their contributions and participation to thearts-based project

Committed to exploring democratic ways of doing research with migrantwomen and taking up the concept of women migrants ldquoenacting citizenshiprdquo(Erel 2013 Nair 2015) this paper shares the PA-based research conducted withten women seeking asylum in the North East of England and extends debateson visual walking and mobile methods cultural citizenship racialized citizen-ship belonging community and social justice for women seeking asylum inthe UK

Socio-cultural-political context

Women seek asylum for the same reasons as men as well as fleeing gender-based sexual violence Yet these gendered dynamics are an under examinedtopic (Nair 2015) The recent Immigration Act 2016 alongside a range ofrestrictions put into place mean that it is incredibly hard to gain refugeestatus in Britain if you do it is temporary and this increases vulnerabilityespecially for families (Mayblin 2015) Moreover the cultural and material land-scape of ldquoBrexitrdquo in the UK makes for a hostile climate for both new arrivalsand longer term migrants waiting for decisions on their asylum and immigra-tion claims

Recent migration surge in Europe Europeanization of restrictive asylumpolicy geopolitical changes what Bauman (2004) calls ldquonegative globalisa-tionrdquo EU enlargement ldquoBrexitrdquo and ldquoIslamophobiardquo have heightened secur-ity concerns about unregulated migration and porous borders In the UK aldquorace relations frameworkrdquo (Schuster and Solomos 2004) is central to thedevelopment of asylum policy and most people come to understand thelived experience of asylum exile and processes of belonging in contempor-ary western society through the mediated images and narratives of themass media

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 75

What is clear is that refugees and asylum seekers have become the folkdevils of the twenty-first century and overall mainstream media represen-tation of the asylum issue the scapegoating of asylum seekers and tabloidheadlines help to create fear and anxiety about the unwelcome ldquoothersrdquoand to help set agendas that fuel racist discourses and practices As Nagarajan(2013) argues ldquopoliticians and the press are locked in a cycle of increasing anti-immigrant rhetoric presented as lsquouncomfortable truthrsquo Yet the problem is notimmigration but socio-economic inequalityrdquo

Moreover Reynolds and Erel (2016) identified how migrant mothers aredemonized as ldquobenefit cheatsrdquo ldquohealth touristsrdquo and ldquowelfare scroungersrdquoThe ldquocultural diversity they embody rather than being celebrated is similarlyviewed in terms of constituting a potential threat to social and cultural cohe-sionrdquo despite the fact that they make a significant contribution to UK societyand ldquotheir cultural diversity can contribute to developing a future citizenrymore comfortable with culturally and ethnically plural identitiesrdquo

The broader conflict at the centre of western nationsrsquo responses to theplights of asylum seekers and refugees is seen in the changing responseto migration surge in the Mediterranean alongside a commitment toHuman Rights and the 1951 Convention in the UK and on the other handpowerful rhetoric aimed at protecting the borders of nation states under-pinned by the message ldquoGo Homerdquo or ldquostay outrdquo as states lock down theirborders and more recently in the mobs attacks on refugees in Stockholm(Osborne 2016) and the English Defence League marches in Dover(Sommers 2016)

The movement of people across borders is a key defining feature of thetwentieth and twenty-first centuries In Matthias Kispertrsquos film No MoreBeyond (2015) one of his interviewees who had walked to the Melilla crossingfence asks ldquoWhat is the legal way to immigrate Why donrsquot they give me thisoption I am illegal because there is no legal routerdquo

Arendt (1998) identified ldquothe twin phenomena of lsquopolitical evilrsquo and lsquostate-lessnessrsquo as the most daunting problems of the twentieth and twenty-firstcenturyrdquo (Benhabib 2004 50) Statelessness for Arendt meant loss of citizen-ship and loss of rights indeed the loss of citizenship meant the loss ofrights altogether ldquoOnersquos status as a rights-bearing person is contingentupon the recognition of onersquos membershiprdquo and ldquoIn Arendtian language theright of humanity entitles us to become a member of civil society such thatwe can then be entitled to juridico-civil rightsrdquo (Benhabib 2004 59)

Benhabib (2004) acknowledges the bifurcation between on the one handuniversal human rights and on the other the right of state protection andthat the nation state system carried ldquowithin it the seeds of exclusionaryjustice at home and aggression abroadrdquo (61) Thus the conflict between univer-sal human rights and sovereignty claims are ldquothe root paradox at the heart ofthe territorially bounded state-centric international orderrdquo (Benhabib 2004 69)

76 M OrsquoNEILL

This is documented very clearly in the work of Tastoglou and Dobrowlesky(2006) who discuss the ldquoglobal realities that stem from the intricate interplayof gender migration and citizenship and the inclusions and exclusions thatresult under specific conditionsrdquo (Tastoglou and Dobrowlesky 2006 4) Fordespite the right to seek asylum being a human right as both Benhabib(2004 69) and the current responses to migration surge across Europe illus-trate ldquothe obligation to grant asylum continues to be jealously guarded bystates as a sovereign principlerdquo Not having onersquos papers in order being undo-cumented sans papiers is a form of social death that brings with it ldquoquasi crim-inal statusrdquo a curtailment of human rights and no civil and political rights ofassociation and representation (Benhabib 2004 215)

For Benhabib ldquothe extension of full human rights to these individuals andthe decriminalisation of their status is one of the most important tasks of cos-mopolitan justice in our worldrdquo (2004 168) Concepts of what constitutes citi-zenship and also social justice is vital in addressing these issues andinequalities and can be explored through processes and practices of exclu-sion and inclusion

It is within this precarious social political and cultural context that asylumseeking women perform acts of cultural citizenship that are not just aboutrights and obligations but about negotiating belonging and as Lister et al(2007 9) drawing upon Fraser (2003) states ldquoan important element of belong-ing is participationrdquo Moreover for Lister et al (2007 10) citizenship is experi-enced across a number of levels ldquofrom the intimate through the local nationaland regional to the global where it is sometimes represented in the languageof cosmopolitanism and of human rightsrdquo Referencing Jones and Gaventa(2002) Lister et al (2007) describe how such multi-layered understandingsof citizenship need also to be concerned with the ldquoconcrete lsquospaces andplacesrsquo in which citizenship is practicedrdquo as an ldquoidentity and practicerdquo

ldquoWomen well-being and community in Teessiderdquo

In Ministry of Justice funded work in the North East the North East RegionalRace Crime and Justice network undertook research across the three NorthEast police force areas (Durham Northumbria and Cleveland) on RaceCrime and Justice in 2011ndash12 (Craig et al 2012)4 One emerging issue wasthe need to focus on womenrsquos specific experiences as migrants asylumseekers and refugees in relation to community and well-being Togetherwith the regional refugee forum North East (RRFNE) and a womenrsquos groupldquoPurple Rose Stocktonrdquo Maggie OrsquoNeill Janice Haaken and Susan Mansaraydeveloped a PA and PAR project that focused upon womenrsquos lives and well-being in order to better understand asylum seeking refugee and undocu-mented womenrsquos experiences of living in Teesside (which has the largest dis-persal of asylum seekers in the North East) challenge and change racial sexual

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 77

and social inequalities stimulate arts-based outcomes to share across a widerpublic and impact upon policy and praxis

The ten women who participated were from Africa Asia and the MiddleEast and included teachers nurses mothers a former MBA student and a jour-nalist They were all situated in the asylum migration community nexus(OrsquoNeill 2010) and most were living in refugee housing provided by a localhousing provider JomastG4S Some were fleeing gender-based violenceand others were claiming asylum based upon their precarious political situ-ations as former activists some arrived with families and others had left chil-dren behind when the time came to flee During the project one youngwoman was detained sent to a detention centre and was subsequentlyreturned to her home country this was devastating for her and for thegroup We were thirteen women in total ndash ten of whom were womenasylum seekers a UK-based artist and two women academics (UK USA)5

The arts-based research involved conducting a critical recovery of thewomenrsquos lives journeys and histories using walking methods storytelling bio-graphical participatory and visualphotographicfilmic methods We soughtto make visible womenrsquos lives in Teesside their connections and attachmentsto places and spaces in the city their lived experiences and issues as well assharing what community and community safety means to them with thewidest possible audience by exhibiting some of this work through talks a tra-velling exhibition and a film

Susan Mansaray a community co-researcher on the project and founder ofPurple Rose Stockton a community organization supporting the health andwell-being of migrant women at the launch of the exhibition said ldquothisproject depicts what women seeking asylum go through on a daily basis Ifas a result of this project one individualrsquos mind and perception towardsasylum seekers will change then we have achieved somethingrdquo

OrsquoNeill (2011 2012a 2012b 2013 2014) has argued that ldquoarts-basedresearchrdquo ndash the production and analysis of visual poetic narrative and perfor-mative texts and the stories people tell about their lives ndash facilitates sensuousunderstanding of society and the complexity of the lives of migrants Thisprocess is defined as ldquoethno-mimesisrdquo drawing upon the work of Adornoand Benjamin on mimesis and the relationship between art and society andarts-based ethnographic research

Listening to the experiences of people seeking safety using ethnographicbiographical and artistic methods and focusing attention upon the micrologyof lived experience ndash the minutiae the small scale ndash we can often reach abetter understanding of the larger picture As Adorno said ldquothe splinter inyour eye is the best magnifying glassrdquo (Adorno 1978 50) meaning that focus-ing on the ldquomicrologyrdquo of lived experience can often shed light on broaderstructures relationships discourses and processes that are not only theoutcome but the medium of social action and meaning making

78 M OrsquoNEILL

The workshops and meetings took place in the RRFNE premises in Middles-brough In the first workshop following introductions and an open discussionabout how we might organize the project women were asked to draw a mapfrom a place they call home to a special place6 marking the places and spacesalong the way that were important to them We then discussed the maps witheach woman talking us through her map routes and landmarks In the processit was clear that many of the issues spaces and places were common to thewomen and that they wanted to take us on a collective walk to show us theirMiddlesbrough The walks took place over three days using the maps that thewomen had produced singularly and then collectively documenting theplaces and spaces in the city that are important to them both safe zonesand danger zones places of comfort belonging and also community

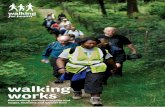

During the walks we stopped at places the women wanted to share with usto converse see tune in listen record photograph and film the route and theplaces spaces and stories shared along the way about their senses of commu-nity well-being belonging and becoming citizenship In the participatoryprocess a collective story emerges in the context of their lives in Teessidein ldquosituational authorityrdquo they shared their stories (Figure 1)

Walking methods why walking

Through ldquowalking biographiesrdquo and visually representing the walks we wereable to get in touch with womenrsquos ldquorealitiesrdquo in sensory inter-subjective andinter-corporeal ways ndash that fostered ldquounderstandingrdquo7 (Bourdieu 1996) and

Figure 1 Women walking

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 79

critical reflection particularly when walking with groups who are marginalizedand racialized such as asylum seeking women OrsquoNeill (2014) argues that thecorporeal and sensory engagement involved in walking together necessarilyinvolves reflection on ways of knowing and understanding in biographicalresearch and shared narratives of belonging and participation As we willsee in the next section walking with women helps to identify in a corporealand affective way the ldquoconcrete lsquospaces and placesrsquo in which citizenship ispracticedrdquo as an ldquoidentity and practicerdquo (Lister et al 2007 10)

Combining participatory biographical and visual research and ldquowalkingrdquocan open a shared space an imaginary domain (Cornell 1995) generatesensory knowledge and shared ldquounderstandingrdquo about belonging and citizen-ship and in the process facilitate creative and transformative impact on thepeople situation environment and policy terrain through the researchprocess findings and outputs The policy relevance of the method is impor-tant given the socio-cultural context outlined above

There is a long tradition of walking in ethnographic and anthropologicalresearch (Ingold and Lee-Vergunst 2008 Pink 2008 Edensor 2010 Irving2010 Radley et al 2010) but not in biographical sociology (OrsquoNeill 2014) orfeminist research with migrant women Clark and Emmel (2010 1) in a UK-funded community study discuss walking interviews as a way of understand-ing how their participants ldquocreate maintain and dissemble their networksneighbourhoods and communitiesrdquo

In this research with women asylum seekers we moved beyond the notionof ldquowalkingrdquo as a method discussed by ethnographers planners and anthro-pologists that helps us understand how space and place is made and usedhow neighbourhoods are formed re-formed and sustained towards the crea-tive application of this mobile method as a deeply engaged relational way ofldquoattuningrdquo (Scheff 2006) to the life of the women that evokes knowing andldquounderstandingrdquo through ldquoempathicrdquo and ldquoembodied learningrdquo (Pink 2007245) to help us access the way that citizenship is enacted and performed phe-nomenologically as well as materially in the lived experiences and narrativesof the women who participated

In the process of walking we becoming ldquoattunedrdquo to the women we seethe spaces and places the city through their eyes and walking togethercan advance connection dialogue active listening and understanding Inthis way walking as an embodied research practice and process is relationaldiscursive and reflective (OrsquoNeill Roberts and Sparkes 2014) Importantly it isalso sensory and multi-modal it facilities multiple modalities of experienceand inter-subjective inter-corporeal connection recognition and understand-ing experienced in the sensory entanglements that occur when walking

As Solnit states ldquowalking shares with making and working that crucialelement of engagement of the body and the mind with the world ofknowing the world through the body and the body through the worldrdquo

80 M OrsquoNEILL

(Solnit 2001 29) Thus it is a broad sensory and knowing experience whichincludes being or consciousness and phenomenological understandingIndeed walking for most of us is integral to what De Certeau (1984) callsan ldquoeveryday practicerdquo the practices and experience of everyday life(Edensor 2010 Pink et al 2010 2)

Together we researched and documented the sensory embodied inter-subjective stories and sensory modalities that are elicited when walkingwith migrant women ndash and in doing so challenge racialized hierarchiesmyths and stereotypes about asylum and migration and provide an opportu-nity to explore the ways that women perform and enact citizenship in anemergent relational way

For Haaken and OrsquoNeill (2014 84ndash85) from a biographic and psychoanalyticperspective the use of walking with this group of women

centers as much on connecting with womenrsquos lived experiences through the eth-nographic visual biographical methods imagining ndash of creating and improvis-ing a holding space for narratives of experience memory poetry movementand imagery to emerge ndash rather than discovering an already-there environment

Using participatory methods working with women as co-researchers wesought to tell a story of women asylum seekers as complex and activeagents in navigating the city and ever mindful of our potential as researchersto collude in the persecutory apparatus of the State even in our attempts toldquobear witnessrdquo to lives lived precariously on the margins We suggest thatcombining psychoanalytic-feminist theory and visual-ethnographic methodsndash walking biographical interviews ndash widens the critical space for re-imaginingmigration even as working in the hyphens these in-between spaces and thusdestabilizes efforts to arrive at simple truths

Extending this further performance artist Myers (2010 59) describeswalking as the ldquothe art of conversive wayfindingrdquo and part of this involvesldquointeracting with and knowing placerdquo through

kinaesthetic synesthetic and sonethestic perception sharing ldquoearpointsrdquo andldquoviewpointsrdquo with another through intimate or conversational conviviality useof present tense and the tension between the real-time present and a pastpresent and the use of particular rhythmic structures and narrative paces andpaths to encourage experiential creative and critical states of witness

Using walking to conduct biographical research draws upon the ldquoinventivequalities of walkingrdquo (Fulton 2010 8ndash12) that elicits phenomenologicalpsycho-social biographical understanding experienced through inter-subjec-tive recognitions

Walking with the women through Teesside reminds us of what Ingold andLee-Vergunst (2008 97) describe as knitting together ldquotime and placerdquo andthat walking is a narrative process that weaves together time and spacerdquobringing past present and future time together Through walking ldquoconversive

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 81

wayfindingrdquo through attuning and connecting we can experience discoverand interpret the process and practices of womenrsquos attempts at performingand enacting citizenship

Performing cultural citizenship

There are two broad senses in which the walks we undertook facilitate oruncover the performance of cultural citizenship First the collective walkwas a performanceperformative intervention in and of itself in the grouprsquostaking hold of space and moving collectively through various public andprivate spaces streets and buildings in Middlesborough The very processand performance of taking a collective walk and stopping to engage withcertain places buildings and spaces as a group of asylum seeking womenchallenges racialized hierarchies of subjection and exclusion particularly inpublic spaces

Middlesborough is a stronghold of the English Defence league in the NorthEast and a city marked out by high indicators of poverty and deprivation andonly recent experience of in-migration from asylum seekers dispersed to theavailable housing stock in the poorest areas Given the demise of racial equal-ity councilrsquos and the closure of regional government offices the developmentof refugee community organizations takes place in an austerity landscapewhere the RRFNE (based in Middlesbrough) since the reduction of theNorth East Refugee Service (NERS) provides a collective focus support andvoice for refugee communities in the North East Research in the region docu-ments the harsh realities of racism incivilities prejudice and discriminationexperiences by asylum seekers and BME communities (Craig et al 2012Donovan MacDonald and Clayton 2014 Littler and Feldman 2015)

The collective walks we undertook claimed a women-centred space andwere a visible marker of and challenge to exclusionary processes and practicesdirected towards women asylum seekers ndash walking together through thestreets park library shopping centre solicitors offices community cafesfood bank Teesside University education support organizations and thepolice station ndash highlighted the articulation of womenrsquos right to publicspace the right to support for their asylum claims and an articulation of cul-tural citizenship as belonging ndash the right to presence and visibility and theright to dignifying representation The women also expressed feeling agreater sense of belonging and connection by walking in a group somealso felt safer in doing so ndash their right to space enhanced and reinforced inthe collective

Second in the sense that the ethnographic biographical and performativewalks made visible womenrsquos acts of citizenship that Isin and Nielsen (2008 4)discusses ldquoActs of citizenship create a sense of the possible and of a citizen-ship that is lsquoyet to comersquordquo These are the acts where ldquosubjects constitute

82 M OrsquoNEILL

themselves as citizens or better still the right to have rights is duerdquo (Isin andNielsen 2008 2) The emphasis is on the ldquoactsrdquo or ldquodeedsrdquo not the subjects

The articulation of womenrsquos biographical experiences in both public andprivate spaces is vitally important to the development of dialogue a recogni-tive theory of social justice and cultural citizenship particularly when thevoices of migrants are mediated by others notably the mainstream pressand media and the dominant image of an asylum seeker is of a young manbreaking into Britain

This research uncovered the womenrsquos experiences and hidden historiestheir feelings of loss at leaving loved ones and separation from home theirescape from violence and trauma female genital mutilation and sexual anddomestic violence their acts of political resistance and subsequent need toflee The space for democratic contestation and performative citizenshipwas also facilitated through the combination of biography and art makingcreating a potential space for visualizing their stories that might lead to under-standing that challenges myths and stereotypes about women as ldquoscroun-gersrdquo and ldquowelfare recipientsrdquo (Reynolds and Erel 2016)

Grossman and OrsquoBrien (2011 54) argue that participatory media (film pho-tography digital storytelling and also radio) can foster a space to help articu-late ldquodiverse immigrant voicesrdquo In their work with new immigrantcommunities in Ireland they highlight the tension and dialectic between aldquopolitics of voicerdquo and a ldquopolitical listeningrdquo Noting the challenges of partici-patory media they state that there is a ldquoprecariousnessrdquo in the spacebetween ldquovoicerdquo and ldquolisteningrdquo alongside ldquounderstandingrdquo and ldquocomprehen-sionrdquo underpinned by ldquosystemic unequal and social power relationsrdquo

Acknowledging this precarity in performing and enacting citizenship theresearch and visual and filmic texts shared below help to open and keepopen spaces for resistance reflection and dialoguediscussion (evokingboth voice and listening) an imaginary domain a radical democratic imagin-ary marked by the principles of social justice as discursiveness relationalismand reflectiveness (Hudson 2006) in sharp contrast to the asylum seekers asa ldquonegative Otherrdquo (Hudson 2003 103)8

A core group of women worked with the researchers to choose the exhibi-tion images create the exhibition booklet create broadcast quality sound filesof one of the women reading her poetry (her work articulates the complexfeelings and experiences of doing cultural citizenship and plays a large rolein the film produced by Janice Haaken in collaboration with the group) andsupport the exhibition as it travelled to community venues and conferences

The importance of doing research in participation with the very peoplesituated in the asylum migration community nexus cannot be overstated inorder to ndash uncover hidden histories ensure space for democratic contestationand thinking through citizenship as performative Enhanced by creativemethods that combine ethnography and art making and in this case

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 83

walking and visual methods creates a potential space for re-thinking theconcept of cultural citizenship and women as enacting citizenship in theldquomargins of the marginsrdquo (Agamben 1995)

An overarching theme of the walks was the womenrsquos search for asylum Weused this as the title of the film Searching for Asylum Within this overarchingtheme the following themes emerged in the walks the importance ofwomenrsquos storytelling capacities to move official listeners their self-determi-nation and agency in the search for freedom and the material spatialemotional and symbolic barriers they face accommodate andor overcomethe importance of recognition and the relational sense of belonging in thetransnational and often temporary spaces they inhabit sometimes expressedas solidarity

Womenrsquos storytelling capacities

In Figure 2 the women are gathered around a local solicitors office All of thewomen had the solicitor on their map and this was an important place in theircollective story

This is very important for without a solicitor your asylum claim will not go any-where I remember when I first came to Stockton and my asylum claim wasrefused and my solicitor was very supportive When you have one who is sup-portive it helps a lot When I was refused I was very depressed and she talkedto me like a friend giving me assurance and support That meant a lot Solicitorsare like doctors some can make you better and some cannot (Mo)

Figure 2 Sharing a walk as a performative intervention and empathic witnessing

84 M OrsquoNEILL

Womenrsquos claims for asylum rest on the power of their stories especially ifthey no longer have or were forced to flee without the documents requiredfor their claim ldquoFinding a solicitor to take your case and move it forward isvery importantrdquo

Self-determination and agency othering and resisting ldquoracializedpractices of subjection and exclusionrdquo in seeking citizenship

The imagined community (Anderson 1991) of the nation state and the sover-eign right to exclude is operationalized and embedded in the UK in law andorder politics and discourses on immigration and race relations policy (Schus-ter and Solomos 1999 Pickering 2005 Sales 2007 Mayblin 2015) Asylum andimmigration are treated as one in the public imagination Increasingly restric-tive policies a focus on securing stronger and stronger border controls andthe ldquosecuritizationrdquo of migration closes down debate and increasingly pre-sents asylum seekers as ldquobogusrdquo ldquoillegalrdquo competing for ldquoourrdquo jobs andresources (Bauman 2004 Sales 2007 Jones et al 2014 Lewis et al 2014)

Marked by dynamics of inclusionexclusion for Lister (2007) citizenship is amulti-layered concept and involves an understanding of the individual as asocially situated self and not just a bearer of rights In resisting what is experi-enced as ldquoracialized practices of subjection and exclusionrdquo in their search forasylum the women expressed anxiety and concern at having to ldquosignrdquo at thepolice station every twoweeks This expectation andprocesswere experiencedas deeply problematic to all of the women They all spoke about the process asdifficult the ever-present risk of being detained the dehumanizing experienceand the sleepless nights that preceded their visit ldquoto signrdquo (Figure 3)

If you donrsquot sign in you can be taken to prison I signed today and all night I didnot sleep all night I feel sick I did not know what would happen to me Everyasylum seeker relates to the police station Most of us here have never beento police station in our home country so for me to go to police station Icould not believe it on top of everything else you are going through youhave to go to police station to sign For me because of my journalistic back-ground I was probing saying why why the police station just to put my signaturedown I go there and they say ldquoare you living at the same addressrdquo And you sayof course because you gave me the accommodation And we sign for oursupport It does not make sense I do not like to go there I really dislike it Butwe comply it does not make any sense I hate and dislike it but then I haveno choice (Sonja)

I hate this place it is the worst place in this town It is the police station Anyasylum seeker will not like this any time you go every 2 weeks I donrsquot sleep ifI go to sign this stress I have it is too much for me it is 5050 they maydetain you (Belle)

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 85

Seeking justice and recognition of their claims and building a sense ofbelonging the experience of signing at the police station defines women assubject-objects at the mercy of the state and the state officials and reducesthem to either having the right to remain [until the next time they sign] orto be detained and removed

One of the women was detained at the police station on the first day of ourwalks she was asked to return later that day and she was taken to a detentioncentre and subsequently removed from the UK The group immediatelysprang into action and organized a petition and worked with the RRFNE tooffer support and solidarity in seeking justice for her

The experience was a reminder of the fragile situations of the women in theldquomargins of the marginsrdquo and as Benhabib (2004 215) states the ldquosocial deathrdquoand ldquoquasi criminal statusrdquo afforded to those whose claims are refused whoare ldquoundocumentedrdquo and the subsequent curtailment of human civil and pol-itical rights of association and representation (Benhabib 2004 215)

Thatrsquos as far as it goes really we havenrsquot got much power being outside and wecanrsquot do much to be honest (Sonja)

The campaign petition and fundraising by the group members was anexample of resistance to ldquoracialized practices of subjection and exclusionrdquoand the right to citizenship and social justice

Many of the places and spaces we stopped at and discussed along the walkwere symbolic of the womenrsquos self-determination and agency in their search

Figure 3 Signing at the police station is part of the asylum process

86 M OrsquoNEILL

for asylum and freedom as well as the material spatial emotional and sym-bolic barriers they face and accommodate or overcome in the asylum process

Mo described the ldquorealities of the asylum systemrdquo in an image of ldquoa barriera wallrdquo She went on to share how ldquomany things are not allowed for us hellipdriving licence internet bank account hellip and universityrdquo Yet she alsodescribed feeling ldquoreally luckyrdquo because she is with her family that her sonis safe and she feels hopeful

The park green space and fountains were places that all of the women hadon their maps and were identified as positive places that make them feelgood Sonja shared her feelings about the fountains in the park and itsrelationship to their experience of the asylum process

We can see how the water comes up goes down and the pressure comes upagain It is symbolic for the women in the sense where they have beenpushed down by the system they fight they fight to stay up they fight andfight to come up again they fall but they get up again and rise

Importantly in the face of the women being rendered so isolated andpowerless the very act of sharing these experiences and making thempublic (to the researchersartists and through the film to a wider public) isone aspect of resistance and gaining political subjectivity against the back-drop of dehumanization humiliation and being deprived of dignity

The accommodation of women asylum seekers in Middlesbrough marksthem out both materially and symbolically because they were living inhouses with the doors painted red (Figure 4) This is currently the subject of

Figure 4 Red door

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 87

an inquiry by the Home Office The women described the stigmatizing effectbecause ldquoeveryone knows that asylum seekers live behind the red doorsrdquo Thismarked them out as Other as different as asylum seekers

After years of campaigning an award winning journalist from the TimesAndrew Norfolk took up the issue and printed a damning report thatnamed and shamed the housing provider JomastG4S and indeed local poli-ticians who had done nothing despite the campaigns that documented theracism and race hate that ensued ndash because of this symbolic and material sig-nifier They are currently being re-painted different colours (Norfolk 2016)

Other barriers defined by the women included the fact that public spacescan offer more protection than domestic spaces with officials entering thehomes of women without any notice reinforcing their lack of rights in thenew situation (Figure 5)

When you are an asylum seeker life is everywhere with the least facilities Wejust want to be alive

All of the women defined public spaces the community cafeacute open door (acharity that operated a foodbank and a drop in as well as support for the des-titute and undocumented) and the park university and library as places wherethey felt a sense of freedom community and belonging One womandescribed the greenspace in front of the library as her home

This is my home We are re building our life here I love the library I love it andmy children love it The library is celebrating 100 years I love to spend time here Ifeel so relaxed and I feel hospitality and welcome I sit in the park and feel free(Hanna)

Figure 5 Domestic spaces can be risky spaces

88 M OrsquoNEILL

This woman also ldquolovedrdquo living near the University and took many photo-graphs of the main building she had been a senior lecturer at a University inher home city Currently she is registering for her PhD at a University in theNorth East (Figure 6)

Teesside University is very close to my house I feel that I am living when I see theUniversity When I was 22 I studied for four years then I became an assistant lec-turer and then a lecturer and senior lecturer I feel like my life is the University(Hanna)

Recognition relationships and solidarity

The relational aspect of performing citizenship and belonging was high-lighted by all women Some of the women spoke about the importance ofa charity called Open Door in relation to both material and relationalsupport (Figure 7)

When I was thrown out of my accommodation the home office donrsquot care if youare a woman or a man they just throw you out and I wonder what people likeme can do without this place open door and when I come here they make feellike I belong like I am human

All of the women spoke about the importance of friendship and supportingeach other and the places and people that offer recognition support and soli-darity (Figure 8)

Figure 6 ldquoI feel I am living when I see the Universityrdquo

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 89

After a long time my first solicitor cut me off as they said I had only fifty per centcase Refugee Council were very good they supported me treated me normallynot as an asylum seekerhellip Lindarsquos Place Open Door and the Church help a lotWhen I did not sleep the whole night I go and I feel good there Linda helps a lotand makes you feel ok (Fran)

Figure 7 Sharing a walk

Figure 8 Friends and relationships are crucial for a sense of belonging offering supportand solidarity

90 M OrsquoNEILL

I am really lucky when I came here and meet new friends and heard about theirlife I realise that I am very lucky because I have a family I love my family andwhen we are together we are very happy because I have a son I have a verykind husband There are many problems for people who are single who livewith others and share kitchen and toilet and other things and it can be aproblem when they are alone (Mo)

The process of flight and arrival can be dangerous faced with barriers and feel-ings of displacement and loneliness Freedom safety hope friendship andbelonging are the building blocks of a new life

Organisations like Lindarsquos Place Open Door and the Church help a lot When Idid not sleep the whole night I go and I feel good there Linda helps a lot andmakes you feel ok supports is sympathetic and with all the negatives it is impor-tant that there are people like that

ldquoFreedom is the best thing in the whole world I need freedom more thanfood and oxygen We do not have freedom in my countryrdquo (Mo)

Taken together the themes emerging from the walks womenrsquos narrativesand the film created from the walks illustrate the ldquofour values of inclusive citi-zenshiprdquo that Kabeer (2005) defines as emerging from ldquoempirical work in theGlobal South and accounts from belowrdquo These four values are justice recog-nition self-determination and solidarity

Kabeer (2005 3) articulates these as follows justice involves ldquowhen it is fairfor people to be treated the same and when it is fair that they should betreated differentlyrdquo recognition involves ldquothe intrinsic worth of all humanbeings but also recognition of and respect for their differencesrdquo (4) self-deter-mination involves ldquopeoplersquos ability to exercise some degree of control overtheir livesrdquo (5) Solidarity is ldquothe capacity to identify with others and to actin unity with them in their claims for justice and recognitionrdquo (7) In discussingKabeerrsquos work Lister (2007 50ndash51) states that this ldquovalue could be said toreflect a horizontal view of citizenship which accords as much significanceto the relations between citizens as to the vertical relationship between thestate and the individualrdquo

In defining the development and momentum of the concept of citizenshipLister (2007 52) like Smith (1998) also highlights the work of Mouffe (1992)and Young (1990) specifically the benefit of an ldquoethos of pluralizationrdquo thatldquomakes possible a radical plural rather than a dual way of thinking about citi-zenship and identityrdquo Moreover in the process of working with group differ-ences ldquorather than suppressing themrdquo and where a radical plural ethos ispossible ldquowithout sacrificing citizenshiprsquos universalist emancipatory promiseis expressed in the ideals of inclusion participation and equal moral worthrdquo(Lister 2007 52)

Walking with women in Teesside underpinned by a participatory ethos ofinclusion participation valuing all voices has helped to make visible their per-forming and enacting citizenship in the context of complex social and

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 91

political locations (whilst also highlighting justice recognition self-determi-nation and solidarity)

To summarize the bottom line in relation to the womenrsquos accounts andenactments of citizenship is that through walking as a performative and bio-graphical method we were able to get in touch with lived experience in waysthat were creative relational discursive and reflective that both visualizedand performed justice recognition self-determination and solidarity Theresearch also highlighted the importance of innovate creative ways of con-sulting connecting with ldquounderstandingrdquo and sharing womenrsquos lives andstories

Arts-based biographical methods involve an organic approach to researchthat engages the performative and sensing body Arts-based walkingmethods are embodied relational sensory multi-modal and can often helpto access the unsayable or things that might not have emerged in a standardresearch interview They involve the role of the imaginary imagination andpolitics ndash a radical democratic imaginary The dialogue and understandingthat occurred as well as the visual outcomes helped to facilitate a space inwhich to articulate perform and build womenrsquos resources for citizenshipalbeit in contradictory and bounded ways The performative act of walkingby racialized migrant women in public spaces can be a radical act thatcreates space for critical thinking and discourse that challenges and worksagainst the grain that performs citizenship that ldquothe right to have rights isduerdquo (Isin and Nielsen 2008 2) From this perspective ldquodemocratisation isunderstood not as a set of superficial reforms but as the struggle to institutio-nalise a radical democratic pluralist imaginaryrdquo (Smith 1998 5)

The research analysis and outcomes utilized here provide us with anaccount of citizenship that counters exclusionary processes and practices gen-erates greater knowledge and understanding of womenrsquos resources in build-ing and performing cultural citizenship across racialized boundaries andseeks to deliver on social justice by facilitating a radical democratic imaginary

The task ahead is to sketch out the possibilities for a generative (radicaldemocratic imaginary) concept of transnational citizenship and communitythat transcends the limited and limiting notions of citizenship we find in gov-ernment responses to the asylum-migration and community nexus that con-nects the discursive reflective and relational aspects of social justice infurthering the creative performativities of citizenship from below Developingand extending creative arts-based walking biographical research withmigrant women as discussed in this paper is one way forward

Notes

1 The film was produced by Janice Haaken and Maggie OrsquoNeill [Accessed 21stJanuary 2017] httpswwwyoutubecomwatchv=SjT5lENga_M

92 M OrsquoNEILL

2 The author is a member of the Walking Artists Network and inspired by anumber of the walking women artists for example Claire Qualmann and DeeHedden of Walk Walk Walk

3 Social justice is defined by Hudson (2006) as discursive reflective andrecognitive

4 There was a common recognition that this is an urgent area of work in the NorthEast region as relatively little appeared to be known about the profile of Blackand Minority Ethnic (BME) groups including refugees and asylum seekers andthe criminal justice issues they face although anecdotal evidence suggestedboth that the BME population had grown significantly over the recent past(albeit from a level which was low relative to that in the UK as a whole) andthat the issue of racism was one which continued to affect them both in indi-vidual and institutional settings

5 The project and its methods are explainedmore fully in Haaken and OrsquoNeill 2014OrsquoNeill and Mansaray 2012 Haaken and OrsquoNeill 2014

6 Thanks to Misha Myers for this walking guidance see Myers 2006 OrsquoNeill andHubbard 2010

7 ldquoIt is to give oneself a general and genetic comprehension of who the person isbased on the (theoretical or practical) command of the social conditions of exist-ence and the social mechanisms which exert their effects on the whole ensem-ble of the category to which the person belongshellip and a command of thepsychological and social both associated with a particular position and a par-ticular trajectory in social spacerdquo (Bourdieu 1996 22ndash23)

8 Hudson (2006) writes that discursiveness relationalism and reflectiveness arethe ldquoprinciples that would characterize a justice that has the potential toescape being sexist and racistrdquo Moreover that ldquofeminist and race-criticalcriminologists have produced countless examples of the maleness and thewhiteness of criminal justicerdquo In part the evidence can be found in the relativedearth of research on womenrsquos experiences of gender biased asylum laws andpractices

Acknowledgements

With thanks to my co-researchers on this project ndash Susan Mansaray Jan Haaken andLucy Joy Jackson

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author

Funding

This work was supported by Leverhulme Trust [RF 2015 036 (R1764701)]

References

Adorno Theodor W 1978 Minima Moralia Reflections from a Damaged Life Translatedby E F N Jephcott London Verso

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 93

Agamben G 1995 Homo Sacer Sovereign Power and Bare Life Stanford CA StanfordUniversity Press

Anderson B 1991 Imagined Communities Reflections on the Growth and Spread ofNationalism London Verso

Arendt H 1998 The Human Condition Chicago IL University of Chicago PressBauman Z 2004 Wasted Lives Modernity and Its Outcasts Cambridge Polity PressBenhabib S 2004 The Rights of Others Aliens Residents and Citizens Cambridge

Cambridge University PressBourdieu P 1996 ldquoUnderstandingrdquo Theory Culture and Society 13 (2) 17ndash37Buscher M J Urry and K Witchger 2011 Mobile Methods London RoutledgeClark A and N Emmel 2010 Using Walking Interviews Manchester Morgan Centre

University of ManchesterCornell D 1995 The Imaginary Domain London RoutledgeCraig Gary Maggie OrsquoNeill Bankole Cole Georgios A Antonopoulos Carol Devanney

and Sue Adamson with Paul Biddle and Louise Wattis 2012 Race Crime and Justice inthe North East Durham University httpswwwduracukresourcessassresearchbriefingsResearchBriefing8-RacecrimeandjusticeintheNorthEastRegionpdf

De Certeau M 1984 The Practice of Everyday Life Translated by Steven RendallBerkeley University of California Press

Dolezal L 2015 ldquoThe Phenomenology of Self-presentation Describing the Structuresof Intercorporeality with Erving Goffmanrdquo Phenomenology and the CognitiveSciences 1ndash18 doi101007s11097-015-9447-6

Donovan Catherine Stephen MacDonald and John Clayton 2014 ldquoReporting andResponding to Hate Crime in the North East of Englandrdquo In Understanding HateCrime Research Policy and Practice University of Sussex Sussex May 8ndash9[Unpublished]

Edensor T 2010 ldquoWalking in Rhythms Place Regulation Style and the Flow ofExperiencerdquo Visual Studies 25 (1) 69ndash79

Erel U 2013 ldquoKurdish Migrant Mothers in London Enacting Citizenshiprdquo CitizenshipStudies 17 (8) 970ndash984 doi101080136210252013851146

Erel U A Reynolds and E Kapitani 2016 ldquoMigrant mothersrsquo creative interventions intoracialized citizenshiprdquo Ethnic and Racial Studies doi1010800141987020171317825

Fals Borda Orlando 1983 Knowledge and Peoplersquos Power Lessons with Peasants inNicaragua Mexico and Colombia New York New Horizons Press

Fals Borda O 1987 ldquoThe Application of Participatory Action-research in Latin AmericardquoInternational Sociology 2 329ndash347

Fraser N 2003 ldquoSocial Justice in the Age of Identity Politics Redistribution Recognitionand Participationrdquo In Redistribution and Recognition A Political PhilosophicalExchange edited by N Fraser and A Honneth 7ndash109 London Verso

Fulton H 2010 ldquoWalkrdquo Visual Studies 25 (1) 8ndash14Grossman A and A OrsquoBrien 2011 ldquolsquoVoicersquo Listening and Social Justice A

Multimediated Engagement with New Immigrant Communities and Publics inIrelandrdquo Crossings Journal of Migration and Culture 2 39ndash58

Haaken J and M OrsquoNeill 2014 ldquoMoving Images Psychoanalytically-informed VisualMethods in Documenting the Lives of Women Migrants and Asylum-seekersrdquoJournal of Health Psychology 19 (1) 79ndash89

Heddon S and C Turner 2010 ldquoWalkingWomen Interviews with Artists on the MoverdquoPerformance Research 15 (4) 14ndash22

Hudson B 2003 Justice in the Risk Society London Sage

94 M OrsquoNEILL

Hudson B 2006 ldquoBeyond White Manrsquos Justice Race Gender and Justice in LateModernityrdquo Theoretical Criminology 10 (1) 29ndash47 February

Ingold T and J Lee-Vergunst 2008 Ways of Walking Ethnography and Practice onFoot Aldershot Ashgate

Irving A 2010 ldquoDangerous Substances and Visible Evidence Tears Blood AlcoholPillsrdquo Visual Studies 25 (1) 24ndash35

Isin E F and G M Nielsen 2008 Acts of Citizenship 8 London Zed BooksJones H G Bhattacharyya K Forkert W Davies S Dhaliwal Y Gunaratnam E Jackson

R Saltus and Action Against Racism and Xenophobia 2014 ldquolsquoSwampedrsquo by Anti-Immigrant Communicationsrdquo Discover Society May 6

Jones E and J Gaventa 2002 Concepts of Citizenship A Review Brighton Institute ofDevelopment Studies

Kabeer N 2002 ldquoCitizenship and the Borders of the Acknowledged CommunityIdentity Affiliation and Exclusionrdquo IDS Working Paper 171 Brighton Institute ofDevelopment Studies

Kabeer N 2005 ldquoThe Search for Inclusive Citizenship Meanings and Expressions in anInterconnected Worldrdquo In Inclusive Citizenship 1ndash27 London Zed Books

Kaptani E and N Yuval-Davis 2008 ldquoParticipatory Theatre as a ResearchMethodologyrdquo Sociological Research Online 13 (5) 2 doi105153sro1789

Kindon S R Pain and M Kesby 2007 Participatory Action Research Approaches andMethods Connecting People Participation and Place London Routledge

Kispert M 2015 No More Beyond A Video Essay httpwwwmatthiaskispertcomvideono-more-beyond

Lewis H P Dwyer S Hodkinson and L Waite 2014 Precarious Lives Forced LabourExploitation and Asylum Bristol Policy Press

Lister R 2007 ldquoInclusive Citizenship Realizing the Potentialrdquo Citizenship Studies 11 (1)49ndash61 February

Lister Ruth Fiona Williams Anneli Anttonen Jet Bussemaker Ute Gerhard JacquelineHeinen Stina Johansson and Arnlaug Leira 2007 Gendering Citizenship in WesternEurope Bristol Policy Press

Littler M and M Feldman 2015 Tell MAMA Reporting 20142015 Annual MonitoringCumulative Extremism and Policy Implications Teesside University httptellmamaukorgtagteesside-university

Mayblin L 2015 ldquoWhy the UKrsquos 2015 Immigration Bill is Bad for Vulnerable MigrantWorkersrdquo Open Democracy December 7 httpswwwopendemocracynetbeyondslaverylucy-mayblinwhy-uk-s-2015-immigration-bill-is-bad-for-vulnerable-migrant-workers

Mouffe C 1992 ldquoFeminism Citizenship and Radical Democratic Politicsrdquo In FeministsTheorize the Political edited by J Butler and J W Scott 369ndash384 London Routledge

Myers M 2006 ldquoAlong the Way Situation-Responsive participation and educationrdquoThe International Journal of the Arts in Society 1 (2) 1ndash6

Myers M 2010 ldquoWalk with Me Talk with Me The Art of Conversive Wayfindingrdquo VisualStudies 26 (1) 50ndash68

Nagarajan C 2013 ldquoPoliticians and the Press are Locked in a Cycle of Increasing Anti-immigrant Rhetoric Presented as lsquoUncomfortable Truthrsquordquo Open DemocracySeptember 20

Nair P 2015 ldquoHome-work Gender and Urban Immigrant Relocationrdquo Open DemocracyJune 10 Accessed January 22 2017 httpswwwopendemocracynetwomenoftheworldhomework-gender-and-urban-immigrant-relocation

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 95

Norfolk A 2016 ldquoHome Office lsquoKnew Asylum Seekers Were Put in Houses with RedDoorsrsquordquo The Times January 27 httpwwwthetimescoukttopublicprofileAndrew-Norfolk

OrsquoNeill M 2010 Asylum Migration and Community Bristol Policy PressOrsquoNeill M 2011 ldquoParticipatory Methods and Critical Models Arts Migration and

Diasporardquo CrossingsMigration and Culture on lsquoThe Arts of Migrationrsquo 2 13ndash37OrsquoNeill M 2012a ldquoEthnomimesis and Participatory Artrdquo In Advances in Visual Methods

edited by S Pink 153ndash172 London SageOrsquoNeill M 2012b ldquoMaking Connections Art Affect and Emotional Agencyrdquo In Moving

Subjects Moving Objects Transnationalism Cultural Production and Emotions editedby M Svasek 178ndash201 Oxford Berghahn

OrsquoNeill M 2013 ldquoWomen Art Migration and Diaspora The Turn to Art in the SocialSciences and the lsquoNewrsquo Sociology of Artrdquo In Diasporic Futures edited by MarshaMeskimmon and Dorothy Rowe 44ndash66 Manchester University Press

OrsquoNeill M 2014 ldquoParticipatory Biographies Walking Sensing Belongingrdquo In Advancesin Biographical Research Creative Applications edited by M OrsquoNeill B Roberts andA Sparkes 73ndash89 London Routledge

OrsquoNeill M and P Hubbard 2010 ldquoWalking Sensing Belonging Ethno-mimesis asPerformative Praxisrdquo Visual Studies 25 (1) 46ndash58

OrsquoNeill M and S Mansaray 2012Womenrsquos Lives Well-being and Community Arts BasedBiographical Methods Durham University httpswwwduracukresourcessassresearchRaceCrimeandJusticeintheNorthEast-WomensLivesWell-beingExhibitionBookletpdf

OrsquoNeill M B Roberts and A Sparkes 2014 Advances in Biographical Methods co-editedwith Brian Roberts and Andrew Sparkes London Routledge

OrsquoNeill M and P Stenning 2014 ldquoWalking Biographies and Innovations in Visual andParticipatory Methods Community Politics and Resistance in Downtown East SideVancouverrdquo In The Medialization of AutoBiographies Different Forms and TheirCommunicative Contexts edited by C Heinz and G Hornung 215ndash246 HamburgUVK

OrsquoNeill M and J Perivolaris 2015 ldquoA Sense of Belonging Walking with Thaer ThroughMigration Memories and Spacerdquo Crossings Journal of Migration amp Culture 5 (2 amp 3)327ndash338

Osborne S 2016 ldquolsquoHundredsrsquo of Masked Men Beat Refugee Children in Stockholmrdquo TheIndependent January 30 httpwwwindependentcouknewsworldeuropehundreds-of-masked-men-beat-refugee-children-in-stockholm-a6843451html

Pakulski J 1977 ldquoCultural Citizenshiprdquo Citizenship Studies 1 73ndash86Pickering S 2005 Refugees amp State Crime Annandale The Federation PressPink S 2007 ldquoWalking with Videordquo Visual Studies 22 (3) 240ndash252Pink S 2008 ldquoMobilising Visual Ethnography Making Routes Making Place and

Making Images [27 paragraphs]rdquo Forum Qualitative SozialforschungForumQualitative Social Research 9 (3) Art 36 httpnbn-resolvingdeurnnbnde0114-fqs0803362

Pink S M OrsquoNeill A Radley and P Hubbard eds 2010 ldquoSpecial Edition of VisualStudiesrdquo Walking Ethnography And Art 25 (1) 1ndash7

Radley A K Chamberlain D Hodgetts O Stolte and S Groot 2010 ldquoFrom Means toOccasion Walking in the Life of Homeless Peoplerdquo Visual Studies 25 (1) 36ndash45

Reason P and H Bradbury 2008 The SAGE Handbook of Action Research ParticipativeInquiry and Practice New York Sage

96 M OrsquoNEILL

Reynolds T and U Erel 2016 ldquoMigrant Mothers Creative Interventions intoCitizenshiprdquo Open Democracy January 22 httpswwwopendemocracynettracey-reynolds-umut-erelmigrant-mothers-creative-interventions-into-citizenship

Roy Alastair Neil Jenny Hughes Lynn Froggett and Jennifer Christensen 2015 ldquoUsingMobile Methods to Explore the Lives of Marginalised Young Men in Manchesterrdquo InInnovations in Social Work Research edited by Louise Hardwick Roger Smith andAidan Worsley 153ndash170 London Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Sales R 2007 Understanding Immigration and Refugee Policy Contradictions andContinuities Bristol Policy Press

Scheff T 2006 Silence and Mobilization Emotionalrelational Dynamics AccessedOctober 18 2015 httpwwwhumiliationstudiesorgdocumentsScheffSilenceandMobilizationpdf

Schuster L and J Solomos 1999 ldquoThe Politics of Refugee and Asylum Policies inBritain Historical Patterns and Contemporary Realitiesrdquo In Refugees Citizenshipand Social Policy in Europe edited by A Bloch and C Levy Basingstoke Macmillan

Schuster L and J Solomos 2004 ldquoRace Immigration and Asylum New LabourrsquosAgenda and Its Consequencesrdquo Ethnicities 4 (2) 267ndash300

Smith A M 1998 Laclau and Mouffe The Radical Democratic Imaginary LondonRoutledge

Solnit R 2001 Wanderlust A History of Walking London VersoSmith R J and T Hall 2016 ldquoPedestrian Circulations Urban Ethnography the

Mobilities Paradigm and Outreach Workrdquo Mobilities 11 (4) 497ndash507 doi1010801745010120161211819

Sommers J 2016 ldquoDover Protest Turns Violent as Far Right Clashes with Anti-FascistDemonstratorsrdquo The Huffington Post January 30 httpwwwhuffingtonpostcouk20160130dover-protest-turns-violent-demonstrator-bloodied_n_9119604html

Tastoglou E and A Dobrowlesky eds 2006Women Migration and Citizenship MakingLocal National and Transnational Connections Aldershot Ashgate

Urry J 2007 Mobilities Cambridge PolityYoung Iris Marion 1990 Justice and the Politics of Difference Princeton NJ Princeton

University PressYuval-Davis N 2006 ldquoBelonging and the Politics of Belongingrdquo Patterns of Prejudice 40

(3) 197ndash214

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 97

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Socio-cultural-political context

-

- ldquoWomen well-being and community in Teessiderdquo

-

- Walking methods why walking

- Performing cultural citizenship

-

- Womenrsquos storytelling capacities

- Self-determination and agency othering and resisting ldquoracialized practices of subjection and exclusionrdquo in seeking citizenship

- Recognition relationships and solidarity

-

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Disclosure statement

- References

-

Walking well-being and community racializedmothers building cultural citizenship usingparticipatory arts and participatory action researchMaggie OrsquoNeill

Department of Sociology The University of York York UK

ABSTRACTCommitted to exploring democratic ways of doing research with racializedmigrant women and taking up the theme of ldquowhat citizenship studies canlearn from taking seriously migrant mothersrsquo experiencesrdquo for theory andpractice this paper explores walking as a method for doing participatory arts-based research with women seeking asylum drawing upon researchundertaken in the North East of England with ten women seeking asylumTogether we developed a participatory arts and participatory action researchproject that focused upon walking well-being and community This papershares some of the images and narratives created by women participantsalong the walk which offer multi-sensory dialogic and visual routes tounderstanding and suggests that arts-based methodologies using walkingbiographies might counter exclusionary processes and practices generategreater knowledge and understanding of womenrsquos resources in building andperforming cultural citizenship across racialized boundaries and deliver onsocial justice by facilitating a radical democratic imaginary

ARTICLE HISTORY Received 26 February 2016 Accepted 13 March 2017

KEYWORDS Walking mobile methods cultural citizenship racialized mothers participatory actionresearch social justice

Introduction

In the introduction to this special issue Erel Reynolds and Kaptani (2016)explore ldquothe everyday experiences of participation and belonging ofmigrant mothers in actively forming new understandings of community citi-zenship and political subjectivity against the grain of racialized practices ofsubjection and exclusionrdquo This paper contributes to this project by exploringwalking as a method of conducting research with migrant women drawingupon participatory research conducted with ten women in the North Eastof England some of whom are mothers and at the time of the researchwas either seeking asylum had refugee status [one woman] or were

copy 2017 Informa UK Limited trading as Taylor amp Francis Group

CONTACT Maggie OrsquoNeill MaggieoneillYorkacuk

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 2018VOL 41 NO 1 73ndash97httpsdoiorg1010800141987020171313439

undocumentedhad no recourse to public funds [their claim for asylum hadbeen refused]

The research used participatory arts (PA) and performative methods includ-ing walking photography and film Outcomes included a series of walks anexhibition a film1 and some co-produced articles These outcomes are uti-lized in this paper to explore the ways in which the women ldquowho are not citi-zens participate in the common social economic and political life of a specificstate and claim rights in these multiple domainsrdquo (Isin and Nielsen 2008) Theresearch is underpinned by the interrelationship between critical theory livedexperience and ldquopraxisrdquo (as purposeful knowledge) in documenting andunderstanding womenrsquos lives experiences and their senses of ldquobelongingrdquoas a dynamic process (Yuval-Davis 2006 OrsquoNeill 2010 Haaken and OrsquoNeill2014)

In walking with the women through a series of collective walks post walkworkshops and discussions knowledge and ldquounderstandingrdquo (Bourdieu 1996)is gained of womenrsquos experiences in space time and place (Heddon andTurner 2010) as well as their inter-subjective inter-corporeality (Dolezal2015) their struggle for recognition belonging as well as their ldquoenactmentsrdquoof cultural citizenship in the new situation By cultural citizenship (Pakulski1997) I mean the right to presence and visibility not marginalization theright to dignity and maintenance of lifestyle ndash not assimilation to the domi-nant culture and the right to dignifying representation ndash not stigmatization

This research builds upon the authorrsquos long history of doing PA and parti-cipatory action research (PAR) with groups and communities artists and com-munity arts organizations (OrsquoNeill 2010) and her use of walking as an arts-based practice and biographicalnarrative method (OrsquoNeill and Hubbard2010 Pink et al 2010 OrsquoNeill and Stenning 2014 OrsquoNeill and Perivolaris2015) The research contributes to the rich literature on PAR (Fals Borda1983 1987 Kindon Pain and Kesby 2007 Reason and Bradbury 2008) andracialized citizenship (Kabeer 2002 Erel Reynolds and Kaptani 2016) It alsocontribute to the developing field of mobilities research (Urry 2007Buscher Urry and Witchger 2011 Roy et al 2015 Smith and Hall 2016)However the use of walking as a biographical and phenomenologicalmethod2 was inspired by artists (as well as social scientists) as a way ofdoing arts-based biographical research The research was also influenced byfeminist and critical theoretical work on contested citizenship (Kabeer 2005Lister 2007 Lister et al 2007) social justice3 (Hudson 2006) the importanceof the imaginary domain (Cornell 1995) and the concept of a radical demo-cratic imaginary (Smith 1998)

In seeking to make sense of the migrant womenrsquos experiences bothpsychic and socialmaterial in performing and enacting citizenship thispaper claims that walking as an arts-based biographical research methodoffers a powerful route to understanding the lived experiences of women

74 M OrsquoNEILL

as well as the development of processes and practices of inclusion towards aradical democratic imaginary Indeed for the women participants walking inMiddlesbrough is a radical democratic act and performance For Cornell (1995)like Smith (1998) the imaginary domain is a moral and psychic space that isnecessary in order to open keep open and rework the repressed elementsof the social imaginary

Centrally the paper reflects upon how asylum seeking and undocumen-ted women creatively enact and perform citizenship through their everydaymobilities their attachments to place and space in Teesside and their situa-tional authority in guiding the collective walks At the same time it evi-dences how women contest or challenge hegemonic and racializedldquopractices of subjection and exclusionrdquo (Erel Reynolds and Kaptani 2016see also Kaptani and Yuval-Davis 2008) in both their experiences of livingin Teesside as well through their contributions and participation to thearts-based project

Committed to exploring democratic ways of doing research with migrantwomen and taking up the concept of women migrants ldquoenacting citizenshiprdquo(Erel 2013 Nair 2015) this paper shares the PA-based research conducted withten women seeking asylum in the North East of England and extends debateson visual walking and mobile methods cultural citizenship racialized citizen-ship belonging community and social justice for women seeking asylum inthe UK

Socio-cultural-political context

Women seek asylum for the same reasons as men as well as fleeing gender-based sexual violence Yet these gendered dynamics are an under examinedtopic (Nair 2015) The recent Immigration Act 2016 alongside a range ofrestrictions put into place mean that it is incredibly hard to gain refugeestatus in Britain if you do it is temporary and this increases vulnerabilityespecially for families (Mayblin 2015) Moreover the cultural and material land-scape of ldquoBrexitrdquo in the UK makes for a hostile climate for both new arrivalsand longer term migrants waiting for decisions on their asylum and immigra-tion claims

Recent migration surge in Europe Europeanization of restrictive asylumpolicy geopolitical changes what Bauman (2004) calls ldquonegative globalisa-tionrdquo EU enlargement ldquoBrexitrdquo and ldquoIslamophobiardquo have heightened secur-ity concerns about unregulated migration and porous borders In the UK aldquorace relations frameworkrdquo (Schuster and Solomos 2004) is central to thedevelopment of asylum policy and most people come to understand thelived experience of asylum exile and processes of belonging in contempor-ary western society through the mediated images and narratives of themass media

ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 75

What is clear is that refugees and asylum seekers have become the folkdevils of the twenty-first century and overall mainstream media represen-tation of the asylum issue the scapegoating of asylum seekers and tabloidheadlines help to create fear and anxiety about the unwelcome ldquoothersrdquoand to help set agendas that fuel racist discourses and practices As Nagarajan(2013) argues ldquopoliticians and the press are locked in a cycle of increasing anti-immigrant rhetoric presented as lsquouncomfortable truthrsquo Yet the problem is notimmigration but socio-economic inequalityrdquo

Moreover Reynolds and Erel (2016) identified how migrant mothers aredemonized as ldquobenefit cheatsrdquo ldquohealth touristsrdquo and ldquowelfare scroungersrdquoThe ldquocultural diversity they embody rather than being celebrated is similarlyviewed in terms of constituting a potential threat to social and cultural cohe-sionrdquo despite the fact that they make a significant contribution to UK societyand ldquotheir cultural diversity can contribute to developing a future citizenrymore comfortable with culturally and ethnically plural identitiesrdquo

The broader conflict at the centre of western nationsrsquo responses to theplights of asylum seekers and refugees is seen in the changing responseto migration surge in the Mediterranean alongside a commitment toHuman Rights and the 1951 Convention in the UK and on the other handpowerful rhetoric aimed at protecting the borders of nation states under-pinned by the message ldquoGo Homerdquo or ldquostay outrdquo as states lock down theirborders and more recently in the mobs attacks on refugees in Stockholm(Osborne 2016) and the English Defence League marches in Dover(Sommers 2016)

The movement of people across borders is a key defining feature of thetwentieth and twenty-first centuries In Matthias Kispertrsquos film No MoreBeyond (2015) one of his interviewees who had walked to the Melilla crossingfence asks ldquoWhat is the legal way to immigrate Why donrsquot they give me thisoption I am illegal because there is no legal routerdquo

Arendt (1998) identified ldquothe twin phenomena of lsquopolitical evilrsquo and lsquostate-lessnessrsquo as the most daunting problems of the twentieth and twenty-firstcenturyrdquo (Benhabib 2004 50) Statelessness for Arendt meant loss of citizen-ship and loss of rights indeed the loss of citizenship meant the loss ofrights altogether ldquoOnersquos status as a rights-bearing person is contingentupon the recognition of onersquos membershiprdquo and ldquoIn Arendtian language theright of humanity entitles us to become a member of civil society such thatwe can then be entitled to juridico-civil rightsrdquo (Benhabib 2004 59)

Benhabib (2004) acknowledges the bifurcation between on the one handuniversal human rights and on the other the right of state protection andthat the nation state system carried ldquowithin it the seeds of exclusionaryjustice at home and aggression abroadrdquo (61) Thus the conflict between univer-sal human rights and sovereignty claims are ldquothe root paradox at the heart ofthe territorially bounded state-centric international orderrdquo (Benhabib 2004 69)

76 M OrsquoNEILL

This is documented very clearly in the work of Tastoglou and Dobrowlesky(2006) who discuss the ldquoglobal realities that stem from the intricate interplayof gender migration and citizenship and the inclusions and exclusions thatresult under specific conditionsrdquo (Tastoglou and Dobrowlesky 2006 4) Fordespite the right to seek asylum being a human right as both Benhabib(2004 69) and the current responses to migration surge across Europe illus-trate ldquothe obligation to grant asylum continues to be jealously guarded bystates as a sovereign principlerdquo Not having onersquos papers in order being undo-cumented sans papiers is a form of social death that brings with it ldquoquasi crim-inal statusrdquo a curtailment of human rights and no civil and political rights ofassociation and representation (Benhabib 2004 215)

For Benhabib ldquothe extension of full human rights to these individuals andthe decriminalisation of their status is one of the most important tasks of cos-mopolitan justice in our worldrdquo (2004 168) Concepts of what constitutes citi-zenship and also social justice is vital in addressing these issues andinequalities and can be explored through processes and practices of exclu-sion and inclusion

It is within this precarious social political and cultural context that asylumseeking women perform acts of cultural citizenship that are not just aboutrights and obligations but about negotiating belonging and as Lister et al(2007 9) drawing upon Fraser (2003) states ldquoan important element of belong-ing is participationrdquo Moreover for Lister et al (2007 10) citizenship is experi-enced across a number of levels ldquofrom the intimate through the local nationaland regional to the global where it is sometimes represented in the languageof cosmopolitanism and of human rightsrdquo Referencing Jones and Gaventa(2002) Lister et al (2007) describe how such multi-layered understandingsof citizenship need also to be concerned with the ldquoconcrete lsquospaces andplacesrsquo in which citizenship is practicedrdquo as an ldquoidentity and practicerdquo

ldquoWomen well-being and community in Teessiderdquo