Voyage of Freedom, Voyage of Doom transatlantic liner St. Louis 1939

-

Upload

moulin-kubis -

Category

Documents

-

view

119 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Voyage of Freedom, Voyage of Doom transatlantic liner St. Louis 1939

-

Jewish refugees trapped between U.S. immigration laws

and duplicitous Cuban ofcials face a return to Nazi Germany

by Barbara D. Krasner

-

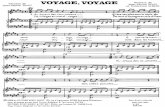

The refugee ship St. Louis sets sail

from Hamburg, Germany, on May 13,

1939, with 937 Jewish refugees bound

for Cuba. A ship-to-shore radiogram

in German (inset) was sent by Moritz

Schoenberger to family on Long Island,

N.Y., on May 25. Schoenberger reported

he was physically and spiritually

recovered from his trek and was most

confdent about reaching Havana.

The message is signed Kisses, papa.

Two days later the ship was denied

entry to Cuba and was forced to return

to Europe, where Schoenberger

was interned in occupied France; he

eventually made it to the United States

and became an American citizen in 1946.

BoTh images: uniTeD sTaTes holocausT memorial museum

AUGUST 2014 55

-

56 AMERICAN HISTORY

Hull merely replied, Yes.

Morgenthau, himself of German-Jewish descent, continued.

And there have been so many things back and forth as to what

could or couldnt be done.

He then suggested possible courses of action to help the

refugees. But in the end, Hull said, Well, thisyou see, this is

a matter primarily between Cubaand these peopleand not

between this Government.

Since Adolf Hitlers rise to power as chancellor of Germany

in 1933, Jews had been the target of restrictions, boycotts and

attacks. In 1935 he stripped them of their citizenship. By 1938

it became clear that Germany was no place for Jews. In July,

representatives from 32 countries attended a conference in

Evian, France, called by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

to discuss the plight of Germanys Jews. Holland and Denmark

ofered temporary asylum to a few refugees. Te Dominican

Republic ofered to take 100,000 Jews. No one else spoke up,

just as Hitler expected, not even the United States, which re-

fused to alter the strict quotas that limited immigration to the

country. Ten Hitler ratcheted up the pressure. On November

9-10, 1938, his Brown Shirts enacted the orgy of terror called

KristallnachtNight of Broken Glass. Tey desecrated and

burned more than 1,000 synagogues, vandalized tens of thou-

sands of Jewish shops and arrested a quarter of the Jewish male

population, taking them to the concentration camps at Buch-

enwald, Sachsenhausen and Dachau.

Lawyer Josef Joseph from Rheydt in western Germany was

one of those arrested, but because he was well known in his

town, authorities detained him in the local jail. Once back

home and stripped of his law practice, Joseph moved to get

his wife and 10-year-old daughter, Liesl, out of Germany. He

applied for a visa to the United States, where immigrants with

close relatives were given preferred status. His wifes family in

Philadelphia provided an afdavit of sponsorship, but the visa

number was high. A friend in Cuba ofered to sponsor the Jo-

sephs until their number was called. Ten Joseph saw the ad

for the St. Louis luxury liner bound for Cuba. He called the

Hamburg-Amerika shipping line to make a frst-class reserva-

tion for his family and procured the special landing permits

required by the Cuban immigration ofce.

On the morning of November 10, 1938, 10-year-old Hans

Fisher got up for school as usual and lef his apartment build-

ing in Breslau in eastern Germany. I noticed mounds of bro-

ken glass on the sidewalk, he remembered later. I suddenly

saw before me a large crowd, including some of my school

mates, stopped by a police wooden barricade. Before I even

had a chance to talk to anyone, a cry went up from the crowd,

Look, look, the synagogue is on fre! Hans ran home to tell

his parents. Within a few minutes, two Gestapo agents were at

the door. Tey ordered Hans father to pack a small bag with

socks and underwear. He was taken to Buchenwald.

Because Mr. Fisher had been decorated with the Iron Cross

for his military service to Germany in World War I, he had an

entry visa to Panama. (Holders of the Iron Cross or other med-

als sometimes received such special dispensation.) Fisher was

released from Buchenwald in January 1939 on the condition

that he leave Germany within two weeks. He complied but fa-

vored Cuba over Panama, so he secured a visa and settled in

Havana in early February. Te family prepared to meet him

there, but Hans contracted scarlet fever and the trip was delayed

for nearly two months. Finally, Hans mother bought passage to

Cuba on the St. Louis for herself, Hans and his older sister.

Herbert Karliner, 13, and his familyparents Josef and

Martha, and siblings Ilse, 16, Walter, 14, and Ruth, 12trav-

eled from Peiskretscham in eastern Germany to board the St.

Louis in Hamburg. Josef had spent three weeks in Buchenwald

afer his arrest during Kristallnacht, and Martha bought him a

visa for Shanghai. But he did not want to go to China alone,

and eventually they found that the entire family could enter

Cuba, where Marthas brother lived and worked as a lawyer.

Fritz Buf, 17, traveled alone. He was attending a trade

school in Munich, away from his parents and sister in another

part of Bavaria. His family, whose ancestors had lived in Ba-

varia since the early 1600s, had already registered with the U.S.

consulate for their visas. Te plan was for Fritz to leave frst

and the rest of the family would soon follow. He noted in his

On the afernoon of June 5, 1939, Sec-

retary of the Treasury Henry Mor-

genthau Jr. placed a call to Secretary

of State Cordell Hull. Cordell, some

of my good friends in New York have

called me up about this terrible tragedy

on this boat the St. Louis with those 900 refugees on it. Mor-

genthau was referring to German-Jewish refugees bound for

Cuba who were denied landing in Havana harbor.

europe cannot settle down until the Jewish question is cleared up,

said Adolf Hitler in 1939 in what is now known as the prophecy speech.

-

AUGUST 2014 57AbOvE: GERMAN pHOTOGRApHER (20TH CENTURY)/ S2 pHOTO/THE bRIdGEMAN ART lIbRARY; RIGHT: Ap; OppOSITE: EvERETT COllECTION HISTORICAl/AlAMY

diary, It is with mixed feelings that we aboard take our own

personal farewell from Germany by trying to sever all memo-

ries of our lives to date. . . . With tears in our eyes we could not

completely forget what we called our home, our place of birth.

He and others clung to the telephone at the pier to say their last

goodbyes to family and friends.

Captain Gustav Schroeder, his crew and the 937

passengers on the St. Louis lef Hamburg on May

13, 1939, unaware that on May 5, the Cuban gov-

ernment had enacted Decree 937 rendering the

landing permits worthless. New arrivals had to

have written permission from the Cuban secretary of state

and secretary of labor and post a $500 bond. (American tour-

ists, however, were exempt from the bond.) Although both

Hamburg-Amerika and the American Jewish Joint Distribu-

tion Committee (JDC, a relief organization that helped Jews

worldwide) received warning, neither alerted the St. Louis that

the refugees would be refused admission.

Captain Schroeder learned the truth during the voyage. He

formed a passenger committee and asked Josef Joseph to serve

as its chairman. On May 23, a committee member asked, Are

we here to prepare for returning to Germany?

At this stage, the answer is no, Schroeder replied. We will

sail to Havana. But I cannot say what will happen when we

reach there.

Despite the uncertainty, the passengers enjoyed their cruise.

Said Hans Fisher, We really felt free, even though it was still

a German boat. Schroeder agreed to passenger requests to

cover or remove the portraits of Hitler displayed in the public

rooms. Afer two weeks at sea, the ship prepared for its fnal

approach to Havana. Passengers reported to the pursers ofce

to collect their landing cards for disembarkation. Tey packed

and placed their luggage outside their cabin doors.

Te St. Louis pulled into Havanas harbor in the predawn

hours of Saturday, May 27. A trumpet played Freut Euch des

LebensBe Joyful About Life. Fritz Buf wrote, We came

aboard this ship in Hamburg as individuals with a common

destiny, and we will leave this ship like a community that has

had the good fortune to travel together. But he wondered,

When can we ever again experience such joyful days?

Joseph brought Liesl on deck. It was like a paradise, she

remembered later. Tere were palm trees and pastel-colored

houses and fowers. Te day that we were supposed to get of,

the luggage had been brought up, there was a lot of excitement

and activity going on. A few people had gotten of already

when everything stopped. Everybody got a little bit upset and

they asked the shore patrol that had come aboard what was

going on. When can we get of? And the answer was always

Maana, with a smile.

Twenty-two passengers with the required documentation

were allowed to disembark. Fify members of the Cuban police

patrolled the decks and secured the gangways. Hans Fishers

father was waiting for him: Little rowboats appeared that

circled the ship, and my father was on one of them, but you

could barely see one another, you couldnt speak. First of all

there was so much noise because there were so many, but also

we were so high up, you couldnt talk.

an anti-semitic poster linking Jews and communism was placed on

the window of a Jewish-owned shop in San Francisco in 1938, the year a

Gallup poll found that half of all Americans had a low opinion of Jews.

roosevelt and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau on the eve of

the 1940 election. Critics charged FDR with showing undue deference

to Jewish advisers and vilifed the New Deal as the Jew Deal.

-

58 AMERICAN HISTORY

in retaliation for the murder

of a German embassy ofcial

in Paris by a 17-year-old Polish

Jew, Jewish communities

throughout Germany were

violently attacked in November

1938. Propaganda minister

Joseph Goebbels announced

that, in response to the murder,

the Nazi Party would hold

no ofcial demonstrations

but insofar as they erupt

spontaneously, they are not

to be hampered. Thousands

of synagogues and Jewish

businesses were destroyed, 91

Jews were killed and 30,000

Jewish men were arrested.

Among the scenes in Berlin

(clockwise from top): a smashed

storefront in the Judengasse

(Jews Alley); cleanup at the

Jewish-owned Kaliski Bedding

Establishment; and the burned-

out Fasanenstrasse Synagogue,

the remains of which were

destroyed in an Allied bombing

raid in 1943.

Kristallnacht: Night of Broken Glass

-

AUGUST 2014 59OppOSITE, ClOCkwISE fROM TOp: RUE dE ARCHIvES/THE GRANGER COllECTION, NEw YORk; HUlTON-dEUTSCH COllECTION/CORbIS; Ap

Negotiation was the only hope for the passengers of the St.

Louis, and responsibility for it fell to New York City lawyer Law-

rence Berenson, representing the JDC. President of the Cuban

Chamber of Commerce, a personal friend of Cubas powerful

military leader Fulgencio Batista and counsel to the Republic

of Cuba, Berenson had credentials and connections. He arrived

by seaplane on May 30, but he cautioned the JDC: It will take

money more than anything else to buy them their freedom.

On board the St. Louis, some of the refugees were getting

desperate. Max Loewe locked himself into the mens room on

A Deck and slit his wrists. Ten he jumped overboard. Te

ship sounded a long blast and crew members raced along

the deck. One sailor dove into the water and grabbed hold of

Loewe, who resisted, shouting, Let me die, let me die! But he

was pulled to safety. His family was not allowed to accompany

him to a Havana hospital, where he again attempted suicide.

(Loewe survived and was later reunited with his family.) Cap-

tain Schroeder formed a suicide watch of 15 men to patrol the

decks in two-hour shifs.

Te hulking ship became a tourist attraction as photog-

raphers and newsreel flm crews aimed their cameras at the

passengers. In New York, relatives and friends raced to Times

Square to pick up the latest newspaper reports. Demonstra-

tions broke out in Atlantic City, New York, Chicago and Wash-

ington. Concerned American Jews sent messages to President

Roosevelt, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickeswho had

proposed a plan to settle Jewish refugees in AlaskaRoman

Catholic cardinals and Supreme Court justices, urging them

to do whatever they could to get Cuban president Federico

Laredo Br to repeal Decree 937. On board, the radio ofcer

tapped out innumerable messages pleading for help. Female

passengers pressed for support from the Cuban presidents

wife. Mrs. Br did not respond. Children wrote to frst lady

Eleanor Roosevelt. She did not respond.

Meanwhile, Berenson received word from Batista that he

had arranged an appointment with Br for Tursday, June

1. At the presidents palace, Berenson made his plea to allow

the refugees of the ship, but he didnt get the reaction he ex-

pected. Instead, Br barked that the St. Louis had to leave Ha-

vana: Te ship must go out. I wont permit it to remain in the

harbor. I will talk to you afer that is done. Berenson pleaded

once more. Br said, Tree miles is all that is necessary and

the minute it is out come back with the plan and I will be ready

to go over it with you. Berenson had no choice but to comply

with the presidents demands, and Captain Schroeder received

a written order to take his ship into international waters im-

mediately. He was only able to negotiate another 24 hours to

take on food and supplies.

Liesl Joseph recalled, When the day of departure came

[June 2], it probably was one of the darkest days in the lives of

everybody, and the shore patrol followed the ship to make sure

nobody jumped overboard, but in the meantime they were

shouting us farewell and communications would go on. Most

likely youll be back here in a few days and everything will be

OK. But it didnt happen.

Josef Joseph wrote in his diary, From here on in, what had

started as a voyage to freedom became a voyage of doom.

The Cuban government stipulated payment of $500

per personalmost half a million dollars total

to ensure that the refugees would not become

public charges. Te JDC authorized Berenson to

ofer $125,000 for all the refugees, and increased

that fgure over the next several days. Te U.S. State Depart-

ment believed the Cubans were blufng and advised Berenson

not to put up the money, but Berenson and the JDC forged

ahead. Teir plan now included landing at the Isle of Pines,

a small island of the Cuban coast that Br mentioned as a

possible disembarkation site. Berenson reviewed the proposal

with high-ranking Cuban ofcials and expected everything to

proceed smoothly in his next meeting.

While the negotiations were under way, Schroeder ordered

the St. Louis to cross between Cuba and Florida. Passengers

sighted Miamis palm trees and beaches along with U.S. Coast

Guard cutters, which were under the jurisdiction of Treasury

Secretary Morgenthau. Te New York Times reported the

Coast Guard was instructed to trail the ship, and a patrol boat

accompanied the liner to prevent attempts by passengers to

jump overboard and swim to American shores. Secretly, Mor-

genthau, a JDC supporter, had arranged for the Coast Guard

to confdentially keep him apprised of the ships location. Te

passengers knew none of this, however, and Captain Schroed-

er wrote in his diary, To me, it was as if the world had thrown

away the entire St. Louis.

DespiTe the growing crisis for

European Jews, Americans in the

late 1930s were reluctant to ease the

most restrictive immigration policy in

the nations history. Immigration was

limited to 150,000 entrants a year,

with strict quotas based on the country

of origin. In 1939, the year the St.

Louis was forced to return to Europe,

Congress rejected a bill to waive the

quotas and allow 20,000 Jewish

children under the age of 14 to seek

refuge in the United States. between

1933 and 1945, fewer than 200,000

Jews were admitted. In January 1944,

Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau

charged the State department with

the wilful [sic] failure to act and

wilful attempts to prevent action

from being taken to rescue Jews

from Hitler. In response, president

franklin Roosevelt established the war

Refugee board and ordered the State,

Treasury and war departments to

coordinate their eforts to rescue the

victims of enemy oppression who are

in imminent danger of death. by the

end of the war in 1945, the board had

assisted some 200,000 Jewish and

other war refugees.

u.s. stands firm on quotas

-

clockwise from top right: A refugee waves a tearful

goodbye as the St. Louis is forced to leave Havana.

Oskar, Salo, Jakob and Leo Blechner pose for a happy

family photo before Oskar sails for Cuba. Oskar survived

the war in England; Leo made it to the U.S.; Jakob went to

Switzerland. Salo survived Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz and

Bergen-Belsen. Their parents both died in the camps.

Rudi Dingfelder (far right) and his parents, Leopold

and Johanna, aboard ship. The family ended up in the

Netherlands before the Nazi occupation. Rudis parents

died at Auschwitz; Rudi survived several camps and a

forced march. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1947.

Ruth Karliner and her brother Herbert sailed on the St.

Louis with the rest of their family. They found refuge in

France after their return to Europe. Herbert survived the

war and came to the U.S. in 1946; Ruth died at Auschwitz.

Forgetting Is Not an Option

-

AUGUST 2014 61AbOvE: U.S. HOlOCAUST MEMORIAl MUSEUM, COURTESY Of HERbERT & vERA kARlINER; OppOSITE, TOp RIGHT: GAMMA-kEYSTONE vIA GETTY IMAGES; All OTHER IMAGES U.S. HOlOCAUST MEMORIAl MUSEUM, TOp lEfT: COURTESY Of HERbERT & vERA kARlINER, bOTTOM lEfT: COURTESY Of GERRI fEldER, bOTTOM RIGHT: COURTESY Of blECHNER fAMIlY (lONdON, zURICH, bOSTON)

On June 2, the day the ship lef Havana, Berenson inspected

the Isle of Pines and also received a visit from the consul of the

Dominican Republic, who ofered the refugees asylum at $500

per person, although the amount appeared to be negotiable.

But Berenson kept his hopes pinned on Cuba, and three days

later a breakthrough seemed imminent. A Miami radio station

broadcast the news that Br had granted permission for the St.

Louis to land at the Isle of Pines. Te ships radio room picked

up the message, and the St. Louis turned toward Cuba.

Te next morning, however, the radio room received another

cable: Isle of Pines not confrmed. Br had issued a shocking

statement: Yesterday Seor Berenson made an alternative pro-

posal ofering $443,000 [$500 per person excluding children

under 16] for the St. Louis passengers. . . . Te Cuban govern-

ment could not accept the proposal, and having passed exces-

sively the time allowed, the government terminates the matter.

Te JDC was taken by surprise and believed Berenson had

been misled deliberately so as to prevent an acceptance in

precise terms of the ofer that the President had made. In an-

nouncing that a deadline had passed, Br would appear to have

done all he could. Still, the organization deposited the money

Br wanted with the Chase Bank. But

Br refused to negotiate further.

Shortly before midnight, June 6,

Schroe der received instructions to re-

turn to Hamburg immediately. Pan-

icked passengers confded in him:

Teyd prefer the North Sea over the

KZ (Konzentrationslager, or concen-

tration camp), which will be our end.

Te captain hatched a plan to scuttle

the ship of the coast of Britain.

In New York, the JDC cabled the

heads of major relief organizations,

leaving no stone unturned in attempt-

ing to aid the St. Louis passengers. But

the Dominican Republic ofer came

to nothing. Colombia, Argentina and

Chile declined to assist. Venezuela, Ec-

uador and Paraguay did not respond.

Te JDC began to explore options in

Europe, including Belgium, Holland, Luxemburg and Portugal.

Te committees European chairman, Morris Troper, worked

the phones and fred of telegrams day and night from his Paris

ofce. Of the 937 passengers, 743 had afdavits and visas for

the United States that would admit them from within six

months to two years. By June 10, Troper learned Belgium would

accept 250 of those passengers, Great Britain another 250.

Troper worked against the clock. Finally on June 12, he

cabled Josef Joseph on board ship: Final arrangements for

disembarkation all passengers completed stop Happy inform

you governments of Belgium Holland France and England

cooperated magnifcently with American Joint Distribution

Committee to efect this possibility.

Fritz Buf wrote, Our jubilation was fantastic, indescrib-

able, and spontaneous. Te horizons have opened up. We were

not forgotten afer fve weeks at sea.

When the St. Louis reached the Netherlands port of Flushing

on the foggy morning of June 17, a tugboat carrying Troper and

18 committee members pulled along the ships port side. Pas-

sengers crowded the rails, waving and shouting, God bless

you! as Troper boarded their ship. Liesl Joseph, who turned 11

that day, stepped forward and read a letter in German, thanking

Troper and the JDC for having saved them from great misery.

Her father, Josef, also gave a speech. As the ship steamed toward

its Antwerp disembarkation point, a delegation representing

Belgium, the Netherlands, France and England met with the

passenger committee in the frst-class lounge to complete the

complicated process of distributing landing documents.

Crowds of cheering people and newspaper photographers

met the St. Louis in Antwerp. Buf and 213 others destined for

Belgium disembarked immediately. Te 181 refugees assigned

to the Netherlands boarded a steamer for Rotterdam. Te Jo-

sephs were bound by freighter for England and the Fishers and

Karliners for France. With mixed emotions, the freighter pas-

sengers watched as the St. Louis, the ship that had been both

home and prison, pulled out of the pier for Hamburg.

For many, freedom was short-lived. In May 1940, Belgium,

the Netherlands and France fell under

Nazi occupation, trapping the 620 refu-

gees sent to those countries. Of these,

254 died at the hands of the Nazis, in-

cluding Karliners parents and sisters.

Tose fortunate enough to be sent to

England survived Hitlers Final Solu-

tion. About half of the 937 passengers

eventually immigrated to America.

Critics have since lambasted Beren-

son for his inability to make a success-

ful deal. And despite moves by Cabinet

members, diplomats and other ofcials

to assist European Jews, U.S. immigra-

tion remained tightly restricted. Te

gov ernments concern that admitting

the St. Louis refugees would open a

food gate for undesirable immigrants

has cast long shadows over the legacy

of the Roosevelt administration.

On the 70th anniversary of the voyage of the St. Louis,

June 6, 2009, the U.S. Senate passed Resolution 111, which

acknowledged the sufering of those refugees caused by the

refusal of the United States, Cuban, and Canadian govern-

ments to provide political asylum. With this resolution,

Ameri ca ofcially recognized its role in turning away 937

German-Jewish refugees in their hour of need. Survivors of

the St. Louis were invited to a special event in Miami Beach

to sign copies of the resolution and accept this national apol-

ogy. Liesl Joseph Loeb, Herbert Karliner and Fritz (now Fred)

Bufwho served in the U.S. Navy during World War II

were among those who attended. n

Barbara D. Krasner teaches writing at William Paterson Univer-

sity. She is the author of Discovering Your Jewish Heritage and

Images of America: Kearnys Immigrant Heritage.

captain gustav schroeder, a lifelong sailor,

was a fervent opponent of the Nazi Party.