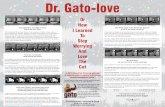

Vol. 2, Issue 2. Sept. 2006. Wild Cat News...The Andean cat is the least-known cat in the western...

Transcript of Vol. 2, Issue 2. Sept. 2006. Wild Cat News...The Andean cat is the least-known cat in the western...

© 2006 The Cougar Network:Using Science to Understand Cougar Ecology.Cover Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

The Cougar Network’s tri-annual publication dedicated to the scientific research of North American wild cats

Wild Cat NewsVol. 2, Issue 2. Sept. 2006.

IN THIS ISSUEJaguars in the Pantanal

Andean Mountain Cats

Project Wild Cats of Brazil

Potential Midwest Cougar Habitat Research Update

Chemical Capture of Free-Ranging Felids

Puma Research - Nowthat you have it, what do you do with it?

Wild Cat News

Puma ResearchNow that you have it, what do you do with it?

By Harley Shaw, Biologist

When Carol Cochran asked if I would participate in this workshop, I had just finished a phone call with a friend who worked for many years as a predator control agent in California. He is a rather independent thinker and home-spun philosopher and always enjoys rattling my cage. We were discussing the recently-published Cougar Management Guidelines, a synthesis of research and management experience that Ken Logan and I, along with 11 other biologists, helped write. While my friend didn’t openly disagree with the guidelines, his com-ment regarding their use was, “Why should we bother? We’ve been man-aging cougars successfully for 100 years without all of this information.Why change now?” His solution is simple – just take out the problem cats, and let the rest take care of them-selves. His question was rhetorical, intended to make me think. He didn’t expect an argument or an answer. But make me think, he did. Should new knowledge always create change?

A host of agencies and universities have been doing research on the puma

in the United States, Canada, and Lat-in America since the mid-1960s, when Maurice Hornocker broke the meth-odology barrier in his Idaho Primi-tive Area study. Over time, more efficient methods of capturing puma, improved radio-tracking equipment and, more recently, population genet-ics and camera traps have contributed to our research abilities. We know a lot more about the basic biology of the species than we did in the 1960s.

At the same time, the conflicts surrounding the puma have changed and grown. In 1970, when I first began working with the puma, the main questions in Arizona involved its numerical status, the effect it was having on livestock and deer, and the effect hunting was having on it. Other states addressed these same ques-tions more or less about that time. As a result of these studies, few people are now worried about the immediate extinction of the puma in the western United States, and we have pretty much defined the circumstances under which they become troublesome with livestock. While these issues still exist, they are no longer the ones that make news. We still struggle over

appropriate regulations for hunting the puma, but these seem to be centered more upon ethics and politics than upon the long-termed welfare of the species. What seems to have most of our attention is the continued move-ment of humans into puma habitat and the resultant conflicts between the two species, including rare but frightening attacks on humans and, conversely, the ongoing loss and fragmentation of habitat. Added to this is the reap-pearance of the species in historic ranges to the East, which has created fear, concern over livestock loss, and conflicts regarding recommended puma hunting in these re-expansion areas. Do we have the knowledge we need to address the new problems that are arising? If so, how do we imple-ment that information, and to take up my California friend’s question, why should we? Can’t we just continue to apply our old tools of control and/or regulated hunting, and leave the rest to nature or fate?

I am convinced that my friend was intentionally, perhaps a little facetiously, presenting a pretty com-mon point of view in wildlife man-agement ranks. Our profession and

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 26

The following article was derived from a speech delivered by the author at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science on April 18, 2006. The forum was a panel discussion involving biologists, ranchers, environmentalists, and resource managers entitled “Sharing a Home with Predators: How Well do Humans and Mountain Lions Co-exist in Colorado?”

Chemical Capture of Free-Ranging Felids

Wild cats come in all sizes, ranging from the diminutive rusty-spotted cat of Asia (1.5 kg) to the 300 kg Siberian tiger. Despite these differences, most cats are physiologically “wired” the same.This is fortunate when faced with the task of chemically immobilizing wild felids because it simplifies drug choices and dosages.

Cats have to be caught for all kinds of reasons. Most cat captures conducted by wildlife management agencies are for research. Usually the

cat needs to be weighed, measured, sexed, and marked with ear tags or transponders. Blood samples are often taken for health screening and DNA analysis. Depending on the research needs, radio collars may be attached for tracking purposes. To conduct all of these operations on an awake cat, well-armed with teeth, claws, and attitude, is challenging at best. When faced with this challenge, people find that drugs are their friends when it comes to handling cats!

Other reasons for catching cats are for translocation/reintroduction to establish new populations or to remove them from places where they shouldn’t be (e.g., the mountain lion

in town). Small to medium-sized cats are usually initially trapped with foothold or box traps and then drugged. Larger cats, such as mountain lions, can be chased by dogs and treed, then darted with drugs.Many of the large African cats are darted over bait or carcasses. Asian tigers are driven by elephants towards hidden persons with dart guns.Siberian tigers are probably the only cats routinely darted from helicopters.

There are two major classes of drugs used for the immobilization of all wildlife: cyclohexanes and opioids. Opioids (often inappropriately called narcotics) are mostly chemical modifications of the morphine

By Terry J. Kreeger, DVM, Ph.D.Supervisor, Veterinary Services Wyoming Game and Fish Dept.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 23

Above: A mountain lion caught in a foothold trap and darted in the hip.

Status Update:

Modeling PotentialCougar Habitat

in Midwestern North America

Cougars are becoming a species of interest to Midwestern wildlife biologists and the general public because of their increasing presence in the region. As confirmed by the Cougar Network, cougar carcasses, scat, and tracks in Midwestern states have increased dramatically during

the past 15 years, suggesting eastward movement of cougars. Recent research has found that cougars can disperse considerable distances, as evidenced by a juvenile male dispersing 1,067 km into Oklahoma from the Black Hills and a juvenile female dispersing 1,336 km within western cougar range. Given the increasing number of confirmations and their long-distance dispersal capability, it is possible that cougars are attempting to re-colonize the Midwest via juvenile dispersal.

Although wildlife biologists will require information to support management, protection, and public education regarding cougar

presence in the Midwest, currently no information is available to assist such efforts. To concentrate on these needs, as reported in the June 2005 issue of the Wild Cat News, efforts are currently being undertaken to provide the first model of cougar habitat in the Midwest by using expert opinion surveys, geospatial data, and a geographic information system (GIS). This article provides a status update on the model’s progress.

Approach to Modeling Potential Cougar Habitat

Habitat models have been created for many carnivore species using

By Michelle A. LaRue Graduate Research Assistant, and Dr. Clayton K. Nielsen Wildlife EcologistCooperative Wildlife Research LaboratorySouthern Illinois University Carbondale (MAL, CKN);Cougar Network (CKN)

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 20

Above: Trailcam photo taken near Savage, Minnesota. Courtesy Kerry Kammann.

Project Wild Catsof Brazil

By Tadeu G. de Oliveira, Biologist, Maranhão StateUniversity - UEMA and Institute Pro-Carnivoros

The American continent houses 12 species of wild felids, of which only three are commonly found in North America. Tropical America, which comprises the zoogeographical province of the Neotropics (coastal and tropical lowland areas of Mexico all the way down to the Straight of Magellan in southernmost Chile and Argentina), on the other hand, harbors 10. These are: ocelot (Leopardus

pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii),little spotted cat (Leopardus tigrinus),Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi),kodkod (Leopardus guigna), pampas cat (Leopardus colocolo), Andean cat (Leopardus jacobitus), jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi), puma (Pumaconcolor), and jaguar (Pantheraonca). Only the puma is characteristic of both areas, and except for the kodkod and Andean cat, all are found in Brazil.

Needless to say, studies on North American felids (puma, bobcat – Lynx rufus – and Canada lynx – Lynx canadensis) make them some of

the best-studied species worldwide.However, in the Neotropical realm, felids are among the least known in the world, with very limited information available regarding their ecology and conservation needs. This holds true even for Neotropical puma. All species “south of the border” are under a series of threats and are considered threatened with extinction in varying degrees in several parts of their range. In Brazil, all are threatened either nationally (most species) or at the state level.

In 2003, Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment, through the National

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 12

Above: The little spotted cat is a native to Brazil. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

The Quest for little-known Cats of the Americas:

SacredCat

of the Andes

By Jim Sanderson, Ph.D.Conservation InternationalWildlife Conservation NetworkSmall Cat Conservation AllianceIUCN Cat Specialist GroupAndLilian Villalba, M.Sc.Alianza Gato AndinoColeccion Boliviana de FaunaIUCN Cat Specialist Group

With exquisite timing, the exciting news reached those in La Paz, Bolivia,

attending a recent meeting of Alianza Gato Andino (AGA), an organization dedicated to conservation efforts of the Andean cat (Oreailurus jacobita)throughout its geographic range in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Perú.

The international model and movie star, Isabella Rossellini, daughter of screen legend Ingrid Bergmann, had donated to AGA half of her $100,000 Disney Wildlife Conservation Award she had received for her tireless efforts to protect wildlife. To all of

those at the AGA meeting, Isabella’s commitment to wildlife conservation and love of Andean cats came as no surprise.

The Andean cat is the least-known cat in the western hemisphere. Gatoandino is also one of only four cats considered Endangered by the IUCN Cat Specialist Group, making it the Americas’ most threatened cat species. Three Asian species – bay cat, snow leopard, and tiger - share this dubious distinction.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 7

Above: A female Andean mountain cat peers from a small cave at the edge of a precipice in Khastor Bolivia. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

Amidst the myriads of sounds under the big night sky of the Pantanal, we strained our ears to identify anything that would denounce the presence of the jaguar on the river bank, just 10 meters from our boat. After the first distant replies to the hoarse, repeated grunts that Fião, a park employee, produced with an oversized, hollow gourd, the animal had remained silent. Some of us were already skeptical that he would come to investigate the potential invasion of its haunts by an unknown jaguar. All of a sudden, an unlikely sound came from the bank like a low, harsh miaow that Fião and I identified as a close-range vocalization, an appeasement

contact. Fião shined his torch, and partly hidden in the entangled vegetation, we saw an adult male jaguar (below). The animal avoided eye contact with the light, lowering

his head almost to the ground. One moment he was there, omnipresent, and in the next, he was gone. We heard nothing more. Only then, it seemed, we all resumed breathing. It

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 3

Jaguars in the Pantanal of BrazilBy Peter G. Crawshaw Jr., Biologist Brazilian Institute for the Environment (IBAMA)

Male jaguar, Pantanal National Park, 20 February 2006 (José Luiz Menezes/Peter Crawshaw Jr.).

Vol. 2, Issue 2. September 2006.IN THIS ISSUE

Jaguars in the Pantanal By Peter G. Crawshaw Jr., Biologist

Andean Mountain CatsBy Jim Sanderson, Ph.D., and Lillian Villalba, M.Sc.

Project Wild Cats of BrazilBy Tandeu G. de Oliveira, Biologist

Potential Midwest Cougar Habitat UpdateBy Michelle A. LaRue, Graduate Research Assistant, and Dr. Clayton K. Nielson, Wildlife Ecologist

Chemical Capture of Free-Ranging FelidsBy Terry J. Kreeger, DVM, Ph.D.

Puma Research - what do you do with it?By Harley Shaw, Biologist

3

7

12

20

23

26

© 2006 The Cougar Network: Using Science to Understand Cougar Ecology

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Clay Nielsen • ILHarley Shaw • NMKen Miller • MAMark Dowling • CTBob Wilson • KS_______

SCIENTIFIC ADVISORS

Chuck Anderson • WYAdrian P. Wydeven • WIBill Watkins • MBRon Andrews • IADarrell Land • FLDave Hamilton • MOJay Tischendorf • MT_______

EDITOR

Scott Wilson

Amidst the myriads of sounds under the big night sky of the Pantanal, we strained our ears to identify anything that would denounce the presence of the jaguar on the river bank, just 10 meters from our boat. After the first distant replies to the hoarse, repeated grunts that Fião, a park employee, produced with an oversized, hollow gourd, the animal had remained silent. Some of us were already skeptical that he would come to investigate the potential invasion of its haunts by an unknown jaguar. All of a sudden, an unlikely sound came from the bank like a low, harsh miaow that Fião and I identified as a close-range vocalization, an appeasement

contact. Fião shined his torch, and partly hidden in the entangled vegetation, we saw an adult male jaguar (below). The animal avoided eye contact with the light, lowering

his head almost to the ground. One moment he was there, omnipresent, and in the next, he was gone. We heard nothing more. Only then, it seemed, we all resumed breathing. It

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 3

Jaguars in the Pantanal of BrazilBy Peter G. Crawshaw Jr., Biologist Brazilian Institute for the Environment (IBAMA)

Male jaguar, Pantanal National Park, 20 February 2006 (José Luiz Menezes/Peter Crawshaw Jr.).

was as if we all had been in a trance, a magical feeling of elation that lasted just a few seconds.

This had been the third night in a row that we had gone out at night, by boat, to attract jaguars by imitating their characteristic vocalization. On the first night, we had attracted what might have been this same animal a

few kilometers upriver, but a restless pilot on our boat had scared the animal away. Overall, of the four nights that we called, we had replies on three, and in two the animal had approached. Even considering that it could have been the same jaguar in both nights, I was still pretty satisfied with the results. I decided to use this

technique as an additional method to estimate relative abundance of jaguars in the Pantanal National Park and the surrounding private reserves that compose the World Heritage Site of the Pantanal (left), declared by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2000.

The place was not new to me. In 1978, when working with world-renowned scientist George Schaller in the first-ever jaguar study, I had lived in the nearby Acurizal ranch, now one of the private reserves owned by the Fundação Ecotrópica. That study, after only 14 months of following two jaguars and one puma with radio-telemetry, had to be halted. A deal to buy the ranch between the Brazilian Institute for Forest Development (IBDF, the federal environmental agency that partly sponsored the study – and hired me) and the owner broke up. Two other jaguars had been killed to force our project out of the ranch (Schaller, 1978; Schaller and Crawshaw, 1980). We had to resume the study in other parts of the Pantanal (Schaller et al, 1984; Crawshaw and Quigley, 1991; Quigley and Crawshaw, 1992).

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 4

Beneath the Amolar mountain range - Serra do Amolar - which borders Bolivia, the flatness of the Pantanal consists of flat marshes, grasslands, and forests.

The Pantanal consists of a vast floodplain formed by the Paraguay river and its tributaries, some 140,000 km2 in size, in southwestern Brazil. The vegetation is characterized by marshes and seasonally flooded grasslands, interspersed with palm stands, meandering riverine forests, and islands of varying sizes of deciduous to semideciduous forests (Prance and Schaller, 1982). Cattle ranching was introduced in the Pantanal more than 200 years ago and since that time has been the main economic activity of the region. The whole area has had a history of large cattle ranches, usually no smaller than 50 km2 and a few exceeding 3,000 km2.

Relentless persecution from the commercial hunting for spotted skins before the banning of hunting in Brazil in 1967, as well as control

of jaguar livestock depredation from cattle ranchers, had already wiped out jaguars from large areas of the Pantanal. In 1978, significant populations were restricted to three areas, of which two were where our studies were conducted (Schaller and Crawshaw, 1980; Crawshaw and Quigley, 1991). Elsewhere, jaguar sign was exceptionally rare.

However, in the last 15 to 20 years, the species seems to have made a remarkable comeback, apparently because of a retraction of the cattle industry, combined with some high flood years (Crawshaw, 2002). As a result, fewer people remain in the back country, working and living at the ranches, and cattle that survived the floods were left in a feral state, providing additional food for the jaguar. Also, native species such as caiman and capybaras increased

in number and provided ample food. Ecotourism has since been incorporated in an increasing number of ranches as an additional source of income. Jaguar sightings are more common now than in the early 80s.

I will be conducting an evaluating survey in the area in the coming months. If high jaguar density is indeed confirmed, I will invest the next four to five years of my life in re-establishing a research project to conclude the study so sadly interrupted almost 30 years ago. One advantage of the present situation is that cattle ranching has practically stalled in the whole region of the Park, which means no persecution from ranchers. This will be an important differential to this study, in relation to other ongoing jaguar research projects in the Pantanal. Sandra Cavalcanti, Leandro Silveira, and Fernando

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 5

Azevedo are presently studying jaguar ecology and conservation, all three studies being carried out in heavily-ranched areas in the southern Pantanal. Despite the fact that future conservation of the jaguar will very likely depend on a reasonable level of coexistence with cattle ranching in the Pantanal, it will be a treat to be able to study the ecology and behavior of this wonderful cat untroubled by direct interference of livestock and man.

References Cited

Crawshaw Jr., Peter G. 2002. Mortalidad inducida por humanos y conservación de jaguares: el Pantanal y el Parque Nacional Iguaçu en Brasil. IN: Medellin, R. A., Equihua, C., Chetkiewicz, C.L.B., Crawshaw Jr., P.G., Rabinowitz, A. Redford, K. H., Robinson, J. G., Sanderson, E., and Taber , A. B. (eds.) El Jaguar en el nuevo milenio. Univ. Nacional Autonoma de Mexico/Wildlife Conservation Society. Mexico DF: 451-464.

Crawshaw Jr., Peter G. and Quigley, H.B. 1991. Jaguar spacing, activity, and habitat use in a seasonally flooded environment in Brazil. J. Zool. (London), 223: 357-370.

Quigley, Howard B. and Crawshaw Jr., P.G. 1992. A conservation plan for the jaguar (Panthera onca) in the Pantanal region of Brazil. Biological Conservation 61: 149-157.

Schaller, G.B. 1978. Epitaph for a jaguar. Animal Kingdom Magazine., New York Zoological Society, NY.

Schaller, G.B., H.B. Quigley, and P.G. Crawshaw Jr. 1984. Biological investigations in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Nat. Geog. Res. Rep. 1976 Projects: 777-792.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 6

SacredCat

of the Andes

By Jim Sanderson, Ph.D.Conservation InternationalWildlife Conservation NetworkSmall Cat Conservation AllianceIUCN Cat Specialist GroupAndLilian Villalba, M.Sc.Alianza Gato AndinoColeccion Boliviana de FaunaIUCN Cat Specialist Group

With exquisite timing, the exciting news reached those in La Paz, Bolivia,

attending a recent meeting of Alianza Gato Andino (AGA), an organization dedicated to conservation efforts of the Andean cat (Oreailurus jacobita)throughout its geographic range in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Perú.

The international model and movie star, Isabella Rossellini, daughter of screen legend Ingrid Bergmann, had donated to AGA half of her $100,000 Disney Wildlife Conservation Award she had received for her tireless efforts to protect wildlife. To all of

those at the AGA meeting, Isabella’s commitment to wildlife conservation and love of Andean cats came as no surprise.

The Andean cat is the least-known cat in the western hemisphere. Gatoandino is also one of only four cats considered Endangered by the IUCN Cat Specialist Group, making it the Americas’ most threatened cat species. Three Asian species – bay cat, snow leopard, and tiger - share this dubious distinction.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 7

Above: A female Andean mountain cat peers from a small cave at the edge of a precipice in Khastor Bolivia. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

The Andean cat was described to science by Cornalia, an Italian, in 1865. However, so little was known of this high Andes specialist that most natural history books written before 1900 neglected to include it when describing the world’s living cat species.

By 1998, several Andean cats had been photographed, and accounts of two encounters were published. Remarkably, both publications stated

that the cat seemed to ignore the presence of human observers who were able to approach the cat and obtain very clear photographs.

In mid-1998 a photograph, taken by a tourist visiting Salar de Surire in northern Chile, of what was clearly an Andean cat was provided to Jim Sanderson by Agustin Iriarte working in wildlife conservation in the Chilean government. This photograph led to another close encounter of the

third kind in November 1998. This time the encounter was between an Andean cat and Sanderson, a member of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group (Sanderson & Iriarte 1999 Cat News). Supported by a National Geographic Society grant, Sanderson settled in at Salar de Surire in October 1998 to look for an orange metal pole that appeared in the photograph of the Andean mountain cat. As fate would have it, the pole was just behind his accommodation, the so-called “ice box,” a dilapidated trailer in a valley 4,300 meters above sea level, surrounded by snow-capped peaks.

After setting more than a dozen live traps, on November 12 the daily routine of checking these traps was suddenly broken when Sanderson followed and photographed a male Andean cat for more than four hours. However, the cat eluded his live traps.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 8

An Andean cat peeks over a rock in Salar de Surire, Chile. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

A Mountain viscacha stands at alert in Salar de Surire, Chile. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

considered wild cats sacred animals because they are the symbol of abundance and fertility, but the Native Americans also use them dead and dried in ritual ceremonies related to crops and native herds. It would not be until later that the published remarks and the significance of superstitious beliefs would come together to galvanize action.

At every opportunity, from every platform, researchers talked about the plight of the Andean cat, but because

During this encounter he was able to approach the cat to within three meters, and in fact the cat ignored his presence. The cat even licked itself and napped while he approached it.

Andean local people living in nearby small villages reported that wild cats were now very rare, that none had been seen in quite some time, and that the cats were likely no longer present in the area. They asked to be notified if any were seen. When asked how they obtained the skins of the cat, women invariably gave the same response: we drop a rock on them.

The profound significance of so simple a statement – we drop a rock on them – would come back to haunt Sanderson.

Similar information was obtained from interviewed local people when Lilian Villalba and her colleague Nuria Bernal were working during 1998 and 1999, looking for the Andean cat at different Andean localities in Bolivia.

One piece of news common to both countries was observed: Native Americans of the high Andes

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 9

Below: A view of the “rocky valley” of Khastor (Potosi, Bolivia). Photograph by Lilian Villalba.

there were just three well-documented encounters and virtually no hard data, scientific publications were not going to aid the case. Without data, we were just ordinary citizens with opinions. No data meant no chance of further funding, and no funding assured that no data or conservation measures would be forthcoming.

In 1999, researchers from the four Andean cat range countries gave birth to the Andean Cat Conservation Committee, predecessor of AGA,

Geographic range map of Andean mountain cat showing Salare de Surire, Chile and Khastor, Bolivia.

and diverse cooperative actions were carried out in the following years. In 2003, these cross-border conservation efforts shifted into high gear when Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN), a not-for-profit organization founded by Akiko Yamazaki, Charlie Knowles, and John Lukas, chose to

support Andean cat conservation in all four range countries.

April 2004 was a remarkable month for the members of AGA. During an AGA meeting in Arica-Chile, the first Andean cat conservation Action Plan was discussed. In Jujuy Province, Argentina, two encounters occurred:

the first photos of an Andean cat were taken (Lucherini et al., 2004 Cat News), and in Bolivia, as a part of a radio telemetry study, the first ever Andean cat was live captured (Delgado et al. 2004 Cat News).

Ten hours south of Uyuni, Bolivia, and just north of the Argentinean frontier lies Khastor, an uninhabited region of salt lakes, and bofedales – grassy areas supplied by glacial waters – traditionally used as llama summer feedings grounds. Lilian Villalba and Eliseo Delgado, a park guard, have been working since 2001 in Khastor and have camera trapped three Andean cats. During the first months of 2004, a female Andean cat had been seen using a small cave just over the edge of a precipice and was habituated to get in to an inactive live trap.

Early on the morning of April 25, 2004, the trap door of a live trap was closed and inside was an Andean cat; one day before, the trap had

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 10

Jim Sanderson shows school children a video of the Andean cat.

Below: Constanza Napolitano, Lilian Villalba with the Andean cat, and Eliseo Delgado. Khastor. Bolivia. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

been baited just before sunset. Using a light drug dose, the cat, an adult female weighing 4.5 kg, was sedated and a 60 gm radio-collar was fitted on her. The group was observed by a male Andean cat just a short distance away. Her release went smoothly, and nine months of radio-tracking at 4,200 to 4,600 m followed.

Theory says that the home range of a cat is proportional to its body weight and elevation. Though the Andean cat is a small cat, it lives at high elevation and so has a very large home range. In this area the main prey is the mountain viscacha (Lagidium viscaccia), colonial rodents, weighting about 1 kg.

Results of the radio-telemetry effort showed that the cat spends a few days hunting and resting at a viscacha colony before it moves on to another colony that might be several kilometers distant. Researchers now have a much better understanding of the landscape characteristics that support an adequate prey base and therefore minimum requirements for the Andean cat. They also know where to look for caves and fecal deposits.

AGA groups in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru continue to document the presence of Andean cats with camera traps and other survey techniques and have improved the

range map of the Andean cat using molecular analysis of fecal material.

AGA has also produced educational material for schools within the geographic range of the Andean cat and hired teachers to visit schools to bring the conservation message to children whose influence on their parents should not be underestimated. Consultations with village leaders regarding conservation efforts is also producing positive results and helping to reduce Andean cat killings.

The high Andean Native American cultures such as the Aymara may well be facing cultural extinction themselves. Through improved radio and television reception, realization that a very different and very appealing lifestyle can be had at lower elevations has prompted many of their children to leave as soon as they are able and never return. Without a written language, their history, life experiences, and legends cannot be recorded in their own words.

With continued education programs the Andean mountain cat’s future will likely not be threatened by “dropping rocks.” With vital support provided by WCN day by day, the battle to conserve Andean cats in their native habitat is moving slowly in favor of science. But this does not give pause to relax because a new and more widespread threat has already begun to evidence itself. The glaciers that feed the bofedals, streams, and rivers that are the life blood of the Andes are shrinking. The Andean cat has apparently survived direct persecution by humans armed only with rocks. Will it survive modern human indirect assault? Continued conservation efforts for the western hemisphere’s most endangered cat, the Andean cat, remain essential.

For more information, visit: www.wildnet.org and www.smallcats.org.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 11

Another picture of the Andean mountain cat female from within a small cave. Photograph by Jim Sanderson.

Project Wild Cats of Brazil

By Tadeu G. de Oliveira, Biologist, Maranhão State University - UEMA and Institute Pro-Carnivoros

The American continent houses 12 species of wild felids, of which only three are commonly found in North America. Tropical America, which comprises the zoogeographical province of the Neotropics (coastal and tropical lowland areas of Mexico all the way down to the Straight of Magellan in southernmost Chile and Argentina), on the other hand, harbors 10. These are: ocelot (Leopardus

pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii), little spotted cat (Leopardus tigrinus), Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi), kodkod (Leopardus guigna), pampas cat (Leopardus colocolo), Andean cat (Leopardus jacobitus), jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi), puma (Puma concolor), and jaguar (Panthera onca). Only the puma is characteristic of both areas, and except for the kodkod and Andean cat, all are found in Brazil.

Needless to say, studies on North American felids (puma, bobcat – Lynx rufus – and Canada lynx – Lynx canadensis) make them some of

the best-studied species worldwide. However, in the Neotropical realm, felids are among the least known in the world, with very limited information available regarding their ecology and conservation needs. This holds true even for Neotropical puma. All species “south of the border” are under a series of threats and are considered threatened with extinction in varying degrees in several parts of their range. In Brazil, all are threatened either nationally (most species) or at the state level.

In 2003, Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment, through the National

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 12

Above: The little spotted cat is a native to Brazil. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

The Quest for little-known Cats of the Americas:

Environmental Fund (FNMA), launched two programs to support studies on its threatened species:

1. Category I – basic research towards the elaboration of a conservation action plan (for species with limited information).

2. Category II – to implement conservation action plans.

A project on the little spotted cat was submitted and approved for category I: “Studies on the biology, distribution, and conservation status of the little spotted cat in Brazil.” The ultimate goal was to elaborate a conservation action plan for natural populations of this small felid in Brazil. The proposal was integrated, joining together all (the very few) researchers and their field studies that were currently ongoing with the species in Brazil. Initially, 14 researchers and 10 institutions were involved in this endeavor. This small cat is currently the main focus, but the

project greatly expanded to include all other felids in all Brazilian biomes from north to south, including the Amazon and Atlantic rainforests, savannas, semi-arid scrub, pampas, and mixed Araucaria (pine) forests.

Then it became “Projeto Gatos do Mato – Brasil” i.e., Project Wild Cats of Brazil. Wild Cats of Brazil is a large-scale, multidisciplinary effort to study Brazilian felids. It was launched in July 2004, and as an umbrella project, it now involves 23 researchers and 11 institutions from north to south.

The project hopes to enlighten current small cat knowledge and provide a baseline for their ecology and conservation. As such, the project will focus on home range, habitat use, food requirements, distribution, reintroduction, genetic makeup, population estimates, reproductive biology, disease, livestock depredation, and conservation. Some topics that have never been attempted will be of a pioneering nature, including verification of the re-introduction of captive-born animals (to be used as a tool for small felid conservation). The project is geographically the largest of its kind for wide-ranging species in South America.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 13

Above: Melanistic Geoffroy’s cats, female (Bugra) and her kitten (Sombra). This population, which is being studied by camera-trapping and radio-telemetry, was originally all spotted, and after animals were shot, it was replaced by an all melanistic and currently is partly spotted and partly melanistic. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Below: Geoffroy’s cat has a limited distribution in Brazil, being restricted to Rio Grande do Sul State. This more “temperate” species seems to be the dominant small felid in the southern cone. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Objectives:

• Conduct ecological (telemetry) studies to determine home range, activity patterns, food habits, habitat use, daily movements, etc. of the smaller species;

• Evaluate the potential for re-introduction of captive-born or raised individuals as a management tool for the

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 14

conservation of small felids;

• Assess the geographic distribution, range, and genetic makeup of the populations of the little spotted cat;

• Verify the occurrence of hybrids with other Neotropical felids, within the populations of little spotted cat/pampas cat/Geoffroy’s cat;

• Assess species community composition and density estimates for all Brazilian biomes;

• Understand the basic issues of the smaller species’ reproductive biology;

• Identify diseases affecting wild and captive populations;

• Determine the main threats and the conservation status for the different areas of Brazil.

Ecological data on species community composition and abundance estimates are being gathered from camera trapping studies using locally-made cameras (two of the models developed by team members). This has proven to be highly effective with a cost/benefit ratio much better than traditional camera trap brands. Data on home range, movement, and daily activity patterns come from radio-telemetry (some information has also been gathered from camera traps) and diet from scat analysis. Genetic studies focus on determining significant evolutionary units of little spotted cat and the occurrence of hybrids. Distribution records combine those of museum collections with field observations, whereas reproductive biology information is being collected from zoo specimens. To evaluate the viability of captive-raised smaller felids as a management tool (for re-introduction programs), animals under study are being adapted for release in the wild through predatory training. Animals considered apt will be released and monitored to evaluate this procedure as a future tool for conservation of smaller wild felids.

Left: The author placing a radio-collar on a male (Maragato) little spotted cat. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 15

Jaguarundi, along with other small felids, are part of the reintroduction pro-gram of Project “Gatos do Mato – Brasil.” Captive-born or raised individuals are readapted for release back in the wild through predatory training. The project seeks to assess the viability of reintroductions of captive-born/raised individuals as a future tool for conservation. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Procedures follow those recommended by the IUCN/SSC/Re-introduction Specialist Group. Evaluations for “threats” assess the intensity of various factors, through the percentage of a particular area under impact. Evaluations for “conservation status” combine all information gathered from natural populations.

Preliminary findings are now being published in scientific journals. Correspondingly, the presence of little spotted cats in the Amazon basin has been confirmed, helping to unravel the myth of their presence. So far, there are more than 214 localities comprising all eco-regions (except for the pampas of Brazil) that hold spotted cats – their range evaluation included all other countries. A population of the pampas cat in an area considerably out of its current known range (see map to right), in the northern part of the country, has just been discovered. Scat collection for diet study is considerably large (>500 samples each) for some areas.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 16

Pampas cats were unknown from Maranhão state in northern Brazil. The nearest known area for the species was 500 km south. This record considerably expanded the species range. In the savannas of Mirador State Park, the first ever species’ density estimate is coming out. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Above: A map showing the field study sites of Project “Gatos do Mato – Brasil” throughout Brazilian biomes from north to south. © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 17

Little spotted cat, along with other small felids, are part of the reintroduction program of Project “Gatos do Mato – Brasil”. Captive born or raised individuals are readapted for release back in the wild through predatory training. We want to assess the viability of reintroductions of captive born/raised individuals as a future tool for conservation. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

The first camera-trapping results are also proving exciting, with preliminary density estimates for little spotted cat, margay, Geoffroy’s cat, pampas cat, and jaguarundi. This has never been done, at least with camera trapping (in the case of jaguarundi). Estimates have also been made for ocelots. Results so far have shown that ocelots reach higher numbers than the smaller species. But, most importantly, this has a significant impact for conservation. Given their density estimates, areas needed for their long-term survival (ca. 5,000 individuals for more than 40 generations) are considerably large. For ocelots, areas should be no smaller than 13,000 km2 and for the smaller species 20,000 km2 in areas where such cats might be considered “common.” Note – this does not suggest the same areas for ocelots and smaller cats. However, in less favorable locations (which comprise most of their range), the area needed to ensure their survival would reach 250,000 km2 or more.

A look at small cat community composition is also proving interesting. Ocelots tend to be the

dominant and most abundant species. We theorize that ocelot and jaguar numbers might effect those of little spotted cats and margays. This “ocelot effect” also has conservation implications. The largest protected areas (almost all of which is located in the Amazon), which also harbor good ocelot populations, would thus not be the best areas for large populations of at least some of the smaller species,

especially the little spotted cat. This is a similar situation to that of the lion and cheetah in Africa (where lions are abundant, i.e., within protected areas, cheetahs are not).

In the radio telemetry effort to date, the following have been collared: two little spotted cats, one margay, three jaguarundis, and two Geoffroy’s cats. Animals are being monitored in a forest and agricultural

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 18

Although margay ranges from Mexico through northern Argentina and south-ern Brazil, it is very poorly known. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

The southern-most population of jaguars in Brazil is found at Turvo State Park, where camera-trapping has shown that individuals cross the border with Argentina, attesting to the need of transnational conservation actions/efforts. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

mosaic. By doing so, researchers will be able to know how the cats cope in this landscape (a mosaic which dominates much of southern-southeastern Brazil, and more and more all over the country).

So far, researchers have detected that forest cover is of paramount importance at least for the little

spotted cat, margay, and jaguarundi. Findings on the predatory training

of captive-raised specimens are also quite interesting, with a far better response than expected. Notably, natural hybrids have been detected within some species. As the days go by and as findings are coming out, project actions and participation are

increasing. However, phase one is about to end, and the quest for the project’s continuation (phase two) is on. This phase hopes to answer some of the questions about the natural history of the little known Neotropical felids.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 19

Female ocelot from Maranhão state northern Brazil. Photograph © Wild Cats of Brazil Project.

Status Update:

Modeling Potential Cougar Habitat

in Midwestern North America

Cougars are becoming a species of interest to Midwestern wildlife biologists and the general public because of their increasing presence in the region. As confirmed by the Cougar Network, cougar carcasses, scat, and tracks in Midwestern states have increased dramatically during

the past 15 years, suggesting eastward movement of cougars. Recent research has found that cougars can disperse considerable distances, as evidenced by a juvenile male dispersing 1,067 km into Oklahoma from the Black Hills and a juvenile female dispersing 1,336 km within western cougar range. Given the increasing number of confirmations and their long-distance dispersal capability, it is possible that cougars are attempting to re-colonize the Midwest via juvenile dispersal.

Although wildlife biologists will require information to support management, protection, and public education regarding cougar

presence in the Midwest, currently no information is available to assist such efforts. To concentrate on these needs, as reported in the June 2005 issue of the Wild Cat News, efforts are currently being undertaken to provide the first model of cougar habitat in the Midwest by using expert opinion surveys, geospatial data, and a geographic information system (GIS). This article provides a status update on the model’s progress.

Approach to Modeling Potential Cougar Habitat

Habitat models have been created for many carnivore species using

By Michelle A. LaRue Graduate Research Assistant, and Dr. Clayton K. Nielsen Wildlife EcologistCooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory Southern Illinois University Carbondale (MAL, CKN);Cougar Network (CKN)

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 20

Above: Trailcam photo taken near Savage, Minnesota. Courtesy Kerry Kammann.

animal location data, remotely-sensed land cover data, and multivariate statistics within a GIS. These models typically rely upon empirical data regarding species occurrence or habitat use. However, cougars have been extirpated from the Midwest for more than 100 years, so obtaining empirical data regarding habitat use is not possible. To overcome this problem, expert opinion surveys are being used to provide information regarding cougar habitat in the Midwest.

Our methods will include obtaining expert opinion regarding cougar habitat, evaluating the responses through a multi-criteria evaluation, and then transforming these data into numerical form, where it can be implemented in a GIS. Use of expert-opinion models has been

evaluated by biologists studying the habitat needs of other large carnivores and has shown that expert opinion closely reflected data gathered by radio-telemetry. GIS applications will be used to produce maps of cougar habitat by combining the expert opinion surveys and spatial analysis of existing landscape information.

Potential cougar habitat and dispersal corridors over a large portion of the Midwest are being modeled, including the states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota (Figure 1). These states were selected because of the number of cougar confirmations in the region, proximity to existing western cougar populations, and potential dispersal corridors, such as rivers.

Expert Opinion Survey

To gain expert knowledge, literature and expert assistance will be used to develop a survey regarding potential habitat requirements of cougars in the Midwest. The survey consists of several questions regarding pair-wise comparisons of the following habitat factors: human density, distance to water, distance to roads, slope, and cover type (Figure 2). Survey participants will be asked to score habitat variables in order of importance to cougars in the Midwest, based upon personal experience and expert knowledge of cougar ecology. The survey will be sent to 29 western cougar biologists and furbearer biologists with knowledge of Midwestern landscapes.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 21

Figure 1: Study area for modeling potential cougar habitat in Midwestern North America.

Multi-Criteria Evaluation and Habitat Modeling

To model potential cougar habitat, raw data will be transformed into GIS layers, which is done through evaluating the multiple criteria in the survey. Upon receipt of completed surveys, responses will be evaluated by determining the relative importance of each habitat factor. Responses for each factor will be averaged and assigned a weight. These weights will subsequently be used in the modeling process within a GIS to create a spatial map of potential habitat suitability for cougars. The map will clearly classify areas of good versus poor potential habitat along a gradient of classified values, which will be the most important product of the research.

Importance of Our Research

A land cover map will display areas of potential habitat for cougars should they eventually re-colonize the Midwest. Nobody knows for sure whether this will happen. However, given that other large carnivores are successfully re-colonizing their former range in North America, this research will provide an important planning tool for the future. For example, white-tailed deer would likely be the primary prey for cougars. Given the importance of deer to humans, knowledge of potential distribution of cougars relative to deer will be essential. Second, because cougars are top predators, they will likely compete with wolves, coyotes, and bobcats, which could alter population characteristics, behaviors, and distribution of prey. Analyses will provide an important assessment of areas where significant overlap with sympatric carnivores may occur. Finally, potential cougar presence in the Midwest will most

certainly concern the public. Data interpretation will indicate where cougars may become established near centers of human populations or areas of livestock operations, thereby proving an important educational and planning tool to address human-cougar conflicts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Summerlee Foundation, Shared

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 22

Earth Foundation, and the Graduate School and Cooperative Wildlife Research Laboratory at Southern Illinois University Carbondale for funding this project. C. Anderson and H. Shaw provided assistance with developing the expert opinion survey. D. Smith provided an image of the study region. We also acknowledge M. Dowling, K. Miller, and B. Wilson of the Cougar Network for their assistance and support in this research.

Figure 2: Land cover map of Arkansas.

Arkansas Land Cover

140 70 0 140

Kilometers

Developed/Barren

Deciduous Forest

Evergreen Forest

Mixed Forest

Shrubs, Orchards

Grass

Crops, Pastures

Wetlands

N

Chemical Capture of Free-Ranging Felids

Wild cats come in all sizes, ranging from the diminutive rusty-spotted cat of Asia (1.5 kg) to the 300 kg Siberian tiger. Despite these differences, most cats are physiologically “wired” the same. This is fortunate when faced with the task of chemically immobilizing wild felids because it simplifies drug choices and dosages.

Cats have to be caught for all kinds of reasons. Most cat captures conducted by wildlife management agencies are for research. Usually the

cat needs to be weighed, measured, sexed, and marked with ear tags or transponders. Blood samples are often taken for health screening and DNA analysis. Depending on the research needs, radio collars may be attached for tracking purposes. To conduct all of these operations on an awake cat, well-armed with teeth, claws, and attitude, is challenging at best. When faced with this challenge, people find that drugs are their friends when it comes to handling cats!

Other reasons for catching cats are for translocation/reintroduction to establish new populations or to remove them from places where they shouldn’t be (e.g., the mountain lion

in town). Small to medium-sized cats are usually initially trapped with foothold or box traps and then drugged. Larger cats, such as mountain lions, can be chased by dogs and treed, then darted with drugs. Many of the large African cats are darted over bait or carcasses. Asian tigers are driven by elephants towards hidden persons with dart guns. Siberian tigers are probably the only cats routinely darted from helicopters.

There are two major classes of drugs used for the immobilization of all wildlife: cyclohexanes and opioids. Opioids (often inappropriately called narcotics) are mostly chemical modifications of the morphine

By Terry J. Kreeger, DVM, Ph.D.Supervisor, Veterinary Services Wyoming Game and Fish Dept.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 23

Above: A mountain lion caught in a foothold trap and darted in the hip.

molecule. They are extremely potent drugs, capable of immobilizing the largest of animals, and they should never be used on felids. Cats often have severe reactions, such as hyperexcitability and convulsions, when given opioids. Fortunately, the cyclohexane class of drugs is very felid-friendly, being both safe and efficacious.

Ketamine and tiletamine are two cyclohexane drugs most often used on cats. Both are modifications of the drug phencyclidine. Phencyclidine (a.k.a. PCP, angel dust) was the first cyclohexane drug used for wildlife capture. It was very potent and very effective. Unfortunately, human abuse caused its demise for wildlife work. Because they are related to phencyclidine, ketamine and tiletamine are controlled substances requiring special licensure from the Drug Enforcement Agency. Nonetheless, they are readily available from any veterinarian.

Speaking of veterinarians, by federal regulations, all of these drugs used to immobilize wildlife are prescription drugs that can only be used by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. This does not mean that people have to have a veterinarian by their side in the field, but they do need to consult with one to both obtain and use immobilizing drugs.

The cyclohexanes usually should be combined with a tranquilizer to diminish undesirable side effects. When ketamine is used alone in cats, it can cause convulsions upon induction and rough recoveries characterized by incoordination, thrashing, and head banging. Ketamine is usually combined with tranquilizers such as xylazine or medetomidine. Both of

these tranquilizers can be reversed, or antagonized, which can shorten the time the animal is immobilized. Tiletamine comes pre-packaged with a tranquilizer called zolazepam; no other tranquilizer needs to be added. The tiletamine-zolazepam combination also comes in powder form and can be concentrated by simply adding a small amount of sterile water to bring it into solution. All the wild cats in the world can be effectively immobilized using one of these drug combinations. A comprehensive listing of drug dosages for wild cats can be found in the Handbook of Wildlife Chemical Immobilization.

Equipment to deliver drugs to cats include hand-held syringes for cats caught in box traps; pole syringes for cats in foothold traps; and blow pipes, dart pistols, or rifles for cats in trees or over bait. Small- to medium-sized felids should probably only be darted with blow pipes firing lightweight, compressed air-powered plastic darts

(e.g., Dan-Inject® or Telinject®). Blow pipes powered by carbon dioxide (instead of the lungs) are very useful for most felid immobilizations. They can be adjusted for distance and are acceptably accurate to ranges from 1

to 20 meters, but are capable of only delivering smaller volume darts (i.e., ≤ 3 ml).

Larger cats (> 25 kg) can be safely darted with dart rifles or pistols firing darts that use black powder to develop the explosive force to inject drug contents. These explosive darts (e.g., Pneu-Dart®, Cap-Chur®) deliver the drug into the animal in probably less than one-thousandth of a second. This force invariably causes subcutaneous and muscular hemorrhage. Thus, their use should probably be restricted to cats with sufficient muscle

mass to sustain such injury. The best dart rifles for felids are adjustable, carbon dioxide-powered rifles (e.g., Dan-Inject® or Telinject®). They are capable of delivering a variety of dart sizes (up to 10 ml) at ranges from 5 to 45 meters. They are, however, quite expensive ($1,500 to $3,000). Dart rifles using .22 blank cartridges

Adjustable, carbon dioxide-powered blow pipes firing light-weight plastic darts are very useful for felid immobilizations.

A European lynx being monitored by a pulse oximeter. Note that the color of the tongue indicates that the animal is breathing fine. Photo by Jon Arnemo.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 24

to propel the dart should be used judiciously because of their potential to cause severe injury if overpowered. Rifles capable of varying the propulsive force of the .22 blank are preferred. Darts should be equipped with barbed needles measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm. Barbed needles are recommended because they cannot be easily dislodged, thus assuring that all of the drug is delivered.

Once immobilized, eyes should be covered and preferably treated with an ophthalmic ointment or saline because the eyes invariably remain open with the cyclohexane drugs. Respiration and rectal temperatures should be continuously monitored; pulse and cardiac function are rarely impacted by these drugs. Pulse oximeters, which measure the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin, are useful devices to monitor respiration, but are not absolutely necessary. The color of the cat’s tongue or gums is a fairly good indicator of respiration. The color should be pink to pale pink; if whitish, gray, or (worse) blue, the cat needs oxygen.

Simple chest compressions every five seconds invariably solve this crisis. Rectal temperatures should be 97 º F to 104º F (36 º C to 40º C). If the animal is cool, warm it with an outside source of heat (don’t just cover it) and if hot, cool it with water or isopropyl alcohol. Always give antibiotics to cats that have been darted to prevent infection.

Fortunately, felids are fairly easy animals to anesthetize. They tolerate drugs well and adverse reactions are rare. Immobilizing drugs should be part of the armamentarium of any professional biologist working with these species.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 25

Above: The author with a mountain lion that had been trapped, then immobilized with ketamine and medetomidine.

Below: The first free-ranging Siberian tiger both anesthetized with ketamine-medetomidine and fitted with a Global Positioning System collar.

Puma ResearchNow that you have it, what do you do with it?

By Harley Shaw, Biologist

When Carol Cochran asked if I would participate in this workshop, I had just finished a phone call with a friend who worked for many years as a predator control agent in California. He is a rather independent thinker and home-spun philosopher and always enjoys rattling my cage. We were discussing the recently-published Cougar Management Guidelines, a synthesis of research and management experience that Ken Logan and I, along with 11 other biologists, helped write. While my friend didn’t openly disagree with the guidelines, his com-ment regarding their use was, “Why should we bother? We’ve been man-aging cougars successfully for 100 years without all of this information. Why change now?” His solution is simple – just take out the problem cats, and let the rest take care of them-selves. His question was rhetorical, intended to make me think. He didn’t expect an argument or an answer. But make me think, he did. Should new knowledge always create change?

A host of agencies and universities have been doing research on the puma

in the United States, Canada, and Lat-in America since the mid-1960s, when Maurice Hornocker broke the meth-odology barrier in his Idaho Primi-tive Area study. Over time, more efficient methods of capturing puma, improved radio-tracking equipment and, more recently, population genet-ics and camera traps have contributed to our research abilities. We know a lot more about the basic biology of the species than we did in the 1960s.

At the same time, the conflicts surrounding the puma have changed and grown. In 1970, when I first began working with the puma, the main questions in Arizona involved its numerical status, the effect it was having on livestock and deer, and the effect hunting was having on it. Other states addressed these same ques-tions more or less about that time. As a result of these studies, few people are now worried about the immediate extinction of the puma in the western United States, and we have pretty much defined the circumstances under which they become troublesome with livestock. While these issues still exist, they are no longer the ones that make news. We still struggle over

appropriate regulations for hunting the puma, but these seem to be centered more upon ethics and politics than upon the long-termed welfare of the species. What seems to have most of our attention is the continued move-ment of humans into puma habitat and the resultant conflicts between the two species, including rare but frightening attacks on humans and, conversely, the ongoing loss and fragmentation of habitat. Added to this is the reap-pearance of the species in historic ranges to the East, which has created fear, concern over livestock loss, and conflicts regarding recommended puma hunting in these re-expansion areas. Do we have the knowledge we need to address the new problems that are arising? If so, how do we imple-ment that information, and to take up my California friend’s question, why should we? Can’t we just continue to apply our old tools of control and/or regulated hunting, and leave the rest to nature or fate?

I am convinced that my friend was intentionally, perhaps a little facetiously, presenting a pretty com-mon point of view in wildlife man-agement ranks. Our profession and

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 26

The following article was derived from a speech delivered by the author at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science on April 18, 2006. The forum was a panel discussion involving biologists, ranchers, environmentalists, and resource managers entitled “Sharing a Home with Predators: How Well do Humans and Mountain Lions Co-exist in Colorado?”

much of the public that supports it are by nature conservative. We do not change our mores easily or implement new knowledge quickly. This isn’t necessarily bad. Certainly any appar-ent, new knowledge requires some seasoning and testing before it can be trusted. Nonetheless, we do our best to convince all stakeholders involved in puma management that our judg-ments are based upon “good science,” with the unstated implication that by using “good science,” we use the latest knowledge to make ethically sound decisions.

But, while “good science” must have its own ethical basis, in that it purportedly seeks objective truth, sci-ence alone cannot determine human values. Ethical behavior, like beauty, is to some extent in the eye of the beholder. My favorite example here is a ranch manager I worked closely with during the early Spider Ranch puma study. He was elated when we confirmed a large number of calves in the puma diet and felt that this would end once and for all any con-flict over the species. If pumas ate beef, they should be eliminated – a simple conclusion deriving from the value system he espoused. Of course others, with other values, drew other conclusions from exactly the same set of data. Those wanting to protect the puma or those opposed to grazing on public lands saw it as proof that cattle shouldn’t be raised in puma country. While the study laid to rest the ques-tion of effects of pumas on cattle on some Arizona ranges, it didn’t modify many people’s values. It merely shifted the focus of the arguments. I’m not taking sides here, I just want to emphasize that facts alone do not necessarily change people’s goals.

As a young research biologist, I naively assumed that the science-

based facts I was obviously destined to discover would be welcomed by those in power, and that I’d receive their unending thanks and appropri-ate compensation for my contribu-tions. I hoped to improve species management and, of course, eliminate conflict. Slowly, however, I came to realize:

1. New knowledge isn’t always that easy to come by. Much of what we do in wildlife research centers on quantifying what we already knew qualitatively from years of experience.

2. Should you come up with something new, not everyone will accept your information, no matter how good your science.

3. Even when findings are com-pelling, the power hierarchy is just as likely to resist or ignore them as they are to thankfully apply them.

4. Scientific knowledge by its nature does not always simplify decisions or resolve conflict, and what you learn does not automati-cally benefit a species.

The truth of this latter statement, in fact, can make science rather un-popular. Dr. Daniel Sarewitz, Director of the Consortium for Science, Policy, and Outcomes at Arizona State Uni-versity recently wrote in American Scientist:

“The idea that a set of scientific facts can reconcile political differenc-es and point the way toward a rational solution is fundamentally flawed. The reality is that when political contro-versy exists, the scientific enterprise is ideally suited to exacerbating dis-agreement, rather than resolving it.”

To me, coming from one of our most prestigious general science journals, that’s a rather discouraging statement!

Dr. Sarewitz further notes that sci-ence can have its own biases:

1. For every value, there is often a legitimate supporting set of scientific results. That is, if you look hard enough, you can usually find a set of data to support your preconceived notions.

2. Specific scientific disciplines often turn out to be especially compatible with particular inter-ests and values. This can be exac-erbated by a tendency for agencies supporting research to ask only safe questions. One of my earli-est disillusionments as a young biologist occurred when a supervi-sor rejected a study proposal, quite honestly stating, with a shrug, that the agency might not want to have to deal with the findings, should they go the wrong way.

3. Science rarely provides sim-plistic or uniform answers but more often reveals the complexity in natural systems and our uncer-tainty in our knowledge of them. The cliché oft heard here is that the longer one works with a spe-cies, the less they know for sure.

Dr. Sarewitz suggests: ”…the most proper role for science in support of decision making comes only after values are clarified through political debate and after goals for the future are agreed upon through democratic means.”

At a seminar similar to this last year in Prescott, Arizona, I heard a research biologist from the Arizona

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 27

Game and Fish Department say this differently to a very large and politi-cally diverse group of people: “…we are scientists. We have knowledge of species, but you, the public, have to tell us what you want. We can only use our knowledge to carry out your goals.”

With all due respect to my Cali-fornia friend, Dr. Sarewitz, and to my fellow biologist, I disagree. In a world as polarized and complex as the one in which we live, that is changing as fast as it is, we cannot simply use science as a tool to carry out the goals of whatever regime happens to be in power. Certainly, ample examples ex-ist in history of misuse, even evil use, of science and technology. Scientists must constantly attempt to inform the public and, especially, decision makers, about what the ramifications of their decisions will be, while the values are being established.

I would venture that hope of relying on the democratic process to establish wildlife-related values is rather naive. First, in our money-driven world, defining our goals for the future is rarely determined through simple democratic means. Further-more, where the welfare of wildlife is concerned, the public at large has neither the time nor the ability to sort through the amount of information (but not necessarily truth) that flows from the Internet, television, newspa-pers, popular magazines, books, and so forth. Please don’t think I’m being arrogant in saying this. Take me away from my narrow area of expertise, and ask me to clearly understand the issues surrounding foreign policy or, for that matter, conflicts over some other environmental issue, and I’m as uncertain as the next guy. It becomes very easy to cling to old issues, old facts, old values, old ethics, and hope

the new ones will go away. A mentor once told me that

those of us who do wildlife research shouldn’t expect to see our results used in our lifetime. “Research re-sults are for the next generation,” is the way he put it. This was back in the 1960s, when things still seemed pretty simple. The speaker was a sec-ond-generation wildlife biologist with a much longer perspective than mine, and for many years I comfortably ac-cepted his philosophy, worrying little if no one paid attention to my work. Nonetheless, I have come to ques-tion this maxim. We now deal with a highly polarized public that often pressures wildlife agencies to carry out programs and to react to issues in ways that are not necessarily in keep-ing with their best knowledge about a species. Perhaps our most important role as scientists lies in emphasizing that the species we manage, the puma included, have very real, evolved, biological characteristics that con-strain what our management efforts can accomplish. These may not be discrete, absolute numbers, such as we find in the physical sciences (Hydro-gen atoms always have one electron; pumas do not always have a litter of exactly three young. The sun rises and sets on a 24-hour cycle. Pumas do not always hunt at night or always have a litter exactly every 24 months. Our Earth circles the sun with a closely predictable orbit. Female pu-mas do not always have a home range of 37.33 miles, or whatever average some particular study might find.), but they do operate within biologi-cal limits upon variations that we are beginning to understand, and manage-ment programs that do not recognize these natural limits are destined, if not to fail, at least to be wasteful of funds and personnel.

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 28

Our second important task is to emphasize that within the larger range of variation, the host of other traits affecting species and their manage-ment vary both geographically and even temporally within areas. Prey density, weather, and disease are in themselves variables that ultimately affect the behavior and survival of pumas during any given period. You can’t have one-size-fits-all, never changing, programs. In managing wildlife populations, including those of pumas and their prey, we are there-fore dealing with extremely complex, perhaps chaotic systems that do not necessarily react in a predictable, linear fashion to our anthropogenic nudgings. And effects of decisions we make now may radiate unpredict-ably far into the future. Considering that puma management invariably is driven by the interaction of a host of fairly narrow and immediate mo-tives – protecting livestock, protecting game animals, protecting human life, protecting puma populations, anxiety over human treatment of individual animals, or, too often, just winning a political battle – the hope that we might be able to manage wisely and objectively becomes tenuous at best. We need to monitor closely the results of our decisions.

It is another cliché among re-searchers that studies of populations are never long enough. The typical research project lasts only one to three years. A few have gone 10 to 15. They are invariably limited in geo-graphic scope by economic, person-nel, and political constraints. We start a study, usually rather spontaneously, when funds are allocated because some political flap focuses attention on the species. The very fact that a project is issue-driven means that it is probably being started after the prob-

Wild Cat News - www.cougarnet.org 29

lem can be easily solved – that we are already behind the curve. A good example of this is my own work on the North Kaibab, where we executed a three-year study to assess the impact of the puma on that famous deer popu-lation after the population had been declining for nine years. We found pumas present. We even watched the puma population crash. But we were too late to understand why the deer population had gone into decline nine years earlier. And we pulled out be-fore the population began to increase. You can interpret our three years of data just about any way you want to. Too often in such studies, even though focused on some single issue, the information provided will be all that is available for a state or a region, and is therefore in danger of becoming widely applied gospel, simply because no other information exists. But there are no guarantees that the information fits another place or even future condi-tions in the same place, so we must be extremely careful how we apply popu-lation and ecological research. Again, this isn’t physical sciences.

Our Cougar Management Guide-lines emphasized the need for “adap-tive management,” which is simply a modern buzzword for trying some-thing, watching closely what happens, and adjusting your management to improve results. Some would simply call this common sense. However, if we delve into the history of wildlife management, we find that very few management programs have been adequately evaluated and that once established, whether good, bad, or in-different, they can persist for decades. Even in the face of the increasingly advanced research technology, puma management involves a relatively lim-ited repertoire of tools, and manage-ment programs, whether in the form

of direct control, sport hunting strate-gies, or increased species protection, are rarely adequately monitored for their effectiveness, much less tweaked for improvement.

This is not necessarily the fault of the agencies. For much of what they do, good methodology does not exist for monitoring the outcome. On the whole, with their polarized pub-lic, they are under siege and may be forced into making decisions that have little to do with available biological information. Personally, I believe that we have studied puma popula-tions over a wide enough array of conditions to understand the range of their basic biological traits. We also know that our ability to predict fac-tors affecting wildlife populations and their trends is extremely limited. We desperately need better methods of monitoring conditions on a year-to-year basis and to bring our knowledge of the basic biology of the species to bear on predictive models.

However, wildlife managers can-not be expected to apply the intensive and usually expensive methods used in research. Pumas are only one of many creatures with which they have to deal. What they need are methods that can be applied fairly quickly. Even more, they need to be able to interpret the results of these methods in terms of what our now long pe-riod of research and field experience with cougars has taught us. Frankly, I don’t believe that we can do this through the traditional avenues of technical in-house reports or journal articles. As specialists with special experience and knowledge, we must take our knowledge directly to the field biologists and to the decision makers, and ultimately to the public, whether they ask for it or not. Those of us who produced the Cougar

Management Guidelines offered them as a beginning for such a process of evaluating and implementing new knowledge. We don’t expect them to perform miracles or to necessar-ily change stakeholder values, but we hope they serve to dispel myths and constrain puma management practices within the realm of practicality.

Wild Cat News© 2006 The Cougar Network: Using Science to Understand Cougar Ecology

The Cougar Network is a nonprofit research organization dedicated to studying the relationships of wild cats and their habitats. We are especially interested in wild cat populations expanding into new or former habitats. For more information, visit www.cougarnet.org.

By joining the Cougar Network, you will support our wild cat research and educational efforts. For your $30 annual membership, you will receive:

Want to become a member of the Cougar Network or make a donation?

• A subscription to our tri-annual publication “Wild Cat News,” featuring in-depth articles on North American carnivores.

• Frequent “Breaking News” e-mail alerts to keep you in the loop on exciting developments as they occur.

• Invitations to Cougar Network speaking events in your area.

• Discounts on merchandise sold in our online store.

• Satisfaction in knowing your contributions will be used to support the rigorous, peer reviewed science necessary to insure the continued recovery and long term conservation of North America's most charismatic carnivores. © 2006 The Cougar Network:

Using Science to Understand Cougar Ecology

The Cougar Network’s tri-annual publication dedicated to the scientific research of North American wild cats

Wild Cat NewsVol. 2, Issue 1. April 2006.

IN THIS ISSUEPotential Jaguar Habitat in Arizona

The Eastern Lynx

Mountain Lions in North Dakota

Lynx in Washington

Cougar Ecology and Management in Wyoming

Burmese Python Consumes Bobcat

VISA MC AMEX DISCOVER

Name on Card:Credit Card No.:Exp. Date: Amount:Billing Address:Signature:

Note: The Cougar Network will not share any of this confidential information with other organizations.

PLEASE DETACH AND MAIL TO: Ken MillerDirector & TreasurerCougar Network, Inc.75 White AvenueConcord, MA 01742

Please enclose a check payable to The Cougar Network, or provide your credit card information below:

To join or donate, visit www.cougarnet.org/members.html, or fill out and mail the information below.