Viroconium, an eariier foundation at Much Wenlock Abbey ...€¦ · Just seven miles from...

Transcript of Viroconium, an eariier foundation at Much Wenlock Abbey ...€¦ · Just seven miles from...

Just seven miles fromViroconium, an eariierfoundation at MuchWenlock Abbey may haveguarded the heirloomtreasures ot King Arthur andthe iineage of British kings.

Y THE SIDE of a Shropshire country lane a few miles east

of Salisbury, a deep trench reveals the stumps of classi-

cal columns—all that remains of the marketplace of the

Roman city of Viroconium, now called Wroxeter. Like

other such Roman towns, Viroconium had little protection from

attack; it lay across a major road intersection, by a navigable river

and surrounded by broad plains. And, like a number of other

towns, Viroconium sat in the shadow of a massively fortified hill

fort. The Wrekin, that had been abandoned in its favor. So it is

strange that this Roman city would survive after Roman civiliza-

tion collapsed in Britain during the 5th century, a period when

other major centers were abandoned.

Astonishingly, Viroconium not only survived the beginning of

the Dark Ages, it grew. Somebody added grand new buildings,

classically styled, in the center of Viroconium.

That somebody could have been King Arthur.

_ ArthurSlept Here!

Story and photos by Jim Hargan

MAY 2008 BRITISH HERITAGE

THE MODERN VERSION of King Arthur—Round Tabie,knights in armor and all that—starts with a baldly propa-gandistic pseudo-history penned by a Welshman namedGeoffrey of Monmouth in 1135. Titled The History of theKings of the Britons, it purported to describe all the CelticBriton kings going back a millennium before Christ, ingreat detail, and without a gap in chronology. Of these,Geoffrey gave pride of place to King Arthur, whom heplaced around AD 500; according to Geoffrey, it was Arthurwho expelled the Anglo-Saxon invaders. Geoffrey had twogoals in assembling what was, even in his day, dismissed asa farrago of nonsense and lies: first, toglorify the Welsh over their enemies,the English; and second, to suck up tothe Norman aristocracy that ruledEngland. "We have two things incommon," he was telling his Normanmasters, "a glorious history and ahatred of the despicable English." Itworked; the Normans made Geoffreya bishop.

SERIOUS HISTORIANS of the 12th cen-

tury condemned Geoffrey loudly andat great length, to no avail. Geoffrey'sstories, and particularly his accountof Arthur, were too lively. Geoffrey'sfake history became a medieval best-seller and touched off a host of imita-tors. These imitations and elabora-tions introduced a wealth of newconcepts, including the Round Table,Lancelot and Camelot. By 1284, KingEdward 1 had expropriated Anhur forrhe English and was using Arthur leg-ends against the Welsh, as a symbol of Britain reunited bya single King—namely Edward, who had just conqueredWales. Two centuries after Edward I, Sir Thomas Malorycompiled all of this material into the definitive modernchronicle, Le Morte d'Arthur.

Because Geoffrey's Arthur was so obviously medieval,and his "history" so much balderdash, historians simplyrejected Arthur's historicity out of hand for many years.Yet Geoffrey did draw on actual Dark Ages sources to addcorroborative detail to his propaganda. Historians nowagree that there is ample evidence that there really was aman named Arthur who lived around the year 500, andwho participated in the defeat of the Anglo-Saxon invadersand establishment of a British Celtic dominance that wouldlast until 550.

Experts still disagree on whether Arthur was the leaderof the British or just some local hero whose grossly dis-torted legends were picked up by Geoffrey. In 1992, how-ever, two British journalists proposed that a set of detailed

T HERE IS

AMPLE

EVIDENCE THAT

THERE REALLY

WAS A MAN

NAMED ARTHUR

WHO LIVED

AROUND THE

YEAR 500

conclusions about the real Arthur could be teased from thescant fragments of Dark Ages evidence. In their book KingArthur: The True Story, Graham Phillips and Martin Keat-man put forth evidence that Arthur could be identified asa real person who lived and ruled in Shropshire, and whodied in 519.

It's a fascinating tale. Phillips and Keatman first go overthe elements of the medieval ,\rthur tales that we know andlove, showing how all of them, including the oldest surviv-ing Welsh legends, were heavily influenced by Geoffrey'sself-aggrandizing tall tales. Then they review all the known

sources of Dark Ages history, show-ing how scholars have been able tobuild a fairly coherent account of thedarkest of those days, from 410 to570—an account that definitely in-cludes a historic Arthur. Finally, theyshow how tiny bits of neglected ev-idence allow Arthur to be placed asa specific ruler of a specific place.

You can visit the places in Shrop-shire where, they claim, Arthur lived,met Guinevere, stored his treasureand where Modred killed him. Thisis very controversial; Phillips andKeatman are not academic histori-ans, and lack the extensive knowl-edge of ancient manuscripts, archae-ology and the philology that makeDark Ages studies a minefield. Yet,unlike other such amateur Arthuri-ans, their overall story hangs to-gether and could well be true.

Here's the part of Phillips andKeatman's story that historians gen-

erally accept. By the year 400, the Celtic British had expe-rienced 350 years of prosperity as the Roman diocese ofBritannia, a land so peaceful that stone-built cities, filledwith riches, stood almost unprotected on open plains linkedby high-speed roads. Then things fell apart. Barbarians at-tacked everywhere, most definitely including Britannia, andthe Roman government cast off Britannia so as to concen-trate on more important places. Britannia's 19 civitates(tribal provinces) had to look to their own defense, appoint-ing an imperator (more of a commander-in-chief than anemperor) to replace their Roman governor. This worked atfirst, and the British maintained their Romanized lifestyleand economy for another 40 years.

In 425 an exceptionally capable and rich nobleman whocalled himself Vortigern (Celtic for "Overlord") took overas imperator. Vortigern defeated invaders from Ireland andScotland—but to do this, he hired mercenaries from thenorth German lowlands, the Saxons. Then, as a unifiedBritain enjoyed a decade of peace, Vortigern faced rebel-

36 • BRITISH HERITAGE MAY 2008

lious nobles, and he retained control by expanding hisSaxon forces. In 449 Vortigern made the fatal mistake ofentering an alliance with an ambitious Saxon commandernamed Hengist, and giving him the Isle of Thanet on thenortheast corner of mod-ern Kent. Hengist invitedhis countrymen to join himand thousands responded,with Saxons taking overKent and their cousins theAngles taking over Nor-folk. The Anglo-Saxons re-belled against Vortigern in455, overrunning Britan-nia in a disaster that per-manently destroyed whatwas left of Roman societyand economy.

Now THF STAGE WAS SCT forArthur. Vortigern disap-peared around 459, and anobleman named Ambro-sius Aureiianus—said tobe Vortigern's greatestenemy—took over. Tlie fol-lowing generations wouldhail Anibrosius as theiroutstanding bero, theirsavior and the founder ofthe nation that wouldIx-come the Cymry (in Eng*lish, the Welsh). It was along war, with battlesfought all over the island.Ambrosius exterminatedthe English in Sussex;his commander Artorius _

(Arthur) led another armynorth to retake strategically important Lincolnshire. Then,while Arthur subdued rebellious Britons in the Welsh bor-derlands, Ambrosius led devastating attacks into Essex.

By 488 Ambrosius was gone, and Arthur commandedthe British forces in their final, decisive victory at MonsBadonicus, in the Wiltshire Downs, in 493. Arthur died 26years later, in 519, fighting against "Medraut" (Ceoffreycalled him "Modred") at a place called Camlann. At thatpoint the unified Britain divided up into petty kingshipsand continuous civil war—a process described in 545 ingreat detail by a Shropshire-area priest named Gildas,whose jeremiad on the subject survives intact. In 550 theEnglish broke out of their enclaves to begin centuries ofconquest and the creation of England.

So much can be gleaned from the tatters of evidence that

Al Wroxeter Roman Cily. the hypocausts remain Ihal prauided

under-floor central heating to Ihe villas and public buildings

of the fourth largest town in Roman Britain.

survive from the Dark Ages. Phillips and Keatman believethey can extend this story, however, extracting importantpoints from obscure comers: a genealogy on an 8th-centurystone, now lost; stray statements in an 8th-century manu-

script that may have anolder source; unusual ar-chaeological findings fromWroxeter; and a difficultline in Gildas' 545 sermon.From this, they nurse outthe lact that Arthur was aShropshire lad.

Of course, Shropshiredidn't exist in .\0 500 anymore than did armoredknights or castles; it wascreated 280 years laterwhen an English king con-quered it, and it didn'tbecome a shire for another200 years, in 500 it waspart of the civitas of theCornovii, a province thatencompassed the richnorthern half of the SevernValley. In late Roman timesthe district to its west (nowin Wales) was a militaryzone, but by 500 theRoman military was longgone; the district hadgained the name of Powys,and was under the samerule as the Cornovii civitas.

And then there is theodd matter of Viroconium(Wroxeter), the capital of

_^_^^^^^^^_^_^__^____ the Cornovii. Gildas statesthat, after the Saxon break-

out a century before, all the capitals of the civitates wereput to the torch, their stones cast down and "covered witha purple crust of clotted blood, as in some fantastic wine-press." Archeology bears this out everywhere—exceptViroconium. Alone of the 19 capitals, Viroconium not onlywas untorched, it was also untouched. Even stranger, itexpanded.

Archeologists have shown that, while Viroconium con-tracted in the 300s, starting in the 42Qs a British king begana grand building program of large new structures in theRoman style, using post-and-beam timber construction.Phillips and Keatman argue that this was, indeed, Vortigern,just as later generations believed. It would explain why,alone of the civitates, archaeologists have found no evidenceof a contingent of Vortigern's Saxons "guarding" it, and

MAY 2008 BRITISH HERITAGE • 37

later sacking it. And it would explain where this local kinggot all his wealth, and felt so secure that he could live in anunprotected capital. Twenty years of being Britain's imper-ator would leave Vortigern very rich and very strong.

Today, English Heritage, the country's department ofantiquities, preserves the exposed remains of Viroconium,set out as they would have appeared in the high Romanperiod when it was thefourth largest settlement

in Britannia. The country - .lane running through itwas one of Roman Bri-tannia's most prominentsuperhighways, WatlingStreet, linking Londiniumwith the major settle-ments of the west; andthis intersects just outsidethe city with a major fordover the Severn. To oneside is the row of columnstumps, which is all thatremains above ground ofthe forum, the town'stnarketplacc and politicalcenter. On the other sideis the baths, a giant com-plex centered on a vastbasilica, built as an exer-cise hall, the size of acathedral.

One wall of the basilicahas remained exposed,above ground, for 15 cen-turies, and continues toloom over the site. It's animpressive site, the moreso as you walk slowly

Known as the "Old Werke," Ihe ancient brick wall of the Romanbasilica has stood looming over Viroconium. now WroxeterRoman City, since before tbe days of King Arthur.

(and that's exactly what a Dark Ages source calls him).Arthur's successor, described at length by Gildas, did stylehimself king, but by that time all tbat Roman stuff wouldhave seemed quaintly anachronistic. Arthur of theCornovii was likely the last Roman in Britain.

ARTHUR SKEPTICS BASH THEIR TMEORIF.S on the fact that

Gildas never mentionedArthur by name (whichwould have been "Arto-rius" in Gildas' Latin), butthat assumes that Arthurwas a Celticization of Ar-torius. Phillips and Keat-man propose the opposite,that Arthur took his namefrom the Celtic word"arth," for bear—andGildas does mention a ruleras The Bear, whose succes-sor gets a Gildas sneer as"coach driver for TheBear." The Bear and his un-worthy heir seem to haveruled from Viroconium.

The Shropshire link is akey that unlocks manydoors. One such door con-cerns the stone circleknown as Mitchell's Fold,one of only two in Shrop-shire; it seems that theISth-century antiquarianWilliam Stuckley not onlysurveyed this circle, but re-ported that the localsclaimed it was the placewhere Arthur drew the

around it, learning about the huge baths that made life alittle better for the Romans living in this cold and wet land.

Phillips and Keatman construct an elaborate chain ofevidence linking Vortigern's capital of 425 with Arthur'sseat of 49.5—but we can do it more simply. Vortigern, whoabandoned his Roman name for a Celtic one, was an earlyleader of the faction that wanted to throw off Roman cul-ture and government; Ambrosius Aureiianus, his enemy,led the faction wanting to preserve a Roman Britain. WhenAmbrosius took over in 460 he would have naturallyawarded his enemy's lands to his chief lieutenant, Arthur.And, as Ambrosius and Arthur considered themselvesRomans, Arthur would have needed neither dynastic jus-tification nor the title of rex (king) of the Cornovii; Arthurwould have probably styled himself <iH;c, militarv leader

sword from the stone. Ancient Welsh rulers had swords, notcrowns, as their symbols of authority, and these were pre-sented by tribal eldersatsitesof great antiquity and power.Mitchell's Fold would have been two millennia old by thetime Arthur was presented his sword, and historians tell usit would have looked very much as it does now, 15 cen-turies later. It's a beautiful site, with wide views, a fit placeto declare a great ruler.

Guinevere, too, might have been a Shropshire lass. Theimpressive hillfort at Oswestry, in Shropshire near theWelsh border, is known in Welsh as Caer Ogyrfan, namedfor Gogyfan, by tradition the father of Ganhumara—rendered by the medieval French poets as Guinevere. Thismakes political sense; Arthur would have wanted to bindthe family that controlled access to Powvs in close alliance.

36 • BRITISH HERITAGE MAV 2008

Most impressive is the Shropshire link to Arthur's lastbattle, given in the only undisputed contemporaneous ref-erence to him, a snippet in a chronology that reads, "Thestrife of Camlann in which Arthur and Medraut fell."Camlann is traditionally given as in Cornwall—a bit mys-terious, as Cornwall would have been far out of the main-stream of British politics and warfare, and ruled by abranch of the Cornovii nobility to boot. However, theRiver Camlad runs through southwest Shropshire, creat-ing a gap through the rough mountains of the WelshMarches that leads to Viroconium.

Modern maps show earthworks along the Camlad atthe traditional ford of Shiregrove Bridge, although veryrecent farming seems to have plowed them out. Arthurmay well have fallen right here, defending his demesnefrom invaders.

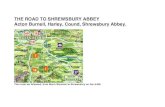

Local legend plays its part. Much Wenlock Abbey, insoutheast Shropshire, is reputed to be the place where thekings of Britain stored their treasure. Today's picturesque

ruins date only from1200, but they occupy amuch older site. Theabbey was founded byan English king shortlyafter he managed toannex this corner ofBritain in 680. Thetiming suggests a politi-cal act as well as a reli-gious one, perhaps as-serting English controlover a site important tothe Welsh. Located onlyseven miles from Viro-conium, perhaps an ear-lier religious foundationsafeguarded the heir-looms of the kingswhose line includedArthur, much as, 700years later, WestminsterAbbey guarded the

E NGLISH

HERITAGE

PRESERVES THE

REMAINS OF

ViROGONIUM

AS THEY WOULD

HAVE APPEARED

IN THE HIGH

ROMAN PERIOD

treasures of the English kings.These bits of history would have been preserved in the

kingdom of Powys, where the heirs of Arthur were natu-rally concerned more about local doings than events faraway. But Powys became separated from Shropshire in 780,forever as it turned out; and the stories of Arthur wouldbecome more remote, less meaningful and more fantasticas the centuries rolled on.

Still, when you look at that row of column stumps besidea country lane in Shropshire, you can't help but think,"What if King Arthur bad slept here?" " ^

WHAT IS THE DARK AGE EVIDENCE?

The stone circle known as Mitchell's F o i l one ol only two such henges

in Shropshire, was two millennia old when Arthur was declared king.

DARK AGE EVIDENCE is a Rubik's Cube; there are only so many tacts, and allyou can do is snap them together in difterent patterns. Just snapping thesquares together isn't enough, however, as not all the squares are equal.Here we can distinguish three periods of evidence. Contemporaneous ornear-contemporaneous evidence was first written while Arthur was alive, orwithin a generation ot his death, say from AD 450 to 570- As it so happens,there is nearly nothing of this sort ot evidence beyond Gildas' lengthy sermonof 545, De Excidio Britanniae (On the Ruin ot Britain).

Then there are the documents that can be traced within a handful ot cen-turies ot Arthur By 600 everyone who as an adult had ever known Arthurwas dead, and legends were already multiplying. To consider a documentto be historical evidence it has to be traced back further than this; otherwise,it merely shows what stories people were telling about Arthur, evidence ofan Arthur legend instead of a man. f\̂ any scholars maintain that this can bedone tor certain passages in a 9th century source known as the HistoriaBrit-lonum, a collection of works sometimes referred by its purported collector,Nennius, Some lines furnish internal evidence of great age, including achronology that mentions Arthur by name twice, a list of 12 of Arthur's bat-tles, and an aside that slates that Arthur was a dux rather than a rex.

Place names work the same as documents; 11 you can't trace an Arthurianplace name back to the 6th century, all it proves is what legends were pop-ular at that place at a later time. Genealogies, on the other hand, are neverreliable; they were compiled by kings who felt a need to prove their legiti-macy, and are nearly always partially or wholly taked. Genealogies, like ieg-ends, show what people believed in the 9th century, not what happenedduring the 6th century.

When you judge writings about Arthur it's important to be on the lookoutfor arguments that violate these criteria. For instance, an Arthurian can'tprove that there were two Vortigerns (father and son) merely by citing thefact that the Historia has Vortigem dying twice; if he can't show that bothreferences date to the 5th century, ail he's done is to describe the facf thatthere were two different 9th-century legends about Vortigern. Similarly, anArthurian can't claim that the name of the Welsh hillfort Dinas Emrys (Am-brosius' Fort) proves that Ambrosius was Welsh; without a 5th-century der-ivation, all it proves is that the Welsh admired Ambrosius. Finally, be skep-tical of any Arthurian argument using genealogies to give names to historiccharacters centuries past, Phillips and Keatman are big otfenders here, usinga 9th-century genealogy to give Arthur the name "Owain Ddantgvi/yn"—aname that just as easily could have been made up to fill a gap.

J .H .

MAY 2008 BRITISH HERITAGE • 59