Vikings, lecture 3

-

Upload

kristian-pedersen -

Category

Documents

-

view

162 -

download

0

Transcript of Vikings, lecture 3

The Vikings at Home

Social Structure and Political Institutions of the Scandinavian Communities

Social Structure In this lecture, we shall look at the

social structure of Scandinavia in the first half of the Viking Age (AD 700 – AD 900)

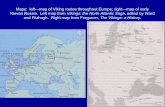

This shall also encompass an overview of relations amongst the regions and peoples of Scandinavia and their immediate neighbours to the south, east and west

Let us consider the most fundamental aspects of the social structure in Scandinavia: sex and labour divisions, patterns in land ownership, craft specialisation, and hierarchical organisation

It remains to be demonstrated that these patterns were shared across this vast region and evolved at the same rate

Sources

At the outset, it is worth enumerating the nature of the sources which provide us with an insight into social structure

At the risk of over-simplification, we can arrange the sources in the following broad categories:

1.Archaeological

2.Textual

3.Mythical

4.Literary Each of these affords only a partial

perspective and introduces a series of biases inherent to their basic premises

Archaeological Evidence The incompleteness and randomness of

the textual evidence, along with the many interpretive difficulties inherent in the mythical and literary sources, has compelled many to privilege the evidence deriving from archaeological investigations

This evidence is, however, also potentially problematic

Although the archaeological evidence may be regarded as 'objective', it has no meaning in itself and must be situated into an interpretive framework for it to acquire significance for understanding social relations

It would be incorrect and misleading to suggest that the archaeological evidence is not interpreted within a framework that is partly built on textual, mythical and literary sources

Inferences

Textual Evidence

A reasonable quantity of documents exist that describe Scandinavia and Scandinavians in the first phase of the Viking Age

Many of them were descriptions made by the clergy in their attempts to spread Christianity to the heathen lands

The political circumstances are outlined by Frankish sources as the nascent Danish kings came into conflict with Charlemagne and his descendants

Unflattering descriptions are also offered by Arabic sources

Problems of Interpretation

The principal problems that arise in using the textual sources describing Scandinavia and Scandinavians in the Viking Age are that they are culturally biased and incomplete

Biases arise from the attitudes of the chroniclers towards pagan societies, but also towards less urbane and sophisticated cultures

Sometimes the biases are introduced by the nature of their relations: the Frankish sources are content to merely describe the political circumstances that brought them into conflict with Scandinavians

The incompleteness is also a problem, as they are usually short and we know little of the places or people that they are describing in any detail

Mythical Sources

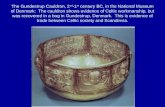

In some circles, particularly those of the French sociological schools that trace their descent from Émile Durkheim, it is suggested that the myths convey vital information concerning social organisation and the ideal relationships amongst social groups

As the pagan Scandinavian societies were illiterate, none of their practices nor their beliefs were recorded

We know of their religious life only through myths recorded in the Icelandic Sagas and the historical writings of the Scandinavian chroniclers from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries

It is therefore difficult to be certain of the authenticity of the beliefs and customs recorded in these sources

Populating the Scandinavian World

One of the more curious mythical accounts is the tenth century poem entitled Rígsþula ('The Song of Rig) which outlines the origin of three divinely ordained social classes: slaves or bondsmen, freemen, and rulers

In this myth, the deity Heimdall is identified as the father of all mankind

This account is partly at odds with other mythical traditions, but this should not reduce its value—the important aspect of this tale is the identification in broad terms of different social classes which must have appeared quite natural to those hearing the poem

Literary Sources The richness of the Icelandic Sagas has

tempted many generations of scholars to regard them as accurate accounts of the Viking Age

This assumption was comprehensively demolished by the Swedish scholars Curt Weibull and Lauritz Weibull and the Norwegian scholar Halvdan Koht in their studies

Many of the accounts were jettisoned as historical sources and seen instead as literary embellishments with no value for proper historiography

Nonetheless, even in these accounts there is the possibility of identifying recurring themes that might not reflect history in our strict use of the term, but instead represent the prevailing social structure

Sex and Age Distinctions

Identifying the Division of Labour Based on Sex and Age in the Viking Age

The Mortuary Evidence

In the reconstruction of social relationships and hierarchy, archaeologists privilege the mortuary record above all else

This is because it is assumed that the social status of an individual is reflected in the investment of labour lavished on the disposal of the corpse

The mortuary traditions of Scandinavia in the earlier Viking Age are, however, diverse and this may not correlate closely with status on every occasion

Some of the diversity is probably attributable to religious affiliation, whereas others may represent regionally favoured traditions if not aspects of life and death that we could not reconstruct from the archaeological evidence alone

Distinctions Based on Sex

The most fundamental social divisions are those based on sex and age

In the mortuary record of Scandinavia, however, there is little evidence of sexual distinctions

Graves and cremations of men and women are similar, and high status mortuary features such as the ship burials are not specific to any sex

The only differences in the graves and cremations are grave good, but only those of incidental significance: these are usually the result of men and women being buried in their clothes and jewellery and do not represent any deliberate inclusion or omission of any grave goods

Sexual Distinctions: Other Sources

But what do we know about the sexual distinctions obtaining in Scandinavian society from other sources ?

The textual, literary and mythical sources provide valuable insights into the social distinctions and division of labour between men and women in the Viking Age

As a rule, women in Scandinavian society enjoyed many rights and were largely the equals of men in most respects

Evidence corroborating this statement largely derives from the literary, textual and mythical sources

The Account of the Rus A description of the

Scandinavians along the Russian and Ukrainian rivers, known to the indigenous population as the Rus, was written by the Ibn Fadlan

He was sent by the Caliphate of Baghdad with an embassy to the King of the Bulgars on the middle stretches of the River Volga in AD 921

We shall return to this account in more detail, especially for its vivid description of burial rituals, but for the moment let us consider its statements concerning the status and treatment of women

Dress and Status The status of the women seems to be

largely dependent on the wealth of the husband: 'Each woman wears on either breast a box of iron, silver, copper or gold; the value of the box indicates the wealth of the husband'

Distribution of wealth at death is described thus: 'They burn him in this fashion: they leave him for the first ten days in a grave. His possessions they divide into three parts: one part for his daughters and wives'

This last statement suggests polygamy, but it is not encountered in any other sources

Perhaps Ibn Fadlan did not distinguish between a wife and a concubine, or that there were customs prevalent in the east that are not recorded elsewhere

Priestesses Ibn Fadlan then describes a priestess,

responsible for the sacrifice of the slave girl: 'Then came an old woman whom they call the Angel of Death, and she spread upon the couch the furnishings mentioned. It is she who has charge of the clothes making and arranging all things, and it is she who kills the girl slave. I saw that she was a strapping old woman, fat an louring'

This suggests (and there is no reason to doubt the account) that females were also responsible for the administration of religious rites

We have similar testimony from Tacitus and other classical writers, describing rites over which females officiated

Rulers and Aristocrats

It appears, from both the written and archaeological evidence, that women were full members of the aristocratic circles

The most salient example of this is afforded by the extraordinarily rich ship burial at Oseberg, in Norway

This contained the remains of a woman that oral tradition identifies as Queen Ása

Inside the mound was a skeleton of a woman, so this is consistent with the oral tradition

Most of all, though, it reveals that a woman's status was not governed exclusively by her sex but her family connexions and marriage

Oseberg Mound

Oseberg Carriage

Oseberg Tapestry

Status Distinctions

Social Hierarchy, Class Distinction and Political Structure

Bondsmen and Freemen Men and women could be free

(bondi and karls) or be slaves (thrall for males, ambett for females)

It is difficult to discriminate between freemen and bondsmen through the archaeological record

Many of the burials and cremations, for instance, were simple and lacked grave goods of any note

This was presumably identical for the lower levels of the freemen and bondsmen

It is nonetheless possible to associate different social classes with certain settlements and houses

Common Mortuary Traditions

Ladby, Fyn