ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSawsc.uonbi.ac.ke/sites/default/files/chss/arts/awsc/Food... · Web...

Transcript of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSawsc.uonbi.ac.ke/sites/default/files/chss/arts/awsc/Food... · Web...

AFRICAN WOMEN STUDIES CENTREUNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI

FOOD SECURITY FINAL REPORT

Implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) of the Kenya Constitution

FINAL REPORT

ZERO TOLERANCE TO HUNGER AND MALNUTRITION

Submitted to:FEB 2015.

African Women’s Studies Centre

University of Nairobi

P.O Box 30197- 00100

Tel: (+254-20) 318262 Ext: 28075; Mobile: (+254) 725 740 025

Email: [email protected]

Website: http://awsc.uonbi.ac.ke

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

___________________________________________________________________________

ACSU Agricultural Sector Coordinating Unit

ASAL Arid and Semi-Arid Lands

AWSC African Women’s Studies Centre

CTP Cash Transfer Programme

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GHI Global Health Index

GMO Genetically Modified Organisms

GoK Government of Kenya

HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

IDP Internally Displaced Persons

IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute

KNBS Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

MCI Members of County Assembly

MDG Millennium Development Goals

MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework

NCPB National Cereals and Produce Board

3

OVC Orphans and Vulnerable Children

PWD People with Disabilities

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

VAT Value Added Tax

WFP World Food Programme

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The successful implementation of this project has been made possible by the

support, encouragement and goodwill of many individuals from the University

of Nairobi and other institutions. While we cannot mention all the persons that

were involved in this process, we acknowledge the support of the Vice

Chancellor, Prof George Magoha, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor Administration &

Finance, Prof Peter Mbithi, the Principal of the College of Humanities and

Social Sciences, Prof. Enos Njeru and the Principal of the College of

Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, Prof. Agnes Mwang’ombe.

The African Women’s Studies Centre (AWSC) Standing Committee on Food

Security has led the way with great dedication, having put in a lot of time and

effort. The members of this Committee include: Prof. Tabitha Kiriti-Ng’ang’a,

School of Economics, Prof. Wanjiku Kabira, Director AWSC and Department of

Literature, Prof. Margaret Jesang Hutchinson, College of Agriculture and

Veterinary science, Dr. Gerrishon Ikiara, Institute of Development and

International Studies, Dr. Wanjiru Gichuhi, Population Studies Research

Institute and Dr. Mary Lucia Mbithi, School of Economics as well as Prof.

Elishiba Kimani, Gender and Development studies, Kenyatta University. The

AWSC is also grateful to the members of the University community and

representatives of civil society for their technical work, time and commitment

to this project.

5

Prof. Patricia Kameri- Mbote, Dean, School of Law UoN, Dr. Linda Musumba,

School of law Kenyatta University and Dr. Godfrey Musila, School of Law UoN

have been very vital in the development of the food security Bill 2014.

The Centre has had several partners in the different activities carried out

during the project period. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics has been

vital in the baseline survey. The team was lead by the very able Director

General, Mr. Zachary Mwangi. Mr. James Gatungu, Director of Production

statistics directorate, Ms. Mary Wanyonyi, Senior manager, food monitoring

and environment statistics and Patrick Mwaniki the senior manager

agriculture and livestock were very helpful and insightful during the entire

process. Great support was received from Mr. Josiah Kaara and Mr. Benard

Obasi as well as Mr. John Bore and Mr. John Mburu for their analysis and

sampling skills respectively.

The AWSC is thankful to the Women Enterprise fund, Maendeleo ya

Wanawake representatives, KNBS statistical officers, Area chiefs and village

guides from the 21 Counties for the mobilisation of respondents during the

research surveys.

The field surveys would not have been successful if it were not for the hard

work and commitment shown by the lead researchers and enumerators. The

full list of the research teams is appended.

Policy and intervention proposals emanated from the research and desk

study that was carried out during the implementation of this project. The

6

proposals were then shared with policy makers and parliamentarians. The

AWSC would like to appreciate the opportunities granted to share these

proposals with the Majority Chief whip of the senate, Senator Beatrice Elachi,

Chairperson Senator Lenny Kivuti and committee members of the Lands and

Natural resources committee of the Senate, Chairperson of the Legal and

Human right committee of the Senate, Senator Amos Wako, Chairperson of

the Agriculture committee of the Senate, Senator Kiraitu Murungi, Director of

the Senate Committee services, Mr, Njenga Njuguna, Chairperson of the

budget and appropriation committee of the National Assembly Hon. Mutava

Musyimi and Officials from the National Assembly, Mr. Paul Ng’etich and Mr.

Kepha Omoti.

The AWSC is very grateful to the Members of the 21 County Governments

and Assemblies where research was conducted. These include Nairobi,

Makueni, Kajiado, Mombasa, Bomet, Baringo, Kisumu, Migori, Kisii, Kwale,

Taita Taveta, Elgeyo Marakwet, Kirinyaga, Laikipia, Turkana, Isiolo, Kiambu,

Nakuru, Bungoma and Trans Nzoia. These County Governments and

Assemblies were very receptive to receiving the findings on food security in

their counties and receiving recommendation and proposals to ensure that no

person goes to sleep in their counties.

The AWSC Secretariat consistently carried out research and ground work for

the implementation of this project. They have played a pivotal role in the

writing and compilation of reports as well as organizing the various technical

meetings and consultations. Appreciation goes to Mr Gabriel Mbugua, Mr

7

Gideon Muendo, Mr Gideon Ruto, Mr. Gideon Waweru, Mr Isaac Kibet Kiptoo,

Mr Joseph Owino, Mr Kennedy Mwangi, Ms. Minneh Nyambura, Ms. Priscilla

Nekipasi, Mrs. Rosalyn Otieno, Ms. Veronica Waeni Nzioki, Ms Wanjiku

Gacheche and Mr Wellington Waithaka who are very committed to the

success of this project.

Kenyans expect and deserve the promise of Article 43 (1)(c) of the Bill of

Rights to be translated into reality. This is a worthwhile journey that the

Centre has embarked on and we intend to walk this path with others until the

day when no Kenyan goes to bed hungry!

Prof. Wanjiku Mukabi Kabira, EBS

Director, African Women’s Studies Centre

University of Nairobi

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The African Women’s Studies Centre (AWSC) is based at the University of

Nairobi. The Centre is informed by the recognition that the experiences of

African women in almost all spheres of life have been invisible. The Centre

therefore aims to bring women’s experiences, knowledge, needs and world

view to mainstream knowledge and processes. The Centre recognizes the

efforts made by the Government of Kenya towards implementation of food

security. However, given the poverty situation in the country and the food

security vulnerability, more needs to be done towards enhancement of an all-

inclusive countrywide food security policy and programming. The AWSC has

therefore chosen to focus on working with parliament, county assemblies,

national and county governments and other policy makers in order to ensure

the implementation of article 43 (1)(c) that guarantees Kenyans the right to

food. The Centre also plans to complement and support the implementation

of the Food Security and Nutrition Policy as well as other initiatives such as

the National Social Protection Policy, Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Authority

Act among other policy documents aimed at ensuring food and nutrition

security. The project also takes cognizance of the many provisions in the new

constitution that offer new system of government where decentralization and

people’s participation in policies and programmes is entrenched as well as

schedule four of the constitution that devolves some of the activities related

to food security to the county governments.

9

The research findings and recommendations presented here are a follow up

of AWSC presentation of best practices report and recommendation on the

implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) to the 10th parliament in 2012 during the

budget hearings. With this financial support from treasury through the

Ministry of Education and UoN (AWSC), put together a team of experts to

work on this research. The team of researchers included economist, experts

in the fields of agriculture, social scientists and legal experts. University of

Nairobi also developed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Kenya

National Bureau of Statistics to work on the household baseline survey on

food security. AWSC conducted the research in collaboration with KNBS

during the calendar year 2013. The research was carried out in the six agro-

ecological zones and in 20 counties namely: Kisii, Nairobi, Kiambu,

Nakuru, Elgeyo-Marakwet, Kirinyaga, Kajiado, Bomet, Makueni,

Bungoma, Taita Taveta, Migori, Trans Nzoia, Turkana, Baringo, Isiolo,

Kwale, Mombasa, Nandi, Laikipia.

The objectives of the research were to: establish the status of food security

in the Country; review best practices in institutional, legal and policy

frameworks for implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) and make policy

recommendations at the national and county levels; involve citizens’

participation in development of food security initiatives; use evidence based

advocacy for greater allocation of resources for food security initiatives;

establish whether the economic, social and political pillars of Vision 2030 take

into consideration food security concerns. In addition, the team was to

10

evaluate vision 2030 pillars using the research findings for their capacity to

ensure food security; share the research findings with the food security

stakeholders (policy makers, civil society organizations and the general

public) at the county and national levels; generate proposals for ensuring full

implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) of the Kenya Constitution 2010 and to

document women’s experiences, knowledge and perceptions in relation to

food security and share the findings.

The methodologies used by the researchers included a household survey

where 4,200 households in the 20 counties were interviewed on their food

security status using a hunger module that assessed experiences in the last

10 months. The issues addressed included: availability, access, utilisation and

sustainability. In addition to this household survey, views of opinion leaders

were sough through: key informant questionnaire, Focus Group Discussions

and debriefing sessions. Institutional questionnaire were administered to get

the opinions of government officials on food security in each of the counties

visited.

Initial research findings were shared with county governments, members of

the county assemblies and members of the CSOs for further input. Research

findings from the 20 counties and desk review on institutional, policy and

legal frameworks were shared at a national workshop with the chairpersons of

the agriculture committees of the county assemblies.

Among the key research findings is that on average 18 percent of Kenyans

are either often or always hungry as indicated in the table below. The table 11

shows that the worst hit county in terms of hunger is Turkana County (54%)

while Kirinyaga is the least affected (3%).

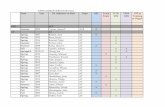

Table1: Hunger module- with average of E07 and E08

County Name

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household because there were not enough resources to go around?

(Often and Always)

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?

(Often and always)

Average

1 Turkana 59.5% 48.1% 54%2 Kisii 47.0% 35.5% 41%3 Migori 35.9% 31.8% 34%4 Isiolo 32.5% 25.5% 29%5 Kwale 24.8% 16.7% 21%

12

6 Mombasa 24.3% 16.1% 20%7 Nairobi 19.6% 20.1% 20%8 Trans

Nzoia22.0% 17.2% 20%

9 Makueni 21.0% 17.9% 19%1

0Nandi 23.7% 12.6% 18%

11

Baringo 18.9% 15.6% 17%

12

Bungoma 20.2% 12.7% 16%

13

Taita Taveta

15.7% 15.1% 15%

14

E. Marakwet

13.8% 11.0% 12%

15

Laikipia 17.2% 7.5% 12%

16

Kajiado 11.0% 5.3% 8%

17

Kiambu 8.4% 6.0% 7%

18

Nakuru 7.2% 4.5% 6%

19

Bomet 6.1% 3.6% 5%

20

Kirinyaga 3.1% 2.1% 3%

Average 21.0% 15.7% 18%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

The findings also show that the sources of livelihood for the respondents

in the 20 counties, is mainly: own production at 39.4percent, casual labour

(agriculture and non-agriculture related) 20.9 percent, regular monthly salary

16.9 percent, trade/small businesses 16 percent, sale of livestock 3.2 percent,

remittance from relatives 2.1 percent, while help from relatives and public

stood at 0.7 and 0.6 percent respectively. From the findings, it is important to

13

put emphasise on own production, employment as well as trade/small

businesses. Given these findings, we have made proposals on how to improve

food security in these three categories.

The research findings also show that a majority of the respondents have

nothing to store with 86.6% saying they have nothing perishable to store

while 51 percent said they have no non-perishable foods i.e. cereals and

pulses including beans, cow peas, maize, rice and rice, to store.

Some of the key policy and programme recommendations derived from the

participants and study findings include:

i. Family Support Programme

The study shows that at least 18% of the respondents are often or always

hungry. According to the Kenya National housing and Population Census of

2009 Kenyans numbered 38.4 million. The National Council for Population and

Development in their latest report on facts and figures (2012) puts the Kenya

population at 39.6 million and using this figure the number of those who are

often or always hungry in Kenya translates to 7.1 million. From this figure the

population.

It is clear from the findings that there is need to focus on the 18% and target

them directly and we propose the family support programme through the

national government through County governments should establish a family

support programme. Following the example of India and Brazil the Kenyan

government can directly focus on the households and ensure that they have

14

access to food through either increased production (40% who produce their

own food ), creation of employment for casual labourers (21%) and

opportunities for markets and trade (16% who engage in trade and small

business). The category of 7.1 million who are often and always had indicated

that this are their sources of their livelihood.

ii. Water for irrigation and domestic use

From our study, most of the respondents from the ASAL areas which included

Kwale, Isiolo, Elgeyo Marakwet, Laikipia, Taita Taveta, Makueni,

Kajiado, Turkana and Baringo proposed the introduction of or scaling up

of irrigation. The report proposes support for irrigation and water for domestic

use targeting the 18% of Kenyans who are always hungry.

iii. Economic Empowerment of youth and women

Enhancement of women enterprise fund, UWEZO fund and youth fund and

ensure targeting of 7.1 million Kenyans fir increased production and

enhancement of trade/small businesses.

iv. ICT and Business HUB

To foster sharing of information related to government activities that are

geared towards improving lives of women and youth as well as the general

public. This will support and promote digitization which will market youth and

women enterprise through advertising and sharing of available opportunities

as well as development of ICT products that will market goods and services.

v. Draft food security bill developed

15

A draft legislative framework that could enforce food security programmes

including family support programme, cash transfer and other initiatives aimed

at implementation of article 43 (1)(c) of the constitution has been developed

and submitted to the Senate for consideration. The following report covers

background and context to the research.

AWSC recognises the Kenya Government’s efforts to make the country a

food secure country. It has pursued achievement of food security at various

levels including at the global level by being a signatory to key global

declarations such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and at the

regional level including being a signatory to the Maputo Declaration. At the

national level, Kenya has been implementing programmes to improve the

level of income and contribute to food security. Key among these

programmes is the Economic Stimulus Programme and the Kenya Vision

2030. The National Food and Nutrition Security (FNSP) Policy, The Kenya

Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Authority (AFFA) Act are some of the national

efforts by the government to enable people access food and of accessible

quality. In spite of all these initiatives, Kenya remains largely a food insecure

country. AWSC intends to complement these government efforts as well as

initiate measures for food security in the country.

16

1.1 Introduction

The study on food security in Kenya by the AWSC and the KNBS is part of a

process to meaningfully engage and contribute to the current national

discourse on the implementation of the Constitution of Kenya (2010) Article

43 (1)(c), which states that “every person has a right to be free from hunger,

and to have adequate food and of acceptable quality” (Republic of Kenya,

2010).

Food security has remained one of the global issues today and efforts to

achieve it have remained a challenge for many countries, more so in Sub-

Saharan countries. Kenya has about 80 percent of its population residing in

the rural areas where agriculture dominates (National Food and Nutrition

Policy, Republic of Kenya, 2011). The 2010 Economic Review of Agriculture

indicates that 51 percent of the Kenyan population lack access to adequate

food. Food security is closely linked to poverty, which is estimated at 42%

nationally (Economic Review, World Bank, 2013). About a third of Kenya’s

population is considered food insecure. Currently over 10 million people in

Kenya suffer from chronic food insecurity and between two and four million

people require emergency food assistance at any given time (National Food

and Nutrition Policy, Republic of Kenya, 2011). Nearly 30 percent of Kenya’s

children are classified as undernourished, and micronutrient deficiencies are

widespread.

17

In October 2012, the Centre embarked on this research project in October

2012 with the field work being carried out between April and July 2013. This

field work took place in twenty one counties in the six agro-ecological zones

of Kenya.

The objectives of the research were:

i. To establish the status of food security in the Country.

ii. To document women’s experiences, knowledge and perception in

relation to food security and share the findings.

iii. To review best practices in institutional, legal and policy frameworks

in selected food secure countries for implementation of Article 43 (1)

(c).

iv. To generate and use data to advocate and lobby for more responsive

institutional, legal and policy frameworks as well as greater allocation

of resources for implementation of food security initiatives

v. To share the research findings with the food security stakeholders

(policy makers, civil society organizations and the general public) at

the county and national levels.-

vi. To generate and disseminate the findings to the various food security

stakeholders.

The outcomes of the project were:

i. Status report - Proposals on programmes and interventions at the

national and county levels developed.

18

ii. Women’s experiences, knowledge and perceptions with food security

documented and recommendations shared.

iii. Proposals on policy and institutional frameworks for food security

developed and shared with relevant ministries, parliament and vision

2030 secretariat.

iv. Draft legal framework for implementation of Article 43 (1)(c)

established and shared;

v. Budget proposals for 2014/15FY on food security shared with policy

makers.

vi. Proposals on food security proposals shared with County Governments

and other stakeholders.

vii. Awareness on food security programmes and interventions created

among the public.

viii. Proposals emanating from the public developed at county level shared

with policy makers, parliament and county governments.

1.2 Study Methodology

Secondary data on various cross-cutting indicators of food security/insecurity

was collected. Information of the country on geography and climate;

touching on rainfall and agro-ecological zones was sought. Information was

also obtained on population and related parameters like household size,

urbanization, birth and death rate, life expectancy, child and maternal

mortality, orphans and vulnerable children, and child nutrition. Economic

indicators like country’s gross domestic product (GDP), agriculture and

19

economy, poverty index, HIV and Aids prevalence, and unemployment, were

also examined. Data was also obtained on school enrolment, food

consumption and malnutrition. Government expenditure allocation to line

ministries in food security i.e. agriculture, livestock and fisheries as well as

social safety and equalization Fiscal Year 2012/2013 was examined.

Data on best practices from selected countries which have achieved food

security was also examined.

The country was classified into six Agro-Ecological zones and the Counties

visited were selected based on these Agro-ecological Zones: Upper

Highlands, Upper Midlands, Lowland Highlands, Lowland Midlands, Inland

Lowlands and Coastal Lowlands. Agro-ecological Zoning (AEZ) refers to the

division of an area of land into smaller units, which have similar

characteristics related to land suitability, potential production and

environmental impact (FAO 1996). Since more than 80 per cent of Kenyans

derive their livelihood from agriculture, classification of counties according to

potential agricultural production and land use with the exception “urban

counties” has a direct bearing on food security in those counties and in the

entire country. Nairobi and Mombasa counties were purposefully selected as

they consist of 100 percent urban population according to the Kenya

National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). The 20 counties sampled for the study

were; Kisii, Nairobi, Kiambu, Nakuru, Elgeyo-Marakwet, Kirinyaga,

Kajiado, Bomet, Makueni, Bungoma, Taita Taveta, Migori, Trans

Nzoia, Turkana, Baringo, Isiolo, Kwale, Mombasa, Nandi, Laikipia.20

The study methodologies included a household survey where in depth

interviews were conducted in 4,200 households in the 20 counties, Focus

Group Discussions, use of Key Informant Questionnaires to seek the opinion

of the leaders, Institutional Questionnaires to get the opinion of government

officials on food security and a debriefing meeting was held at each county

after the field work.

Initial research findings were shared with county governments, members of

the county assemblies and members of the CSOs for further input. Research

findings from the 20 counties and desk review n institutional, policy and legal

frameworks were shared at a national workshop with the chairpersons of the

agriculture committees of the county assemblies.

PART1: Food Security Household Baseline Survey.

Introduction

This section presents the results of the household baseline survey on food

security in Kenya. Food security exists when all people, at all times, have

physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food

21

that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy

life (FAO, 2001). Household food security means applying this concept to

individuals within the household. Conversely, food insecurity exists when

people do not have adequate physical, social or economic access to food

(FAO, 2001). Chronic hunger is also a sign of food insecurity and the hunger

module was used to determine the status of food security at the household

level in the twenty sampled counties. It assesses the status of food security at

the household level in the last ten months before the survey was conducted

in June 2013. The eight questions in the hunger module assess the four

dimensions of food security (availability, accessibility, utilization and

sustainability). Household heads were asked to rate the status of food

security in their households based on the eight questions. The hunger module

ranks the twenty counties from the least to the most food insecure based on

the average manifestation of food security findings derived from the

percentage of responses on each of the eight questions. A part from the

hunger module, food security was analyzed in terms of key determinants of

food security such as gender of the household head; marital status of the

household head; level education of the household head and household size.

Status of hunger

Table: Hunger module- with average of E07 and E08

County Name

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household because there were not enough resources to go around?

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?

Average

22

(Often and Always) (Often and always)

1 Turkana 59.5% 48.1% 54%2 Kisii 47.0% 35.5% 41%3 Migori 35.9% 31.8% 34%4 Isiolo 32.5% 25.5% 29%5 Kwale 24.8% 16.7% 21%6 Mombasa 24.3% 16.1% 20%7 Nairobi 19.6% 20.1% 20%8 Trans

Nzoia22.0% 17.2% 20%

9 Makueni 21.0% 17.9% 19%10 Nandi 23.7% 12.6% 18%11 Baringo 18.9% 15.6% 17%12 Bungoma 20.2% 12.7% 16%13 Taita

Taveta15.7% 15.1% 15%

14 E. Marakwet

13.8% 11.0% 12%

15 Laikipia 17.2% 7.5% 12%16 Kajiado 11.0% 5.3% 8%17 Kiambu 8.4% 6.0% 7%18 Nakuru 7.2% 4.5% 6%19 Bomet 6.1% 3.6% 5%20 Kirinyaga 3.1% 2.1% 3%

Average 21.0% 15.7% 18%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

Other research findings also reveal similar causes of food insecurity in

Kenya. According to Nzomoi (2008), many households are food insecure not

only because of agricultural commodity price increases, but also because of

other non-price determinants. Commodity price increases are mainly caused

by supply constraints due to output fluctuations. Output fluctuations are

influenced by a number of factors including erratic rainfall, poor quality

23

seeds, high cost of inputs especially fertilizer, poor producer prices as well as

pests and diseases. From the international scene, increase in the prices of

foodstuffs is also attributed to the ever-rising crude oil prices. Similarly, in the

local economy higher commodity prices are also blamed on high international

crude oil prices which translate to increased cost of production of the

commodities.

Food insecurity, one of the main problems facing Kenya, involves a great

number of factors such as poverty, high food price volatility, poor

infrastructure, underfunding of the agricultural sector, fragile political

stability, changing climatic conditions and dwindling natural resources

needed for the production of food. Also influencing food security is the

structure of agricultural production and a focus on growing export crops such

as tea and coffee, an area in which Kenya has concentrated due to its

comparative advantages in international trade. However, since the country

exports unprocessed agricultural commodities without value addition, the

profits from this type of trade are minimal for the small-scale food producers

(Prague Global Policy Institute, 2013).

In general, the research findings in the hunger module indicate that

Kirinyaga County is the least food insecure with an average manifestation of

food insecurity rated at 6.1 percent and Turkana County is the most food

insecure rated at 67.3 percent.

As already discussed, food insecurity in Kenya involves many factors such as

poverty, high food price volatility, underdeveloped infrastructure, 24

underfunding of the agricultural sector, changing climatic conditions and

declining natural resources required for food production. The top priority of

the Government therefore should be the implementation of the right to food

as stipulated in article 43 (1)(c) of the Constitution. In this case, the

Government should allocate more resources to the agricultural sector;

support the status of small-scale food producers (farmers and herdsmen

alike); encourage local rural agricultural associations; ensure a stable political

environment and introduce adaptation and alleviation measures in reaction to

climate change.

1.2 Hunger indicators by selected demographic characteristics

Table 3: Hunger Indicators by gender of the household head

Question Gender of Household Head

Never

Sometimes

Often

Always

% % % %

E01: Did you worry that your household would not have enough food?

Male Female

28.522.6

44.442.6

16.318.4

10.816.4

E02. Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of lack of resources?

Male Female

23.118.1

46.943.0

19.623.0

10.415.9

E03. Did you or any household member eat a limited variety of foods due to lack of choices in the market?

Male Female

40.235.5

37.838.0

14.315.9

7.710.6

E04. Did you or any household Male 24.0 46.8 19.6 9.6

25

member eat food that you preferred not to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food?

Female 18.8 45.3 21.9 14.0

E05. Did you or any other household member eat smaller meals in a day because of lack of resources to obtain enough?

MaleFemale

27.721.4

45.243.9

18.520.9

8.613.8

E06. Did you or any other household member eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough Food?

MaleFemale

31.222.6

43.344.5

16.919.3

8.613.6

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household because there were not enough resources to go around?

Male Female

44.836.6

36.737.2

13.117.7

5.48.5

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?

Male Female

55.645.1

30.935.1

9.213.0

4.26.7

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

Table 3 shows that female headed households were more food insecure than

the male headedhouseholds. This situation is attributed to various forms of

discrimination, which make female-headed households more vulnerable to

food insecurity and poverty. Although the position of women in agricultural

food chains is critical, they encounter many obstacles due to restricted land

rights, inadequate education and outdated social traditions which usually limit

their ability to improve food security status for their households and

communities at large. Women also face different forms of discrimination, such

as greater reluctance on the part of input providers to provide credit for

fertilizer purchases for female headed households than for male headed

26

households and less scope to borrow money or to buy food on credit.

Consequently, food security experts affirm the need to support the

contribution of women to food security by guaranteeing equal constitutional

rights to land and property, involvement in the marketplace, and

opportunities for education. Therefore, whether in terms of labour input,

decision-making, access to or control of production resources, gender issues

should be mainstreamed in food security programmes aimed at resolving

food insecurity.

The analysis that follows takes into consideration appendix 4 which takes

into account all the information generated from the 8 questions taking into

consideration the responses to the four possible answer to each of the

questions which were: never, sometimes, often and always (see appendix 4).

27

Table 4: Hunger Indicators by marital status of the household head -

with often and always scale combined

Marital

Status of

Household

Head

E1: Did

you

worry

that

your

househo

ld would

not

have

enough

food?

E2.

Were

you or

any

househol

d

member

not able

to eat

the kinds

of foods

you

preferred

because

of lack of

resource

s?

E3. Did

you or

any

househol

d

member

eat a

limited

variety

of foods

due to

lack of

choices

in the

market?

E4. Did

you or

any

househol

d

member

eat food

that you

preferred

not to

eat

because

of a lack

of

resource

s to

obtain

other

types of

food?

E05.

Did you

or any

other

househo

ld

member

eat

smaller

meals in

a day

because

of lack

of

resourc

es to

obtain

enough

E06.

Did you

or any

other

househo

ld

member

eat

fewer

meals in

a day

because

there

was not

enough

Food?

E07.

Was

there a

time

when

there

was no

food at

all in

your

househol

d

because

there

were not

enough

resource

s to go

around?

E08.

Did you

or any

househo

ld

member

go to

sleep at

night

hungry

because

there

was not

enough

food?

28

Monogam

ous

married

26.5 29.2 21.4 28.3 26.4 25.1 17.9 12.7

Polygamo

us married

45.1 51.6 33 43.4 44.8 42.5 31 24.4

Living

together

54.8 61.7 53.4 60.2 57.5 52.1 50.7 50.7

Separated 35.5 42.4 28.6 38.6 36.1 31.6 26.1 18.4

Divorced 22.8 28 19.3 33.4 26.3 28.1 15.8 14.1

Widow/

Widower

22.8 43.9 29.6 40.2 39 37.9 33.4 21.9

Never

married

18.4 22 15.1 23 19.4 16.3 11.6 10.3

average 16.1 19.9 14.3 19.1 17.8 16.7 13.3 10.9

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

The relationship between marital status of respondents and status of

household food security seems to follow the expected pattern. Table 4 shows

that households headed by unmarried people are more likely to be food

secure than those headed by married people.

The findings reveal that households heads in polygamous marriages are

more food insecure than those in the monogamous marriages. This could be

attributed to the fact that household heads in polygamous marriages require

29

more resources to buy enough food and other basic household needs because

they often have larger household sizes compared to those in monogamous

families. Large household sizes in polygamous families also require a lot of

land for food production, which might not be available due to the high rate of

population in the country. Although households headed by divorced,

separated and widowed household heads are expected to be more food

insecure, households headed by those in a living together type of relationship

registered high levels of food insecurity. The possible explanation for this

finding is that “living together” could be a food security coping strategy by

some household heads compelled to enter into relationships due to financial

constraints.

Table 5: Hunger Indicators by level of education of household head-

with often and always scale combined

Highest Education Level

E1: Did you worry that your household would not have enough food?

E2. Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of lack of resources?

E3.Did you or any household member eat a limited variety of foods due to lack of choices in the market?

E4. Did you or any household member eat food that you preferred not to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food?

E05. Did you or any other household member eat smaller meals in a day because of lack of resources to obtain enough

E06. Did you or any other household member eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough Food?

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household because there were not enough resources to go around?

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?

% % % % % % % %

30

None 36.8 39.7 25.5 39.2 37.9 35.2 27.4 19CPE/

KCPE27.3 30.2 21.3 29.8 28 24.8 16.8 11.2

KCE/ KCSE

17.6 22.5 14.9 19.5 16.7 16.1 11.8 7.7

KJSE 8 20 24 12 8 16 4 4KACE/

EAACE11.1 11.1 7.47 11.1 18.5 18.5 14.8 11.1

Certificate

11.3 16.5 10.5 13.9 8.7 8.9 7 1.8

Non-University Diploma

7.5 10.8 6.6 12.5 8.4 9.1 5.8 5.9

University Diploma

4.8 8.1 8.2 6.4 6.5 8.1 4.8 3.3

Degree-Post Graduate

7.2 9 10.7 9 10.8 6.3 4.5 3.6

Total 7.3 9.3 7.2 8.5 8 7.9 5.4 3.6

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013

Education was found to have a significant and positive relationship with

household food security as shown in table 5. The findings indicate that

households with relatively better educated household heads are more likely

to be food secure than those headed by uneducated household heads. The

table shows that of those who are always and often hungry 19% have never

gone to school, 11.2 % are CPE/ KCPE holders and those who are least hungry

3.6% are university graduates.

31

Table 7: Hunger Indicators by age group of the household head-with

often and always scale combined

Age group of household head

E1: Did you worry that your household would not have enough food?

E2. Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods

E3. Did you or any household member eat a limited variety of foods due to lack of

E4. Did you or any household member eat food that you preferred not to eat because

E05. Did you or any other household member eat smaller meals in a day because

E06. Did you or any other household member eat fewer meals in a day because there

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there

32

you preferred because of lack of resources?

choices in the market?

of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food?

of lack of resources to obtain enough?

was not enough Food?

because there were not enough resources to go around?

was not enough food?

% % % % % % % %Below

14 Years

33.3 33.3 33.3 33.3 22.2 22.2 33.3 22.2

15-24 Years

25.3 23.8 18.4 25.6 23.1 23.4 16.9 12.1

25-34 Years

25.9 29.8 19.3 26.6 24.6 23 16.5 12.8

35-44 Years

25.1 29.2 20.6 27.9 26.2 23.7 17.7 12

45-54 Years

30.4 33 24.7 31.6 31.3 28.6 21.4 15.6

55-64 Years

34.5 39.6 27.5 36.9 35.4 33.8 28 20.6

Above 64 yrs

37.7 40.7 31 40.2 37.6 36.5 27.6 21.2

Total 15.2 16.4 12.5 15.9 14.3 13.7 11.5 8.3

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

As shown in table7, household heads in the age group of below14 years are

more food insecure than those in the age brackets of 15-24 and 25-34 years.

Some children aged between 12-14 years were household heads due to early

marriages and some became household heads after the death of their

parents; hence, they were more vulnerable to food security because they had

little capacity to produce or access enough food. On the other hand,

household heads in the age group of 15 -34 years are stronger (youthful) and

probably have better education which enables them to engage in various

33

productive activities. Hence, they are more food secure than those in the age

bracket of below 14 years. The age of the household head has a negative sign

showing an inverse relationship between the age of household head and food

security. It indicates that an increase of age year in the age of household

head decreases the chances food security. For instance, the household heads

in the age groups of 35-44, 45-54 and 55-64 years and more than 64 years

are more food insecure than those in the age brackets of 15-24 and 25-34

years. This could be attributed to the fact that the youth have a greater

productivity potential than the elderly. Household heads in the age bracket of

55-64 and those more than 64 years are the most food insecure and their

vulnerability to food insecurity is not surprising when considered in the

context of life for older adults. For instance, their income is often limited with

many depending on pension and Social Security benefits, with the majority of

seniors not working or retired. Further, older adults often experience disability

or other functional limitations. In addition to lacking money to purchase food

products, older adults face unique barriers less often experienced by other

age groups in accessing enough food and adequate nutrition. Research has

shown that food insecurity in older adults may result from one or more of the

following: functional impairments, health problems, and/or limitations in the

availability, affordability, and accessibility of food (Lee & Frongillo, 2001).

Additional contributing factors to food insecurity among the elderly include

lack of mobility due to a lack of transportation and an inability to use food

because of health problems or disability.

34

Table 6: Hunger Indicators by household size

Household size 1-3 House Hold members

4-3 House Hold members

More than 6 House Hold members

% % %

E1: Did you worry that your household would not have enough food?

Never 34.6 25.7 15.6

Some times 41.6 45.3 43.8

often 13.5 16.4 24.1

always 10.2 12.6 16.6

E2. Were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of lack of resources?

Never 28.6 19.6 13.8

Some times 44.2 47.3 43.3

often 17.9 20.4 27.2

always 9.3 12.7 15.7

E3. Did you or any household member eat a limited variety of foods due to lack of choices in the market?

Never 45.1 37.5 29.4

Some times 35.3 38.9 40.2

often 12.5 14.4 20.4

always 7.1 9.2 10

E4. Did you or any household member eat food that you preferred not to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food?

Never 29.7 20.6 14.3

Some times 43.7 47.4 46.7

often 18.3 20.4 25.5

always 8.3 11.6 13.5

E05. Did you or any other household member eat smaller meals in a day because of lack of resources to obtain enough?

Never 34.5 24.4 14.1

Some times 41.2 46.4 46

often 16.5 19 25.5

always 7.7 10.2 14.4

E06. Did you or any other household member eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough Food?

Never 36.9 27.6 17

Some times 40.4 44.3 46.2

often 15.7 17.8 21.2

always 7 10.3 15.5

E07. Was there a time when there was no food at all in your household because there were not enough resources to go around?

Never 51.6 40.9 30.1

Some times 30.6 38.8 42.5

often 12.5 14.1 18.8

always 5.3 6.2 8.6

35

E08. Did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food?

Never 58.3 52.7 41.1

Some times 28.8 32.1 37.5

often 9.1 10 13.9

always 3.8 5.2 7.4

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Household Survey on Food Security June 2013.

The results in table 6 show that the incidence, depth and severity of food

insecurity were high among families with large household sizes than among

those with small household sizes. This is because the larger the household

size, the greater the responsibilities, especially, in a situation where many of

the household members do not generate any income, but only depend on the

household head. As family size increases, the amount of food for consumption

in one’s household increases thereby that additional household member

shares the limited food resources. An increase in household size also

indirectly reduces income per head, expenditure per head and per capita food

consumption. In areas where households depend on less productive

agricultural land, increasing household size results in increased demand for

food. This demand, however, cannot be matched with the existing food

supply from own production and this ultimately leads to household food

insecurity.

3.2 Food Storage and preservation

Food storage and preservation is a key factor in determining household food

security as it ensures availability of food for later use, reduced wastage,

preparedness for catastrophes, emergencies and periods of scarcity as well as

36

protection from animals or theft among others. Figure 1 shows the participant’s

response to the question of storage for perishable food.

Figure 1: Storage of perishable foods

Hanging in own

house; 460.0%

Nothing to store;

86.6%

Granary; 3.9% Others -3.7%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security Baseline June 2013

Most of the respondents (86.6 percent) said that they did not have food to store.

13.4% who had something to store used old-fashioned and unreliable which include;

granaries 3, hanging in the house and other methods as shown in figure 1. These

methods of storing perishable food stuffs are old-fashioned and unreliable and often

lead to expiry of food before consumption. Since most perishable foodstuffs

especially vegetables and fruits are produced seasonally, proper storage of

perishable foodstuffs should be adopted to prevent food wastage. The high

37

percentage of households that do not have perishable food to store is to some

extent caused by serious losses due to lack of good storage equipment.

Storage of perishable foods also poses a challenge to the women respondents in a

similar study. Findings on perishable foods as shown in chart 4 below showed that

about 56 percent of women did not have anything to store in this category of

perishable foods. Those who stored in boxes and crates were only 8.8 percent,

putting in cupboards was 7.6 percent, stored in open air 6.7 percent and drying in

the sun 5.9 percent.

Figure 2 shows the participant’s response to the question of storage for non-

perishable food

Figure 2: Storage of non- perishable food

Nothing to store;

50.5%

Granary; 26.0%

Hanging in the own

house; 10.7%

Other(specify), 12.7%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security June 2013

Figure 2 shows that majority of people 26 percent use granaries to store non-

perishable food, 10.7 percent hang foodstuffs inside their houses and 12.7

38

percent use other methods. These findings reveal that many people use

traditional methods of food storage that are unreliable because they are

either ignorant of the contemporary food storage mechanisms and/or cannot

afford modern food storage equipment or facilities. It also shows that many

people have not adopted post-harvest technologies in food storage.

Moreover, the research findings reveal that 50.5percent of the respondents

did not have food to store. This implies that most households only had little

food for immediate consumption and nothing to store for future use.

Therefore, there is a high level of food un-sustainability in the country, which

is a manifestation of food insecurity. This situation is partly attributed to poor

crop production and limited capacity to buy and store enough food for future

consumption. Lack of food to store is also caused by post-harvest losses

before storage among other constraints.

Figure 3 shows the participant’s response to the question of preservation of

perishable food

Figure 3: Preservation of perishable food

39

has something to preserve;

23.9%

has nothing to preserve; 76.1%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security Baseline June 2013

Those who had perishable food to preserve accounted to 23.9 percent while

majority of respondents 76.1 percent reported that they did not have perishable food

to store. The high percentage of people not having perishable food to store is also

attributed to the fact that many individuals avoid preserving perishable foodstuffs

because they lack effective preservatives as was noted by some participants. For

instance, in Mombasa and Kwale Counties, the respondents stated that due to lack of

preservatives and value addition for perishable foodstuffs they often abandon fruits

such as mangoes and tomatoes to rot in the farms. Thus, farmers incur heavy losses

during harvesting seasons for fruits and middlemen exploit them by buying their

produce at very low prices. Therefore, value addition techniques should be

encouraged at the village level to prevent wastage of perishable food and to create

employment opportunities. Moreover, value addition will enable farmers to get

better returns from their produce.

Figure 4 shows the participant’s response to the question of preservation for

perishable food

Figure 4: Preservation of non-perishable food

40

has some-

thing to preserve;

49.1%has nothing to preserve; 50.9%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security Baseline June 2013

Almost half of the respondents had non-perishable food to preserve at 49.1

percent while 50.9 percent had no food to preserve. Despite many challenges

faced in food preservation majority had no problem on how to preserve food

since they don’t have and hence preservation is not a challenge to them.

However in contrast those who had food to preserve did so with traditional

methods including use of ash which when coupled with poor storage method

led to huge loses directly and indirectly. As also reported during the survey

food stored using these methods also lost quality due to gradual attack by

pest and disease e.g. Afflatoxin producing organisms.

3.3 Main Sources of Livelihood

Households have sustainable livelihoods when they can cope with and

recover from shocks and stress and can maintain their capabilities and assets

without undermining their natural environment. Sustainable livelihood refers

41

to people’s capacity to generate and maintain their means of living, enhance

their well-being and that of future generations (International Federation of

Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2006).

Figure 5 below shows the participant’s response to the question of the main

source of livelihood

Figure 5: Main source of livelihood

0.0%10.0%20.0%30.0%40.0%

39.4%

20.9% 16.9% 16.0%

3.2% 2.1% 0.7% 0.6%

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security Baseline June 2013

The findings of this study shown in figure 5, indicates that the sources of livelihood

in the counties are own production at 39.4 percent casual labour (agriculture and

non-agriculture related) 20.9%, regular monthly salary 16.9%, trade/small

businesess16%, sale of livestock 3.2%, remittance from relatives 2.1%, while help

from relatives and public stood at 0.7 and 0.6 percent respectively. These findings

shows that there are various sources of livelihood, but agriculture (own production

39.4 percent) is dominant countrywide. Nonetheless, trade and monthly salary is the

main source of income in urban counties such as Nairobi and Mombasa County.

42

1.3 Gender perspectives

Figure 1: What do people do when they don’t have adequate food

Borrowed

Food

Helped

by rela

tives

Purchase

d Food on cr

edit

Adults at

e less/

skipped

mea

ls

Sent ch

ildren

to liv

e with

relati

ves

Sold Househ

old items

Sold an

imals

(goats

, shee

p, cows)

Receive

d relie

f food

Casual

labour

Steali

ng

Plant sh

ort term

crops

Engag

ed in

prostitution

Bought fo

od

Ate wild

fruits

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Female Male

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 2013

The findings reveal that, during periods of food shortages, men and women

adopt different coping strategies. The main strategies adopted by women at

100 percent each include engaging in prostitution, and eating wild fruits while

a similar proportion of the men said they plant short term crops, sell

household items and, send their children to live with relatives. Other main

strategies adopted by men included purchasing food on credit at

approximately 82 percent while another 74 percent sold animals and over 50

44

per cent, borrowed food as a coping strategy. The proportion of women and

men that engaged in casual labour so as to get food was 53.5 and 46.5

percent respectively. About sixty percent of women compared to 40 percent

of men were helped by relatives. The other major strategy for the women was

stealing at about 56 percent compared to 44 percent among their male

counterparts.

Figure 2: Perceptions of land use by male and female respondents

Farming

Livest

ock ke

eping

Building R

ental

houses

Constructi

on of home/h

ouse

Leasin

g out

Use as

loan se

curity

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

MaleFemale

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 2013

While an equal proportion of men and women cited using land as loan

security, the proportions for the two genders were diverse on all the other

variables. For example 100 percent of men used land for construction of

home/house compared to 0 percent of women using the land for the same

purpose. The findings show more men than women, use land for the other 45

three variables, which included livestock keeping, farming and, leasing out.

The only variable, where more women (60 per cent) than men (40 per cent)

utilized land differently is in the building rental houses.

Figure 3: Access to Government food support programmes as

perceived by men and women respondents

Farm in

puts

Foodstu

ffs

Loans/fi

nancia

l support

Capaci

ty build

ing in fa

rming m

ethods

Value a

ddition to ag

ricultu

ral produce

Through

relev

ant m

inistries

Through

provincia

l Adminsitr

ation

School fe

eding p

rogra

mme0

20406080

100120

MaleFemale

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 201

The most conspicuous finding, in figure 17, is the proportion of women, at

100 percent compared to 0 percent of men, who said they received

Government support in the form of value addition to agricultural produce. The

largest proportion of men said they received support in the form of foodstuffs

and provision of farm inputs at approximately 75 percent and 70 percent,

respectively. Loans/financial support at about 63 percent and capacity

building in farming methods were the other main forms of support mainly

cited by the men. On the other hand, it is only under school feeding

46

programme where more women than men at 57.1 percent and 42.9 percent,

respectively, received government support.

Suggestions to Improve Government Food Support Programmes

The study sought recommendations of the male and female participants on

how the government food support programmes could be improved. The

findings on the recommendations are presented in Figure 18.

Figure 4: Suggestions on how government food programmes can be

improved

Provid

e finan

cial su

pport

Increase

Agric. E

xtensio

n servi

ces

Sensiti

ze Community

Lead

ers

Provis

ion of farm

inputs/

implem

ents

Making p

rogrammes

access

ible to all

Provis

ion of storag

e faci

lities

Transpare

ncy in id

entificati

on of ben

eficia

ries

Increasi

ng the s

upport0

20

40

60

80

100

120

MaleFemale

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 2013

The largest proportion of men at 100 percent compared to 0 percent among

the women, recommended the provision of storage facilities. The largest

number of women at 62.5 percent compared to men at 37.5 percent

47

recommended the programmes be made accessible to all. While an equal

proportion of men and women recommended provision of farm

inputs/implements, the lowest proportion of women at approximately 26

percent recommended increase of extension services while the lowest

proportion of men, at about 37.5 percent recommended the programmes be

made accessible to all.

Economic Activities that Hinder the Achievement of Food Security

Men and women normally engage in different economic activities that have a

bearing on Household (HH) food security. The study, thus gathered views on

the views from the male and female respondents on the economic factors

that hinder achievement of food security, the findings are presented in Figure

20.

Figure 5: Economic issues that hinder achievement of food security

in the region

48

High Cost o

f seed

s

High Cost o

f fertl

izers

High co

st of m

achinery

Low yield

ing lives

tock bree

ds

Lack o

f storag

e faci

lities

Lack o

f mark

et

Lack o

f exte

nsion se

rvices

Poor infra

nstructu

re

Lack o

f cred

it faci

lities

Small

/Uneco

nomical p

ieces

of land

Unsecure

land te

nure

Unemploym

ent

Income issu

es/litt

le income

Presen

ce of m

iddlemen

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

MaleFemale

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 2013

The findings illustrate there are differences in magnitude of responses

between men and women. The largest proportion of women respondents said

presence of middlemen and also lack of storage facilities, at 100 percent

each, were major hindrances to food security. The other major challenges

cited by women included high costs of seeds at 66.7 percent and unsecure

land tenure and lack of market at 60 percent each. The largest proportion of

male respondents cited small/uneconomical pieces of land and lack of

extension services at about 78 percent each. An equal proportion of men and

49

women cited lack of credit facilities, low yielding breeds of livestock and, high

cost of farm machinery as hindrances to food security.

Options that could be used to Ensure Attainment of Food Security

The study gathered views on ensuring food security, in an effort to gauge

whether there were different recommendations from the male and female

informants. The findings are presented in Figure 21.

Figure 6: Options that could be used to make sure that they have

adequate food

Water h

arvesti

ng

High yie

lding crop va

rieties

Improve

d infra

nstuctu

re

Provis

ion of irrig

ation

Access

to cred

it/finan

ce

Affordable s

eeds

Affordable f

ertlize

rs

Access

to exten

sion se

rvices

Improve

d securit

y

Capaci

ty build

ing in Agri

culture

Creation of e

mploymen

t

Provis

ion/acces

s to la

nd

Provis

ion of educati

on

Form

ation of co

-operative

s

Value a

ddition0

20

40

60

80

100

120

MaleFemale

Source: AWSC/KNBS Baseline Survey on Food Security, June 2013

50

The largest proportion of female respondents at 100 percent compared to 0

percent among their male counterparts recommended improvement of

security. The other major recommendations among the women were creation

of employment at 75 percent, provision of education and formation of co-

operatives at 66.7 percent each and provision/access to land at 57.1 percent.

The major recommendations among the men included improvement of

infrastructure and provision of affordable fertilizers at 80 percent each, water

harvesting at about 68 percent and, provision of affordable seeds at about 65

percent.

51

PART 2: DOCUMENTING WOMEN’S EXPERIENCES WITH FOOD

SECURITY

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Food security remains a serious challenge to many communities in Kenya

particularly the women. Although they are responsible for more than half of

the Kenya’s food production, they continue to be regarded as home

producers or assistants on the farm, and not as farmers and economic

agents on their own right. Their role in securing food security has mainly

remained invisible to many policy-makers. Moreover, literature shows that

women receive a small fraction of assistance for agricultural investments. In

Africa for example, women receive less than 10% of small farm credit and

only 1% of total credit to the agricultural sector, (IFPRI, 2001).

Gender-based inequalities along the food production chain “from farm to

plate” hinder the attainment of food and nutritional security. Empowering

women farmers is vital to lifting rural communities out of poverty, especially

as many developing nations face economic crisis, food insecurity, HIV/AIDS,

environmental degradation and climate change and increased urbanization.

Thus, maximizing the impact of agricultural development on food security

entails enhancing women’s roles as agricultural producers as well as the

primary caretakers of their families. To this end, research findings on food

52

security reveal that countries have taken decisive steps towards eliminating

food insecurity in the endeavor to create hunger free nations and restore

dignity to their citizens (Rebuilding the Broken African Pot, 2012).

No doubt, food security is a primary goal of sustainable agricultural

development and a cornerstone for economic and social development.

Kenya’s Constitution (2010) for instance, with its devolved governance

system, offers a great opportunity for counties (which are mandated to

coordinate agricultural activities) to develop policies and programmes that

ensure food security. While about a third of Kenya’s population is considered

to be food insecure, the government has made several commitments to

eradicate food insecurity. These efforts include the Millennium Development

Goals (MDG), the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme

(CAADP); Maputo Declaration, 2003) and Vision 2030 among other policy

pronouncements. Thus, the Kenya Constitution (2010) and the National Food

and Nutrition Security Policy (Sessional Paper 1 of 2012) provide great

opportunities for all stakeholders to engage and ensure zero tolerance to

hunger among all Kenyans.

FAO states that, food security is when one has a household's physical and

economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that fulfils the

nutritional needs and food preferences of that household for living an active

and healthy life. It is realized when all people, at all times, have physical,

social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet

their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

53

Further, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), view food security

at the household level as access by all members at all times to enough food

for an active, healthy life which includes at a minimum: ready availability of

nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and an assured ability to acquire

acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (that is, without resorting to

emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, or other coping strategies).

Towards efforts to achieve zero tolerance to hunger in Kenya, the African

Women’s Study Centre (AWSC) undertook the project: Towards Food and

Nutrition Security - Implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) which aimed to

promote and advocate for the implementation of Article 43 (1)(c) of the Bill

of Rights in the Kenya Constitution (2010) which states that “Every person

has the right to be free from hunger, and to have adequate food of

acceptable quality,” (Constitution of Kenya, 2010).

The AWSC which is based at the University of Nairobi is a policy, research,

training and advocacy Centre that works to bring women’s experiences into

mainstream knowledge. It is a multi-disciplinary Centre with expertise from

all the Colleges of the University including: Colleges of Humanities and Social

Sciences, Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, Education and External

Studies, Health Sciences, Architecture and Engineering and Biological and

Physical Sciences. The main objective of the research was to document and

share with the stakeholders, government agencies and concerned

organizations nationally and internationally the findings, challenges and

recommendations on women’s experiences in food security. Key research

54

areas of interest include women livelihood strategies, access and use of land,

food storage, livestock assets and ownership, food access and coping

strategies.

2.2 METHODOLOGY

This research was conducted by first examining both published and

unpublished secondary sources of data such as thesis, dissertations,

newspapers, books and journal articles on food security. A desk review of

countries with best food security policies and programmes was also

conducted to draw lessons that can be used to improve food security in

Kenya.

The sampling methodology for the study sites was based on Kenyan

Ecological Zones (AEZs) which classified into six Agro-ecological Zones. The

AEZs include: Upper Highlands, Upper Midlands, Lowland Highlands, Lowland

Midlands, Inland Lowlands and Coastal Lowlands and out of the 47 counties

in Kenya, 13 counties were randomly selected for the study while Nairobi and

Mombasa counties were purposefully added as they consist 100% urban

population according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). The

15 counties sampled for the survey were; Kisii Nairobi, Kiambu, Nakuru,

Elgeyo-Marakwet, Kirinyaga, Kajiado, Bomet, Makueni, Bungoma, Taita

Taveta, Migori, Samburu, Turkana, Baringo, Isiolo, Kwale, Mombasa, Nandi,

Laikipia. Among these counties, nine of them were selected for the Phase

One of the study.

55

Five constituencies were further sampled from each county for the survey

(except Laikipia County which has only three constituencies. Thus, all were

selected). From the selected constituencies, five wards were picked for the

study. Where the constituencies were less, the five Wards were picked from

the pool of what was available. In each County, four wards out of the five

represented the rural population while one ward represented the urban

population in an 80:20 national ratio of rural to urban population (see the

list of selected counties and wards for phase I and phase II of the

study in appendix 1).

Fieldwork took place in two phases: Phase I and Phase II. Phase I took place

between 16th and 19th of April 2013 and covered the following counties:

Baringo, Bomet, Kajiado, Kiambu, Laikipia, Makueni, Mombasa, Nairobi and

Nakuru. Phase II took place between 14th and 18th of June 2013 in Elgeyo-

Marakwet, Kirinyaga, Kisii, Kwale, Kisumu and Bungoma counties. Figure 2

reflects the commissioning of the study in one of the phases.

The methods (techniques) used for gathering data in the field to capture

women’s experiences were face-to-face, in-depth interviews, focus group

discussions (FGDs), oral testimonies and debriefing as shown in table 1. All

of these methods were organized according to age groups. In the face-to-

face, in-depth interviews, the women were grouped into age categories

as: 15-24 years, 25-34 years, 35-49 years and 50 and above years. They

were to be interviewed from the five selected constituencies or wards of the

56

counties making a total of at least 40 respondents. In every age group, one

of the respondents had to be a leader.

The FGDs were organized into two age groups which included less than 40

years and 40 and above years. A total of 3 FGDs were planned for each

county where two FGDs were planned to take place in the rural areas of the

counties and one in an urban area of the county. Using the results from the

FGDs, the study anticipated to capture women’s knowledge, perceptions,

perspectives and experiences of both younger and older women in food

security. Four oral testimonies were planned for in each county. They

included two age categories of women aged between 50-65 years and those

aged 66 and above years. The expectations were to capture the historical

perspective on food security among these older women. It was deemed

necessary that at least one of these oral testimonies would take place in an

urban area of the county.

The method of debriefing was in the form of a meeting planned in each of

the counties with the representatives of the county management (Governor,

County Assembly, other development officers and selected representatives

of the participants in all the interviewed areas in the county). These

representatives constituted about twenty to twenty five people. This was

part of data collection process and took place in an agreed upon venue. The

participants were purposively selected based on the cited age groups and

Wards.

57

Table 1: Types of Study Instruments and the Number of Respondents per County

No CountyTool

In-depth/ face-to-face

Oral interviews

FGDs Debriefing

1. Nairobi 36 4 3 12. Mombasa 45 4 3 13. Kiambu 40 4 3 14. Bomet 40 4 3 15. Makueni 40 4 4 16. Baringo 40 4 3 17. Kajiado 36 5 5 18. Nakuru 40 4 3 19. Laikipia 43 4 3 110. Elgeyo

Marakwet40 4 3 1

11. Bungoma 41 4 3 112. Kisumu 40 4 3 113. Kwale 40 4 3 114. Kirinyaga 44 4 3 115. Kisii 32 4 3 1

Figure1: Commissioning of the Study

58

Figure2: Field Data Collection.

2.3 RESEARCH FINDINGS

2.3.1 Livelihood Activities

a. Source of IncomeAs indicated in figure3, it was evident that majority of women derived their livelihoods from the sale of

agricultural products (27 percent) and petty trading/business (26 percent). Temporary work was made up

of 14 percent while 13 percent managed their livelihood from sale of animals. It was clear that majority

women had resorted to agriculture and business as the only means of livelihood. This may mean that with

low educational attainment it may be difficult to get employment in the formal sector or that formal job

may be scarce in the rural areas where 80 percent of the study focused.

59

Figure3: Percentage Livelihood Activities of Respondents (Source of Income)

Sale of agricul-

tural prod-ucts29%

Sale of animals13%

Sale of fish1%

Rural temporary work14%

Monthly salary

7%

Remittance8%

Business/ trade26%

Renting houses1%

Pension1%

From women group/ social group contribution

1%

Source: AWSC/KNBS women experiences on Food Security, 2014

b. Income ExpenditureAccording to the results on the figure4, the highest expenditure (26.9 percent) on the income earned was

spent on buying food, 24.1% on paying school fees and 16.3% on medical bills. Other areas where the

income was spent included buying clothes, saving, investment and paying rent. The expenditure reflects a

woman’s strained budget and thus less is used on food which implies that the food bought may be

insufficient as women struggled to meet the various needs. Also, it may explain why they save little

money with the financial institutions, buy assets or make other types of investments.

60

Figure4: Percentage Income Expenditure among the Respondents

Paying s

chool fees

Buying f

ood

Buying c

loths

Medica

l bills

Saving u

nder socia

l groups

Saving i

n financia

l institutions

Buying A

ssets

Investm

ent

Helping n

eighbours

and re

latives

Other basi

c nee

ds

paying r

ent

repay

ing loan

other0.0

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

30.0

24.126.9

8.0

16.3

2.5 1.5 1.02.5 1.8

7.6

3.11.6

3.1

Income Expenditure

Expenses categories

Perc

enta

ge

Source: AWSC/KNBS women experiences on Food Security, 2014

2.3.2 Coping Strategies

Figure 5 presents an analysis that was done by Dr. Wanjiru Gichuhi

(Population Studies and Research Institute, U.O.N) in comparing the

Strategies that men and women adopt to confront food shortages. Results

show that during times of food shortages men and women adopted different

coping strategies. It was observed that some strategies like prostitution and

eating wild fruits were almost exclusively reserved for women while none of

the men said they were engaged in such activities for survival. The data