Viet Nam - ADPC · enabling environment & opportunities viet nam strengthening disaster and climate...

Transcript of Viet Nam - ADPC · enabling environment & opportunities viet nam strengthening disaster and climate...

ENABLING ENVIRONMENT & OPPORTUNITIES

Viet Nam

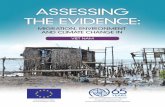

STRENGTHENING DISASTER AND CLIMATE RESILIENCE OF SMALL & MEDIUM ENTERPRISES IN ASIA

The iPrepare Business facility for engaging the private sector in Disaster Risk Management is a joint initiative by the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) through the Integrated Disaster Risk Management (IDRM) Fund and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH within the framework of the Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management (GIDRM). It focuses on building disaster-resilient businesses in the region through partnerships to strengthen the resilience of the private sector, particularly SMEs; providing technical assistance in strengthening resilience on a demand-driven basis; supporting governments in strengthening the enabling environment that promotes risk sensitive and informed investments by private sector; and facilitating knowledge sharing at the regional and national levels.

The Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) is an independent regional non-profit organization that works to build the resilience of people, communities and institutions to disasters and climate change impacts in Asia-Pacific. Over the past 30-years, ADPC has expanded its scope and diversified its operations for a programmatic approach that offers long-term and sustainable solutions to addressing the underlying causes of disasters and climate change risks.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is a multilateral development finance institution dedicated to reducing poverty in Asia and the Pacific. ADB assists its members, and partners, by providing loans, technical assistance, grants, guarantees, and equity investments to promote social and economic development. With support from the Government of Canada, ADB established the Integrated Disaster Risk Management (IDRM) Fund in 2013, to assist the development of proactive IDRM solutions on a regional basis within ADB’s developing member countries in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam. The Fund provides a strong mechanism for supporting ex ante investment in IDRM and complements the existing financing modalities of ADB for supporting ex post relief and recovery activities.

In order to respond more effectively to the global challenges posed by disaster risks, the German Government, led by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), has founded the Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management (GIDRM). The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ GmbH) has been commissioned to manage the GIDRM. The aim of the Global Initiative is to bring together German and regional experts from the public and private sectors, civil society and the academic and research community, to facilitate mutual learning across national boundaries as well as to develop and pilot innovative disaster risk management solutions. The Global Initiative focuses on three priority areas including Disaster Response Preparedness and Civil Protection; Critical Infrastructure and Risk-sensitive Economic Cycles; and Early Warning Systems.

Publication details On behalf of the iPrepare Business facility,Published by the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC) SM Tower, 24th Floor 979/69 Paholyothin Road, Samsen Nai Phayathai, Bangkok 10400, ThailandTel: +66 2 298 0682-92 Fax: +66298 0012-13E-mail: [email protected]

i

Acknowledgements

The iPrepare Business facility wishes to thank all the individuals and organizations who contributed to this report, and who continue to support the regional project on “Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Small and Medium Enterprises in Asia’’.

The report was prepared by the iPrepare Business facility, headed by Aslam Perwaiz. The policy research, analysis and report-writing was led by Dr. Mary Picard, ADB International Consultant, with support from Tran Hoang Yen, ADB Viet Nam National Consultant, who also coordinated the SME Resilience Survey with national partners, analyzed and presented the survey results.

The success of the Viet Nam SME Survey, the January 2016 mission by the International Consultant, and implementation of the broader project within Viet Nam has been possible due to the continuing support and cooperation of the country partner, the Ministry of Planning and Investment, in particular the Agency for Enterprise Development and The Assistance Center for SME-North Viet Nam (TAC-Hanoi). Special thanks are extended to Le Manh Hung and Nguyen My Anh of TAC-Hanoi for their support, as well as to all those who met with the team throughout the project, including those listed in Annex 2 of this report.

Table of Contents

Acronyms ivKey Terminology viExecutive Summary viiiIntroduction xii

01 Towards Disaster-Resilient SMEs 2What is disaster resilience? 3Characterizing SME disaster risk in the policy context 4

02 SMEs in Viet Nam – characteristics and risks 7SMEs in Viet Nam’s Economy 9SME Disaster and Climate Risk in Viet Nam 10The survey group 11

03 How disaster-resilient are SMEs? – The SME Survey 12Findings on Risk Exposure and Impacts of Previous Disasters 14Findings on Business Continuity Plan Adoption 16Findings on Incentives and Training Needs 16Findings on disaster preparedness 17Findings on financial coping mechanisms 19Survey overview and conclusions 20SMEs and the ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ system 23

04 Including SMEs in the systems for ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ and climate change adaptation 23

SMEs and climate change legislation and institutions 26Roadmap Issues for SME inclusion in CCA and NDPC system(s) 27The SME Development and Promotion System 29

05 Disaster resilience in Viet Nam’s support for SME development 29SME access to Finance 30New Law on SME support in preparation 32Private Sector & NGO Support for SMEs 32Gender and SME Development and Resilience 34Roadmap Issues 34Approaching a roadmap process for SME disaster resilience 36

ii ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

CONTENTS iii

06 Towards a Road Map for SME Disaster Resilience in Viet Nam 37Who are the stakeholders and experts? 38How stakeholders can be engaged 39Which policy mechanisms or actions might be addressed 39What issues might be considered 39Disaster Insurance and Risk Financing 41

Annex 42

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1 Legal definition of very small (micro), small and medium enterprises in Viet Nam under Decree 56 8

Figure 2 Classification of enterprises based on size of labor force and form of business ownership 2013 9

Figure 3 Number of SMEs in Viet Nam 2007-2013 10

Figure 4 The relative frequency of natural hazards in Viet Nam 11

Figure 5 Distribution by major industry sectors 13

Figure 6 Distribution of respondents according to number of employees 14

Figure 7 Hazards that can potentially affect business operations by the respondents 15

Figure 8 Top 3 reasons for not preparing a BCP so far 16

Figure 9 Motivations for SMEs that had developed BCPs 17

Figure 10 Whether BCP should be compulsory 18

Figure 11 Attendance at BCP-related training 18

Figure 12 Attendance at disaster risk management-related training 19

Figure 13 Willingness to participate in activities to support SMEs 20

Figure 14 Distribution of disaster risk financing mechanisms used by respondents 21

Acronyms

AED-MPI Agency for Enterprise Development, MPI

ADB Asian Development Bank

ADPC Asian Disaster Preparedness Center, Bangkok

AEC ASEAN Economic Community

APBSD ASEAN Policy Blueprint for SME Development

APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ASEC ASEAN Secretariat

BCP business continuity plan

BCM business continuity management

BMZ German Ministry for Economic Development and Cooperation

CBDRR community based disaster risk reduction

CBDRM community based disaster risk management

CCA climate change adaptation

CCFSC Central Committee on Flood and Storm Control (now replaced by SCNDPC since March 2015)

DIT Department of Industry and Trade (DIT)

DNDPC Department of Natural Disaster Prevention and Control, MARD

DMC Disaster Management Center, MARD

DRR disaster risk reduction

DRM disaster risk management

FIE foreign invested enterprise

FSC flood and storm control

GIDRM Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH

GSO General Statistics Office, PMI

iV ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

ACRONyMS V

GVCs global value chains

HCMC Ho Chi Minh City

HHB Household Business

IDRM Fund Integrated Disaster Risk Management Fund, ADB

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

MBB Military Bank

MPI Ministry of Planning and Investment

MARD Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

MONRE Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment

MSMEs micro, small and medium enterprises

NCFAW National Committee for the Advancement of Women

NDPC ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ (used when referring to the specific scope of the Viet Nam law, otherwise the term DRM is used)

NSCCC National Steering Committee on Climate Change

NS-NDPC National Strategy on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control

NTP-RCC National Target Program to Respond to Climate Change

SC-NDPC Steering Committee for Natural Disaster Prevention and Control (replaced CCFSC from March 2015)

SMEs small and medium enterprises

SMEDF Small and Medium Enterprise Development Fund

SMEWG Small and Medium Enterprises Working Group - APEC

SOE state owned enterprise

SOM Senior Officials’ Meeting - APEC

TAC-Hanoi The Assistance Center for SME-North Viet Nam, Ministry of Planning and Investment, MPI

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

VINASME Viet Nam Association of Small and Medium Enterprises

VCCI Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry

VWU Viet Nam Women’s Union

Key Terminology

Business continuity management (BCM) – (ISO 22301:2012)

“Holistic management process that identifies potential threats to an organization and the impacts to business operations those threats, if realized, might cause, and which provides a framework for building organisational resilience with the capability of an effective response that safeguards the interests of its key stakeholders, reputation, brand and value-creating activities.”

Business continuity plan (BCP) – (ISO 22301:2012)

“Documented procedures that guide organizations to respond, recover, resume, and restore to a pre-defined level of operation following disruption.”

Coping capacity – (UNISDR1)

“The ability of people, organizations and systems, using available skills and resources, to face and manage adverse conditions, emergencies or disasters.”

Disaster – (UNISDR)

“A serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.”

Disaster risk management (DRM) – (UNISDR)

“The systematic process of using administrative directives, organizations, and operational skills and capacities to implement strategies, policies and improved coping capacities in order to lessen the adverse impacts of hazards and the possibility of disaster.”

Disaster risk reduction (DRR) – (UNISDR)

The concept and practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to analyse and manage the causal factors of disasters, including through reduced exposure to hazards, lessened vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improved preparedness for adverse events.”

1 UNISDR Terminology 2009. Available at http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology. Other relevant terms defined therein include: disaster risk, emergency response, exposure, hazard, mitigation, preparedness, recovery, risk, vulnerability.

Vi ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

TERMiNOLOGy Vii

Emergency response – (UNISDR)

“The organization and management of resources and responsibilities for addressing all aspects of emergencies, in particular preparedness, response and initial recovery steps.”

Natural disaster prevention and control – (Government of Viet Nam)

This term is used in quotation marks and only when referring to the specific terminology of the English translation of Viet Nam’s Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control (NDPC), as defined in that law Article 3. Otherwise the more universal term DRM is used in this report. The NDPC Law definitions are:

Art. 3(1) “Natural disasters means abnormal natural phenomena which may cause damage to human life, property, the environment, living conditions and socioeconomic activities. Natural disasters include typhoon, tropical low pressure, whirlwind, lightning, heavy rain, flood, flashflood, inundation, landslide and land subsidence due to floods or water currents, water rise, seawater intrusion, extreme hot weather, drought, damaging cold, hail, hoarfrost, earthquake, tsunami and other types of natural disaster”; and

Art. 3(3) “Natural disaster prevention and control means a systematic process involving the prevention of, response to, and remediation of consequences of, natural disasters.”

Resilience (IPCC2)

“The ability of a system and its component parts to anticipate, absorb, accommodate, or recover from the effects of a hazardous event in a timely and efficient manner, including through ensuring the preservation, restoration, or improvement of its essential basic structures and functions.”

2 IPCC. 2012: “Glossary of terms. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation.” Available at http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srex/SREX-Annex_Glossary.pdf

Executive Summary

A disaster-resilient enterprise is one that has the capacity to survive and recover from a disaster that affects it, in a way that enables it to continue to grow and develop, and even improve.

This report presents the results of a survey on the disaster resilience of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and provides a strategic policy analysis of the enabling framework for SME disaster resilience in Viet Nam. It is the result of cooperation between the iPrepare Business facility, and its key country partner, the Ministry of Planning and Investment, in particular the Agency for Enterprise Development and The Assistance Center for SME-North Viet Nam (TAC-Hanoi).

The country report is also part of a Regional Project, “Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Small and Medium Enterprises in Asia”, which is being implemented by the iPrepare Business facility and country partners in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Viet Nam, with the support of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Integrated Disaster Risk Management Fund, a fund financed by the Government of Canada, and the German Ministry for Economic Development and Cooperation (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) within the framework of the Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management (GIDRM).

Specifically, the report is based on desk research on relevant laws, policies, institutions and secondary literature, consultations during a country mission in January 2016, and the Viet Nam SME Resilience Survey undertaken as part of the project. It is divided into 6 parts:

Part 1 looks at what we mean by disaster-resilient SMEs, then frames the discussion in terms of the two main categories of risk that SMEs face – (1) shared community disaster risk, and (2) business continuity disaster risk. It proposes that the existing national system(s) for climate change adaptation (CCA) and disaster risk management - in Viet Nam translated as the system for ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ (NDPC) – provide the most effective and efficient legal, policy and institutional basis for improving SME resilience to shared community disaster risks. For business continuity disaster risks, the national laws and institutions targeted to broader SME development provide the best vehicle for policy intervention. The two guiding questions then asked for the Viet Nam policy analysis are:

1. To what extent do the climate change adaptation and ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ systems either include SME representatives at national level, or integrate SMEs into local institutions, risk awareness campaigns, emergency response and recovery operations at local level?

2. To what extent is climate and disaster resilience factored into the picture of an economically healthy SME through policy schemes targeted at SME development and promotion?

Viii ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

ExECUTiVE SUMMARy ix

Part 2 examines what we know about Vietnamese SMEs’ economic structure from national statistics, and what this can (and cannot) tell us about their disaster risk. A key characteristic is that the vast majority of enterprises in Viet Nam are micro or small – 96% - and almost all of these are in the private sector rather than being government-owned. Of the 368,844 registered enterprises in Viet Nam in 2013, 70% were micro, 26% small, 1.9% medium and 2.1% large. SMEs thus accounted for 97.9% of all enterprises in Viet Nam. Even the formal economy is the thus dominated by small and medium enterprises. In addition, there are many household businesses in the agricultural sector and low-income trading that are recognized but not required to register as enterprises.

Part 3 presents the results of the SME Resilience Survey. The majority of the 442 SMEs surveyed were micro or small, and also mostly young private enterprises established since 2009, with the vast majority also owned by men (71%). The respondents came from a range of sectors and from across the nation. Wholesale and retail trade made up over 40%, construction 17%, ‘other’ (non-classified or multi-sector) 26%, and the remaining sectors 17%. While this relatively small random sample taken across the country cannot reflect all the variations amongst Viet Nam’s 360,000 SMEs, it is broadly representative and gives an insight into the key disaster resilience issues for them.

The survey indicated that both the use of Business Continuity Plans (BCP) and awareness on natural hazard risks, were low. This may be partly attributable to the fact that most of the SMEs began operation since the last major disaster in Viet Nam, in 2009, suggesting lack of direct experience may have led to a lack of awareness or preparedness for future natural hazards and climate change stresses:

Each SME was requested to indicate the 3 hazards with the greatest potential to disrupt their business operations, with 5 hazards emerging overall. These were: power blackout, regional/global economic crises, fire, typhoon, and flood;

More than 90% of the respondents confirmed that they have never experienced a business operation disruption due to a hazard or disaster (which may be because they are young business and there have been no major disaster since 2009);

Almost 80% of the respondents said they have not yet developed a BCP, although 14% said they were preparing one;

The top 3 reasons for not preparing a BCP given by the respondents were that: they had not heard of BCP before; they lacked a budget to prepare a BCP; and they lacked information on how to prepare a BCP.

There is a need for SME awareness and training on both natural hazard risk and BCP:

90% of the respondents had not attended any training related to BCP;

88% of the respondents had not participated in any training related to disaster risk management;

Almost 80% of the respondents confirmed that they would like to participate in activities to support SMEs in Viet Nam to enhance their disaster resilience;

The top 3 incentives identified by respondents were that the government could provide to SMEs to encourage them to be more disaster resilient were: tax credits, deductions, and exemptions; subsidies, grants, and soft loans for disaster preparedness; and provision of technical assistance, consultancy services, or training in BCP preparation and disaster preparedness.

Part 4 and Part 5 of the report overview the laws, policies and institutions underpinning disaster and climate risk management and SME development and promotion. Part 4 looks at the companion systems of ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ (NDPC), which is under the stewardship of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), and climate change adaptation (CCA), under the stewardship of the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MONRE). This analysis examines opportuntities for SME participation and awareness-raising, and mechanisms for cooperation on SME disaster-resilience within the mandates of the high-level national committees and the ministries of MARD and MONRE concerning NDPC and CCA respectively. It indicates that SME and private sector needs are not considered specifically in the policy and implementation processes for climate and disaster risk management, although some projects with partners are moving in this direction. It also notes that the Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control 2013 (Law on NDPC) provides a set of obligations for enterpises that can serve as a good basis for their awareness-raising on disaster risk managment. Part 5 then considers the system for SME promotion, support and development as business enterprises, which is under the stewardship of the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI). The analysis looks at the elements of the system established to support SME development, and the extent to which it takes account of disaster risk for SME business continuity, as well as avenues for cooperation with MARD and MONRE. It finds that disaster risk is not currently a central concern in this system for SME development.

The picture that emerges from Parts 4 and 5 is that, although the legislative and policy mandates of the NDPC and CCA systems, and the SME promotion system are cross-sectoral in intent – the key high-level committees in each include all of MARD, MONRE and MPI - these systems do not currently interact to any significant extent at either a policy or operational level. However, the development of a new law on SME support that is currently being undertaken by MPI provides an opportunity for Viet Nam to lead the region in creating a new focus on disaster resilience as a key component of business continuity for SMEs.

x ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

ExECUTiVE SUMMARy xi

Part 6 uses the report’s findings and analysis to propose a method of tackling a Viet Nam road map for SME disaster resilience. As this will be a Government-led process, these are not specific recommendations, but rather issues for consideration identified throughout the report as “road map issues”. It highlights the fact that SMEs and the industry bodies that represent them need to be seen as the key stakeholders, even though the Government has the central role in determining the legal and policy framework and managing the process. In engaging with SMEs during the road map process it may also be important to conduct specific consultations to ensure views and information are obtained from different industries, a range of provinces and geographical risk profiles, urban and rural settings, and women SME owners. The process itself could also be used to strengthen SME organizations as part of an ongoing mechanism for capacity building, policy implementation and communication between SMEs and Government.

Although it is presumed that MPI would lead a roadmap process, the roles of MARD and MONRE are also identified as central to supporting SME resilience to disasters and climate change. The roadmap process, along with the development of the new law on SME support, in fact provide an opportunity to institutionalize stronger cooperation between these ministries in supporting SME disaster resilience. Engagement of INGOs, development partners, experts and technical institutions already working on SME support in Viet Nam can also add to Viet Nam’s capacity to design and implement effective support programs, given the innovative approaches already demonstrated.

The development of the new law on SME support is an opportunity for Viet Nam to lead the region in a number of ways, including by mainstreaming disaster and climate risk into SME development policy, institutionalizing participation of the private sector in policy implementation and programmes, and reviewing and updating financial incentives for SMEs to reduce risk and prevent damage and loss from disasters. The legal and policy framework could also benefit from revising the SME definition to allow more targeted policy interventions, including the needs of household businesses that are recognized but not currently required to register as enterprises, as well as to provide stronger statistical reporting on SME characteristics.

The other substantive issues mentioned for inclusion in the roadmap process include: development, promotion and support for SME implementation of multi-hazard Business Continuity Management (BCM); support for SMEs and local planning authorities in hazard mapping, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation; a review of barriers to SME uptake of insurance or other risk financing mechanisms; institutional cooperation mechanisms for SME response and recovery support; and using and strengthening existing private sector capacity in disaster resilience and BCM.

Introduction

This report is a strategic policy analysis of the enabling framework for disaster-resilient small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Viet Nam, which also includes the results of a 2015 SME Resilience Survey undertaken as part of the same project.

The report takes into account relevant laws, policies, and government institutional frameworks of Viet Nam, as well as private sector and NGO initiatives that interact with government policy. The focus is on SME business continuity in the face of the major natural hazards that often cause disasters in Viet Nam - especially floods and storms - including a projected worsening of these weather hazards due to climate change, which will also lead to a rise in sea levels. However, the report adopts a multi-hazard approach that encompasses technological and mixed hazards to the extent these are identified as risks for SME business continuity.

The approach also recognizes the importance of general or economic resilience of SMEs and the policies to support this, as the underlying economics affecting SME profitability and development also impact their disaster resilience. For example, SMEs need access to

financing for basic business development in normal times. They may also need access to disaster risk financing to cope with devastating disaster losses, but risk financing alone will not ensure their long-term business continuity. Many aspects of SME disaster resilience are an interaction between the underlying economic health of the enterprise, and measures taken to reduce disaster risk and manage disaster shocks. This brings together two policy pillars that are present in Viet Nam, and indeed in most other ASEAN countries, but which rarely interact. The first is the policy framework to develop and promote SMEs as business enterprises. The second is the national framework for ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ or DRM, along with the framework for climate change adaptation (CCA).

The purpose of the report is to identify the main disaster risks for SMEs in Viet Nam, to report on the SME Resilience Survey findings, and then consider aspects of the enabling environment for SME disaster resilience that are working well, areas that could be enhanced through stronger policy support or resources, and new approaches that might be considered as part of a Viet Nam road map for SME disaster resilience. It is based on:

xii ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

1

desk research on laws, policies and secondary resources

an SME survey undertaken by ADPC and partners in Viet Nam in late 2015; and

a country mission by the international consultant in January 2016 that included discussions with partners and other stakeholders concerning implementation of policy responsibilities, government, private sector and NGO initiatives.

This report is just one part of a government and stakeholder process towards developing a roadmap for increasing Vietnamese SMEs’ resilience to disasters. It is also part of a much broader regional project being implemented by the iPrepare Business facility, called “Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Small and Medium Enterprises in Asia Project,” (the Regional Project), which includes Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. The project aims to build disaster-resilient enterprises by: 1) identifying actions to strengthen resilience of SMEs; 2) providing technical assistance in strengthening resilience to selected SMEs on a demand-driven basis; 3) supporting governments in strengthening the enabling environment that promotes risk-sensitive and informed investments by SMEs; and 4)

facilitating knowledge sharing at the regional level.

A key component of the regional project is an SME survey in each project country of SME perception of risk, disaster experience, preparedness for likely hazard events, and business continuity planning for disaster risk reduction and recovery. The learning from the country policy analyses and SME surveys were shared in a regional forum in April 2016, which now feeds into a national roadmap process for SME disaster resilience in each project country. Finally, a project synthesis report later in 2016 will bring together the project findings as a regional resource.

In Viet Nam, the iPrepare Business facility is working with a government partner, the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI), in particular the Agency for Enterprise Development and The Assistance Center for SME-North Viet Nam (TAC-Hanoi).The Regional Project is supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) Integrated Disaster Risk Management Fund (IDRM Fund), which in turn is financed by the Government of Canada, and the German Ministry for Economic Development and Cooperation (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) within the framework of the Global Initiative on Disaster Risk Management (GIDRM).

SMEs play a vital role in all the ASEAN economies, making up the vast majority of enterprises (between

88.8 and 99.9 percent), and contributing significantly to national employment (between 51.7 and 97.2 percent), across all economic sectors and in both rural and urban areas.3 They also provide significant economic opportunities for women and youth, and account for a substantial slice of GDP, between about 30-35 percent on average.4 In contrast to their numbers and share of employment, however, their share of total exports remains small, at between 10.0 and 29.9 percent,5 and they have thus been identified as requiring additional

3 ASEAN. 2015. “ASEAN Strategic Action Plan for SME Development 2016-2025”. P.1. (In fact these ASEAN figures refer to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) – but for these purposes MSMEs are equated with SMEs.)

4 Narjoko, Dionisius. 2014. “Turning Dream Into Reality? Achieving the Goal of Small and Medium Enterprise Development in ASEAN Economic Community.” Taipei: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

5 ASEAN. 2015. P.1.

Towards Disaster-Resilient SMEs

support for development and promotion. Regional policy support for SMEs through APEC, ASEAN and other organizations will be considered in a regional project synthesis report to be completed later in 2016.

In addition to purely economic and business challenges, SMEs in Southeast Asia also face business disruption, economic loss and sometimes complete closure as a result of the impacts of natural hazards, such as floods and storms. In countries such as Viet Nam, which has a long coastline where much economic activity occurs, the threat of sea-level rise due to climate change is also a very real one that needs to be addressed well in advance. Hence this report aims to identify some of the best ways to support Viet Nam’s SMEs to become more disaster resilient, to both sudden-onset events such as floods and storms, as well as slow-onset stresses such as drought (a temporary situation) and sea-level rise (a permanent change).

01

TOwARdS diSASTER-RESiLiENT SMES 3

What is disaster resilience?

The concept of resilience is used extensively in this report and deserves a brief explanation. A useful definition is that resilience is:

The ability of a system and its component parts to anticipate, absorb, accommodate, or recover from the effects of a hazardous event in a timely and efficient manner, including through ensuring the preservation, restoration, or improvement of its essential basic structures and functions6

A disaster-resilient enterprise is therefore one that has the capacity to survive and recover from a disaster that affects it, in a way that enables it to continue to grow and develop, and even improve. Obviously this includes not suffering such huge losses that the enterprise ceases operation, but it also relates to smaller shocks and stresses that can affect the long-term viability and growth of an enterprise. But the fact that this definition talks about systems and their component parts is also a reminder that SMEs are not simply a number of independent entities; they are part of international, national and local systems of commerce and trade, finance and insurance that are governed by laws, policies and institutions. Therefore their resilience is partly determined by their own capacities and partly by the business environment in which they work.

It should also be noted that although the word ‘disaster’ is widely used to refer to large-scale natural hazards, when used in the context of disaster risk management, it refers not to the hazards themselves, but to the effect that they have on communities, including SMEs. A widely accepted definition of disaster is:

6 IPCC. 2012: “Glossary of terms. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation.” Available at http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/srex/SREX-Annex_Glossary.pdf

A serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.7

Thus, the disaster risk of SMEs is partly determined by their actual exposure to natural hazards, and partly by their capacity to reduce the risks through taking preventive action and developing better coping capacities. So a key part of becoming disaster-resilient is the idea of disaster risk reduction (DRR),8 as resilience includes the ability to anticipate and prepare for foreseeable hazards so that they do not become disasters. It includes actions to prevent hazards occurring where possible, to reduce physical exposure to them based on business location, and to reduce vulnerability by taking protective and preventive measures to mitigate the effects of hazards. It also means having the capacity to cope with disasters when they occur, through preparedness and effective emergency response, including contingency plans, as well as access to post-disaster mechanisms to support full recovery. Thus, disaster-resilience for SMEs is not just about how they respond to hazards and recover from disasters, it is also about SMEs assessing their underlying disaster risks and reducing them to an acceptable level, as part of business continuity management (BCM).

The aim of the regional project is to address, so far as possible, the full range of physical hazards and their consequences that SMEs are likely to face, and which may affect their development, profitability or survival.

Although the title of Viet Nam’s law on disaster risk management is usually translated as The Law on Natural Disaster Prevention and Control 2013

7 The following terms are defined according to UNISDR Terminology 2009, available at http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology: disaster risk reduction, emergency response, exposure, mitigation, preparedness, recovery, vulnerability.

8 The italicized words in this paragraph are commonly used terms in the field of DRM. Definitions are found in the UNISDR Terminology 2009 (undergoing review from August 2015), at http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology

01

(No. 33/2013/QH13) (“Law on NDPC”), and the law in fact considers only the risk from natural phenomena, the terms ‘hazard’ and ‘disaster’ are not generally restricted to natural phenomena and their effects. Hence, the above definition of disasters also encompasses technological or human-made hazards, especially as these often compound the effects of natural events to create mixed hazards that result in worse disasters. For example, flooding may result in the spread of dangerous pollutants if industrial or agricultural premises have not adequately protected chemical supplies from floodwaters.

Analysis of SME disaster risk also needs to consider the extent to which potential long-term changes in disaster risk as a consequence of climate change are taken into account, both by SMEs themselves and by government policies intended to support SME resilience and development. Thus, the terms ‘disaster risk’ and ‘climate and disaster risk’ are both used in this report to describe the natural and human-made hazards that SMEs need to consider, while noting that climate risk alone does not describe all relevant natural hazards (e.g. earthquakes).

Characterizing SME disaster risk in the policy context

The underlying question of this report is how policy interventions can promote and support SMEs to attain disaster resilience. In this regard it is therefore helpful to divide the disaster risks faced by SMEs into two broad categories: (1) shared community disaster risks and (2) business continuity disaster risks.

1. Shared community disaster risks

SMEs, even more so than large enterprises, are physically embedded in urban and rural communities (although some are now part of industrial estates and special economic zones). This means that their exposure to natural and other large-scale local hazards is, by and large, the same as that of the communities in which they

operate. Thus, many aspects of promoting disaster resilience for SMEs can be done through the same policy tools as are used for the general population. The main such tools are the national and local DRM systems, known in Viet Nam as ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ (NDPC), made up of the laws, policies and institutions addressing disaster risk management. In this report the system of laws, policies and institutions addressing climate change adaptation is also considered a part of the system of risk management against natural hazards, albeit in this case permanent changes to which SMEs, their communities and government frameworks need to adapt.

As will be seen, SMEs in Viet Nam tend to be micro and small enterprises that are very much part of their local communities. Owners and employees therefore need to be aware of the hazards in their locality and how to reduce their risk from them. This may include SME participation in local disaster risk assessments, community based disaster risk reduction programmes, or public awareness campaigns on local risks that are targeted to or inclusive of SMEs. SMEs may need to participate actively in early warnings systems, or opt in to a system to ensure they receive such warnings.

In addition to the major natural hazards of flood and storm, disaster preparation for SMEs also needs to include fire, earthquake (where relevant) and other emergency drills as necessary, to ensure employees’ safety in the face of all likely hazards. Preparation may also need to include contingency plans to move stock and/or plant and equipment to a safe location in the event of flood or storm warnings.

Many of these are the same measures as are needed for the surrounding community, and micro enterprises operating in community hubs may be well served by broad community based disaster risk management (CBDRM). However, small and medium enterprises, especially those situated outside settlements, may not always be regarded as part of the ‘community’ for such purposes, and yet may also not be part of industry organizations that focus on larger enterprises. It cannot be assumed that SMEs have access to the relevant information or expertise on disaster risk reduction

4 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

TOwARdS diSASTER-RESiLiENT SMES 5

and emergency response, so efforts may need to be made to include them in community level risk reduction, preparedness, response and recovery.

This concern was borne out by a 2011 in-depth survey in three provinces of Viet Nam (Nghe An, Da Nang and Khanh Hoa), which indicated that, despite experiencing frequent and devastating natural hazards, the vast majority of businesses surveyed had not accessed any of the local authorities’ information on disaster preparedness, nor worked actively with local governments to get concrete guidance and plans in times of disaster.9 This was one of the questions tackled in the 2015 ADPC SME Resilience Survey, discussed in Part 3.

2. Business Continuity Disaster Risks

In addition to shared community disaster risks, SMEs may have particular vulnerabilities due to their industrial sector, type of activities or enterprise characteristics, as well as the nature of their supply chains and markets.10 These can be described as business continuity disaster risks. For example, the agricultural sector can suffer losses due to drought, late arrival of the monsoon, or crop pests, which have little effect on the communities where they are based. Small retail businesses may lose uninsured stock due to floods or fires, an economic impact lasting well beyond the hazard itself, or they could face loss of business due to prolonged power cuts caused by emergencies elsewhere. Many businesses may face major disruptions if road access is blocked or roads washed away, affecting their ability to receive supplies and take produce or merchandise to markets; and in manufacturing they may have difficulty obtaining raw materials

9 USAID (United States Agency for International Development), TAF (The Asia Foundation), CED (Center for Education and Development) and VCCI (Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry). 2011. “Assessment of Disaster Preparation by Vietnamese SMEs.” (Executive Summary, English). USAID, TAF, CED, VCCI: Hanoi, p. 12.

10 There are now many resources available on these questions. Starting points include two special journal editions: ADPC. 2014. “Engaging the Private Sector in Disaster Risk Reduction”, Special Edition, Asian Disaster Management News, June 2014. P 52-54. Bangkok, Thailand: ADPC; and APEC-ACMC (SME Crisis Management Center). 2014. APEC SME Monitor, Issue 16, June 2014. Taipei, Taiwan: APEC-SCMC [special edition on MSE business continuity planning in the face of disasters].

or parts if their own suppliers are devastated by a disaster.

The very fact of being business enterprises makes SMEs vulnerable to different types of economic loss and damage, even from hazards that also affect their local communities. Not only do they risk losing goods and assets, as do residents, but both owners and employees face the risk of short or long term loss of employment/income if a disaster seriously disrupts their ability to operate in their normal premises (e.g. due to flooding or blocked physical access, loss of communications, disrupted water or electricity supply), or if it negatively impacts their supply chains, distribution or service networks, or demand for their goods or services in a disaster-affected area. Loss of SMEs from a community following a disaster also impacts livelihoods and prosperity in the wider community.

These business continuity disaster risks arise from the same types of hazard as shared community risks, but they are not necessarily restricted to the immediate locality. Hazards that cause disasters in other areas can also affect SME supply chains or distribution networks. Preparation for such eventualities requires a more business-oriented approach to risk assessment and contingency planning.

Policy approaches to support resilience through business continuity management are likely to be the most effective for disaster risks related to the particular disaster vulnerabilities of business activities, in particular supply chain issues... For this reason the policy tools used to encourage SME development and to support their broader economic resilience may be the best starting points to support SME business continuity management (BCM) and especially the development and implementation of business continuity plans (BCP) that enhance disaster resilience.11 Other mechanism such as BCM capacity building, tax concessions, access to finance and general reform of the business environment can also support disaster resilience. These systems are aimed at business support, and such systems also have multiple entry points to access SMEs to provide information about disaster risk and to

11 As discussed in Part 5.

provide incentives for SMEs to become disaster-resilient. However, while such frameworks focus on SME economic wellbeing, they can sometimes fail to take account of SME economic losses from disasters, or the reasons for such losses, including the extent to which these are preventable through DRR, contingency planning and disaster recovery support.

This categorization of SME risks leads to two guiding questions for the Viet Nam country policy analysis, due to the possibility that SME disaster resilience may fall between two pillars:

1. To what extent do the climate change adaptation and ‘natural disaster prevention and control’ systems either include SME representatives at national level, or integrate SMEs into local institutions, risk awareness campaigns, emergency response and recovery operations at local level?

2. To what extent is climate and disaster resilience factored into the picture of an economically healthy SME through policy schemes targeted at SME development and promotion?

6 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

Vietnamese law defines SMEs according to criteria set out in Decree 56/2009/ND-CP (Decree

56) on Support for Development of SMEs.12

Under Decree 56, SMEs are defined as registered establishments and divided into the following sub-categories: very small (also often described as micro), small, and medium, according to the size of their total capital (equivalent to the total assets identified in an enterprise’s accounting balance sheet) or the average annual number of employees. Total capital is the key criterion.

Viet Nam’s categorisation of enterprises as SMEs is complex, because of the nature of the business assets test and the way national statistics are tabulated. Statistical analysis of enterprises based on the SME

12 This replaced the single definition of an SME in Decree 90/2001/ND-CP of 2001 - as a business with registered capital up to 10 billion VND or up to 300 employees.

size criteria is not always readily available, or must be interpolated from other figures. In Viet Nam, for most statistical purposes, the General Statistics office (GSO) primarily reports on enterprises under the following categories: State-owned Enterprises (SOEs), Private Sector Enterprises, Foreign Invested Enterprises (FIEs), Cooperatives (often translated as collectives), and non-farm Household Business (HHB). HHB’s are defined in law as single premises businesses operated by one person or household, with up to 10 employees, and every adult has the right to establish such a business.13 They thus fit within the category of very small or micro enterprises as far as employee numbers are concerned. However, the above definition also refers to registered businesses, and not all HHB’s need to register. Those engaged in agriculture, forestry, fishing or salt production, or who are low-income traders (street vendors, long-distance or itinerant

13 Decree N°88 of 29/08/2006 on Business Registration, Articles 36,37.

02SMEs in Viet Nam –

characteristics and risks

Figure 1 Legal definition of very small (micro), small and medium enterprises in Viet Nam under Decree 56

Enterprise size Very small enterprises

Small-sized enterprises Medium-sized enterprises

Number of labourers

Total capital Number of labourers

Total capital Number of labourers

Agriculture, forestry & fishery

10 persons or fewer

VND 20 billion or less

Between over 10 persons & 200 persons

Between over VND 20 billion & VND 100 billion

Between over 200 persons and 300 persons

Industry & construction

10 persons or fewer

VND 20 billion or less

Between over 10 persons & 200 persons

Between over VND 20 billion & VND 100 billion

Between over 200 persons and 300 persons

Trade & service 10 persons or fewer

VND 10 billion or less

Between over 10 persons & 50 persons

Between over VND 10 billion & VND 50 billion

Between over 50 persons and 100 persons

Table graphic by Business-in-Asia.com 2016.

traders), are not required to register unless they have more than 10 employees.14 Thus, the aggregate statistics on SMEs will generally reflect only the non-farm HHBs, and not the HHBs that are primary producers or low-income traders. And yet the HHB sector as a whole remains an extremely important part of the national economy.

Based on the employee-numbers criteria only, and including all forms of ownership (Figure 2 below), in 2013 there were 368,844 registered enterprises in Viet Nam, of which 70% were micro, 26% small, 1.9% medium and 2.1% large. SMEs thus accounted for 97.9% of all enterprises in Viet Nam. Even the formal economy is thus dominated by small and medium enterprises.

As noted in Figure 2, in 2013 the SME sector consisted of:

state-owned enterprises (0.86% of total active MSMEs),

private enterprises (97.42%), and

14 Art. 40 CMPI Circular 54435-01-2013-TT-BKHDT.

foreign-invested enterprises (2.72%).

The vast majority of enterprises are thus privately owned. However, it should also be noted that the public sector enterprises are mostly large or medium, and that the vast majority of the smaller businesses are private sector - with 99% of all micros and almost 94% of all small enterprises being privately owned.15 As the Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) has pointed out, this is ‘a point to be noted by policy makers in order to provide more appropriate support for micro and small enterprises.’16

VCCI has also undertaken an analysis of the consistency of the Decree 56 labor-force criteria and the assets criteria in categorizing enterprises by size. This indicates that at the two ends of the spectrum these criteria give consistent results, in that most enterprises with a small capital size also have small or micro employee numbers, and those with large capital size also have large labor forces.17 But there is something of a mismatch in

15 VCCI. 2014. Vietnam Business Annual Report 2014 p.30. Actual figure for small is 93.77% privately owned.

16 Ibid.17 VCCI. 2014. P. 32.

8 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

SMES iN ViET NAM – ChARACTERiSTiCS ANd RiSkS 9

technology, accommodation, and food services) at 20.5%; and manufacturing at almost 16%.18

SMEs employ almost 47% of the total workforce (5.1 million workers in 2012), and that number is increasing. Most of the SME employment is in labor-intensive industries, such as manufacturing (almost 32% of total SME employees) and construction (almost 24%), while wholesale and retail trade accounts for almost 22% and the service sector 13% of total SME employees. The total net income of SMEs was D 5,033 trillion in 2012 (approximately USD 225 billion), a growth of 7.7% from 2011, but the growth of profits in the overall SME sector has been slowing since 2009.19

SMEs are clearly the economic backbone of Viet Nam, and their development has received policy

18 ADB.2015. Asia SME Finance Monitor 2014. p. 239.19 Ibid.

the medium enterprise categories, as 92.78% of those with medium capital actually have a micro size labor force, and up to 44.7% of those with medium labor force size actually have large capital size. This suggests that, at least for certain types of enterprises, the labor force is very low compared with the capital investment required for operation. This appears to require some fine-tuning of the business size criteria, if policy initiatives are to be well targeted.

SMEs in Viet Nam’s Economy

The dominant industry group amongst SMEs is wholesale and retail trade, which accounts for almost 40%; then the service sector (including

Figure 2 Classification of enterprises based on size of labor force and form of business ownership 2013

Form of ownershipTotal

State Private FDI

Micro

Number (Enterprises) 112 255,747 2,462 258,321

By rows (%) 0.04 99.01 0.95

By columns (%) 3.53 71.91 24.59 70.04

Small

Number (Enterprises) 1.257 89,622 4,694 95,573

By rows (%) 1.32 93.77 4.91

By columns (%) 39.57 25.20 46.87 25.91

Medium

Number (Enterprises) 504 5,653 830 6,987

By rows (%) 7.21 80.91 11.88

By columns (%) 15.86 1.59 8.29 1.89

Large

Number (Enterprises) 1,304 4,631 2,028 7,963

By rows (%) 16.38 58.15 25.47

By columns (%) 41.04 1.30 20.25 2.16

TotalNumber (Enterprises) 3,177 355,653 10,014 368,844

Proportion (%) 0.86 96.42 2.72

Source: VCCI. 2014. Viet Nam Business Annual Report 2014. Based on GSO 2014 business survey.

economic sectors – predominantly located on coastal plains and river deltas, the country has been identified by the World Bank as highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.21

The National Strategy on Climate Change is also notes, for example, that the Mekong Delta is one of the world’s three most vulnerable deltas to sea-level rise and that a projected 1 meter sea-level rise by the late 21st century would affect 40% of that delta (the country’s ‘rice bowl’), 11% of the Red River Delta, and inundate 3% of coastal provinces (including 20% of Ho Chi Minh City). Such a rise would affect 10-12% of the population and decrease GDP by around 10% - unless primary production and business is able to plan and adapt in advance.

21 GFDRR. 2011.”Vietnam: Vulnerability, Risk Reduction and Adaptation to Climate Change.” World Bank. P.14. http://sdwebx.worldbank.org/climateportalb/doc/GFDRRCountryProfiles/wb_gfdrr_climate_change_country_profile_for_VNM.pdf

priority for some years. However, in addition to business development issues and economic environment impacts, SMEs in Viet Nam also experience disruptions from both natural and human-made hazards.

SME Disaster and Climate Risk in Viet Nam

The main natural hazards Viet Nam faces are floods tropical cyclones, and drought. In terms of future risk, there is also concern that these hazards will become more extreme with climate change, and that the country’s long coastline and river deltas will be very vulnerable to sea level rise.20 In fact, with industry and agriculture – its two most important

20 CE-DMHA. 2015.Vietnam Disaster Management Reference Handbook. Hawaii: US DoD. Pp. 26-33.

Figure 3 Number of SMEs in Viet Nam 2007-2013(R

p Bi

l.)

400,000 97.7

5.3

100

80

60

40

20

Perc

enta

ge

350,000

300,000

250,000

200,000

150,000

100,000

50,000

0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

MSMEs (Number) MSME to total (%) Trade MSME growth (%) Manufacturing (% share)

Service (% share) Construction (% share) Others (% share) Primary industry (% share)

Data include micro enterprises. Primary industry includes agriculture, forestry & fisheries.

Source: ADB. 2015. Asia SME Finance Monitor 2014 (based on MPI 2012 data).

10 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

SMES iN ViET NAM – ChARACTERiSTiCS ANd RiSkS 11

SMEs in Viet Nam tend not to be based in separate industrial parks or zones, and as such they largely share the surrounding community’s physical exposure to hazards and the same immediate dangers to personnel. So although they have additional business continuity risks from disasters, these shared community disaster risks need to play a significant role in their risk assessments for business continuity management (BCM), as these risks are largely based on exposure by location or geographical area, coupled with the effectiveness of the community’s efforts in disaster risk reduction, preparedness, and emergency response, which can all reduce damage and loss. SME strategies for managing disaster risk should therefore place an emphasis on engagement with and understanding of local disaster prevention and control mechanisms.

As the geographical location of an SME will often determine its initial hazard risk (exposure), adequate BCM often needs to be underpinned by local area risk mapping. National statistics on SME locations can potentially be matched with national and local risk mapping data, to indicate priority areas for capacity building and BCM initiatives for SME disaster resilience, if this data is available.

Retail and service sector enterprises, by their nature, tend to be embedded within their communities, and primarily serve local clients. For many of them, their immediate disaster risk will also be very localized, or shared community disaster risks, in addition to supply chain issues and customer

access. However, SMEs in manufacturing are more likely to be physically separate from residential and light commercial areas in settlements, even if they are not in separate industrial parks, so they may need to have more specifically targeted initiatives on disaster risk assessments and resilience, even within Viet Nam’s system for ‘natural disaster prevention and control’.

SMEs in manufacturing, retail and wholesale trade, are also likely to be affected significantly by supply chain and distribution blockages originating from disasters in both their own and other areas. Similarly for those in the tourist service sector, if tourists are unable to access their facilities due to travel restrictions or breakdown in services as a consequence of a disaster in another other locality. There are specific vulnerabilities in business continuity that can affect enterprises reliant on remote supply chain and distribution networks, and/or on movement of clients from other countries or other parts of Viet Nam. Of course local supply and distribution networks are also disrupted by local disasters, and these threats to business continuity need to be part of BCM and other contingency planning.

The survey group

The survey was conducted by an independent firm using the SME contact lists of country partner TAC-Hanoi (via post and email), as well as being administered to participants in TAC-

Figure 4 The relative frequency of natural hazards in Viet Nam

High Medium Low

FloodTyphoonCycloneFlash floodTornadoLightningDrought

RainHailLandslideSalinityIntrusion

EarthquakeFrost

Hanoi SME training events. There were 442 respondents, a significant sample size, albeit small in comparison with 360,000 plus SMEs in Viet Nam. Annex 1 provides further details of the sample group and survey methodology.

The majority of the SMEs surveyed were micro or small. They were also mainly young private enterprises, and the vast majority were owned by men:

The respondents came from a range of sectors and from across the nation.

39% of the respondents reported 1 to 9 employees (micro, subject to assets test) and over 50% of the respondents had 9 to 99 employees (small, subject to assets test);

76% of the surveyed SMEs reported a total asset value less than 10 billion Viet Nam Dong (micro), 12 % had total asset value of between 10 and 20 billion Viet Nam Dong (small), and only 2% of them

had total assets valued over 100 billion Viet Nam Dong (medium);

Over 62% of the total respondents reported that their enterprises were established in the previous 6 years, between 2009 and 2015;

There was a marked gender difference in business ownership, with 71% percent reporting they were owned by men and 27% by women (2% no replies). Currently there are no national statistics published on gender of SME owners to compare with the survey sample;

Most of the respondents reporting they were individual privately owned enterprises; and

Only 7% reported premises located in an industrial/economic zone.

While Annex 1 provides more detail, it is worth noting some of the survey group

How disaster-resilient are SMEs?

– The SME Survey

03

hOw diSASTER-RESiLiENT ARE SMES? – ThE SME SURVEy 13

03

characteristics in more detail at this point in order to understand how the survey results relate to SME policy. Figure 5 (below) shows the sectoral distribution, with 41% from wholesale and retail trade, 17% from construction, while ‘others’ accounted for 26% (this refers to companies that fit within more than listed sector, or whose business type is not listed; the size of this group indicates that many of the respondents did not identify as clearly falling within one of the recognized business sectors used for statistical collection in Viet Nam). None of the remaining sectors accounted for more than 5%. No directly comparable published statistics were identified for SMEs, although across Viet Nam’s enterprises as a whole, almost 70% are in commerce and services, just over 30% in construction, and just under 1% in the agricultural sector.22

Figure 6 shows that most of the surveyed SMEs reported fewer than 100 employees, classifying them as either micro or small according to the definitions of SMEs under Government of Viet Nam Decree No. 56/2009/NĐ-CP on supporting SMEs.

39% were micro enterprises, reporting fewer than 10 employees;

22 VCCI. 2015. Vietnam Business Annual Report 2014. p. 38

over 51% were small enterprises, reporting between 10 -100 employees;

6% were medium, reporting 100 - 200 employees; and

4% were large, reporting over 200 employees.

Figure 6: Distribution of respondents according to number of employees

In terms of asset value criteria for size, the results were similar to those based on number of employees:

76% reported a total asset value of less than 10 billion Viet Nam Dong;

12 % reported a total asset value from 10 to 20 billion Viet Nam Dong; and

only 2% of them reported a total asset value over 100 billion Viet Nam Dong.

Decree No.56/2009 defines SMEs differently in different sectors. For the wholesale and retail trade sector, micros become small enterprises when they have a total capital value of 10 billion VND, whereas the threshold is more than 20 billion VND of total capital for other sectors. The total capital equivalent

Figure 5 Distribution by major industry sectors

Wholesale & retail trade 41 %

Others 26 %

Construction 17 %

Industry & quarrying 5 %

Agriculture, forestry & fishery 4 %

Transportation & storage 2 %

Accommodation service activities Food service activities 2 %

0 20 % 40 % 60 % 80 % 100 %

to total assets is determined by the balance sheet of the enterprise.

Findings on Risk Exposure and Impacts of Previous Disasters

Figure 7 shows the results of a question asking respondents to choose the top 3 hazards they believed would have the potential to disrupt their business operations. The top 5 choices were: power blackouts (listed by 41%), regional/global economic crises (40%), fire (35%), typhoon (32%) and flood (21%).

However, when asked to consider the hazards that caused actual disruptions, 399 out of 442 (more than 90%) of the respondents responded that they had never experienced a business operation disruption due to disasters. Of those who had experienced business disruption, 36 respondents reported this was mainly due to human made

hazards such as foreign currency fluctuation, regional/global economic crises, power blackouts, and accident, and only 2 respondents said this had occurred due to flood. This can be accounted for by the fact that most of the respondents were young SMEs that had started since 2009, and as it happens Viet Nam has not experienced any severe natural events during that time. However, even during that period there has been an increase in urban flooding, so this result could reflect the geographical location of respondents and/or different perceptions about what is meant by a ‘major disruption’ to business.

Although the proportion reporting business disruptions due to hazards was low, the main disruptions that were experienced included the inability of employees to go to work, not being able to deliver products to customers, damages to facilities, equipment and raw materials, and delayed deliveries from suppliers.

Figure 6 Distribution of respondents according to number of employees

39 %

6 %

2 %2 %

51 %

1-9 persons

10-99 persons

100-199 persons

200-300 persons

> 300 persons

14 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

hOw diSASTER-RESiLiENT ARE SMES? – ThE SME SURVEy 15

Figure 7 Hazards that can potentially affect business operations by the respondents

Power blackout 41 %

Regional or global economic crisis 40 %

Fire 35 %

Typhoon 32 %

Accidents 31 %

Data loss 30 %

Foreign currency fluctuations 30 %

Civil unrest 27 %

Flood 21 %

Transportation system breakdown 18 %

Earthquake 16 %

Theft 16 %

Disease 13 %

Water shortage or contamination 11 %

Cyber attacks 11 %

Lightning 8 %

Tornado 8 %

Landslide 7 %

Terrorism 7 %

Drought 6 %

Tsunami 5 %

Pandemic/Epidemic 5 %

Wildfire 2 %

Insect infestation 1 %

None 2 %

0 10 % 20 % 30 % 40 % 50 %

Findings on Business Continuity Plan Adoption

In response to the question of whether they have developed a BCP (or similar) to ensure their business survives the types of hazards and shocks they are likely to experience in their localities and type of business:23

almost 80% of the respondents indicated they did not have written a BCP

14% confirmed that they are in the process of preparing a BCP

4.5% responded they already had a BCP

Within the 4.5% with a written BCP, 15% of them were small, 35% were medium, and 45% of them were micro enterprises (based on the definition of SMEs under Decree No.56/2009).

From responses by the surveyed SMEs, it can be seen that almost all the SMEs with a BCPs had developed them based on self-searching information on the internet, or due to help from NGOs.

For those without a BCP, the top 3 reasons for not preparing one were: they had not heard of BCP before (52%); they lacked a budget for preparing a BCP (40%); and they lacked of information on how to prepare a BCP (30%), (see Figure 8).

23 BCP is not an established term in Vietnamese. Although it was not defined separately, the phrase used in the Vietnamese language survey questionnaire described a plan to support SMEs to be able to continue/maintain their business: KẾ HOẾCH DUY TRÌ HOẾT ĐẾNG KINH DOANH.

In responding to the question on their top 3 motivations for developing their BCPs, those with BCPs said the main reasons were: to protect employees (33% listed in their top three reasons); to avoid economic losses (32%); to enhance their reputation (22%); respondents believed BCP is a good business practice (19%); they thought BCP would help them gain a competitive advantage (19%); and 14% thought it is needed for those enterprises located in disaster prone areas. Around 7% of respondent SMEs said they do not know the reason why they needed to have a BCP for their businesses, (see Figure 9).

Findings on Incentives and Training Needs

Figure 10 shows that more than 40% of respondents felt that the government should make it compulsory for SMEs to prepare a BCP to avoid or reduce the impacts of disasters, while 28% said no, and 17% did not know. Those who replied that BCP should not be compulsory believed that the government should help the SMEs increase their awareness on BCP and its benefits and then let the SMEs choose whether or not to have a BCP, but that the government should not force SMEs to have BCP at this stage.

In reply to the question what are their preferred three types of incentives that the government should provide to SMEs to encourage them to be disaster resilience, surveyed SMEs responded as follows:

Figure 8 Top 3 reasons for not preparing a BCP so far

had not heard of BCP before 52%

Lack any budget for preparing a BCP 40%

Lack information on how to prepare a BCP 30%

0 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

16 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

hOw diSASTER-RESiLiENT ARE SMES? – ThE SME SURVEy 17

61% listed tax credits, deductions, and exemptions for SMEs with a BCP in their top three incentives

53% selected subsidies, grants, and soft loans for the preparation of a Business Continuity Plan

15% nominated certification schemes (e.g., certified SMEs will be preferred suppliers)

19% listed awards and recognition for disaster resilient SMEs

35% said there was a need for provision of technical assistance, consultancy service, or training in BCP preparation and disaster preparedness

29% thought legislation, policies, and institutional arrangements that encourage SME participation in disaster risk management would be effective (e.g., membership in local DRM councils and committees); and

Figure 11 shows that more than 90% of the respondents confirmed their enterprises had not attended any training related to BCP, and 5% said they had (the remainder 5% did not answer).

Similar to BCP training, 88% of the respondents confirmed that they have never participated in a training related to disaster risk management (disaster prevention, hazard mitigation, disaster preparedness, emergency response, disaster recovery, etc.), 7% said yes and the remaining 5% with no answer as shown in Figure 12.

Findings on disaster preparedness

327 out of 442 respondents (74%) answered that they were not participating in a Local Flood and Storm Control Committee, while a significant minority of 89 respondents (20%) said yes they were (6% no answer).

There were similar responses to the question of whether their SMEs had established a mutual aid agreement with another organization to help each other during and after emergencies (examples given were privately-run emergency teams, fire brigades, search and rescue teams, mutual help associations, etc.). Almost 70% of the respondents answered with no and less than 20% with yes (10% no answer).

Figure 9 Motivations for SMEs that had developed BCPs

To protect employees 33 %

To avoid economic loss 32 %

To create a good reputation 22 %

BCP is a good practice 19 %

To create a competitive advantage 19 %

Is needed for enterprises located in the disaster prone areas 14 %

Do not know 7 %

0 10 % 20 % 30 % 40 % 50 %

Figure 10 Whether BCP should be compulsory

42 %

28 %

17 %

13 %

yes

No

do not know

No answer

Figure 11 Attendance at BCP-related training

90 %

5 % 5 %

Not yet

yes

No answer

18 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

hOw diSASTER-RESiLiENT ARE SMES? – ThE SME SURVEy 19

174 out of 442 respondents (almost 40%) had no written disaster preparedness plans for their business protection, 129 respondents had emergency response plans, 79 respondents had evacuation plans, and 107 respondents had emergency communications plans. Regarding system down manuals, system recovery manuals, risk assessment and risk reduction measures, less than 10% of the respondents confirmed that they have them for their businesses.

The top 4 coping mechanisms that respondents reported using in dealing with business disruptions and emergencies were (i) using their own savings (209/442); (ii) accessing support from family and friends (177/442); (iii) using bank loans with interest (168/442); and (iv) reducing expenses (159/442). 105 respondents confirmed that they claimed insurance when facing with business disruption or emergency cases. However, only 13 out of these 105 had natural catastrophe insurance cover, only 13 out of these 105 chose natural catastrophic insurance, the rest were using other insurance products such as insurance for employees, fire insurance and motor/car insurance.

Figure 12 Attendance at disaster risk management-related training

88 %

5 %7 %

Not yet

yes

No answer

Figure 12 shows that 347 out of 442 (almost 80%) of respondents confirmed that they would like to participate in activities to support SMEs in Viet Nam to enhance their resilience from hazards and disasters, 15% said no and 6% gave no answer for this question.

Findings on financial coping mechanisms

The top 3 disaster risk financing mechanisms that respondent SMEs reported they currently have were: insurance for employees (261 out of 442 or equivalent to 59%); fire insurance (172 out of 442 or 39%); and motor/car insurance (149 out of 442 or 34%). These types of insurance are generally compulsory by law, so this result could reflect either a lack of compliance and/or a lack of precise knowledge about enterprise insurance policies by the individual respondents. In addition, 60 out of 442 - almost 14% - responded that they are using natural catastrophe insurance for their businesses. However, when responding to the question of what

are their main coping mechanisms for dealing with business disruptions and emergencies, only 13 out of these 60 chose as one of their top three options ‘by claiming insurance’. It seems possible that many respondents did not understand one of these two questions, or else that they do not yet have experience of claiming insurance, as natural catastrophe insurance is still a new concept in Viet Nam (and is not compulsory by law) and recent years have seen few major natural hazards in the country. This finding also most likely reflects limited financial literacy and low trust in insurance products amongst SMEs in Viet Nam.

Survey overview and conclusions

A large portion of the respondents (around 90%) were micro and small enterprises, which were mainly privately owned businesses that were not located in any industrial park or economic zone (presumably meaning they are located within communities). These types of enterprises are less likely to have large building structures or

mitigation works in place to physically protect them from hazards, and normally have few financial reserves or access to risk financing to help their recovery after a severe disaster. As a result they need more support from the government and other organizations to help them build resilient businesses.

SMEs in Viet Nam have to deal with both natural and human-made hazards. In terms of risk perception, actual experience influences the views of responders. In this sample many respondents had experienced different types of human-made hazards such as power blackout, regional/global economic crises, fires, etc. Natural hazards such as typhoon and flood were also there, but with lower experience and lower concern about their potential effects. This can be partly explained by the fact that most respondents were young enterprises set up since 2009, a period during which Viet Nam has not experienced any large or severe natural hazard events. However, as noted above, even during that period there has been an increase in urban flooding, so this could reflect the geographical location of respondents and/or different perceptions about what is a ‘major disruption.’ In fact, typhoons or/and

Figure 13 Willingness to participate in activities to support SMEs

79 %

6 %

15 %

yes

No

No answer

20 ENABLiNG ENViRONMENT & OPPORTUNiTiES • VIET NAM

hOw diSASTER-RESiLiENT ARE SMES? – ThE SME SURVEy 21

floods can also cause power failures, disruption of transport systems/networks and interruptions in communication systems, which were also identified as potential threats and as experienced hazards. Therefore, promoting disaster resilience for SMEs should build on frequently experienced hazards and also on raising understanding of related impacts of natural hazards in a changing climate.

In terms of impacts, disaster affects almost all aspects of business operations. Only around 10% of respondents reported disruptions due to hazards, but of these the main impacts were the inability of employees to go to work, not being able to deliver products to customers, damage to facilities, equipment and raw materials, and delayed deliveries from suppliers. In addition to the immediate effects on operations, most of these issues relate to supply chain security.

In terms of business ownership by gender, it can be seen from the survey results that women make up only 27% of owners. This may indicate a large gender imbalance in SME ownership, although the survey results represent a relatively small sample and need to be calibrated against national statistics. Currently there are no national statistics published on gender of SME owners. Nevertheless, this gender imbalance in the survey sample is surprising, given that World Bank statistics show that there is little gender difference in workforce