Victoria Electoral

Transcript of Victoria Electoral

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

1/15

Mlaga Economic Theory

Research Center

Working Papers

Indicators of Electoral Victory

Pablo Amoros and M. Socorro Puy

WP 2008-8

April 2008

Departamento de Teora e Historia EconmicaFacultad de Ciencias Econmicas y Empresariales

Universidad de Mlaga

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

2/15

Indicators of Electoral Victory

Pablo Amors and M. Socorro Puyy

Universidad de Mlaga

April 14, 2008

Abstract

We study a two-party contest where candidates strategically allo-cate their campaign resources between two salient issues. We analyzeto what extent the following indicators of a party success predict theelectoral victory: (1) the pre-campaign advantage, (2) the advantageon every salient issue, and (3) the advantage on campaign resources.We show that the electoral victory is guaranteed only when a partyhas a suciently large advantage on every salient issue. Otherwise

no combination of these indicators ensures the electoral victory.

Key-words: Election campaign, salient issues, majority voting.JEL classication numbers: D72, C70

A previous version of this paper was entitled A model of political campaign manip-ulation. The authors thank Enriqueta Aragons, Carmen Bevi, and Luis Corchn for

their helpful comments. Financial assistance from Ministerio de Educacin y Ciencia un-der project SEJ2005-04805, and Junta de Andaluca under project SEJ01645 is gratefullyacknowledged.

yCorresponding author: M. Socorro Puy, Dpto. Teora e Historia Econmica, Facultadde Econmicas. Campus El Ejido, Universidad de Mlaga, 29013, Mlaga, Spain. Fax:+34 95 213 1299. E-mail: [email protected]

1

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

3/15

1 Introduction

Political parties success indicators measure the chances that a party hasof achieving a majority on election. Having more chances of winning theelections is usually attributed to (1) the pre-campaign advantage, (2) the ad-vantage on every salient issue, and (3) the advantage on campaign resources.

In this paper we analyze from a theoretical viewpoint whether any of theseindicators predicts the electoral victory of a political party. We considera two-party, two-dimensional spatial model of political competition. Forthe duration of the political campaign, parties platforms have already beendecided. We follow the emphasis theory to describe parties competition inthe political campaign. The emphasis theory, as described by Page (1976),

argues that "political information is imperfect and there are limits on thenumber of messages that candidates can transmit or that the average votercan or will receive. Candidates must allocate their emphasis (in time, energy,and money) among policy stands and other sorts of campaign appeals". Asproposed by Page and formalized by Simon (2002) and Amors and Puy(2007), parties strategies for the duration of the political campaign aimat emphasizing the feature (in terms of issues) of the political party thatattracts more votes.1 In our model, parties campaign strategies consist ofemphasizing some political aspects more than other.

According to our model, the electorate can be partitioned into threegroups: partisan voters (those who will vote for one of the parties irrespec-tively of the parties campaign strategies), issue voters (those whose votedepend on the campaign strategies, and whom the parties aim at inuencingvia campaign expenditures), and abstention voters (those who are indierentbetween both political parties).

We show that the only indicator that can be used to predict the electoralvictory is the advantage on the salient issues. A suciently large advantageon every salient issue guarantees the electoral victory as far as it guaranteesthat a party has a majority of partisan voters. When no party has a majorityof partisan voters, the issue voters come into the scene and every kind ofmischief regarding the electoral results can occur. In particular, we nd

that a party may be majority-defeated in the elections even if it is the pre-campaign winner, has more campaign resources than its opponent, and has

1 Among others, Laver and Hunt (1992), Budge (1993), Riker (1993), Petrocik (1996),Simon (2002), and Sigelman and Buell (2004) show that there is empirical evidence ofcandidates emphasizing some issues more than others.

2

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

4/15

an advantage on every salient issue (as long as the sum of these advantages

is not too large).The later result is related to the literature on the Ostrogorskis paradox(Daudt and Rae 1976), originating from Ostrogorski (1902). This litera-ture postulates that the candidate with a majority on every single issue canbe majority-defeated in a representative democracy.2 We depart from theassumptions of this paradox in two main respects: voters preferences andparties behavior. While the Ostrogorskis paradox assumes that voters votefor the party with which they agree on more rather than fewer issues, weassume that voters preferences have intensities over issues and they vote forthe party that match their own ideal policy more accurately. Concerning thepolitical parties, while the Ostrogorskis paradox considers static parties, we

consider that parties behave strategically allocating emphasis across issues.The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the

model. Section 3 analyzes the success indicators. Section 4 provides theconclusions.

2 The model

There is a society with a nite set of voters, N=f1;:::;ng, which will selectby popular election a representative to serve in the legislature. There are twopolitical parties, Aand B , that compete for winning a majority of the votes

by spending campaign resources. There are two political issues, 1 and2.3Each partyj2 fA; Bg has a political position xj = (xj1; xj2)2[0; 1]2;

where xjr2[0; 1] is the political position of party j on issue r2 f1; 2g. Weassume that parties political positions are dierent on both issues: xA16=xB1 and xA26= xB2.4 Each party j is endowed with some xed campaignfunds cj 0. Campaign funds are devoted to the advertising campaign.A campaign strategyof party j is a vector cj2 Cj =f(cj1; cj2)2 R2+ :cj1 + cj2 cjg, which indicates how the party allocates its funds between

2 There are several posterior analyses that compare the results obtained in the electionsunder representative democracy and those obtained by majority voting in issue-by-issue

elections (e.g., Bezembinder and Van Acker, 1985, Kelly, 1989, and Laond and Lain,2006).3 The results of this paper can be generalized to the case ofm2 issues. For simplicity

of exposition we focus on the case of two issues.4 If the political positions of both parties on issue r are identical, then issue r becomes

innocuous according to the emphasis theory.

3

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

5/15

the two dierent issues. Let c= (cA; cB)2CA CB =Cdenote a prole ofcampaign strategies. For eachc2C and each r2 f1; 2g, let cr = cAr+ cBrbe the total funds spent on issue r.

Each voteri2Nhas an ideal political position i = (i1; i2)2[0; 1]2.Preferences of voter i over political parties are represented by the followingutility function:

ui(j; c) =1(c1)[xj1 i1]2 2(c2)[xj2 i2]2: (1)

For each issue r, r(:) is a strictly increasing function of the campaignexpenditures on that issue, with r(0)> 0. We refer to r(:)as the inuencefunctionon issue r. It indicates the weight that voters assign to that issue.

The inuence functions on each of the issues may be dierent.Voter i casts his ballot for party j 6= k when ui(j; c) > ui(k; c): Wesuppose that those voters who are indierent between the two parties ab-stain from voting. Given any prole of campaign strategies c2 C, letVj(c) be the number of votes that party j obtains in the elections, i.e.,Vj(c) = # fi2N :ui(j; c)> ui(k; c)g.

The utility function of voter ican be rewritten as:

ui(j; c) =T(c) [xj1 i1]2 [xj2 i2]2 (2)

where T(c) = 1(c1)2(c2)

is the relative intensity of the preferences of voters over

issue 1 when the prole of campaign strategies is c. The greater T(c), themore relevant is issue 1 compared to issue2 in voters preferences.

Voteriis indierent between the two parties (and then he abstains fromvoting) when his ideal political position satises the following condition:

i2= T(c) [x2A1 x2B1] + [x2A2 x2B2]

2 [xA2 xB2] T(c) [xA1 xB1]

[xA2 xB2] i1: (3)

The line dened by Equation (3) divides the policy space [0; 1]2 into tworegions based on the voters most preferred party. Since each party j canspend at most cj, we have

1(0)

2(cA+cB) 6 T(c) 6 1(cA+cB)

2(0) for all c2 C. We

denote Tmin = 1(0)2(cA+cB) and Tmax =

1(cA+cB)2(0) the minimum and maximum

values ofT(c).Every voterisuch thatui(j; c)> ui(k; c)(withj6=k) for allc2Calways

votes for party j, no matter what the prole of campaign strategies is. Wecall these voters partisan voters of party j.

4

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

6/15

There can be voters such that ui(A; c) > ui(B; c) for some c2 C andui(B; c0) > ui(A; c0) for some c02 C. These voters cast their ballots for oneor the other political party, depending on the campaign strategies. We callthese voters issue voters.5

Given any prole of campaign strategies c2C, partyj wins the electionsifVj(c)> Vk(c)(and therefore, partyk is majority-defeated). For simplicity,we assume that when parties are involved in a tie party Agoverns.

Issue 1

Issue 2

1

1

(xA1-xB1)/2

(xA2-xB2)/2

Tmin

Tmax

T12

1

3

A

B

[ )[ ]

Tmin T1 Tmax

B A

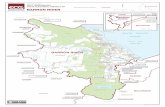

Figure 1. An example of winning partition

Interval[Tmin; Tmax]can be partitioned into dierent subintervals accord-

ing to the party that wins the elections. We call it thewinning partitionof[Tmin; Tmax]. Figure 1 provides an example to illustrate this concept. There

5 Some authors assume that the set of voters inuenced by campaign expenditures is axed fraction of uninformed voters (see, e.g., Baron, 1994, and Grossman and Helpman,1996).

5

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

7/15

are three voters with ideal political positions 1, 2 and 3. The political

positions of the parties are represented by points A andB. Abusing nota-tion we use Tmin (resp. Tmax) to denote the line dened by Expression (3)whenT(c) =Tmin (resp. T(c) =Tmax). The winning partition of[Tmin; Tmax]consists of two subintervals: [Tmin; T1) and [T1; Tmax]. To see this note thatfor allT(c)2[Tmin; T1)the winning party is B (since voter 1 casts his ballotfor party Aand voters 2 and 3 cast their ballots for party B). Similarly, forallT(c)2[T1; Tmax] the winning party is A(ifT(c) =T1 there is a tie).

Political parties aim at winning the elections. Preferences of each partyj6=k are represented by the following utility function:

wj(c) = 1; ifVj(c)> Vk(c)0; ifVj(c)< Vk(c)

(4)

andwA(c) = 1; wB(c) = 0ifVA(c) =VB(c):

We are interested in analyzing under which circumstances a party canensure its victory in the elections. This is the idea behind the concept ofdominant strategies. A campaign strategy of party j, cj2 Cj, is a (weakly)dominant strategy for that party ifwj(c

j ; ck) > wj(c

0j; ck) for all c

0j2 Cj

and all ck2 Ck (j6= k). Note that, in particular, cj2 Cj is a dominantstrategy for partyjthat ensures its victory if and only if

h 1(cj1)

2(cj2+ck);1(cj1+ck)

2(cj2)

iis included in a subinterval of the winning partition where party j wins.6

If a party achieves a majority of the votes for everyT(c)2[Tmin; Tmax]theproblem is trivial. From now on, we assume that the distribution of votersideal political positions is such that the winning partition has at least twosubintervals.7

6 The concepts of dominant strategies and Nash equilibria are closely linked: (cj ; ck)is a

Nash equilibrium of the campaign game where party j wins if and only ifcj is a dominantstrategy that ensures j s victory.

7 In particular, if the winning partition has two subintervals, then there is T1 2[Tmin; Tmax] such that party j wins for all T(c)2 [Tmin; T1] and party k wins for allT(c)2(T1; Tmax]. In this case, if 1(ck)2(cj) T1, cj = (0; cj)is a dominant strategy for partyj that ensures its victory, and if 1(ck)

2(cj) > T1, ck= (ck; 0)is a dominant strategy for party

k that ensures its victory.

6

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

8/15

3 Results

Next, we analyze to what extent three success indicators ensure that a po-litical party cannot be majority-defeated in the elections. These indicatorsare: the advantage on campaign resources, the pre-campaign advantage, andthe advantage on every salient issue.

3.1 The advantage on campaign resources

Having more campaign funds than the opponent does not guarantee theelectoral victory, even if the dierence is extremely large. To see this notethat when a party has a majority of partisan voters, such party wins theelections for all c

2C, even if it has no campaign resources.

3.2 The pre-campaign advantage

The pre-campaign advantage measures the percentage of votes that aparty would obtain if there were no political campaign. We write c = 0 todenote the situation where there is no campaign expenditures. LetT0=

1(0)

2(0)

be the relative intensity of voters preferences over issue 1 in this situation(note thatTmin < T0 < Tmax). The party that achieves a majority in this caseis the pre-campaign winner. The pre-campaign advantage does not guaranteethe electoral victory.

Proposition 1There is no pre-campaign advantage that guarantees that apolitical party wins the elections.

Proof: Suppose that all voters bliss points coincide, and that there is T12[Tmin; Tmax] such that all voters vote for party j when T(c)2[Tmin; T1), andvote for party k when T(c)2(T1; Tmax]. Suppose that T1 < T0. Then partyk would obtain100% of the votes if there where no political campaign (i.e.,party k has the maximum pre-campaign advantage). However, there alwaysexist some inuence functions and amounts of campaign funds such that1(ck)

2(cj) < T1. In this case cj = (0; cj) is a dominant strategy for party j that

ensures its victory.

3.3 The advantage on every single issue

We say that party j has a majority on issue rwhen it wins the hypo-thetical election where individuals only care about that issue. Letnjr be thenumber of voters that, on issue r;strictly prefer party j to partyk. Formally,

7

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

9/15

njr = # i2N : [xjr ir]2 >[xkr ir]2

. Partyj has a majority on issue

r when njr > nkr (j6=k).8

Having a majority on both issues does not guarantee the electoral victory.The electoral victory is guaranteed only if a party holds a suciently largemajority on both issues.

Proposition 2 Suppose that partyj has a majority on both issues. If nj1+nj2

n >

32 , then partyj wins the elections for allc2C(whatever the campaign fundscA; cB 0 and the inuence functions1 and2 are). Otherwise, the elec-toral victory of partyj is not guaranteed.9

Proof. (See Figure 2) Let nAr;Bs 0 be the number of voters that preferparty A on issue r, but prefer party B on issue s, i.e., nAr;Bs = #fi2 N:[xAr ir]2 [xBs is]2g. Let nj = #fi2N: [xjr ir]2 [xkr ir]2 for all r2 f1; 2g, with strict inequality forsome r2 f1; 2gg. Note that, since individuals take into account both issuessimultaneously, thenj voters will always vote for party j (i.e., the n

j voters

are partisan voters of party j). Suppose that, for some party j,nj1+nj2 > 32n:

Since nj1 nj +nj1;k2, nj2 nj +nj2;k1, and nj +nj1;k2+ nj2;k1 n, wehave n2 < n

j and therefore party j will win the elections for every c2C.10

In Figure 2 we provide an example showing that, if nj1+nj2

n 3

2 , then theelectoral victory of party j is not guaranteed even if it has a majority onboth issues. The political positions of the parties are given by points AandB. There are four groups of voters: 50% of the voters have ideal politicalposition1,25% of the voters have ideal political position 2, and25%of thevoters have ideal political position3. Note that

nB1n

= 0:75and nB2n

= 0:75.Suppose that the campaign funds, cA; cB 0, and the inuence functions,1 and2, are such that Tmin andTmax are as depicted in Figure 2. In thiscase, for every c2C, party Aobtains50% of the votes.

Proposition 2 shows that a suciently large advantage on each of theissues guarantees the electoral victory. If the sum of votes that a party

8 We suppose that, if[xAr

ir]

2 = [xBr

ir]

2, then voter i abstains from voting in

the hypothetical one-issue elections.9 The fact that nk1+ nk2 < n2 does not necessarily imply that nj1 + nj2 >

32n, since

some voters could abstain in the hypothetical one-issue elections.

10 This result can be easily generalized to the case ofm2 issues: ifmPr=1

njr > 2m1

2 n,

then party j wins the elections, no matter how much campaign funds the parties have.

8

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

10/15

obtains in the hypothetical one-issue elections is greater than 32n, there is no

way of defeating this party in the elections since it has a majority of partisanvoters. Note that a particular instance for that condition is given when theadvantage of a party on every single-issue is above the qualied majority ofthree-quarters.

Issue 1

Issue 2

(xA1-xB1)/2

(xA2-xB2)/2

A

B

nA1,B2

nA2,B1

n*B

n*A

Tmax

Tmin

1(50%)

3(25%)

2(25%)

Figure 2. Illustration of Proposition 2

When the advantage of a party on single issues does not satisfy the condi-tion stated in Proposition 2, the paradox presented by Ostrogorski reappears.The Ostrogorskis paradox postulates that the party that has a majority onevery single issue may be majority-defeated in the elections by its rival.

If we put together the three success indicators that we are analyzing,we nd a stronger version of the Ostrogorskis paradox: a party may bemajority-defeated in the elections even if it has a majority on every singleissue, is the pre-campaign winner, and has more campaign funds than itsrival.

9

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

11/15

Example 1 (Stronger version of Ostrogorskis paradox). The parties have

the following political positions and campaign funds:

PartyA: xA= (0:3; 0:3) cA= 16PartyB : xB = (0:7; 0:7) cB = 9

There are three voters with ideal political positions1 = (0:1; 0:1), 2 =(0:2; 0:77), and 3 = (0:8; 0:44). The inuence functions are 1(c1) = 1 +p

c1; 2(c2) = 1 + 2p

c2. The relative intensity of voters preferences over

issue1 may vary between Tmin = 1(0)2(cA+cB)

= 111

and Tmax = 1(cA+cB)

2(0) = 6,

depending on the campaign strategiesc2C. Given the preferences of votersover political parties, we have that:

Voter 1 is the only partisan voter of partyA.Voter 2 votes for partyB whenT(c)2[Tmin; 0:9), and votes for partyA

whenT(c)2(0:9; Tmax].Voter 3 votes for partyA whenT(c)2[Tmin; 0:2), and votes for partyB

whenT(c)2(0:2; Tmax].The winning partition of [Tmin; Tmax] represented in Figure 3 has three

subintervals. Note thatT0= 1(0)2(0)

= 1. Therefore partyA is the pre-campaignwinner. Moreover, party A has majority on both issues: on issue 1 it issupported by voters1 and2, while on issue 2 it is supported by voters1 and3.11 Nevertheless, cB = (c

B1; c

B2) = (2; 7) is a dominant strategy for party

Bthat ensures its victory, since

h 1(cB1)2(c

B2+cA);1(cA+c

B1)

2(c

B2)i

=h 1+

p2

1+2p23; 1+

p18

1+2p7i(0:2; 0:9).12

In the previous example, two issue voters are crucial to win the elections.As we have shown, there is a subinterval of the winning partition whereparty B can win the elections. This subinterval can be achieved by slightlyinuencing preferences on both political issues. The key idea is that bymeans of slightly inuencing preferences in this way, party B captures voter2 without losing voter 3: If instead party B spends all its campaign fundson issue 1 or on issue 2, then party A wins. It is important to note that anecessary condition for the above result is that on one of the issues (issue 2),

11 Since 23 + 23 5 = 1(cA)1(0)

:

11

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

13/15

be predicted. We show that neither the pre-campaign advantage nor the

amount of campaign resources can guarantee the electoral victory. Electoralvictory is guaranteed only when a party holds a suciently large advantageon every salient issue, as far as its advantage guarantees that the party has amajority of partisan voters. The strategic emphasis of issues, however, doesnot prevent the misleading conclusion of the Ostrogorskis paradox: we ndthat a party that has an advantage on every salient issue may be majority-defeated in representative democracy (even if it is the pre-campaign winnerand has more campaign resources than its opponent), as long as the sum ofthe one-issue advantages is not too large.

12

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

14/15

REFERENCES

Amors, P. and Puy, M.S. (2007) Dialogue or Issue Divergence in the Po-litical Campaign?, Core Discussion Paper 2007/84.

Bezembinder, T.H. and Van Acker, P. (1985) The Ostrogorski Paradox andits relation to nontransitive choice, Journal of Mathematical Sociology 11,131-158.

Baron, D.P. (1994) Electoral Competition with Informed and UninformedVoters,American Political Science Review88, 33-47.

Budge, I. (1993) Issues, Dimensions, and Agenda Change in Postwar Democ-

racies, in William H. Riker ed., Agenda Formation, The University of Michi-gan Press, 41-80.

Daudt, H. and Rae, D. (1976) The Ostrogorski paradox a peculiarly ofcompound majority decision,European Journal of Political Research4, 391-398.

Grossman, G.M. and Helpman, E. (1996) Electoral Competition and SpecialInterest Politics,Review of Economic Studies63, 265-286.

Kelly, J.S.(1989) The Ostrogorskis Paradox,Social Choice and Welfare6,71-76.

Laond, G. and Lain, J. (2006) Single-switch preferences and the Ostro-gorski paradox,Mathematical Social Sciences52, 49-66.

Laver, M. and Hunt, W.B. (1992) Policy and Party Competition, Routledge.

Ostrogorski, M. (1902)Democracy and the Organization of Political Parties.Paris.

Page, B.I. (1976) The Theory of Political Ambiguity, American PoliticalScience Review70, 742-752.

Petrocik, J.R. (1996) Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980Case Study,American Journal of Political Science40, 825-850.

Riker, W.H. (1993) Rhetorical Interaction in the Ratication Campaign, inWilliam H. Riker ed., Agenda Formation, The University of Michigan Press81-123.

13

-

8/9/2019 Victoria Electoral

15/15

Sigelman, L. and Buell, E. (2004) Avoidance or Engagement? Issue Con-

vergence in Presidential Campaigns,American Journal of Political Science48 (4), 650-661.

Simon, A. (2002)The winning Message: Candidate Behavior, Campaign Dis-course, and Democracy. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

14