Variable Elasticities and Non-Price Rationing in the Import Demand Function of Canada, 1956:1-1973:4

-

Upload

gopal-yadav -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

2

Transcript of Variable Elasticities and Non-Price Rationing in the Import Demand Function of Canada, 1956:1-1973:4

Variable Elasticities and Non-Price Rationing in the Import Demand Function of Canada,1956:1-1973:4Author(s): Gopal YadavSource: The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue canadienne d'Economique, Vol. 10, No. 4(Nov., 1977), pp. 702-712Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Canadian Economics AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/134301 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 15:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Wiley and Canadian Economics Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extendaccess to The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue canadienne d'Economique.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

702 / Gopal Yadav

Variable elasticities and non-price rationing in the import demand function of Canada, 1956:1-1973:4

GOPAL YADAV / International Monetary Fund

I N T R O D U C T I O N

The empirical results presented in this paper were obtained from estimating import demand functions for Canada at a relatively disaggregated level using quarterly data for the period 1956-73 with the following two objectives: first, to assess the importance of non-price rationing, represented by the aggregate capacity utilization rate, for import demand in Canada; and secondly, to test the common assumption that income and price elasticities of import demand are invariant with respect to the size of change in income and price. The specifi- cation of the estimated model is detailed in the following section, and the third section contains a summary of the empirical results. The main conclusions of this paper are summarized in the fourth section, while the sources of data are presented in the last section.

THE MODEL

A simple and often-estimated import demand function relates import volume to the level of real income and the ratio of import to domestic prices of the good in question (see Houthakker and Magee, 1969; Kreinin, 1973; Kwack, 1972; Miller and Fratianni, 1974; Yadav, 1975). Recently it has been hy- pothesized that actual prices are slow to adjust to their equilibrium values and in the short run markets are cleared partly by non-price allocation methods. Changes in imports resulting from the variation in the non-price rationing could not be explained by movements in relative prices and real income. Since data on non-price rationing is not available, we have used the rate of aggregate capacity utilization as a proxy for the non-price rationing. It is postulated that as the rate of capacity utilization increases, the domestic producers of import- ables, instead of raising prices, tend to use non-price rationing, such as increased waiting time, less favourable terms, and reduction or elimination of rebates and discounts (see Artus, 1970 1973; Gregory, 1971; Leamer and Stern, 1970; Robinson, 1968). The resulting effective increase in the domestic price of importables encourages consumers to place their orders abroad. In view of this expected positive correlation between changes in rates of capacity utilization and volume of imports, an import demand function for the ith commodity can be specified as follows:

Mitd = e aoiYitali (PMi/PD i)ta2iG ta3ienit (1)

The author wishes to thank an anonymous referee for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'Economique, X, no. 4 November/novembre 1977. Printed in Canada/Imprime au Canada.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shorter articles and comments / 703

where Mid is the volume of imports of the ith commodity demanded in the long run (the long run is defined as a sufficiently long period for demand to be fully adjusted to changes in prices, income, and the rate of capacity utilization); Yi is the appropriate real income or output variable for determining the demand for the ith commodity; PMi is the fixed weight import unit value index of the ith commodity based on the f.o.b. value of imports denominated in Canadian dollars; PDi is the domestic price of the ith commodity, which is generally re- presented by the fixed weight wholesale or consumer price index; G is the rate of aggregate capacity utilization, which is represented by the ratio of actual to potential real gross national product;' a1i, a2i,, and a3i are the long-run elasticities of import demand for the ith commodity with respect to changes in real income, relative prices, and the rate of capacity utilization, respectively; ql is the error term; and subscript t refers to the time period.

Since we intend to estimate import demand function using quarterly data, it is very likely that the actual volume of imports Mit would adjust to the desired volume Mitd with a time lag. To account for this time lag we have employed the partial adjustment mechanism which, together with equation (1), yields the following expression for logarithm of actual imports (log refers to natural logarithm) :2

logMit -d iaofa + /ia3 1log Yit + flia2ilogRit + Pia3ilogGt

+ (1 - li) log Mit-1 + wi, (2)

where f/i is the coefficient of speed of adjustment, log Rit is log (PMi/PDi)t, wit is a random error term, and coefficients fliali, fia,), fia3i are short-run elasticities of import with respect to changes in real income, relative prices, and the rate of capacity utilization respectively.3

In the past, import functions have generally been estimated on the implicit

1 Estimates of capacity utilization rate in Canada, using different methods, frequencies, and aggregation, are available from Glorieux and Jenkins (1974), Statistics Canada (1974), Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce (1974), and the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (1973). On the grounds of coverage, frequency, length of time period, and methodology, the Statistics Canada's estimates of the GNP gap appeared more suitable for the present study, although for comparison purposes the unemployment rate of males 25 to 54 (which reflects the true labour market condition more accurately than the over-all unemployment rate) is also used. The estimates of potential GNP by Statistics Canada are based on a production function originally estimated by the Economic Council of Canada. Recently, Statistics Canada has also started publishing estimates of capacity utilization rate in manufacturing (1976).

2 For similar specification of the lagged adjustment process, see Turnovsky (1968), Dhrymes (1971, 57-9), Miller and Fratianni (1974), Leamer and Stern (1970, chap. 2), and Yadav (1975).

3 The supply curve of imports is assumed to be infinitely elastic - an assumption which has been used in past studies and which permits use of the ordinary least squares (OLS) techniques ignoring the simultaneous equation bias. Turnovsky's study (1968) of an import demand function of New Zealand finds only small differences in the coefficient estimates when the OLS are used instead of the two-stage least squares technique.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

704 / Gopal Yadav

assumption that changes in income and prices extract a constant and sym- metrical response from volume of imports. The convenience of estimation procedure and the ease of interpretation have often favoured a linear or log- linear import demand function; economic theory provides insufficient guidance in this respect, and hence the issue has remained essentially empirical in nature. In this paper an attempt is made to estimate the differential impacts of large and small changes in income and prices on volume of imports in Canada (see also Goldstein and Khan, 1976; Leamer and Stern, 1970; Prais 1962; Liu, 1954; Orcutt, 1950). For this purpose we specify the following import demand function:

MIV a = y *RitaG3 iegi t, (3)

where

= 7oi + oc7iIA log Yitl

8= yi + y1ifAlogRitl,

A log Yitl I log Yit - log Yt l- 1;

JA log Ritl I log Rt - log Rit- S1;

and gt is the random error term. Equations (3), together with the partial adjustment mechanism, yield the following estimating equation for logarithm of actual imports:

log Mit = fiaoi + gi3coj log Yit + gioaliIA log Yit log Yit

+ /iyoi log Rit + 3iylilA log Ritl log Rit

+ f3ia3ilogGt + (1 - fi)logMt_-1 + vit, (4)

where vit is the random error term possessing the desirable properties of non- autoregression, homoscedasticity, and zero mean.

The coefficients (Bai,, f3i7yo, etc.) measure the short-run or the first-quarter impacts of changes in the respective variables on the import volumes. It is quite possible that the variables designed to test the hypothesis of constant response have significant impact in the short run but not in the long run. The hypothesis of constant response in the long run can be tested by the statistical significance of a and y1. If these coefficients are not significantly different from zero, then q = ali and 8 = a2l, validating the above hypothesis. In order to perform a test of significance on a and yi, the large sample variance of these coefficients would be obtained by Taylor expansion.4 Further, since the

4 If an estimator d is a function of k other estimators such as j , 92... ,7) then the large sample variance of a can be approximated as

Var (a) Z (af/la&)2 Var (A) + 2 Z (Of/l1)(aflak) Cov (Tjh Pk)' k j<k

(j,k= 1,2...,K;j<k). The approximation is obtained by using Taylor expansion for f(gi, 32, ... h) around 13, f2, *.. k, dropping terms of the order of two or higher (see Klein, 1953, 258).

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shorter articles and comments / 705

Durbin-Watson test for serial correlation loses its power somewhat in models involving lagged dependent variables, an h-statistic as suggested by Durbin (1960) would be employed. Whenever h > 1.645, the question was re-es- timated by the search procedure which assumes that the error terms follow a first-order autoregressive scheme (see Yadav, 1975, Table 1 ).

In addition to the variables inentioned in equation (4), a number of dummy variables were also introduced for capturing the effects of some important structural changes on import volumes. Hence, in estimating an import demand function for motor vehicles and parts, a dummy variable AUTO was introduced from the first quarter of 1965 onward to reflect the positive effects of the us- Canada auto agreement. Similarly, dummy variables were introduced from the third quarter of 1971 to the first quarter of 1972 to take into account the positive impact of the us dock strike DOCK,5 in the third and fourth quarters of 1962 to capture the negative effect of the temporary surcharge on food imports SUR2, and between the third quarter of 1962 and the first quarter of 1963 to reflect the negative impact of the temporary surcharge on all other imports SURL.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

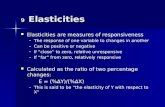

For each category of imports a set of the following three equations was estimated: a/ equation (2), b/ equation (2) with G replaced by the un- employment rate for males 25-54; and c/ equation (4). The results of experi- ments a and b are presented in Table 1 and those of c in Table 3. In order to save space, we have where possible presented only those equations which con- tained statistically significant variables.

The significance of capacity utilization rate The coefficients of capacity utilization are statistically significant and have

the expected signs for all categories of imports except automobiles, other consumer goods, and food. Further investigations, not presented in the paper but available on request from the author, suggest that at least in the case of motor vehicles and parts there was a multicollinearity problem between G and R.6 The capacity utilization variable was dropped from equations for food and other consumer goods as the coefficients of this variable were highly insignif- icant.

In Table 2 the income and price elasticities of demand from these equations are compared with those obtained from the equations that exclude the capacity

5 Since, during the us dock strikes, some of the foreign merchandise destined for the United States went via the Canadian seaports, the value of Canadian imports was artificially and temporarily increased.

6 Automotive and fuel imports are the only two catagories of imports for which the relative price variable remained statistically insignificant in spite of the use of following alternative domestic price indexes: the industrial selling price index of automobiles and parts and the consumer price index of gasoline.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

0

OC)

00 OC)

00 OC) r-A rq

OC) CN rq rq 00

rq rq rq rq rq rq

m rq ON OC) 0 110 110 ON ON ON 00 00 110 kr) 00 00

OC) 0 ON rq

rq o rq 0 0 rq

4-1

rq m rq rq

rq rq rq

OC) rq oo

00 rq 0 rq

01)

rq rq rq OC) 0 tl- OC) OC) kr) tl- rq W) rq 00 oo W)

00 'M- rq rq

oo rq rq 0 110 W') W') 00 00 00 rq rq 00 cn 00 00 m W') blo

rq 1.01 lc

Ln OC) rq oo I'D oo "D L. 00 It 00 I--, 00 \Z -.q 00 oo 4-1 Q oo 4-1 rq rq rq rq rq 00 W) rq

rq 00

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

o t ,< =s ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~o x 11 - - ;,E t

t =3t g t 2.

1 1 1 _ w_ 1 a O~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- v 0 v

>~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ oo: oo > ?E ?i=X =S o~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ o 0 0(S C o:,: ;.. 0

C4 .e 11)

uD m g > o c^ as0 W . 3 3 E Q~~~~~~~~~~~~C 0 to 0 o) 0

o o o N x to O ! c e e~~~~~~ON o N m oN _ 3 4 - H= D=O

4- C r . 0 - r o O =r

m

m t o N i ?o b R N O SH e *: e ? ?

=~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0 0 14 . r n ? m ? o m 4 m N m m ? s; m Q m ?E 0 =~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Z W. O m O m O O1 O N O t ? t .> r s CC: M 5; = 3 3 >>;6 ? E a(A

m . m oo F N ~~~~~~oo CN oo o . ;?. Q ~c,3 O t' O ^, Q O O O m < O X O c, E .~~~~~~~~ ~~~~0 o 5 0 0 ;E1e1

<z) z Q = Q = a W0 E t = 8 0 r ?~~~0 C4 >~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ C) 75 J :~ c) o

3) b

00 ? OtO^ ?? ^C) ,0 X W0 OC) T=?t3 OC t o OC rq m O?? $ ?N ? $ 0 (4 -.................

C 1??U\,N O, O OC,.................oo a o . N 0

w

X > W Q Q s; O; ? Q Sx s ....................................... >

z N o m t t m o ? o W E a n Q = e ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~cI x > _< <, _< *H c, o_ < z; = e g~~~~~~C C) >

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

708 / Gopal Yadav

TABLE 2

Income and price elasticities of demand for imports

Income elasticity Price elasticity Coefficient

First First of Long-run quarter Long-run quarter adjustment

Total imports (1). 1.259 0.546 -1.371 -0.595 0.434 (1.328)b (0.394) (-1.521) (-0.451) (0.297)

Total imports excluding motor vehicles and parts and fuels and lubricants (3) 1.007 0.577 -1.151 -0.659 0.573

(1.052) (0.397) (-1.355) (-0.512) (0.378)

Motor vehicles and parts (6) 2.067 0.306 - - 0.148

Fuels and lubricants (7) 0.831 0.515 - - 0.619 (0.882) (0.362) (-) (-) (0.411)

Producers equipment (9) 1.133 0.624 -1.020 -0.562 0.551 (1.337) (0.329) (- 1.321) (-0.322) (0.246)

Industrial materials (11) 1.049 0.630 -0.812 -0.488 0.601 (1.009) (0.518) (-1.004) (-0.516) (0.514)

Construction materialsc (13) 0.455 0.112 -2.518 -0.620 0.246 (0.746) (0.122) (-3.451) (-0.565) (0.164)

Other consumer goods (15) 1.513 0.273 -3.176 -0.574 0.181

Food (16) 0.791 0.327 -0.613 -0.254 0.413

a Figures in this column refer to the corresponding equation number in Table 1. b Figures in parentheses are the corresponding elasticities and the coefficient of speed of

adjustment obtained from equations which omitted the capacity utilization variable (Table 4).

c Since a good fit could not be obtained for this category of imports, the comparison of elasticities of its demand is not as useful as for the other categories. SOURCE: Tables 1 and 4.

utilization variable (see Table 4).7 In general the speed of adjustment and the short-run income and price elasticities of import demand are appreciably larger when the rate of capacity utilization is included as an argument in the functions. On the other hand the presence of the capacity utilization variable has notice- ably reduced the absolute value of long-run price elasticities for all import categories without exerting similar marked impact on the long-run income elasticities.

Tests for the difjerential response of import volumes to large and small changes In Table 3 it is noted that for a majority of import commodity groups the values 7 On theoretical and empirical grounds (see no. 3), we have preferred GNP gap over

male unemployment rate as the measure of capacity utilization rate used for this comparison and the subsequent tests. We may note that in general the summary statistics (K2, DW, or h) of these equations appear better with GNP gap than the unemployment rate (see Table 1).

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

. oor- - moo 00 Ot ( t 'IC 00 00o 00 Cl Nt r-0 Ooo otF

6 O o ot O O coo

O O O 0 00 0 O O 00

-r) (01 tn en ri O ~ It0 Ioo en(0 'f) r-'

0 ~ C; Cl 00 00> C; 0 CCl;

0 0

It 00 00 em 0 ON cl

Ct Cl

Cl Ct 0

Clq

0 0 C

W0 I ClIt It m C -

m c0 0 00 0 0 0 Cl 0 0 0 c 0 0 0 0 0~~~~~~~~~~~~~~W 0 0c 0f

o ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~ rq tH C sE Soo

C0 oo ? ? tI) 00 00 - ON Q (N a ) Cl Cl (N (O 00 (N o O X O O (D O O O O O O O O

10 0 +,2 - ~ 0

Cl Cl C C l l ClC

- o ON Oo eo t- C O O > so 0 00 00 00tn r oN) 0 oN

ON O ON N 0 N Q Q' 5 5 o an

0o 0? 0 0? 0> 0 0

Cld ~ ~ Cl

Cld t) r- It C O0I

ON 0- ON 0Cl\0n

O m

C)d

._^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~I O _ _ It 'It N k)t) I m

Cld 0~~~~ r- Th A "t10 " (~ O

0 C C 0 l ,

A

- 0Z o M--, \~ 0 ---- Y t e mb moo nae~~~~~~~~o,, CA -ON v)\ m CI o N C t

CO tV O Vf) C rtC "C C; It' C; P~C t C

OC) ,C n0 C

(Av)C 000 o 0 N v)t -o e

0) C o 00_00 0) 0 00 0 0 -0 0

- 0- O It O I - I I 0

U o a oCo o -, o o 0000 0

_ Cv 00 @mo oo v v be- no o m E"oo ozov tn o

ct ,v, ooo to t~~~~~~z N t on ov ov ont on too N

o I~ ,-t 0 I, I _ Ot . 0 N co C

. . -_ -. In Qo oo- > 9 'I0 . O^

= S~'ic ooo-r-oi ooon1 -O- N-o t~0 00 000 HOt N

_ OV)W0 0S 0 OD t '0t0 0m v

U < ;| C3 *, t 4~~~~~~0 - . O l b $X to ~~~~~~~o oF tt6k t S \?> <>l t o U <>l t ?t b t S ; t *e t m X b N btN m t N r:~~~~~~~~-r

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OC) It~~~~~~~~~~~ 4~~~~~ O ~ ~ O~~~~~~~~~~C 0)

<~~0 ~ t Cl F r)

~t C t)

o o o O o o E

C;~~~~~~~~ C)

: o I o~ X i- 0 0 0 0

ON "N N

00~~~~~~~~ C~ ON Cl 0

o O C 0~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0

t; =~~~~v

Q 0 C 0 > o0

o O O~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~o

e o ~ 00 r o 00 o -

.0

C O O CO O m C> O te O G 0 ' =

0~~~~~~~~~~~~~

0)~~~~~~~~~~~~~

00 Cl 00t, Cs f:z, ?? ae ? m in 0 C o m 0m 0 m gO 0

0~~~~~~~~~~~~ c; C;

0~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

O O Cl O*0e 00 0lm 0, 0Cl CO

- 1 ~~~~~~ " - W) : zt o - .

ct~ ~ ~ < C> t o 00 00~f WCICC 0- l) 00 r0 ~ C

0) O O 0 ! c - 0 O 2

o o NO QC0C~) lX Nf ? O m N t o C> Oo

C ;;O Cl) otto;go2G.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Shorter articles and comments /711

of income and price elasticities are independent of the size of changes in income and prices respectively. At 5 per cent level of confidence the larger variations in income appear to have an independent and positive effect on the volume of imports of 'motor vehicles and parts' only. (Notice the absence of such in- dependent impact on 'total imports excluding motor vehicles and parts.' Simi- larly, Orcutt's (1950) proposition that price elasticities of import demand may be larger for large price changes than for small price changes is not sup- ported by any category of imports at 5 per cent level of confidence. Regarding imports of 'other consumer goods,' however, the coefficient 71i is significant but has the wrong sign; the price elasticity of this category of imports becomes smaller in absolute value for large than for small price changes.

C O N C L U S I O N S

This study has shown that non-price rationing, represented by the aggregate capacity utilization rate, is a statistically significant determinant of Canada's demand for imports. As expected, the empirical results demonstrate that the exclusion of this proxy for the non-price allocation mechanism unduly inflates the long-run price elasticities without significantly affecting the long-run income elasticities of import demand. Also, the speed of adjustment is unduly reduced when the capacity utilization variable is excluded from the import demand function.

This study has shown also that at the 5 per cent confidence level the hypo- thesis of constant response of import volumes to changes in real income is valid for a majority of import categories, both in the long and short runs. Regarding relative prices, the above hypothesis is also valid at the 5 per cent confidence level for a majority of import categories, both in the long and short runs. These conclusions are consistent with the results obtained for other countries (Goldstein and Khan, 1976).

DATA SOURCES

Import volumes were derived from the value and price series published in the Bank of Canada Review. All other data were obtained from Statistics Canada. It may be noted that the empirical work for this paper was completed before the National Income Accounts data for 1971-3 were revised. However, the use of revised income data is not likely to alter the equations significantly as the revisions are neither large nor extensive.

REFERENCES

Artus, J.R. (1970) 'The short-term effects of domestic demand pressure on British export performance.' International Monetary Fund Staff Papers 17, 246-76

Artus, J.R. (1973) 'The short-term effects of domestic demand pressure on export delivery delay for machinery.' Journal of International Economics 3, 21-36

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

712 / Gopal Yadav

Department of Industry, Trade, and Commerce (1974) Rate of Capacity Utiliza- tion: Canada, 1st Quarter 1974 (Ottawa)

Dhrymes, P.J. (1971) Distributed Lags: Problems of Estimation and Formulation (San Francisco)

Durbin, J. (1960) 'Testing for serial correlation in least-squares regression when some regressors are lagged dependent variables.' Econometrica 28, 410-21

Glorieux, G. and P. Jenkins (1974) 'Perspectives on capacity utilization in Canada.' Bank of Canada Review Sept., 3-16

Goldstein, M. and M. Khan (1976) 'Large versus small price changes and the demand for imports.' International Monetary Fund Staff Papers 23, 200-25

Gregory, R.G. (1971) 'United States imports and internal pressure of demand: 1948-68.' American Economic Review 61, 28-47

Houthakker, H.S. and P. Magee (1969) 'Income and price elasticities in world trade.' Review of Economics and Statistics 51, 111-25

Klein, L.R. (1953) A Textbook of Econometrics (Evanston, Illinois) Kreinin, M.E. (1973) 'Disaggregated import demand functions - Further Results.'

Southern Economic Jouirnal 40, 19-25 Kwack, S.Y. (1972) 'The determination of us imports and exports: a disaggregated

quarterly model, 1960: in - 1967: iv.' Southern Economic Journal 39, 302-14 Leamer, E.E. and R.M. Stern (1970) Quantitative International Economics

(Boston) Liu, T.C. (1954) 'The elasticity of us import demand: a theoretical and empirical

reappraisal.' IMF Staff Papers 3, 416-41 Miller, J.C. and M. Fratianni (1974) 'The lagged adjustment of us trade to prices

and income.' Journal of Economics and Business 26, 191-8 Orcutt, G.H. (1950) 'Measurement of price elasticities in international trade.'

Review of Economics and Statistics 32, 117-32 Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (1973) The Measure-

ment of Domestic Cyclical Fluctuations, Occasional Studies (Paris) Prais, S.J. (1962) 'Econometric research in international trade: a review.' Kyklos

15, 560-79 Robinson, T.R. (1968) 'Canada's imports and economic stability.' This JOURNAL

1,401-28 Statistics Canada (1974) National Income and Expenditure Accounts, Third

Quarter 1974 (Ottawa) Statistics Canada (1976) Capacity utilization rates in Canadian manufacturing

Third Quarter 1976 (Ottawa) Turnovsky, S.J. (1968) 'International trading relationships for a small country:

the case of New Zealand.' This JOURNAL 1, 772-90 Yadav, G. (1975) 'A quarterly model of the Canadian demand for imports

1956-72.' This JOURNAL 8, 410-22

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 15:09:22 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions