Vanguard 03 - US 1st Infantry Division 1939-45

description

Transcript of Vanguard 03 - US 1st Infantry Division 1939-45

VANGUARD SERI ES

EDITOR: MARTIN WINDROW

US 1st INFANTRY DIVISION

1939-45

Text by PHILIP KATCHER

Colour plates by MIKE CHAPPELL

OSPREY PUBLISH I G LONDON

Published in 1978 by Osprey Publishing Ltd Member company of the George Philip Group 1. - 14 Long Acre, London WC.E 9LP © Copyright 1978 Osprey Publishing Ltd

This book is copyrighted under the Berne Convention. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1956, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by a ny means, electronic, electrical , chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers.

ISBN 085045 .80 5

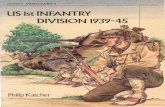

Cover painting by Mike Chappell shows divisional infantry, suppon ed by M4A4 Sherman tank, in the Normandy bocage, June 1944· The tank is a vehicle of the division's a ttached 745th Tank Bn. , finished in Olive Drab and Earth Brown camouflage. Turret and glacis national stars are painted out. The na me 'Angel of Freedom' appears on the hull side, and the bridge plate bears the number '30'. The private on the rear jacket carries the .30 cal. BAR and wears a bell of magazine pouches for this light automatic; the lieu tenant on the front cover carries the .30 cal. M I carbine.

Filmset by BAS Printers Limited, Over Wa llop, Hampshire Printed in Hong Kong

A corporal of the division refuels his Harley Davidson motorcycle during manoeuvres , 1941.

The Beginnings 'The United States Army', goes a saying popular among 1St Infantry Division veterans, 'consists of the 1St Division and ten million replacements.' It is difficult to tell which is being more complimented, the division or the army; for th e record of the division is certainly one of the finest in the army. This has been so since the division was originally created in May 19 I7 as the 1St Division of the American Expeditionary Force. Because it accompanied Force Commanding General John Pershing, the division was originally nicknamed 'Pershing's Own' . In the last days of World War I, however, the division adopted a shoulder patch consisting ofa large red number' I ' on a dark green shield, from which it took its better-known nickname, 'The Big Red One'.

In 1939, facing the real possibility of war, the division was organized as a 'triangular division', made upofthree infantry regiments: the 16th, 18th and 26th. The 16th and 18th had been formed in the spring of 186 I and served in most major battles on the eastern seaboard during th e American Civil War, in the Spanish American War, the Philippine Insurrection and World War I; the 26th had been formed in 190 I and served in the Philippine Insurrection and World War I. Under the triangular division system each regiment became a 'combat team' made up of so me 3,300 infantrymen with supporting artillery, engineer, medical, ordnance, reconnaissance, signal and quartermaster

troops. Besides the infantry, the division had four artillery battalions: the 5th, 7th, 32nd and 33rd Field Artillery. Each battalion was made up of some 550 men. T he 32nd and 33rd were formed from the old 6th Artillery Regiment, which dated back to an artillery company first organized in 1794, The 5th Field Artillery traced itself to Alexander Hamilton's War of American Independence arti llery company. Under the new system the four battalions were organized as I st Division Artillery, or '1st Divarty'.

While the Division was headquartered in Fort Hamilton, New York, in 1939, its units did not get a chance to work together as one organization until the large Louisiana Manoeuvres of 1940. Even at this ea rly stage the division was earmarked for invasion work, and the 18th Infantry Regiment's 3rd Battalion (hereafter written as the '31 18th') was sent for special amphibious manoeuvres training in Culebra, Puerto Rico in 1940. This was followed by amphibious training with the 1st US Marine Corps Division a~ New River, North Carolina, the next year. On 7 December 1941, the day the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor and thrust an onl~ partially ready US Army into war, the division was headquartered at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. Rather than break up its training schedule, the division hurried through more amphibious training in January 1942 on the cold shores of Virginia Beach, Virginia; infantry training followed . In

3

Florida ; some 'Air-Ground Tests and Demonstrations' were carried out at Forl Benning, Georgia, and then the division moved to Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania for final overseas staging. An advance detachment headquarters, along with the 2/16th Infantry, sailed for England from Brooklyn, New York , on 1 July 1942. The rest of the division followed on the Qpen Mary, leaving New York on 2 August 1942 and arriving at Gourock, Scotland on the 8th.

The division went into quarters at a British army cavalry post, Tidworth Barracks, near Salisbury, Wiltshire. The men were a bit surprised by the reality of war- blackouts, petrol rationing and the blitz- after the comparative calm of the States. ''''hen they arrived there were few Am eri ca ns in Great Britain save for a few staff and Arm y Air Corps men , and Limey and Yank found each other equally interesting. Most of the men were pleased by their reception, feeling that the British 'were friend ly and courteous, better hosts than we'd have been if British troops had been in our country'.

Amphibious training was resumed at Tidworth ; and the division took its first casualties when a lone Luftwaffe fighter-bomber strafed one of its platoons during a daytime practice march. Rumours

Artillerymen clean their d isassem bled J05mm howitzer during the 1941 manoeuvres. The g un is still attached to its prime mover, a It-ton lorry; beside it is parked a Dodge Command Car. Note breeches and campaig n ha ts.

4

spread about possible invasion sites: Dakar, Norway, even Brittany. On 3 September 1942 the truth was revealed when Major General Terry de la M. Allen , the divisional commander, was in London on a routine visit to headquarters. From there he excited ly telephoned the. divisional chief of staff, telling him and his top staff officers to report immediately for a conference first thing next morning. The next morning at Torfolk House, London planning headquarters, they learned their real destination - Algeria!

North Africa The American landings in North Africa were to be at three points: Casablanca, Algiers and Oran. The invasion 's .general purpose was to en list French forces on the Allied side, to aid the British in the Libyan Desert, and to open the Mediterranean. In addition, the landings wou ld give the Americans much-needed combat experience, and provide some positive news for ' th e folks back home' .

The 1st Division was assigned Gran as its target, the second largest city in French North Africa at that time. Correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote: ' It reminded me very much of Lisbon. There are modern office buildings and beautiful apartment buildings of six or eight stories. The Renault automobile showroom was full of brand-new cars

when we arrived.' The division sent half the Ist Ranger Battalion to Arzew, a nd the other half to the narrow beaches north of the town to seize the docks, sweep through the upper part of the city and capture and neutralize the seacoast ·defences. The 3/ 18th Infantry was to help the R a ngers, whi le the 1/ 18th was to take St. Cloud and Djebel Khar. The 2/18th was held in reserve. The landing's left flank was to be secured by the 16th In fantry.

Wh en the dim hands of the ship's clocks on the bridge of the SS Reina del Pacifico poin ted to 12.55 on 7 November Ig42, landing craft were launched towards the beaches of the sleeping town . ' It was moonlight', reported Pyle, 'and the beach was deathly quiet. ' Among the first wave went Frenchspeaking soldiers with loudspeakers yelling 'Ne tirez pas ! Ne tirez pas!' to the French defenderswhich, said one participant, 'must have been th e first time in military history that a victorious attacking force cried "Don't shoot! " and it struck the First Division as the funniest thing so far in this cam paign.'

A white flare went up from th e beach fifteen minutes after the first wave was launched- the signal that the landing was ashore unopposed. A red flare soon afterwards indicated that the second wave was safel y ashore, while a green and amber flare at nm indicated that the Rangers had taken the coastal guns .

'French resistance ran the whole scale from eager co-operation to bitter fi ghting to th e d eath', reported Pyle. ' In most sectors the French seemed to fire on ly when fired on. Later we learned that many French troops had on ly three bullets for each rifle, but in other places the 75mm guns did devastating work.' The French positions at Ainel -Turck, Llangibby Castle and Cap Falcon held out all the next day, while other outposts were fairl y quickly overrun. The division had a fair number of problems besides French resistance, however. Accord ing to the d ivision's history, ' by gam practically a ll personnel of the division were ashore and functioning. Heavy equipment was not coming in so well. Very little arti llery had ferri ed ashore. Vehicle ferry ing was even worse. Communications were not functioning satisfactorily. During th e remainder of the day every effort was made to speed up the shore deli very of heavy eq uipment but without too much success.'

The controversial Maj. Gen. Terry de la M. Allen, commander of the 1St Division from 2 August '942 to 6 August '943. (US Army)

The division pushed ahead slowly, held up by French troops dug in at St. Cloud , a town of stone and brick houses. On the morning of the 9th a 15-minute a rtillery barrage hit the town, followed by an assau lt by the 18th In fantry. The French fought dogged ly. Machine guns, expertly sited , cut down the attackers and th e attack slowed to a crawl. The 3/ 16th took a position a t Djebel Kha r, cutting th e St. Cloud garrison's line of retreat, but the French refused to surrender. After considering, and rejecting, a full -scale artill ery barrage, which might have killed many civilians, the division left a battalion to cover the town a nd pushed on. The town itself did not surrender until so ordered by the Oran High Com mand . By midn ight on th e 9th Oran itsel f was su rrounded, with the leading elements of the 3/ 16th in th e outskirts of the city. Confusion, however, had led to delay, and delay was intolerable. The command er of the II Corps, und er which the

5

Master Sergeant Thomas O. Beachamp, the division's oldest member, on a Nonh African beach. Beachamp served in all the division's World War I baules. Note bulldozer in background. (US Army)

division fell, passed on the word that the division was moving too slowly and that the city had to be taken the next day. The whole division prepared to attack at 7.15am on 10 November, with orders from the division's flamboyant commander General Allen that 'Nothing in Hell must delay or stop the I st Division'. Under this kind of pressure the enemy resistance died rapidly. By 8am the division met little more than sniper fire, and by loam a ll fighting was over.

'In spite of incomplete training', wrote overall commander Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower, 'the I st Division, su pported by elements of the I st Armored Division, made progress and on

ovember 9 we knew we would soon be able to report victory in that area . On the loth all fighting had ceased at Oran. Generals Fredendall [II Corps Commander] and Terry de la M. Allen met their initial battle tests in good fashion.'

'At first our troops were rather lost in Gran, officers and men alike', wrote Pyle. 'There weren't the usual entertainments to be had at home and in England. Nothing much was left to drink but wine, and most Americans hadn't learned to drink wine wi th relish. The movies were few and pretty poor.

6

There were no dances. There was a professional "line" but the parents of nice girls in Gran were very fussy and wouldn't let the girls out.' As a result the men probably were not too unhappy when the first of the division's units moved out in November, followed by the 18th Infantry in December. Certainly Allen, a real 'fighting general', was not displeased. Rumour had it that he was so unhappy about the I st being stuck in Oran that he went to headquarters and asked: 'Is this a private war, or can anybody get in?'

The division's troops were part of an effort described by Eisenhower as ' ... the piecemeal process of reinforcing our eastern lines . . . ' There simply was not enough transportation available to make it anything but piecemeal, but the men had to get to the front if Tunis was to be taken. 'Courage, resourcefulness, and endurance, though daily displayed in overwhelming measure, could not completely overcome the combination of enemy, weather, and terrain', Eisenhower wrote. ' In early December the enemy was strong enough in mechanized units to begin local but sharp counter-attacks and we were forced back from our most forward positions in Tunis.'

The division finally reached the lines as one whole unit, holding the area where II Corps and the French XIX Corps met. On the morning of 14 February 1943 Rommel launched an attack against

Il Corps, designed to smash through Kasserine Pass, turn north-west through the Tebessa supply base, reach the coast and cut off Allied units. The 1st US Armored Division was pushed aside, falling hack into the mountains east of Tebessa. XIX Corps flank was exposed, and th e I st Division fell back fifteen miles on 16 February to plug the gap. Here the division fought what Eisenhower called a series of gallant but ineffective actions. What finally stopped the Germans was a combination of their own command problems, a handful of British tanks, and four battalions of the gth US Division's artillery. Fearing a cou nter-attack on the Mareth Line from the British 8th Army, Rommel feli back to his original positions. One casualty of Rommel's attack at Kasserine was General Fredendall. His divisional commanders had lost faith in him, and on 7 March, with a blare of sirens and a plume of dust from a cavalcade of armoured scout cars and half-tracks, Major General George Patton arrived to assume command of II Corps.

Kasserine had been a German victory, although not the total success Rommel wanted and needed; it had been a victory which cost the Germans heavily in terms of men and material. Thereafter they were capable of on ly small , localized counterattacks, and in March the Allies were ready to rcturn to the offensive. On the evening of 16 March the I st Combat Engineers moved out towards Gafsa, digging up over 2,000 Teller mines from roads leading towards that town. On the morning of the 17th the rest of the division was ready to take the town from its Italian garrison - which might have been more difficult had the Italians not abandoned the town some time before! The division then moved east through the El Guettar corridor towards Gabes. Patrols found the Italian 'Cenlauro' Armoured Division across that road, east of El Guettar, with more enemy troops occupying the Maknassy Gap and threatening Gafsa. On the evening of20 March a flanking unit made up of the I st Rangers, Co. D of the I st Engineers, and some 'divarty' support was sent to capture Djebel El Ank, while the 18th Infantry moved parallel to the highway to the south, and the 26th to the north.

An officer with the flanking party described the night-time march as I •• ' marching on a hard surface so littered with small and medium pebbles and rocks the size of two or three fists held together

that there was nowhere a space between them to set a foot firmly on the solid ground. Moreover, the ground beneath these rocks was not level but rising. As it rose, it seemed to weave and tilt from side to side, so that sometimes we walked up a slope and sometimes a long one side of a slope and sometimes along the other. The only thing that was constant at the beginning of the march was at the end of any given ten steps we were several feet higher than we have been at the beginning'. When dawn broke the men were in position. 'All along \,he side of the plateau towards the enemy, there 'were big rocks quite close together like a roughly made stone fence. Behind each crouched a doughboy. It was the firing line, and as we walked across the plateau first one man and then another would raise his rifle and steady it on the rock, or lying down place his rifle alongside a boulder and fire a shot.' A halfhour later the men charged the Italian positions. 'You cou ld not pick the sounds apart. It was like a continuous, rippling explosion. It was the fire of to~my guns and rifles and the explosions of the grenades the men were throwing ahead of them.' And then, 'The only movement beyond the road was the waving of the little white symbol of surrender. And then running, scrambling, trying to keep its footing and its balance with its little hands in the air, a tiny gray figure coming down towards where the doughboys waited. And then another and another.' The road fork east of El Guettar had been secured.

Elsewhere along the road enemy resistance stiffened, reinforced by a battle-group of the German loth Panzer Division. An enemy counterattack on 23 March penetrated Allied forward positions, but faltered by gam. Another was scheduled for 4pm, but the Allies were waiting. Patton, on a vantage point with the I st Division, watched the thin enemy skirmish lines approach, only to be swept away by a mass artillery and small arms fire concentration. 'Theire murdering good infantry' he said , shaking his head. 'What a helluva way to waste good infantry troops.' The Germans left behind them the burned-out hulks of thirty-two of their precious tanks, and the Americans resumed their forward pace, slowly and against steady enemy opposition. The ground they stumbled over was as tough an enemy as the Germans, and that was say ing something: divisional intelligence

7

Banery of 155mm howitzers in act ion against Cerman posi tions south ofEI Cueuar, Tunisia , in typical North African terrain. (US Army)

spotted units of not on ly the loth Panzers and 'Centauro', but also Fallschirmjiiger of the Ramcke Brigade, the Panzer Grenadier Regiment 'Afrika', and a battle-group of th e 21st Panzers. With them were the deadly '88s', an enemy artillery piece which was admired and ha ted in equal measure.

With the Battle of El Guettar won, the high command made its plans for Tunis's final capture. These called for transferring the whole I I Corps some 150 miles, through British lines of communication, to a new spot on the north Rank of the British 1st Army. Once in position the Corps, along with the British 1St and 8th Armies, would begin a series of co-ordinated a ttacks, with the bulk of the fighting and the city's final capture fa lling on British shoulders. 'Neither the Americans nor the French', says the division's history, 'were considered capable of major accom plishmen ts, due to the mountainous terrain of their respective sectors.' The move took more than 30,000 vehicles and 110,000 men to th eir new position. It called for the most difficult and expert kind ofstalfwork, both in moving the Americans and in keeping the British in supply. I t was a success; the enemy was taken completely by surprise.

On the night of 22- 23 April the 1St Division launched its first attack in the new sector. Facing it were Germans of the 334th Infantry Division, the Luftwaffe's Barenthin Paratroop R egiment, the 47th (Autonomous) In fantry Regiment, an anti: tank battalion from the division's old friend the loth Panzers, and various smaller units. The

8

ground was treeless and characterized by numerous small hills.

'The Germans', wrote correspondent Pyle, then with the 1St Division, ' lay on the back slope of every ridge, deeply dug into foxholes. In front of them the fields and pastures were hideous with thousands of hidden mines. The forward slopes were left open, untenanted, and if the Americans had tried to scale those slopes they would have been murdered wholesale in an inferno of machine-gun crossfire, plus mortars and grenades. Consequently, we didn' t do it that way. We fell back to the old warfare of first pulverizing the enemy with a rtillery, then sweeping around the ends of the hill with infantry and taking them from the sides and rear.' It was tough fighting , and it wasslow fighting ; but the 1St handled it wel l.

General Omar Bradley, then commanding II Corps, noticed that 'The initiative of the 1St Division was apparent even in Allen 's mess, where his rough table boasted rare roast beef while the oth er division COs made do with conventional tinned rations. The meat, Terry explained, was 'casualty' beef, from cattle accidently killed by enemy fire . Despite the warnings from vets about sick cattle, those casualties happened with suspicious freq uency. Terry sa t with his black hair dishevelled , a squinty grin on his face. He wore the same green shirt and trousers he had worn through the Gafsa campaign. His orderly had sewn creases into his pants but they had long since bagged out. The aluminium stars he wore had been taken from an Italian pri vate.

'Although Terry had become a hero to his troops, he was known as a maverick among the senior

commanders. Always fighting to keep his 1St from "being dumped on by the high comma nd", Terry was fiercely antagonistic to any echelon above that of division. As a result he was inclined to be stubborn and independent. Skilful, adept, and aggressive, he frequently ignored orders and fought in his own way. I found it difficult to persuade Terry to put his pressure where I thought it should go. He would ha lf-way agree on a plan, but somehow once the battle started this agreement seemed to be forgotten.'

By 13 May the division had made a ten-mile advance, winning full control of the hills north of Tine Valley. On that day the enemy surrendered in Tunisia, leaving the 1St worn out and exhausted. Fighting for seventeen days in northern Tunisia had cost it 103 men killed, 1,245 wounded and 682 missing. Each rifle company was now little more than a reinforced platoon. Moreover, there was a feeling among the men of the Big Red One that their hard work and losses had not been fully appreciated. 'Apparently there were some intimations in print back home that the 15t Division did not fight well in its earlier battles', wrote Pyle . 'The men of that division were wrathful and bitter about that. They went through four big battles in North Africa, made a good name for themselves in everyone, and paid dearly for their victories. If such a criticism was printed, it was somebody's unfortunate mistake.'

The division made its ire known quickly. While Allied troops were holding a victory parade through Tunis, the division returned to a rest camp near Oran, leaving behind it what General Bradley called ' . .. a trail oflooted wineshops and outraged mayors'. Serious trouble began when the troops reached Oran. According to General Bradley: 'The trouble began when SOS (Services of Supply) troops, long stationed in Oran, closed their clubs and installations to our combat troops from the front. Irritated by this exclusion the 1st Division swarmed into the town to "l iberate" it a second time.

'Because of the brief layover between the Tunisian and Sicilian campaigns, we had previously turned down a suggestion that II Corps troops be issued the summer khaki worn by service units. Not only are khakis impractical for field wearl but the change-over would have un-

necessarily burdened supply. Furthermore, the change back again into woollens would have given away the timing of our invasion. Thus the woollen uniform in Oran became the unmistakable badge of troops from the Tunisian front. As long as bands of the 1st Division hunted khaki-clad service troops in Oran, those sweaty woollens were the only assurance of safe-conduct in the cityls streets. When the rioting had gotten out of hand, Theater sternly directed me to order Allen to get his troops promptly out of town. While the episode resulted partly from our failure to prepare a rest area for troops back from the front, it a lso indicated a serious breakdown in discipline within the division. l

The division, having vented its collective spleen, went back to training. An amphibious training school was set up for yet another landing- with mixed results at first. One practice landing was watched critically by the US Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, and Generals Eisenhower, Patton and Bradley. Thedivision landed haifa mile from its target, blinded, they said, by British spotlights. These, they hopefully noted, would be knocked out in a real landing.

16th Infantry command conference at Kasserine Pass. Note mixture of 'tanker's jackets', wool shirts, M '94' field jackets, and headgear. (US Army)

9

1St Divis ion infantry practise amphibious landing techniques at POrt Aux Paules, Algeria , shortly before the invasion of Sicily. (US Army)

Sicily As the Tunisian cam paign was obviously drawing to a close, planning was goi ng ahead for the next invasion target : Sicily. 'At Casablanca the Sicil y operation was decided upon for two reasons,' wrote Eisenhower, 'th e fi rst of which was its great im media te advantage in opening up the Mediterranean sea routes. The second was that because of the relat ively sma ll size of the island its occupati on a fter the capture would not absorb unforeseen amounts of allied strength in the event tha t the enemy should undertake any large -scale counteraction. '

T he I st Division was to take part in this invasion as th e left flank of the II Corps, still und er General Brad ley, with the 45 th Infantry Division on the right. The 1st, reinforced with two R anger Batta lions, would land a t Gela. Following a la rge-sca le practice landing on 24 June 1943, th e division embarked in a fl eet of land ing craft and was ofT on its next campaign . On 10 July, at 2.34am, the fi rs t R angers set foot on th e soil of Sicil y, followed within ten minutes by assault waves of th e 16th and

10

26th Infantry. Defending were elements of the Italian (Assieaa,' (Aosla' and (Livorno' Divisions, Autonomous Coastal Defence R egiments a nd Bersaglieri. Despite their impressive titl es, th eir defence was a t best spotty and slight. The Division 's advance command post was ashore and in operation before noon.

The unimpressive initial defence soon gave way to a major counter-attack by the crack German (Hermann Goring' Panzer Division. * Hearing far more gunfire than was expected , Genera l Bradley made his way to the division's command post. 'A dog-tired T erry Allen wa ited for me in a makeshift CP near the beach. His eyes were red from loss of sleep and his ha ir was dishevelled . His division was still under serious attack.' Over twenty German Mark IV tanks were driving towards Gela and another forty had cut across th e division's front, both forces coming togeth er to break through and push almost to the water's edge. Artill ery and antitank guns were still being dragged ashore. Not even regimental anti-tank guns were in action yet. What a rtillery was ashore was going into ba ttery firing positions right on the beach, firing practicall y point-blank into th e on-coming Germans. ava l gunfire was called in.

·Su Vanguard 4. Fallschirmpanzerdivision 'Hermann Goring' .

The division was not beaten yet. The 16th's regimental commander, seeing his regiment overrun everywhere, ordered 'Everybody stays put just where he is! ... Under no circumstances wi ll anyone be pulled back. Take cover from tanks! ... Don't let anything else get through. The Cannon Company is on the way ... Everyone to hold present positions.' This is exactly what happened. The men dug themselves into foxholes and let the tanks rumble by. Then they popped up to mow down the German grenadiers following the tanks. This task was relatively easy since the Germans did not have enough grenad iers avai lable for the job. Tanks were hurled in, trying to catch the Americans before they could get enough artillery ashore; but the attack was launched before there was enough German infantry on hand, and what few were available were quickly checked. At the same lime the American arti ll erymen's efforts and accurate naval gunfire lOre the tanks apart. The Germans attacked with over sixty tanks of which less than half finally retreated.

The threat had been a real one, however, and the action close. The Germans were stopped only some 2,000 yards from the beach. General Bradley

--,--,

wondered' ... whether any other S division could have repelled that charge in time 10 save the beach from tank penetration. Only the perverse Big Red One with its no less perverse commander was both hard and experienced enough 10 take that assault in stride. A greener division might easily have panicked and seriously embarrassed the landing.' A later, smaller attack was also driven ofT, finally convincing the enemy that ships could outshoot tanks.

Although the enemy reinforced their Panzer units with infantry during the night, the 1st, supported by elements of the 2nd Armored Division and the 82nd Airborne Division, was able 10 move forward on schedule. The paratroops were supposed to be dropped on the Farello landing field, but 'friendly' anti -aircraft fire, accounting for 23 ou t of 144 troop-carrier aircraft, had pretty well broken up the airborne assault. Some paratroops landed as far away as thirty-five miles from their

Landing an M7A I I05mm selr-propel led howitzer 'Priest' on a Sicilian beach ; note typical stowage details. US Signal Corps I

II

A '240mm howitzer towed by the turretless converted chassis of a Lee tank on an I tali an road this was the largest mobile gun employed on this front. Note chalked 5th Army tactical signs on trackguard. (US Signal Corps)

planned drop zones; but their isolated units went into action independently, often under local command of 1st Division elements. Jack Belden, with the I st, ran across two 82nd men who had become separated from their company. 'After many varied adventures, one of which included hiding for several hours in a tree') Belden wrote, 'they escaped back to our lines, bringing forty prisoners with them. One of the lost men, a sergeant, was so proud of his prisoners that he had made the lieutenant to whom he delivered them on the beach sign a receipt for them. '

By the morning of 12 July, despite counterattacks, it was clear to all that the division's beachhead was secure. On the 13th the 18th Infantry quickly took Mt. Ursina, north of the Ponte-Olivo airport, while the 26th Infantry fought for Gibilscemi. In this fighting the 16th lost a great many men , including Lieutenant Colonel Joseph B. Crawford, 2/ 16th commander. Company G, 2/ 16th, took Niscemi before nightfall. The next

12

morning the 26th continued its forward move, taking Ml. Figare, Mt. Canolotti and Ml. Gibil scemi, and opening up the Ponte-Olivo airport for Allied use. As in Africa, fighting over the hilly Sicilian landscape was slow and tough. The enemy still had an active air force which harassed the division both on the beach and on the fighting line. Enemy artillery was heavy and accurate. Still the Allied advance continued: the 2/26th entered Mazarino on 14J uly; the 1/ 18th took La Serra after a sharp fight on the same day and the Rangers captured Butera, an 'impregnable Italian stronghold' , by ISJuly.

Considering the tough enemy resistance and their well dug-in positions, II Corps 'beefed up' the division with a medium howitzer battalion, the 70th Light Tank Battalion and a battery of Issmm guns from the 36th Field Arti llery. Thus reinforced, the 26th I nfantry was sent to sieze Barrafranca.] ust as the attack was ready to begin the unit was hit by concentrated nebelwerfer fire , temporarily disorganizing the 26th. The American ISSS soon found the range and drove the Germans ofT, but a tank battle between the 70th and some German Mark IVs got under way while the US artillery was

dealing with the lIebelwerfers. The 70th was forced back. By noon reinforcements from the 2nd Armored Division arrived, and the Germans were pushed back in their turn. By nightfall the 26th had secu red Barrafranca.

On 17 July the 16th In fantry had pushed on, taking the high ground north-east of Pietraperzia, capturing an Ita lian infantry company and an assortment of Germans. Their reconnaissance discovered that the enemy was preparing a defensive line south of Enna and Caltaniscua, manned by the 15th Panzer Division, the 71 st Nebelwerfer Battalion and elements of the 382nd Infantry Regiment. Enna was both Sicily's capital and headquarters for the island's defenders. Under fire the 1st Engineers built a bridge across the stream running by the town and the 70th Tanks moved across it. Opposition was very heavy, knocking out three medium and five light tanks. II Corps ordered the 1st to take Enna despite any opposition. The 16th In fantry then took the high ground south-east of the town while the 70th surged down the main road going into it. Suddenly the enemy seemed to fall apart, and by noon both regiments were in the town, the opposition dwind":

A squad of the division's 16th Infantry Regl. 'mops up' in Troina, Sicily, August '943. (US Army)

ling to a few badly directed arti llery shells. 'Not bad', said onc high-ranking American

officer on hearing of Enna's fall. 'Not bad at all. It took the Saracens twenty years in their seige of Enna. Our boys did it in five hours.'

The general strategy called for the British to move up the island's east side, taking Messina, while the Americans cleared the west. The enemy was expected to offer the Bri tish the most resistance, since Messina's loss would cut them ofT from the mainland. By 20 July it was clear that the British alone could not take Messina, so both armies were sent after that prize. By 23J uly the US 45th Division reached the sea and cut the island in half. The Americans then turned east, towards the German positions which were blocking the British advance at Catania. The division fought its way slowly towards Nicosia, spending precious time and lives on objectives with unromantic names like Hills 1027 and 825; and by 10.15am on 26 July the division's 91 st Reconnaissance Squadron was just south of Nicosia. The next day the division cut the

13

Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner, who joined the 16th Infantry as a private in 1910, commanded 'Big Red One' from 7 August 1943 to 10 December 1944. (US Army)

road leading east from Nicosia. The enemy fought fiercely, on the ground and in the air, and the city, largely defended by the' Aosla' Division, did not finally fall until 28 July.

The enemy, covered by the I st Battalion, Panzer Grenadier Regiment I I I, fell back to previously prepared positions around Troina. The division followed, and found that the enemy was not going to give up Troina easi ly. While the 26th Infantry cut the road running from Troina east to Ceasare and the 16th took the heights east of the town, the 39th Infantry moved directly towards Troina. The division found itself in its toughest fight yet. An attack on the town launched on I August was met by a counter-attack which forced the Big Red One back to its original lin es. 'Troina's going to be tougher than we thought', telephoned General Allen to General Bradley. 'The Kraut's touchy as hell here.'

14

Not just one, but twenty-four German attacks left the division stalled in its tracks. Allied air support was sent in, along with ground reinforcements from the 9th Infantry Division. A total of eighteen artillery battalions hammered the enemy positions. The division inched forward, spending lives for every foot of ground. Enemy prisoners proved to be dazed by continuous bombing and shelling, but the Germans still fought stubbornly for every position. The 18th In fantry managed to take the high ground overlooking the town and eventually, after fighting for almost a week, the Germans had had enough. They began pulling out. By 8.40am on 6 August the commander of 3/16th was able to report that he had 'a patrol of seven men in town. Snipers in town. Enemy I I kms the other side ofTroina, north-east. The 2nd Battalion' patrol in the south of the town.' Troina had fallen.

After continuous combat from the initial landing up to the capture ofTroina, and losing 267 killed, 1184 wounded and 337 missing, the 1st Division needed a rest. Held in Troina, the division was assigned to [I Corps reserve, while attached units were reassigned to other divisions. The division was to lose two more men while in reserve, however.

'Early in the Sicilian campaign', Bradley wrote, ' I had mad e up my mind to relieve Terry Allen at its conclusion. This relief was not to be a reprimand for ineptness or ineffective command. For in Sicily as in Tunisia the 1st Division had set the pace for the ground campaign. Vet I was convinced ... that Terry's reliefhad becom~ essen tial to the long-term welfare of the division.

'Under Allen the 1st Division had become increasingly temperamental, disdainful of both regulations and senior commands. It thought itself exempted from the need for discipline by vi rtue of its months on the line. And it believed itself to be the only division carrying its fair share of the war.

'To save Allen both from himself and from his brilliant record and to save the division from the heady effects of too much success, [ decided to separate them. Only in this way could I hope to preserve the extraordinary valu e of that division's experience in the Mediterranean war, an experience that would be of incalculable value in the Normandy attack.'

At the same time General Bradley decided that the division's second in command, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, would also have to go. The division's new commander would find it hard to win the confidence of the Big Red One wh ile the well -loved and independent-minded Roosevelt still served in it; besides, Allen would be very hurt if he went and Roosevelt stayed. Both men were surprised and hurt by the move, but they quickly overcame their feelings. Allen trained and took the 104th Infantry Division through Europe to the Elbe. Roosevelt earned the. Medal of Honour on the beaches of Normandy. Sad ly, he died of a heart attack in France before he cou ld receive his own division to command.

Major General Clarence R. Huebner was named to command the 1st Division. General Huebner had been serving behind a Pentagon desk, but he had the advantage of having worn the Big Red One patch since his enlistment as a 16th Infantry private in 1910, while holding every rank from private to colonel. His first move was to gel the division into a bivouac camp near Troina where he put them to work reorganizing and training. Part of this training included what is lovingly known as 'bull' to British soldiers and 'chicken shit' to G Is. The division's battle-hardened 'dog-faces' found themselves doing close-order drill again. The men were not happy, but General Huebner knew that the division had been earmarked for the final invasion of Hitler's 'Fortress Europe'. They had to be remoulded into one of the Army's typical divisions for what was to be their finest momenl.

IBloody Omaha' Dayson the drill field passed quickly enough, and by 8 ovember '943 the division, after another sea voyage, found themselves in Liverpool. There would be time for more training before that day in June, picked for a combination of moonlight and low tides, when the d ivision would be ofT for its last landing. The coast on which the division was to land was not one the Germans planned to give up easily. Field Marshal Rommel had been placed in command of French coastal defences, and achieved impressive results with indifferent resources. Along the beach, just beneath the waves at high tide, ran a

string afiran triangles, wooden stakes and concrete cones, all topped with mines. These were strung together by miles of barbed wire. Beyond this line of defences were mined beaches- mines of every type and size, ranging from anti-personnel to anti-tank . Over five million mines were strewn up and down the French coast. Yet further back was a wall of concrete, studded with pillboxes and covered by Rame-throwers, artillery and rocket launchers. Behind this was a belt of country with open fields staked and mined against parachute drops.

The 1St Division, now numbering 34,142 men and 3,306 vehicles including reinforcements from attached units, was assigned to the V Corps. This corps had been given the job of securing a beachhead in the area between Port-en-Bessin and the Vire River. From here the corps would be aligned with the British 2nd Army and would push south toward Caumont and St. Le.. The landing would be made in four waves, and the I sl received the honour of being assigned to the first wave . The division would land on a beach called 'Omaha', which was divided into five sectors named, from left to right, 'Dog Red', 'Easy Green' , 'Easy Red', 'Fox Green', and 'Fox Red'.

Sgt.:"J". T. Kimbell , Ballery B, 5th Field Artillery, examines an abandoned German 37mm AT gun on the road near Muringen , Belgium. (US Army)

'5

While heavy enemy resistance was expected, great hopes were pinned on a new secret weapon, the DD tank. These tanks were simply Shermans fitted with canvas 'water wings' and an auxil iary propeller. With their machinery sealed watertight, the tanks could 'swim ' ashore and go into action immediately. The advantage these tanks would give was offset by the fact that the planners thought that 'static' training divisions would be manning the defences. This was not the case at Omaha. The combat-ready German 352nd Division just happened to be under training at repelling landings in that region. Allied firepower would be beefed up by the US Navy's covering force, which included four battleships, four cruisers and twenty-six destroyers. Some 8,000 rockets were to be fired at the beach for ten minutes just before the first wave went in.

On 23 March the division was alerted to be ready to move into marshalling areas at short notice. On 7 May the division received that alert, and by I I May it was ready to go. The day was picked- 5 June. Unfortunately the weather failed to co-operate with the conditions needed for a successful invasion. The men were loaded into landing craft, and there they waited whi le a constant rain fell from thick grey ski es. At least one landing craft was washed by waves so high th at they poured in over one end of the loaded craft and right on out over the other. The rations were cold , a nd often stayed down for too short a time for that to make any real difference. The chances of invasion looked so dim that Rommel left France to be home in time for his wife's birthday.

evertheless, the Allies knew that any substantial delay would be disastrous. It would be another month before perfect tide and light conditions would recur: an ebb tide at first light, exposing the carefully placed German anti-landing devices. Keeping the preparations secret until then , when so many soldiers now knew exactly what was due to happen, would be impossi ble; so the decision was made- one day's postponement, and invasion on the 6th.

'All around us the LCVPs churned through the waves with their cargoes of seasick, miserable troops, disgorged from the ships spread as far as one could see in the misty gray dawn of 6 June. Amphibious 'ducks' and tanks wallowed through the waves like strange monsters of the deep', wrote

Don Whitehead, who landed on Easy Red. The invasion was under way. Throughout the night, the largest armada ever gathered chugged through the choppy seas towards German-held France. The first wave of infantrymen jumped into the water some distance from the beach and headed ashore just as dawn broke. From that first instant there were problems. The water-proofed DD tanks, in which so much hope had been placed , were

. floundering and sinking, usually taking their crews with them. Of thirty-three DD tanks sent towards Omaha, twenty-seven went down without firing a shot.

Photographer Robert Capa was with the first wave landing on Easy Red: 'The boatswain lowered the steel-covered barge front, and there, between the grotesque designs of steel obstacles sticking out of the water, was the thin line of land covered with smoke- our Europe, the ' Easy Red ' beach.

'My bea utiful France looked sordid and uninviting, and a German machine gun, spitling bullets around the barge, fully spoiled my return. The men from my barge waded in the water. Waist-deep, with rifles ready to shoot, with the invasion obstacles and the smoki ng beach III the background- this was good enough for the

Pre. Clilford Kangas, 16 lh Infalllry, radios from his uninviting observat ion post near Moderseheid , Belgium, January 1945. Notc woo ll en 'beanie' worn under helmct , and snowcamouflage cover worn over it. (US Army)

- I

photographer. I paused for a moment on the gangplank to take my first real picture of an invasion. The boatswain, who was in an understandable hurry to get the hell out of there, mistook my picture-taking attitude for explicable hesitation, and helped me make up my mind with a well-aimed kick in the rear. The water was cold, and the beach still more than a hundred yards away . The bullets tore holes in the water around me, and I made for the nearest steel obstacle. A soldier got there at the same time, and for a few minutes we shared its cover. He took the waterproofing off his rifle and began to shoot without much aiming at the smoke-hidden beach. The sound of his rifle gave him enough courage to move forward and he left the obstacle to me . It was a foot larger now, and I felt safe enough to take pictures of the other guys hiding just like I was.'

The Germans defending the beach assaulted by the 1st Division were from the 726th Infantry Regiment, 716th Infantry Division. Behind them was the previously unreported 352nd Infantry Division. The 352nd immediately took up positions in support of the 726th. The firepower they put down was tremendous. One American private, jumping into chest-deep water, saw the men before him cut down as they left the landing ramp. Once in the water himself, he watched with a sense of curiosity as German machine-gun fire tore through his clothing, knapsack and canteen. He later said he ' felt like a pigeon at a turkey shoot '. Wh en he reached the beach he found he had been wounded twice, in the back and right leg.

Others, too many others, did not get away with such light wounds. Whole companies were disappearing. Others were landing in the wrong spots and going to ground, hiding anywhere to ge t out of that deadly fire. By 7am the second wave was landing on Omaha, only to find their way blocked by wrecked equipment, corpses, and living men frozen behind whatever cover they could find. The engineers responsible for demolishing German anti-invasion devices were also being picked ofT, while barges with their equipment were being sunk. The engineers did what they could - not nearly as much as they were supposed to be able to do- and joined the infantry behind the sea wall on the beach. Casualties in the Special Engineer Task Force, the group which was to demolish the devices,

Maj. Gen. Clift Andrus had been 'Divany' commander before laking over [he division on II December 1944; he commanded it until, July '945. (US Army)

ran to 4 1 per cent, mostly suffered within the first half hour of landing. With the men tired and seasick after a rough night spent in the boats and a rocky ride across the Channel, and now und er very heavy fire , the invasion, at least on Omaha Beach, seemed to be stalled. Correspondent Whitehead ' lay on the beach wanting to burrow into the gravel. And I thought: "This time we have failed! God, we have failed! Nothing has moved from this beach and soon, over that bluff, will come the Germans. They'll come swarming down on us." ,

From the reports General Brad ley was receiving, he was getting the same impression. Already he was planning to divert Omaha reinforcements to Utah and the British beaches. Several aides were sent in a small boat to look over the beach front scene. 'They returned an hour later, soaked by the seas', wrote Bradley, 'with a discouraging report of cond itions on the beach. The 1st Division lay pinned behind the sea wall wh il e the enemy swept the beaches with small-arms fire. Artillery chased the landing

17

craft where they milled offshore. Much of th e difficulty had been caused by the underwater obstructions. Not only had the demolition teams suffered paralyzing casualties, but much of th eir equipment had been swept away. Only six paths had been blown in that barricade before the rising tide halted their operations.

'Had a less experienced division than the 1st Infantry stumbled into th is crack resistance, it might easily have been thrown back into the Channel. Unjust though it was, my choice of the 1st to spearhead the invasion probably saved us Omaha Beach and a catastrophe on the landing.'

For already, men on Omaha were getting their second wind and moving out of there- right towards the Germans. Brigadier General Willard G. Wyman , assistant divisional commander, studied the situation a few minutes. 'We've got to get

Wounded riflemen of the 18th InfalHry being brought in on a tracked 'Weasel' during the fighting at Hepscheid, Belgium, in January '945. Note white camou fl age applied over olive drab basic paint scheme, and interesting 'reversed' national markings. (US Army)

these men off the beach', he said , 'this is murder!'. H e began moving from unit to unit, getting them into their correct positions and inspiring them. His aide, Lieutenant Robert Riekse, was also on the move, passing on the general's instructions until downed with a severe hip wound. On another part of the beach the 16th Infantry's commander, Colonel George A. Taylor, was also coining a ph~ase. 'Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die. Now let's get the hell out of here.'

The lower ranks, although employing less memorable language, were also up and on their ways. Sergeant Raymond Strojny, who had become, in his words, Just a little mad', rallied his men, led them through a minefield and knocked out a pillbox with a bazooka. Sergeant Philip Streczyk virtually shoved and kicked men off the beach and through the minefields, where he cut his way through barbed wire. A captain saw him return and watched in horror as the sergeant stepped on a Teller mine. It did notgo off; ' it didn ' t

go off when [ stepped on it going up, either, Captain', remarked the sergeant coolly.

By 1.30pm Bradley received the word: 'Troops formerl y pinned down on beaches Easy Red , Easy Green, Fox Red advancing up heights behind beaches.' The division was beginning to drive towards the road which ran parallel to the beach some 1,500 to 2,000 yards beyond it. The men moved forward in small units, mostly in groups no larger than a company. Each one had the uncomfortable feeling of being in the on ly advancing unit , as contacts between them were irregular at best, and hedgerows and sma ll enemy groups cut observation to left and right. The Germans were beginning to pull back from the beaches, towards a defensive line along the road . As a result no unified command or plan of attack was really in operation. Under Lieutenant Colonel Herbert C. Hicks] nr. of the 2/ 1 6th, tha t ba tta lion 's G Company and part of E Company reached the road about noon, pushing several hundred yards further inland by evening. By 1 pm Companies Band C reached the road. By

evening the 3/ 16th was blocking the highway at Le Grand -Ha meau. The 26th Infantry and th e division's command post landed that evening.

'D-Day' was over. Some 3,000 men of th e 1St

Division were killed, wounded or missing. The 16th Infantry alone lost a bout 1,000 men. Staff Sergeant Alfred Eigenberg, a medic who had lost count of how many wounds he had patched up during the day, fell wearily into a shell hole behind the bluffs of 'Bloody Omaha'. He reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a sheet of V -mail and a pencil. 'Somewhere in France') he started his note. 'Dear Mom and Dad, I know that by now you've heard of the invasion. Well , I'm all right.' He put his pencil up. There had been too mu ch- he could think of nothing more to say.

Framed by the barrel ora wrecked enemy tank, men of the 1St

Combat Engineers repair a road near Langendroich, Germany. Note lack of markings on jeep. (US Army)

19

Into France 'Despite the confusion that still existed in many of the smaller isolated units' , wrote General Bradley, 'our situation had materially improved by the morning of June 7.'

The I st Division pushed ahead, while sending troops back to mop up isolated pockets of German resistance. The 2/ 16th Infantry moved against Germans still in Colleville, its Company G going through the town by I am. A single group of fiftytwo Germans from the 726th gave up without any fight at all - they were talked into surrendering by a patrol from Company L wh ich had been captured the day before at Cabourg. Other Germans were not quite as eager to give up and many units on mopping up operations ran into stifflittle fire fights . General Bradley came ashore to the division's command post during the height of these oper-

The face of war: an ignored enemy corpse, spilled cartridges, wrecked buildings, and tired soldiers. A brief rest for Company G, 2nd Bn., ,6th Infantry, in the streets of Vellweiss, Germany. Note markings on half-track towing AT gun. (US Army)

20

ations. 'These goddamn Boche just won't stop fighting', General Huebner complained to him. ' I t'll take time and ammunition', General Bradley replied. 'Perhaps more than we reckon of both.'

A movement east towards Port-en-Bessin by the 3/ 16th and Company B, 745th Tank Battalion was not meeting much resistance. Huppain , on the coastal highway, was occupied by the evening of the 7th. The 1/ 18th crossed the Bayeux-Isgny highway just after noon, ambushing some German 352nd Division reconnaissance units. By evening the battalion took the high ground dominating the approaches to the Aure River near Engranville. The 3/26th moved steadily ahead: by 12. 15pm they were through Surrain; they crossed the Bayeux highway by 5pm, and by midnight they were dug in south-east of Mandeville. The 2/18th, with a platoon from Company C, 745th Tank Battalion, reached Mosles by 5pm, losing only a few men and one tank in the process. By nightfall on 7 June the division's objectives, except in the FormignyTrevieres area, had been reached. Infantry with tanks from Company B, 745th, cleared out the

--------

Formigny area by early morning on the 8th. On the 8th action moved to the division's left

flank at Tour-en-Bessin. The 26th Infantry, a company from the 745th and another from the 635th Tank Destroyer Battalion spent the day stalled by defences a long the Aure River. By that evening only one company of the 1st Battalion had managed to cross the river. Pressing on, the regiment went through the town by midnight, putting the enemy north of Tour-en-Bessin in danger of being cut off. Inside this enemy pocket were the I /726th and elements of the 5 17th Battalion, 30th Mobile Brigade. Resistance from these units was rugged. Company L, 3/26th, dug in north of Ste. Anne, was overrun by a sudden German attack . The Germans appeared equally surprised; many of them were riding bicycles and lorries, apparently not knowing the Americans were where they were. Vaucelles, a mile east ofSte. Anne, was retaken from the British at about the same time. With this wider door open, the Germans were able to withdraw their troops from the pocket.

The country the 1st Division now found themselves in was the bocage, a gen tly rolling terrain of small fields broken by dense hedgerows and thickets. It was magnificent country for defence. The hedgerows might have been made to hide machine gun nests, while the defenders could withdraw slowly, field by field, making the attack-

DUK Ws of the division's amphibious truck company await the order to cross the Roer river,-February '945. (US Army)

ers pay dearly for every kilometre. 'Across the neck of the Normandy peninsula, the hedgerows formed a natural line of defence more formidable than any even Rommel could have contrived', wrote General Bradley. 'For centuries the broad, rich flatlands had been divided and subdivided into tiny pastures whose earthen walls had grown into ramparts. Often the height and thickness ofa tank, these hedgerows were crowned wi th a thorny growth of trees and brambles. Their roots had bound the packed earth as steel mesh reinforces concrete. Many were backed up by deep drainage ditches and these the enemy utilized as a built-in system of communications trenches.'

It was through this country that the 1st had to press the attack. Luckily for Allied troops, German reinforcement was badly hampered by constant air attack and the fall of certain vital roads a nd towns. By 9 June the enemy on the division's front were identified as a replacement battalion of the 9 15th R egiment, a reserve battalion of the 9 16th and the reconnaissance battalion of the 352nd Division. There were also elements of the 51 7th Mobile Battalion. Most of the best German troops in the area were in prisoner-of-war cages.

21

By 13 June the division was twenty miles inland at Caumont, an old Norman town on a hill which rises some 750 feet above sea level and commands the upper Drome Valley. Unfortunately, whi le the division was where it was supposed to be, neither the US 2nd Division on its right flank , nor the British on its left, could keep up with the Big Red One's advance. The British made a serious attempt to straighten out the lines, but were stopped by tanks and fell back.

Around the pocket now filled by the I st Division were elements of the German 5th Parachute Regiment from the 3rd Parachute Division, the 340th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, and the 38th Panzer Engineer Battalion from the 2nd Panzer Division. All were first class, combat-hardened troops. On 2 I June the 38th Panzer Engineers were relieved by the 2nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 2nd Panzer Division. The.Big Red One dug in. German artillery rained on the town, and morc grey-clad grenadiers were brought into the area as reserves; but rather than risk a fu ll frontal attack on the division's position , the German used propaganda in the form of leaflets fired by their arti llery. Some said that the Americans did not have proper medical care for their wounded; some, #hich were much more interesting, were pornographic. The American artillery also fired leaflets, which were said to work rather well among nonGerman troops. The awaited attack never came. The 1st was relieved on 14July by the 5th Infantry Division and sent to join the break-out from the Cherbourg Peninsula after an all-too-short rest stay at Colombieres. The division was assigned to VII Corps which had cleared the town of Cherbourg, turned, and was now ready to push east. The general plan called for a break-ou t through Coutances with the 9th, 4th, and 30th Infantry Division in the lead and the I st in reserve. The USAAF and RAF would lead the attack by saturating German positions with bombs and rockets from 1,500 heavy bombers, 396 medium bombers and 350 fighter bombers.

' I watched the air bombardment that preceded the breakthrough from an upstairs window of the farmhouse [1st] Divarty was using then', wrote

Driving a bow-wave ofl iquid mud before it, a half-track APC of th e 16th Infantry ploughs along a flooded road in the Hiirtgen Forest, February 1945. (US Army)

A .30 ca l. machine gun team photographed near the Raer river in February 1945. The No. 2'5 slung MI Garand is clearly visible. (US Army)

correspondent A. J. Liebling. 'There were three ridges, the first two topped with poplars, the third with pines, between the farmhouse and the target area. One stream of bombers came in to the left of the farmhouse, turned behind the third ridge, dropped its bombs, and came away to my right; another stream came in over my right, turned, and went off to the left. For two hours the air was filled with the hum of the motors, and the concussions of the bombs, even though they were falling five miles away, kept my shirtsleeves fluttering.'

The 9th Division was to attack immediately after the bombing, opening a hole for the I st to follow through. Before the last aircraft had turned for its British airbase, however, a message came through to I st Division headquarters . In a disastrous blunder, the air strike had fallen on the Allied front li ne; both forward battalions of the 9th had been badly hit and were virtually destroyed. Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, observing the attack, had been killed in his foxhole. The 30th Division, also in place for the impending attack, had suffered as well; it lost as many men that day as it did on any other day of fighting.

Timing on this operation was vital- the attack must go on. The 1st rushed by the battered 9th, meeting only light German resistance. Some

23

Privatc Stockov, Co. D, 1St Bn. , 16th Infantry loads a capturcd Cerman mortar. (US Army)

bombs, by good fortune, had fallen on German positions, and there the enemy were stunned, their resistance shattered. By early on 27 July the little town of Marigny had been taken, while Combat Command A of 3rd Armored Division pushed by Marigny and reached the high ground north of Coutances. The next day the 16th Infantry, slipping by an enemy pocket overlooking Marigny, fought its way towards Coutances. Enemy resistance was tough; the defenders had tanks and '88s' . The division was taking more casualties than it had since 6June, but it pushed on, street-fighting its way into Coutances from the east, while the 4th Armored Division fought its way in from the north. It was house-to-house, street-to-street fighting until the two columns finally met. Then Patton's 3rd Army took off, racing southward to cut off the Brittany Peninsula. The 1st Division and the 3rd Armored Division swept along to cover Patton's left flank.

The two divisions ran into resistance along the Sienne River, near Gavray. On 31 July, as the 1st moved under cover of the darkness to cross the river,

a formation of Luftwaffe J u88s began dropping bombs on the crossing sites. Hardly a unit failed to get its share of bombs, mostly anti -personnel types. Even the divisional headquarters was hit, with General Huebner's aide being wounded and an air support officer killed. The attack was pressed, and by noon on I August the 2/ 18th and a task force from the 3rd Armored had taken the town ofBrecey and the high ground around it. The next target would be Mortain, a small city in Manche which overlooks a pass in the range of hills running from Avranches to Domfront. The division slowly pushed forward through heavy enemy small arms and arti llery fire during the day, and Luftwaffe bombing at night. Orders were then received to leave Mortain to the 30th Division and to turn towards Mayenne, on the western bank of the Mayenne River which flows generally north and south. The town was thought to be lightly held and movement towards it could be accomplished quickly over good roads.

'Advanced units shot out their reconnaissance and the power followed closely behind', says the division's history, Danger Forward. 'Supply was working nicely. Gasoline was on hand. Rations were ample. Action was not severe. Casualties were a lmost nil. Sweat was taking the place of blood , and the undamaged countryside in its late summer greenness was little indicative of warfare.

' In these moves the individual found himself existing under bewildering conditions of physical comfort and discomfort as the case might be. One night he would find himself housed in an enormous chateau, the next in a foxhole under the stars. One day he would be in a severe fight. Perhaps the same day he would also roll through a peaceful French vi llage at twenty-five miles per hour gazing into the smiling and cheering faces of the jubilant and friendly populace. An occasional bottle of wine generously given him by a Frenchman would help wash the dust from his parched throat and not infrequentl y, an apple tossed to him as he sped by would connect uncomfortably with his head. ButJoe was happy; his morale was high and the world was a pleasant place to be.'

The division sped through a string of quickly seen towns, back towards Normandy and the town ofla Ferte-Mace, near Argentan. The British 21st Army Group was pushing east tOwards Falaise and

Chambois. On 19 August British and American troops came together and captured more than 70,000 Germans in the Falaise pocket. The bulk of the German 7th Army, however, managed to escape.

The division then headed south of Paris, turning north-east towards the Belgian border and reaching the Mons area on 2 September 1944. On the way it captured thousands of leaderless Germans, mostly in small , broken units. France was free.

Into Germany The 1St Division found itself on'l I September 1944 on the banks of the Meuse, with the 30th Division on its left. By that evening the 30th had established a bridgehead across the river. The 1St was ordered to assault the famous 'West Wall', Germany's concrete and steel border defence line. The attack began at 8am on 12 September, against resistance as stubborn as any seen by the men of the Big Red One. By nightfall the 1/ 16th had broken through the first parts of the wall , capturing a number of pillboxes. This was, h()wever, the only real success among the division 's battalions, wh ich were mostly bogged down. The first complete breakthrough of the line was made on the afternoon of the 13th by the 3rd Armored Division, on the right of the 1St Division, around the heavily fortified city of Aachen. As the first city on the soi l of the Fatherland to come under attack, it was important for enemy morale that it be defended to the utmost, whatever the effort cost. The original German commander recommended evacuating the city, an idea rejected by Hitler, and one wh ich cost the commander his position. The garrison, made up of elements of the 246th Panzer Division * and the 34th Fortress Machinegun Battalion, was ordered to stand and die where it was.

The original American decision was to bypass Aachen, driving directly north-east. On 15 September the 16th Infantry cut the roads leading south-east out of Aachen and moved north-cast. VI Corps then ordered the whole division to aid the

"This designation is quoted from US Army in telligence sources o r the period in the Division's official history. \Ve can locate no mention ofs lIc h a unit in German works on the Panzer Divisions, but it may have been an ad hoc unit assembled briefly from scattered clements. Ed.

November 1944- men of the division's 26th Infantry slog through the frozen mud of a fores t track. (US Army)

3rd Armored in taking Stolberg and Munsterbusch , directly east of and behind Aachen. This would cut the city off entirely from the rest of Germany.

'On 17 September two battalions of the German 12th Infantry Division 's 27th Regiment, which had been hastily pulled off the Russian front, reequipped and sent to the area on ly a short time before, attacked the 1/ 16th and 2/ 16th. The attack was beaten off by II am and the 16th resumed its drive on Munsterbusch. Munsterbusch was defended by Battle Groups Bockoff and Schemm, made up of elements of the 9th Panzer Division. The Panzer soldiers had laid their defences skilfully , contesting each house and turn in the road. Despite this, the 1/ 16th reached its objective in M unsterbusch by late afternoon of 2 I September.

A Sherman tank of one of the division's armoured battalionsconverted into a 'tank retriever', according to the original caption- crashes a road-block of wagons in Kelz, Germany, early in March 1945. On the original print heavy applique turret armour can be seen beneath the scrim and foliage camouflage. (US Army)

The Americans drew the ring tighter around the beseiged city. The Germans, for their part, attempted to relieve it. A German attack developed on the morning of 24 September, which was beaten off by the 3/ 18th. Another, led by elements of the 27th Division, hit the 2/ 16th and 3/ 16th . It was supported by a massive artillery barrage during which more than 3,500 rounds were fired into the division area. Again , the Germans were beaten off. Yet again, on 9 October, another vain attack was launched by the Germans in a vain attempt to keep the division from consolidating its position on the high ground overlooking Verlautenheide. By 10 October Company Lofthe 3/ 18th took Haaren and completed the chain around Aachen. The first city in the Thousand Year Reich to be surrounded by Allied troops now awaited its fate. An ultimatum was delivered to the city's commander: surrender, or have the city pounded into rubble. It was rejected, although on Aachen's outskirts 1st Division skirmishers noted white sheets hung out as flags of surrender on many houses. The ultimatum's rejection came not in words, but in the form of an attack on the 18th Infantry, easily beaten off. The Germans tried to relieve the city with a thrust by the 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment aimed at two companies of the 16th and

26

18th Infantries on 12 October. The attack was a fierce one, led by eight tanks. By just after noon a part of the 16th had been overrun, but American small arms and artillery fire were taking their toll and by 3pm the Germans called their attack off. In front of one company position alone the bodies of 250 Germans were found.

While this kind of attack was being launched from outside the pocket, the 26th Infantry was fighting its way into Aachen in the worst kind of house-to-house fighting. By the morning of 13 October the 2/26th and 3/26th had managed to link up in the city. Late on 16 October a patrol of the 30th Division met men from the 18th Infantry. German attacks continued, with a major attempt by tanks and self-propelled guns being made on 19 October; at Ravelsberg the 18th Infantry fought it off ..

Because of the size of the area under attack the 1st had to be reinforced and the 2/ lloth Infantry, from the 28th Division, was assigned to the division for this operation. The troops were to secure the ground taken by the 26th Infantry. The advance was slow and costly, but as inexorable as a grinding mill-wheel. German defences were being eliminated one by one, and the enemy were apparen tly unable to force their way through from the outside to relieve the city.

At 7.3oam on 21 October the advance reached the city centre and at 12.05pm Colonel Wilck, commanding Aachen's defenders, wearily surrendered. In this fight the 1st Division took 5,637 prisoners. 'Germany is washed up', the colonel told his captors. 'The "V" weapons upon which the German propaganda leans so heavily can be no more than harassing weapons with no effect on the final outcome. Only America can save us, as 1 don't believe in miracles any longer.'

The struggle for Aachen was successfu l, but it meant very little in strategic terms. The Rhine was sti ll many miles away. It was, at best, only a symbol: a symbol which had cost the Allies dearly in terms of men and supply.

Supply was now becoming the major problem. In early October American Army Group G-4, in charge of resupply, reported only twO days ' stores of petrol on hand. Ammunition was also in short supply. The problem was that Antwerp was still in German hands and there was no deep-water port in

Europe that the Allies could use. Bad weather limited the amount of equipment which could be unloaded onto the Normandy beachesthemselves an unpleasantly long distance from the actual front. The high command had to decide whether to halt and build up its forces for a spring offensive, or to keep going with what it had in November, hoping it could scrape by with what was on hand. They settled on the second alternative, taking account of the enemy's vital need for a respite to build up his own forces. While Montgomery would push north the American 12th Army Group would go for the Rhine, with the 9th Army aiming towards Dusseldorf and th e I st Army, including the I st Division, towards Cologne. A corps would hold a thin line across the Ardennes, while south of them Patton 's 3rd Army wou ld tear through the Saar and cross the Rhine above Mannheim.

The jump-off date, which was only met by an enormous logistical effort, was to be 16 ovember, given good weather. The weatherman came through and, after a solid week of rain , a mighty air bombardment hit a long the whole front. After Aachen the I st Division moved to the Hurtgen Forest south of the city, where it was to make its attack. Eyewitness Ivan Peterman called the forest 'cold, gloomy and treacherous'.

'U nlike Longfellow's murmuring pines and hemlocks', Peterrflan wrote, 'the Hiirtgen is not primeval. It was hand planted in modern times by the order of the German General Staff, and in that methodical process there was plenty of malice aforethought. Every natural advantage is screened; the thick spruce and balsams squat, limbs to the ground, like football linemen challenging advance.

'Seven American infantry divisions and one armoured combat team tried to break the H urtgen. All emerged, mauled , reduced and low in spirits . Only two got all the way through: the 1St Infantry along the northern edge, and the 78th Infantry, which eventually seized the dams as the Roer campaign closed. Statistics reveal that for every yard gained, the Hlirtgen claimed more lives than any other objective the Americans took in Europe.'

The division's assignment was 10 cross the Raer River nonh of Dliren , move on and secure Gressenich and th e Hamrich- Tothberg ridge. At

12.45pm, following a bombardment which began a t 11.I5am, the 16th In fantry led the way from Schevenhutte towards Hamich, while the 26th In fantry sta rted moving through the Gressenich Woods. The 47th Infantry, which had been attached to the Big Red One from the 9th Division, moved out directly for Gressenich. The going was slow; the Germans had excellent artillery observation pOSLS and cannon and mortar fire rained down on the Americans. Tanks and lorries bogged down in the sloppy mud. It was not until the next day that the 16th took Hamich, and that success triggered heavy enemy counter-attacks, complete with tanks and self-propelled arti llery. The attacks were beaten off, but not without the use of every weapon against enemy armour- air support, artillery and hand-held weapons. One private even put a German tank out of action with a lucky bazooka shot through its hatch from a first-Roor window. By the evening of the 17th much of Hamich was firmly in American hands and the 1/47th was on the outskirts ofGressenich fighting it out house -to-house. Counter-attacks and slow US progress continued on the 18th. Beating back more counter-attacks on the 19th, the division went back onto the oflensive on the 20th. The 18th Infantry,

A 1St Division radioman and rifleman photographed near Kclz. Note that the lalter wears metal-snapped rubber overboots, and wears the divisional shoulder patch 011 his MI941 held jackc!. (US Arm~)

, March '945, Gladbach, Germany: a Sherman tank of the 745th Tank Bn. attached to 'Big Red One' . This a ppears to be a late -model M4A2 with 76m m gun mounted in the T23 turret. (US Army)

reinforced by a pla toon of 155mm self-propell ed howitzers, took Wenau on the 20th, and the entire town of Hamich fin ally fell .

Casualties were heavy, and the division put a ll sorts of troops from the already thin rear echelon into the front lin e, from military poli cemen to veterinarians. Every small town , every bend in th e road became an enemy stronghold. The 16th ran into th e German 47 th Volksgrenadier Division holding the castle of Schloss Laufenberg and, after another fi erce fight, LOok th e castle. Schon thaI was overrun by the division on 24 November, and the Germa ns sent the 8g th Infantry in to ta ke back both Schon thaI and th e castle. The a ttack was bea ten off but men of the Big R ed One noticed tha t the Germans refused to quit. Next cam e attacks by 3. Fallschirmjager Division, which also fa iled ; and by the 25 th the Langerwehe-Jungersdorfposition was in US hands. Men of Compa ni es E and F, 2/26th Infantry were not so lucky when they took Merode from the German para troopers. The Germans counter-attacked and cut off communica tions between the compa nies and ba ttalion. After two

28

days' fighting both companies, their ammunition exhausted, surrendered on 30 November.

German resistance to the division's advance was as tough as any the forma tion had encountered in Europe; casualties were fa r too high, yet the division pushed on towards the Roer, la unching a surprise a ttack- on Luchem on 4 December. The Germans were caught unawares in th e absence of prepa ra tory Allied a rtillery fire , and Divarty fire kept reinforcements from reachi ng th e town . Luchem fell easily, and there was no serious enemy counter-attack. German high command was prepa ring a blow of which the Americans had no hint as yet. Despi te this las t success, the November offensive, designed to break through the West Wall , fai led. The 1st was pulled out of th e line for rest, reorga ni zation and re-quipment near Henri Chappelle, Belgium, south-west of Aachen, on 9 December. The 16th In fa ntry were quartered in Monscha u.

Weilerswist, 5 March '945= Shermans of the 745th T ank Bn. move lip to support infa ntry of 2nd Bn ., ,.8th Infantry. The nearest appears to be an M4A3 with the T23 turret mounting a 76mm gun ; in the background, a cast-hull M4A I with a 75mm gun in the M34A I mount. Note lack orany markings on these tanks. (US Army)

The Ardennes As the infantrymen who had been slogging through the Hiirtgen Forest could tell anyone who asked, the Germans were certainly not read y to qui t yet, despite the optimistic Press reports being filed in Paris and London. On 12 October the German high command issued orders for Operation 'Watch on the Rhine', a counter-attack wh ich would capture Antwerp and drive the British off the continent.